Abstract

This paper focuses on developing countries’ pioneer exports to the OECD and obtains several important results on export dynamics, linking export experience and export survival. Using product level data at the SITC 5-digit level for 114 developing countries over the 1962–2009 period, we show that prior export experience obtained in non-OECD markets significantly increases survival of pioneer exports toward the OECD. The experience does not need to last long, as gaining experience for more than two years does not confer any additional benefit. The effect of experience depreciates rapidly with time: a break in export experience prior to entering the OECD reduces the advantage on survival. Finally, the role of prior export experience is particularly relevant for survival in the first two years upon entry into the OECD. The geographic dynamic of export experience reveals that experience is acquired in neighboring, easy to access markets before reaching more distant, richer partners and ultimately serving the OECD with a higher probability of survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Developing countries encompass all the non-high-income countries according to the World Bank definition: i.e., all countries with income below $12,196 per capita calculated according to the World Bank Atlas method using 2009 GNI per capita. The definition of OECD used in this paper includes all pre-1973 OECD countries plus Korea, i.e. Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, Japan, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, Spain, Greece, Ireland, Iceland, Korea, Netherland, Norway, New-Zealand, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom and United States.

A pioneer export is defined as the first time a product k is exported from a country i.

For example, producers in the Yacht industry originally focused on MERCOSUR countries before serving developed markets successfully.

Our choice of this specific framework is explained further in Sect. 2.

At the firm level, it would actually be impossible to distinguish the effect of experience on survival from the externality spilling over from the pioneers to other firms.

Note that we not only capture pioneer exports to the OECD but also, for countries that acquire experience at the product level, trace back exports to their first appearance—we capture pioneer exports to the world.

Rauch and Trindade (2002) show that the existence of a Chinese diaspora creates networks that facilitate bilateral trade.

Using our database, we find that, for example, exports of “Fish, fresh, chilled or frozen” to the OECD account for 69% of the Seychelles’ total exports 10 years after entry in the OECD. This statistic is 12% for “Aluminium and aluminium alloys, unwrought” from Ghana or 10% for “Mens and boys outer garments, not knitted” from Belize.

We do not intend to study the role of experience within an OECD country prior to surviving in other OECD markets. This is an interesting question but it is beyond the scope of the present paper.

Introducing uncertainty about export profitability helps reconcile heterogeneous firms models à la Melitz (2003) with the high level of export failure mentioned above and with the fact that many firms do not enter all markets simultaneously, and tend to expand the set of destinations to which they export slowly (Eaton et al. 2008; Albornoz et al. 2012; Artopoulos et al. 2013).

It encompasses domestic paperwork, knowledge of customs procedures, export finance and insurance, banking and international laws, establishment of international marketing office, adaptation to international business practices including good planning and on-time delivery, search for initial distribution networks, as well as the general appeal of the product abroad (i.e., is there any demand for the product in foreign markets).

Developing countries and OECD countries are defined above. We excluded all those countries that did not report exports to the world for at least 10 consecutive years from the sample.

Note that the dimension of our analysis precludes the use of product-country fixed effects as the dependent variable captures duration at the product-country level only for one spell (the first).

The well-known incidental parameter problem limits the number of fixed effects included in the regression.

Linear probability models do not estimate the impact of experience on the duration of a spell per se but on the probability of surviving s years (conditional or not on surviving the year before). Moreover, the model can be biased as the dependent variable is a discrete one with a lot of zeroes (for instance, the unconditional probability of surviving one year is 24.2%, and only 5.6% after 10 years). It is thus a good complement to the non-linear Cox model but does not represent a better alternative for survival analysis.

We also use a more restrictive conditional probability where \(S_{ikt}^{s/n}\) is the probability that a spell survives after s years (e.g., 5 years) conditional on being active n years (e.g., 2 years) after its start. With such a definition, we capture the effect of previous experience on conditional survival, i.e. on the probability that a relationship that has lasted 2 periods will remain active for 5 years. The sample is reduced as all spells that did not last at least 2 years are dropped.

Another source of left-censoring results from the arbitrary start of our database in 1962. We cannot guarantee that a spell starting in 1963 (or later years) is the very first one to the OECD market. Importantly, only 10% of the sub-sample of “first” spells occurs before 1972. The left-censored nature of our data is thus unlikely to affect our result significantly. We further test for the robustness of our result to this type of left-censoring by running our main estimation on the subsample of first spells occurring after 1980 or 1990. Results are unchanged (see Sect. 6.3). In order to explore the dynamic of experience accurately, we also accounted for left-censoring in pre-OECD experience. As for export to the OECD, if the first year of export to any market (where experience is acquired) coincided with the first year of reported trade data, the observation (i.e., the spell) was dropped from the analysis.

