Abstract

Dispersal is an important process in ecology, but its measurement is difficult. In particular, natal dispersal—the net movement between site of birth and site of first reproduction—is important, since it determines population structure. Using simulated data, I study the claim that measuring dispersal in terms of distance-dependent recruitment rates filters out many problems. Using several dispersal rules and several spatial distributions of breeding sites, it is shown that distance-dependent recruitment rate (DDRR) estimates are independent of the spatial distribution of breeding sites and are sensitive to differences in dispersal rules. These simulations were carried out with sample sizes of 200 individuals, which is a number exceeded in many studies. Variation in clumping of breeding sites (colony sizes) also has little effect on the resulting DDRR estimates. The effects of individuals entering and leaving the study area was simulated by assuming that only half the area was observed. Comparing the “observed” movements with the total distribution of distances dispersed shows that the shape of the DDRR is not affected, although the absolute values are, of course, lower. Thus, DDRR estimates will allow us to start studying dispersal behavior independent of the peculiarities of the study area and independent of the distribution of observer effort.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dispersal is an important process in ecology (Johnson and Gaines 1990; Tinbergen 2005). In particular, natal dispersal—the net displacement between site of birth and site of first reproduction—determines the spatial scale of population dynamics and gene flow. In birds, large amounts of data have been collected where individuals have been ringed in the nest and later been identified as breeding birds. Yet the measurement of natal dispersal is quite problematic, because there are almost always important differences in the opportunity to observe movements over different distances (Korner-Nievergelt et al. 2010). This heterogeneity in observability quickly leads to discrepancies between the observed dispersal and the true dispersal distance distribution (Baker et al. 1995; Kendall and Nichols 2004; Koenig et al. 1996; Nichols and Kaiser 1999).

Two of the main problems in this respect are individuals that move out of the study area and are thereby lost from observation (Barrowclough 1978), and the fact that within a study, the distribution of all possibly observed distances varies between locations (van Noordwijk 1984, 1995; Winkler et al. 2005). For example, the maximum distances are longer at the periphery than in the center, and the number of sites at short distances is higher in the center. It has been suggested that this latter problem can be largely circumvented by expressing dispersal as a distance-dependent recruitment rate DDRR, in which observed dispersal movements are expressed relative to the numbers ringed in that distance class (van Noordwijk 2006).

Here the performance of DDRR as a measure of dispersal is studied using simulated data. There are many aspects of measuring dispersal that can be investigated by means of simulations. Birds breed in either more-or-less evenly spaced territories or colonies. Colonial breeding adds complications due to variation in colony sizes. To incorporate these problems, the simulations are performed in terms of breeding colonies. The results presented here are by no means exhaustive, but they illustrate several aspects of the method:

-

1.

There should be a substantial reduction in the variation in results obtained from replicate studies with different distributions of breeding colonies

-

2.

Effects of variation in colony size should be largely eliminated

-

3.

The method should be sensitive to differences in the dispersal rules used

-

4.

Effects of incomplete knowledge due to animals moving into and out of the study area should be largely eliminated from the results

These simulations also show that the resulting DDRRs are easy to interpret because they show the dispersal rules used in the simulation in a direct way.

Methods

Calculation of distance-dependent recruitment rates

The basic data consist of observations on individuals that were born at a known location and initiated reproduction at a known location. For each location where a new breeding bird has settled, it is possible to calculate how many individuals were ringed at each distance during the birth year of the recruits. These data are summarized in distance classes. These distributions of distances to ringing locations are then averaged over all recruits. The resulting distribution describes the average numbers ringed in each distance class, which gives a complete description of what could possibly be observed. Dividing the frequencies of the actually observed number of recruits per distance class by the average numbers ringed per distance class gives the number of recruits observed per nestling ringed: a recruitment rate per distance class; hence DDRR. Formal definitions are given in “Appendix 1” and a step-by-step manual for calculating DDRR on real data is given in “Appendix 2.”

