Abstract

Background

Literature on self-management innovations has studied their characteristics and position in healthcare systems. However, less attention has been paid to factors that contribute to successful implementation. This paper aims to answer the question: which factors play a role in a successful implementation of self-management health innovations?

Methods

We conducted a narrative review of academic literature to explore factors related to successful implementation of self-management health innovations. We further investigated the factors in a qualitative multiple case study to analyse their role in implementation success. Data were collected from nine self-management health projects in the Netherlands.

Results

Nine factors were found in the literature that foster the implementation of self-management health innovations: 1) involvement of end-users, 2) involvement of local and business partners, 3) involvement of stakeholders within the larger system, 4) tailoring of the innovation, 5) utilisation of multiple disciplines, 6) feedback on effectiveness, 7) availability of a feasible business model, 8) adaption to organisational changes, and 9) anticipation of changes required in the healthcare system. In the case studies, on average six of these factors could be identified. Three projects achieved a successful implementation of a self-management health innovation, but only in one case were all factors present.

Conclusions

For successful implementation of self-management health innovation projects, the factors identified in the literature are neither necessary nor sufficient. Therefore, it might be insightful to study how successful implementation works instead of solely focusing on the factors that could be helpful in this process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The increase in the number of chronically-ill patients and rising healthcare costs make it necessary to achieve a balance between the demand for care and the capacity to provide it (Bodenheimer et al. 2002; Lorig and Holman 2003; Janssen and Moors 2013). Innovations in healthcare are urgently needed, and much is expected from self-management innovations (Bodenheimer et al. 2002; Lorig and Holman 2003; Jonkman et al. 2016). Self-management health innovations aim to equip patients with skills to function optimally, for example by providing monitoring or treatment tools through smartphone or e-health applications (Jonkman et al. 2016). The advantage of self-management is that fewer visits to medical professionals are needed (Adepoju et al. 2014; Ahn et al. 2015), the number of unexpected hospital admissions decreases (Brady et al. 2013; Zwerink et al. 2014), and better therapy compliance is achieved (Denford et al. 2013), which ultimately leads to improved health outcomes and reduced healthcare costs.

Against this background, it is not surprising that research has paid increasing attention to the development of self-management health innovations (Barlow et al. 2000; Hendy et al. 2012). Part of this research has focused on the characteristics of self-management in healthcare, and tried to better understand what self-management in health can achieve. Lorig and Holman (2003) studied patient characteristics that could lead to more efficacious use of self-management tools. They proposed six self-management skills that patients need to develop: problem solving, decision making, resource utilisation, formation of a patient–provider partnership, action planning, and self-tailoring. They emphasised a possible mechanism, self-efficacy, through which self-management health innovations work for patients. Ryan and Sawin (2009) reported three patient-related factors for self-management in healthcare to work: enhancing knowledge and beliefs, regulation of skills and abilities, and social facilitation. A third body of literature has looked at factors required to organise self-management at the level of healthcare organisations and of the healthcare system. An example is the Chronic Care Model for improving the care of the chronically ill, developed by Wagner et al. (1996). They define six factors: health system, decision support, self-management support, community resources, delivery system design, and clinical information systems. Grey et al. (2006) focused on self and family management, but next to (for example) individual factors they also include the system level. So, there is a wide range of self-management health models presented which include factors ranging from patient to system characteristics as well as the changes needed in healthcare. However, the implementation processes of self-management health innovations and the factors that enhance such processes have received considerably less attention in these models. We know much less about the implementation of self-management health innovations into routine practice or organisations (Gray et al. 2011; Macdonald et al. 2008). We define implementation as the actual use or integration of an innovation within a specific setting in an organisation (Rabin et al. 2008.

The aim of this paper is to explore which factors contribute to successful implementation of self-management health innovations. The brief review above conveyed that there has not been a full-fledged conceptual model presented in literature that can explain implementation success. Therefore, we were first interested in capturing individual factors that have been investigated across a wide range of disciplines. Relevant to implementation we aimed to cover: 1) processes of utilising knowledge of research projects and of transferring knowledge from research to practice, 2) the innovation and development processes of self-management health products and services, and 3) the adoption process of patients and healthcare providers. To cover these three elements, we reviewed academic literature in the fields of: 1) research impact, 2) innovation sciences, and 3) marketing and collected factors that explain implementation of self-management health innovations. This overview of factors collected across several disciplines results in a conceptual model. We then explored to what extent this model helped in explaining implementation success by applying it in a qualitative multiple case study. In the end, we aim to answer the following research question: which factors play a role in a successful implementation of self-management health innovations?

The remaining part of this paper proceeds as follows: the following section presents a narrative review of the research impact, innovation sciences and marketing literature. This narrative review results in a conceptual model that we used as input for the qualitative multiple case study. The Method section explains the methodology of the qualitative multiple case study. The Results section provides the results and analysis of this qualitative multiple case study; this is followed by the conclusion section and a discussion section which reflects on the findings and discusses limitations and directions for future directions.

Narrative review of literature on self-management health innovations

We conducted a narrative review of academic research impact, innovation science, and marketing literature (Green et al. 2006) to explore factors related to the implementation of self-management health innovations. Narrative reviews of the academic literature are focused on showing a broad perspective on a topic, and are used to link together many studies for the purpose of either reinterpretation or to find a connection (Green et al. 2006). We followed the established protocol for conducting narrative reviews as developed by Green et al. (2006). A multi-disciplinary expert team of innovation sciences (X, X), research impact (X), and marketing (X) experts was formed to represent the scientific disciplines. The identification of specific publications was part of the interdependent research process conducted on a consensus basis by the expert team.

Selection of papers for the narrative review

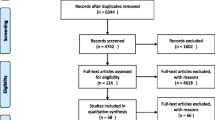

The selection of papers was completed in four steps (I–IV, Fig. 1).

Step I: Selection of journals.

