Abstract

The number of fruits on the German and European markets with a carbon label is on the increase. This contribution reviews the existing carbon labels by evaluating, categorising and giving background information to provide guidance for labelling home-grown horticultural produce.

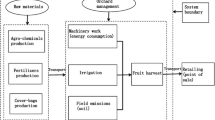

The existing labels worldwide were classified in 10 categories: (1) CO2 value; (2) Colour code (with or without CO2 value); (3) CO2 reduction (Carbon Trust, Tesco’s, UK) or conversion labels; (4) Climatop for Migros, Switzerland (temporal label for the best product within a product category, e.g., banana, rice, salt); (5) Airfreight labels, e.g., Marks & Spencer’s UK (without further information); (6) ‘Climate, carbon offset or CO2-neutral’, e.g., NewTree, (only when using gold standard CO2 emission certificates); (7) unaccounted CO2 compensation measures (such as planting young trees: ‘CO2 pineapple’ in Costa Rica); (8) Sustainability labels (ProPlanet, REWE), (9) sustainability reports (printed or online) and (10) QR-Code on the shelf or product to access web-based information. The ‘Pros and Cons’ of the climate labels are compared with respect to the seasonal fruit and vegetables often sold on the markets as lose items and the stakeholder interest. Labelling approaches 4, 8, 9 and 10 appeared suitable for seasonal fruits and vegetables based on criteria such as transparency, clarity, objectivity and integration in the sustainability context. Overall, it is difficult to use labels with a CO2 value for horticultural products, because (a) the consumer may find it difficult to judge and memorise numeric values, particularly if expressed on different units (e.g. packet size, 1 l, 100 g) and (b) because of the big variation between the farm production systems and the variability between the year to year weather and (c) the consumer may find shopping with a seasonal crop calendar and country of origin label a better choice.

Zusammenfassung

Auf dem deutschen bzw. europäischen Obstmarkt tauchen zunehmend Früchte mit CO2-Label auf. Dieser Beitrag soll einen kurzen Überblick über die verwendeten Label geben, sie analysieren, kategorisieren und ihren Hintergrund kurz erläutern und damit auch Anregungen für eine mögliche Vorgehensweise bei heimischem Obst und Gemüse geben.

Die vorhandenen Labels konnten in 10 Kategorien eingeteilt werden: 1) CO2- Wert; 2) Ampel (mit oder ohne CO2-Wert); 3) CO2- Reduktion (Carbon Trust); 4) Climatop (zeitlich begrenztes Label für die besten Produkte einer Produktkategorie- z. B. Banane, Reis, Salz); 5) Luftfrachtlabel (ohne weitere Angabe); 6) „Klima- oder CO2-neutral“, z. B. NewTree (nur anerkannt bei Zukauf von Gold CO2-Emissionszertifikaten); 7) nicht zertifizierte Kompensationsmaßnahmen ohne Anerkennung (z. B. lediglich durch Pflanzen junger Bäume bei der ‚CO2-Ananas‘ aus Costa Rica); 8) Nachhaltigkeitslabel (ProPlanet, REWE), 9) Nachhaltigkeitsberichte (gedruckt oder online) und 10) Informationszugang über QR-Code am Regal oder Produkt.

Beurteilt nach den Kriterien Transparenz, Verständlichkeit, Objektivität, Verlässlichkeit, Vergleichbarkeit und integrierbar ins Thema Nachhaltigkeit erschienen die Kategorien 4, 8, 9 und 10 für saisonale Lebensmittel – wie Obst und Gemüse – am besten geeignet. Ansprüche an ein und Vor- und Nachteile der CO2-Label werden für den Obst- und Gemüsemarkt mit witterungsbedingter, saisonaler Anbaupraxis mit variablen CO2-Wert und häufig loser Ware verglichen und die Auffassung der unterschiedlichen Interessensgruppen vorgestellt. Für den Konsumenten ist es zudem schwierig, einzelne CO2 -Werte an der Ware bei unterschiedlicher Bezugsgröße (z. B. Packung, 1 Liter oder 100 g) zu beurteilen, so dass bei Obst und Gemüse der Einkauf ohne Label, aber nach Saisonkalender und mit Herkunftsangabe die bessere Lösung ist.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Blanke M (2009) Von weit her eingeflogen? Rheinische Monatsschrift 97(1):16

Blanke M (2012) Der klimafreundliche Apfel von nebenan. InnoFrutta 1:1–6

Blanke M, Burdick B (2005a) Food (miles) for thought: energy balance for locally-grown versus imported apple from New Zealand. Environ Sci Pollut Res 12(3):125–127

Blanke M, Burdick B (2005b) Energiebilanzen für Obstimporte: Äpfel aus Deutschland oder Übersee? Erwerbs-Obstbau 47(6):135–137

Blomqvist O (2009) Different types of climate labels for food products, Master thesis, Lunds Universitet, Sweden

Boardman B (2008) Carbon labelling: too complex or will it transform our buying? Signif 5(4):168–171

BSI (2010) PAS2060- Carbon neutrality. Specifications for the demonstration of carbon neutrality. British Standards Institution BSI, London-Chiswick, UK

BSI (2011) PAS2050: October 2008. Specification for the assessment of life cycle green house gas emissions of goods and services. British Standards Institute BSI, London-Chiswick, UK

Denstedt C, Breloh L, Lüneburg-Wolthaus L, Blanke MM (2010) Carbon footprint of early imported strawberries from Huelva into Germany- from farm to fork. In: Notamicola B et al (eds) Proceedings of the LCA foods congress (Notamicola, B., et al., eds.), Universita degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro, 22-24 September 2012, Italy, 22–24 September 2012, Volume 1, pp. 499 ff

Eberle U (2010) Studie im Auftrag der Verbraucherzentralen zum CO2 Fußabdruck- Vergleich der label- http://www.verbraucherzentralen.de

Fleischer A (2010) ANEC- PCF labels potentially mislead and confuse. 4th PCF Summit-Thema 1- Berlin 20–21 October 2010

Hartikainen H et al (2012) Finish consumer understanding of carbon footprining and food product labelling. Proc. 8th Int. Conf on LCA in the Agri-Food Sector. 1–4 October 2012, St. Malo, Session 4A: Carbon Footprint, 1–4 October 2012, pp 353–355

IPCC (2007) Fourth assessment Report (AR4) [PDF document]. http://www.ipcc.ch/

Kahlert B (2013) “Climatop-Erfahrung mit einem Labelling-System im Lebensmittelbereich” Expert workshop on ‘CO2 certification and labelling’. Weihenstephan Triesdorf, 21 June, 2013

Rayner J (2007) Hall of fame- judges award: the man who invented “food miles”. OFM, Issue March 2007, 68–71

Schaefer F, Blanke MM (2012) Farming and marketing system affects carbon and water footprint-a case study using Hokaido pumpkin. J Clean Prod 28:113–119

Schaefer F (2014) Carbon Footprint ausgesuchter gartenbaulicher Kulturen im Rahmen eines Pilotprojektes zur neuen PAS2050-1- Bewertung der Treibhausgasemissionen entlang der Wertschöpfungskette. Dissertation, Universität Bonn

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schaefer, F., Blanke, M. Opportunities and Challenges of Carbon Footprint, Climate or CO2 Labelling for Horticultural Products. Erwerbs-Obstbau 56, 73–80 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10341-014-0206-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10341-014-0206-6

Keywords

- Biodiversity

- Carbon footprint

- Climate label

- Communication

- CO2 emissions

- Greenhouse gases (GHG)

- PAS2050-1

- Resource conservation

- Sustainability