Abstract

Further Neolithic encampments and settlements have been explored by the Combined Prehistoric Expedition in the Nabta Playa Basin on the South–Western Desert border around 100 km west of the Nile Valley. The perfectly preserved stratigraphic setting of the new site, numerous hearths and traces of dwellings, rich cultural material including pottery, radiocarbon dates and presence of bone remains render site E–06–1 an exception on the map of settlements of El Adam communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

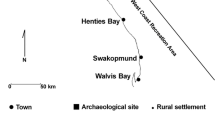

The Nabta Playa Basin is one of the largest palaeolakes of the playa type on the South–Western Desert border, located around 100 km west of the Nile Valley (Fig. 1). Remains of hundreds of Neolithic encampents and settlements have been found around it and excavated by the Combined Prehistoric Expedition (Wendorf and Schild 1980, 1998, 2001a; Banks 1984; Close 1987; Nelson et al. 2002). In 2006, a research project commenced that aimed at examining various aspects of the Early Neolithic settlement, beginning with the identification of its earliest phase. An extensive archaeological survey was carried out in the Nabta Playa Basin as part of that project.

Evidence of El Adam horizon settlement at Nabta had previously been recorded at three sites: E–75–9 (Wendorf and Schild 2001c), E–91–3 and E–91–4 (Close 2001). All of these sites are situated close to each other in the central part of the basin (Fig. 2). Exploration of a new site, E–06–1, located 600 m northwest of Site E–75–9, provided extraordinary results. It was a seasonal encampment situated on an Early Holocene phytogenic dune, at the edge of a seasonal playa lake appearing after summer rains, probably for several months a year (Fig. 3). The Early Holocene rains and subsequent seasonal lakes were the direct response of the considerable northward shift of the monsoonal rain belt (e.g., Haynes 1987; Pöllath and Peters 2007). Although partially truncated by recent wind erosion, the site is overlain by massive mid-Holocene silt formation heralding a major arid phase (compare Schild and Wendorf 2001), and preserved in an excellent state. So far, a dozen remains of dwellings, several dozen hearths and rich artefact assemblages have been excavated, including nearly 20,000 lithics, numerous bone remains, thousands of fragments of ostrich eggshells and beads made from them, as well as fragments of decorated ostrich eggshell containers. A discovery of eight potsherds, five of which were embedded in dated archaeological features, is very important. The site’s complex stratigraphy, including frequent overlapping hut basins, proves how attractive the place was and testifies to the fact that the settlers returned seasonally many times. Radiocarbon dates indicate that the huts were inhabited by a small group of people between 9200 and 9000 uncal year bp, thus ca. 8400–8000 (cal bc).

Natural Environment at the Beginning of Holocene

The end of the Pleistocene in the Western Desert was marked by an arid period lasting for tens of thousands of years. Climate changes from the end of the Last Glacial once again made it possible, following a long break, to settle in the desert (Kuper and Kröpelin 2006: 806).

During the humid interphase of the El Adam variant (ca. 9800/9500–8850 uncal year bp), the climate was relatively dry and not as favourable as during the subsequent Holocene optimum, yet summer rains (ca. 50–100 mm annually) were sufficient to fill seasonal lakes forming in deflation basins as well as to allow the expansion of modest vegetation and small- and medium-sized animals adapted to desert conditions (Wendorf and Schild 2006: 9). So far, very little information is available concerning the early Holocene flora. Scarce data come from two sites, E–77–7 at El Gebal El Beid Playa, some 40 km northeast of Gebel Nabta, and E–06–1, where botanical remains were recovered. At the former site, the following floral macroremains were identified: charcoal of Tamarix sp. (Barakat 2001: 596), charred seeds identified as wild millet (Panicum turgidum), a seed of a plant belonging to Paniceae and four seeds belonging to two taxa, possibly Leguminosae (Close and Wendorf 2001: 69; Wasylikowa et al. 2001: 606). Site E–06–1 provided Tamarix sp., Citrullus colocynthis and Echinochloa colona, while in one of the samples from Hearth 35, seeds of Poaceae grass were found (Maria Lityńska-Zając, personal communication).

The recovered flora with tamarisk is the only tree species indicated by Barakat (2001: 600); this suggests an environment similar to that of the extant small oases in the deserts of southern Egypt. The recently identified flora from Site E–06–1 has not changed this interpretation. Further to the south, however, at Selima, Oyo and El Atrun, Sudan, elements of Sahelian flora appear in the pollen samples dated to the lower early Holocene (e.g., Haynes et al. 1989).

Geomorphological and lithostratigraphic studies of the Kiseiba and Nabta Playa Areas have yielded additional characteristics of the environment. In the Kiseiba Area, the eponymous El Adam Playa contained the El Adam Sites E–79–8 and E–80/4 in the center, partially buried in slightly clayey sands (Schild and Wendorf 1984: 28). El Ghorab artifacts of the Lower Cultural Layer at Site E–79–4 were imbedded in similar sand in the center of El Ghorab Playa (Schild and Wendorf 1984). In Nabta Playa at Site E–75–6, a basin of a possible hut had cut into a phytogenic dune and was covered by the eolian sands of the same dune in the site’s lower cultural layer, assigned to the El Ghorab cultural/taxonomic variant (Schild and Wendorf 2001: 16). It is the same dune in which the remains of Site E–06–1 have been buried.