The expert team was asked to propose a number of relevant journals in their field. The number of marketing journals (n = 19) was higher than the number of innovation sciences (n = 9) and research impact journals (n = 6). The marketing experts expected to find none to a few papers on self-management health innovations in the key journals in their field, which meant that they wanted to increase the number of journals to possibly find relevant papers in less well-known journals. The experts agreed on the final journal selection in a collaborative meeting. At the end of Step I, we had formed a collection of 34 journals (see Supplementary Table 1 and 2, Additional file 1).

Step II: Search process.

The journals were searched using the Scopus bibliographic database by applying a keyword search on the title, abstract, and keywords of the papers (Fig. 1, Step II). We used the broader keyword “health” instead of “self-management” because we also wanted to include publications about self-management innovations that do not use the word explicitly. Greenhalgh et al. (2004) inspired us by selecting words for the implementation of healthcare innovations. We used a broader selection than “implementation”, because we assumed that different terms are used to describe the process steps related to implementation. The experts agreed on the keyword selection in a collaborative meeting.

The search led to a selection of 654 sources.

Step III: First round selection and appraisal of documents.

Our goal was to identify publications that made a contribution, either conceptually or empirically, to the understanding of the implementation of self-management health innovations. Studies were screened on title/abstract by one researcher (X) to select possible relevant publications of the implementation of self-management health innovations. Taking the 654 publications resulting from Step II, we screened the documents and excluded non-relevant primary studies that did not pay attention to self-management innovations, and reviews that did not describe their methods. At this scoping stage, we used a broad interpretation of the operational definition of self-management innovations. We applied the definition proffered by Jonkman et al. (2016, p. 35): “self-management health innovations are interventions that aim to equip patients with skills to function optimally through at least two of the following aspects: 1) providing knowledge about the condition and/or treatment; 2) active stimulation of symptom monitoring; 3) enhancing problem solving skills (self-treatment, resource utilisation, stress/symptom management); 4) enhancing physical activity; 5) enhancing dietary intake; 6) enhancing smoking cessation; and 7) enhancing medication adherence.” This definition is about self-management health innovations across multiple chronic conditions. As a validation step in an expert meeting, the experts of each of the three scientific disciplines judged randomly selected abstracts on the criteria of Jonkman et al. (2016) and discussed the outcome together with the main researcher. These discussions supported the main researcher in refining the selection of the 654 abstracts. At the end of Step III, we produced a list of 217 sources. Full texts were retrieved for these sources.

Step IV: Second round selection and appraisal of documents.

The full texts were assessed by the main researcher (X) again using the definition of self-management of Jonkman et al. (2016); the innovation should contain at least two of the seven aspects mentioned in the definition. The papers were then evaluated on whether the phenomenon under study concerned an innovation. For this we used the following definition by Moors (2013, p. 7): ‘innovation is the successful development and application of knowledge and technology in the form of new technologies, products, processes, practices and services’. At the end of the process, we produced a list of 26 sources of which four were literature reviews. In an expert meeting, the participants discussed and validated the outcomes.

Analysis of the 26 publications

Analysis initially consisted of close reading, after which we used open coding in the second reading of the documents using ATLAS-ti software version 8.4.15. Based on this initial inductive coding, we developed a general framework of categories for selective coding in a third step, deductive reading of data, in the coding process known as ‘abduction’, to view further detail in our data (Tavory and Timmermans 2014). For consistency in coding, one other researcher coded randomly selected factors to the final categories (see Supplementary Table 3, Additional file 2). The two researchers discussed coding in an iterative exercise. No significant inconsistencies emerged. The final categories formed the basis for the conceptual model we used to explore factors that contribute to successful implementation of self-management innovations (see Table 1).

Factors contributing to implementation self-management

On the basis of analysing the 22 primary studies and the four systematic reviews, we developed a conceptual model (Table 1) with nine factors for the implementation of self-management health innovations: 1) iInvolvement of end-users, 2) involvement of local and business partners, 3) involvement of stakeholders within the larger system, 4) iailoring of the innovation, 5) utilisation of multiple disciplines, 6) feedback on effectiveness, 7) aavailability of a feasible business model, 8) adaption to organisational changes, and 9) anticipation of changes required in the healthcare system. We found that the factors are related to two dimensions: contexts of application and aspects of the implementation process. The focus is on both contexts and aspects, because we found that factors could be related to different contexts, such as different types of actors, i.e., end-users, the organisations or the healthcare system, and to different aspects, i.e., involvement, development and use. The conceptual framework in Table 1 presents the factors emerging from the review.

We now elaborate on the factors for the different aspects (involvement, development, use context) and discuss the various contexts (user, organisation, system) for each aspect.

Involvement

The involvement of end-users, local and/or business partner organisations, and stakeholders in the wider system (e.g., the government or healthcare insurance companies) is seen as important for implementation success of self-management healthcare innovations. Involvement of end-users is about the key role of end-users in transferring and propagating tactical data and tacit knowledge about their own situation and experience with an innovation (Papa et al. 2018). Their experiential and creative input can help developers in designing their innovations. An iterative and user-centred approach will also help to align with the norms and values of the users (Greenhalgh et al. 2018). The involvement of local and/or business partners is about the support from organisations both inside and outside the healthcare system. Papa et al. (2018) indicate that strategic, knowledge-driven partnerships amongst firms in the healthcare industry and with lead users are an important factor for the success of an innovation. Finally, an important factor in the system context is the involvement of stakeholders within the larger system, such as the national and local government healthcare insurance organisations and subsidy providers during the entire innovation process starting at the design or concept phase. Key stakeholders must understand why a self-management innovation is important, why the process of development and implementation needs explicit attention, and what the benefits are for them and for the system. When stakeholders articulate their values, motives, capabilities, and beliefs during the development of an innovation, the innovation better fits to the stakeholders’ context. If the innovation better fits to their interests, it is more likely that implementation success will be achieved (Greenhalgh et al. 2018).

