Abstract

Aim

The aim of the present study was to explore trends in NEET rates according to gender and NEET subgroups in young Italian people. Furthermore, it examined whether trends changed following specific time points such as financial crisis in 2008, education and labor market strategies, and the partial recovery of European economy in 2014.

Methods

All data were obtained from the ISTAT (Italian National Institute of Statistics) Database. NEET rates, stratified by gender and NEET subgroup, were extracted for young people aged 15 to 24 years from 2004 to 2019 in Italy. Trends in NEET rates stratified by gender and NEET subgroup (i.e., "unemployed", "potential workforce", "unavailable") were analyzed using joinpoint regression models.

Results

The trends of the unemployed NEET rate were stable or decreasing until 2008, increasing between 2008 and 2014 and thereafter decreasing across both male and female genders. The trends of potential workforce NEET rate sharply increased between 2004 and 2014, and afterwards decreased in both genders. Finally, the trends of unavailable NEET rate were stable in females and constantly increasing in males over the entire analyzed period.

Conclusions

According to the results of this ecological study, trends differences in NEET subgroups’ rates emerged. The financial crisis in 2008 and the education and labor market strategies around 2014 mainly coincided with relevant changes in trends of unemployed NEET rate and, partially, with changes in trends of potential workforce NEET rate. The trend in unavailable NEET rate increased over the entire period in males, and did not show important changes in either gender.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The acronym NEET stands for “Not in Education, Employment, or Training” and indicates the disengagement of young people from the process of entering adult life, the labour market, and the possibility of accessing it through education or training (Bynner and Parsons 2002). NEET youths are not engaged in the education system or part of the workforce at a specific point in time or for a period of time. The EU Labour Force Survey indicates the rate of young NEET as the proportion of young people neither in employment nor in education and training in the 4 weeks preceding the survey (Eurostat 2020a). Considering the Euro area, the proportion of young people aged 15–34 who were NEET in 2019 varied significantly across the 19 countries: from the low end of 6.9% in Luxembourg to 23.8% in Italy, with an overall mean of 14.1% in the Euro Area (Eurostat 2020b).

The ecological systems theory of development (Bronfenbrenner 1979) highlighted the primary role that contextual factors play in shaping the specific developmental pathway of individuals. Individual life courses develop within the broader socio-cultural context and historical period in which individuals grow up and in which important life events have occurred, such as the transition to adulthood and in the labour market. A precarious labour market and the increase in qualification levels make youths who drop out of school with low qualifications particularly vulnerable to NEET experience (Eurostat 2020a; Lorinc et al. 2019; Lunsing 2007).

Being not in education and unemployed typically has its roots in resource deficiencies during childhood, namely, disadvantaged family circumstances and values that do not give relevance to academic success (Nerli Ballati and Di Paola 2017; Bynner 1998). Later in life, adolescents who lack support facing the transition from school to work may be particularly at risk of social exclusion and becoming NEET (Bynner and Parsons 2002; Lorinc et al. 2019). Individual and familial characteristics seem to interact with socio-economic factors in delineating the risk of becoming NEET and the possibilities of entering the labour market (Caroleo et al. 2020; Egan et al. 2015; Lunsing 2007).

NEET youths’ subgroups

Previous studies showed that approximately 20–30% of NEET adolescents were NEET at 5–8 years follow-up (Bynner and Parsons 2002; Gutierrez-Garcia et al. 2017). However, the concept of NEET does not refer to a homogeneous group of people (Brunetti and Ferri 2018; Furlong 2006). A first distinction within the NEET group between “unemployed” and “Inactive” youths should be considered (Quintano et al. 2018). The term unemployed refers to young people who are looking for work but cannot find it, inactive youths are defined instead as (a) youths who declare themselves available to work, despite not having done an active job search, and youths who have carried out job search actions, but are not immediately available to work (i.e., Potential workforce NEET subgroup), and (b) youth who have not looked for work and are not available to work (i.e., Unavailable NEET subgroup).