Both geomorphology and lithology indicate that the early Holocene space/time units of El Adam and El Ghorab are coeval with an environment in which the phytogenic dunes and eolian processes were still active. The heavily sandy textures of lacustrine (playa) deposits of this time suggest a lack of vegetation cover in the lands beyond playas and their shore zones. It is an ecological scenario well fitting a desert landscape with relatively large oasis-like, seasonal playas with wide shores and tamarisk trees, shrubs and grasses along the shores.

Osteological material from the El Adam settlements identified such species of animal as gazelle (Gazella dorcas and Gazella dama), hare (Lepus capensis), jackal (Canis aureus), turtle (Testudo sp.), birds (Otis tarda and Anas querquedula), big bivalve shells (Aspartharia rubens) of Nilotic origin and shells of snails (Bulinus truncatus and Zootecus insularis) (Gautier 2001: 611; Wendorf and Schild 2001c: 656). The most interesting and controversial are the remains of cattle, which could not really have survived in these conditions without human help.

Site E–06–1

New concentrations of burnt stones and a substantial number of artefacts were found on the surface, and their analysis showed that they belong to the El Adam horizon. Numerous bone remains indicated that the site was uncovered by wind a relatively short time before. During four seasons (2006–2009) 178 m2 were excavated altogether, which constitutes ca. 50–60 % of the site’s total area (Fig. 4).

The southwest part of the site was considerably deflated. The observed remains of hearths were circular, dark–grey sand spots without any charcoal. The area abounded in artefacts, which were present almost solely on the surface and probably represented a palimpsest of several telescoped settlement horizons. The site’s northern portion was a little better preserved, where the remains of hearths were visible as small concentrations of burnt rock and overlapping objects indicated the multiphase character of settlement. Fills contained grey sand and fine charcoal as well as lithics, fragments of animal bones, and ostrich eggshells together with beads made from the latter. Distinct traces of human activity reached the depth of 50–60 cm.

However, the most interesting portions were the central and western parts of the site. Hardly any artefacts were found on the surface, but after the layer of recent eolian and sheet wash sand was removed, overlapping outlines of dwellings became visible at the depth of 15–20 cm. The exploration revealed four to five settlement phases, which manifested themselves as dark grey, sometimes reddish layers, whose thickness varied between several and a dozen centimetres, separated by several centimetre-thick layers of sterile sand (Fig. 5). The layers, subsiding in the middle, probably constituted the floors of seasonal huts, subsequently covered with eolian sand deposited after they were abandoned. Their fills contained rather a modest number of artefacts, restricted to blanks, scant cores and tools predominated by backed pieces and relatively big end scrapers. A few pottery fragments, animal bone remains and ostrich eggshells (including the beads) were also found. They were probably small huts of approximately oval outlines, whose diameters varied between 2 and 3.5 m. Inside each was at least one small hearth. In several features, the remains of post holes and small pits for storing vessels were found. So far, 11 huts have been excavated, yet their total number may be greater as the stratigraphy seems to indicate with a great degree of probability that further huts may be waiting to be discovered at the site’s western and southwestern edge, i.e., in the part totally or at least partially covered by younger beds of lacustrine sediments.

The distribution of artefacts and post-consumption waste seems to indicate that distinct concentrations of hearths and the accompanying movable archaeological material found at the site are the remains of zones of economic activity situated outside rather than inside those small and cramped dwellings (Fig. 6).

Description of the Material

Lithics

The excavations provided nearly 14,000 flint artefacts, including 949 tools and 147 cores. The site’s complex stratigraphy and the differences between the material collected from the surface and found in the layers situated below necessitated the division of the material into three horizons. One was constituted by the surface and the layers of contemporary, loose, drifting sand blown over by the wind (Horizon III). Another horizon (II) comprised the layers located 0–10 cm below the surface, which provided mixed material. Horizon I was made by layers situated more than 10 cm below the site’s surface and reaching the floor of the cut and comprised the material connected with the oldest phases of the site’s occupation.

In terms of blanks, Eocene flint decisively predominates over chert, quartz, chalcedony, quartzite sandstone and basalt. The remaining raw materials, such as sandstone, agate and petrified wood, play an insignificant role in the inventory (Tables 1, 2 and 3). The analysis of blanks shows that, in all the horizons, the material of flake proportions distinctly predominates with the constant contribution of blades (Tables 1, 2 and 3). Similarly, flakes and blades from single–platform cores predominate everywhere; however, their proportions are the greatest in the oldest layers (over 70 % of blades and flakes). Debitage from the remaining types of cores played a considerably less significant role (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

Metric data for the debitage from Site E–06–1 are similar for all the horizons. Blanks are microlithic and never exceed 3 cm in length and 2 cm in width. Only blades from opposed platform cores are slightly bigger.

The site provided an overall number of 147 cores (Fig. 7). At all horizons, single platform forms predominate over multiplatform and opposed platform cores as well as the 90° specimens. The cores from the oldest settlement phase are characterised by the smallest mean dimensions. Most cores carried no traces of preparation except for striking platforms.

