Summary

The dynamic course of Rett syndrome (RTT) is still said to begin with a period of apparently normal development although there is mounting evidence that individuals with RTT show behavioural peculiarities and abnormalities during their infancy. Their spontaneous general movements are abnormal from birth onwards. Normal cooing vocalisation and canonical babbling (if at all required) are interspersed with abnormalities such as proto-vowel and proto-consonant alternations produced on ingressive airstream, breathy voice characteristics, and pressed or high-pitched vocalisations. The gestural repertoire is limited. Certain developmental motor and speech-language milestones are not at all acquired or show a significant delay. Besides abnormal blinking, repetitive and/or long lasting tongue protrusion, and bizarre smiling, there are already the first body and/or hand stereotypies during the first year of life. We are currently on a promising way to define a specific set of behavioural biomarkers pinpointing RTT.

Zusammenfassung

Die vorherrschende Lehrbuchmeinung über die Pathogenese des Rett-Syndroms (RTT) ist immer noch so, dass die frühe Entwicklung annähernd normal verläuft, obwohl Ergebnisse aus Elterninterviews, -fragebögen, aber auch aus Videoanalysen belegen, dass Patientinnen mit RTT bereits im Säuglingsalter auffällig sind. Ihre Spontanbewegungen („general movements“) sind nicht altersadäquat und qualitativ abnormal; ihre frühen Vokalisationen (z. B. das Gurren und das kanonische Lallen) sind zumindest intermittierend auffällig mit alternierenden Protovokalen und Protokonsonanten bei einwärts strömender Luft, hauchiger, gepresster oder hoher Stimme; das Repertoire an kommunikativen Gesten ist limitiert; bestimmte motorische, soziokommunikative und sprachliche Meilensteine werden nicht oder nur mit großer Verzögerung erworben. Neben einseitigem Blinzeln, wiederholter und lang anhaltender Zungenprotrusion sowie bizarrem Lächeln kommt es bereits im ersten Lebensjahr zum Auftreten von Stereotypien des Körpers oder der Hände. Mit diesen Befunden nähern wir uns derzeit der Definierung eines spezifischen Spektrums an frühen Auffälligkeiten, die typisch für das RTT sein könnten.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Rett syndrome and the analysis of its early behaviour

Mutations in the X‑linked gene encoding Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) account for 95–97 % of cases of Rett syndrome (RTT, MIM312750), a genetic disorder affecting neurodevelopment, predominantly in females [1, 2]. Among the key features of typical RTT are (a) stereotyped hand movements coinciding with a regression in purposeful hand use, and (b) a regression in expressive language [2–4]. The dynamic course of RTT is said to involve a period of apparently normal early development followed by a profound neurological regression and subsequent stabilization or partial recovery [2–4]. This view, however, contrasts with mounting evidence of behavioural peculiarities and abnormalities observable already during the first months of life (e. g. [5, 8]).

RTT is usually diagnosed around 3 years of age [9], and being a rare disease, there are hardly any possibilities except retrospective data analyses to track down the pathways of various developmental domains before the assumed loss of previously acquired functions. Retrospective analyses comprise (a) parental interviews and questionnaires including parental diaries and medical histories; and (b) home video analyses. Both methodological approaches have strengths and weaknesses. Limitations of interviews/questionnaires are (i) a long time lag between the period of interest and the interview/questionnaire, (ii) a memory bias of parents with affected children and (iii) the lack of parental training in the observation of certain developmental features, especially when it comes to qualitative aspects of behaviours [10, 11]. The analysis of family videos (recorded at a time when the caregivers were not aware of their child’s disorder) is a more reliable option to focus on prediagnostic behaviour. It allows the detailed description of observable phenomena and behavioural peculiarities. But, one must never conclude that the absence of a certain behaviour is definite as home videos are not standardised, and parents tend to record situations which they would like to keep as pleasant memory. Nevertheless, some peculiar behaviours or even abnormalities—often unrecognised by parents—do not escape the eye of the camera [10, 12].