Basic simulations

In each run, 25 points (studied colonies) were generated with coordinates drawn from uniform distributions. Next, 200 individuals were generated that started at one colony and moved to a second colony, according to one of the sets of dispersal rules. The distance between the natal and breeding colony of each individual was then calculated, and these distances were grouped into a frequency distribution that was to be presented as numbers observed. The same data were also analyzed to generate DDRR values. For each recruited individual, all distances to the starting colonies for all individuals in that run were calculated to generate the average number of individuals marked in each distance class. DDRR values are the number of individuals observed per distance class divided by the average number of individuals marked in that distance class. All simulations were performed in PASCAL programs.

Dispersal rules

In all cases, the starting colony for each individual was drawn randomly from the set of colonies. The following dispersal rules were used:

-

1.

Random redistribution. One point was drawn randomly from the total set of colonies. The probability that an individual moved to any colony (including the colony of origin) is thus equal to the reciprocal of the number of colonies.

-

2.

Favoring short distances. Two colonies were drawn at random. The distances from the starting colony were calculated, and the colony with the smallest distance was selected as the destination.

-

3.

Strongly favoring short distances. Similar to 2, but the minimum distance from five randomly picked colonies was used instead of the minimum distance from two colonies.

-

4.

Favoring medium distances. The median distance from three randomly picked colonies was used to determine the destination colony.

Extensions to the simulations

In the real world, colonies are unlikely to have the same size, the biggest colonies may be evenly spaced, and moreover study sites are limited, so that individuals will be lost from sight by moving over the border of the study site. These aspects were included in the analysis by making three further extensions to the simulations. First, colony sizes were made unequal. Instead of 25 colonies of equal size, five colonies were created with a relative size of ten, five with a relative size of five, ten with a relative size of two, and five with a relative size of one. This was achieved by using a list of 100 colonies, but replicating the coordinates as many times as the relative size.

A second extension consisted of fixing the coordinates of the five biggest colonies at [200, 200], [200, 800], [800, 200], [800, 800] and [500, 500] in a field of 1,000 × 1,000, creating an excess of movements of about 430 and 600 units. The other colonies were still located at coordinates drawn randomly from uniform distributions and differed among runs.

The final complication added was that two quarters of the total area were considered to be unobserved. Animals starting and/or finishing in these unobserved areas were included in the “total” dataset but excluded from the “observed” dataset.

Numbers of replicate runs

In all but the final analysis only five runs of the model are presented. This low number was chosen because in real datasets it is often possible to create a number of subsets of the data at this order of magnitude. Since standard errors depend to a large extent on the number of replicates, the standard errors presented here are indicative of what could be obtained with real data. Thus, when differences between dispersal rules are highly significant with these numbers, one can also expect them to be visible in real data. The only exception is the final evaluation of how much better DDRR performs when only partial data are available. Here, 100 runs are presented, which still allows us to show the individual datapoints.

Results

The results for four different dispersal rules are presented in Fig. 1 in the form of means and standard errors over five replicate runs. For random redistribution in the study area, Fig. 1a shows the numbers observed and Fig. 1b shows the corresponding DDRR estimates. Figure 1a illustrates how difficult it is to interpret raw data on dispersal. The numbers observed in the second, third and fourth distance classes are considerably lower than those in the next classes, and numbers rapidly become lower after distance class 13. The first of these two behaviors is due to the relation between distance and area. The area within a distance band increases linearly with the distance, and thus the number of possible destinations increases with distance (see van Noordwijk 1995). The second aspect is due to the fact that, at larger distances, an increasing proportion of the total area at that distance falls outside the study, so there are few observations of individuals moving over longer distances because there are few opportunities to move long distances and be observed (only moving from one edge to the opposite edge).