The inactive NEET group includes people with different motivations for not working, such as young mothers who take care of their children, and young people who receive disability pensions or are unable to work. Therefore, the NEET group includes people with heterogeneous characteristics, experiences, and needs (Yates and Payne 2006). Providing support to the distinction of NEET in different subgroups, Furlong (2006) showed that in a large sample of young Scottish people the majority of NEETs were looking for a job, almost one in five females were caring for children or family, one in ten young were engaged in unspecified activities, a small proportion of NEET was sick or disabled, and a very small proportion were on unpaid holiday, taking a ‘gap’ year or undertaking voluntary work,. However, despite their different characteristics, NEET youths could share similar difficulties in moving from adolescence to adulthood and constitute a group at risk for negative consequences later in life, such as continuation of NEET status, unemployment, dissatisfaction and problems with life, and lack of a sense of control (Baggio et al. 2015; Bynner and Parsons 2002; Furlong 2006; Gutierrez-Garcia et al. 2017; Ralston et al. 2016).

In light of the above, the present study aimed at examining the trends in NEET youths aged 15–24 years, by gender and NEET subgroup in Italy from 2004 to 2019. Furthermore, this study observed if the rate of NEET Italian youths had varied due to the financial crisis of 2008 or if there was a pre-existing rising trend. At the same time, changes in the trends in NEET Italian youths’ rate possibly due to the effects of the implementation of education and labour market strategies in Italy and to the partial recovery of the European economy after the 2008 economic crisis (European Commission 2014a) were examined, considering trend changes in NEET rate after 2014. Some of the education and labour market strategies were the European financial resource to support the implementation of the structural reform “Youth Guarantee” (European Commission 2014b), the reforms of the labour work “Jobs Act” (Law 183/2014), and the education system “Buona Scuola” (Law 107/2015) in Italy.

Methods

Data source

Numbers and rate of NEET youths aged 15–24 years in Italy were examined. The annual NEET data were extracted in June 2020 from the ISTAT Database Giovani.Stat produced by the Italian National Institute of Statistics for the periods 2004–2019 and stratified by gender and NEET subgroup. Every year, the ISTAT collects information on a sample of over 250,000 families residing in Italy (for a total of about 600.000 people), distributed in around 1100 Italian municipalities. Families who habitually live abroad and permanent members of cohabitations (e.g., religious institutes, educational institutes, etc.) are excluded. The Giovani.Stat database provides population-level data for the following NEET subgroups: “unemployed” (i.e., young people who are looking for work but cannot find it), “potential workforce” (i.e., youths who declare themselves available to work despite not having done an active job search, and youths which have carried out job search actions but are not immediately available to work), and “unavailable” (i.e., youths who have not looked for work and are not available to work).

According to Italian law, the study was exempted from approval by an ethics committee because all the data used were deidentified and publicly available.

Statistical analysis

Crude rates of NEET youths were obtained from the Giovani.Stat database as the annual number of NEET per 100 young people in the corresponding age group (15–24 years), by gender and subgroups. Trends in NEET rate were analyzed using the Joinpoint Regression Program, version 4.8.0.1, from the US National Cancer Institute. The turning points of the examined time periods were determined by regression models separately by gender (Kim et al. 2000). These models were used to estimate the annual percent change (APC) in rate and the number and location of joinpoints, based on linear regression with the log NEET rate as the dependent variable and the year as the independent variable. The regression model assumed that the random errors followed a Poisson distribution, and the regression coefficients were estimated by weighted least squares (National Cancer Institute 2020). The Joinpoint Regression Program performs multiple tests in order to select the number of joinpoints using permutation test and choosing the best model. In the final model, joinpoints indicate changes in long-term trends. APC, based on the slope of the line segment, describe an increasing (positive APC value) or decreasing (negative APC value) trend. An important change of a trend occurred when the slope of the curve changed significantly, as indicated by p < .05.

Results

The average rate and rate range across the entire observation period are shown in Table 1, and the results of the joinpoint analyses for the overall NEET group and each subgroup, stratified by gender, are reported in Table 2.