Site E–60–1 provided a rich collection of typical El Adam tools. As in the case of debitage and cores, the material was divided into at least two phases (Horizon I—older phase, Horizon II—mixed material, Horizon III—younger phase). In all, 949 tools or their fragments were recovered from the site. The greatest typological diversification is displayed by the material from the surface, which provided the majority, i.e., as many as 671 retouched artefacts.

The frequency of occurrence of individual types of tools from Site E–06–1 may be seen in Tables 4, 5 and 6. Flint and chert distinctly predominate at all horizons, reaching the highest proportions on the surface, 62.1 and 23.2 % respectively, constituting together over 85 % of the assemblage.

The general typological structure within individual horizons is roughly the same, with a distinct predomination of backed pieces, a great contribution of geometric microliths and end scrapers and constant presence of microburin technique. The differences manifest themselves in the presence of some types of tools (e.g., trapezes, which are primarily found in younger layers) or the frequency of occurrence of certain groups of tools, for instance the relatively great contribution of flakes and denticulated or notched blades in the material from the site’s surface (Table 4).

Among microliths (Figs. 7, 8 and 9), segments constituted the group predominating quantitatively at the deepest layers (typology according to Tixier 1963). The 15–20-cm layer provided a single specimen of trapeze. Trapezes are proportionately rare at El Adam sites, though they are encountered at most of them. The second most numerous group of geometric microliths were triangles, represented mainly by scalene forms.

As at the remaining El Adam sites, backed pieces constituted one of the most important and undoubtedly one of the most numerous categories of tools. They were characterised by a high level of manufacturing and a considerable typological diversity. At site E–06–1, two types—backed pieces with straight or arched backs—predominate decisively in all horizons.

Truncations are present in all horizons and comprised 5.7 % of tools from older layers, 4.8 % at Horizon II and 3.8 % on the surface. The microburin technique, predominating at site E–06–1, was used to produce backed pieces, truncations and geometrical tools.

Among other tools, end scrapers on flakes were decisively dominating and, typical for El Adam, some of them were made on collected Middle Palaeolithic blanks—most frequently made of quartzitic sandstone (Fig. 8). Burins were present at most El Adam sites (they did not occur at E–77–7, E–91–3 and E–91–4), yet they did not play a significant role, with the frequency of their occurrence varying between 1 and 3 %. At Site E–06–1, they occurred at all settlement horizons, but the collection acquired on the surface was the most numerous and diversified. Apart from the tool forms discussed above, the assemblage contained perforators, notched and denticulated pieces, as well as blades with discontinuous retouch.

Macrolithic Tools

The remaining archaeological material did not display significant typological differences between individual settlement horizons. The site provided six fragments of flat, basin-like matates made of sandstone, five complete forms and 33 fragments of handstones (manos), usually flat or discoid, and less frequently cube-shaped. The grinding stones were usually quite precisely made from carefully selected raw material (sandstone or quartzitic sandstone). The excavations also provided 18 hammerstones.

An interesting group is constituted by polishers used for polishing objects made of stone, horn, bone, eggshell or wood. A characteristic feature is the presence of a flat, slightly convex (sometimes concave), rough working surface. The surface bears traces of characteristic scratches or polishing, as well as the remains of raw material. At Site E–06–1, the polishers were made of sandstone; however, most of them survived only in fragments. The only complete specimen is a flat, flaked slab, whose working surface is a shallow, elongated groove running across almost the entire slab (Fig. 10b).

Tools known as calibrators were manufactured from very carefully selected raw material (fine-grained, relatively soft sandstone). Seven such calibrators were found at Site E–06–1, but they are known from several other sites (Connor 1984: 239; Close 1984: 346). Their common feature is the presence of at least one (sometimes several) ideally straight, groove-like, polished working surface of parallel edges, 8–15-mm wide, whose depth usually exceeds 4 mm (Fig. 10a). They were probably used to manufacture beads from ostrich eggshell (Connor 1984: 239), whose form and dimensions fit the calibrators’ working surfaces. Their use at the final stage of production—to polish a chain of linked, previously perforated beads—yielded a highly standardised final product. Such an interpretation is corroborated by the presence of hundreds of beads and their initial forms from various stages of processing at the site (Fig. 11). Similar tools are used by contemporary San from the Kalahari Desert in Namibia and Botswana (Lee 1984).

Pottery

One of the significant results of excavations at Site E–06–1 was finding in situ fragments of ceramic vessels (Jórdeczka et al. 2011). Pottery must have had varying and not only utilitarian significance, constituting an important identifying element of the traditions of individual human communities. Its presence in assemblages from El Adam is important also because it is a component of a new tradition observed in the Sahara whose origins still remain unknown.

According to Close (1995), pottery appeared in societies depending on aquatic resources and cereals, probably in the region spreading between the Nile and the Hoggar Mountains. Håland prefers to see its origin in the Nile Valley (2007: 170). For Huysecom et al. (2009): 915), pottery may have been invented in the present-day Sahel–Sudanese belt, while Jesse (2003: 35) indicates the southern Sahara, Sahel and Hoggar Mountains.

The El Adam variant of pottery is known in the Nabta Playa–Kiseiba basins from six sites: E–75–9 (Wendorf and Schild 2001b: 109); E–77–7 (Close and Wendorf 2001: 68); E–79–8 (Connor 1984: 239–44); E–80–4 (Close Close 1984: 346); E–91–3 (Close 2001: 79); and E–06–1 (Jórdeczka et al. 2011; Fig. 12).

