Abstract

Global health inequities have created an urgency for health professions education to transition towards responsive and contextually relevant curricula. Such transformation and renewal processes hold significant implications for those educators responsible for implementing the curriculum. Currently little is known about how health professions educators across disciplines understand a responsive curriculum and how this understanding might influence their practice. We looked at curricula that aim to deliver future health care professionals who are not only clinically competent but also critically conscious of the contexts in which they serve and the health care systems within which they practice. We conducted a qualitative study across six institutions in South Africa, using focus group discussions and in-depth individual interviews to explore (i) how do health professions educators understand the principles that underpin their health professions education curriculum; and (ii) how do these understandings of health professions educators shape their teaching practices? The transcripts were analysed thematically following multiple iterations of critical engagement to identify patterns of meaning across the entire dataset. The results reflected a range of understandings related to knowing, doing, and being and becoming; and a range of teaching practices that are explicit, intentionally designed, take learning to the community, embrace a holistic approach, encourage safe dialogic encounters, and foster reflective practice through a complex manner of interacting. This study contributes to the literature on health professions education as a force for social justice. It highlights the implications of transformative curriculum renewal and offers insights on how health professions educators embrace notions of social responsiveness and health equity to engage with these underlying principles within their teaching.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over more than a decade, calls for health professions graduates to be more than ‘just’ clinically competent have increased in intensity (e.g. Frenk et al., 2010; Ng et al., 2019; Westerhaus et al., 2015). Graduates are called to be critically conscious (Frenk et al., 2010). In response, there have been initiatives among curriculum developers across the world to explore options for renewing their health sciences curricula. Some renewal processes have drawn on social sciences and humanities (Kuper et al., 2017; Ng et al., 2019) to work towards encompassing the ‘social roles of care’(Ng et al., 2022, p. 323) and pedagogies to challenge power and privilege (Sharma et al., 2018), highlighting attributes such as communication skills, leadership and professionalism. Others have called for ‘biosocial’ curricula (Westerhaus et al., 2015) and a focus on key values such as social accountability (Ross, 2015), encouraging the identification of social needs (Boelen & Woollard, 2011), as well as social justice and global health equity (Kumagai & Lypson, 2009). The intent in these initiatives is curricula that are designed to be socially responsive and contextually relevant in order to develop graduates who are, in Freirean terms, critically conscious of the society in which they serve (Jacobs et al., 2020; Ng et al., 2015).

These curriculum renewal processes hold significant implications for those educators who are responsible for implementing them. In health professions education (HPE), this cadre of educators ranges from clinicians to biomedical scientists who may or may not have been involved in the renewal processes, and the conversations about the underpinning principles. How the educator understands these principles, and how this understanding transfers into their teaching practice therefore becomes an issue requiring the attention of schools of health sciences, specifically key curriculum role-players such as programme leads, module and course coordinators, and those responsible for faculty development at the relevant institution, amongst others. This paper seeks to address this call.

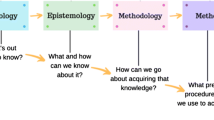

Theoretical perspectives

Critical consciousness as described by Freire (2000) is the ability to recognise oppressive social forces influencing society, and to take action against these injustices. For the purposes of this paper, critical consciousness refers to a state where health professionals (including those in training) question the causes of health inequity and intervene in health care contexts and systems with a view to transforming them into more socially just spaces (Jacobs et al., 2020). Transitioning from the current dominance of a biomedical curriculum model towards a more contextually relevant and socially responsive curriculum involves shifts at an epistemological and ontological level for both students and their educators (Jacobs et al., 2020). This speaks to transformative education through the adoption of a critical pedagogy (Freire, 2000), which requires critical reflection and awareness of social inequalities and power relations through a curriculum that enables students to be and become agents of change (Hudson et al., 2022; Ng et al., 2019). Freire’s work has been described as seeking to ‘upend traditional hierarchies’ where a critical pedagogy can ‘enable medical learners to perceive and address the social sources of illness that shape their patients’ lives’ (Cavanagh et al., 2019, p. 38–39). Different authors have argued for incorporating such a critical pedagogy in the context of HPE (e.g. Kumagai & Lypson 2009; Ng et al., 2019, 2022), with Ross (2015, p. 169) suggesting that ‘it provides an established framework which can be used to guide those interested in making medical education a force for social justice’. Given that this is our intent, we drew on the principles of critical pedagogy to inform our work, acknowledging that the education of health professionals towards the provision of equitable, responsive, and contextually relevant health care takes place within educational institutions and health care systems, located in complex social contexts that are fraught with inequities.

Concepts such as social justice, critical consciousness, social responsiveness and critical pedagogies are not easy concepts to work with and can engender fierce debate, often leading people to avoid confronting them or discussing the implications they might hold. Responses to calls for curricula that will foster graduates who are more socially responsive and critically conscious, what we have called ‘responsive curricula’, will therefore need to be mindful of how these complexities influence what is taught and how it is taught, both in the classroom and clinical learning spaces.