The motor domain

Spontaneous general movements

The assessment of the quality of early spontaneous movements, also known as the Prechtl assessment of general movements (GMs), has repeatedly proven to be a valuable tool in detecting early markers for neurodevelopmental disorders (e. g. [13–16]). GMs are generated by a neural network, the central pattern generators (CPGs), which are most likely located in the brainstem [14, 17]. GMs involve the entire body in a variable sequence of neck, arm, trunk and leg movements. Supraspinal projections activate, inhibit and most importantly, modulate the CPG activity, as does the sensory feedback [14, 17]. Reduced modulation of the CPG results in less variable (i. e. abnormal) movements and indicates neonatal or young infant’s compromise (e. g. [13, 14, 16]).

Already the very first reports on viewing some of the family videos (later used for a more detailed analysis [7, 18]) revealed the impression that infants later diagnosed with RTT moved in a jerky and uncoordinated way [19]. Detailed analysis including GM assessment [14] demonstrated that their GMs were clearly impaired (Table 1). Within the first 2 months of life, infants later diagnosed with RTT had already poor repertoire GMs [7, 18, 20, 21]; the sequence of their movement components was monotonous and the intensity, speed, and range of motion lacked the normal variability [13, 14].

In typical development a new pattern of GMs, the so-called ‘fidgety movements’ emerge at the beginning of the 3rd month [13, 14]. Fidgety movements are small movements of the neck, trunk and limbs in all directions and of variable acceleration; they last until the end of the 5th month when intentional movements become predominant [14, 22]. If fidgety movements are present and normal in their quality, infants will very likely develop normally [13, 23]. None of the 16 infants with a later diagnosis of RTT (reported in the literature) ever showed normal fidgety movements; their fidgety movements were either absent or abnormal, i. e. jerky and too slow, or jerky and abrupt [7, 18, 21].

In addition to these early movement abnormalities, subtle disturbances of muscle tone [5–7, 20, 24–26] and tremulous movements [7] were already observable during the first months of life.

Gross motor performance

In one of our first retrospective video analyses of infants later diagnosed with RTT we found that all 22 participants had the head centred in the midline by the 3rd month. When they had reached the end of their 6th month, almost all infants were able to roll over, and 3/22 infants were already able to sit without support [7]. Similar results were reported in the so far largest retrospective study based on parental interview. Nearly all of the 542 females with typical RTT were reported to have had acquired gross motor milestones such as rolling and sitting with support [27]. However, other more advanced gross motor behaviours such as sitting alone (80 %), crawling (69 %), pulling to stand (62 %), or walking alone (53 %) were less likely acquired [27], and if so, a significant developmental delay was reported [20, 25, 27, 28].

Fine motor performance

Witt-Engerström [29] discussed RTT as affecting the voluntary arm and hand movements even before hand skills were lost. Although >73 % of infants and toddlers with a later diagnosis of RTT acquired—albeit most of them delayed—fine motor behaviours such as reaching, transferring an object, pincer grasping or finger feeding [27], video analyses demonstrated that 14/24 infants (58 %) hardly manipulated toys but just touched them with extended fingers [7, 20, 30].

The first body and hand stereotypies

Repetitive limb and trunk movements, and small twitching movements of eyes and mouth were among the behavioural peculiarities described for the first year of life [19, 31]. In our own study we observed two 5‑month-old girls with stereotyped side-to-side body rocking while simultaneously shacking or nodding the head [7].

Meticulous video analyses revealed that the following hand stereotypies were clearly recognisable within the first months of life: repetitive opening and closing of the hand(s), excessive hand patting, twisting movements of the wrists and arms, uni- or bilateral repetitive pronation of the hand with simultaneous dorsiflexion of the wrist or repeated bringing of the palmar sides of both hands together, raising both hands and separating them [7, 19, 20, 29–32]. By contrast to later stages of RTT, hand stereotypies in the first year of life are still interspersed with a variety of normal and purposeful hand movements and postures [7, 20, 30].