The pottery from Site E–06–1 is characterised by the reddish colour of the exterior and high proportion (30–50 %) of relatively coarse mineral temper. Zedeño, who did extensive studies of the production technology of pottery in the Nabta–Kiseiba region, found that the Early Holocene pottery was made from locally available material (Zedeño 2002; Nelson 2002a). Vessel forms from the southern region of Egypt’s Western Desert were highly standardised at that time. They were solely bowls of various sizes and depths with varying wall thickness (Nelson 2002a: 2). Only one rim was found at Site E–06–1; it was a part of a bowl ca. 38 cm in diameter (Jórdeczka et al. 2011: 106, fig. 9). All the vessel fragments (n = 8, five of which were in situ) acquired so far from Nabta Playa Site E–06–1 display the same surface treatment. The patterns consist of lines, parallel to the rim and located at the same distance to one another (ca. 6–9 mm measuring from the centre of the line), which differ in the composition and shape of impressions. Bigger sherds show that the impression pattern repeats itself every four lines, which may mean that the potter had at least four tools (toothed disks?—compare Jórdeczka et al. 2011) for making impressions. An almost identical character of patterned impressions is visible on a pottery sherd from Site E–77–7 at El Gebal El Beid Playa (Close and Wendorf 2001: 68) and E–75–9 (Schild and Wendorf 2001: 109, Nelson 2002b: fig. 3).

Faunal Remains

Results of zooarchaeological analyses, carried out by Marta Osypińska from the Polish Academy of Science, confirm the data acquired at other El Adam culture sites. Wild mammals were the basic source of meat for local communities. Osteological materials showed that the highest contribution of bone fragments was from the dorcas gazelle (Gazella dorcas—295 fragments, 63 %). The second most numerous group of the excavated remains was the Cape hare (Lepus capensis—106 fragments, 22.6 %). The contributions of the remaining two species—dama gazelle and cattle, whose subspecies have not been precisely determined, did not exceed 10 % (Gazella dama—38 fragments, 8.1 %; Bos spp.—29 fragments, 6.2 %). Most of the Bos spp. remains (24) came from the surface of the site, but some of them (4) were found within one of the huts (Feature 6). Additionally, several shells of landsnail (Zoothecus) were also identified. A great number of ostrich eggshells were found at the site (>80 % of all the faunal remains), which was also characteristic for most Early Holocene sites in the Western Desert. Typically, the bones of the ostrich itself were absent.

The bones of large bovids present in several excavated Early Holocene sites have caused animated discussion on the domestication of Bos primigenius in the eastern Sahara (e.g., Gautier 1984, 1987, 2001, 2007; Smith 1984, 1986, 1992, 2005; Clutton-Brock 1993; Wendorf and Schild 1994, 2003; Wendorf et al. 1987; Muzzolini 1993; Close 1996; Schild and Wendorf 2001; Marshall and Hildebrand 2002; Wengrow 2003; Schild and Wendorf 2010). The hypothesis of domestication was published for the first time in 1976 (Wendorf et al. 1976: 106). It was based on a small number of bones from the not yet very precisely dated Neolithic sites in Nabta Playa. A more detailed description of the finds appeared a few years latter (Gautier 1980: 332). The report contained osteometric data implying domestication as well as the suggestion that the very low carrying capacity of the area precluded the possibility that it was inhabited by large wild ungulates. No such assemblages containing aurochs have ever been reported from pre-Neolithic Africa. Even the hartebeest, a faithful companion of auroch in the Nile Valley, was not present in the South-Western Desert (cf. Gautier 2001: 629), although its tolerance of aridity is greater than that of cattle (Kingdon 1982), as cattle need to drink water every other day. This reasoning led to the proposition that the early Neolithic bovids of Nabta could have been introduced to this inhospitable environment through human practice. Further work at Nabta Playa, especially between 1990 and 2003, yielded additional material pertaining to large bovid remains. Osteometric data indicate that the early Neolithic bovids appear to cluster in the size ranges of smaller aurochs studied in the Upper Egyptian Nile Valley and Lower Nubia (Gautier 2001: 628). On the other hand, the middle and late Neolithic cattle show a further shift to smaller sizes beyond the range of wild cattle in the Nile Valley. According to Gautier (2001: 628), this slow decrease in size of the early cattle is the same as that demonstrated by Helmer (1994) for early cattle in the northern Levant.

It has been implied that the early Neolithic South-Western Desert bovids might well be African buffalo (Smith 1984: 319; see also Grigson 2000). However, considering the harsh environmental conditions in the region and the sizable water requirement of African buffalo, one would have to assign domestic status to the beast. Grigson (2000), on the other hand, postulated that the osteometric and ecological data were weak because the available samples were too small. But more recent osteomorphic studies of the new materials recovered between 1990 and 2003 prompted Gautier (2001: 627; 2007: 78) to reaffirm his original assignment of the Nabta/Kasiba bovid remains to taurine cattle.