While acknowledging the necessity for transformational pedagogies, Cavanagh and colleagues (2019, p.41), suggested that ‘Freire’s pedagogy remains beyond the boundaries of medical education as it is imagined today’. In South Africa, however, the need for responsive curricula has been foregrounded, given the imperative to address barriers to health equity, that are characteristic of the past socio-political injustices (Mayosi & Benatar, 2014). This has prompted institutions responsible for the training of health sciences students in the country, including those who participated in the study that has informed this paper, to revisit and review their curricula. Earlier work conducted in South Africa suggests that health professions (HP) educatorsFootnote 1 involved in curriculum renewal initiatives acknowledged the need for transformation and critical reflection (Hudson et al., 2022; Jacobs et al., 2020), yet it remains unclear how HP educators across disciplines and institutions in South Africa understand the principles underpinning a responsive curriculum and how this understanding might shape their teaching practices.

Globally, the literature also appears to be relatively silent on the implications of such transformative curriculum renewal for the HP educator. The role that the HP educator, who will need to take responsibility for teaching and assessing within such a renewed space, is often assumed. However, if we accept that HP educators are indeed key to enabling the transformation that is being called for, then exploring how their understandings of the principles that underpin a responsive curriculum could shape their pedagogy, specifically their teaching practice, becomes critical. Therefore, when looking at the curricula in South Africa that aim to deliver future health care professionals who are not only clinically competent but also critically conscious of the contexts in which they serve and the health care systems within which they practice; our study was informed by two questions: (i) how do HP educators understand the principles that underpin HPE curricula and (ii) how do these understandings of HP educators shape their teaching practices? It seeks to align with the call to transform HPE by contributing towards the literature for equity and social justice. Our purpose is to inform ongoing curriculum development and delivery within this complex context with a view to strengthening transformative education through the adoption of critical pedagogies.

Methodology

This qualitative study was situated within an interpretive paradigm which acknowledges that there are multiple perspectives and that the researchers’ experiences and background shapes how we conduct, make sense of and interpret the research (Creswell & Poth, 2016). Six South African institutions were purposefully selected on the basis that they offer health sciences programmes; are situated in different regions; represent a mix of both urban and rural campuses; and a mix of both historically advantaged and disadvantaged institutionsFootnote 2. At majority of the institutions the researchers engaged with educators in two undergraduate health science programmes (only one programme from institution three was included), therefore the data includes insights from a range of undergraduate programmes (see Table 1). The study comprised three phases: phase 1 was a single site study at institution 1 (Jacobs et al., 2020); phase 2 involved the remaining five collaborating institutions which replicated the first phase of the study; and phase 3 comprised the synthesis of findings from phases 1 and 2. After receiving ethics review board approvals, a research team representative of each institution invited undergraduate programme coordinators, course module leads and others who teach in HPE to participate, in order to purposively recruit HP educators who were able to provide insights into a range of different courses which span the duration of the specific undergraduate programme, and therefore provide rich data with regard to the research questions.

Participants were invited by emails which outlined the intention of the study. All those who accepted the invitation were included, representing a variety of professions (medicine, occupational therapy, pharmacy, medical imaging, physiotherapy and clinical associates), teaching in a variety of learning contexts (e.g., university, hospital and community-based health structures). Participants all provided informed consent.

Focus group (FG) discussions and individual interviews were conducted over a three-and-a-half-year period (2019–2022). For phase 1, data collection took place face to face, while phase 2 data collection took place online (MS Teams) due to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. Each FG discussion comprised HP educators from the same programme and was informed by curriculum documents relevant to their respective programme, while the in-depth interviews further explored issues raised during the FG discussions. Participants were asked to reflect on their understandings of curricula that equip graduates to be both clinically competent and critically conscious, as well how their understandings shaped their teaching practices. On average both the FG discussions and the individual interviews were one hour long.

With the permission of the participants, all FG discussions and individual interviews were audio recorded. These were transcribed before coding commenced. Thematic analysis was done using an inductive approach (Braun & Clarke, 2021). The analysis process included the following: familiarisation with the data, a process of open coding, by a team from institution 1 (CJ, JB, MV, SvS and AH), took place during phase 1 and these codes were refined and revised in phase 2 and 3 with inputs from at least two representatives from each collaborating institution based on their coding of their own institutional data. Once all data had been coded, a smaller team (this authorship team) collaboratively conducted a comprehensive synthesis across all the data, searching for patterns of meaning, first focusing on the similarities, differences and range of perspectives offered by participants in terms of their understandings and teaching practices, and then exploring aspects of the interplay among these understandings and teaching practices. These patterns of meaning were arranged into themes. All data (71 transcripts) were analysed by institutional project team members using Atlas.ti (version 22.1.5.0, ATLAS.ti, 2022). Samples of the different institutional analyses were reviewed by a smaller team from institution 1.

Given the extent of the study, it was important to maintain consistency across the institutions involved in the study and ensure the trustworthiness of the data and the analytical process. CJ was included in the majority of the FG discussions and individual interviews and provided guidance to all teams during data collection, which facilitated continuity. The authorship team comprised a range of professional expertise including educationalists (CJ, SvS) and various health professions including audiology (AH), family medicine (JB; RC); homeopathy (KL); nursing (MV); occupational therapy (LHA), physiotherapy (NN), and radiography (PEH). All in the team are active in HPE research, with several having extensive experience as qualitative researchers. The project team met 16 times across the study period, over and above multiple sub-group meetings within the different institutions, where we critically reviewed and discussed our analyses, mindful of how our assumptions and expectations could influence the interpretation of the data (Braun & Clarke, 2019).

