Abstract

Breeding birds often give alarm calls when a predator is near the nest. These calls have been proposed to serve as distraction displays for the predator, alerts for a mate conveying information about the presence of a threat, or a warning for nestlings about a potential risk. These functions, however, may not be mutually exclusive. In our study, we assessed if alarm calls uttered by breeding Southern House Wrens, Troglodytes musculus, are made to warn nestlings about risk. If so, we expected that nestlings would reduce overall activity in the nest and that the parents’ call rate would be related to the detectability of the young (e.g., vocalizations). We experimentally elicited parents’ alarm calls and compared nestling behavior before and after giving that stimulus. We found that Southern House Wren nestlings reduced their time spent vocalizing and remained inactive for longer when their parents called. Therefore, nestlings reduced their detectability by decreasing their activity inside the nest when their parents produced alarm calls. On the other hand, parental calling rates were not related to the nestling activity registered in any experimental stage. Therefore, we failed to find reliable results supporting the hypothesis that parent calling is uttered to silence nestlings. These results appear to indicate that alarm calling by breeding birds might fulfill other functions besides alerting nestlings. Future studies of this species are necessary to understand if parents are warning nestlings about a threat when they emit alarm calls.

Zusammenfassung

Brütende Vögel geben häufig Warnrufe ab, wenn sich in der Nähe des Nestes ein Räuber befindet. Es wird angenommen, dass diese Rufe zur Ablenkung für den Räuber, zur Warnung des Brutpartners oder als Warnung der Nestlinge vor einer Gefahrenquelle dienen. Diese Funktionen schließen sich dabei nicht unbedingt gegenseitig aus. In dieser Studie untersuchten wir, ob Warnrufe brütender Südlicher Hauszaunkönige für deren Nestlinge bestimmt waren. In diesem Fall erwarteten wir, dass Nestlinge ihre Aktivität im Nest verringern und dass die Frequenz der elterlichen Warnrufe mit der Erkennbarkeit der Jungen (z. B. durch Lautäußerungen) korreliert. Wir lösten experimentell Warnrufe der Elternvögel aus und verglichen das Verhalten der Nestlinge vor und nach dem Stimulus. Es zeigte sich, dass die Südlichen Zaunkönignestlinge weniger häufig Lautäußerungen von sich gaben und längere Zeit inaktiv waren, wenn die Eltern riefen. Dadurch verringerten die Nestlinge ihre Entdeckungswahrscheinlichkeit im Falle einer Gefahr. Andererseits war die Frequenz der Warnrufe nicht mit der Aktivität der Nestlinge verbunden. Die Ergebnisse unterstützen also nicht eindeutig die Hypothese, dass Eltern rufen, um ihre Jungen zum Schweigen zu bringen. Möglicherweise dienen Warnrufe von Brutvögeln anderen Funktionen außer der Alarmierung von Jungvögeln. Um festzustellen, ob Warnrufe der Eltern die Jungen vor Gefahr warnen sollen, wären weiterführende Studien notwendig.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anderson M, Brunton DH, Hauber ME (2010) Species specificity of grey warbler begging solicitation and alarm calls revealed by nestling responses to playbacks. Anim Behav 79:401–409

Andersson MC, Wiklund G, Rundgren H (1980) Parental defence of offspring: a model and an example. Anim Behav 28:536–542

Bachman GC, Chappell MA (1998) The energetic cost of begging in nestling house wrens. Anim Behav 55:1607–1618

Briskie JV, Martin PR, Martin TE (1999) Nest predation and the evolution of nestling begging calls. Proc R Soc Lond B 266:2153–2159

Burger J, Gochfeld M, Saliva JE, Gochfeld D, Gochfeld D, Morales H (1989) Antipredator behaviour in nesting zenaida doves (Zenaida aurita): parental investment or offspring vulnerability? Behaviour 65:129–143

Caro T (2005) Anti-predator defences in birds and mammals. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Curio E (1987) Brood defence in the great tit: the influence of age, number and quality of young. Ardea 75:33–42