In more recent periods, a number of new data provided by DNA studies suggest an independent African center of early cattle domestication (e.g., Bradley et al. 1996; Hanotte et al. 2002; Edwards et al. 2004; Beja-Pereira et al. 2006) on one hand, and/or support the idea of one Near Eastern center of the taurine cattle domestication, on the other. A possibility of local introgression from wild aurochs (compare summary in Achilli et al. 2008) has also been considered.

Studies in linguistic stratigraphy of Nilo-Saharan languages by Ehret (1993, 2001, 2006) indicate a very early appearance of words pertaining to cattle pastoralism in the eastern Sahara, perhaps before 8500 bc. It preceded the emergence of words relating to sorghum cultivation. A precise dating of root words, however, can be deceptive and often has been criticized (e.g., cf. Bechaus-Gerst 2000; Gautier 2007: 81). If the words relating to sorghum cultivation are indeed younger than those linked to cattle keeping, one would estimate their age as preceding the El Nabta/Al Jerar Humid Interphase in the South-Western Desert, dated to between ca. 8050 uncal. bp and ca. 7300 uncal. bp, and identified with the Holocene climatic optimum in that desert (Schild and Wendorf 2001; Wendorf et al. 2007:211). At Nabta Playa, that was the time of large organized settlements with multifamily huts and bell-shaped storage pits. Nabta Site E–75–6 yielded over 20,000 macrofloral remains (seeds, rhizomes, etc.) belonging to at least 129 species, and 21 taxa identified to the level of species (Wasylikowa et al. 2001: 349). The seed assemblages found in particular huts formed four discrete units dominated by certain taxa: sorghum; gramineae; and mixed assemblages (Wasylikowa et al. 2001: 576). The assemblages suggest a broad-spectrum mass gathering of food plants with a preference for sorghum. Although palaeoecological causes for sorghum predominance over other grasses have not been made clear, this phenomenon may be best explained by the proposition that sorghum could have been cultivated (compare Wasylikowa et al. 2001: 591; Schild and Wendorf 2001: 660).

Recently, Chaix and Honegger (2011) and Linseele and Chaix (2011) reported the discovery of domestic cattle just about 350 km northwest of the Nabta Playa/Kiseiba basins in Wadi el-Arab, Kerma Area, Northern Sudan. The site presents a long sequence of archaeological beds firmly placed between about 8200 and 6500 cal. years bc. In the sequence, the first domestic cattle remains appear about 7200 cal. years bc. These dates would place the Kerma Area finds of the taurine cattle somewhere in the very end of the El Adam occupation of the South-Western Desert and/or in the subsequent dry Post-El Adam Arid Phase, certainly before the appearance of the El Ghorab settlers in the same area (Schild and Wendorf 2001: 52). These dates are largely similar to those accepted for the early domesticated cattle in the Near East. To Linseele and Chaix (2011), the discovery of early domestic cattle near the Third Cataract confirms the possibility of local cattle domestication in the Kiseiba/Nabta Areas. It seems that often contradicting interpretations of the DNA complex lineages and early dates for more or less putative domestic cattle in Northern Africa open doors to a great number of scenarios of repetitive external introduction of cattle, local aurochs domestication and cross breeding (cf. e.g., Chaix and Honegger 2011; Gautier 2007: 82).

Chronology

Excavations at Site E–06–1 provided five radiocarbon dates, which fit the chronological brackets outlined for the El Adam horizon on the basis of excavations at other sites (Fig. 13). One of them (9020 ± 140 bp) was determined on the basis of a charcoal sample retrieved in a stratigraphic trench at a depth of 85 cm. The youngest date (8980 ± 70 bp) comes from the hearth denoted as H13, from the horizon ca. 10–15 cm below the contemporary surface. The hearth was connected with or covered one of the younger phases of occupation at the site. The remaining dates, from a short period of time, between 9210 ± 50 and 9170 ± 50 uncalibrated bp years, are directly connected with the recovered dwellings (Fig. 5).

Conclusions

The perfectly preserved stratigraphic setting of the site, numerous hearths and traces of dwellings, rich cultural material including pottery, radiocarbon dates and the presence of several large bovid remains, presumably of early domestic cattle, render Site E–06–1 an exception on the map of settlements of El Adam communities. It opens new perspectives for the study of Early Holocene colonisation of the Western Desert by the first hunter–gatherer–cattle-keepers. Analysis of technology and stylistic features of the inventories from the discussed entity prove that its roots should be searched in the Arkinian—a Late–Palaeolithic complex from Lower Nubia, from the flooded village of Arkin, situated ca. 80 km southeast of Nabta Playa (Schild et al. 1968). Its oldest horizon is dated to the period of 10,900–10,400 cal bc (Wendorf et al. 1979), while its younger, identified phases have not yet been radiocarbon dated. It is true that no pottery has been found at the Arkin sites, yet the absence may have resulted from a very limited range of excavations. There is, however, an important link between the El Adam and the Arkinian populations. Today, it appears that it was in the Nile Valley that the first attempts were made to domesticate/tame the aurochs.

References

Achilli, A., Olivieri, A., Pellecchia, M., Uboldi, C., Colli, L., & Al-Zahery, N. (2008). Mitochondrial genomes of extinct aurochs survive in domestic cattle. Current Biology, 18, R157–R158.