Institution 1 who was responsible for the coordination of the research project received ethical approval from the university institutional review board (Reference number: TL-2018-8838) after which the remaining collaborating institutions received ethical approval and site permission from their respective ethics committees and departments.

Findings

The data was characterised by a rich variability, with responses speaking to a wide range of understandings and practices. In this section we adopt a layered approach in presenting our findings, first exploring the range of understandings and practices in some detail, and then considering the interplay between them. Quotations are identified by institution number and transcript number (e.g. 1:4 refers to institution 1: transcript 4).

Range of understandings

The participants understood the notion of a responsive curriculum and the principles underpinning such curricula in different ways. Drawing on the work of Barnett (2009) we clustered the range of understandings expressed under the following themes: knowing; doing; being and becoming.

Knowing

There was a sense among the participants that the principles underpinning responsive curricula were something that could be presented or taught as a content area – thus something that could be ‘known’. Some participants understood this body of knowledge in narrow instrumentalist ways, as content (in this instance the social determinants of health) that could be taught in a lecture:

‘Well, most simplistically, we teach exactly this, the social determinants of health. It’s a specific lecture … focussed around social determinants from work environment to nutrition to economic status, to everything that we think is social determinants in health … so it’s practical and a knowledge base …’ (1:4)

Other participants, however, understood the underpinning body of knowledge in broader terms as something premised on theoretical perspectives that needed to be engaged with:

‘So, it is, I think, a … theoretical way of thinking that incorporates this sort of critical consciousness that we’re talking about.’ (5:54).

These participants were more critical of the narrower technicist understanding of taught content:

‘…looking at transformation purely as a content issue, what it is that we’re teaching students … then we can tick that box and we can say, right we’ve done it we’ve transformed our curriculum…we can on the periphery change the content but that doesn’t change anything … a transformation project with respect to the curriculum, has to come in at the nexus between the learner and the teacher and the content. To address the content is only to address one aspect of that…’ (5:47).

Doing

A responsive curriculum was also described as something practical that could be developed as a set of skills or behaviours – that would manifest in what students did. Again, we identified a range of understandings with some participants narrowly describing a set of skills underpinning the various roles that healthcare practitioners needed to play:

‘I have always felt that, let’s call it the softer skills. I know some people don’t like the word, but the softer skills, the collaborator and communicator, and what have you. That should be part of the practical blocks. It shouldn’t be part of the theory blocks’ (1:6).

Others understood it as competencies:

‘So, I think yes, aspects of like empathy, or empathic behaviour, or empathic treatment or engagement with patients, social awareness, yes, I think within that umbrella if you like, of professionalism and attitudes towards and engaging with patients, it probably could be considered a competency, yes’ (2:32).

However, there were participants who expressed a broader understanding of the practical implementation of social responsiveness, expressing it as taking action to bring about change for the betterment of society:

‘If you look at South Africa, there are lots of social injustices. There are inequalities across the health system, and so part of creating graduates that are more socially responsive, it’s also about trying to change those systems, so that we address those inequalities and hopefully, in time to come, that there can be more sort of equal opportunities and much better health for all … someone who understands how the social political and economic factors affect healthcare, and that they are able to harness that understanding to take action … to do something about the social political and economic factors that are impacting on healthcare’ (6:59).

Being and becoming

In this third cluster, participants understood a responsive curriculum as one that would foster a way of being and becoming that emanates from a process of introspection which continuously develops deeper criticality of self in relation to the world. For some participants being was about an awareness of the broader contexts within which ill-health occurs:

‘…above and beyond being contextually relevant, understanding your position within that context and being able to differentiate between your context and the context of others that you will come into contact with, and just that awareness and ability to kind of critically reflect on yourself in relation to others, you know, that the context is different for different people’ (5:48).

Becoming was seen as a developmental process, with many participants referring to it as a journey:

‘I feel it’s a journey that they need to be in, but that we get to a point, maybe at their five- or ten-years post-graduation, they are also able to look back and see that they have come through … where they are becoming critically consciousness, or aware of the things, like the inequities or the social constructs, or the diversity of the environment’ (2:34).

There were also participants who understood a responsive curriculum as involving not only self-reflection and awareness-raising for students, but also for HP educators:

‘…as a teacher, I have to understand that I’m bringing certain assumptions and ways of thinking about the world into the classroom and the way that I talk about the content with students is going to be informed by where I come from, my history and my geography and my culture, my language…’ (5:47).

Finally, there were participants who felt that responsiveness was more than “being” as simply about awareness of self and context, to include “becoming” as requiring critical reflexivity:

‘…students becoming aware and identifying some of their own assumptions, and questioning the meaning of those assumptions, and then through analysis and reflection and reflexivity, try to start to acknowledge what needs to change, and what alternative behaviours they could develop’ (5:49).

Range of teaching practices

The different ways in which the participants understood the principles that underpin a responsive curriculum, found expression in a range of teaching practices. It should be noted, however, that in some instances responses referred to actual teaching practices while in others participants were reflecting on teaching practices that they aspired to implement to bring about the shifts in thinking that they desired. Key themes related to the need for practices to: be explicit, be designed according to certain enabling principles, facilitate learning in the community, embrace a holistic approach, encourage safe dialogic encounters, and foster reflective practice.

Being explicit

A key focus was the importance of teaching practices that are explicitly described and explained in order to facilitate the implementation of a responsive curriculum.

