Abstract

This paper uses a newly available comprehensive panel data set for manufacturing enterprises from 2001 to 2005 to document the first empirical results on the relationship between imports and productivity for Germany, a leading actor on the world market for goods. Furthermore, for the first time the direction of causality in this relationship is investigated systematically by testing for self-selection of more productive firms into importing, and for productivity-enhancing effects of imports (‘learning-by-importing’). We find a positive link between importing and productivity. From an empirical model with fixed enterprise effects that controls for firm size, industry, and unobservable firm heterogeneity we see that the premia for trading internationally are about the same in West and East Germany. Compared to firms that do not trade at all two-way traders do have the highest premia, followed by firms that only export, while firms that only import have the smallest estimated premia. We find evidence for a positive impact of productivity on importing, pointing to self-selection of more productive enterprises into imports, but no clear evidence for the effect of importing on productivity due to learning-by-importing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The literature on the micro-econometrics of imports is growing rapidly. We are grateful for any hints to empirical studies not listed here.

Related papers include Tomiura (2007) who looks at productivity differentials between Japanese firms that export, invest abroad, and contract out manufacturing or processing tasks to other firms overseas; Amiti and Konings (2007) who investigate the productivity effects of tariff reductions on final goods and on imported intermediate inputs in Indonesia; and MacGarvie (2006) who, in a study on patent citations, reports differences in labour productivity between exporters and non-exporters, and non-importers and importers, for a sample of French firms.

For further details, see Vogel and Dittrich (2008).

For a discussion of the difference in export participation see Wagner (2008).

To economize on space results for statistical tests of differences in means (or distributions—see below) are not reported in detailed tables but summarized in the text. Detailed results are available on request.

Note that the levels of labour productivity differ considerably if firms from West and East Germany are compared. This is one reason why all empirical investigations are carried out for the two parts of Germany separately.

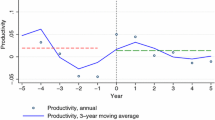

This method has been used to discuss the issue of exports and productivity for the first time by Delgado et al. (2002).

Note that the regression equation specified in (1) is not meant to be an empirical model to explain labour productivity at the firm level; the data set at hand here is not rich enough for such an exercise. Equation (1) is just a vehicle to test for, and estimate the size of, trader premia controlling for other firm characteristics that are in the data set. Furthermore, note that productivity differences at the firm level are notoriously difficult to explain empirically. “At the micro level, productivity remains very much a measure of our ignorance.” (Bartelsman and Doms 2000, p. 586).

Due to limitations concerning the size of main memory available on the computers in the research data centre, it was not possible to estimate the fixed effects model with all West German enterprises. Therefore, the mean number of observations, the mean coefficients, and the mean p-values of five 30% random samples are reported. A documentation of the results for the five random samples can be found in Table 11 in the Appendix.

Matching was done by nearest neighbours propensity score matching. The propensity score was estimated from a probit regression of a dummy variable indicating whether or not a firm is an import starter in 2003 on the log of labour productivity, number of employees, and 3-digit industry dummy variables (all measured in year 2002) plus the rate of growth of labour productivity in the years 2001–2002. The balancing property (that requires an absence of statistically significant differences between the treatment group and the control group in the covariates after matching) is satisfied. The difference in means of the variables used to compute the propensity score were never statistically significant between the starters and the matched non-starters. The common support condition (that requires that the propensity score of a treated observation is neither higher than the maximum nor less than the minimum propensity score of the controls) was imposed by dropping import starters (treated observations) whose propensity score is higher than the maximum or lower than the minimum propensity score of the non-importers (the controls). Matching was done using Stata 10 and the psmatch2 command (version 3.0.0), see Leuven and Sianesi (2003). The results of the probit estimates used in the matching are available on request.

The propensity score was estimated from a probit regression of a dummy variable indicating whether or not a firm is an import starter in t (2003 or 2004 respectively) on the log of labour productivity, number of employees, and 3-digit industry dummy variables (all measured in year t − 1) plus the rate of growth of labour productivity in the years t − 2 to t − 1.

Descriptive mean comparisons as well as OLS estimations of the growth of labour productivity in the above mentioned time periods on import starter dummies confirm the big picture of unclear evidence. The results are available on request.

References

Altomonte, C., & Békés, G. (2008). Trading activities, firms and productivity. Bocconi University, Milan, and Hungarian Academy of Science, Budapest, mimeo, June.

Amiti, M., & Konings, J. (2007). Trade liberalization, intermediate inputs, and productivity: Evidence from Indonesia. American Economic Review, 97(5), 1611–1638. doi:10.1257/aer.97.5.1611.

Andersson, M., Lööf, H., & Johansson, S. (2008). Productivity and international trade—Firm-level evidence from a small open economy. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 144(4), 774–801. doi:10.1007/s10290-008-0169-5.

Bartelsman, E. J., & Doms, M. (2000). Understanding productivity: Lessons from longitudinal micro data. Journal of Economic Literature, XXXVIII(3), 569–594.

Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., Redding, S. J., & Schott, P. K. (2007). Firms in international trade. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(3), 105–130. doi:10.1257/jep.21.3.105.

Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., & Schott, P. K. (2005). Importers, exporters, and multinationals: A portrait of firms in the US that trade goods. (NBER Working Paper Series No. 11404). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bernard, A. B., Eaton, J., Jensen, J. B., & Kortum, S. S. (2003). Plants and productivity in international trade. American Economic Review, 93(4), 1268–1290. doi:10.1257/000282803769206296.

Bernard, A. B., & Wagner, J. (1997). Exports and success in German manufacturing. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 133(1), 134–157.

Castellani, D., Serti, F., & Tomasi, C. (2008). Firms in international trade: importers and exporters heterogeneity in the italian manufacturing industry. University of Perugia, draft mimeo, Jan.

Delgado, M. A., Farinas, J. C., & Ruano, S. (2002). Firm productivity and export markets: A non-parametric approach. Journal of International Economics, 57(2), 397–422. doi:10.1016/S0022-1996(01)00154-4.

Hagemejer, J., & Kolasa, M. (2008). Internationalization and economic performance of enterprises: Evidence from firm-level data. Munich Personal RePEc Archive Paper No. 8720, May.

Halpern, L., Miklós, K., & Szeidl, Á. (2005). Imports and productivity. Institute of Economics, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, mimeo, June.

Heckman, J. J., LaLonde, R. J., & Smith, J. A. (1999). The economics and econometrics of active labor market programs. In O. C. Ashenfelter, & D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 3A, pp. 1865–2097). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Kasahara, H., & Lapham, B. (2008). Productivity and the decision to import and export: Theory and evidence. (CESifo Working Paper No. 2240), March, Journal of International Economics (forthcoming).

Kasahara, H., & Rodrigue, J. (2005). Does the use of imported intermediates increase productivity? Plant-level evidence. (EPRI Working Paper Series No. 2005-7). University of Western Ontario.

Leuven, E., & Sianesi, B. (2003). PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing, http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s432001.html.

Lichtenberg, F. R. (1988). Estimation of the internal adjustment costs model using longitudinal establishment data. Review of Economics and Statistics, 70(3), 421–430. doi:10.2307/1926780.

MacGarvie, M. (2006). Do firms learn from international trade? Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(1), 46–60.

Mayer, T., & Ottaviano, G. I. P. (2008). The happy few: The internationalisation of European firms. New facts based on firm-level evidence. Intereconomics 43(3), 135–148.

Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725. doi:10.1111/1468-0262.00467.

Muuls, M., & Pisu, M. (2007). Imports and exports at the level of the firm: Evidence from Belgium. (CEP Discussion Paper No. 801). London: London School of Economics and Political Science.

Sjöholm, F. (1999). Exports, imports and productivity: Results from Indonesian establishment data. World Development, 27(4), 705–715. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00160-0.

Tomiura, E. (2007). Foreign outsourcing, exporting, and FDI: A productivity comparison at the firm level. Journal of International Economics, 72(1), 113–127. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2006.11.003.

Tucci, A. (2005). Trade, foreign networks and performance: A firm-level analysis for India. (Development Studies Working Papers No. 199). Centro Studi Luca D’Agliano, Turino.

Vogel, A., & Dittrich, S. (2008). The German turnover tax statistics panel. Schmoellers Jahrbuch/Journal of Applied Social Science Studies, 128(4), 661–670.

Wagner, J. (2002). The causal effects of exports on firm size and labor productivity: First Evidence from a matching approach. Economics Letters, 77(2), 287–292. doi:10.1016/S0165-1765(02)00131-3.

Wagner, J. (2007a). Exports and productivity: A survey of the evidence from firm level data. The World Economy, 30(1), 60–82. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2007.00872.x.

Wagner, J. (2007b). Exports and productivity in Germany. Applied Economics Quarterly, 53(4), 353–373.

Wagner, J. (2008). A note on why more West than East German firms export. International Economics and Economic Policy, 5(4), 363–370. doi:10.1007/s10368-008-0119-7.

Acknowledgments

All computations were performed inside the Research Data Centre of the German Federal Statistical Office (Destatis). We thank Tim Hochgürtel for running our Stata do-files and checking the voluminous outputs for any violations of privacy, Stefan Dittrich from Destatis for his invaluable help with the data from the German Turnover Tax Statistics Panel, and an anonymous referee for helpful comments. The enterprise data used in this study are confidential but not exclusive; see Vogel and Dittrich (2008) for details on how to access these data via the Research Data Centre. To facilitate replication and extensions the do-files used in this study are available from the first author on request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Appendix Table 11.

About this article

Cite this article

Vogel, A., Wagner, J. Higher productivity in importing German manufacturing firms: self-selection, learning from importing, or both?. Rev World Econ 145, 641–665 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-009-0031-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-009-0031-4