Abstract

The ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2 (AS2) gene in Arabidopsis thaliana is responsible for the development of flat, symmetric, and extended leaf laminae and their vein systems. AS2 protein is a member of the plant-specific AS2/LOB protein family, which includes 42 members comprising the conserved amino-terminal domain referred to as the AS2/LOB domain, and the variable carboxyl-terminal region. Among the members, AS2 has been most intensively investigated on both genetic and molecular levels. AS2 forms a complex with the myb protein AS1, and is involved in epigenetic repression of the abaxial genes ETTIN/AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR3 (ETT/ARF3), ARF4, and class 1 KNOX homeobox genes. The repressed expression of these genes by AS2 is markedly enhanced by the cooperative action of various modifier genes, some of which encode nucleolar proteins. Further downstream, progression of the cell division cycle in the developing organs is stimulated; meristematic states are suppressed in determinate leaf primordia; and the extension of leaf primordia is induced. AS2 binds the specific sequence in exon 1 of ETT/ARF3 and maintains methylated CpGs in several exons of ETT/ARF3. AS2 forms bodies (designated as AS2 bodies) at nucleolar peripheries. AS2 bodies partially overlap chromocenters, including inactive 45S ribosomal DNA repeats, suggesting the presence of molecular and functional links among AS2, the 45S rDNAs, and the nucleolus to exert the repressive regulation of ETT/ARF3. The AS2/LOB domain is characterized by three subdomains, the zinc finger (ZF) motif, the internally conserved-glycine containing (ICG) region, and the leucine-zipper-like (LZL) region. Each of these subdomains is essential for the formation of AS2 bodies. ICG to LZL are required for nuclear localization, but ZF is not. LZL intrinsically has the potential to be exported to the cytoplasm. In addition to its nuclear function, it has been reported that AS2 plays a positive role in geminivirus infection: its protein BV1 stimulates the expression of AS2 and recruits AS2 to the cytoplasm, which enhances virus infectivity by suppression of cytoplasmic post transcriptional gene silencing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Genetic roles of AS2, AS1, and modifier genes in leaf development

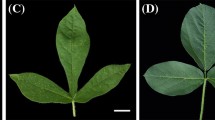

Molecular and genetic analyses of the AS2 gene in Arabidopsis thaliana have shown that it is a key regulator for the development of flat symmetric leaves containing vascular bundles and fine networks of venation systems, the morphology of which seems to be evolved suitably for efficient photosynthesis (Fig. 1a) (Byrne et al. 2000; Ikezaki et al. 2010; Iwakawa et al. 2020; Machida et al. 2015; Ori et al. 2000; Semiarti et al. 2001; Serrano-Cartagena et al. 1999). The as2 mutant generates shorter petioles, leaf lobes, and leaflet-like protrusions from the petioles of leaves in a bilaterally asymmetric manner (Fig. 1a) (Semiarti et al. 2001). The leaf lamina is often plump with a humped, wavy surface and reduced complexity of the leaf venation patterns (Semiarti et al. 2001). Similar abnormalities are observed in leaf lamina of the as1 mutant leaves as well (Candela et al. 1999; Tsukaya and Uchimiya 1997), suggesting that AS2 and AS1 are involved in similar processes to develop flat symmetric and extended leaves and vascular systems consisting of the prominent midvein and complex fine networks of leaf venation. Many mutations that enhance phenotypes of as2 and as1 have been identified (Horiguchi et al. 2011; Ishibashi et al. 2012; Kojima et al. 2011; Luong et al. 2018; Matsumura et al. 2016; Pinon et al. 2008; Ueno et al. 2007; Yao et al. 2008), and see additional references summarized by Machida et al. (2015). We designated the causative genes as “modifiers” for as2 and as1 mutants. Double mutants containing both as2 (or as1) and each of the modifier mutations commonly generate pointed and/or filamentous (rod-shaped) leaves surrounded by abaxialized epidermal cells, in which the development of phloem and xylem cells is not obvious (Ishibashi et al. 2012; Matsumura et al. 2016) (Fig. 1a, b). Genes involved in a wide variety of biological processes (e.g., biogenesis of small RNAs, chromatin modification and remodeling, biogenesis of ribosomes, DNA replication and repair, and formation of proteasomes) have been identified as modifiers (Iwakawa et al. 2020; Machida et al. 2015). Since the details of these mutants have been previously described in the above reviews, we will herein introduce two common features of these mutants. Modifier mutations are characterized as being either weak mutations of an essential gene or mutations in some genes in a family including multiple members. Another interesting feature is that many of the modifier proteins are localized in the nucleus, the nucleolus, and/or accumulated during mitosis of the cell division cycle. These findings imply that AS2 (or AS1) and the modifier proteins might interact cooperatively in the nucleus and/or the nucleolus to be involved in the development of flat symmetric leaves (Fig. 1b), as well as in complex vein systems in leaves. Conventional transcription factors, however, have been excluded from groups of modifiers.

AS2 and AS1 are involved in the development of the flat and symmetrically extended leaf in Arabidopsis. a Leaf phenotypes of wild type (Col-0), the as2-1 single mutant, as2-1, and modifier double mutant (illustrated by Moeko Machida). b Mode of actions of AS2, AS1, and modifier genes on leaf phenotypes

Chemicals that enhance the phenotypes of as2 and as1 single mutants have been also identified. They include two specific inhibiters against histone deacetylases, trichostatin A (TSA) and 4-(dimethylamino)-N-[6-(hydroxyamino)-6-oxohexyl]-benzamide (CAY) (Ueno et al. 2007); berberine (a benzylisoquinoline alkaloid), which acts to bind guanine-rich triplex or quadruplex DNA and possesses various biological activities, as well as has been used in medicines (Nakagawa et al. 2012); and hydroxyurea, a known DNA replication inhibitor (Luong et al. 2018). In addition, by screening for natural compounds that stimulate the formation of filamentous leaves in the as2 background, we have found more compounds that act as modifier mutations (our unpublished observations).

