Abstract

Introduction The development of professional behaviour is an important objective for students in Health Sciences, with reflective skills being a basic condition for this development. Literature describes a variety of methods giving students opportunities and encouragement for reflection. Although the literature states that learning and working together in peer meetings fosters reflection, these findings are based on experienced professionals. We do not know whether participation in peer meetings also makes a positive contribution to the learning experiences of undergraduate students in terms of reflection. Aim The aim of this study is to gain an understanding of the role of peer meetings in students’ learning experiences regarding reflection. Method A phenomenographic qualitative study was undertaken. Students’ learning experiences in peer meetings were analyzed by investigating the learning reports in students’ portfolios. Data were coded using open coding. Results The results indicate that peer meetings created an interactive learning environment in which students learned about themselves, their skills and their abilities as novice professionals. Students also mentioned conditions for a well-functioning group. Conclusion The findings indicate that peer meetings foster the development of reflection skills as part of professional behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of professional behaviour is one of the important objectives for students in Health Sciences. Professional behaviour can be defined as the integration of knowledge, skills and attitude (Arnold 2002; Korthagen 2004). In order to develop their professional behaviour, students need to develop skills that allow them to reflect on their own experiences and thus be able to shape their professional behaviour (Schön 1983, 1987; Thijs and van den Berg 2002; Ash and Clayton 2004; Korthagen 2004; Meijer 2005; Tigelaar et al. 2006). Reflection is therefore fundamental to the development of professional behaviour (Goldie et al. 2007).

The fostering of reflection usually aims to make students conscious of their behaviour, professional or otherwise (Rogers 2001; Ash and Clayton 2004; Meijer 2005; Driessen et al. 2005; Goldie et al. 2007; Mansvelder-Longayroux et al. 2007). Students analyze their professional experiences and try to understand and clarify their professional behaviour. This kind of reflective action may lead to adaptation or even change in professional behaviour.

A variety of methods and reflection programmes that encourage and provide students with opportunities to reflect as part of their professional behaviour have been described. For example, portfolio-based learning has been mentioned as a tool to encourage student reflection (Pearson and Heywood 2004; Mansvelder-Longayroux et al. 2007). Others have suggested that working with other professionals is important for enhancing the quality of reflection (Tigelaar et al. 2006). An improvement in reflection skills was also found when descriptions of professional situations (vignettes) were used as a tool to encourage reflection (Boenink 2006).

Several other studies (Gokhale 1995; Thijs and van den Berg 2002; Meijer 2005; Tigelaar et al. 2006) claim that working in a group entails collaboration, which results in improved reflective skills and deeper critical thinking. Collaborative learning refers to methods of learning in small groups, where students work together at various performance levels towards a common goal (Dillenbourg et al. 1996). Participating in a collaborative learning environment benefits several learning processes: the active exchange of ideas, critical thinking and engaging in discussion in a meaningful, personal and professional way. In addition, working together encourages participants to take responsibility for their own learning, resulting in increased understanding of their professional thinking and their skills as beginning professionals (Gokhale 1995; Dillenbourg et al. 1996; Wray 2007). Thus, learning and working together in peer meetings can provide a learning environment where reflection can be stimulated. In the studies mentioned above (Gokhale 1995; Thijs and van den Berg 2002; Meijer 2005; Tigelaar et al. 2006), the results are based on experienced professionals. We do not know whether participation in peer meetings also makes a positive contribution to the learning experiences of undergraduate students with regard to reflection.

A qualitative analysis of reflective essays was undertaken in order to gain an understanding of the role of peer meetings in students’ learning experiences. The following questions were analyzed:

-

(1)

What do students report with regard to learning about their personal experiences in peer meetings?

-

(2)

What do students report about the role of peer meetings in their learning experiences?

Methods

Study context and participants

The investigation was carried out in the Department of Speech Therapy at the Hanze University Groningen. Subjects were health sciences students participating in peer meetings guided by a coach. Peer meetings are integral to the longitudinal course of professional development. The aim of the meetings is to make students aware of themselves both as professionals and in relation to others in order to encourage the development of professional behaviour (Schaub-de Jong 2007).