‘I think there are different ways. One is by making it explicit, the other is by example. It’s not to say that they will always recognise the example. Therefore, you have to make the example explicit’ (2:8).

This included being intentional and deliberate when choosing teaching and learning activities, when role modeling, as well as drawing on educational principles or theory to guide practice:

‘What is really, really helpful is that we use Paulo Freire’s guide to levels of consciousness, which is very explicit in terms of the types of activities that one can use …’ (5:49)

Participants felt that HP educators should be explicit about the purpose and intent of what they were doing such as when planning opportunities for exposure to the health system within context.

Designed according to certain enabling principles

Designing teaching practices in a manner that allows for integrated, structured and aligned teaching, creating opportunities for weaving issues related to social responsiveness and contextual relevance as a golden thread throughout the teaching practices, was also noted:

‘through primary healthcare, palliative care and extending the time in the clinical platform, I think we are bringing students closer to patients, and allowing them more time to understand the patient in their context’ (6:65).

While this was reflected as a current teaching practice in some instances, other participants felt that the idea of integration could be taken further. Participants emphasized the importance of scaffolding the learning and positioning the learning encounters relative to what has gone before and what is coming next, for example connecting the theory to the practical, and the classroom to the workplace/clinical based learning. Pedagogic practices should embrace an inter-professional ethos:

‘starting at first year, I think the sooner you get that kind of interdisciplinary kind of work, in terms of mixing healthcare professionals, identifying a project in the community in which they live, and it can be very low key to start in first year, that actually worked well, because I think it opened the students up to other healthcare professionals and we weren’t working in silos, …’ (3:36).

However, there were challenges in terms of what was prioritized in the pedagogic engagement. Logistics and administration often made it difficult to design teaching practices as integrated, appropriately aligned and scaffolded across the various years of teaching, the different teaching platforms (classroom and clinical) and across the different teaching teams:

‘There is a lot of pressure in terms of getting through everything … The pressure on the clinical platform, and also the pressure in the classroom to get through everything, that makes it difficult to really, I think, open some of those boxes.’ (1:21).

Learning in the community

Most participants highlighted the importance of where the learning and teaching takes place. Facilitating learning in the community was reported as a significant teaching principle. Experiential learning that brought students closer to the reality of patient’s lives, such as community engaged learning and learning within hospitals especially in primary health care facilities, were considered valuable approaches:

‘We make sure the students are in the hospitals early on, and are conscious of the community they serve, because they come from those communities, and I think it’s a good thing… In that way, making sure that, you know, being socially conscious of what’s going on in their environment, was evident’(2:24).

Immersion in the patient’s world was seen to provide an authentic learning experience that complemented so-called theoretical lectures. This immersion facilitated awareness of context with some participants suggesting that longitudinal and sustained learning in the community was optimal.

Embrace a holistic approach

Participants indicated that teaching practices should embrace a more holistic approach, creating opportunities to facilitate student learning that extends beyond biomedical content, including, for example, a biopsychosocial approach. As noted earlier however, this practice was positioned as aspirational with many suggesting that current practices are still predominately bio-medically focused:

‘So, the reason why we tell them hang up your stethoscopes is because if they take their stethoscopes, they will be so focussed on making a diagnosis and treating, and we’re trying to get them to see that before the patient gets a disease, there are certain things happening in their life, social determinants are playing out, things are happening at the home, in the community’ (2:25).

Encourage safe dialogic encounters

Participants felt that a dialogic approach to learning was needed where educators encouraged and enabled conversation and debates, making space for the presence of student voices. This was seen as a catalyst for creating awareness and critical thinking:

‘So, how do we enable students? How do we create the space and the place and the confidence perhaps to be able to start talking about these issues, because I think students would love to engage on these levels. But you know, we just need to facilitate that dialogue in some way’ (5:56).

They indicated that teaching practices needed to create spaces to allow for difficult conversations that could disrupt assumptions, norms, and biases, and question issues of power that perpetuate health inequities. Participants reflected that to create a safe space and foster openness in students, educators may need to be vulnerable themselves:

“…. some of it is developing that trust with each other, that trust between the student and the academic coach, and getting to a place of being vulnerable, and .. facilitating the conversation in such a way where they feel safe…” (2:24)

Some, however, reported that this was challenging and they experienced uncertainty about not knowing how to facilitate such encounters.

Foster reflective practice

Finally, participants indicated that teaching approaches should create opportunities for reflective practice and critical thinking. They highlighted how these approaches have the potential to enable opportunities for students to experience the sort of ‘disorientating dilemmas’ which enabled transformative learning and growth for the student, as well as the educator:

‘So X has raised the issue of transformative learning. I think I see this very much around Mezirow and transformative learning process and changing the context, giving students disorientating dilemmas, essentially to change, and helping them to reflect and grow on that’. (1:8).

Participants also highlighted the uncertainty they experienced in their pedagogical approaches, reflecting that it required the student and the educator to move out of their comfort zone, particularly in relation to assessing beyond the biomedical:

‘I don’t know if you can call it a soft skill, but… how do we assess it… We don’t know how to say ‘yes, you are a critically responsive student’ (6:58)

Thinking about understandings and practices

Our initial premise for exploring the understandings of HP educators with regards to the principles that underpin curricula that aim to be responsive was that the understandings educators have will influence their pedagogies and practices. As can be seen from the analysis, different perspectives arose from the range of understandings and teaching practices represented across the data. As we continued iteratively engaging with our data, we explored two issues emerging from these differences in greater depth: (i) whether HP educators should strive towards a common set of understandings or simply share and acknowledge their different understandings; and (ii) whether delivering a responsive curriculum was the responsibility of all HP educators or just some.