Davies NB, Madden JR, Butchard SHM (2004) Learning fine-tunes a specific response of nestlings to the parental alarm calls of their own species. Proc R Soc Lond B 271:2297–2304

Dearborn DC (1999) Brown-headed cowbird nestling vocalizations and risk of nest predation. Auk 116:448–457

Duckworth JW (1991) Responses of breeding reed warblers Acrocephalus scirpaceus to mounts of sparrowhawk Accipiter nisus, cuckoo Cuculus canorus and jay Garrulus glandarius. Ibis 133:68–74

East M (1981) Alarm calling and parental investment in the robin Erithacus rubecula. Ibis 123:223–230

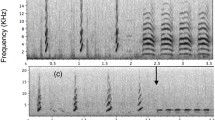

Fasanella M, Fernández GJ (2009) Alarm calls of the southern house wren, Troglodytes musculus: variation with nesting stage and predator model. J Ornithol 150:853–863

Gill SA, Sealy SG (2003) Test of two functions of alarm calls given by yellow warblers during nest defense. Can J Zool 81:1685–1690

Greig-Smith PW (1980) Parental investment in nest defence by stonechats (Saxicola torquata). Anim Behav 28:604–619

Haftorn S (1999) Contexts and possible functions of alarm calling in the willow tit, Parus montanus; the principle of “better safe than sorry”. Behavior 137:437–439

Halupka K (1998) Vocal begging by nestlings and vulnerability to nest predation in meadow pipits Anthus pratensis: to what extent do predation costs of begging exist? Ibis 140:144–149

Haskell DG (1994) Experimental evidence that nestling begging behavior incurs a cost due to nest predation. Proc R Soc Lond B 257:161–164

Haskell DG (1999) The effect of predation on begging-call evolution in nestling wood warblers. Anim Behav 57:893–901

Haskell DG (2002) Begging behaviour and nest predation. In: Wright J, Leonard ML (eds) The evolution of begging: competition, cooperation and communication. Springer, The Netherlands, pp 163–172

Hasson O (1991) Pursuit-deterrent signals: communication between prey and predator. Trends Ecol Evol 6:325–329

Hauser MD (1998) The evolution of communication. MIT Press, Cambridge

Högstedt G (1983) Adaptation unto death: function of fear screams. Am Nat 121:562–570

Hurd CR (1996) Interspecific attraction to the mobbing calls of blackcapped chickadees (Parus atricapillus). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 38:287–292

Kleindorfer S, Hoi H, Fessl B (1996) Alarm calls and chick reactions in the moustached warbler, Acrocephalus melanopogon. Anim Behav 51:1199–1206

Knight RL, Temple SA (1986) Nest defence in the American goldfinch. Anim Behav 34:887–897

Knight RL, Temple SA (1988) Nest-defense behaviour in the red-winged blackbird. Condor 90:193–200

Krams I, Krama T, Igaune K (2006) Alarm calls of wintering great tits Parus major: warning of mate, reciprocal altruism or a message to the predator? J Avian Biol 37:131–136

Laiolo P, Tella JL, Carrete M, Serrano D, López G (2004) Distress calls may honestly signal bird quality to predators. Proc R Soc Lond B 271:513–515

Leavesley AJ, Magrath RD (2005) Communicating about danger: urgency alarm calling in a bird. Anim Behav 70:365–373

Leech SM, Leonard ML (1997) Begging and the risk of predation in nestling birds. Behav Ecol 8:644–646

Lichtenstein G (1997) Begging behaviour and host exploitation in three species of parasitic cowbirds. PhD thesis, Cambridge University

Llambías PE, Fernández GJ (2009) Effects of nestboxes on the breeding biology of southern house wrens Troglodytes aedon bonariae in the southern temperate zone. Ibis 151:113–121