Repressive controls of abaxial-determining ARFs and class 1 KNOXs by AS2 and AS1 are critical for the development of flat symmetric and extended leaves

The AS2 gene was identified and its genetic, molecular, and cellular biological roles in leaf development have been intensively investigated for over 20 years (Iwakawa et al. 2002, 2007, 2020; Machida et al. 2015; Semiarti et al. 2001). Transcription of AS2 starts at the globular stage of embryogenesis, and its transcripts are accumulated in protoderm cells on the adaxial side of cotyledonary primordia at the heart stage (Iwakawa et al. 2002).

As shown in Fig. 2, after germination, the AS2 transcript is only faintly detected in the shoot meristem, and the pattern of its distribution around leaf primordia (P0-P1 stages) is obscure. During development of the primordia of cotyledons and leaves, AS2 expression is detected in epidermal layers of their adaxial domains (P2 stage) (Iwakawa et al. 2007). AS1 transcripts are detected in wide areas in the leaf primordia at very early stages, and distribution of the transcripts focus onto central regions of the leaf primordia, including vascular bundles, as the leaf primordia grow.

Alteration of expression of genes that are involved in abaxial-adaxial patterning during progression of the developmental stages of the leaf in Arabidopsis. P0, P1, and P2 represent the developmental stages of leaf primordia from the earliest P0. In the peripheral zone (PZ) of the shoot apical meristem (SAM) that is characterized by the expression of class 1 KNOX genes (BP, KNAT2, KNAT6), a leaf primordium is born by repressing these KNOX genes. At the early stages (P0-P1), the abaxial-determining genes, such as ARFs, FIL/YAB, and KAN are first expressed. Subsequently, AS2 and AS1 are expressed in the presumptive adaxial domain in the leaf primordium (stage P2), and repress the expression of the abaxial-determining genes, which leads to expression of the adaxial-determining genes, HD-ZIPIIIs, differentiation of the adaxial domain, and establishment of the abaxial-adaxial pattern. The repression of class 1 KNOX genes listed here also plays a role in the extension of leaves

The process of leaf differentiation is initiated by expression of the abaxial-domain determining genes, KANs, FIL/YABs, and ETT/ARF3, in the earliest stages of the leaf primordia (P0 and P1) (Fig. 2). Subsequently, a group of genes including AS2, AS1, and HD-ZIPIIIs are expressed in the presumptive adaxial area in the leaf primordium at the P2 stage to develop the adaxial domain. The expression of AS2 and AS1 is consistently detected during development of young cotyledons and leaves (Iwakawa et al. 2007) to support flat symmetric and extended organs.

As conceptually illustrated in Fig. 3, AS2 and AS1 directly repress the transcription of ETT/ARF3 by binding to its promoter region (Iwasaki et al. 2013), and they also indirectly repress the expression of both ETT/ARF3 and its closely related ARF4 genes by degradation of their ARF transcripts by the RNA silencing mechanism including biogenesis of miR390 and tasiR-ARF (Iwasaki et al. 2013; Takahashi et al. 2013). Phenotypic abnormalities of as2 leaves are restored by the introduction of ett and arf4 mutations, which provide the genetic evidence that AS2 represses the expression of ETT/ARF3 (Iwasaki et al. 2013). Genetic analyses with as2 and as1 mutants imply that suppression of the abaxial genes by AS2 and AS1 in the presumptive adaxial area is critical to ensure differentiation of the adaxial domain in the subsequent step. It might be inevitable for the plant to form balanced adaxial and abaxial domains in order to create a leaf as a flat and symmetrically extended organ. In addition, as described in the first section, it should be worth pointing out that such transcriptional repression of ETT/ARF3 and ARF4 is further achieved by cooperative action with various modifier genes, such as NUC1, RH10, and RID2, the proteins of which are localized to the nucleolus (Matsumura et al. 2016).

AS2 and AS1 also repress the transcription of three class 1 KNOX genes, BREVIPEDICELLUS (BP), KNAT2, and KNAT6 (Fig. 3) (Byrne et al. 2000; Ikezaki et al. 2010; Semiarti et al. 2001) by binding to their respective promoter regions (Guo et al. 2008). This repression results in leaf elongation in the proximal–distal direction (Fig. 2) (Machida et al. 2015; Semiarti et al. 2001).

The AS2 protein is an untypical conventional transcription factor, as described below, and a member of the AS2/LOB protein family that is only present in the plant kingdom. AS1 encodes the myb domain protein. AS2 and AS1 proteins form a complex (AS2-AS1) (Guo et al. 2008; Yang et al. 2008), that represses the transcription of the downstream genes introduced in the next section. AS1 is involved in histone H3 modification, which induces chromatin condensation of the BP gene region to repress the expression of this gene (Li et al. 2016). In addition to this repression system, as described in the following section, we have proposed that AS2-AS1 might be involved in a novel type of epigenetic repressive control of the downstream gene ETT/ARF3 (Iwasaki et al. 2013; Vial-Pradel et al. 2018).