Peer meetings involve a maximum of seven students, participating in eight sessions, each of which lasts for 90 min. Students discuss and analyze personal experiences from professional practice in a highly structured way. Each student presents an experience and one is selected for discussion. The students ask clarifying questions of the presenting student to which the latter must respond. Different approaches, advice and solutions may then be suggested. The presenting student selects a piece of advice or a solution that best fits his or her situation. At the end of the session the students evaluate what they have learned. The teachers intervene as little as possible to allow the collaborative reflection process to develop naturally. They may intervene in the discussion at the clarification stage to improve and encourage a deeper understanding of the experience presented for discussion. They may also provide supplementary analysis, perspectives or advice at the end of the meeting. Following each session, students write a report in which they reflect on their personal experiences during the meeting. In between the meetings, the teacher and the peers provide feedback on this reflection. Reflection and feedback stimulate the reflection process (Wong et al. 1995; Rogers 2001; Ash and Clayton 2004; Korthagen 2004). At the end of the course, students write a reflective essay which provides insight into the individual learning process experienced during the course (Mansvelder-Longayroux et al. 2007). The format for the reflective essay is described in the study manual and includes four topics:

-

The personal learning process, based on learning objectives, the subjects brought up for discussion and eight reflection reports

-

What the student explicitly learned from peers

-

Personal findings with regard to cooperation in the group and with the coach

-

Learning objectives for the next period in the peer meetings or for working in professional practice.

Material

The reflective essays of third and fourth-year students were analyzed in order to answer the research questions. At the first peer meeting, the students were informed about the investigation but did not receive any specific instruction regarding the role of the meetings. All third and fourth-year students participating in peer meetings (n = 84) were asked to present an anonymous copy of the reflective essay.

Analysis

To gain an insight in the different ways students experience learning and participation in peer groups a phenomenographic analysis was carried out (Åkerlind 2005). Phenomenographic analysis is a methodological approach to educational research in which the object of study is the variation in human meaning, understanding, conceptions, awareness or ways of experiencing a particular phenomenon (Åkerlind 2005). In this study we investigate in which way students experience, understand participation in a peer group, as the particular phenomenon.

The reflective essays were analyzed to the point of saturation (Miles and Huberman 1994) for expressions of personal learning and the role of peer meetings. As usual in phenomenographic research each expression is interpreted within the context of the group of expressions as a whole, in terms of similarities to and differences from other expressions.

The first author conducted the content analysis of the reflective essay and developed the coding scheme. The data were coded using open coding techniques (Miles and Huberman 1994), which entailed assigning names to items and combining related items into categories. Each category (primary outcome) reveals something distinctive about the way of understanding the role of the peer group and the categories are logically related (Åkerlind 2005).

The coding scheme was independently crosschecked by the third author who coded a number of reflective essays. Differences in coding were discussed with the first author, which resulted in adjustments to the learning interaction items. The number of codes decreased from 25 to 17. The code definitions were made more explicit and some items were combined. The findings were then discussed with the second and fourth authors.

Results

General

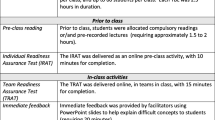

Seventy percent of the students (n = 59) participated. Saturation was reached after analyzing 26 reflective essays (n = 26). The coding process resulted in three categories of expression (Table 1): (1) learning experiences, (2) interactive learning and (3) conditions for a well-functioning group.

Learning experiences

In their reflective essays students reported that peer meetings helped them to better understand themselves, their skills, their professional thinking and their ability as beginning professionals. These expressions (Table 1 (1)) were divided into three subcategories: (a) personal learning experiences, (b) learning experiences relating to skills and (c) professional learning experiences.

