Abstract

Collaborative approaches such as Problem Based Learning (PBL) may provide the opportunity to bring together diverse students but their efficacy in practice and the complications that arise due to the mixed ethnicity needs further investigation. This study explores the key advantages and problems of heterogeneous PBL groups from the students’ and teachers’ opinions. Focus groups were conducted with a stratified sample of second year medical students and their PBL teachers. We found that students working in heterogeneous groupings interact with students with whom they don’t normally interact with, learn a lot more from each other because of their differences in language and academic preparedness and become better prepared for their future professions in multicultural societies. On the other hand we found students segregating in the tutorials along racial lines and that status factors disempowered students and subsequently their productivity. Among the challenges was also that academic and language diversity hindered student learning. In light of these the recommendations were that teachers need special diversity training to deal with heterogeneous groups and the tensions that arise. Attention should be given to create ‘the right mix’ for group learning in diverse student populations. The findings demonstrate that collaborative heterogeneous learning has two sides that need to be balanced. On the positive end we have the ‘ideology’ behind mixing diverse students and on the negative the ‘practice’ behind mixing students. More research is needed to explore these variations and their efficacy in more detail.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

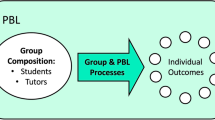

The advent of Problem Based Learning (PBL) curricula in medical schools globally continues to “generate passionate discussions” as the literature on its benefits and drawbacks continues to expand (Tavakol et al. 2009). The small group learning which meets all the conditions for collaborative learning (Dolmans and Schmidt 2006) is a central element in PBL (Dolmans et al. 2005). In addition to academic heterogeneity, due to globalization and affirmative action policies higher education institutions are now more linguistically and culturally heterogeneous. Hence student populations are now more demographically and functionally diverse consisting of students from different ethnic, cultural, language, age, social class, gender, secondary schooling and prior educational training backgrounds. In light of this, it is important to understand issues related to group composition and group dynamics in order to optimize the positive group learning outcomes and to address the challenges in theses diverse group learning environments. Thus the need highlighted by Slavin (1996) for more research focusing on collaborative learning in homogeneous and heterogeneous settings has increased relevance in current times.

Heterogeneity is defined as a composition of diverse parts i.e., the higher the diversity the higher the heterogenity. However, the term heterogeneity is often used interchangeably with the word diversity in the literature. In an attempt to catergorise different types of diversity Milliken and Martins (1996) in their review of management research found that a common distinction is made between diversity on observable or readily detectable attributes and diversity with respect to nonobservable or underlying attributes. Observable attributes refer to differences such as race or ethnic background, age and gender. Nonobservable attributes include differences in values, socioeconomic status, education, skills and knowledge. They further elaborated that these two types of diversity are not mutually exclusive e.g., ethnicity may be associated with socioeconomic status and that observable attributes evoke responses that are due directly to biases and prejudices. Due to its association with affirmative action and hiring quotas, the term diversity also seems to provoke intense emotional reactions (Milliken and Martins 1996).

Watson et al. (1993) in their study on undergraduates in a traditional type management course found that only over time did culturally diverse groups become as proficient in process and total task performance as the homogeneous groups. Wright and Lander (2003) concluded from their study that (p. 250) “there can be little assurance that arranging groups of mixed-ethnic membership will lead to profitable intercultural interaction.” In addition, collaborative relationships are often dependent on the participants’ “culturally-based definitions of the situation” (Mercer 1996). Cohen (1994) highlights that in-equities in participation based on gender, race, and ethnicity within cooperative groups should be a source of serious concern for those who recommend cooperative learning for heterogeneous settings and the effects of cooperation maybe far less desirable. Cultural dissimilarity in heterogeneous groups encourages deviation from the essential skills needed for cooperation (Dornyei 1997). Dornyei (1997) highlights that essential skills needed for high quality cooperation such as leadership, decision making, trust building, communication and conflict management need to be taught and developed. Hence simply placing students in a group and expecting them to be cooperative is ineffective especially in ethno-linguistic heterogeneous groups.

Also if group selection is out of the student’s control and consists of diverse membership then distinct skills are needed to manage themselves, their attitudes and their group effectively (Wright and Lander 2003). Hence collaborative learning approaches may provide the opportunity to bring together diverse students with mixed ethnicity or backgrounds but their efficacy in practice and the complications that arise due to the mixed ethnicity needs to be further examined (Wright and Lander 2003).