In terms of whether HP educators should strive towards a common set of understandings, some participants supported the need ‘to have a shared understanding amongst us as lecturers so that when we send the students out there, we need to know that they’ve met this criterion or they are competent’ (3:40). These participants considered that there might be a right way of being responsive and that a standard set of understandings could be developed to enable a common ground. However, others motivated for the acceptance of a range of understandings, such as ‘self-examination, self-awareness, understanding my own biases, prejudices and how it might impact on the way I interact with others’ (1:1). One participant expressed a view that this is ‘a different way of thinking’ (6:62) thus a cognitive understanding, while another felt that the goal was to empower students ‘to talk against injustices’ (2:26), suggesting a far more agentic understanding.

To achieve the sharing and acknowledgement of different understandings, one participant argued for a ‘coalition of the willing’: ‘We have just never come together as a collective. It’s like a coalition of, like the willing, if you like, to take it forward together. And I know they are there. They are there. I have come across them’ (2:27). Among the participants there were also those who embraced the variety of understandings as these allowed for students’ individuality, as they too entered with a range of understandings.

Drawing these ranging perspectives closer was the notion that opportunities for dialogue would be helpful in creating a bridge between HP educators’ understandings and their teaching practices.

‘… we could benefit from a platform where we sit and actually discuss these issues, cause … my interpretation is different to what the other person’s interpretation is, what we are gonna put out there is also gonna be quite confusing to the students as well. So, I think we need to start to do our own homework or just amongst ourselves first and look at what it is … and how do we relate these concepts into our teaching? And how do we instil it in our students? (3:36).

In this view, which affirms the interconnectedness between understanding and practice, there is a responsibility on the educator to be self-aware and for the team of HP educators to inform the curriculum and their concomitant teaching practices through a process of engagement. Such engagement would move towards a comprehensive representation, capturing the range of understandings and teaching practices in a meaningful way, but not enforcing a single perspective or approach.

Although the initial analysis showed that HP educators across the various institutions and programmes understood the need to deliver a ‘responsive curriculum’, there were differing views as to whom the responsibility belonged and how to engage educators in the process. Questions about responsibility played out on a practical level, where, for example, moving beyond the ‘traditional classroom’ was often linked to additional planning, logistics and administration. On a more macro or programme level, ensuring the sort of integration, longitudinality and inter-professionality, identified as necessary principles for teaching practices that would foster critically conscious graduates, was seen as a significant endeavour and participants felt there was less clarity about where the responsibility lay.

Some participants proposed the understanding that it was the responsibility of all HP educators to deliver a responsive curriculum:

‘… we as a faculty, or as a team, need to decide what values, what framework, and I think maybe we need to revisit our graduate outcomes and our objectives and our whole, and become passionate about the type of teaching we are wanting to do…’ (6:58).

They acknowledged, however, that it would not be easy to get everyone on board, but that it would be important to create awareness and develop a shared understanding of the underpinning principles to get everyone’s buy-in:

‘I think as lecturers, it’s crucial… to have an understanding of what our responsibility is…, but I am wondering, are the lecturers actually aware of the social issues out there, and do they understand... ’ (5:47)

Regarding the notions of ‘shared responsibility’ and ‘buy-in’, participants called for a more systematic approach:

‘So, I think it’s going to require a fair amount of buy-in, and it takes time for people to buy in. Not everyone is orientated … it’s happening in pockets, but it’s not happening systematically, and that is where the challenge is. It needs to happen systematically’ (6:64).

Developing graduates who are both clinically competent and critically conscious takes place in a complex system involving multiple interdependent parts, including the HP educators, their students, various parties with an interest and elements in both the education and the health systems in which the teaching and learning happens. Differing perspectives arise when the participants within that system recognise that components of that system are not in alignment, or that there is uncertainty on how the collectives of HP educators, the students and the system elements can align amongst themselves and between each other for the optimal outcomes.

‘… one of the strategies is you need to include more people, the right people ... if universities or faculties are responsible for servicing the greater community, surely between faculty and the local environment, core issues could be identified, and then those become the project of the faculty. So all the disciplines have to meet….’ (1:14)

Several participants felt that delivering a responsive curriculum was not the responsibility of everyone. Some felt that they were not trained to do it, others felt that they do not know how to teach such important competencies, and some clinicians felt that they were not educators:

‘… as educators… we haven’t actually been trained. We don’t have that background to actually say, OK, these are the things that we need to do so that we can get our students to this point of being critically conscious. ‘Cause we’re just (discipline named) that have now come from the clinical environment and are teachers… that’s one of the biggest challenges. You have all these ideas and these notions that are critical for students to have, but nobody has enabled the educators to have these skills first and you know teach them to be able to teach this concept’ (3:36).

This analysis demonstrates the complex interplay between understandings and practices, and points to a need for shared platforms and opportunities for dialogue among all stakeholders, as well as a more systematic approach to ensure that all elements of the system are in alignment.