A comparison of raw data and the resulting DDRR estimates for four dispersal rules. The means and standard errors (SEs) per distance class over five runs are given. In each run, 25 randomly distributed colonies and 200 individuals were generated. a Raw data and b DDRR estimates for random redistribution, c raw data and d DDRR estimates when favoring short distances, e raw data and f DDRR estimates when strongly favoring short distances, and g raw data and h DDRR estimates when favoring intermediate distances

In contrast, the corresponding DDRR estimates (Fig. 1b) are close (within 2 SE) to 1.0 for all distance classes. The dip for the distance classes 2, 3 and 4 is absent, and although the standard errors increase dramatically for the last few distance classes, the results for distance classes 14–20 look interpretable in the DDRR, whereas they are strongly affected by the limitations of the study area in the observed numbers. One final aspect is that, in the observed numbers, the standard errors obtained from replicate simulation runs are high when the numbers observed are high and low in the higher distance classes, whereas in the DDRR the standard errors are high in the last distance classes. This latter pattern corresponds much better to the greater imprecision of the estimates in the higher distance classes, which are based on small numbers.

The easiest way to create a dispersal pattern that is biased towards smaller distances is to draw two random destinations and choose the shortest distance each time (see van Noordwijk 1984). Results are presented in Fig. 1c, d. The raw data are again difficult to interpret. Although the relative dip for distance classes 2 and 3 is smaller than in Fig. 1a, it is still present. In contrast, Fig. 1d shows a gradual decline in DDRR with increasing distance. In this series of runs, the second distance class has a lower value than the first and third, but the difference is only about two SE, instead of five in the corresponding raw data. In Fig. 1e–h, two more dispersal rules are shown, strongly favoring small distances and favoring intermediate distances. In all cases, the DDRR is easily interpretable and peculiar aspects of the raw data have been eliminated.

Unequal colony sizes

Having randomly distributed colonies of equal size is a rather artificial situation; in practice, it is more likely that colony sizes are unequal. With unequal colony sizes (see “Methods”), the standard errors increased in both the raw numbers and the DDRR, but the dispersal rule used is still easily seen in the DDRR (Fig. 2). In the next step, the five big colonies were given fixed, regularly distributed coordinates (see Fig. 3) that were the same in replicate runs. This has the effect that the distances between these colonies will be overrepresented in the raw data (Fig. 4a, c). This effect was not present in the DDRR estimates derived from the same data (Fig. 4b, d).

A comparison of raw data and resulting DDRR estimates for colonies of unequal size. a Raw data and b DDRR estimates for random redistribution, c raw data and d DDRR estimates when favoring short distances. Otherwise similar to Fig. 1

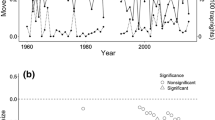

Set-up for “regular” and incomplete observations. The five big colonies are in fixed positions, as indicated, and the coordinates of the other colonies are drawn independently from uniform distributions separately in each run. In the simulations with incomplete observations, all movements starting or ending in the stippled areas are included in the total, but not in the observed dataset

A comparison of two dispersal rules—random redistribution (a, b) and favoring short distances (c, d)—in two different colony layouts with randomly distributed colonies of equal size (continuous blue line) and fixed big colonies with random small colonies (dashed red line). Numbers observed (mean and SE over five runs) are given in a and c, and the resulting DDRR estimates in b and c

Evaluation

How can we measure how much better the DDRR performs than the raw data? There are two things that we want. First, the same dispersal rules in different settings should give us similar results; second, different dispersal rules in the same setting should give us different results. Here we compare the raw data and the corresponding DDRR values for two dispersal rules (random redistribution and favoring short distances) in two settings (randomly distributed colonies of equal size vs. big colonies at fixed locations plus randomly distributed small colonies).

For each distance class, we have a value and a standard error over five runs, which allows us to do a t test for each distance class. This gives us the probability that the two values for the same distance class obtained for the different configurations of the study area come from the same distribution. We can then combine the probabilities for each point using Fisher’s combination test (\( \chi_{{[ 2 {\text{n}}]}}^{ 2} = - 2\Upsigma {\text{ lnP}} \)) to give an overall statement on the similarity of the curves (for the raw data: random redistribution: \( \chi_{[40]}^{2} = 7 2. 5 2 \); P = 0.00125, favoring small distances: \( \chi_{[ 40]}^{ 2} \) = 88.91; P = 0.000014). We can do the same for the DDRR estimates (random redistribution: \( \chi_{[ 3 8]}^{ 2} \) = 28.75; P = 0.86, favoring small distances: \( \chi_{[ 3 8]}^{ 2} \) = 28.74; P = 0.86). Thus, the raw numbers are quite different between the two different colony configurations, but the DDRR measures are very similar for both dispersal rules used. At the same time, the DDRR results were very different for the two dispersal rules (both P < 10−8) in both configurations. Thus, DDRR performed as required.