Cohen (1994) also found that results of cooperative learning at times differed according to the ethnic or racial composition of the group. Springer et al. (1999) in their meta-analysis of the studies on effects of small-group learning on undergraduates in science, mathematics, engineering, and technology could not find sufficient data to analyze whether the racial or ethnic composition of groups moderated the effects of small-group learning on students’ attitudes. They also highlighted that although cooperative learning research may have an enormous empirical base, there are still gaps in the literature particularly around the analysis of studies about undergraduates in actual classroom or programmatic settings. There is also a need to investigate in more depth the conditions and factors that contribute to students’ dissatisfaction in collaborative group work in diverse settings such as group cohesion (i.e. how well the students feel connected to the group) (Singaram et al. 2008, 2010). An in-depth understanding of the diverse dysfunctional groups would shed more light on understanding the issues that need to be addressed in these situations so that appropriate recommendations and strategies could be implemented. There is also a lack of literature that explores the impact of different types of diversity in group composition on the affective reactions of group members i.e., does observable attributes or underlying attributes such as educational background create more serious negative affective reactions (Milliken and Martins 1996)?

Using a qualitative approach, this study aims to explore in more depth the perceptions of students and teachers regarding multicultural learning contexts, diverse group dynamics and the underlying effects of diversity on collaborative heterogeneous PBL groups.

Grounded theory (Strauss 1987) will be used as a systematic qualitative research approach to generate theory based about heterogeneous group learning by making use of focus group interviews (Kitzinger 1995). In focus group interviews the group is considered the unit of analysis and relies not only on a question and answer format but also on the interactions that occur in the group. Hence this research strategy is inductive and provides fertile ground to extract and investigate underlying views, perceptions and opinions of the diverse heterogeneous students as they engage, in group learning within the formal and informal PBL curriculum settings. Also, focus group interviews as opposed to individual interviews will mimic the actual group learning setting where students can share their thoughts, opinions and ideas and interact with one another by debating and agreeing with each other which might then lead to generating new or extended thoughts and views on the issued explored.

Research question

What are the key advantages and disadvantages of heterogeneous (multi-cultural, multi-lingual and multi-knowledge levels) small group tutorials in problem-based learning?

What suggestions do students and teachers have on how to solve the key problems encountered (if any) and how to enhance the advantages of heterogeneous small group tutorials in problem-based learning?

Method

Context

In 2001, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine (NRMSM) implemented a 5-year PBL curriculum to replace the traditional 6-year medical curriculum. The PBL curriculum consists of horizontally and vertically integrated themes designed around cases or problems. The first 3 years of training consist of PBL themes and an introductory clinical methods course starting in third year. In each of the themes in the first 3 years, students meet bi-weekly in predetermined small groups of 10–12 students to discuss the relevant cases using an eight step method which is adapted from the University of Maastricht (Schmidt 1993). Students are exposed to the clinical world from first year with relevant health care contacts and clinical skills training which is primarily based in the skills laboratory. In the fourth and fifth year, students rotate in blocks through all the medical and clinical disciplines.

NRMSM characterises the South African rainbow nation in its highly diverse multilingual and multicultural student population. The population consists of students with at least thirteen different first languages which also include languages from other parts of Africa, minimum of five different race groups and a range of prior educational training experiences, ages, and schooling backgrounds. Prior educational training refers to other science/medical science undergraduate and postgraduate studies that students undertake prior to entrance into medical school. These students referred to as mature students and make up about a third of the undergraduate class. The other two-thirds are made up of matriculants.

The school backgrounds of the matriculants differ in terms resources, infrastructure and methodologies implemented in a variety of private, semi-private and public secondary schools which students need to complete prior to attending tertiary institutions. The difference in the school structures results in students having different levels of academic preparedness and skills when they enter medical school.

In light of heterogeneous student population, faculty at NRMSM engineer the PBL tutorial groups by mixing them in an attempt to distribute or balance the diversity of the students ‘equally’ across the groups. Hence, students are not randomly assigned to the tutorial groups but rather mixed based on their race and gender. The groupings are changed for every theme which is approximately every 6–9 weeks.