Discussion

In this study we have provided an in-depth exploration of the understandings that HP educators, representing a range of health professions across several institutions, hold with regards to the notion of responsive curricula and the sort of teaching practices they believe would foster learning towards the development of critically conscious graduates. We have drawn on the work of Paolo Freire’s critical pedagogy and have intentionally adopted a social justice agenda. Work in HPE around critical consciousness has grown in recent years, but typically the focus has been on medical education (Manca et al., 2020). This study extends existing work in that it is multi-institutional and across a range of health professions.

As suggested earlier, an initial premise for this research was that as HP curricula embrace notions of social responsiveness and health equity, HP educators are faced with the challenge of giving voice to these principles in their teaching. The way in which they do so is, however, shaped by how they themselves understand what it means to be socially responsive and what health equity represents for them. The differing perspectives of the participants, as well as the many factors that influenced their understandings and pedagogies, speak to a complex array of variables. The relationship between understandings and practice is not linear or straightforward and each of the variables carry fundamental implications for teaching, including clinical teaching, and learning of future healthcare professionals.

We have exposed a melting pot of understandings, that point to critical consciousness as something that can be known, something that can be enacted, and something more internal that leads to a process of being and becoming (Barnett, 2009; Barnett et al., 2001). Teaching towards critical consciousness, irrespective of the educator’s understanding, may require the implementation of teaching practices not traditionally seen in HPE, and the creation of learning opportunities that embrace a less familiar body of knowledge. This suggests that HP educators may themselves need to expand their way of knowing – and revisit what they believe counts as knowledge (Jacobs & van Schalkwyk, 2022) – adopting a different ‘way of being’ in the world. It further suggests that the system within which responsive curricula are implemented, needs to expand its way of knowing to enable and support HP educators to grow into this area.

The range of understandings emphasise the importance of self-awareness and critical reflexivity, the role of relationships, and an awareness of context. We would argue that the process towards critical consciousness, for both the educator and the students, is developmental, without an obvious endpoint speaking to notions of lifelong learning and commitment. It does, however, have a starting point – the self. The process of reflection and self-introspection is about understanding one’s own worldview and positionality, and the values informing it. It requires a willingness to change (Halman et al., 2017), challenging biases and stereotypes (Carter et al., 2020) as well as the assumptions underpinning our work as educators (Frambach & Martimianakis, 2017), and acknowledging new ways of knowing (Paton et al., 2020). We acknowledge that this may be a discomforting and disruptive process (Frambach & Martimianakis, 2017). The process of HP educators working with self, with one’s own premises and worldviews, needs to precede engaging with students around these issues so recognising what both parties bring to the educational space. Hence, knowing, doing, being and becoming is facilitated through critical reflection, dialogic encounters, and learning from the community. Ng et al., (2019, p. 1122) argue that implementing social sciences and humanities in HPE is not easy work and requires ‘thoughtful’ application.

Apart from acknowledging the role of ‘self’, critical introspection was also seen as requiring a collective endeavour – the ‘coalition of the willing’ mentioned earlier. Building on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framework which posits that understanding human development requires a focus on the entire ecological system that surrounds the individual, Ajjawi and colleagues (2017) call for a more nuanced understanding that sees a network of social interactions. We find this position useful, envisaging an ongoing cycle of knowing, doing, being and becoming, characterised by an emerging awareness of the self, extending over time across the network of relationships with no obvious endpoint. An important caveat, of course, is that within the system not all influences are enabling. Our study clearly demonstrates how context influences knowing and doing in both enabling and constraining ways.

Additionally, in the South African context we can see that understanding issues of inequity, power and privilege in the context of social responsiveness and critical consciousness is a necessary but not sufficient condition. We argue that this is also applicable to other contexts globally. It is equally about recognising that the educational environment is “not neutral” (Manca et al., 2020, p. 958), and how these issues play out in contexts beyond the university, through interactions with educator colleagues, patients and carers who are located in communities, which in turn are located within broader society. This highlights the importance of the relationship, the nexus between HP educator, student, HPE colleagues, patients (and carers), communities and society at large. If developing critical consciousness is indeed a spiralling, emergent process that students journey through, there might be value in articulating an aspirational common goal for a responsive curriculum. There might also be different but reciprocal goals for the HP educator and the student. For the HP educators, challenging the dominant culture within HPE and striving for responsive curricula will require courage, having difficult conversations in ‘brave’ rather than ‘safe’ spaces (Araon et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2021) with students and with colleagues in their departments and faculties, and then considering the implications for curricula, teaching and student learning. We are therefore arguing that a network of relationships, emanating from a process of self-introspection, can become the space in which social responsiveness and critical consciousness might be taken up in HPE.

Which brings us back to pedagogy, the critical pedagogy that fosters the awakening of critical consciousness among our students and that is interwoven with the broader goal of social justice and social change. Our respondents described a wide range of pedagogical approaches and teaching practices, some of which they had implemented, others clearly aspirational. These resonate with the principles of transformative learning theory as they have been taken up in HPE literature, particularly since the publication of the Lancet Commissioned report on health professionals for a new century (Frenk et al., 2010). A recent scoping review on transformative learning, highlighted ‘immersion in a different context, specifically outside of the classroom’, engaging with communities, group work, encouraging reflective practice, and providing ‘opportunities for dialogue and the use of narrative’ (van Schalkwyk et al., 2019, p. 551). Kumagai and Naidu describe ‘safety, intentionality, and awareness of transition’ as the ‘essential qualities of the educational space’ (Kumagai & Naidu, 2015, p. 287). Halman et al’s (2017, p. 18) list of ‘common practices of a critical pedagogy’ also demonstrate much similarity with those we have exposed.