Genes downstream of ARFs and class 1 KNOXs

ETT/ARF3 and ARF4 positively control both the KIP-RELATED PROTEIN 5 (KRP5) gene and the ISOPENTENYL-TRANSFERASE 3 (IPT3) gene (Fig. 3) (Takahashi et al. 2013). Within this entire pathway from the AS2-AS1, the expression of KRP5 and IPT3 could be suppressively controlled. Since KRP5 encodes a CDK inhibitor, a negative regulator of the cell division cycle, AS2-AS1 seems to stimulate the progression of M phase during leaf formation. The repressive control of IPT3, which mediates the biosynthesis of cytokinin, seems to play a critical role in the stabilization of the determinate states of differentiated leaf cells to form flat symmetric leaves.

Repressive control of expression of the gibberellin (GA) biosynthesis gene encoding GA 20-oxidase by the class 1 KNOX gene was first reported with the tobacco plant (Sakamoto et al. 2001). In A. thaliana, AS2-AS1 represses the transcription of three KNOX genes (BP, KNAT2, and KNAT6), but not STM (Semiarti et al. 2001). These three KNOXs redundantly function in repressing transcription of the AtGA20ox1 gene, which is involved in cell elongation and division in leaves (Figs. 2, 3) (Ikezaki et al. 2010).

AS2 is a member of the AS2/LOB protein family and AS2 acts as a single-copy gene

AS2 is a member of the AS2/LOB protein family that consists of 42 predicted proteins in A. thaliana (Fig. 4) (Iwakawa et al. 2002; Shuai et al. 2002), and is the first family member to have its genetic properties associated with its molecular characteristics (Iwakawa et al. 2002; Semiarti et al. 2001). AS2 protein has the AS2/LOB domain in the amino-terminal half (Fig. 4a), the sequence of which is more or less conserved among the family members (Fig. 4b) (Iwakawa et al. 2002; Matsumura et al. 2009). These members, other than AS2, are numbered in order from the one in which the amino acid sequence of the AS2/LOB domain is closest to the sequence of that in the AS2 protein [e.g., the closest member is named AS2-like protein 1 (ASL1 for short)] (Iwakawa et al. 2002). These members are also called Lateral Organ Boundary (LOB) domain (LBD) proteins (Shuai et al. 2002); however, to date, the genetic function of LOB (ASL4) remains unknown. Forty-two members are divided into two classes based on the similarity of the amino acid sequences of the AS2/LOB domains (Fig. 4b), Class I (AS2 and ASL1-ASL35) and Class II (ASL36-ASL41): Class I is further divided into two sub-classes Class Ia (ASL1-ASL28), and Class Ib (ASL29-ASL35).

Characteristic structures of AS2 and AS2/LOB family proteins. a Organization of domains and subdomains in the AS2 protein. NT, ZF, ICG, and LZL represent the N-terminal region, the zinc-finger motif, the internally conserved-glycine region, and the leucine-zipper-like region, respectively. b Comparison of the predicted amino acid sequence of the AS2 domains of AS2 and those of AS2-like proteins (ASLs). Residues that are conserved in all and 41/42 members of the family are colored. Asterisks, dots, and dashes in sequences of family members represent residues identical to those of AS2, different from those of AS2, and gaps, respectively. The AS2 sequence from residue 8 to residue 109 is aligned with those from corresponding sequences of the members (ASLs; see text). According to this nomenclature, members with close numbers have high amino acid sequence identity with each other. Dots and Φ0xxΦ1xxxΦ2xxΦ3xΦ4 above AS2 indicate the position of the hydrophobic residues conserved in LZL. See Sects. 6 and 8 in text

Figure 5 shows the phylogenetic tree of the AS2/LOB protein family of A. thaliana, a modification of the tree of the AS2 family previously reported (Iwakawa et al. 2002). Two types of nomenclature (ASLs and LBDs) are listed side by side and such nomenclature with ASLs should be advantageous for discussing relationships between the phylogeny and developmental functions of members in the AS2/LOB protein family. For example, at least four known proteins involved in auxin-induced lateral root formation are named ASL18/LBD16, ASL16/LBD29, ASL20/LBD18, and ASL24/LBD33; ASL15/LBD17 is also proposed to play a similar role (Berckmans et al. 2011; Goh et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2009; Okushima et al. 2007). All of them are located in the close clades of sub-class Class Ia in the phylogenetic tree. During pollen development, ASL1/LBD36, ASL2/LBD10, and ASL3/LBD25, all of which belong to the close narrow clades of the tree, control asymmetric cell division during pollen development (Kim et al. 2015, 2016). Interestingly, another set of ASL members (SCP/ASL29/LBD27 and ASL30/LBD22 in a small clade) are also involved in the same single process, but at different steps during the progression of pollen development (Kim et al. 2015, 2016; Oh et al. 2010). Note that ASL1/LBD36, ASL2/LBD10, and ASL3/LBD25 belong to Class Ia, and that SCP/ASL29/LBD27 and ASL30/LBD22 belong to Class Ib. Use of the ASL nomenclature might provide an edge to discussion of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) of the AS2/LOB family.

The panel was reproduced and modified from a previous report (Iwakawa et al. 2002)

An unrooted maximum-likelihood tree for 42 members of the AS2/LOB family of proteins from Arabidopsis, as generated by a local rearrangement search. Numbers on branches represent local bootstrap values, which were calculated with the ProtML program. The length of each horizontal branch is proportional to the estimated evolutionary distance. The brackets on the right indicate the classification of members of the AS2/LOB family as shown in Fig. 4b. The NJdist and ProML programs in MOLPHY package version 2.3b3 were used (https://www.ism.ac.jp/ismlib/eng/ismlib/softother.html#molphy).

