Abstract

Endometriosis is a common problem in women in their reproductive years but is much less frequent in the postmenopausal state, with an incidence of around 2%. Malignant change in endometriotic deposits was first described by Sampson in 1925. Since then, the risk of malignant transformation has been well documented but continues to be a relatively rare occurrence, occurring mainly (79%) in the ovary. The vast majority of women with this condition are premenopausal or taking exogenous hormones. We undertook a retrospective review of hospital notes identified from our database of endometriosis cases undergoing surgery. We identified two cases of benign disease and two cases of endometriosis-associated adenocarcinoma presenting in menopausal women. The first patient presented with haematuria and rectal bleeding. At laparotomy, she was found to have a substantial endometriotic nodule involving the bladder and sigmoid colon. The second patient presented with abdominal pain and dyschezia. She was found to have uterosacral disease at laparoscopy. The third patient presented with an inoperable endometrioid adenocarcinoma, having previously had a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The fourth patient presented with pain and an abdominal mass. At laparotomy there was stage IV endometriosis, and histology subsequently revealed an ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma. In conclusion, endometriosis can arise de novo in the menopause, perhaps triggered by peripheral conversion of androstenedione or as a consequence of hormone replacement. Persistence of endometriosis past the menopause raises the risk of malignancy. Future research will help to differentiate between those who require radical treatment and those who can be managed conservatively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Endometriosis is a common problem in the reproductive years, with an incidence of 21% amongst women being investigated for infertility [1]. However, it is much less frequent in postmenopausal women, with an incidence of 2–4% [2]. First described by Sampson in 1925 [3], malignant change in endometriotic deposits is even less common, occurring mainly in the ovary (79%). Of those affected, the vast majority are premenopausal or are taking exogenous hormones. Here in the largest series reported to date, we report four cases of endometriosis presenting in postmenopausal women, including two cases of malignant transformation.

Case 1

A 46-year-old menopausal woman presented with haematuria and rectal bleeding. She was already known to have had endometriosis and had previously undergone a left salpingo-oophorectomy at age 23, followed by a total abdominal hysterectomy and right salpingo-oophorectomy at age 40. Although initially compliant with hormone therapy replacement (first estradiol implants, then Evorel 50 patches), she had stopped taking it 12 months prior to presentation. A cystoscopy was performed and bladder biopsies taken. These confirmed endometriosis. Subsequent imaging with computed tomography suggested a left-sided pelvic mass. She underwent laparotomy, where she was found to have a 5-cm endometriotic nodule in the sigmoid that was adherent to the bladder. The affected sigmoid and bladder were excised and sent for histology. This revealed florid endometriosis with polypoid endometrial mucosal lesions with vascular invasion involving both bowel and bladder.

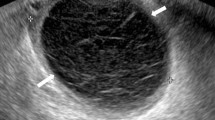

Case 2

A 56-year-old woman presented with abdominal pain and dyschezia. She had gone through the menopause at age 46 and although starting hormone replacement at that time, she had persisted with it for only 3 months. A sigmoidoscopy and barium enema were normal. Her symptoms persisted, and she underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy. This revealed endometriosis on both uterosacral ligaments (Fig. 1). Excision biopsies were performed, which revealed endometrial-type glands and stroma consistent with endometriosis.

Case 3

A 55-year-old woman presented with severe dyschezia and vaginal bleeding. Seven years earlier she had undergone a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for endometriosis and fibroids. Five years following this initial procedure, she underwent excision of a vault endometrioma, which was confirmed on histology. On magnetic resonance imaging she was found to have a 10-cm mass arising from the vaginal vault. At laparotomy, she was found to have a frozen pelvis with a 10-cm inoperable fungating tumour extending into the upper third of the vagina. A frozen section revealed an endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

Case 4

A 54-year-old postmenopausal woman presented with pain and an abdominal mass. She had gone through the menopause at age 46 and was not taking any hormone replacement. Premenopausally, she had a history of endometriosis and had previously had an ovarian endometrioma excised at laparotomy. Her CA125 was 22 u/ml at presentation. At laparotomy there was stage IV endometriosis and what appeared to be an ovarian tumour densely adherent to the fundus of the uterus. There was no evidence of tumour spread outside the ovary or uterus. She underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and omentectomy. Peritoneal washings were negative. Histology revealed a moderately differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma involving the ovary and the uterine fundus. Endometriosis was present on the contralateral ovary. There was no evidence of tumour arising from the endometrial cavity. The appearances suggested malignant transformation of endometriosis.