Subjects

A stratified random sample of twenty second year medical students towards the end of the second semester of study were selected taking into account the student backgrounds related to ethnicity, previous tertiary experience, language, gender and age. These students had almost two years experience working it diverse PBL tutorials and were accessible subjects for the study as third-fifth years have varying degrees of clinical rotations in a variety of hospitals outside the medical school. The student population was divided into homogeneous groups or strata based on these diversity factors. Students were randomly selected from each strata based on the proportion of that stratum in the student population of that year cohort to form a heterogeneous group sample. Hence a theoretical sampling strategy (i.e., individuals who would have a perspective on the topic were selected because they were involved in heterogeneous group learning and came from different backgrounds) was employed.

Students were individually approached to ascertain their comfort in discussing issues in heterogeneous as opposed to homogeneous groups. All the students indicated that they were comfortable. The absence of two students in each of the respective groups on the day of the interview did not upset the heterogeneous balance in the group. Their twenty PBL facilitators were also invited for a focus group interview. Eleven facilitators accepted the invitation based on their availability. The facilitators had a range of basic, medical, health, allied health, racial and language backgrounds. They all receive compulsory training prior to being allowed to facilitate. At the beginning of every new theme the facilitators are briefed by the subject experts/theme head on the details regarding the learning goals and objectives for each week. In total two student groups of ten students were involved and one group of 11 facilitators. Each group met twice.

Instrument

The focus groups were semi structured and the interview scheme was designed to explore the advantages, disadvantages and suggestions regarding being in/facilitating mixed heterogeneous (multicultural, multilingual, multi-educational) PBL groups?

The principal investigator conducted the focus group discussions for students and facilitator groups. A moderator who also acted as the scribe was also present. The focus groups were held for 90–120 min period. After an introduction and setting of some basic ground rules for the group to prevent potential limitations in focus groups such as dominating students, students were asked the questions and before answering they were requested to jot down key points regarding their responses. Discussions were audio taped. Students and facilitators input were recorded anonymously as they were given numbers prior to the discussion.

Summaries of the discussions were presented to the groups for authentication. The second round for the facilitators had to be cancelled due to unforeseen circumstances and could not be rescheduled. In the second round of student meetings specific issues that needed more clarifications were explored and students had a chance to comment further on the issues discussed. After the second round of discussions no new points emerged from the discussions, due to which the researcher and the moderator were of the opinion that saturation was achieved and a third round was not necessary. In total five focus group sessions were held. Refreshments were provided at each meeting and each student received a small stipend in appreciation for their time.

Analysis

The summaries of the data after the first round of interviews were analyzed and clarification points were noted. This was further explored in the second round of discussions. The complete data were then analyzed in depth.

The tape-recorded discussions were transcribed literally and uploaded into the ATLAS-ti software program. Using the basic idea of the grounded theory an inductive approach to the data was taken. The data was read and re-read to “discover” or label variables and their interrelationships by using open (identifying, naming, categorizing) and axial coding (relating codes or categories) (Strauss and Corbin 1998). The principal investigator (VS) read the transcripts and designed a set of preliminary codes. This was then discussed by the two researchers (VS and DD) and the transcripts were re-read. A trained assistant then read the transcripts and independently came up with a coding framework. The coding framework was then discussed by all researchers (VS, DD & CvdV) and modified until conformity and verification was reached. Transcripts were then re-read and coded using Atlas-ti. The coded data was then grouped into relevant categories and underlying relationships were explored. Hence the themes and categories were determined or emerged from the data as opposed to grouping the data into a set of preselected categories. Thematic analysis resulted in the identification of the nine main themes.

Results

Table 1 illustrates a summary of the main themes. Illustrative quotes were selected to support the emerging themes from the analysis of the focus group discussions as discussed below.

Opportunities

Mixed tutorial groups enhances students interaction across diverse boundaries

The collaborative group setting creates a sense of familiarity and togetherness that leads to intergroup relations in mixed groups. Students get to know each other better and bond irrespective of race, colour and creed as they focus on the tasks and learning goals using the PBL steps. The impact of this togetherness across the diversity results in students crossing barriers and interacting freely as outlined by this male Indian student regarding his interaction with black students.