The AS2/LOB domain consists of three subdomains [the zinc-finger (ZF) motif, the internally conserved-glycine (ICG) region, and the leucine-zipper-like (LZL) region]. The ZF motifs in all members have four perfectly conserved cysteine residues (at positions 10, 13, 20, and 24, in AS2), although limited sequence divergences are found among these cysteine residues. The ZF motif of AS2 is essential for binding to the specific DNA sequence in the downstream target ETT/ARF3 genome as described in the next section (Vial-Pradel et al. 2018). In other subdomains, three amino acid residues are completely, or nearly completely, conserved in all of the family members. In the ICG regions, the glycine residues (at position 46 in AS2) are conserved among all members. The LZL regions are considered to be involved in protein–protein interactions to form homo and/or hetero multimers. The proline residues (at position 80 in AS2) at the border between the ICG and LZL regions are conserved in all members. Interestingly, the glycine residue (at position 83 in AS2) is conserved in 41 members, other than ASL28/LBD26, out of 42. These perfectly conserved residues might play common roles in molecular functions as proteins of the AS2/LOB family. There are also amino-terminal regions (designated NTs) that are variable in length among these members, although little is known about their roles (Luo et al. 2012; Matsumura et al. 2009).

A comparison of deduced amino acid sequences of carboxy-terminal halves in the family members shows that no member exhibits a significant similarity to that of AS2 (Fig. 6) (Matsumura et al. 2009). Since the as2-4 allele had a frame shift mutation in this region (Iwakawa et al. 2002), and the phenotype due to this allele is similar to those due to other as2 alleles (Semiarti et al. 2001), it seems that the C-terminal half is essential for the functions of AS2. The domain swapping experiment between AS2 and each of ASL1, ASL2, and ASL3, the closest members of AS2, has shown that the AS2/LOB domain of AS2 cannot be replaced by those of these closest members, revealing that a few dissimilarities among amino acid residues in the AS2/LOB domain of AS2 and those of these members are critical for the functions of AS2 in leaf development (Matsumura et al. 2009). These sequence analyses and experimental results suggest that AS2 acts as a single-copy gene from the viewpoint of leaf morphogenesis in A. thaliana.

Comparison of the amino acid sequences of the C-terminal halves of predicted proteins of the AS2/LOB family. Each number indicates the identity, as a percentage, between the predicted amino acid sequences of indicated proteins. Percentages greater than 20% are indicated and those less than 20% are marked with −. Percentages greater than 35% are shaded. Numbers in percentages under group designations indicate the identities between entire amino acid sequences, showing that two members in each group have high similarity in entire amino acid sequences. These analyses show that close numbers in ASLs indicate sequence similarities

AS2 protein binds exon 1 of ARF3 and maintains methylated CpGs in other exons

The AS2 protein binds to synthetic double-stranded DNAs containing the sequence GCGGCG as the core motif (Husbands et al. 2007). AS2 forms an immuno-complex with ETT/ARF3 genomic DNA covering its exon 1 (Iwasaki et al. 2013), which includes the CGCCGC/GCGGCG sequence. Our in vitro binding experiments have shown that the AS2 protein binds to the DNA segment in exon 1 of the ETT/ARF3 gene, and that the CGCCGC sequence is critical, but not sufficient, for that binding (Vial-Pradel et al. 2018). The AS2/LOB domain is sufficient for the binding to the DNA segment, and its ZF motif plays an essential role in that binding.

Genome-wide methylome analysis shows that CpG dinucleotides in exons 6, 9, and 10 in the ETT/ARF3 locus are methylated in the Col-0 plant (Cokus et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2006). Exon 6 contains six CpGs, which are highly methylated depending on METHYLTRANSFERASE1, an Arabidopsis ortholog of the vertebrate DNMT1, and AS2 and AS1 are involved in the maintenance of these methylated CpGs (Iwasaki et al. 2013). The presence of the ZF motif in AS2 would be reminiscent of the CxxC-type zinc finger in DNMT1. Modifier genes such as NUC1 and RH10, mentioned in Sect. 2 (Figs. 1, 3), are also involved in the maintenance of the methylation state of CpG in exon 6 (Vial-Pradel et al. 2018). These modifier genes encode nucleolar proteins (Kojima et al. 2007; Matsumura et al. 2016; Petricka and Nelson, 2007; Pontvianne et al. 2007). These results imply that the maintenance of CpG methylation by AS2-AS1 might be related to the cooperative repression of ETT/ARF3 expression with these nucleolar modifier proteins.

Roles of the molecular events mediated by AS2-AS1 and nucleolar proteins in the repressive control of the ETT/ARF3 gene need to be experimentally investigated.

AS2 forms perinucleolar bodies in interphase cells that partially overlap with chromocenters containing rDNA repeats

By using the estradiol-inducible expression system for AS2-fused yellow fluorescence protein (AS2-YFP), we investigated the subcellular localization of the AS2 protein in cells of a transgenic Arabidopsis plant and cultured cell lines of Arabidopsis and tobacco. We reported that AS2 forms granules (designated as AS2 bodies) at the periphery of the nucleolus in interphase cells in the epidermis of the adaxial domains of cotyledonary and leaf primordia (Figs. 7a, 8), although some amounts of AS2-YFP are present in the nucleoplasm of these cells (Luo et al. 2012; Ueno et al. 2007). As illustrated in Fig. 7b, AS2 bodies are variable in shape and size; appear to be rough spheres or beans; and themselves also appear as aggregates of smaller particles. They are, however, not completely random in wild type A. thaliana (Col-0), although fine morphological and quantitative analyses have yet to be performed. The average number of AS2 bodies is calculated to be approximately 1.9 per YFP-positive interphase cell in leaf primordia of the wild-type plant of A. thaliana Col-0 (Luo et al. 2020).

