Abstract

Purpose

An incomplete linear staple line that was discovered during the stapling of an ileal pouch alerted us to evaluate potential usage concerns with linear cutters. This study was designed to assess the integrity of the staple line of three different sizes of linear staplers.

Methods

In an animal model three different lengths of linear cutters (Proximate®, Ethicon Endo-Surgery) were used to cross-staple and transect the large bowel of one pig to check for the integrity of the proximal end of the staple line.

Results

Cross-stapling and transecting across the pig’s large bowel demonstrated that if the tissue is advanced up to the highest number on the scale of the 100 mm stapling device, insufficient overlap between the proximal end of the staple line and the proximal end of the cut line occur.

Conclusions

Although a more than 100 mm staple line is delivered, the 100 mm cutter may not produce a double-staggered row of staples at the most proximal end of the staple line if the tissue is advanced past the 9.5 cm mark. Ethicon Endo-Surgery has agreed to add indicator markers to the scale label on the instrument to provide the user with additional guidance for tissue placement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Several risk factors for anastomotic insufficiency have been identified.1–3 Despite the identification of these risk factors, the actual cause or contributing factor(s) to anastomotic insufficiency is not always clear. With known risk factors aside, surgical instruments used, in particular stapling and cutting devices, could contribute to anastomotic insufficiency if they malfunction or are used inappropriately. Concerning surgical stapling devices, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) received reports of 22,804 malfunctions, 2,180 injuries, and 112 deaths from 1992 to July 1, 2001. These numbers included all types of linear and circular stapling devices as well as clip appliers. Most of these reports comprised device or user-related errors of linear cutters and staplers. Furthermore, the majority of operations reported were gastrointestinal. Failure of stapler devices to function or be used properly resulted in suture line separation or leak as the most commonly reported problem.4 However, when interpreting these data, it should be kept in mind that besides the fact that staplers are used very frequently, the exact denominator is not known. This subscribes the importance of understanding the correct usage of the device, as well as the appropriate surgical techniques to inspect and verify staple lines and staple formation, and the techniques to employ should issues occur.5 Nevertheless, despite correct usage, staple line failure might still occur. The following case alerted us to evaluate the function of a linear cutter (Proximate® 100 mm-TLC10, Ethicon-Endo Surgery, Inc., Cincinnati, OH).

Case

A patient with ulcerative colitis was referred for laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy because of recurrent disease relapses despite extended medicinal therapy (no steroid use preoperatively).

One firing of a 100 mm linear cutter (Proximate® TLC10) was used to construct the (relatively) small ileal pouch extracorporally. Subsequently, the anvil of the circular stapler was placed in the base of the pouch to create a double-stapled ileoanal anastomosis. The donuts were checked for their integrity and proved to be intact. During the operation, there was no significant blood loss and there were no intraoperative adverse events.

The procedure was ended by the transanal insertion of a 24 Fr Foley catheter (outside diameter 8 mm) in the pouch for temporary postoperative pouch decompression, because there was no indication for a defunctioning ileostomy. During insertion, it was noticed that the drain could be pushed in much further than expected without resistance. This unexpected observation urged reinstallation of the pneumoperitoneum. Inspection showed that the drain emerged in between the mesentery of the pouch and the pouch itself, suggesting a failure of the posterior linear staple line. Subsequently, the drain was pulled back and a defunctioning ileostomy was constructed. The defect in the pouch was not repaired because of its difficult approachability.

The gap in the staple line was identified at the most proximal end of the linear cutter staple line. After this incident, we investigated the proximal portion of the staple line of three different sizes of linear cutters after cross-stapling the large bowel of a pig.

Material and Methods

To investigate whether insufficiency of the proximal staple line would occur if cross-stapling of the bowel was performed according to the users’ manual, three different lengths of linear cutters from the same company (Proximate® 55 mm-TLC55, 75 mm-TLC75, and 100 mm-TLC10, Ethicon Endo-Surgery) were used to cross-staple the large bowel of one pig. The pig (female, 10 weeks old, weight 30 kg) was killed after a previous experiment that was not related to the bowel. The large bowel of a pig was chosen because this offered the same tissue characteristics as human tissue compared with artificial material (e.g., PTFE). The complete experiment was approved by the institutional animal ethics committee. Special attention was paid to the positioning of the bowel in the cutter; the tissue was not advanced further than the end marks on the cutter.

After firing the cutter, the proximal area of the two double-staggered rows of staples was photographed and visually evaluated for staple pattern and placement. Subsequently, in the presence of a gap in the staple line, the gap was measured by using a pair of pickups. The lab experiments were witnessed by representatives of the device manufacturer.

Results

Three different lengths of linear cutters (Proximate® 55 mm-TLC55, 75 mm-TLC75, and 100 mm-TLC10, Ethicon Endo Surgery) were used to cross-staple the large bowel of one pig. Each cutter was fired three times.