The speech-language and socio-communicative domain

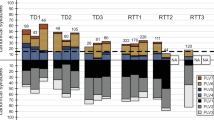

Typically developing children begin to communicate through pre-linguistic vocalisations, eye gaze, responsive smiling and gestures to express their wants and needs before they produce their first (proto-)words. Audio-video analysis but also parental questionnaires revealed that infants later diagnosed with RTT had besides motor abnormalities also deviant behaviours in their developing speech-language and socio-communicative domain (Table 1).

The eyes and the smile

In the so far largest sample analysed from home videos [7], almost all 1‑ to 6‑month-old infants later diagnosed with RTT were visually interested and demonstrated adequate visual pursuit. Apart from their early visual interest, a considerable number of infants (41 %) had strabismus, and more than half of the infants (56 %) had asymmetric opening of the eye lid after a blink (lasting even up to a few minutes) or asymmetric closing of the eye lid during a blink [7].

Although parental interviews revealed social smiling in almost all infants with a later diagnosis of RTT [27], several home video analyses displayed a frozen, bizarre or inadequate smile during the first months of life [6, 7, 20, 26]. Also, frequent and partly long-lasting tongue protrusions were observed from the first month onwards [7, 20, 29].

Early pre-linguistic vocalisations

Although parental interviews revealed that the majority of infants with a later diagnosis of RTT had developed early speech-language milestones such as cooing (93 %) or babbling (95 %) [27], detailed analysis of family videos demonstrated that this was not the case for all individuals [8]. As mentioned above, both methodological approaches have their limitations: (a) parents are naïve observers in describing (pre-)linguistic phenomena, (b) they might not remember details of certain behaviours happening a few years earlier, and (c) the linguistic corpus is always defective as it never covers the whole set of vocalisations present. Hence, we need to be cautious in drawing conclusions if a certain developmental milestones was age-adequately acquired. On the other hand, audio-video analyses have the strength to focus on the complexity, composition and quality of early vocalisations (including low-level descriptors [33]). In this respect, it turned out that a considerable number of infants later diagnosed with typical RTT [8, 34] but also with the preserved speech variant [34–36] presented abnormal vocalisations on inspiratory airstream. Especially from 3 months onwards, normal cooing vocalisation was interspersed by proto-vowel or proto-consonant alternations produced on ingressive airstream, breathy voice characteristics, and pressed or high-pitched vocalisations [8, 33–37].

The majority of infants with available recordings on canonical babbling demonstrated again an interspersed pattern of typical and atypical babbling [8, 34]. These deviant characteristics in early vocalisations of infants later diagnosed with RTT could be accurately identified by 400 participants of a listening experiment. The rating of canonical babbling led to a more accurate differentiation between typically developing infants and infants later diagnosed with RTT as compared to cooing vocalisations [37].

Gestures

First gestures such as demonstrating and/or passing an object, index finger pointing, and reaching towards the caregiver usually emerge around 10 to 12 months of age. Although the age of onset of the first gestures was adequate in infants with a later diagnosis of RTT, the gestural repertoire was limited [11, 20, 26, 38, 39]. Symbolic gestures such as nodding the head were observed in a very limited number of infants later diagnosed with RTT. It remained however open if this gesture conveyed a meaning or was rather a perseverative motor pattern [11, 39]. The gestural repertoire was limited in terms of number but also in its usage, i. e. the pragmatic functions mainly observed were attention to self, requesting an action or object, or imitation [11, 39].

The first (proto-)word

According to audio-video analyses of family videos hardly any infant later diagnosed with typical RTT spoke proto-words (3/19; 16 %) [8, 20, 34, 39], and none of them produced word combinations during the second year of life [8].

Conclusion

Individuals with RTT may achieve certain developmental milestones such as standing and walking alone, babbling, using gestures and/or speaking the first words. A series of studies have, however, shown that these milestones bear important information if we look beyond the yes/no (achieved/not achieved) dichotomy. Qualitative deviances, among them abnormal GMs and/or abnormalities in cooing and babbling account for CPG involvement in the brainstem [7, 14, 17, 40, 41]. Our understanding of the ways in which MECP2 impacts early brain development is constantly evolving. Deficiencies in both organisation and refinement of early neural circuits, altered neurogenesis, and aberrant cell signalling might explain some of the early developmental abnormalities (for review see [42]).