AS2 bodies at the periphery of the nucleolus in the interphase cell of the leaf primordium, where chromocenters containing 45S rDNA repeats are localized. a Two AS2 bodies are visible by fluorescence due to YFP (yellow fluorescent protein) at the periphery of the nucleolus in cells of the leaf primordium of the AS2-YFP-transformed Arabidopsis. The dark area corresponds to the nucleolus (reproduced from Ueno et al. 2007). b Schematic image of the AS2 bodies (yellow) and chromocenters (blue). It has been reported that interphase nuclei from cells of Arabidopsis contain up to 10 chromocenters, which locate near the nuclear periphery and the nucleolus (Fransz et al. 2002). Only several chromocenters were, however, usually visible in an optical section under single focuses by our observations. See the top panel in Fig. 8. c Indicated subdomains (see Fig. 4a) were deleted in these mutant proteins. Subscripts represent positions of deleted amino acid residues in the mutants. Mutant proteins were fused to YFP. These fused constructs were tested for abilities to form AS2 bodies. Patterns of subcellular localization and abilities of fused constructs to complement as2-1 phenotypes were also examined. Panels a and c were reproduced and modified from references by Ueno et al. (2007) and Luo et al. (2020), respectively

modified from a previous report (Luo et al. 2020). Bars = 5 µm

AS2 bodies exhibit dynamic movement during the M phase progression of cells in leaf primordia. Patterns of subcellular localization of AS2-YFP proteins (yellow) were observed in epidermal cells of the adaxial domain in leaf primordia of the transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Nuclei and chromosomes were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (cyan). Under a single focus, one AS2 body is often observed in most single cells undergoing prophase to metaphase of M phase, although the average number of the bodies in a cell during interphase is approximately 1.9 (see Text). Anaphase bridge-like structures are visualized during the progression from anaphase to telophase. Panels were reproduced and

The experiment with the glucocorticoids receptor (GR)-fused AS2 and dexamethasone shows that the migration of AS2 into the nucleus is essential for its role in leaf development (Ueno et al. 2007). It is, however, difficult to identify clearly the nuclear localization signal (NLS) in the AS2 sequence. Although the RRK sequence in the ZF motif (Fig. 4a, b) is proposed to function in nuclear localization (Chen et al. 2019), our result (Fig. 7c) shows that the deletion construct NT-ZF2-24 is not a formed AS2 body, but is localized to the nucleus, showing that the RRK cluster is not involved in the nuclear localization of AS2, and that the ICG and the LZL regions encompassing 85 amino acid residues are sufficient for the nuclear localization. An obvious NLS sequence is, however, absent from these regions, suggesting the involvement of a certain unidentified mechanism in the nuclear localization of AS2.

As shown in Figs. 7b and 8, AS2 bodies overlap partially with the chromocenters, distinct chromatin structures that consist of condensed heterochromatins containing repeats of the ribosomal DNA (45S rDNA encoding 18S, 5.8S, and 28S rRNAs) (Luo et al. 2020). In the diploid genome of A. thaliana (Col-0), there are approximately 1500 copies of the 45S rDNA gene on chromosomes 2 and 4, which exist as tandemly repeated sequences on each of the chromosomes (Copenhaver and Pikaard, 1996) . Two chromocenters corresponding to chromosome 4 in a diploid cell are detected at the periphery of the nucleolus, in which the 45S rDNA genes should be transcriptionally inactive (Pontvianne et al. 2010). The observation that AS2 bodies are overlapped with two nucleolar chromocenters in A. thaliana (Col-0) (Luo et al. 2020) predicts that a role of AS2 bodies might be related to the repressive regulation of ETT/ARF3, such as the inactivation of the 45S rDNA genes in the chromocenters. As mentioned in Sect. 5, AS2 binds to exon 1 of the ETT/ARF3 gene and is involved in the maintenance of gene body methylation in its exon 6. These molecular events might also be involved in the repressive regulation of the gene expression at the nucleolar periphery.

The AS2/LOB domain, which is essential for binding to ETT/ARF3, is necessary and sufficient for the formation of AS2 bodies. We tested deletion mutants of the NT2-9, NT-ZF2-24, ICG25-80, and LZL81-109 regions (Fig. 4a) for their abilities to form AS2 bodies, to control subcellular localization, and to complement the mutant phenotype of as2-1 (Fig. 7c). Results of those experiments showed that deletion constructs without one of the NT-ZF2-24, ICG25-80, and LZL81-109 regions are inactive to form AS2 bodies. Therefore, all of the ZF10-24 motif, ICG25-80, and LZL81-109 regions are essential for the formation of AS2 bodies. The finding that the NT-ZF2-24 deletion is localized to the nucleoplasm suggests that the ZF motif, which is essential for the binding to exon 1 of ETT/ARF3, is not responsible for the nuclear localization of AS2, but that it participates in the perinucleolar localization of AS2 and/or in the formation of AS2 bodies. It is likely that the LZL region is involved in interactions with AS2’s own proteins and/or other associating molecules. In addition, none of the mutants that did not form AS2 bodies could recover the as2-1 phenotype. These results indicate that the formation of AS2 bodies is tightly correlated with the functioning of AS2 in normal leaf development (Luo et al. 2020).