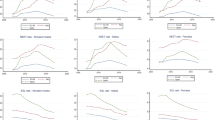

As shown in Fig. 1, two joinpoints were identified when analyzing the trend rate of the overall NEET group in males and females. The shape of the trends was partially similar across gender. The NEET rate in males was stable between 2004 and 2008. Afterwards, the rate sharply rose by 8.4% per year until 2013. Between 2013 and 2019, the rate decreased by 3.8% per year. The NEET rate in females decreased by 3.5% per year between 2004 and 2007. Afterwards, there was an increase of 3.8% per year until 2013. From 2013 to 2019 the rate decreased again by 2.6% per year.

Trends in unemployed NEET rates

Two joinpoints were detected for each gender, as depicted in Fig. 2. The shapes of the trends were similar across gender. Among males, there was a non-significant decreasing trend in unemployed NEET rate between 2004 and 2007. Among females, the decreasing trend by 12.9% per year during the same time period was significant. Afterwards, the curve sharply rose by 11.2% and 9.6% per year until 2014 among males and females, respectively. Thereafter, it sharply decreased by 8.5% and 7.2% per year until 2019 among males and females respectively.

Unemployed NEET trends among males and females aged 15–24 years in Italy, 2004–2019. Dots: male unemployed NEET rate; triangles: female unemployed NEET rate. The two bold vertical lines denote the time points when the financial crisis occurred (2008) and when education and labor market strategies were introduced (2014)

Trends in potential workforce NEET rates

As shown in Fig. 3, a joinpoint was found in both genders. In males, the potential workforce NEET rate rose between 2004 and 2012, afterwards the rate decreased until 2019 by 3.3% per year. In females, the potential workforce NEET rate increased between 2004 and 2014, then the rate decreased by 5.2% per year from 2014 to 2019.

Potential workforce NEET trends among males and females aged 15-24 years in Italy, 2004–2019. Dots: male potential workforce NEET rate; triangles: female potential workforce NEET rate. The two bold vertical lines denote the time points when the financial crisis occurred (2008) and when education and labor market strategies were introduced (2014)

Trends in unavailable NEET rates

As depicted in Fig. 4, Joinpoint analyses indicated no joinpoint for both males and females. In males, a significant increase in unavailable NEET rate of 2.3% per year was detected between 2004 and 2019. In females, the unavailable NEET rate remained stable across the entire period examined.

Unavailable NEET trends among males and females aged 15–24 years in Italy, 2004–2019. Dots: male unavailable NEET rate; triangles: female unavailable NEET rate. The two bold vertical lines denote the time points when the financial crisis occurred (2008) and when education and labor market strategies were introduced (2014)

Alternative analysis for the detection of changes in trends rates of NEET group and subgroups

As requested during the review process, alternative analyses testing for significant changes in trend rates of NEET were performed in order to check whether the results were “robust”. Firstly, the “segmented” Package in R (version 3.6.3) to replicate the results was used. Breakpoints were added until the model-fit did not increase substantially (i.e., < 5% based on the adjusted R2 values).

Findings of segmented regression displayed the same number of Joinpoint analysis breakpoints, and the most important changes of trends were comparable (except for breakpoints detected in trend rate of unavailable NEET females). The results of statistical analysis of NEET trends among young people aged 15–24 years using R are shown in the supplementary material. The only difference in the results of R and Joinpoint analysis concerns the breakpoints highlighted in trend rate of unavailable NEET females: the analysis conducted in R highlighted two breakpoints, while on the contrary, the analysis in Joinpoint found no breakpoint. This different result was probably due to data variability. Therefore, the main changes of the trends (i.e., change of direction upwards–downwards) were robust across the two different packages.