Personal learning experiences

Students reported that sharing experiences resulted in personal learning experiences which they interpret as personal growth. Students also reported that peer meetings helped them towards (i) deeper thinking about themselves:

I have learned that there are certain patterns in my thinking, feeling and acting. Those patterns that occur time and again […] I am very preoccupied with expectations of other people in the adjustments I have to make. I have to change that […]. (student 1)

Students also think that they obtain (ii) additional perspectives on the subjects introduced for discussion:

My opinion is broadened in several areas by new points of view and I can understand how others look at something and why. Sometimes someone is so convincing that my opinion changes, in any case I gained more insight into the thoughts of other people … into what’s going on in their minds. (student 18)

Students reported that they were preoccupied with (iii) emotions and how they could best deal with them:

Time and again I realize that I am worrying for no reason. All the same, it still happens every time. For one reason or another, I’m not able to maintain my self-confidence at certain times. For me, this has everything to do with uncertainty and fear of failure. (student 14)

Skills

Participation in peer meetings creates an opportunity to experiment with skills such as learning to make mistakes, establishing distance, learning to be honest or to give your opinion. Students felt that practising these skills supported their personal and professional growth. They also reported becoming aware of their own skills and abilities when meeting clients during their internship. Thus two subcategories were identified in the skills category: (i) practising and (ii) empathy development.

The following student illustrates (i) practising: making mistakes is an opportunity to learn.

No one is perfect; you are allowed to make mistakes. Only then can you develop yourself. So I can practise and if I do something wrong I can try to change my behaviour as a consequence. (student 7)

Another student reported that clarifying experiences provided an opportunity to establish a distance from herself and from the experience.

During peer meetings you actually try to look at yourself from the outside. It provides a better way of analyzing. (student 13)

Students also mentioned experiences where they were able to put themselves in the patient’s position and develop empathy (ii):

I better understand the needs of that boy who is unsure of himself [client, MS] because of a better understanding of myself […] (student 10)

Professional learning experiences

In this category, students reported about learning experiences regarding their participation in peer meetings, which stimulated learning about professional functioning as a novice professional and freed them from difficulties they felt during the internship: discovering their profession.

By bringing up a situation without actually knowing what the problem was, it felt like a relief after the peer meeting. Because of this discussion I was later able to discuss what preoccupied me during the internship and to accept the situation. (student 21)

Interactive learning

In this category, students referred to interactions in the peer meetings. Students reported that they learned through processes of (a) interactive discussion and (b) interactive training.

Interactive discussion

This category contains two subcategories. Students mentioned that speaking about their experiences on a regular basis in peer meetings enabled them to let off steam and share feelings:

During the peer meeting one has the opportunity to let off steam, to ask questions and to hear from each other what’s going on. Most of the time the peer meeting is a resting point during the week. (student 13)

Understanding the experiences and feelings of group members encourages self- confidence. One student reported:

It was nice to share experiences of the internship with fellow students. I had a difficult start to my internship. I was left to my own devices, which was very unpleasant as in the beginning I needed coaching and assurance. It made me very restless and I always felt insecure about my actions and skills. I eventually brought this problem up in the peer meeting. I really needed the help of the group. (student 17)

Interactive training

Students reported that working in peer meetings gave them the opportunity to learn from the skills and experiences of others by facilitating discussion and interaction. Students thought that interactive training enhanced awareness of themselves and others by reacting to one another, (i) thereby stimulating one another’s thinking:

I was encouraged to look at myself because I was ‘forced’ to think about my own thinking, feeling and acting and to talk about it in the group […] Because of the questions from others I gave much more thought to the feelings and thoughts I had in that situation. I got a better view of myself. (student 23)

In this way, differences between group members in terms of skill level and knowledge and contributions to group processes contributed to the interactive training process in the group. Students reported that they learned from each other by being (ii) role models for each other:

I learned a lot from other students asking questions [reflection skill, MS]. Some students were able to phrase their questions in a professional manner. They made intriguing connections that I hadn’t thought of. I learned a lot from them. (student 19)

In addition, students mentioned that working together gave them the opportunity to (iii) develop their skills. Students mentioned that they trained themselves to listen better, to ask questions that were technically good, and to analyze the experience. One student reported that she wanted to train herself to listen better and ask questions:

I find it difficult to listen objectively to someone’s experiences without developing my own opinion. I realized that I thought in terms of problem solving too soon. When I started to clarify the experience, I asked in more depth […] (student 24)

Conditions for effective functioning

In addition to the categories identified above, the reflective essays also contained expressions where students referred to conditions necessary for a well-functioning group. Students identified two kinds of condition: (a) structural conditions and (b) social conditions.