The observation that the deletion construct ICG25-80 is exclusively localized to cytoplasm (Fig. 7c) was unexpected. The deletion construct LZL81-109 is detected in both the nucleoplasm and the cytoplasm, a localization pattern similar to that of the YFP protein, itself. These observations imply that signal(s) controlling nuclear localizations of AS2 might be present in the region covering both ICG and LZL. Interestingly, the LZL region includes the ISLLQHQLRQLQI sequence in residues from 88 to 100 (Fig. 4b), which closely resembles the Φ0xxΦ1xxxΦ2xxΦ3xΦ4 (Φ: hydrophobic residues) sequence proposed as the traditional consensus pattern for the nuclear export signal (NES) (Fung et al. 2015; Luo et al. 2020). The LZL region might function in exporting AS2 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. The ICG region (residues 25–80) might play an inhibitory role by interacting with LZL in exporting AS2 to the cytoplasm. Similar Φ-rich sequences corresponding to the region from Φ0 to Φ3 are present in 23 (ASLs1-11, ASLs15-19, and ASLs21-27) out of 28 members of the class 1a subclass (Fig. 4b) (Iwakawa et al. 2002; Matsumura et al. 2009). Sequences similar to the Φ0xxΦ1xxxΦ2 consensus pattern are also found in the LZL region of Class Ib; however, sequences similar to these are not present in class II.

It would also be interesting to point out that the mutation of NUCLEOLIN1 (nuc1) affects the number and distribution patterns of AS2 bodies in the nucleolus (Luo et al. 2020). The number of AS2 bodies is elevated: smaller sized bodies are found; and some bodies did not co-localize with the perinucleolar chromocenters.

Since NUC1 is one of the abundant proteins in the nucleolus and is involved in various molecular events, such as the processing of rRNA precursors, both the formation and the maintenance of AS2 bodies is presumed to be under the control of the global molecular architecture and interactions within the nucleus.

AS2 bodies are consistently observed in mitotic cells

In addition to interphase cells (uppermost panel of Fig. 8), we examined AS2 bodies during the M phase of the cell cycle in leaf primordial cells of A. thaliana plants, its cultured cell line MM2d (Luo et al. 2020), and tobacco cell line BY2 (Luo et al. 2012). One of the characteristic features of AS2 bodies in relationship to the cell cycle is that they are also observed after the disappearance of the nuclear membrane and the nucleoli as well as the condensation of chromosomes in the process of M phase progression of the cell cycle. In the present article, we briefly introduce the behavior of AS2 bodies during progression of the mitotic phase of cells in leaf primordia (lower panels of Fig. 8). AS2 bodies are observed around condensed chromosomes at prophase and metaphase, after which each body splits into two bodies at anaphase, and they segregate into daughter cells with the separation of chromosomes. An anaphase-bridge-like structure (bottom panel), which resembles ultrafine DNA bridges containing rDNA repeats reported in animal cells (Liu et al. 2014; Nielsen and Hickson, 2016), is visible between two separating AS2 bodies. These results imply that AS2 bodies might also play a role in the segregation of daughter chromosomes after metaphase of the cell cycle in addition to the repressive regulation of ETT/ARF3 by AS2.

A role of AS2 in virus pathogenicity in plants

It has been reported that AS1 and AS2 might play roles in the occurrence of infectious symptoms by plant viruses. βC1 protein, the pathogenicity factor of TYLCCNV (tomato yellow leaf curl china virus), interacts with AS1 protein to develop the infectious symptoms and the disease symptoms of virus-infected plants resembling the phenotypes of plants overexpressing AS2 (Yang et al. 2008). Ye et al. (2015) also reported that the pathogenesis-related protein BV1 encoded by Cabbage leaf curl Virus (CaLCuV), a model for bipartite geminivirus, interacts with AS2, which is recruited to cytoplasm from the nucleus and exerts pressure on AS2 to play a novel role that favors viral infections. BV1 induces expression of the AS2 gene by binding to its promoter even in mature plant leaves, in which AS2 is silent, and the newly synthesized AS2 protein is first imported into the nucleus and then exported to the cytoplasmic granules, P bodies. In P bodies, AS2 interacts with one of its constituents, DCP2 (mRNA-decapping enzyme 2), to promote its decapping activity, decrease the levels of siRNAs, and attenuate PTGS (post transcriptional gene silencing), which is an endogenous critical gene repression system. In addition, overexpression of AS2 in plants (A. thaliana and N. benthamiana) increases the susceptibility of plants to geminivirus infection. On the other hand, the as2 mutant showed improved virus resistance. These observations are consistent with the hypothesis that PTGS acts as an important defense strategy for plants that attack the virus: the finding in the report is simply that AS2 is hijacked by BV1 in the nucleus, even in the mature leaves, is transported to the cytoplasm by the action of BV1, and contributes to the weakening of the defense network called PTGS. How AS2 could elevate the decapping activity of DCP2 by its binding in the P bodies, however, has yet to be investigated.

As we mentioned in Sect. 6 and Fig. 7c, the as2 mutant protein (delta ICG25-80) exclusively accumulates in the cytoplasm (Luo et al. 2020), and the LZL region contains the NES-like sequence (Fig. 4). This observation allows us to predict the possibility that the LZL region might play a role in localization of AS2 to the cytoplasm under certain cellular conditions. BV1 of the geminivirus might bind to the ICG region of AS2 in the nucleus to enhance the action of a putative plant exportin to the proposed NES-like sequence in LZL, which might allow AS2 to be exported to the cytoplasm.

The studies in this section are good examples to show that plant proteins may interact with proteins derived from pathogenic microorganisms to acquire a variety of previously unknown functions. Such invisible properties of molecules might have been born through the evolution of interactions between organisms. Behind molecular interactions, many other proteins in host plants might also gain functions that have yet to be unveiled. Research on pathogenic proteins may lead to the manifestation of the hidden properties of such proteins in host cells. Interestingly, the leaf morphology of some bred vegetables belonging to the Brassica plants resembles the leaf phenotypes of as2 mutants of A. thaliana (Col-0). In the process of vegetable breeding, genetic backgrounds of being resistant to viral infections might have spread through these plants, some of which might carry mutations in AS2 and/or related members of the family.