Banks, K.M. (1984). Climates, cultures and cattle. The Holocene archaeology of the eastern Sahara. Department of Anthropology, Institute for the Study of Earth and Man, Southern Methodist University, Dallas

Barakat, H. (2001). Anthracological studies in the Neolithic sites of Nabta Playa, South Egypt. In F. Wendorf & R. Schild and Associates (Eds.), Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara, vol. 1. The archaeology of Nabta Playa (pp. 592–600). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Bechaus-Gerst, M. (2000). Linguistic evidence for the prehistory of livestock in Sudan. In R. M. Blench & K. C. MacDonald (Eds.), The origins and development of African livestock: Archaeology, genetics, linguistics and ethnography (pp. 449–461). London: UCL Press.

Beja-Pereira, A., Caramelli, D., Lalueza-Fox, C., Vernesi, C., Ferrand, N., Casoli, A., et al. (2006). The origin of European cattle: Evidence from modern and ancient DNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciances of the United States of America, 103(21), 8113–8118.

Bradley, D. G., Machuhg, D. E., Cunningham, P., & Loftus, R. T. (1996). Mitochondrial diversity and the origin of African and European cattle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 93, 5131–5135.

Chaix, L., & Honegger, M. (2011). New data on the transition from Mesolithic to pastoral economy in the Sudan: The case of Wadi El-Arab. Origin and early development of food producing cultures in Northeastern Africa—30 years later. Poznan 3–7 July 2011. Abstracts (pp. 8–9). Poznan: Poznan Archaeological Museum.

Close, A. E. (1984). Report on Site E-80-4. In A. E. Close (Ed.), Cattle-keepers of the Eastern Sahara: The Neolithic of Bir Kiseiba (pp. 325–349). Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press. F. Wendorf & R. Schild (assemblers).

Close, A.E. (1987). Preface. In: A.E. Close (Ed.), Prehistory of arid North Africa. Essays in Honor of Fred Wendorf. Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, pp. xi–xvi

Close, A. E. (1995). Few and far between. Early ceramics in North Africa. In W. K. Barnet & J. W. Hoopes (Eds.), The emergence of pottery. Technology and innovation in ancient societies (pp. 23–37). Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Close, A. E. (1996). Plus ça change. The Pleistocene-Holocene transition in Northeastern Africa. In L. G. Straus, B. V. Eriksen, J. M. Erlandson, & D. R. Yesner (Eds.), Humans at the end of the Ice Age. The archaeology of the Pleistocene-Holocene transition (pp. 43–60). London: Plenum Press.

Close, A. E. (2001). Site E-91-3 and E-91-4: The early Neolithic of El Adam Type at Nabta Playa. In F. Wendorf & R. Schild (Eds.), Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara, vol. 1. The archaeology of Nabta Playa (pp. 71–97). Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press.

Close, A. E., & Wendorf, F. (2001). Site E-77-7 revisited: The early Neolithic of El Adam Type at El Gebal El Beid Playa. In F. Wendorf & R. Schild (Eds.), Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara (The archaeology of Nabta Playa, Vol. 1, pp. 57–71). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Clutton-Brock, J. (1993). The spread of domestic animals in Africa. In T. Shaw, P. Sinclair, B. Andah, & A. Okpoko (Eds.), The archaeology of Africa: Food, metals and towns (pp. 61–70). London: Routledge.

Connor, D. R. (1984). Report on Site E-79-8. In A. E. Close (Ed.), Cattle-keepers of the eastern Sahara: The Neolithic of Bir Kiseiba (pp. 217–250). Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press. F. Wendorf & R. Schild (Assemblers).

Edwards, C. J., McHugh, D. E., Dobney, K. M., Martin, L., Russell, N., Horwitz, L. K., et al. (2004). Ancient DNA analysis of 101 cattle remains: Limits and prospects. Journal of Archaeological Sciences, 31(6), 695–710.

Ehret, C. (1993). Nile-Saharans and the Saharo-Sudanese Neolithic. In T. Shaw, P. Sinclair, B. Andah, & A. Okpoko (Eds.), The archaeology of Africa: Food, metals and towns (pp. 104–125). London: Routledge.

Ehret, C. (2001). A comparative historical reconstruction of Proto-Nilo-Saharan. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Ehret, C. (2006). Linguistic stratigraphies and Holocene history in Northeastern Africa. In K. Kroeper, M. Chłodnicki, & M. Kobusiewicz (Eds.), Archaeology of early Northeastern Africa. In memory of Lech Krzyżaniak (pp. 1019–1055). Poznan: Poznan Archaeological Museum.

Gautier, A. (1980). Contribution to the archaeozoology of Egypt. In F. Wendorf, & R. Schild (Eds.), Prehistory of the Eastern Sahara (pp. 317–344). New York: Academic Press.

Gautier, A. (1984). Archaeozoology of the Bir Kiseiba region, Eastern Sahara. In F. Wendorf & R. Schild (Eds.), Cattle-keepers of the Eastern Sahara (pp. 49–75). Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press.

Gautier, A. (1987). Prehistoric men and cattle in North Africa: A dearth of data and a surfeit of models. In A. E. Close (Ed.), Prehistory of arid North Africa. Essays in honor of Fred Wendorf (pp. 163–188). Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press.