Secondly, significant trend changes in 2008 (i.e., financial crisis) and 2014 (i.e., implementation of education and labour market strategies in Italy, and partial recovery of the European economy after the 2008 economic crisis) were tested using the Chow test for structural break. The Chow test was carried out using SPSS’s General Linear Model procedure with an LMATRIX (contrast coefficients matrix) subcommand. Findings showed that in correspondence of 2008 and 2014, significant structural breaks in trend rate of NEET, and unemployed and potential workforce NEET subgroups, occurred (Table 3). No structural break in correspondence of 2008 and 2014 was detected in trend rate of unavailable NEET for either males or females. Importantly, Chow test results supported those obtained through the implementation of Joinpoint regression models.

Discussion

The trends analysis of the overall NEET rate in young people aged 15–24 in Italy showed a clear pattern consistent across genders. The NEET rate was stable or decreasing until 2007, it strongly rose between 2008 and 2014, and declined afterwards.

Considering NEET subgroups, to the extent of my knowledge this is the first study to analyse trends rates of unemployed, potential workforce, and unavailable NEET in Italy between 2004 and 2019. Trends in unemployed NEET rates were comparable to those of the overall NEET group: the rate decreased until 2007, thereafter rose between 2007 and 2014, and declined until 2019 in both males and females. However, study findings showed differences in trends of NEET rates by NEET subgroups. The trend rates of the potential workforce and unavailable NEET subgroups exhibited specific patterns. In particular, the potential workforce NEET rates constantly increased until 2012 in males and 2014 in females, and both decreased afterwards. The unavailable NEET rate remained stable for the female gender, while it showed a constant increase among the male gender over the entire period examined.

Findings of the present study indicated that the financial crisis of 2008 and the education and labour market strategies during 2014 coincided with changes in trends of NEET rate, mostly due to changes in the NEET rate of unemployed young people. These results are consistent with those of other studies that highlighted substantial increase in youth unemployment over the course of the financial crisis as well as initial decrease after 2014 (Choudhry et al. 2010; De Luca et al. 2019). The lower level of experience of young workers and their greater representation among temporary workers, who are generally more vulnerable to cyclicality and who have been disproportionately displaced from employment during the crisis, could explain the sharp rise in the unemployment rate (European Central Bank 2014).

The reduction in unemployed NEET rate after the increase due to the financial crisis could be related to the implementation of labour market strategies and contextually to the partial recovery of the economy after the 2008 economic crisis. For example, the Youth Guarantee plan aimed to increase the chance for young people to find a good-quality job suited to their education, skills, and experience, or to acquire the education, skills, and experience required to find a job in the future (e.g., through an apprenticeship, a traineeship, or continued education) (European Commission 2020). More than 20 million young people registered to the Youth Guarantee program during the period 2014–2019 in Europe, and the number of NEET has been reduced by 1.9 million (European Commission 2019). In particular, 1.6 million of young people took part in the program between 2014 and 2019 in Italy (ANPAL 2020). Eight hundred and seventy thousand active policy interventions were provided, of which 57% concerned extra-curricular internship, 26% concerned employment incentives, and 13% concerned a training course. Between 45% and 64% of young people who concluded the intervention were employed within 6 months after its conclusion (ANPAL 2020). However, this positive outcome was influenced by gender, age, and education (ISFOL 2016).

The financial crisis of 2008 did not coincide with changes in trends of the potential workforce and unavailable NEET rates, which had increased since 2004 (except for the rate of unavailable NEET in females). The rising trends in the potential workforce and in unavailable male NEET rates which started in 2004, and thus prior to the financial crisis occurred in 2008, seem to reflect the disengagement of young people from the process of entering adult life, the difficulties in facing the transition from the school system to the labour market, and the possibility of accessing it through education or training (Bynner and Parsons 2002; Eurostat 2020a; Lorinc et al. 2019; Lunsing 2007). On the other hand, changes in the potential workforce NEET rate were detected concomitantly to the introduction of the education and labour market strategies, despite the rate among males already showing a decrease since 2012.