For these variables we consider values at the country of entry. For 6% of the spells, pioneers enter the OECD through several countries. In such cases, we consider the weighted average, where weights reflect the size of the spells. The initial value variable stands as an exception for which we use the cumulative value (e.g. the initial value of a spell corresponds to the addition of values in each OECD country of entry). Note that in a previous version of the paper (i.e., Carrere and Strauss-Kahn 2012), these control variables are measured for the OECD as a whole (as an average over all OECD countries). Results are very similar to the ones presented here.

We also tried introducing these variables measured at the country of entry. Results are unchanged and are available upon request.

We tried breaking down the market access variable between reciprocal and non-reciprocal FTAs and found, as expected, that the negative effect of market access on export survival is mainly driven by non-reciprocal FTAs (GSPs). This corroborates the idea that easy access leads to entry of non-performing exporters.

Assuming that competition and market penetration may be regional rather than country-specific, we built measures of competition and market penetration by groups (i.e., North America, Europe and Asia). Results are similar to those with country level variables and are available upon request.

When the RCA variable is omitted, the coefficient on previous experience decreases slightly, suggesting a positive selection bias in the absence of controls for country efficiency.

We also tried dropping the top 10% biggest demand shocks (corresponding to more than 5 exporters of a given product in the same year). Results are unchanged.

The number of observations is drastically reduced when σ is introduced due to data availability and classification conversion (from HS-3 digit to SITC rev. 1–5 digits). Importantly, coefficients on variables are very stable.

For variables that are likely to evolve across time (e.g., GDP, competition and market access), we introduce a growth between period t and t + s in addition to the level of these variables. Our results, available upon request, are unchanged.

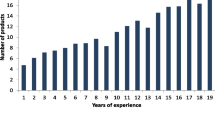

As reported in Table 8, 5 years is the highest number of consecutive years of non-OECD export experience before serving the OECD.

Similarly, Molina (2010) shows a pattern of export dynamic where exports expand from within PTA member countries to non-member countries.

In case of multiple non-OECD partners in t − 1, we use either the mean across partners (i.e., for distance and GDP) or the maximum (i.e., if one partner has a PTA/common border/common language with the OECD country of entry then PTA/common border/common language = 1). Note that the median number of export markets in t − 1 is 1, 3 meaning that a large majority of exporters have only one non-OECD partner in t − 1.

We also introduced these non-OECD characteristics alternatively (instead of jointly) in the regression. Hazard ratios remain non-significantly different from 1.

In order to include importer fixed effects, we need to limit our sample to the export spells which have a single OECD entry partner. This reduces our sample and creates a selection bias.

References

Aeberhardt, R., Buono, I., & Fadinger, H. (2014). Learning and the dynamics of exporting: theory and evidence from French firms. European Economic Review, 68, 219–249.

Akhmetova, Z., & Mitaritonna, C. (2013). A model of firm experimentation under demand uncertainty: An application to multi-destination exporters. (CEPII Working Paper, N°2013-10).

Albornoz, F., Calvo-Pardo, H. F., Corcos, G., & Ornelas, E. (2012). Sequential exporting. Journal of International Economics, 88(1), 17–31.

Albornoz, F., Fanelli, S., & Hallak, J. C. (2016). Survival in export markets. Journal of International Economics, 102, 262–281.

Araujo, L., Mion, G., & Ornelas, E. (2016). Institutions and export dynamics. Journal of International Economics, 98, 2–20.

Artopoulos, A., Friel, D., & Hallak, J. C. (2013). Export emergence of differentiated goods from developing countries: export pioneers and business practices in Argentina. Journal of Development Economics, 105, 19–35.

Banerjee, A. (1992). A simple model of herd behavior quaterly. Journal of Economics, 107(3), 797–817.

Békés, G., & Balázs, M. (2012). Temporary trade and heterogeneous firms. Journal of International Economics, 87(2), 232–246.

Bernard, A., & Jensen, J. (2004). Why some firms export. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(2), 561–569.

Besedeš, T., & Prusa, T. J. (2006a). Ins, outs and the duration of trade. Canadian Journal of Economics, 39(1), 266–295.