Structural conditions

Students reported that peer meetings only functioned satisfactorily if the group functioned well. Safety was an important factor.

Only when the basis is satisfactory can peer meetings begin to work, which means that there is trust among the peers, that they keep to what is agreed on and that they discuss difficulties openly. (student 22)

Students also experienced group composition and size as factors affecting the functioning of the group:

As a negative issue this implied that the balance was sometimes lost in discussing a problem. Sometimes the quieter group members could barely participate because of the more dominant members. (student 25)

Students working in a larger group than they were accustomed to reported that they no longer felt comfortable:

After the group was split up I generally experienced a better and more relaxed level of cooperation […] It was possible to have a more intensive discussion of the problem and everyone had more of a chance to participate. (student 21)

Finally, students frequently referred to the role of the coach who guided the peer meetings. The expressions imply that the coach played an important role in encouraging reflection skills, depth of analysis, understanding and creating a safe learning environment.

She let us solve and clarify the problems by ourselves. She only helped us when we got stuck. So she wasn’t dominant in guiding […] She gave us a lot of space […] The atmosphere improved and I felt comfortable […] Also, the feedback we received was very pleasant […]. (student 1)

Social conditions

In almost all of the reflective essays, students referred to social conditions, which they saw as being essential for a well-functioning group. They mentioned that adhering to agreements and social etiquette, such as respect for one another, regard for one another and listening to one another, are important for an acceptable atmosphere.

Having regard for all the others, creating a safe environment. Everyone listened well to each other and worked hard to put the person who brought up the subject at ease. (student 3)

Discussion and conclusion

Students reported that they learned about their own personal and professional behaviour from participation in peer meetings. They even mentioned that discussing such subjects in the group gave them a better understanding of their behaviour. The role of peer meetings in this reflective process was also shown in student reports about the benefits of interactive discussions and the development of interpersonal skills. However, the students reported that conditions for effective peer meetings had to be met for these meetings to be beneficial.

These findings are in line with studies on the effects of collaborative learning. It appears that learning together helps students to understand themselves better, to refine their critical and professional thinking, as well as their ability as beginning professionals (Gokhale 1995; Wray 2007). The literature (Dillenbourg et al. 1996; Rogers 2001) also suggests that working together contributes positively to personal and professional learning experiences.

The presence of multiple perspectives on any one experience also corresponds to Kelchtermans and Hamilton’s (2004) proposed framework of teaching dimensions. An awareness of the possibility that there is more than one perspective in any interaction is a positive indication of the quality of reflection. These can be perspectives on moral issues regarding the justification of actions, or perspectives arising from different emotional responses to the situation, but might also be technical perspectives that arise in a given situation.

The findings on interactive learning in peer meetings tie in with study findings which indicate that social interaction promotes the development of students’ reflection skills (Thijs and van den Berg 2002; Tigelaar et al. 2006; Meijer 2005; Wray 2007). The engagement of peers helps participants realize that they are not alone. Finding support within the group structure makes them believe that they can rely on each other. Dealing with one another generates, maintains and restores positive feelings of wellbeing, self-confidence and commitment, thereby possibly creating a positive atmosphere which has a positive effect on learning processes (Vermunt and Verloop 1999).