Development

Self-management innovations undergo continuous development and tailoring during self-management health innovation projects. Tailoring of the innovation is about how an innovation, and also the messages and information about the technology or product, should be modified to suit each individual patient (Nakrem et al. 2018). The extent to which patients value features of a product may differ per patient. For example, some patients do not want their tool to be visible because it is stigmatising or uncomfortable, while others do not mind as long as it helps them to manage their days. For the adoption and implementation by individuals, the innovation should be tailored to ensure it will fit user practices and individual approaches to self-management (Sanders et al. 2012). The development and implementation of self-management health innovations requires the utilisation of multiple disciplines such as healthcare professionals, designers, technicians, management, technical, financial, and legal staff (Shulman et al. 2016). To ensure collaboration in the team, involved mediation is needed between disciplinary backgrounds and resources devoted to project conception, design and planning, implementation, and operation to create a shared vision within the team (Barlow et al. 2006). It will help if healthcare professionals and the technical team are co-located, so that the technical issues can be resolved in an ongoing manner (Greenhalgh et al. 2018). Finally, development of innovations in the healthcare domain goes together with feedback on effectiveness. This especially holds for developers who choose to follow a marketing path aimed at inclusion of the innovation in public healthcare schemes and reimbursement by health insurers. Inclusion in these coverage schemes requires evidence about (cost-)effectiveness. However, strict and standardised assessments might result in innovations that are unattractive. Standardised elements of trials, such as a participant recruitment process, are perceived as problematic for local implementation processes. In one study, local managers felt that the evaluation required a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach. The focus of the approach should meet the research goals instead of trying to understand the needs of the local healthcare organisation. Remote care made sense for local organisations and could be further scaled-up and sustained if there is a “one size fits all” approach (Peine and Moors 2015). Adequate human, financial, technological, and tangible resources are helpful for the evaluation of tailored self-management innovations, whereby new methods to measure the effectiveness and assess impact are required.

Use

A third main issue for the implementation of self-management innovations is the use aspect. Availability of a feasible business model is related to the context of the end-users. In many self-management health innovation projects, end-users are seen as customers who are responsible for their healthcare management, including making a choice for supporting resources and paying or managing the costs. Healthcare entrepreneurs are dependent on the characteristics and preferences of patients, the influences of family and friends and their interest in healthcare, and the patients having knowledge of the benefits of the innovation. The implementation of an innovation requires an adaption to organisational changes, because self-management health innovations need to be incorporated into routines of patients, healthcare professionals, relatives, and treatment programmes. Moreover, these innovations (mostly technologies) rely on human relationships across different disciplines (Shaw et al. 2017). A new organisational way of working is thus needed, in which responsibility for embracing the new technology is shared and not left to individual healthcare professionals and their patients (Nakrem et al. 2018). Professional practice is in the first place oriented at delivering personalised care instead of implementing a technology (Shaw et al. 2017). In addition to changes required in the healthcare organisation, often change is needed in the way the care around individual patients is organised by family, friends, and informal caregivers. For the implementation of many self-management health innovations, the assumption is made that there is a group of relatives and/or friends, who live close to the patient, are able to help with technological solutions, and are willing to collaborate on the care of the patient (Greenhalgh et al. 2018). Introducing technology in those cases instead of empowering patients, for instance, could make the patient even more dependent on informal care (Shaw et al. 2017). This is one of the reasons why it is important that the patient and his/her immediate social networks are given the opportunity to become familiar with the innovation before it is actually needed (Peine and Moors 2015). Often patients are not able to manage their care without help from others, and time is needed to incorporate the innovation into the routines of the patient as well. Finally, an important factor in the system context is the anticipation of changes required in the healthcare system. The implementation of self-management health innovations often requires policy changes, which raise financial, legal, and political challenges. Self-management innovations have been widely touted as methods for reducing costs in healthcare delivery. However, the costs of the required changes for implementing a self-management health innovation in the healthcare system, such as the preparation and management of policy documents and the adaption of regulations, also requires a lot of money and effort (Walters et al. 2012). The question of whether self-management health innovations would actually cost less is not easy to answer because of potential ongoing tailoring, the additional support needed in healthcare delivery, and upscaling issues related to the personalisation of the health innovation. Anticipated reduction in costs from reducing admissions is often not realised because of the complexities of reimbursement mechanisms, and because case management is often not ready for complete avoidance of admissions to hospitals or care homes (Greenhalgh et al. 2018). Next to the challenges, pressure from national and local authorities could heavily influence how healthcare professionals perceive the need for new technology (Hendy et al. 2012).

The narrative review yielded insights into the success factors related to the implementation of self-management health innovations. The next sections describe the case study, with the aim of exploring the above-identified factors in actual self-management health innovation projects.

Method

Based on the conceptual model as developed in the previous section we explored the successful implementation of self-management health innovations in a qualitative multiple case study (Stake 1995; Yin 2009), based on semi-structured interviews and document analysis.

Case selection

For this multiple case study, we selected nine research projects from the HU University of Applied Sciences in Utrecht (see Table 2). Dutch Universities of Applied Sciences (UASs) aim for research that directly contributes to practice, is scientifically rigorous, and is ethically responsible (Pijlman et al. 2017). We define practice-based research at UASs as a co-creation process in which the implementation of results into practice are realised from the integration of research results during the whole process through activities, interventions, and interactions with stakeholders (McColl-Kennedy et al. 2012). As implementation is an integral part of practice-based research, studying cases from UASs is interesting in relation to the process of successful implementation of self-management health innovations. We focused on one university of applied sciences because this ensured that the institutional embedding of the research projects remained more or less the same. Regional embedding and close connections with business and organisations is important to UASs, because through these connections they can contribute to regional development by building regional coalitions and linkages (Jongbloed 2010). Cases were selected from the project databases of subsidy providers and the website of the UAS under study. Descriptions of all projects found were assessed by one researcher to determine if the project was about self-management according to the definition by Jonkman et al. (Jonkman et al. 2016); see Fig. 1, Step III). The case selection was validated through discussion amongst the expert group and the main researcher.