Next, and most importantly, the implementation of education and labour market strategies did not coincide with changes in the unavailable NEET rate across both males and females. In addition, the unavailable NEET rate among young males increased over the entire period under examination. The financial crisis of 2008 as well as the education and labour market strategies and the partial recovery of European economy during 2014 coincided with no change in trend rates. A possible explanation for this finding could be linked to the fact that the labour market strategies may focus the attention on young people who can easily be moved into employment, education, or training activity, at the expense of other young who are in greater need due to other problems or risks and thus do not receive attention (Yates and Payne 2006). As suggested by De Luca et al. (2019), the high rate of inactive youth could indicate a lack of adequate services assisting disabled persons in finding employment. At the same time, it could be due to different propensity to work, low level of education, engagement in irregular or criminal economy, and discouragement (De Luca et al. 2019). Moreover, among the unavailable NEETs who have not looked for work and are not available to work there may be young people who socially isolate themselves for an extended period of time and are not interested in entering the labour market or in social relationships, the so-called “hikikomori” (Kato et al. 2019). The characteristics of NEET and hikikomori are very different, and only a small proportion of NEETs could be constituted by young people socially isolated for prolonged periods of time, partially corresponding to the “invisible” NEETs (Maguire 2015). However, NEET and hikikomori share a tendency to deviate from mainstream cultural attitudes and values that made them at risk of social exclusion and marginalization (Uchida and Norasakkunkit 2015). In the long term, the hikikomori phenomenon as well as the NEET one could represent a socio-economic problem for wealthy societies (Odoardi 2020; Varnum and Kwon 2016). Future studies should explore the heterogeneity and psychophysical well-being of individuals in the unavailable NEET subgroup.

Finally, the high but stable rate of unavailable NEET young females could reflect the inactivity related to being a mother or the inability to enter the labour market due to the need to take care of the children, as indicated by previous studies (Bynner and Parsons 2002; Furlong 2006). On the other hand, in some regions of Italy, especially in the South, informal employments are widespread, making good estimates difficult to reach (De Luca et al. 2019).

The present study highlighted the different trends in rates of NEET subgroups as well as the possible differential impact of education and labour market strategies on them. These results lead the focus on the need to investigate the factors associated to the membership to the NEET subgroups. Accordingly, public measures should be tailored to the specific needs and characteristics of each subgroup. Furthermore, considering that young NEETs are at risk for various negative consequences, due to the intertwining of individual, familial, and socio-economic variables, the results of the present study give rise to concern, given the constant increase of unavailable NEET rate among Italian young adult males. At the same time, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic will probably cause a socio-economic crisis and an additional increase in youth unemployment and NEETs (International Monetary Fund 2020; Mayhew and Anand 2020). The possibility of an increase in the rate of young NEETs and unemployment overall needs greater attention, since previous studies showed that the risk of poor mental health as well as suicide rate has increased during periods of socioeconomic recession, especially among youths (Chang et al. 2013; Madianos et al. 2014; Odone et al. 2018).

This study suffers some limitations. First, due to its ecological design, the data capture NEET only on the population level. Second, the time points set for the financial crisis (2008) and implementation of education and labour market strategy and the partial recovery of European economy (2014) did not necessarily coincide with the moment when their effects occurred, despite the analyses showing no trend changes after 2014. Furthermore, the design of the study did not allow for causal inferences. Finally, the present study did not explore the differences in trend rates across the Italian regions. In fact, the different levels of economic development between the Centre-North and the South of Italy are also reflected in the professional condition of young people and, specifically, in the different NEET rates, which are higher in the South (Mussida and Sciulli 2018; Quintano et al. 2018). However, the present study has important implications for understanding NEET in young Italian people, such as differences in trends according to NEET subgroups. Joinpoint regression models were applied to estimate the trends in young NEETs between 2004 and 2019, which involved the best fit of segmented lines connected at the turning points using a Poisson model of variation. This was the first utilization of Joinpoint regression to explore the trends of NEET rate in Italy.