The effects of partial observations

In practice, study areas are nearly always limited, and thus individuals will move into and out of the study area. The extent to which conclusions are affected by these movements is another aspect to be investigated. This was simulated by limiting the observations to two quarters of the total. Thus, the simulations were carried out as before, but only when both the starting and end points were within the observed part was the individual added to the observations.

One can now compare the total dataset with the observed subset (Fig. 5). Using the setting with the big colonies with fixed coordinates (two of which are now hidden), and favoring short distances as the dispersal rule, the DDRR estimates are proportional, while the raw data have quite differently shaped distributions. The effects of the fixed big colonies are clearly visible in the raw data, and these irregularities have disappeared from the DDRR estimates. It is obvious that the recruitment rates for the observed dataset are lower than those for the full dataset. DDRR estimates are relative measures and not absolute measures. In this case, half the individuals marked at birth disappear out of sight, so that the observed recruitment is half as high (see “Discussion”).

Comparison of the “observed” with the “total” dataset when half the area is hidden from view (see Fig. 3). Means and SEs over five runs using the dispersal rule favoring short distances. a Numbers observed, b corresponding DDRR values

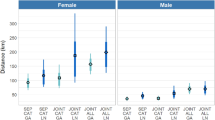

In this case, the performance of DDRR can be evaluated by considering the correlation between the numbers observed per distance class with those in the total data, and to do the same for the DDRR estimates. Figure 6 presents the results for 100 runs. If one excludes DDRR estimates that are based on fewer than five individuals ringed in that distance class, the correlations between the DDRR estimates of the observed subset and the total are quite high (mean 0.90, median 0.93), and higher than for the raw numbers (mean 0.78, median 0.79). We are particularly interested in the quantity 1 − r 2 as a measure of the unexplained variance. Over the 100 runs, this was smaller for the DDRR than for the raw numbers in 93% of the runs [on average 51% (of the 1 − r 2 in the numbers) smaller]. In the few cases where DDRR did not perform better, either the correlation was high for both the raw numbers and the DDRR estimates, or the number of datapoints in the observed set was very low. Thus, DDRR allows us to draw better conclusions about the dispersal behavior when (a substantial) fraction of the movements are unobserved than the raw numbers.

Discussion

The simulations described here demonstrate that DDRR estimates are easier to interpret than raw data. Moreover, changes in the layout of the study have no effect on the resulting DDRR estimates, while different dispersal rules used can easily be distinguished. Furthermore, hiding data from observation has little effect on the shape of the obtained DDRR estimates. DDRR estimates are not absolute numbers: they tell us how recruitment varies with distance. They clearly reach their limits at distances near the size of the area studied.

In calculating DDRR estimates, no assumptions are made about any sort of underlying distribution. The only two assumptions made are that dispersal can be summarized in terms of distances and that averages can be taken over the data. This is equivalent to the assumption that there are no heterogeneities in the dispersal rules used by the birds in space and time. Whenever sufficient data are available, this last assumption can be checked by subdividing the data and checking whether the resulting DDRR values are different.

In situations where it is reasonable to make assumptions about equality of immigration and emigration, one could estimate the proportion of the dispersal process that has been lost from view from the proportion of immigrant first breeders. There are other advantages of studying dispersal in terms of recruitment. Whereas it is not possible to tell where emigrants went to, it is sometimes possible to obtain some information on where immigrants came from, based on isotope ratios in their feathers (Clark et al. 2004; Hobson et al. 2004).

It is an open question as to whether summarizing dispersal in terms of physical distances is the most relevant biologically. For a forest bird, a distance of 1 km over open landscape or over water is probably quite different from the same distance through forest or along hedgerows. In principle, there is no limitation to the different distance measures that could be used when calculating DDRR (Heinz et al. 2005). At present, too little is known about for example the relation between dispersal and density (Kim et al. 2009; Matthysen 2005) to evaluate whether expressing distance in terms of number of territories moved is biologically relevant.