In summary, we are arguing for an awareness that leads to the sort of conscientisation that Freire (2000) called for, and for a critical engagement around the range of understandings that individual HP educators have regarding the notion of a responsive curriculum and the related theoretical underpinnings, within the collective network. Such collectives would need to be collaborative in nature, foster cohesive debate, placing an emphasis on the ‘dialectic pedagogy’ that was central to Freire’s work (2000). Bleakley (2020) argues a collective approach in HPE is valuable, we concur and emphasise the need for collective conversations to take place across the ecological network importantly at institutional level (Elkins, 2003; Nielsen, 2016) and, in the context of this research, also at disciplinary level. We are encouraged that for some this process has already begun and we underscore the importance of small shifts towards such critical engagement which may hold significant potential to be a catalyst for meaningful transformative change.

There are limitations to this study. We intentionally wanted a large group with diverse institutional contexts and a variety of programmes. This does mean that interrogation of individual environments could be compromised and further work that will explore issues more deeply at institutional level and within programmes, is envisaged.

The work has also highlighted avenues for future research. Transitioning from understandings to examples of actual curriculum renewal and the resultant changing practice will allow us to appreciate the value of this study to stimulate shifts towards more responsive curricula. Thus, implications for curriculum renewal processes at a more granular level need to be further explored. This then proposes developing guidelines within a flexible, non-prescriptive framework that may shift us towards identifying foundational content, considering core opportunities for real world experience, and identifying appropriate teaching activities.

Concluding thoughts

We support the argument offered by Halman and colleagues (2017) that adopting a critical pedagogical approach has transformative potential to shift the outcomes of HPE towards graduating “an authentically and critically attuned carer who fundamentally embodies core human values of social justice with a commitment to continually improve upon the status quo’ (Halman et al., 2017, p. 19). In this article, we argue that to drive transformation towards socially responsive and contextually relevant curricula in HPE requires a collective endeavour across a network which includes the HP educators, the students, the communities, and the patients. Furthermore, the understanding and teaching practices that HP educators bring are of fundamental importance to this transformation of the curriculum. Therefore, HP educators need to undergo a process of self-introspection towards becoming critically conscious of the contexts and systems that continue to perpetuate health inequalities.

Notes

In this paper the term “HP educators” refers to all who teach on HPE programmes including those teaching in the classroom and those teaching in the clinical areas (Jacobs et al., 2020).

Under the Apartheid government institutions were structured according to racial groups. Historically disadvantaged institutions were established through the Extension of the South African University Education Act (No. 45 of 1959), which sought to separate institutions of higher learning for the country’s white and ‘non-white’ communities. The historically disadvantaged institutions were largely located in rural or remote communities, had less resources (human and financial) allocated to them and had poorer developed educational facilities and infrastructure in comparison to the advantaged (white) institutions (Department of Higher Education and Training, 2013).

References

ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH [ATLAS.ti 22 Windows]. (2022). Retrieved from https://atlasti.com

Araon, B., Clemens, K., Arao, B., & Clemens, K. (2013). From safe spaces to brave spaces: a new way to frame dialogue around diversity and social justice. In L. Landerman (Ed.), The art of effective facilitation: reflections from Social Justice Educators (pp. 135–150). Stylus Publications.

Barnett, R. (2009). Knowing and becoming in the higher education curriculum. Studies in Higher Education, 34(4), 429–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070902771978.

Barnett, R., Parry, G., & Coate, K. (2001). Conceptualising Curriculum Change. Teaching in Higher Education, 6(4), 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510120078009.

Bleakley, A. (2020). Embracing the collective through medical education. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 25(5), 1177–1189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-10005-y.

Boelen, C., & Woollard, R. (2011). Social accountability: the extra leap to excellence for educational institutions. Medical Teacher, 33(8), 614–619. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.590248.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360.

Carter, K. R., Crewe, S., Joyner, M. C., McClain, A., Sheperis, C. J., & Townsell, S. (2020). Educating health professions educators to address the “isms. NAM Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.31478/202008e.

Cavanagh, A., Vanstone, M., & Ritz, S. (2019). Problems of problem-based learning: towards transformative critical pedagogy in medical education. Perspectives on Medical Education, 8(1), 38–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0489-7.

Creswell, J., & Poth, C. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Department of Higher Education and Training (2013). Report of the ministerial Committee for the review of the funding of universities. https://www.dhet.gov.za/Financial and Physical Planning/Report of the Ministerial Committee for the Review of the Funding of Universities.pdf

Elkins, S. L. (2003). Transformational learning in Leadership and Management positions. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 14(3), 351–358.

Frambach, J. M., & Martimianakis, M. A. (2017). The discomfort of an educator’s critical conscience: the case of problem-based learning and other global industries in medical education. Perspectives on Medical Education, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-016-0325-x

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th Anniv). New York: Continuum.