..…when you get into your tutorial groups, you do your work, and….you get to know other people as well…. (and) you actually bond with them. Sometimes its like you walking on like campus maybe at the cafeteria you chat with them, and you think, oh, by the way, that person is black…… so you greet people you’d never think you’d greet… (G1-1:69)

Collaborative learning in diverse tutorial groups prepares students for their future profession in a multicultural society

The interaction and social cohesion in the PBL tutorials, encourages students to develop collegiality amongst their group members that may not blossom into friendships beyond being effective role players in teams. Being able to adjust and comply with team members in diverse resource constraint environments is an essential skill especially during their Internship and Community Service years. Recognising and appreciating the need for unity in diversity is also important, as students need to be able to define their roles and responsibilities’ as they integrate across cultures and ethnicity for the collective deliverance of effective health care in a multicultural public sector.

I don’t personally believe that we are here to make friendships. So I’m not here to be in a tutorial with number one and next week I’m going to be go playing touch rugby with them with a bunch of my friends… I think that we are being too ambitious. But one thing I feel is that we need to be able to make acquaintances so when I finally have to work in an internship with someone who’s not from my background, I should be able to relate with them…..(and)… freely interact with other people without prejudice. (GR1R1-1:88)

Collaborative heterogeneous group learning serves as an effective transformative academic development tool

Collaborating in PBL groups as opposed to being competitive creates a safe environment that helps bridge inequalities amongst students especially those who have different levels of academic preparedness. These differing levels are attributed to poor schooling and differing socio-economic backgrounds. The researching, sharing and activation of prior knowledge between peers creates fertile academic environments for these students to become enriched. Misconceptions are addressed and scaffolding of discipline specific and integrated knowledge is also encouraged specifically between matriculants and mature students (explained earlier). In addition, as students at higher levels of knowledge engage with the material in interactive discussions, students at lower levels become motivated to achieve higher.

when you get like mixed into these groups, and you get…different kinds of people of more…you know, I’d say more intelligent than others, some are more exposed, so let’s say like, you haven’t quite reached that… place, so you sort of get motivated when you see you know, how others are …….how much effort other people put into their work, and then…for the whole week you’ll be thinking, no… I want to know my work like that. (student -G1R1-1:)

English second language (ESL) students’ usually converse in their native language within and outside of the medical school environment. The collaboration in the small group tutorial ‘forces’ and creates a forum for second language students to engage socially and academically by contributing, engaging and discussing in formal and informal English dialogue. This enhances the student’s confidence and literacy skills that would impact positively on the success of the students.

…I have improved my communication skills and the way that I associate with people. (G2R1-2:12)

Challenges

Students within mixed tutorial groups segregate and do not fully integrate

Poor group dynamics is one of the contributing factors to dysfunctional groups. A lack of ground rules and team formation can contribute to students feeling uncomfortable with each other in the tutorials. This issue is expounded in multicultural diverse groups as it decreases tutorial group effectiveness and negatively impacts on the cognitive and social domains of the PBL tutorial as reflected by a student below.

.. there is just this isolation amongst students, even in tutorials. …… I don’t know what the problem is….and it is very difficult for you as an individual to go up to a group of ten people from a different culture and try to be friends with them or try to get information from them. It is very difficult. (G2R1- 2:45)

The second quote below from another student highlights how ethnic heterogeneity compounds these issues further. Because of different cultures and the lack of understanding of them, it is difficult to create a sense of ‘we’ or ‘us’ in the group. Students within the tutorial groups segregate because all students from the same culture stuck together, perhaps due to psychological divisions and past prejudices. Polarizing around the tutorial table along racial lines decreases group morale.

all the white people stuck together and all the Indians and all the blacks so basically it’s the same as me coming from a rural school where there’s only black people …. you’d expect that we would integrate but we don’t…. (G1R1- 1:81)

Mixed tutorial groups create unequal social status and unequal chances between groups of students

The diverse socioeconomic backgrounds create unequal social status in the group and leads towards unbalanced discussions, quiet students, withdrawing. Differences in social status impacts on student’s self-esteem making them feel inferior. This hinders participation and contribution in the group.

another thing is social status, I mean … those people, who are part of not such a fortunate environment, and there are people out there who are better well off………we have different things…..that comes through academically, because he feels he can’t be at that level, meaning that he’s not going to speak out in a tutorial, ….…..while the other person who has a better social standing, their mistakes are kind a brushed off and taken as if their shortcomings are not as big. (G1R1-1:38)