Among the dispersal rules tested in these simulations, it is easy to interpret the resulting DDRR measures. This should facilitate the connection between dispersal patterns observed and the behavior of the individuals moving (Bowler and Benton 2005; Dingemanse et al. 2003; Greenwood 1980; Hawkes 2009; Russell and Rowley 1993).

A first step toward taking the limitations on dispersal observations into account has been to compare the observed movements with a random redistribution of the animals over the observed natal and observed breeding sites (van Noordwijk 1995; Winkler et al. 2005). DDRR estimates are different in a number of ways. Whereas the reference distribution under random redistribution changes if for example the study area is enlarged, DDRR estimates should not change unless the dispersal behavior or the density is different in the added area. The unit of movements observed per nestling ringed at that distance also does not imply any null assumption about dispersal.

The dispersal rules used in these simulations, such as favoring short distances, are not formulated in terms of the actual behavior. In terms of the behavior, two processes can be distinguished. First there is the location, size and shape of the area that an individual is familiar with, which depends on how individuals learn about the world. Second, there is the decision to settle somewhere within this area. The dispersal rules used in the simulations—random redistribution or favoring short distances—are equivalent to familiar areas that are centered around the site of birth but differ in size. The rule of random redistribution implies that individuals move up to the borders of the study area. This could happen either when the study area is smaller than the area with which individuals are familiar, or when the study area is a (habitat) island with reflective boundaries. The dispersal rule of favoring intermediate distances could come about if individuals first move away from the natal site and then have a limited home range. In some cases, this move away from the natal site or part of it may come about before independence, which then leads to correlations in dispersal distances for siblings (Massot et al. 1994; Matthysen et al. 2010). Thus, although the dispersal rules used were formulated in terms of the resulting pattern, there are plausible mechanisms underlying them.

The unit used to describe dispersal is observed recruit per nestling ringed as a function of distance. This unit is easy to understand and should facilitate the incorporation of dispersal into models of populations or metapopulations (Reed and Levine 2005). The interpretability of results in terms of the dispersal rules, the filtering out of specific properties of the study area and the resulting robustness should therefore make DDRR a very attractive way to describe dispersal.

The simulations reported here are by no means exhaustive. They show that DDRR is a step forward in isolating the dispersal behavior from peculiarities of the study area. This should allow us to start analyzing variation in dispersal which is due to biologically interesting processes.

References

Baker M, Nur N, Geupel GR (1995) Correcting biased estimates of dispersal and survival due to limited study area—theory and an application using Wrentits. Condor 97:663–674

Barrowclough GF (1978) Sampling bias in dispersal studies based on a finite area. Bird Band 49:333–341

Bowler DE, Benton TG (2005) Causes and consequences of animal dispersal strategies: relating individual behaviour to spatial dynamics. Biol Rev 80:205–225

Clark RG, Hobson KA, Nichols JD, Bearhop S (2004) Avian dispersal and demography: scaling up to the landscape and beyond. Condor 106:717–719

Dingemanse NJ, Both C, van Noordwijk AJ, Rutten AL, Drent PJ (2003) Natal dispersal and personalities in great tits (Parus major). Proc R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci 270:741–747

Greenwood PJ (1980) Mating systems, philopatry and dispersal in birds and mammals. Anim Behav 28:1140–1162

Hawkes C (2009) Linking movement behaviour, dispersal and population processes: is individual variation a key? J Anim Ecol 78:894–906

Heinz SK, Conradt L, Wissel C, Frank K (2005) Dispersal behaviour in fragmented landscapes: deriving a practical formula for patch accessibility. Landsc Ecol 20:83–99

Hobson KA, Wassenaar LI, Bayne E (2004) Using isotopic variance to detect long-distance dispersal and philopatry in birds: an example with Ovenbirds and American Redstarts. Condor 106:732–743