The finding that the quality of group functioning is a prerequisite for quality of learning is in line with other literature which suggests that an affective learning climate during meetings will only be achieved if the atmosphere is perceived as trustful, safe and secure (Branch 2005; Boud and Walker 1998). In addition, Gokhale (1995) points out that the coach must view teaching as a process to develop and enhance the student’s ability to learn. In our investigation, all the peer meetings were intensively guided by a coach and students perceived the coach as playing an important role in encouraging learning and creating a safe learning environment. However, the coach’s actual influence on learning processes cannot be identified. As Van Velzen and Tillema (2004) and Boendermaker et al. (2003) also state, more research is needed to explore the influence of the coach. The style of coaching (directive versus liberal) and the coach’s ability to create a safe environment can be factors involved in increasing students’ reflection ability, as part of their professional attitude, through peer meetings.

The findings of this investigation are mainly based on expressions by students about learning with respect to gaining skills and changing behaviour. Korthagen (2004) suggests that this is a superficial type of reflection. Other research (Mansvelder-Longayroux et al. 2007; Van Velzen and Tillema 2004; Driessen et al. 2005) also shows that reflection often consists of superficial reports of events and a businesslike analysis. Training reflective skills should be aimed at a better understanding of skills and behaviour, which would include personal elements. Although students report personal aspects, it remains unclear whether participation in peer meetings results in the desired deeper reflective skills.

The strength and limitations of this study should be taken into account when interpreting the results. A first strength is the phenomenographic design. With this kind of methodological approach a range of meanings and perceptions is generated representing learning experiences in an area where there is a lack of empirical facts. The outcomes give positive indications of the role peer meetings can play in students’ learning experiences in relation to professional practice. Secondly, the explorative nature of the study gives deeper insight into the diversity of the learning experiences of students when participating in peer meetings. Students reported that peer meetings were a valuable condition and effective learning method for their professional development. Thirdly, in line with research about portfolio content (Pearson and Heywood 2004; Mansvelder-Longayroux et al. 2007), the content of the reflective essays in this study gave an insight into the individual learning processes of students. The reflective essay encourages the student to reflect on the learning process as a whole in terms of his or her professional development over a certain period.

One limitation is that the research was conducted in only one school. In our qualitative, explorative study this seems acceptable because the objective was to achieve an initial understanding of personal learning expressions and the role of peer meetings. A second limitation is that the student population was restricted to females. Ninety-eight percent of speech therapist students are female. A more heterogeneous group in terms of gender and type of training might have shown greater variation in items, implying saturation at a later point in time and resulting in a greater variety of expressions (Miles and Huberman 1994).

Our main conclusion is that there is a strong indication that students feel positively about learning experiences with regard to reflective skills developed through peer meetings. Confirmation is needed from research in broader target groups. The quality of the reflective skills acquired in peer meetings also needs further study. There is a rather strong indication regarding the quality of peer meetings. Further clarification is needed about the coach’s role. This investigation has generated useful criteria for such further research.

The outcomes of our study may also have implications for the use of peer meetings in practice. The findings give promising indications that peer meetings create an interactive learning environment in which students can learn about themselves, their skills and their abilities as novice professionals. These learning experiences may foster the development of their professional behaviour.

References

Åkerlind, G. S. (2005). Variation and commonality in phenomenographic research methods. Higher Education Research & Development, 24(4), 321–334. doi:10.1080/07294360500284672.

Arnold, L. (2002). Assessing professional behaviour: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Academic Medicine, 77, 502–513.

Ash, S. L., & Clayton, P. H. (2004). The articulated learning: An approach to guided reflection and assessment. Innovative Higher Education, 29(2), 137–154. doi:10.1023/B:IHIE.0000048795.84634.4a.

Boendermaker, P. M., Conradi, M. H., Schuling, J., Meyboom-de Jong, B., Zwierstra, R. P., & Metz, C. M. (2003). Core characteristics of the competent general practice trainer, a Delphi study. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 8, 111–116. doi:10.1023/A:1024901701831.

Boenink, A. D. (2006). Teaching and learning reflection on medical professionalism. Enschede: Gildeprint Drukkerijen B.V.