Implementation success

When measuring implementation success we define implementation as the actual use or integration of an innovation within a specific setting in an organisation (Rabin et al. 2008). Implementation success in this study meets at least one of the following criteria: (1) the innovation is used in a specific programme of at least one organisation by the end-users themselves, (2) the innovation is integrated in daily routines of end-users in a specific setting in or related to an organisation, (3) the innovation brought on the market through a (healthcare) entrepreneur or publisher, or (4) the innovation is made available in an organisation whereby the actual use is monitored by the organisation as well.

Data collection

For the document analysis, we analysed documents from the project website or the public website of the UAS — such as timelines, activities, presentations, publications, news articles, and reports — to gain insights in the reported outcomes and activities that led to these outcomes. The semi-structured interviews were conducted with the main researchers (PhD students or project leaders) involved in the project of the selected self-management projects at UASs (n = 9), healthcare entrepreneurs (n = 3) and healthcare professionals (n = 4), as well as other researchers with another expertise (co-design and information systems) than the main researcher on the project (n = 2). In addition, we used six evaluation interviews conducted after the project with healthcare professionals of one of the projects. Semi-structured interviews offered the best opportunity to contribute to an understanding of the interaction of researchers with their context for innovation (Yin 1994). Interviewees were asked to describe how the project had evolved. A topic list based on the factors found in the narrative review of literature (Table 1) was used to provide structure to the interviews. This list consists of items regarding the success factors of and barriers to implementation. Interviewees were encouraged to be specific and to provide examples, but the semi-structured nature of the interviews allowed also for exploring additional issues.

Data analysis

Data analysis was done in two steps: 1) a detailed qualitative within-case analysis, and 2) a cross-case analysis (Stake 1995). Data analysis followed an abductive approach (Tavory and Timmermans 2014), meaning that we coded the documents and transcripts both inductively (starting with empirical data) and deductively (constantly comparing preliminary results to the conceptual model resulting from the overview of literature). The documents and interview transcripts were read and the content was highlighted using ATLAS-ti software version 8.4.15. Coding was done by the main researcher. The second step of the analysis was clustering all relevant data in the form of quotes from both interviews and documents. For each case, we analysed the presence of the selected success factors of the implementation of self-management health innovations, and structured them per project in separate tables (See Table 5.1–5.9, Additional file 4). We then conducted a cross-case analysis and clustered all relevant data in a data matrix, with the aim of exploring to what extent the factors found in the literature are able to explain implementation success over different cases. Our analysis was recursive, constantly moving from the specific cases to the more general, with the aim of identifying similarities and patterns across the variety of cases. In addition, we discussed the initial results in five meetings with the team of experts in innovation science (1, 2), marketing (3, 4) and research impact (5). The variety of data collection methods, and the combined and iterative methods of data analysis, made it possible to produce both situational and theoretically generalisable findings on success factors.

Results

The aim of this paper is to explore which factors contribute to a successful implementation of self-management health innovations. This section presents the findings of the qualitative multiple case study. The first part describes whether the studied self-management health projects were successful in terms of implementation. The second part provides the insights, based on the within-case analysis, into the factors according to the conceptual model: focusing on the involvement context, development context, and use context. The third part is based on the cross-case analysis, and describes to what extent the factors have led to a successful implementation of self-management health innovations in the cases.

Implementation success

We define implementation as the actual use or integration of an innovation within a specific setting in an organisation (Rabin et al. 2008). Three projects (projects 1, 2, and 3) achieved a successful implementation of a self-management health innovation. Table 3 presents the nine projects, and shows which projects reach a successful implementation at the moment of data collection related to the implementation criteria as mentioned in the method section. The developed intervention tool in project 1 is used and integrated in one of the partner organisations and in one non-organisation. The developed app in project 2 is integrated in the existing online system of an organisation with locations throughout the country. The talking tool in project 3 is marketed by a publisher and purchased by partner organisations that became enthusiastic during the project. The other six projects have not yet succeeded in implementing their innovation at the moment of data collection. In four of the projects (4, 5, 8, and 9) which have not reached a successful implementation yet, one or more project members are still active and able to implement the self-management health innovation.

The within-case analysis in the next section discusses identified factors that foster the implementation of self-management health innovations.

Identified factors

Based on the within-case analysis, we discuss the factors according to the conceptual model: focusing on the involvement context, development context and use context.

Factors related to involvement

The following factors are related to involvement: involvement of end-users, involvement of local and business partners, and involvement of stakeholders within the larger system. All nine projects involved end-users during a part of the research project.

The extent to which the researchers applied the involvement of end-users varies. One of the projects (project 3) used co-design for the functionality and user-friendliness of the tool. Other projects included an iterative co-creation process with evaluation cycles with involved end-users (projects 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9), but in these research projects the involvement was limited too. This has been illustrated in the following quote: “The most important choices were made in co-creation, but of course you also have choices in the clustering of the data. Clustering was done by the project team. It would have been useful if we also had patients and practitioners in that phase, but that would delay the process too much. So it was primarily a practical consideration” (researcher Project 1). At the same time, healthcare professionals emphasise the importance of involving the professional field: “What you often see is that healthcare entrepreneurs or entrepreneurs from other areas introduce health innovations because they think that they know how to innovate the healthcare sector. However, 90% of the innovations in healthcare are not implemented. If you want to make innovations usable for the healthcare practice, then the question for the innovation must come from the professional field and then the professional field must also be able to say what works and what does not work. The innovation and the new way of working are then accepted much more easily, because they are more compatible with the needs of the patients and caregivers. It’s okay if the process takes a little longer because the innovation is developed in a research project with the involvement of a UAS” (healthcare professional, project 5). The quote shows the importance of research in co-creation.