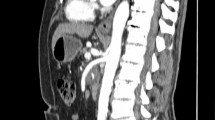

The cross-stapling of the pig’s large bowel demonstrated that the 100 mm cutter did not produce a double-staggered row of staples at the most proximal end of the staple line if the tissue was advanced up to the 10 mark on the stapling device. At the proximal end of the staple line, the bowel was cut but not stapled, resulting in a gap ranging between 3 and 5 mm (Fig. 1). The 55 mm and 75 mm cutters produced visually adequate staple line patterns, provided that the tissue was not squeezed or forced beyond the 5 (TLC55) and 7 (TLC75) marks, respectively, during closure of the stapler. If tissue was squeezed or forced proximal to these marks, cutting without stapling occurred. Inspection of the three sizes of linear cutters demonstrated that the 100 mm cutter does not have a staple overlap (double-staggered row) at the proximal end of the device. In Figure 2, it is shown that the two double-staggered rows of staples stop at the 9.5 mark and only a single staple is positioned proximally. Therefore, advancing the tissue to the 10 mark will cause cutting without stapling, resulting in a 5 mm gap. If the tissue is forced into the device while closing, the gap is even longer.

The proximal end of the 100 mm Proximate® linear cutter (TLC 100, Ethicon Endo-Surgery) in detail. The two double-staggered rows of staples stop at 95 mm and a single staple is positioned proximal. Users should not position the tissue up to the 100 mm mark because the cutter divides the tissue beyond 100 mm, resulting in a small gap of several millimeters.

Discussion

Both the presented case and animal model demonstrated that when using the 100 mm Proximate® linear cutter (TLC 10, Ethicon Endo-Surgery) care must be used when stapling tissue close to the proximal end of the cutter. As shown in Figure 2, the row of staples stops between the 10 and 9.5 indicators and only at the 9.5 mark a double-staggered row is present. Beyond this point, there is a possibility that the intestine is cut but not stapled, leaving a gap of several millimeters.

Postmarket surveillance data by the manufacturer for the TLC10 device during a two-year period showed no additional serious injury reports for leaking or incomplete staple lines, which potentially could be related to the described staple pattern. The incidence of clinically significant problems associated with this stapler is low, because it probably only occurs when the 100 mm cutter is used for its full length, stapling large bowel and pouches. Since the described incident occurred, we routinely inspect the pouch after linear stapling, both anteriorly and posteriorly, by inversion of the pouch to check for insufficiency of the proximal staple line. If an insufficiency is identified, it is most commonly located both anteriorly and posteriorly, and the gap can usually accommodate at least one leg of a pair of pickups (Fig. 3). On the posterior site, the hole is oversewn, and at the anterior site of the pouch the hole is incorporated in the pursestring of the anvil of the circular stapler. In case of a side-to-end colonic anastomosis, the proximal end of the cross-stapling line is routinely checked and oversewn if necessary.

Schematic drawing of the construction of a pouch using the 100 mm Proximate® linear cutter (TLC 10 Ethicon Endo-Surgery). A small gap of several millimeters arises when the cutter is used to its full length because of cutting without stapling (A, arrow). Both on the anterior and posterior site of the pouch, a small gap (*) is present because of cutting without stapling (B).

The observations in the animal model have been witnessed by employees of the manufacturer. The manufacturer has agreed to add indicator markers to the scale label on the instrument to provide the user with additional guidance for tissue placement. However, no further changes to the proximal part are planned. As shown in Figure 4, an arrow has been added to the scale labels of all three lengths of cutters to be consistent and to indicate recommended tissue placement. As a result of the findings presented in this paper, the following comment was added to the instructions for use: “Tissue to be transected must be located between the arrows marked on the instrument jaw. Any tissue located outside of the arrows is out of the stapling range.” The existing warning, “After removing the instrument, examine the staple lines for hemostasis/pneumostasis and proper staple closure,” is worth noting, because it is good clinical practice to check the staple line to ensure that tissue condition, technique, and device did result into an intact staple line. Whenever there is a question regarding the sealing of a staple line, it is advisable to perform a leak test. This is routinely recommended when using the circular staplers.

References

Alberts JC, Parvaiz A, Moran BJ. Predicting risk and diminishing the consequences of anastomotic dehiscence following rectal resection. Colorectal Dis 2003;5:478–82.

Matthiessen P, Hallbook O, Andersson M, Rutegard J, Sjodahl R. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after anterior resection of the rectum. Colorectal Dis 2004;6:462–9.

Soeters PB, de Zoete JP, Dejong CH, Williams NS, Baeten CG. Colorectal surgery and anastomotic leakage. Dig Surg 2002;19:150–5.

Brown SL, Woo EK. Surgical stapler-associated fatalities and adverse events reported to the Food and Drug Administration. J Am Coll Surg 2004;199:374–81.

Baker RS, Foote J, Kemmeter P, Brady R, Vroegop T, Serveld M. The science of stapling and leaks. Obes Surg 2004;14:1290–8.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supported in part by Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Johnson & Johnson.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Wind, J., Safiruddin, F., van Berge Henegouwen, M.I. et al. Staple Line Failure Using the Proximate® 100 mm Linear Cutter. Dis Colon Rectum 51, 1275–1278 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-008-9305-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-008-9305-5