More could be done to identify and better support young NEETs. Prolonged NEET status is inevitably linked to the lack of a genuine base for employability, given that disengagement from labour market, education, and training increase the lack of working experience and professional knowledge. A more detailed focus on NEET subgroups could guarantee the setting of tailored social support policies, taking into consideration the specific characteristics and needs of each subgroup (Furlong 2006; Lunsing 2007). This creates the need for investments in social, educational, and training infrastructures that will keep opportunities open (Bynner and Parsons 2002; Lorinc et al. 2019), guaranteeing attention to NEET mental health. In accordance with Maguire (2015), re-engagement strategies for the most isolated NEET groups should be implemented.

References

ANPAL (2020) Garanzia Giovani in Italia. Rapporto quadrimestrale n°3 / 2019. ANPAL, Trieste. https://www.anpal.gov.it/notizie-dati-e-indagini. Accessed 4 June 2020

Baggio S, Iglesias K, Deline S, Studer J, Henchoz Y, Mohler-Kuo M, Gmel G (2015) Not in education, employment, or training status among young Swiss men. Longitudinal associations with mental health and substance use. J Adolescent Health 56(2):238–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.006

Brunetti I, Ferri V (2018) Essere NEET in Italia: i principali fattori di rischio. Riv Ital Econ Demogr Stat LXXII(2):12

Bronfenbrenner U (1979) The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Bynner J (1998) Education and family components of identity in the transition from school to work. Int J Behav Dev 22(1):29–53

Bynner J, Parsons S (2002) Social exclusion and the transition from school to work: the case of young people not in education, employment, or training (NEET). J Vocat Behav 60(2):289–309. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1868

Caroleo FE, Rocca A, Mazzocchi P, Quintano C (2020) Being NEET in Europe before and after the economic crisis: an analysis of the micro and macro determinants. Soc Indic Res 149(3):991–1024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02270-6

Chang S-S, Stuckler D, Yip P, Gunnell D (2013) Impact of 2008 global economic crisis on suicide: time trend study in 54 countries. BMJ 347:f5239

Choudhry MT, Marelli E, Signorelli M (2010) The impact of financial crises on youth unemployment rate. Quaderni del Dipartimento di Economia 79/2010. Università di Perugia, Dipartimento Economia, Perugia, Italy

De Luca G, Mazzocchi P, Quintano C, Rocca A (2019) Italian NEETs in 2005–2016: have the recent labour market reforms produced any effect? CESifo Econ Stud 65(2):154–176. https://doi.org/10.1093/cesifo/ifz004

Egan M, Daly M, Delaney L (2015) Childhood psychological distress and youth unemployment: evidence from two British cohort studies. Soc Sci Med 124:11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.023

European Central Bank (2014) The impact of the economic crisis on Euro area labour markets. Monthly Bulletin, October 2014. European Central Bank, Frankfurt

European Commission (2014a) European Economic Forecast European Economy — Winter 2014. Economic and Financial Affairs. European Commission, Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/european_economy/2014/ee2_en.htm. Accessed 4 June 2020

European Commission (2014b) The EU Youth Guarantee. European Commission, Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_14_571. Accessed 4 June 2020

European Commission (2019) Youth Guarantee & Youth Employment Initiative. European Commission, Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?pager.offset=0&catId=1036&langId=en&moreDocuments=yes. Accessed 4 June 2020

European Commission (2020) Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion. The Youth Guarantee country by country — Italy. European Commission, Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1161&langId=en&intPageId=3340. Accessed 4 June 2020

Eurostat (2020a). Statistics on young people neither in employment nor in education or training. Eurostat, Luxembourg. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Statistics_on_young_people_neither_in_employment_nor_in_education_or_training#The_transition_from_education_to_work. Accessed 4 June 2020

Eurostat (2020b) Young people neither in employment nor in education and training by sex, age and labour status (NEET rates) (Last update: 21-04-2020). Eurostat, Luxembourg. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/products-datasets/-/EDAT_LFSE_20. Accessed 4 June 2020

Furlong A (2006) Not a very NEET solution: representing problematic labour market transitions among early school-leavers. Work Employ Soc 20(3):553–569. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017006067001