Johnson ML, Gaines MS (1990) Evolution of dispersal—theoretical models and empirical tests using birds and mammals. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 21:449–480

Kendall WL, Nichols JD (2004) On the estimation of dispersal and movement of birds. Condor 106:720–731

Kim SY, Torres R, Drummond H (2009) Simultaneous positive and negative density-dependent dispersal in a colonial bird species. Ecology 90:230–239

Koenig WD, VanVuren D, Hooge PN (1996) Detectability, philopatry, and the distribution of dispersal distances in vertebrates. Trends Ecol Evol 11:514–517

Korner-Nievergelt F et al (2010) Improving the analysis of movement data from marked individuals through explicit estimation of observer heterogeneity. J Avian Biol 41:8–17

Massot M, Clobert J, Chambon A, Michalakis Y (1994) Vertebrate natal dispersal—the problem of nonindependence of siblings. Oikos 70:172–176

Matthysen E (2005) Density-dependent dispersal in birds and mammals. Ecography 28:403–416

Matthysen E, Van Overveld T, Van de Casteele T, Adriaensen F (2010) Family movements before independence influence natal dispersal in a territorial songbird. Oecologia 162:591–597

Nichols JD, Kaiser A (1999) Quantitative studies of bird movement: a methodological review. Bird Study 46:289–298

Reed JM, Levine SH (2005) A model for behavioral regulation of metapopulation dynamics. Ecol Modell 183:411–423

Russell EM, Rowley I (1993) Philopatry or dispersal—competition for territory vacancies in the splendid fairy-wren, Malurus splendens. Anim Behav 45:519–539

Tinbergen JM (2005) Biased estimates of fitness consequences of brood size manipulation through correlated effects on natal dispersal. J Anim Ecol 74:1112–1120

van Noordwijk AJ (1984) Problems in the analysis of dispersal and a critique on its heritability in the great tit. J Anim Ecol 53:533–544

van Noordwijk AJ (1995) On bias due to observer distribution in the analysis of data on natal dispersal in birds. J Appl Stat 22:683–694

van Noordwijk AJ (2006) Measuring natal dispersal as distance-related recruitment rates. J Ornithol 147:45

Winkler DW et al (2005) The natal dispersal of tree swallows in a continuous mainland environment. J Anim Ecol 74:1080–1090

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge discussions with many people—in particular Stein Saether—over the last decade that led to the formulation of DDRR in its present form, and I thank Pascaline le Gouar for comments on the manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by F. Bairlein.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Formal definitions

Let Ai be the ith (potential) breeding location with coordinates x i and y i. Let Bj be the jth breeding location where N j individuals were marked in year t − 1. B is a subset of A.

Let Ck be the kth breeding location where a recruit was observed in year t. C is a subset of A, and k is the total number of recruits observed.

The distribution of all possible observations is then given by {N j * D jk} for all j and all k.

Let \( {N}_{p} = {\text{Count}}\left\{ {{N}_{j} *{D}_{jk} | {D}_{p} - 1\le {D}_{jk} < {D}_{p} } \right\} \) where D p is the maximum distance of the pth distance class and D 0 = 0. Then N p/k gives the average number of nestlings ringed at distances between D p−1 and D p, measured from the locations where recruits were observed in year t. Let {D} be the set of distances between the site of birth and the site of recruitment for all recruits with known birth locations.

Note 1

It is assumed here that individuals recruit 1 year after birth. The set B should always be taken from the appropriate year.

Note 2

There is a choice of whether to use set C over all recruits irrespective of whether these recruits have a known origin or not, or to alternatively restrict the set to recruits with known origins. This will make a difference (only) when immigrants (recruits with unknown origins) settle in different places from local recruits. This could happen for example when the study area is very large relative to dispersal distances and more immigrants are expected in the periphery.

Note 3

When data are collected over several years, it is recommended that an average distribution weighted by the number of recruits per year should be calculated: N p = (∑ N pt)/∑ k t where N pt and k t are the quantities for year t.