Diversity or mixed groups hinder student learning in the groups

Although weaker students can benefit in mixed groups, they also find it challenging to keep up with stronger students. This may be attributed to the language and academic constraints of these students. The compounding effects of being a student with a rural background from a government funded school does place these students at a disadvantage when they have to enter into discussions in tutorials with brighter students from privately funded schools.

if you are all not on the same level, you find that some people do get left behind. Whether its language or they don’t understand or maybe you are not perhaps from the same Matric school and some people live in the rural areas, there are going to be those people who are going to be left behind … (G2R1-2:31)

On the other hand having only certain students constantly give information and explanations upsets the balance in the group and results in these stronger students feeling frustrated.

but even though we were a bit frustrated, but we couldn’t do anything about it, but we did try to explain it as much as we could,…. and it is also like some students didn’t do the same subjects in Matric, like one student hadn’t done biology I think and then like basic things that we all, well most of us, majority. …90% of us had known, and they didn’t know and that was a little bit frustrating. (student—G1R1-1:33)

Facilitators also found that the learning of stronger students is hindered due to the lack of academic stimulation and motivation.

… one student I felt was streets ahead of the rest of his group and he was frustrated and it really didn’t go well. (FP7-7:50)

Recommendations

Teachers should encourage active participation of all students and pay extra attention to some students to create equal chances for all students in the groups

In mixed groups facilitators need to manage the group dynamics not just between students and their personalities but also across cultures, languages, race, social class and academic background. In general tutors play an important role in ensuring that the group is functioning effectively, e.g., by stimulating quiet students to speak up.

for us Africans, most of us Africans, we don’t just speak…….. So we need some sort of stimulation to start…. (G1R2-6:36)

Some facilitators are aware of this added role and are keen to address the inequalities of the past. Their acceptance of this responsibility is important for the social cohesion, motivation and equal participation in the group. However, it is no easy task.

..I mean we’ve been in the apartheid era for so long and the disadvantaged black students and Indian students often feel inferior to a white student who comes from a different educational background. In that sense, I feel that the facilitator’s role is to engage them and tell them that they are on a common ground and we don’t have any structural differences. We don’t worry about which background you come from, we are here to learn from each other and it is very difficult …. (FG09-7:4)

Teachers need training in how to deal with heterogeneous groups

In addition to facilitating diverse groups effectively, facilitators need to be made aware of students’ expectations in heterogeneous groups and be appropriately skilled to handle them. Creating an equitable environment across cultures is paramount to addressing power issues and inequalities prevalent in the diverse groups. Diversity training and conflict resolution is critical to subdue the pride and prejudice that creeps in, and its damaging effects on group effectiveness.

Below we have a student who expresses concern over how a rural was treated in the group and her expectation of the facilitator:

I’m really hurt to find that he felt that somebody referred to him as a ‘farm boy’ and he may not know anything, because I know those are obstacles you may find in your tut groups……..I think that it is very important that the facilitator should also play a role in setting the tone and the atmosphere, so that everyone is able to feel comfortable…I think that is the responsibility of the facilitator. (G2R1-2:21)

Another student highlights the gap and misconceptions due to racism that plague faculty and student relations and negatively impacts on the collaborative group dynamics.

We think the facilitator thinks that black students don’t have enough knowledge because he wasn’t including us …

Facilitators have become aware of their limitations compounded by their lack of knowledge and skills to facilitate students and groups with diverse backgrounds. There is now a desire to understand the diverse students holistically and the underlying factors that impact on their contribution in the group.

in terms of like the background that the students are coming from…. it would be important to know that or understand …. why the students are not responding and why they don’t interact as we would like them to do in the group. If I knew that about their background, if I had some kind of prior knowledge, it would have been helpful, it would have been beneficial.

(FG09-7:48)

The ‘right mix’ for group learning in diverse student populations

Facilitators recommend that the ‘right mix’ of diversity is needed in heterogeneous collaborative learning. Currently attempts are made to group students based on race and gender, but facilitators emphasize grouping should be based on academic strength i.e., appropriate portions of strong and weak students. This would enhance the cognitive aspects of collaborative learning that includes interactions and elaborations. By doing this the motivational aspects of the PBL tutorial such as social cohesion would also be enhanced.