References

Berckmans B, Vassileva V, Schmid SP, Maes S, Parizot B, Naramoto S, Magyar Z, Alvim Kamei CL, Koncz C, Bögre L, Persiau G, De Jaeger G, Friml J, Simon R, Beeckman T, De Veylder L (2011) Auxin-dependent cell cycle reactivation through transcriptional regulation of Arabidopsis E2Fa by lateral organ boundary proteins. Plant Cell 23:3671–3683

Byrne ME, Barley R, Curtis M, Arroyo JM, Dunham M, Hudson A, Martienssen RA (2000) Asymmetric leaves1 mediates leaf patterning and stem cell function in Arabidopsis. Nature 408:967–971

Candela H, Martínez-Laborda A, Micol JL (1999) Venation pattern formation in Arabidopsis thaliana vegetative leaves. Dev Biol 205:205–216

Chen WF, Wei XB, Rety S, Huang LY, Liu NN, Dou SX, Xi XG (2019) Structural analysis reveals a “molecular calipers” mechanism for a LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN transcription factor protein from wheat. J Biol Chem 294:142–156

Cokus SJ, Feng S, Zhang X, Chen Z, Merriman B, Haudenschild CD, Pradhan S, Nelson SF, Pellegrini M, Jacobsen SE (2008) Shotgun bisulphite sequencing of the Arabidopsis genome reveals DNA methylation patterning. Nature 452:215–219

Copenhaver GP, Pikaard CS (1996) RFLP and physical mapping with an rDNA-specific endonuclease reveals that nucleolus organizer regions of Arabidopsis thaliana adjoin the telomeres on chromosomes 2 and 4. Plant J 9:259–272

Fransz P, De Jong JH, Lysak M, Castiglione MR, Schubert I (2002) Interphase chromosomes in Arabidopsis are organized as well defined chromocenters from which euchromatin loops emanate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:14584–14589

Fung HYJ, Fu SC, Brautigam CA, Chook YM (2015) Structural determinants of nuclear export signal orientation in binding to exportin CRM1. eLife 4:e10034

Goh T, Joi S, Mimura T, Fukaki H (2012) The establishment of asymmetry in Arabidopsis lateral root founder cells is regulated by LBD16/ASL18 and related LBD/ASL proteins. Development 139:883–893

Guo M, Thomas J, Collins G, Timmermans MC (2008) Direct repression of KNOX loci by the ASYMMETRIC LEAVES1 complex of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20:48–58

Horiguchi G, Mollá-Morales A, Pérez-Pérez JM, Kojima K, Robles P, Ponce MR, Micol JL, Tsukaya H (2011) Differential contributions of ribosomal protein genes to Arabidopsis thaliana leaf development. Plant J 65:724–736

Husbands A, Bell EM, Shuai B, Smith HM, Springer PS (2007) LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES defines a new family of DNA-binding transcription factors and can interact with specific bHLH proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 35:6663–6671

Ikezaki M, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Kojima S, Ueno Y, Machida C, Machida Y (2010) Genetic networks regulated by ASYMMETRIC LEAVES1 (AS1) and AS2 in leaf development in Arabidopsis thaliana: KNOX genes control five morphological events. Plant J 61:70–82

Ishibashi N, Kanamaru K, Ueno Y, Kojima S, Kobayashi T, Machida C, Machida Y (2012) ASYMMETRIC-LEAVES2 and an ortholog of eukaryotic NudC domain proteins repress expression of AUXIN-RESPONSE-FACTOR and class 1 KNOX homeobox genes for development of flat symmetric leaves in Arabidopsis. Biol Open 1:197–207

Iwakawa H, Ueno Y, Semiarti E, Onouchi H, Kojima S, Tsukaya H, Hasebe M, Soma T, Ikezaki M, Machida C, Machida Y (2002) The ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana, required for formation of a symmetric flat leaf lamina, encodes a member of a novel family of proteins characterized by cysteine repeats and a leucine zipper. Plant Cell Physiol 43:467–478

Iwakawa H, Iwasaki M, Kojima S, Ueno Y, Soma T, Tanaka H, Semiarti E, Machida Y, Machida C (2007) Expression of the ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2 gene in the adaxial domain of Arabidopsis leaves represses cell proliferation in this domain and is critical for the development of properly expanded leaves. Plant J 51:173–184

Iwakawa H, Takahashi H, Machida Y, Machida C (2020) Roles of ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2 (AS2) and nucleolar proteins in the adaxial-abaxial polarity specification at the perinucleolar region in Arabidopsis. Int J Mol Sci 21:7314

Iwasaki M, Takahashi H, Iwakawa H, Nakagawa A, Ishikawa T, Tanaka H, Matsumura Y, Pekker I, Eshed Y, Vial-Pradel S, Ito T, Watanabe Y, Ueno Y, Fukazawa H, Kojima S, Machida Y, Machida C (2013) Dual regulation of ETTIN (ARF3) gene expression by AS1-AS2, which maintains the DNA methylation level, is involved in stabilization of leaf adaxial-abaxial partitioning in Arabidopsis. Development 140:1958–1969

Kim MJ, Kim M, Lee MR, Park SK, Kim J (2015) LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN (LBD)10 interacts with SIDECAR POLLEN/LBD27 to control pollen development in Arabidopsis. Plant J 81:794–809