Besedeš, T., & Prusa, T. J. (2006b). Product differentiation and duration of US import trade. Journal of International Economics, 70(2), 339–358.

Besedeš, T., & Prusa, T. J. (2011). The role of extensive and intensive margins and export growth. Journal of Development Economics, 96(2), 371–379.

Bikhchandani, S., Hirshleifer, D., & Welch, I. (1998). Learning from the behavior of others: conformity, fads, and informational cascades. Journal of Economic Perspective, 12, 151–170.

Brenton, P., Saborowski, C., & von Uexküll, E. (2010). What explains the low survival rate of developing country export flows. The World Bank Economic Review, 24(3), 474–499.

Broda, C., Greenfield, J., & Weinstein, D. (2006). From groundnuts to globalization: A structural estimate of trade and growth. (NBER Working Paper No. 12512, Sept).

Cadot, O., Carrere, C., & Strauss-Kahn, V. (2014). OECD imports: Diversification of suppliers and quality search. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 150(1), 1–24.

Cadot, O., Iacovone, L., Pierola, D., & Rauch, J. (2013). Success and failure of African exporters. Journal of Development Economics, 101, 284–296.

Carrere, C., & Strauss-Kahn, V. (2012). Exports dynamics: Raising developing countries exports survival through experience. (FERDI WP P35-A, May).

Cox, D. R. (1972). Regression models and life-tables (with discussion). Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 34(2), 187–220.

Defever, F., Heid, B., & Larch, M. (2015). Spatial exporter dynamic. Journal of International Economics, 95(1), 145–156.

Dutt, P., Santacreu, A. M., & Traca, D. A. (2014). The gravity of experience. Mimeo.

Eaton, J., Eslava, M., Jinkins, D., Krizan, C., & Tybout, J. (2015). A search and learning model of export dynamics. (2015 Meeting Papers 1535). Society for Economic Dynamics.

Eaton, J., Eslava, M., Kugler, M., & Tybout, J. (2008). The margins of entry into export markets: Evidence from Colombia. In E. Helpman, D. Marin, & T. Verdier (Eds.), The organization of firms in a global economy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Eaton, J., & Kortum, S. (2002). Technology, geography, and trade. Econometrica, 70(5), 1741–1779.

Evenett, S. & Venables, A. (2002). Export growth in developing countries: Market entry and bilateral trade flows. (Working paper). London School of Economics.

Fernandez, A., & Tang, H. (2014). Learning to export from neighbors. Journal of International Economics, 94, 67–84.

Freund, C., & Pierola, M. (2010). Export entrepreneurs: Evidence from Peru. (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5407).

Fugazza, M., & Molina, A. (2011). On the determinants of export survival. (UNCTAD Blue Series Papers 46). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Görg, H., Kneller, R., & Muraközy, B. (2012). What makes a successful export? Evidence from firm-product-level data. Canadian Journal of Economics, 45(4), 1332–1368.

Hausmann, R., & Rodrik, D. (2003). Economic development and Self-Discovery. Journal of Development Economics, 72, 603–633.

Helpman, E., Melitz, M., & Rubinstein, Y. (2008). Estimating trade flows: Trading partners and trading volumes. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2), 441–487.

Hess, W., & Persson, M. (2012). The duration of trade revisited. Continuous-time vs. discrete-time hazards. Empirical Economics, 43(3), 1083–1107.

Hoff, K. (1997). Bayesian learning in an infant industry model. Journal of International Economics, 43, 409–436.

Jovanovic, B. (1982). Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica, 50(3), 649–670.

Lawless, M. (2013). Marginal distance: Does export experience reduce firm trade costs? Open Economies Review, 24(5), 819–841.

Lederman, D., Olarreaga, M., & Payton, L. (2010). Export promotion agencies: Do they work? Journal of Development Economics, 91, 257–265.

Mayneris, F., & Poncet, S. (2015). Entry on difficult export markets by Chinese domestic firms: The role of foreign export spillover. (World Bank Economic Review). Forthcoming.

Melitz, M. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

Molina, A. (2010). Are preferential agreements stepping stones to other markets? (Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Working Paper 13/2010).

Morales, E., Sheu, G. & Zahler, A. (2014). Gravity and Extended Gravity: Using moment inequalities to estimate a model of export entry. (NBER Working Paper No. 19916, February).