Gautier, A. (2001). The early to late Neolithic archeofaunas from Nabta and Bir Kiseiba. In R. Schild & F. Wendorf (Eds.), Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara, vol. 1, The archaeology of Nabta Playa (pp. 609–635). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Gautier, A. (2007). Animal domestication in North Africa. In M. Bollig, O. Bubenzer, R. Vogelsang, & H.-P. Wotzka (Eds.), Aridity, change and conflict in Africa (pp. 75–90). Köln: Heinrich Barth Institut.

Grigson, C. (2000). Bos africanus (Brehm)? Notes on the archaeozoology of the native cattle of Africa. In R. M. Blench & K. C. MacDonald (Eds.), The origins and development of African livestock: Archaeology, genetics, linguistics and ethnography (pp. 38–60). London: UCL Press.

Håland, R. (2007). Porridge and pot, bread and oven: Food ways and symbolism in Africa and the Near East from the Neolithic to the present. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 17(2), 165–182.

Hanotte, O., Bradley, D. G., Ochieng, J. W., Verijee, Y., Hill, E. W., & Rege, J. E. O. (2002). African pastoralism: Genetic imprints of origins and migrations. Science, 296, 336–339.

Haynes, C. V. (1987). Holocene migration rate of the Sudano-Sahelian wetting front, Arba’in Desert, Eastern Sahara. In A. E. Close (Ed.), Prehistory of arid North Africa. Essays in honor of Fred Wendorf (pp. 69–84). Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press.

Haynes, C. V., Eyles, C. H., Pavlish, L. A., Richtie, J. C., & Rybak, M. (1989). Holocene palaeoecology of the eastern Sahara: Selima Oasis. Quaternary Science Review, 8, 109–136.

Helmer, D. (1994). La domestication des animaux d’embuche dans le Levant Nord (Syrie du Nord et Sinjar) du milieu du IXe millénaire BP. Nouvelles données d’après les fouilles recent. Anthropozoologica, 20, 41–54.

Huysecom, E., Rasse, M., Lespez, L., Neumann, K., Fahmy, A., Ballouche, A., et al. (2009). The emergence of pottery in Africa during the tenth millennium cal BC: New evidence from Ounjougou (Mali). Antiquity, 83, 905–917.

Jesse, F. (2003). Early ceramics in the Sahara and the Nile Valley. In L. Krzyżaniak and Associates (Eds.), Cultural markers in the later prehistory of northeastern Africa and recent research (pp. 35–50). Poznan: Poznan Archaeological Museum.

Jórdeczka, M., Królik, H., Masojć, M., & Schild, R. (2011). Early Holocene pottery in the Western Desert of Egypt. New data from Nabta Playa. Antiquity, 85, 99–115.

Kingdon, J. (1982). East African mammals. An atlas of evolution in Africa (Vol. III, Part D (Bovids)). London: Academic Press.

Kuper, R., & Kröpelin, S. (2006). Climate-controlled Holocene occupation in the Sahara: Motor of Africa’s evolution. Science, 313, 803–807.

Lee, R. B. (1984). The Dobe !Kung. New York: CBS College Publishing.

Linseele, V., & Chaix, L. (2011). Recent archaeozoological data on early food production in northeastern Africa. Origin and early development of food producing cultures in Northeastern Africa—30 years later, Poznan 3–7 July 2011 Abstracts, p. 17. Poznan: Poznan Archaeological Museum.

Marshall, F., & Hildebrand, E. (2002). Cattle before crops: The beginnings of food production in Africa. Journal of World Prehistory, 16, 99–143.

Muzzolini, A. (1993). The emergence of a food-producing economy in the Sahara. In T. Shaw, P. Sinclar, B. Andah, & A. Okpoko (Eds.), The archaeology of Africa: Food, metals and towns (pp. 227–239). London: Routledge.

Nelson, K. (2002a). Introduction. In K. Nelson & Associates (Ed.), Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara. Vol. 2. The pottery of Nabta Playa (pp. 1–8). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Nelson, K. (2002b). Ceramic assemblages of the Nabta-Kiseiba Area. In K. Nelson & Associates (Ed.), Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara, vol. 2. The pottery of Nabta Playa (pp. 21–50). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Nelson, K., Gatto, M. C., Jesse, F., & Zedeño, M. N. (2002). Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara. Vol. 2. The pottery of Nabta Playa. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Pöllath, N., & Peters, J. (2007). Holocene climatic change, human adaptation and landscape degradation in arid Africa as evidenced by the faunal record. In O. Bubenzer, A. Bolten, & F. Darius (Eds.), Atlas of cultural and environmental change in arid Africa (pp. 64–67). Köln: Heinrich Barth Institut.

Schild, R., Chmielewska, M., & Więckowska, H. (1968). The Arkinian and Shamarkian industries. In F. Wendorf (Ed.), The prehistory of Nubia (Vol. 2, pp. 651–767). Dallas: Fort Burgwin Research Center and Southern Methodist University.

Schild, R., & Wendorf, F. (1984). Lithostratigraphy of Holocene lakes along the Kiseiba Scarp. In A. E. Close (Ed.), Cattle-keepers of the Eastern Sahara: The Neolithic of Bir Kiseiba (pp. 9–40). Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press. F. Wendorf & R. Schild (Assemblers).