It is helpful if the group has the right balance and there isn’t a great diversity where some brilliant students in the room and for everyone else is much lower down. If there is more a range then they have people to interact with and people to challenge them and to ask questions and so on (P7:fac-gr-7:59)

Currently facilitators are randomly placed. Facilitators expressed that getting the right mix also refers to choosing or selecting the appropriate facilitator for the appropriate groups. This could be based on expert knowledge and experience. This is a new concept that needs to be explored in more detail.

….another thing use the stronger facilitator where the group has students with less knowledge… (P 7: fac-grp-7:55)

Conclusion and discussion

The data from this study portray collaborative heterogeneous PBL group learning as a scale. In other words on the one hand, we have the “ideology” behind mixing diverse students (which certainly has some positive advantages) and on the other we have the “practice” behind mixing students (the negative side of mixing groups). This finding supports earlier studies that describe diversity as a double-edged sword (Milliken and Martins 1996) or a dark cloud with a silver lining (Watson et al. 1993). The recommendations are aimed at meeting the challenges and bridging the gap between ideology and practice. Hence trying to balance this scale presents as art that needs to be mastered and maintained.

The first balancing dilemma is where we find that diverse groupings encourage interaction but on the other hand there is still segregation. The inter-racial and cultural social interactions encouraged by heterogeneous cultural and ethnic grouping are in keeping with earlier studies (Singaram et al. 2008, 2010). Students having difficulty seeking information from individuals in different cultures and segregating within the group may be attributed to the ‘in-group’ factor which is characterised by members who share common interests and goals (Wright and Lander 2003). This finding highlights that faculty need to be cautious in diverse settings as students may not always be comfortable, willing and engaging in collaborative learning settings. It is evident here that an individual’s participation in any given interaction in collaborative learning is influenced and shaped to some degree by his or her cultural orientation and assumptions (Wright and Lander 2003). Hence a multi-cultural student population at a learning institution does not necessarily mean that there will be positive interactions in intercultural collaborative learning (Wright and Lander 2003) but collaborative learning in theses mixed groups also provides the opportunity to nurture positive interactions.

Working in mixed PBL tutorials across cultures helps prepare medical students for their future profession in a multicultural society, but we also found that status factors prevalent in inter-group relations hinders student participation in the small group tutorial. This dichotomy presents as the second dilemma. Students becoming more tolerant and patient with each other is an ‘altruistic’ benefit that is important, as preparing students to become effective team members in their future organizations is a critical outcome of most educational institutions (Sweeney et al. 2008) particularly in diverse populations as in South Africa. However, it is important to be aware that status factors as highlighted by Cohen (1994) affect interaction within small groups and hence their productivity. Hence this study highlights the importance of taking into account relational factors in mixed groups and its impact on participation. The issue of who contributes in the group and how it is managed is also highlighted.

The third dilemma we found is that on the one hand students can learn a lot from each other due to the academic heterogeneity and language literacy, but on the other these differences hinder student learning. The educational diversity of the students in our study consists of those who have been exposed to a wide variety and “range of standards of primary and secondary education” (Engelbrecht et al. 2008). The interactions in the group helped the weaker students and also helped improve the communication skills particularly of second and third English language speakers. This positive outcome is important in light of the fact that only 8.2% of the SA population spoke English according to Statistics SA (Engelbrecht et al. 2008). However, the language barriers and disparate educational levels result in students becoming despondent and reluctant to contribute in the tutorials leading to dysfunctinal tutorial groups as highlighted by other studies (Hendry et al. 2003; Gill et al. 2004). Hence the group productivity in these groups will not be optimal as the interactions and elaborations as well as the social cohesion in the group will be low as withdrawing and sponging behaviors will keep group morale down (Carlo et al. 2003; Dolmans et al. 1998 and Singaram et al. 2008). A low group cohesion may be associated with withdrawing students or free-riders who might benefit from the students who are still actively participating. One-sided contributions frustrate the active participants in the group who may then themselves decide to withdraw.