Frenk, J., Chen, L., Bhutta, Z. A., Cohen, J., Crisp, N., Evans, T., Fineberg, H., Garcia, P., Ke, Y., Kelley, P., Kistnasamy, B., Meleis, A., Naylor, D., Pablos-Mendez, A., Reddy, S., Scrimshaw, S., Sepulveda, J., Serwadda, D., & Zurayk, H. (2010). Health professionals for a new century: Ttransforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. In the Lancet. Elsevier B V, 376(9756), 1923–1958. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5.

Halman, M., Baker, L., & Ng, S. (2017). Using critical consciousness to inform health professions education a literature review. Perspectives in Medical Education, 6, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-016-0324-y.

Hudson, L., Engel-Hills, P., Davidson, F., & Naidoo, K. (2022). Radiography lecturers’ understanding of a socially responsive curriculum. Radiography, 28(3), 684–689.

Jacobs, C., & van Schalkwyk, S. (2022). What knowledge matters in health professions education ? Teaching in Higher Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2022.2111207.

Jacobs, C., Van Schalkwyk, S., Blitz, J., & Volschenk, M. (2020). Advancing a social justice agenda in health professions education. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning, 8(2), 112–131. https://doi.org/10.14426/cristal.v8i2.272.

Kumagai, A. K., & Lypson, M. L. (2009). Beyond cultural competence: Critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. In Academic Medicine (Vol. 84, Issue 6, pp. 782–787). https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a42398

Kumagai, A. K., & Naidu, T. (2015). Reflection, dialogue, and the possibilities of space. Academic Medicine (90 vol., pp. 283–288). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. 3https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000582.

Kuper, A., Veinot, P., Leavitt, J., Levitt, S., Li, A., Goguen, J., Schreiber, M., Richardson, L., & Whitehead, C. R. (2017). Epistemology, culture, justice and power: non-bioscientific knowledge for medical training. Medical Education, 51(2), 158–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13115.

Manca, A., Gormley, G. J., Johnston, J. L., & Hart, N. D. (2020). Honoring Medicine’s Social Contract: a scoping review of critical consciousness in Medical Education. Academic Medicine, 95(6), 958–967. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003059.

Mayosi, B., & Benatar, S. (2014). Health and Health Care in South Africa-20 yeas after Mandela. The New England Journal of Medicine, 371(14), 1344–1353.

Miller, J. L., Bryant, K., & Park, C. (2021). Moving from “safe” to “brave” conversations: committing to Antiracism in Simulation. Simulation in Healthcare, 16(4), 231–232. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000605.

Ng, S. L., Crukley, J., Brydges, R., Boyd, V., Gavarkovs, A., Kangasjarvi, E., Wright, S., Kulasegaram, K., Friesen, F., & Woods, N. N. (2022). Toward ‘seeing’ critically: a bayesian analysis of the impacts of a critical pedagogy. Advances in Health Sciences Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-021-10087-2.

Ng, S. L., Kinsella, E. A., Friesen, F., & Hodges, B. (2015). Reclaiming a theoretical orientation to reflection in medical education research: a critical narrative review. Medical Education, 49(5), 461–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12680.

Ng, S. L., Wright, S. R., & Kuper, A. (2019). The divergence and convergence of critical reflection and critical reflexivity: implications for Health Professions Education. Academic Medicine, 94(8), 1122–1128. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002724.

Nielsen, K. L. (2016). Whose job is it to change? New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 147, 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl

Paton, M., Naidu, T., Wyatt, T. R., Oni, O., Lorello, G. R., Najeeb, U., Feilchenfeld, Z., Waterman, S. J., Whitehead, C. R., & Kuper, A. (2020). Dismantling the master’s house: new ways of knowing for equity and social justice in health professions education. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 25(5), 1107–1126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-10006-x.

Ross, B. M. (2015). Critical pedagogy as a means to achieving social accountability in medical education. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 6(2), 169–186.

Sharma, M., Pinto, A. D., & Kumagai, A. K. (2018). Teaching the Social Determinants of Health: a path to equity or a Road to nowhere? Academic Medicine, 93(1), 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001689.

Van Schalkwyk, S. C., Hafler, J., Brewer, T. F., Maley, M. A., Margolis, C., McNamee, L., Meyer, I., Peluso, M. J., Schmutz, A. M. S., Spak, J. M., & Davies, D. (2019). Transformative learning as pedagogy for the health professions: a scoping review. Medical Education (53 vol., pp. 547–558). Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 6https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13804.

Westerhaus, M., Finnegan, A., Haidar, M., Kleinman, A., Mukherjee, J., & Farmer, P. (2015). The necessity of Social Medicine in Medical Education. Academic Medicine, 90(5), 565–568. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000571.

Acknowledgements

This paper has emerged from work conducted as part of the Responsive Curriculum Project which is a South African based multi-institutional project led by the Centre for Health Professions Education at the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University in collaboration with the Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Sefako Makgathu University, the University of Cape Town, the University of the Western Cape and the University of the Witwatersrand. The authors wish to acknowledge all of the staff in these different institutions who participated in the study. The authors also thank all participants for taking part in the focus group discussions and interviews and for sharing their experiences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors helped shape the research, contributed to the analysis, reviewed and provided critical feedback on the manuscript. AH, CJ, PEH and SvS wrote the main manuscript text

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hansen, A., Engel-Hills, P., Jacobs, C. et al. Understandings and practices: Towards socially responsive curricula for the health professions. Adv in Health Sci Educ 28, 1131–1149 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-023-10207-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-023-10207-0