Nguyen, D. X. (2012). Demand uncertainty: Exporting delays and exporting failures. Journal of International Economics, 86(2), 336–344.

Nitsch, V. (2009). Die another day: Duration in German import trade. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 145(1), 133–154.

Ozler, S., Taymaz, E., & Yilmaz, K. (2009). History matters for the export decision: Plant-level evidence from Turkish manufacturing industry. World Development, 37(2), 479–488.

Proudman, J., & Redding, S. (2000). Evolving patterns of international trade. Review of International Economics, 8(3), 373–396.

Rauch, J. E., & Trindade, V. (2002). Ethnic Chinese networks in international trade. Journal of International Economics, 84(1), 116–130.

Rauch, J. E., & Watson, J. (2003). Starting small in an unfamiliar environment. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 21, 1021–1042.

Roberts, M. J., & Tybout, J. R. (1997). The decision to export in Colombia: An empirical model of entry with sunk costs. American Economic Review, 87(4), 545–563.

Segura-Cayuela, R., & Vilarrubia, J. (2008). Uncertainty and entry into export markets. (Bank of Spain Working Paper).

Volpe, C., & Carballo, J. (2008). Survival of new exporters in developing countries: Does it matter how they diversify? (INT Working Paper 04). Inter-American Development Bank.

Wagner, R., & Zahler, A. (2015). New exports from emerging markets: Do followers benefit from pioneers? Journal of Development Economics, 114, 203–223.

World Bank. (2012). Surviving: Pathways to African export sustainability. Washington, DC: The World Bank, Trade division.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Békés Gábor, Tibor Besedeš, Maria Bas, Olivier Cadot, Marco Fugazza and Emanuel Ornelas for helpful discussions. We also thank seminar participants at ETSG 2011, ERWIT 2012, FREIT/LETC 2012 and PSE trade seminar 2012 for useful comments on the previous version of the paper entitled “Exports Dynamics: Raising Developing Countries Exports Survival through Experience”, FERDI WP P35-A, may 2012 as well as participants of GTDW 2015 trade seminar in Geneva and the seminar at FERDI in Clermont-Ferrand in 2015. We are responsible for any remaining errors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2: Description of control variables

The control variables include initial export value (COMTRADE, in current dollars) and exporting country GDP (WDI, in constant 2000US$). Both are introduced in log and are expected to decrease the hazard rate.

We also introduce a variable capturing market access. This variable is constructed using the bilateral database available from the website of Jeffrey Bergstrand (May 2011 version) and includes both reciprocal and non-reciprocal trade agreements.Footnote 35 Market access is a dummy variable which takes a value of 1 if there is a preferential trade agreement (PTA) between the exporter and the OECD country of entry. While preferential access to the OECD market is expected to increase entry, its effect on the hazard rate of exports is unknown, as easier entry does not necessarily guaranty longer survival.

The number of multiple spells existing for a trade relationship is a common variable in the survival literature. It refers to a dummy variable equal to 1 if the first (pioneer) spell is followed by other spell(s) and captures the fact that for trade relationships with multiple spells, the first spell is expected to be shorter. Multiple spells should thus lead to higher hazard rate.

Two additional variables are included in the analysis: The first one, competition, computes the number of non-OECD exporters, other than i, of the same product k to the OECD. It is expected to capture current competition on a specific product and should increase the hazard rate. The second one, market penetration, is the number of products belonging to the same SITC 2 as k exported to the OECD by country i in t. It controls for country i knowledge of the OECD market and is expected to decrease the hazard rate.

“Gravity-type” variables between the exporter and the OECD country of entry such as geographical distance or contiguity, common language and colony (dummy variables taking the value of 1 if such link exists) are from the CEPII and are available at http://www.cepii.fr/anglaisgraph/bdd/gravity.htm.

Balassa’s revealed comparative advantage (RCA) index is defined as:

where \(x_{ikt}\) stands for country i exports of product k in t. The potential issue with this measure is its dependence on country size, as the denominator is a weighted average of the export shares. As an alternative, we follow Proudman and Redding (2000) and compute the denominator as an unweighted mean:

with i′ = [1…N]. This alternative measure is equivalent to normalizing the Balassa index by its cross-sectional mean, neutralizing the country size effect.

About this article

Cite this article

Carrère, C., Strauss-Kahn, V. Export survival and the dynamics of experience. Rev World Econ 153, 271–300 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-017-0277-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-017-0277-1