Gutiérrez-García RA, Benjet C, Borges G, Méndez Ríos E, Medina-Mora ME (2017) NEET adolescents grown up: eight-year longitudinal follow-up of education, employment and mental health from adolescence to early adulthood in Mexico City. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 26(12):1459–1469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1004-0

International Monetary Fund (2020) Global Financial Stability Report. Markets in the time of COVID-19. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

ISFOL (2016) Rapporto sulla Garanzia Giovani in Italia. Maggio. ISFOL, Rome. https://www.isfol.it/isfol-europa/garanzia-giovani. Accessed 8 June 2020

Kato TA, Kanba S, Teo AR (2019) Hikikomori: multidimensional understanding, assessment and future international perspectives. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 73(8):427–440

Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN (2000) Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 19(3):335–351. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::AID-SIM336>3.0.CO;2-Z

to hereLőrinc M, Ryan L, D’Angelo A, Kaye N (2019) De-individualising the ‘NEET problem’: an ecological systems analysis. Eur Educ Res J. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904119880402

Lunsing W (2007) The creation of the social category of NEET (not in education, employment or training): do NEET need this? Soc Sci Jpn J 10(1):105–110. https://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/jym016

Madianos MG, Alexiou T, Patelakis A, Economou M (2014) Suicide, unemployment and other socioeconomic factors: evidence from the economic crisis in Greece. Eur J Psychiat 28(1):39–49

Maguire S (2015) NEET, unemployed, inactive or unknown — why does it matter? Educ Res 57(2):121–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2015.1030850

Mayhew K, Anand P (2020) COVID-19 and the UK labour market. Oxford Rev Econ Policy 36(Suppl_1):S215–S224. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/graa017

Mussida C, Sciulli D (2018) Labour market transitions in Italy: the case of the NEET. In: Malo MÁ, Moreno Mínguez A (eds) European youth labour markets. Springer, Cham, pp 125–142

(2020) Surveillance Research Program: Joinpoint Help System. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/help/joinpoint. Accessed 5 June 2020

Nerli Ballati E, Di Paola P (2017) I NEET in Italia, una questione generazionale o di classe? Fondazione Ermanno Gorrieri, Modena. www.eticaeconomia.it/i-NEET-in-italia-una-questione-generazionale-o-di-classe/. Accessed 4 June 2020

Odoardi I (2020) Can parents’ education lay the foundation for reducing the inactivity of young people? A regional analysis of Italian NEETs. Econ Polit 37(1):307–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-019-00162-8

Odone A, Landriscina T, Amerio A, Costa G (2018) The impact of the current economic crisis on mental health in Italy: evidence from two representative national surveys. Eur J Pub Health 28(3):490–495. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckx220

Quintano C, Mazzocchi P, Rocca A (2018) The determinants of Italian NEETs and the effects of the economic crisis. Genus 74(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-018-0031-0

Ralston K, Feng Z, Everington D, Dibben C (2016) Do young people not in education, employment or training experience long-term occupational scarring? A longitudinal analysis over 20 years of follow-up. Contemp Soc Sci 11(2-3):203–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2016.1194452

Uchida Y, Norasakkunkit V (2015) The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: assessing the risks and consequences of becoming culturally marginalized. Front Psychol 6:1117. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01117

Varnum MEW, Kwon JY (2016) The ecology of withdrawal. Commentary: the NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: assessing the risks and consequences of becoming culturally marginalized. Front Psychol 7:764. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00764

Yates S, Payne M (2006) Not so NEET? A critique of the use of ‘NEET’ in setting targets for interventions with young people. J Youth Stud 9(3):329–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260600805671

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

SA is supported by the International Post-degree Scholarship of the Sapienza, University of Rome. The sponsor had no influence on the conduct of this study.

Informed consent

This study does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 228 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Amendola, S. Trends in rates of NEET (not in education, employment, or training) subgroups among youth aged 15 to 24 in Italy, 2004 - 2019. J Public Health (Berl.) 30, 2221–2229 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01484-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01484-3