In all cases, the researchers worked together with different partners, but not especially with local or regional partners. In eight projects, a business partner was involved in reaching a realistic idea about the development of a final product, with the aim to implement and possibly scale up the innovation: “During the project we found it important for the continuation of the app after the implementation, to find a manager for the web portal” (researcher, project 2). The involvement of a business partner at the beginning of the project is not a guarantee for a successful collaboration at the end (projects 5 and 6), but it is still helpful to get insights to the possibilities and impossibilities. In addition, the business partner could also have a slightly different priority: “The tool is now far too expensive for the market. Our business partner indicated that if you produce small quantities, the product becomes more expensive. That makes sense, but it has become twice as expensive as estimated. That also has to do with the fact that our partner wants to make beautiful things. It looks nice, but it would not have mattered to me if it had worked, but not looked as nice.” In project 2, the business partner is owner of a franchise company in which the innovation is implemented: “We introduced the app to the market place, so we ensured that other physical therapy practices can also use it. They are actually the customers. And we also ensure that the app is available at all our own locations and can be used” (business partner, project 2). This quote shows that the involvement of a partner with a major network will help to implement the self-management health innovation, and will ensure that there is a continuation of the development of the tool.

Six out of nine projects involved stakeholders such as patient associations. For researchers, it was difficult to involve a healthcare insurance partner. Five of the researchers tried to involve healthcare insurance organisations in the beginning of the project, without success: “Involving healthcare insurance organisations was the most difficult. They actually said that we first had to come up with results and when the results were positive, they wanted to talk further” (project 2). Two of the involved business partners (projects 2 and 8) and one of the healthcare partners (project 5) did have contact with one or more healthcare insurance partners. The business partner in project 2 said: “With regard to the implementation of tools there are several barriers to the process, for instance the payment for an online consult, and we discussed those barriers with the healthcare insurance partners. We are constantly discussing these kinds of themes with them”. For researchers it seems more difficult to achieve a relationship with healthcare insurance organisations during a research project than with other stakeholders.

Factors related to development

The following factors are related to the development of self-management health innovations: tailoring of the innovation, utilisation of multiple disciplines, and feedback on effectiveness.

In five of the studied projects, tailoring of the innovation was seen as an important factor. One of the researchers indicated: “What I read in most studies about self-management health innovations is that the authors choose a one-size-fits-all intervention. That simply does not work. There is of course a general working principle behind self-management health innovations, but every person is different and it is difficult to determine what works for whom. Therefore we basically assume an intervention is tailored to the person” (researcher, project 9). However, two of the three projects which succeeded in implementation and upscaling did not have tailoring options in their innovation.

In all nine projects, partners with different disciplinary backgrounds worked together. Seven of the nine projects worked in multi-disciplinary research teams (projects 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8). According to the researchers, it is useful to work together in a multi-disciplinary team, although it is a difficult process and there are specific methods such as co-design needed to bring different disciplines together: “The co-design way was useful to combine different insights (...), the research traditions are so different. You must make explicit how you meet: the medical way or the non-medical way?” (researcher, project 1). Besides, working in multi-disciplinary research teams can make it more difficult to publish the results: “We have not published our research results yet, but I am concerned about that. That we are going to be criticised on a number of issues. For example, the co-design way of working, how are we going to write it down in a way that people benefit from it?” (researcher, project 3).

All nine projects evaluated the innovation during the co-creation process through different research activities, with or without users: “It is always an iterative process. There are multiple versions needed before you can actually start using a self-management health innovation” (researcher, project 9). Although an evaluation process does not automatically lead to a successful implementation, as in project 7: “We thought about it well, but we just see no effect at all. In the upcoming co-design session with all partners we will discuss how we will proceed.” For partners, the evaluation part of the project is also helpful in the implementation process of the self-management health innovations: “Scientifically substantiating the interventions is something I have always wanted. Through this collaboration, we can offer the app as more substantiated” (partner, project 2). All projects developed the innovation with evaluation cycles.

Factors related to use

The implementation of a self-management health innovation requires the use of the innovation on the level of its users, the involved (healthcare) organisations, and the healthcare system. The following factors are related to use: availability of a feasible business model, adaption to organisational changes, and anticipation of changes required in the healthcare system.

Four of the nine projects developed a business plan. Three of them succeeded in implementation of the project. Only project 9 had won a challenge for new healthcare innovations. The price of the challenge was support for the development of their business plan, and support for the design and the development of the app. Researchers were convinced that they should be able to introduce the product to the market with a small amount of money: “The money comes from public funds, in our case not from a public subsidy provider, but still it is meant for a public goal: improving healthcare. The prices of publishers for publishing a self-management tool differ a lot, and you know that some publishers profit more than others. Of course we choose the cheapest publisher for our tool, because a tool will also become more attractive for the healthcare market” (researcher, project 3). Business partners indicate that, in addition to a relatively low price, it is important to understand who will be responsible for the costs of implementing a product in the healthcare market. Upscaling to different target groups is a way to achieve a business case: “The business model is really important once the tool is available in the market. When the budget of the subsidy has been used, the tool actually stagnates, yet a digital tool needs continuous attention. So with every update from a browser, every update from iOS or from Android, the app must be tested and adapted to the update. For that you need ongoing income. So you have to have paying customers. That, of course, is a job in itself. How do you reach the market? How do you ensure that the product is marketed? That they pay for it? What is a fair price? Who runs the tool from that moment on? (...) If you want to keep such an app up and running, then you have to charge a few thousand euros a year for each physical therapist, and that is too much. We now simply have a very general service, which costs 10 euros per physical therapist per month. Physical therapists already find that very expensive” (partner, project 2).

In addition to the financial aspect, healthcare providers need to work in a different way which is a complicated organisational change process for healthcare organisations: “It is a new way of working. Breaking routines takes time, and therefore the owner of a healthcare organisation is sometimes not so enthusiastic about it” (researcher, project 2). Another obstacle researchers and developers need to deal with is the link of the programme with the electronic patient file (EPD). There exist multiple patient files, and a programme should match with the EPD, and if it is suited to the EPD a programme makes healthcare, in particular the administrative tasks, more efficient: “Now I give children a homework booklet, and then I have to enter it manually in an EPD. If you do that via an app and that is immediately entered into an EPD, that saves time and you also have an efficiency of information” (healthcare partner, project 5).