Three main recommendations also emerged in the study. Firstly we found that teachers need to be well aware of the tensions discussed above and secondly they need training on how to deal with these tensions. The importance of this finding is supported in the literature. Wright and Lander (2003) found that when faculty don’t have adequate skills to effectively implement and facilitate group work and where students themselves don’t willingly participate and in a context that is already potentially problematic, member ethnicity is very likely to compound existing issues. Working collaboratively is can be both socially and emotionally demanding hence particularly well-developed skills are required to work collaboratively and inter-culturally (Wright and Lander 2003). A PBL tutor either “thrills or kills tutorials” and “a conducive learning environment can overcome apparent cultural barriers …as there are firm evidence that nurture matters more than culture in the teaching–learning environment” (Gwee 2008). The third recommendation is to create diverse groups based on academic abilities of the student and expertise of the teacher. This suggestion will perhaps ease the tensions in the groups discussed earlier but needs further investigation.

In addition to developing and refining skills to ensure optimum student motivation in diverse collaborative learning, it is also important for the curriculum to reflect and facilitate these goals. Curriculum content such as the case studies in the PBL tutorials should include diversity issues that encourage constructive input from the diverse learners and highlights the strengths that these differences can bring to a learning environment. Developing learning opportunities that require students to explore the activity through the eyes of different cultural backgrounds would create an interest and desire for students to want to work with students from different cultures and hence “overcome the usual issues of self-selection into same-culture groups" (Sweeney et al. 2008). This would perhaps then ease cultural tension and empower the learners to value their differences and diversity and take ownership of the group processes that would enhance group productivity and efficacy.

A final note, South Africa has been described as one of the world’s major social laboratories and the higher education sector “has inherited the full complexity of the country’s apartheid and colonial legacy. Racism, sexism, class discrimination continue to manifest themselves in the core activities of teaching, learning and research. However, in addition to challenges there are opportunities for this sector to play a vital role in transformation as the country attempts to shed the apartheid baggage” (Higher Education in SA -Report). This has indeed become evident in the findings of this study, which highlights that amidst the challenges wonderful opportunities are prevalent in diverse higher education sectors as students engage in collaborative learning in a multicultural, multiethnic, multiracial and multilingual contexts. Hence the scale referred to earlier, appears to be tipped to the positive end as the challenges that emerged from this study can be addressed.

The findings of this study are applicable nationally and internationally, as medical schools globally have become diverse. All over the world more and more problem-based curricula are implemented in which students from diverse backgrounds collaborate which each other when learning in groups. The findings in this study shed more light on the collaborative learning issues that staff and students should be aware of in heterogeneous group learning settings. However more research is needed about the influence of cultural differences on how PBL is implemented and works in practice in other countries with different and mixed cultures (Jippes and Majoor 2008).

A limitation of this study was the sole use of focus groups as opposed to the inclusion of individual interviews as some individuals may not have declared their difficulty in expressing freely their opinions and views. The moderator in this study did note that, although the responses in the focus were genuine, the respondents did seem to be choosing their words carefully when expressing certain thoughts. A degree of diplomacy was noted in their utterances, probably due to the groups being mixed. Opinions about ‘the other’ were expressed while ‘the other’ was present. The moderator also noted that presence of two staff members (moderator and PI) may have been a constraint, although the students are accustomed to interacting with them on an informal basis in the small group settings.

Future studies should explore and include observational methods to correlate with self-reported behavior. The ‘right mix’ of diversity in mixed groups and adjustment duration (Cox et al. 1991) of heterogeneous groups needs further exploration as well as how to train PBL teachers to be effective in diverse PBL groups.

References

Carlo, M. D., Swadi, H., & Mpofu, D. (2003). Medical student perceptions of factors affecting productivity of problem-based learning tutorial groups: Does culture influence the outcome? Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 15(1), 59–64.

Cohen, E. G. (1994). Restructuring the classroom: Conditions for productive small groups. Review of Educational Research, 64(1), 1–35.

Cox, T. H., Lobel, S. A., & McLeod, P. L. (1991). Effects of ethnic group cultural differences on cooperative and competitive behavior on a group task. The Academy of Management Journal, 3(4), 827–847.

Dolmans, D. H. J. M., de Grave, W., Wolfhagen, I. H. A. P., & van der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2005). Problem-based learning: Future challenges for educational practice and research. Medical Education, 39, 732–741.