Boud, D., & Walker, D. (1998). Promoting reflecting in professional courses: The challenge of context. Studies in Higher Education, 23(2), 191–206. doi:10.1080/03075079812331380384.

Branch, W. T. (2005). Use of critical incidents reports in medical education. A perspective. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20, 1063–1067. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00231.x.

Dillenbourg, P., Baker, M., Blaye, A., & O’Malley, C. (1996). The evolution of research on collaborative learning. In E. Spada & P. Reiman (Eds.), Learning in humans and machine: Towards an interdisciplinary learning science (pp. 189–211). Oxford: Elsevier.

Driessen, E. W., van Tartwijk, J., Overeem, K., Vermunt, J. D., & van der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2005). Conditions for successful reflective use of portfolios in undergraduate medical education. Medical Education, 39, 1230–1235. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02337.x.

Gokhale, A. A. (1995). Collaborative learning enhances critical thinking. Journal of Technology Education, 7(1), 22–30.

Goldie, J., Dowie, A., Cotton, P., & Morrison, J. (2007). Teaching professionalism in the early years of a medical curriculum: A qualitative study. Medical Education, 41, 610–617. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02772.x.

Kelchtermans, G., & Hamilton, M. L. (2004). The dialectics of passion and theory: Exploring the relationship between self-study and emotion. In J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. Kubler LaBoskey & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (pp. 785–810). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Korthagen, F. A. J. (2004). In search of the essence of a good teacher: Towards a more holistic approach in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20, 77–97. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2003.10.002.

Mansvelder-Longayroux, D., Beijlaard, D., & Verloop, N. (2007). The portfolio as a tool for stimulating reflection by student teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23, 47–62. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.033.

Meijer, P. (2005). Tracing learning in intervision. Paper presented at the 32nd Dutch-Flemish Educational Research Days (ORD), Gent, Belgium.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). An expanded sourcebook. Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Pearson, D. J., & Heywood, P. (2004). Portfolio use in general practice vocational training: A survey of GP registrars. Medical Education, 38, 87–95. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2004.01737.x.

Rogers, R. R. (2001). Reflection in higher education: A concept analysis. Innovative Higher Education, 26, 37–57. doi:10.1023/A:1010986404527.

Schaub-de Jong, M. A. (2007). Effecten van reflectieonderwijs in een competentiegericht curriculum. Tijdschrift voor Hoger Onderwijs, 24, 229–238. What students learn from training reflective skills in a competence-based curriculum: A qualitative study.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Tigelaar, D. E. H., Dolmans, D. H. J. M., Meijer, P. C., de Grave, W. S., & van der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2006). Teachers’ interactions and their collaborative reflection process during peer meetings. Advances in Health Sciences Education (published online).

Thijs, A., & van den Berg, E. (2002). Peer coaching as part of a professional development program for science teachers in Botswana. International Journal of Educational Development, 22, 55–68. doi:10.1016/S0738-0593(00)00078-X.

van Velzen, J. H., & Tillema, H. H. (2004). Students’ use of self-reflective thinking: When teaching becomes coaching. Psychological Reports, 95, 1229–1238. doi:10.2466/PR0.95.7.1229-1238.

Vermunt, J. D., & Verloop, N. (1999). Congruence and friction between learning and teaching. Learning and Instruction, 9, 257–280. doi:10.1016/S0959-4752(98)00028-0.

Wong, F. K., Kember, D., Chung, L. Y., & Yan, L. (1995). Assessing the level of student reflection from reflective journals. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 22, 48–57. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.22010048.x.

Wray, S. (2007). Teaching portfolios, community, and pre-service teachers’ professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23, 1139–1152. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2006.10.004.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Schaub-de Jong, M.A., Cohen-Schotanus, J., Dekker, H. et al. The role of peer meetings for professional development in health science education: a qualitative analysis of reflective essays. Adv in Health Sci Educ 14, 503–513 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-008-9133-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-008-9133-3