Although Table 1 provides a list of early signs in infants later diagnosed with RTT, we know that certain deviations are shared by individuals with other neurodevelopmental disorders. Further (multicentre) studies are essential (a) to sort out the specific set of early behavioural biomarkers pinpointing RTT, and (b) to elucidate interconnectivity and (the lack of) modulation of CPG activities, which are crucial for the very early (dys)function of motor and vocalisation behaviours.

References

Amir RE, van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in x‑linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat Genet. 1999;23:185–8.

Neul J, Kaufmann WE, Glaze DG, Christodolou J, Clarke AJ, Bahi-Buisson N, et al. Rett syndrome: revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:944–50.

Rett A. Über ein eigenartiges hirnatrophisches Syndrome bei Hyperammonemie im Kindesalter. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1966;116:723–6.

Hagberg B, Aicardi J, Dias K, Ramos O. A progressive syndrome of autism, dementia, and loss of purposeful hand use in girls: Rett’s syndrome: Report of 35 cases. Ann Neurol. 1983;14:471–9.

Leonard H, Bower C. Is the girl with Rett syndrome normal at birth? Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998;40:115–21.

Burford B, Kerr AM, Macleod HA. Nurse recognition of early deviation in development in home videos of infants with Rett disorder. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2003;47:588–96.

Einspieler C, Kerr AM, Prechtl HFR. Is the early development of girls with Rett disorder really normal? Pediatr Res. 2005;57:696–700.

Marschik PB, Kaufmann WE, Sigafoos J, Wolin T, Zhang D, Bartl-Pokorny KD, et al. Changing the perspective on early development of Rett syndrome. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34:1236–9.

Tarquinio DC, Hou W, Neul JL, Lane JB, Barnes KV, O’Leary HM, et al. Age of diagnosis in Rett syndrome: patterns of recognition among diagnosticians and risk factors for late diagnosis. Pediatr Neurol. 2015;52:585–91.

Marschik PB, Einspieler C. Methodological note: Video analysis of the early development of Rett syndrome – One method for many disciplines. Dev Neurorehabil. 2011;14:355–7.

Marschik PB, Sigafoos J, Kaufmann WE, Wolin T, Talisa VB, Bartl-Pokorny KD, et al. Peculiarities in the gestural repertoire: An early marker for Rett syndrome? Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33:1715–21.

Saint-Georges C, Cassel RS, Cohen D, Chetouani M, Laznik MC, Maestro S, et al. What studies of family home movies can teach us about autistic infants: A literature review. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2010;4:355–66.

Prechtl HFR, Einspieler C, Cioni G, Bos AF, Ferrari F, Sontheimer D. An early marker for neurological deficits after perinatal brain lesions. Lancet. 1997;349:1361–3.

Einspieler C, Prechtl HFR. Prechtl’s assessment of general movements: A diagnostic tool for the functional assessment of the young nervous system. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2005;11:61–7.

Bosanquet M, Copeland L, Ware R, Boyd R. A systematic review of tests to predict cerebral palsy in young children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55:418–26.

Einspieler C, Bos AF, Libertus M, Marschik PB. The general movement assessment helps us to identify preterm infants at risk for cognitive dysfunction. Front Psychol. 2016;7:406. doi:10.3389/psyg.2016.00406.

Einspieler C, Marschik PB. Central pattern generators and their significance for the foetal motor function. Klin Neurophysiol. 2012;43:16–21.

Einspieler C, Kerr AM, Prechtl HFR. Abnormal general movements in girls with Rett disorder: The first four months of life. Brain Dev. 2005;27:S8–S13.

Kerr AM, Montague J, Stephenson JB. The hands, and the mind, pre- and postregression, in Rett syndrome. Brain Dev. 1987;9:487–90.

Einspieler C, Marschik PB, Domingues W, Talisa VB, Bartl-Pokorny KD, Wolin T, et al. Monozygotic twins with Rett syndrome: phenotyping the first two years of life. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2014;26:171–82.