Schild, R., & Wendorf, F. (2001). Geomorphology, lithostratigraphy, geochronology and taphonomy of sites. In F. Wendorf & R. Schild (Eds.), Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara, vol. 1. The archaeology of Nabta Playa (pp. 11–50). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Schild, R., & Wendorf, F. (2010). Late Paleolithic hunter-gatherers in the Nile Valley of Nubia and Upper Egypt. In E. A. A. Garcea (Ed.), South-eastern Mediterranean peoples between 130,000 and 10,000 years ago (pp. 89–126). Oxford and Oakville: Oxbow.

Smith, A. B. (1984). The origins of food production in Northeast Africa. In J. A. Coetzee & E. M. van Zinderen Bakker (Eds.), Palaeoecology of Africa (16th ed., pp. 317–324). Rotterdam: Balkema.

Smith, A. B. (1986). Cattle domestication in North Africa. African Archaeology, 4, 197–203.

Smith, A. B. (1992). Pastoralism in Africa: Origins and development ecology. London: Hurst.

Smith, A. B. (2005). Desert solitude: The evolution of ideologies among pastoralists and hunter-gatherers in arid North Africa. In P. Veth, M. Smith, & P. Hiscock (Eds.), Desert people: Archaeological perspectives (pp. 261–275). Padstow: Blackwell.

Tixier, J. (1963). Typologie de l’Epipaléolithique du Maghreb. Mémoires du centre de recherches anthropologiques, préhistoriques et ethnographiques d’Alger. Mémoire No. 11, p. 42. Paris: Arts et Métiers Graphiques

Wasylikowa, K., Barakat, H.N. & Lityńska-Zając, M. (2001). Part IV: Nabta Playa Sites E-75-8, E-91-1, E-92-7, E-94-1, E-94-2, and El Gebel El Beid Playa Site E-77-7: Seeds and fruits. In F. Wendorf, R. Schild & Associates. Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara, vol. 1. The archaeology of Nabta Playa. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum, pp. 544–591

Wendorf, F., Close, A. E., & Schild, R. (1987). Early domestic cattle in the Eastern Sahara. In J. A. Coetzee (Ed.), Palaeoecology of Africa (18th ed., pp. 441–448). Rotterdam: Balkema.

Wendorf, F., Karlén, W., & Schild, R. (2007). Middle Holocene environments of North and East Africa, with special emphasis on the African Sahara. In D. G. Anderson, K. A. Masch, & D. H. Sandweis (Eds.), Climate change and cultural dynamics. A global perspective on mid-Holocene transitions (pp. 189–227). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Wendorf, F., & Schild, R. (1980). Prehistory of the Eastern Sahara. New York: Academic Press.

Wendorf, F., & Schild, R. (1994). Are the early Holocene cattle in the Eastern Sahara domestic or wild? Evolutionary Anthropology, 3, 118–128.

Wendorf, F., & Schild, R. (1998). Nabta Playa and its role in northeastern African prehistory. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 17, 97–123.

Wendorf, F., & Schild, R. (2001a). Introduction. In F. Wendorf & R. Schild & Associates (Eds.), Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara, vol. 1. The Archaeology of Nabta Playa (pp. 1–10). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Wendorf, F. & Schild, R. (2001b). Site E-75-9: The excavation of an El Adam(?) Early Neolithic Settlement at Nabta Playa. In F. Wendorf, R. Schild & Associates. Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara, Vol. 1, The Archaeology of Nabta Playa. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum, pp. 97–110

Wendorf, F., & Schild, R. (2001c). Conclusions. In F. Wendorf & R. Schild (Eds.), Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara, vol. 1. The archeology of Nabta Playa (pp. 648–676). Dallas: Southern Methodist University. Associates.

Wendorf, F., & Schild, R. (2003). Food economy and settlement system during the Neolithic in the Egyptian Sahara. In L. Krzyżaniak, K. Kroeper, & M. Kobusiewicz (Eds.), Cultural markers in the later prehistory of northeastern Africa and recent research. Studies in African Archaeology (Vol. 8, pp. 145–157). Poznan Archaeological Museum: Poznan.

Wendorf, F., & Schild, R. (2006). The emergence of village settlements during the early Neolithic in the Western Desert of Egypt. Adumatu, 14, 7–22.

Wendorf, F., Schild, R., & Haas, H. (1979). A new radiocarbon chronology for prehistoric sites in Nubia. Journal of Field Archaeology, 6, 219–223.

Wendorf, F., Schild, R., Said, R., Haynes, C. V., Gautier, A., & Kobusiewicz, M. (1976). The prehistory of the Egyptian Sahara. Science, 139, 103–104.

Wengrow, D. (2003). Review article: On desert origins for the ancient Egyptians. Antiquity, 79, 597–601.

Zedeño, M. N. (2002). Neolithic ceramic production in the eastern Sahara of Egypt. In K. Nelson and Associates (Eds.), Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara. Vol. 2. The pottery of Nabta Playa (pp. 51–64). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for research permission granted by the Antiquities Services of the Republic of Egypt.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Jórdeczka, M., Królik, H., Masojć, M. et al. Hunter–Gatherer Cattle-Keepers of Early Neolithic El Adam Type from Nabta Playa: Latest Discoveries from Site E–06–1. Afr Archaeol Rev 30, 253–284 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-013-9136-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-013-9136-1