In some cases, changes are also needed in the healthcare system. For example, efficiency is not rewarded in the case of physiotherapists: “As a physiotherapist you get paid per session, so if you get fewer sessions, you have less income. And if you are not rewarded for the more efficient treatment, it is of course no incentive to use that, no matter how satisfied your patient is” (healthcare partner, project 5). For researchers it is difficult to work together with healthcare insurance organisations, but for some business partners and healthcare organisations cooperation is possible, especially when there is an increase in scale: “We need the upscaling of physiotherapy practices because we want to achieve a national coverage for cooperation with national organisations … We noticed that even when we are in conversation with other organisations, such as health insurers and the government, they also prefer national coverage” (partner, project 2).

In addition to the discussed factors originating from the narrative review, the cases also offered two other important factors that could promote the implementation success of self-management innovations. First, the drive of the implementation team. The implementation depends on the team members who really want to implement the self-management health innovation: “The implementation does not even start until there are enough people who are really passionate about the innovation, are driven to achieve success, and who believe that the innovation can really make the difference for the target group. You must continuously connect different stakeholders to reach the right people at the user, organisation, and the wider system level. You need a lot of passion to do that” (healthcare professional, project 5). Second, it is difficult for researchers at UASs to implement a self-management health innovation, because they do not have the knowledge and expertise for the implementation of their innovation and miss the support from the UAS: “as a researcher you are not yet a marketer or product developer. It really took a lot of effort and perseverance, and it took a lot of time to get it there. I thought it was important, because I think — there is no value in having a concept in a display cabinet. It is difficult to find the expertise you need for marketing, development, production, and legalisation in an institution such as a UAS” (researcher, project 3).

Up to this point, the identified factors to foster implementation success of self-management health innovations were described; the next section shows the factors related to implementation success based on the cross-case analysis.

Factors related to implementation success

The third part of the result section describes to what extent the factors have led to a successful implementation of self-management health innovations in the nine studied research projects at UASs. These have been related to the conceptual model. Table 4 below presents the mentioned factors for each project as described in the previous section. The columns represent the nine projects (1–9). On the rows, the nine factors found in the narrative review of academic literature are shown. The mentioned factors in each research project are marked with a ‘1’ in Table 4.

Although each case is different, there are also similarities to be identified: each of them involved end-users, developed the innovation in a multi-disciplinary team, and developed the innovation by iterative evaluation cycles. Although these factors could be an important condition for a successful implementation, these factors are apparently insufficiently explanatory to foster successful implementation of self-management health innovations, because only three projects achieved a successful implementation of a self-management health innovation. The involvement of end-users during the development phase was helpful; patients could also be disappointed when a product is not available and ready for implementation: “Before the introduction of a prototype, the prototype sometimes should be closer to completion. If you have consulted or tried out the concept with someone and the basic idea could work well, then you should continue with a product that is actually good and not try it again with some adjustments. Overall, it is disappointing for clients that a product is still not available for them” (healthcare professional, project 4). The utilisation of multiple disciplines is also a factor that is present in all projects, and is seen by previous literature as a condition for a successful implementation, but at the same time it is a factor that requires adequate cooperation within the team, in which expectations are expressed: “We assumed that the software developers would make a product for us and that a business partner could then use and market that app, but that is not how it actually works. A business partner rebuilds such an app anyway. If we had known that the developers only had to make a prototype for the project, that would have saved a lot of time. And it would help us if they had given us this information before” (researcher, project 5).

Table 4 shows that only one of the projects (project 2) involved the factor Anticipation of changes required in the healthcare system. Five other projects also tried to involve healthcare insurance organisations in the beginning of the project, without success. For collaboration in an innovation project, these financing organisations first want a guarantee that the innovation will actually have an effect. The other two factors related to the use context, Availability of a feasible business model and Adaption to organisational changes, were also included in only a few cases. Four projects did involve a business partner, with the aim that the business partner could play a role in developing the innovation or putting the innovation into production or into the market. Some of these business partners dropped out during the project, because the further development of the prototype was more expensive than the expected reward. One of the business partners who decided to postpone developing the tool said: “The group of child physiotherapists in the Netherlands is too small if you want to start selling an app. You have to develop the app and pay for it, keep it up and running in terms of service. It is too expensive for the users. It would be better if we could add it to the existing service and make those functionalities not only available for child physiotherapists, but also for speech therapists and other professional groups.” (business partner, project 5). Some projects did not aim to deliver a market-ready product: “The goal was to make a prototype, but with the promise that we would do something with it” (researcher, project 4).

Project 2 included all factors in their implementation process. This project also succeeded in implementing a self-management health innovation. On the other hand, the other two projects who also succeeded in an implemented self-management health innovation did not include all factors in the project. These two projects (projects 1 and 3) abandoned their initial idea of creating a digital technology tool, such as an e-health application, in favour of a non-technical product, such as an intervention tool in the form of a workbook and a game, to increase the chance for a successful end-product. Time and a limited budget formed the main reasons for changing plans. Projects 8 and 9 both include seven of the nine factors, and they have not succeeded in implementation yet. Both projects worked on a technological innovation in the form of an e-health application, which might require more time to implement. The two projects who did not include all factors and still succeeded in an implemented self-management health innovation (projects 1 and 3) have also abandoned the idea of a tailor-made innovation by opting for a non-technological innovation. In five of the studied projects, tailoring of the innovation was seen as an important factor, but tailoring innovations does not appear to be a condition for success. In fact, it can also make innovation too expensive.

In sum, the literature on the success of self-management health innovations reports nine distinct, although interrelated, factors for successful implementation of self-management health innovations. We empirically analysed in nine UAS self-management health innovation projects if these research projects are associated with these factors, to increase their implementation success, and we found that only in one successful implemented self-management health innovation project were all factors present.