Discussion

The aetiology and pathophysiology of endometriosis is complex, and its origins remain controversial. It is, however oestrogen dependent, and as such the natural history of the condition is of regression in the menopause. A retrospective analysis of 903 patients operated on with endometriosis revealed a prevalence of 2.2% in postmenopausal women [2]. Postmenopausal presentation is usually associated with hormone replacement therapy [4], and in one case it was reported to occur de novo 17 years after oestrogen replacement was taken following hysterectomy [5]. It has also been reported in obese postmenopausal women, presenting as bowel obstruction secondary to sigmoid endometriosis; in this report the proposed mechanism was activation of endometrium by high levels of circulating oestrone derived from the peripheral conversion of androstenedione to oestrone in adipose tissue [6]. Interestingly, endometriosis has also been reported in postmenopausal women taking anti-oestrogens. Tamoxifen is a selective oestrogen receptor modulator that exerts an anti-oestrogenic effect on the breast but a weakly oestrogenic effect on the uterus and bone. In addition to being able to induce endometrial hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma, it also appears able to induce endometriosis [7]. In contrast, other anti-oestrogen drugs (aromatase inhibitors) have been successfully used to treat endometriosis in postmenopausal women [8].

In our two benign cases of postmenopausal endometriosis, both women had initially been taking hormone replacement but had then stopped, presenting in one case 12 months later and in the other case 10 years later. The earlier presentation probably reflected initial suboptimal surgical treatment, whilst the later probably reflected de novo disease.

Although endometriosis is usually described as a benign condition, it is increasingly recognised as having malignant potential. The frequency of malignancy transformation has been reported as 0.7–1.0% [9]. Cancer can arise at any site of endometriosis, but most commonly occurs in the ovary. In one large longitudinal study, women with a history of ovarian endometriosis were four times more likely to develop ovarian cancer [10]. Clear-cell and endometrioid carcinomas are the commonest tumour types in the ovary, whilst clear cell adenocarcinoma and adenosarcoma appear to be the most common tumour types in extra-ovarian endometriosis [11]. Controversy exists regarding the exact mechanism of malignant transformation, but some have suggested a premalignant phase, characterised histologically by the presence of endometrial glands with cytological or architectural atypia. This has been referred to as atypical endometriosis [12]. In our two cases of malignancy, no atypical endometriosis appears to have been present. In the first case, the tumour was reported as a clear cell adenocarcinoma occurring in a patient who had previously had a pelvic clearance. The previous histology had confirmed endometriosis but did not suggest malignancy. In the second case, the patient presented 8 years after the menopause. The tumour appears to have arisen in the ovary before invading the serosal surface of the uterus to which it was adherent.

Clinically, patients with endometriosis-associated ovarian cancers have a better overall survival than those with ovarian cancer without endometriosis, presenting by and large at a less advanced stage and with lower-grade disease [13]. Sadly for one of our patients, this was not the case; the tumour was deemed inoperable, and she has been referred for radiotherapy.

In summary, postmenopausal endometriosis is a rare condition, and malignant transformation is even rarer. New genetic and molecular insights into its pathophysiology may in the future allow more accurate profiling of those patients who require radical treatment and those who can be managed conservatively. In the interim, clinicians and patients should be aware of the small risk of neoplastic change and be particularly aware of the malignant potential of endometriosis detected after the menopause.

References

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2000) Clinical green top guidelines: the investigation and management of endometriosis (24). http://www.rcog.org.uk/guidelines.asp?PageID=106&GuidelineID=10

Punnonen R, Klemi PJ, Nikkanen U (1980) Postmenopausal endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 11:195–200

Sampson JA (1927) Peritoneal endometriosis due to menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 14:422–469

Bellina JH, Schenck D (2000) Large postmenopausal ovarian endometrioma. Obstet Gynecol 96:846

Goumenou AG, Chow C, Taylor A, Magos A (2003) Endometriosis arising during estrogen and testosterone treatment 17 years after abdominal hysterectomy: a case report. Maturitas 46:239–241

Deval B, Rafii A, Dachez M, Kermanash R, Levardon M (2002) Sigmoid endometriosis in a postmenopausal woman. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187:1723–1725

Ismail SM, Maulok TG (1997) Tamoxifen-associated post-menopausal endometriosis. Histopathology 30:187–191

Bulun SE, Zeitoun KM, Takayama K, Noble L, Michael D, Simpson E, et al. (1998) Aromatase expression in endometriosis: biology and clinical perspectives. In: Lemay A, Maheux R (eds) Understanding and managing endometriosis. Advances in research and practice. Parthenon, Quebec City, pp 139–148

Vignali M, Infantino M, Matrone R, Chiodo I, Somigliana E, Busacca M, Vigano P (2002) Endometriosis: novel etiopathogenetic concepts and clinical perspectives. Fertil Steril 78:665–678

Brinton LA, Gridley G, Persson I, Baron J, Bergqvist A (1997) Cancer risk after a hospital discharge of endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecal 176:572–579

Varma R, Rollason T, Gupta J, Maher E (2004) Endometriosis and the neoplastic process. Reproduction 127:293–304

LaGrenade A, Silverberg SG (1988) Ovarian tumors associated with atypical endometriosis. Hum Pathol 19:1080–1084

Modesitt SC, Tortolero-Luna G, Robinson JB, Gershenon DM, Wolf JK (2002) Ovarian and extraovarian endometriosis-associated cancer. Obstet Gynecol 100:788–795

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Taylor, A.A., Kenny, N., Edmonds, S. et al. Postmenopausal endometriosis and malignant transformation of endometriosis: a case series. Gynecol Surg 2, 135–137 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10397-005-0096-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10397-005-0096-6