Einspieler C, Sigafoos J, Bartl-Pokorny KD, Landa R, Marschik PB, Bölte S. Highlighting the first 5 months of life: General movements in infants later diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder or Rett syndrome. Res Autism Spectr Dis. 2014;8:286–91.

Einspieler C, Marschik PB, Prechtl HFR. Human motor behaviour. Prenatal origin and early postnatal development. Z Psychol. 2008;216:148–54.

Einspieler C, Peharz R, Marschik PB. Fidgety movements – tiny in appearance, but huge in impact. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2016;92:S64–S70.

Naidu S. Rett syndrome: A disorder affecting early brain growth. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:3–10.

Nomura Y, Segawa M. Clinical features of the early stage of the Rett syndrome. Brain Dev. 1990;12:16–9.

Burford B. Perturbations on the development of infants with Rett disorder and the implications for early development. Brain Dev. 2005;27:S3–S7.

Neul JL, Lane JB, Lee HS, Geerts S, Barrish JO, Annese F, et al. Development delay in Rett syndrome: data from the natural history study. J Neurodev Disord. 2014;6:20–9.

Segawa M. Early motor disturbances in Rett syndrome and its pathophysiological importance. Brain Dev. 2005;27:S54–S58.

Witt-Engerström I. Rett syndrome: a retrospective pilot study on potential early predictive symptomatology. Brain Dev. 1987;9:481–6.

Essl M. Development of hand function and stereotypies in Rett syndrome during the first year of life. Diplomarbeit. Medical University of Graz; 2013., p 149.

Kerr AM. Early clinical signs in Rett disorder. Neuropediatrics. 1995;26:667–71.

Temudo T, Maciel P, Sequeiros J. Abnormal movements in Rett syndrome are present before the regression period: A case study. Mov Disord. 2007;22:2284–7.

Pokorny FB, Marschik PB, Einspieler C, Schuller BW. Does she speak RTT? Towards an earlier identification of Rett syndrome through intelligent pre-linguistic vocalisation analysis. Proceed Interspeech. 2016, in press.

Marschik PB, Bartl-Pokorny KD, Tager-Flusberg H, Kaufmann WE, Pokorny F, Grossmann T, et al. Three different profiles: Early socio-communicative capacities in typical Rett syndrome, the preserved speech variant and normal development. Dev Neurorehabil. 2013;17:34–8.

Marschik PB, Einspieler C, Oberle A, Laccone F, Prechtl HF. Case report: retracing atypical development: a preserved speech variant of Rett syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39:958–61.

Marschik PB, Einspieler C, Prechtl HFR, Oberle A, Laccone F. Relabelling the preserved speech variant of Rett syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:218.

Marschik PB, Einspieler C, Sigafoos J. Contributing to the early detection of Rett syndrome: The potential role of auditory Gestalt perception. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33:461–6.

Tams-Little S, Holdgrafer G. Early communication development in children with Rett syndrome. Brain Dev. 1998;18:376–8.

Bartl-Pokorny KD, Marschik PB, Sigafoos J, Tager-Flusberg H, Kaufmann WK, Grossmann T, et al. Early socio-communicative forms and functions in typical Rett syndrome. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34:3133–8.

Barlow SM, Lund JP, Estep M, Kolta A. Central pattern generators for orofacial movements and speech. In: Brudzynski SM, editor. Handbook of mammalian vocalization. An integrative neuroscience approach. Amsterdam: Academic Press; 2009. pp. 351–70.

Marschik PB, Kaufmann WE, Bölte S, Sigafoos J, Einspieler C. En route to disentangle the impact and neurobiological substrates of early vocalizations; Learning from Rett syndrome. Behav Brain Sci. 2014;37:562–3.

Feldman D, Banerjee A, Sur M. Developmental dynamics of Rett syndrome. Neural Plast. 2016;2016:6154080.

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Graz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

C. Einspieler, M. Freilinger and P.B. Marschik declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Einspieler, C., Freilinger, M. & Marschik, P.B. Behavioural biomarkers of typical Rett syndrome: moving towards early identification. Wien Med Wochenschr 166, 333–337 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10354-016-0498-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10354-016-0498-2