Conclusion

Self-management is a promising approach to improve outcomes and reduce the healthcare costs associated with chronic conditions. Several self-management models have enhanced the understanding of characteristics of self-management products and their embedding in the healthcare system. However, less attention has been paid in these models to the factors leading to the implementation of self-management products. By performing a review of academic literature and a multiple qualitative case study, we were able to answer the following research question: which factors play a role in the successful implementation of self-management health innovations?

In studies reporting on the implementation process of self-management health innovations, we found nine factors: 1) involvement of end-users, 2) involvement of local and business partners, 3) involvement of stakeholders within the larger system, 4) tailoring of the innovation, 5) utilisation of multiple disciplines, 6) feedback on effectiveness, 7) availability of a feasible business model, 8) adaption to organisational changes, and 9) anticipation of changes required in the healthcare system.

When applying these success factors to a range of case studies in the context of self-management health innovation projects, we found that the success factors are neither necessary nor sufficient conditions for successful implementation of self-management health innovations. In the nine case studies, on average six factors could be identified. Only in one case were all factors present. No pattern or relationship was found between the presence of the nine success factors and the implementation success of the self-management innovation project.

Discussion

We started with an overview of academic literature from three scientific disciplines — research impact, innovation sciences, and marketing — based on the idea that each of these disciplines would add a specific point of view regarding success factors for implementation of self-management health innovations. The aim of this paper was to better understand which factors play a role in the successful implementation of self-management health innovations. Hereby, we found that nine factors could contribute to successful implementation of self-management health innovations. However, the findings in our multiple case study showed that this set of factors is neither necessary nor sufficient for successful implementation. Relevant to implementation we aimed to cover: 1) processes of utilising knowledge of research projects and of transferring knowledge from research to practice by the research impact discipline, 2) the innovation and development processes of self-management health products and services by the innovation science discipline, and 3) the adoption process of patients and healthcare providers by the marketing discipline. All these three viewpoints emphasise the importance of the process. Therefore we imagine that this process-based approach should be followed in further research.

We acknowledge that the overview of academic literature is not exhaustive. Our decision to limit our focus to innovation sciences, marketing, and research impact may have led to an under-representation of dimensions of self-management health innovations reported in studies that focus on, for example, social welfare policies, process organisation studies, technology, or health inequities at the local level. Our decision to start with a selection of journals instead of doing a full systematic review has narrowed down our scope. At the same time, using journals as entrance points for searching (sub)disciplines is common practice in narrative literature reviews (Green et al. 2006) or scientometric research (Cozzens and Leydesdorff 1992). In addition, in the first round the papers were selected for this overview on the basis of abstract content only, and we may have missed factors related to the implementation of self-management health innovations in the full article. However, our overview of academic literature was nevertheless comprehensive with regard to its purpose, namely finding factors which play an important role in the successful implementation of self-management health innovations. The literature/field on implementation of self-management health innovations is rapidly changing. A large number of the identified papers have been published within the last 5 years.

For our case study, several limitations of our qualitative multiple case study could be mentioned. First, success factors could only be analysed if the available documents or interviewee explicitly described a research activity or factor. Other learnings from the project are not included in this study. Second, since the main researchers have most knowledge about the project, they were the most important source in our data collection. For all projects, we interviewed the main researcher and another stakeholder, but we were aware that we missed perspectives of other involved stakeholders. This might result in a biased picture of the projects. However, we do think that this bias may be limited because we always included two perspectives, that of the main researcher and that of another stakeholder, and in all cases the two perspectives did not reveal real differences about the factors found. In addition, some researchers, business partners, and healthcare professionals were also involved in other cases and were able to compare cases and add information about other cases. Third, we focused on finished or almost finished self-management health innovation projects at one UAS. This enabled us to gain insights into the implementation of research projects in one UAS network. Further research could focus on a broader set of projects including at other UASs to determine to what extent the findings are context specific.

The aim of this paper was to explore which factors contribute to a successful implementation of self-management health innovations. The findings of this paper are an attempt to gain insights into the success factors project teams should take into account for successful implementation of self-management health innovations. This has not been put centre stage in extant self-management literature for which healthcare literature (Wagner et al. 1996; Lorig and Holman 2003; Grey et al. 2006; Ryan and Sawin 2009) served as inspiration. For successful implementation of self-management health innovation projects, the factors identified in the literature are neither necessary nor sufficient. One explanation could be that the domain of healthcare and self-management health innovations is too complex to just take into account one set of factors. There seem to be different perspectives to success factors; for example, the end-users could be involved too early in the process, as a healthcare professional mentioned: “Sometimes a product must be closer to completion before you introduce it. If you have consulted or tried out the concept with someone and the basic idea is working or could work well, then you should continue with a product that is actually good and not try it again with some adjustments. Overall, it is disappointing for clients that a product is still not available for them” (healthcare professional, project 4). This quote shows that not only the characteristic or the factor, but also the timing of the process is important. Therefore, it might also be insightful to study the research pathways over time, focusing on how researchers implement or do not implement an innovation instead of solely focusing on the factors that could be helpful in this process (Langley and Tsoukas 2017). More research is needed to understand how such a process model for innovation provides further insights into the implementation success of self-management health innovations.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset analysed and data extraction tools used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- UAS:

-

University of Applied Sciences

References

Adepoju OE, Bolin JN, Ohsfeldt RL, Phillips CD, Zhao H, Ory MG, Forjuoh SN (2014) Can chronic disease management programs for patients with type 2 diabetes reduce productivity-related indirect costs of the disease? Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Population Health Management 17(2):112–120

Ahn S, Smit ML, Altpeter M, Post L, Ory MG (2015) Healthcare cost savings estimator tool for chronic disease self-management program: a new tool for program administrators and decision makers. Front Public Health 3:42

Barlow J, Bayer S, Curry R (2006) Implementing complex innovations in fluid multi-stakeholder environments: experiences of ‘telecare’. Technovation 26:396–406

Barlow J, Turner A, Wright C (2000) A randomized controlled study of the arthritis self-management programme in the UK. Health Educ Res 15(6):665–680

Bodenheimer T, Wagner, Grumbach K (2002) Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA 288(14):1775–1779