Dolmans, D. H. J. M., & Schmidt, H. G. (2006). What do we know about cognitive and motivational effects of small group tutorials in problem-based learning? Advances in Health Sciences Education, 11, 321–336.

Dolmans, D. H. J. M., Wolfhagen, H. A. P., & Van Der Vleuten, C. P. M. (1998). Motivational and cognitive processes influencing tutorial groups. Academic Medicine, 73, S2–S22.

Dornyei, Z. (1997). Psychological processes in cooperative learning: Group dynamics and motivation. The Modern Language Journal, 81(IV), 482–493.

Engelbrecht, C., Knosi, Z., Wentzel, D., & Govender, S. (2008). Nursing students’ use of language in communicating with isiZulu speaking clients in clinical settings in KwaZulu-Natal. South African Journal of African Language, 2, 145–155.

Gill, E., Tuck, A., Lee, D. W., & Beckert, L. (2004). Multicultural task group tutorial dynamics and participation in small groups: a student perspective in a multicultural settings. New Zealand Medical Journal, 117, U1140.

Gwee, M. C. (2008). Globalization of problem-based learning (PBL): Cross-cultural Implications. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 24(3), S14–S22.

Hendry, G. H., Ryan, G., & Harris, J. (2003). Group problems in problem-based learning. Medical Teacher, 25, 609–616.

Jippes, M., & Majoor, G. D. (2008). Influence of national culture on the adoption of integrated and problem-based curricula in Europe. Medical Education, 42, 279–285.

Kitzinger, J. (1995). Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal, 311, 299–302.

Mercer, N. (1996). The quality of talk in children’s collaborative activity in the classroom. Learning and Instruction, 6(4), 359–371.

Milliken, F. J., & Martins, L. L. (1996). Searching for common threads: Understanding the multiple effects of diversity in organizational groups. The Academy of Management, 21(2), 402–433.

Report of the Ministerial Committee on Transformation and Social Cohesion and the Elimination of Discrimination in Public Higher Education Institutions. 30 November 2008. FINAL REPORT. Retrieved February, 2010 from http://www.ukzn.ac.za.

Schmidt, H. G. (1993). Foundations of problem-based learning: Some explanatory notes. Medical Education, 27, 422–432.

Singaram, V. S., Dolmans, D. H., Lachman, N. & van der Vleuten C. P. (2008). Perceptions of problem-based learning (PBL) group effectiveness in a socially-culturally diverse medical student population. Education for Health, 21(2), 116.

Singaram, V. S., Van Der Vleuten, C. P. M., Van Berkel, H., & Dolmans, D. H. J. M. (2010). Reliability and validity of a tutorial group effectiveness instrument. Medical Teacher, 33(2), e133–e137(1).

Slavin, R. E. (1996). Research on cooperative learning and achievement: What we know, what we need to know. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 21, 43–69.

Springer, L., Stanne, M. E., & Donovan, S. S. (1999). Effects of small-group learning on undergraduates in science, mathematics, engineering, and technology: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 69(1), 21–31.

Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques and procedures for developing theory. USA: Sage.

Sweeney, A., Weaven, S., & Herington, C. (2008). Multicultural influences on group learning: A qualitative higher education study. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(2), 119–132.

Tavakol, M., Dennick, R., & Tavakol, S. (2009). A descriptive study of medical educator’s view of problem-based learning. Medical Education, 4(9), 66.

Watson, W. E., Kumar, K., & Michaelsen, L. K. (1993). Cultural diversity’s impact on interaction process and performance: Comparing homogeneous and diverse task groups. Academy of Management Journal, 36(3), 590.

Wright, S., & Lander, D. (2003). Collaborative group interactions of students from two ethnic backgrounds. Higher Education Research and Development, 22(3), 237–252.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the medical students and staff of NRMSM for their participation in this study and the National Research Foundation (NRF) in South Africa for funding. A special thank you to Prof TE Sommerville from NRMSM for being the moderator in focus group discussions and for contributing to the group observations.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Ethical Clearance

Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Singaram, V.S., van der Vleuten, C.P.M., Stevens, F. et al. “For most of us Africans, we don’t just speak”: a qualitative investigation into collaborative heterogeneous PBL group learning. Adv in Health Sci Educ 16, 297–310 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9262-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9262-3