Appendix 2: A step-by-step guide to calculating distance-dependent recruitment rates

Step 1: Ingredients

We need the following data:

-

(a)

A list of all nests where nestlings were ringed, with their coordinates and the numbers ringed at each location. Using UTM coordinates or national grid coordinates makes the calculation of distances a bit easier, but this is not essential.

-

(b)

A list of all locations where recruits (first-time breeders) were observed, with their coordinates. Here one can either use only recruits whose birth locations are known, or recruits with unknown birth locations can also be included. This will make a difference if immigrants settle at different locations from local recruits.

-

(c)

A list with the distances for the observed recruits (i.e., individuals for which both the birth and the recruitment location are known).

Step 2: Calculating distances between all locations

This is the first step in describing all possible observations. For most datasets, one will want to make these calculations separately for each year and the amount of data will then be manageable within a spreadsheet programme. In the example shown in Table 1, the numbers ringed and the coordinates of the nestboxes where birds fledged are given in columns A, B and C, and the coordinates of recruited birds in the next year are given in rows 1 and 2, starting in column E. The distances between each combination of fledging and recruit are given in the cells E4:I15. The formulae for the first three elements on the diagonal are given below the table. Through the use of the dollar sign, a single formula can be copied for the whole table. Cell A1 gives the number of recruits. Finally, cell A16 shows the sum of all nestlings ringed, which can be used to check for calculation errors.

Step 3: Aggregating distances into frequencies per class

Given the distances between all points calculated in the previous step, we should now calculate the frequencies of distances within each distance class. The easiest way of doing this is first to calculate the cumulative numbers, because this requires only one criterion at a time. In Table 2, the criterion applied for each column is given in row 1. For example, in row 4 in Table 1, we find two distances between 300 and 400 m and three distances between 1,000 and 1,500 m. In each case we multiply the frequency by the number ringed from that box (see formulae for cells L4 and M5 below the table). Row 16 gives us the sums in each column. In row 17 we transform the cumulative distribution into numbers per class by subtracting the sum of the previous classes (see the example formula for cell M17) below the table. In row 18, the last step is to divide these total numbers of possible observations by the number of recruits, which gives us the average numbers of nestlings ringed in each distance class averaged over the points where the recruits were observed. One important check is that the sum of these nestling densities (in cell V18) must be equal to the total number of nestlings ringed from cell A16 in Table 1. Errors in copying formulas are easily made, in particular when the size of the table has changed. One advantage of specifying the criteria in row 1 is that it becomes very easy to redo the calculations with different class boundaries.

Step 4: Calculating averages over years

In step 3, we calculated the average densities of nestlings ringed in each distance class relative to the positions where new breeding birds were recruited for one single year, or rather one specific combination with a year of birth and a year of recruiting. We will normally have such data for a number of years, and it is straightforward to calculate the average per distance class over the years. However, there are a number of choices to be made. One choice is the number of different (replicate) estimates we can make; another choice is whether or not to weight the average densities of nestlings ringed by the numbers of recruits whose dispersal distances were observed. When there is little variation in the densities and or the numbers recruited per year, weighted and unweighted averages will give the same results. When there is substantial variation among years, then weighting is a good idea, since the limitations on what can be observed should be related to the observations made.

Step 5: Evaluating the number of classes

If it is possible to make replicate estimates, keeping the variation in densities within each estimate low is a secondary criterion. Most important are the numbers observed in each distance/time period class. Given the number of observations, we can choose a finer resolution either in space (by choosing more distance classes) or in time (by calculating more replicate estimates). As a rule of thumb, I would recommend that the average number of actual observations per class is on average at least five, and that not more than 25% of the cells have less than five observations. Given a spatial scale, the optimal number of replicates can also be determined by searching for the minimum in the standard errors of the recruitment estimates per distance class.

Step 6: Calculating the recruitment rates

The recruitment rates are obtained by dividing the actual number of observations of individuals that have moved a particular distance by the average density of nestlings ringed in that class. The unit is thus observed recruit per nestling ringed.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van Noordwijk, A.J. Measuring dispersal as distance-dependent recruitment rates: testing the performance of DDRR on simulated data. J Ornithol 152 (Suppl 1), 239–249 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-010-0637-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-010-0637-2