Madden JR, Kilner RM, Davies NB (2005a) Nestling responses to adult food and alarm calls: 1. Species-specific responses in two cowbird hosts. Anim Behav 70:619–627

Madden JR, Kilner RM, Davies NB (2005b) Nestling responses to adult food alarm calls: 2. Cowbirds and red-winged blackbirds reared by eastern phoebe hosts. Anim Behav 70:629–637

Maurer G, Magrath RD, Leonard ML, Horn A, Donnelly C (2003) Begging to differ: scrubwren nestlings beg to alarm calls and vocalize when parents are absent. Anim Behav 65:1045–1055

McDonald PG, Wilson DR, Evans CS (2009) Nestling begging increases predation risk, regardless of spectral characteristics or avian mobbing. Behav Ecol 20:821–829

McGregor PK (1993) Signalling in territorial systems: a context for individual identification, ranging and eavesdropping. Philos Trans R Soc Lond 340:237–244

McGregor PK, Otter K, Peake TM (1999) Communication networks: receiver and signaller perspectives. In: Espmark Y, Amundsen T, Rosenquist G (eds) Animal signals: signalling and signal design in animal communication. Tapir Academic, Trondheim, pp 405–416

Montgomerie RD, Weatherhead PJ (1988) Risks and rewards of nest defense by parent birds. Q Rev Biol 63:167–187

Neudorf DL, Sealy SG (1992) Reactions of four passerine species to threats of predation and cowbird parasitism: enemy recognition or generalized responses? Behaviour 123:84–105

Onnebrink H, Curio E (1991) Brood defense and age of young: a test of the vulnerability hypothesis. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 29:61–68

Ottoni EB (2000) EthoLog 2.2. A tool for the transcription and timing of behaviour observation sessions. Behav Res Meth Instrum Comput 32:446–449

Platzen D, Magrath RD (2004) Parental alarm calls suppress nestling vocalization. Proc R Soc Lond B 271:1271–1276

Platzen D, Magrath RD (2005) Adaptive differences in response to two types of parental alarm call in altricial nestlings. Proc R Soc Lond B 272:1101–1106

Redondo T, Arias de Reyna L (1988) Locatability of begging calls in nestling altricial birds. Anim Behav 36:653–661

Redondo T, Carranza J (1989) Offspring reproductive value and nest defense in the magpie (Pica pica). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 25:369–378

Rohwer S, Frettwell SD, Tuckfield RC (1976) Distress screams as a measure of kinship in birds. Am Midl Nat 96:418–430

Skutch AF (1953) Life history of the southern house wren. Condor 55:121–149

Valone TJ, Templeton JJ (2002) Public information for the assessment of quality: a widespread social phenomenon. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B 357:1549–1557

Weatherhead PJ (1979) Do savannah sparrows commit the concorde fallacy? Behav Ecol Sociobiol 5:373–381

Yasukawa K (1989) The costs and benefits of a vocal signal: the nest-associated ‘chit’ of the female red-winged blackbird, Agelaius phoeniceus. Anim Behav 38:866–874

Young BE (1994) Geographic and seasonal patterns of clutch-size variation in house wrens. Auk 111:545–555

Zahavi A, Zahavi A (1997) The handicap principle. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Acknowledgments

We thank Paulo E. Llambías for the help given in the field, the Whisky-Michelli family and Luis Martinez for allowing us to work on their ranches at Buenos Aires, and Mario Beade for logistical support. We also thank Jose E. Crespo, Craig Barnett, Idrikis Krams and one anonymous reviewer for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. This work was supported by grants to G.J.F. provided by the University of Buenos Aires (Grant X007 and X434) and CONICET Grants (PIP5223). All methods used in the present study meet the ethical requirements for science research and comply with the current laws of our country.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by T. Friedl.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Serra, C., Fernández, G.J. Reduction of nestlings’ vocalizations in response to parental alarm calls in the Southern House Wren, Troglodytes musculus . J Ornithol 152, 331–336 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-010-0595-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-010-0595-8