Brady TJ, Murphy L, O'Colmain BJ, Beauchesne D, Daniels B, Greenberg M, House M, Chervin D (2013) A meta analysis of health status, health behaviors, and healthcare utilization outcomes of the chronic disease self management program. Prev Chronic Dis 10:120112

Cozzens SF, Leydesdorff L (1992) Journal systems as macroindicators of structural changes in the sciences. In: Van Raan AFJ et al. (Eds.) Proceedings of the International Joint EC – Leiden Conference on Science & Technology Indicators, Leiden, October 1991). DSWO-Press, Leiden, pp 453-467

Denford S, Campbell JL, Frost J, Greaves CJ (2013) Processes of change in an asthma self-care intervention. Qual Health Res 23(10):1419–1429

Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A (2006) Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med5(3):101–117

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O (2004) Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q 82(4):581–629

Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Papoutsi L, Lynch J, Hughes G, A’Count C, Hinder S, Proctor R, Shaw S (2018) Analysing the role of complexity in explaining the fortunes of technology programmes: empirical application of the NASSS framework. BMC Med 16:66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1050-6

Gray CM, Hunt K, Lorimer K, Anderson A, Benzeval M, Wyke S (2011) Words matter: a qualitative investigation of which weight status terms are acceptable and motivate weight loss when used by health professionals. BMC Public Health 11:513

Grey M, Knafl K, McCorkle R (2006) A framework for the study of self- and family management of chronic conditions. Nurs Outlook 54(5):278–286

Hendy J, Chrysanthaki T, Barlow J, Knapp M, Rogers A, Sanders C, Bower P, Bowen R, Fitzpatrick R, Bardsley M, Newman S (2012) An organisational analysis of the implementation of telecare and telehealth: the whole systems demonstrator. BMC Health Serv Res 12:403. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-403

Janssen M, Moors EHM (2013) Caring for healthcare entrepreneurs: toward successful entrepreneurial strategies for sustainable innovations in Dutch healthcare. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 80(7):1360–1374

Jonkman N, Schuurmans M, Jaarsma T, Shortridge-Baggett L, Hoes A, Trappenburg J (2016) Self-management interventions: proposal and validation of a new operational definition. J Clin Epidemiol 80:34–42

Langley A, Tsoukas H (2012) Introducing ‘perspectives on process organization studies’, In: Hernes T., Maitlis S. (eds.). Process, Sencemaking and Organizing, Oxford University Press: Oxford

Lorig KR, Holman H (2003) Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med 26(1):1–7

Macdonald W, Rogers A, Blakeman T, Bower P (2008) Practice nurses and the facilitation of self-management in primary care. J Adv Nurs 62(2):191–199

McColl-Kennedy J, Vargo S, Dagger T, Sweeney J, Van Kasteren Y (2012) Healthcare customer value cocreation practice styles. J Serv Res 15(4):370–389

Moors EHM (2013) Duurzaam innoveren: de kunst van het verbinden. Inaugural speech. Utrecht. Utrecht University, The Netherlands

Mort M, Roberts C, Callen B (2013) Ageing with telecare: care or coercion in austerity? Sociol Health Illn 6(35):799–812

Papa A, Mital M, Pisano P, Del Giudice M (2020) E-health and wellbeing monitoring using smart healthcare devices: An empirical investigation. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 153(C). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.02.018

Peine A, Moors EHM (2015) Valuing health technology — habilitating and prosthetic strategies in personal health systems. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 93:68–81

Pijlman H, Andriessen D, Goumans M, Jacobs G, Majoor D, Cornelissen A, Van Gennip K (2017) Advies werkgroep Kwaliteit van Praktijkgericht Onderzoek en het Lectoraat. Vereniging Hogescholen, Den Haag

Rabin BA, Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Kreuter MW, Weaver NL (2008) J Public Health Management Practice 14(2):117–123

Ryan P, Sawin K (2009) The individual and family self-management theory: background and perspectives on context process, and outcomes. Nurs Outlook 57(4):217–225

Sanders C, Rogers A, Bowen R, Bower P, Hirani S, Cartwright M, Fitzpatrick R, Knapp M, Barlow J, Hendy J, Chrysanthaki T, Bardsley M, Newman, S (2012) Exploring barriers to participation and adoption of telehealth and telecare within the Whole System Demonstrator trial: a qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research 12:220. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-220

Shaw J, Shaw S, Wherton J, Hughes G, Greenhalgh T (2017) Studying scale-up and spread as social practice: theoretical introduction and empirical case study. J Med Internet Research 19(7):e244. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7482

Shulman R, Miller F, Daneman D, Guttman A (2016) Valuing technology: a qualitative interview study with physicians about insulin pump therapy for children with type 1 diabetes. Health Policy 120: 64–71

Tavory I, Timmermans S (2014) Abductive analysis: theorizing qualitative research. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Wagner E, Austin B, Von Korff M (1996) Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q 74(4):511–544

Walters B, Adams S, Nieboer A, Bal R (2012) Disease management projects and the Chronic Care Model in action: baseline qualitative research. BMC Health Serv Res 12:114. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-114

Yin RK (1994) Case study research design and methods: applied social research and methods series (Second edn.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc

Yin RK (2009) Case study research: design and methods (4th edn.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications

Zwerink M, Brusse-Keizer M, Van der Valk PDLPM, Zielhuis GA, Monninkhof EM, Van der Palen J, Frith PA, Effing T (2014) Self management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD002990. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002990.pub3

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kees Greve for the his work in the coding of the narrative review.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wilke van Beest, Wouter Boon, and Daan Andriessen conceptualized the study. Wilke van Beest analysed the papers. Wouter Boon, Daan Andriessen, Ellen Moors, Gerrita van der Veen, and Harald Pol assisted in the review of papers for inclusion. All authors contributed to the final reviews of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Beest, W., Boon, W.P.C., Andriessen, D. et al. Successful implementation of self-management health innovations. J Public Health (Berl.) 30, 721–735 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01330-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01330-y