Kim M, Kim MJ, Pandey S, Kim J (2016) Expression and protein interaction analyses reveal combinatorial interactions of LBD transcription factors during Arabidopsis pollen development. Plant Cell Physiol 57:2291–2299

Kojima H, Suzuki T, Kato T, Enomoto K, Sato S, Tabata S, Sáez-Vasquez J, Echeverría M, Nakagawa T, Ishiguro S, Nakamura K (2007) Sugar-inducible expression of the nucleolin-1 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana and its role in ribosome synthesis, growth and development. Plant J 49:1053–1063

Kojima S, Iwasaki M, Takahashi H, Imai T, Matsumura Y, Fleury D, Van Lijsebettens M, Machida Y, Machida C (2011) Asymmetric leaves2 and Elongator, a histone acetyltransferase complex, mediate the establishment of polarity in leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 52:1259–1273

Lee HW, Kim NY, Lee DJ, Kim J (2009) LBD18/ASL20 regulates lateral root formation in combination with LBD16/ASL18 downstream of ARF7 and ARF19 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 151:1377–1389

Li Z, Li B, Liu J, Guo Z, Liu Y, Li Y, Shen WH, Huang Y, Huang H, Zhang Y, Dong A (2016) Transcription factors AS1 and AS2 interact with LHP1 to repress KNOX genes in Arabidopsis. J Integr Plant Biol 58:959–970

Liu Y, Nielsen CF, Yao Q, Hickson ID (2014) The origins and processing of ultra fine anaphase DNA bridges. Curr Opin Genet Dev 26:1–5

Luo L, Ando S, Sasabe M, Machida C, Kurihara D, Higashiyama T, Machida Y (2012) Arabidopsis ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2 protein required for leaf morphogenesis consistently forms speckles during mitosis of tobacco BY-2 cells via signals in its specific sequence. J Plant Res 125:661–668

Luo L, Ando S, Sakamoto Y, Suzuki T, Takahashi H, Ishibashi N, Kojima S, Kurihara D, Higashiyama T, Yamamoto KT, Matsunaga S, Machida C, Sasabe M, Machida Y (2020) The formation of perinucleolar bodies is important for normal leaf development and requires the zinc-finger DNA-binding motif in Arabidopsis ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2. Plant J 101:1118–1134

Luong TQ, Keta S, Asai T, Kojima S, Nakagawa A, Micol JL, Xia S, Machida Y, Machida C (2018) A genetic link between epigenetic repressor AS1-AS2 and DNA replication factors in establishment of adaxial-abaxial leaf polarity of. Plant Biotechnol (tokyo) 35:39–49

Machida C, Nakagawa A, Kojima S, Takahashi H, Machida Y (2015) The complex of ASYMMETRIC LEAVES (AS) proteins plays a central role in antagonistic interactions of genes for leaf polarity specification in Arabidopsis. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol 4:655–671

Matsumura Y, Iwakawa H, Machida Y, Machida C (2009) Characterization of genes in the ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2/LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES (AS2/LOB) family in Arabidopsis thaliana, and functional and molecular comparisons between AS2 and other family members. Plant J 58:525–537

Matsumura Y, Ohbayashi I, Takahashi H, Kojima S, Ishibashi N, Keta S, Nakagawa A, Hayashi R, Saéz-Vásquez J, Echeverria M, Sugiyama M, Nakamura K, Machida C, Machida Y (2016) A genetic link between epigenetic repressor AS1-AS2 and a putative small subunit process some in leaf polarity establishment of Arabidopsis. Biol Open 5:942–954

Nakagawa A, Takahashi H, Kojima S, Sato N, Ohga K, Cha BY, Woo JT, Nagai K, Horiguchi G, Tsukaya H, Machida Y, Machida C (2012) Berberine enhances defects in the establishment of leaf polarity in asymmetric leaves1 and asymmetric leaves2 of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol 79:569–581

Nielsen CF, Hickson ID (2016) PICH promotes mitotic chromosome segregation: identification of a novel role in rDNA disjunction. Cell Cycle 15:2704–2711

Oh SA, Park KS, Twell D, Park SK (2010) The SIDECAR POLLEN gene encodes a microspore-specific LOB/AS2 domain protein required for the correct timing and orientation of asymmetric cell division. Plant J 64:839–850

Okushima Y, Fukaki H, Onoda M, Theologis A, Tasaka M (2007) ARF7 and ARF19 regulate lateral root formation via direct activation of LBD/ASL genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19:118–130

Ori N, Eshed Y, Chuck G, Bowman JL, Hake S (2000) Mechanisms that control knox gene expression in the Arabidopsis shoot. Development 127:5523–5532

Petricka JJ, Nelson TM (2007) Arabidopsis nucleolin affects plant development and patterning. Plant Physiol 144:173–186

Pinon V, Etchells JP, Rossignol P, Collier SA, Arroyo JM, Martienssen RA, Byrne ME (2008) Three PIGGYBACK genes that specifically influence leaf patterning encode ribosomal proteins. Development 135:1315–1324

Pontvianne F, Matía I, Douet J, Tourmente S, Medina FJ, Echeverria M, Sáez-Vásquez J (2007) Characterization of AtNUC-L1 reveals a central role of nucleolin in nucleolus organization and silencing of AtNUC-L2 gene in Arabidopsis. Mol Biol Cell 18:369–379

Pontvianne F, Abou-Ellail M, Douet J, Comella P, Matia I, Chandrasekhara C, Debures A, Blevins T, Cooke R, Medina FJ, Tourmente S, Pikaard CS, Sáez-Vásquez J (2010) Nucleolin is required for DNA methylation state and the expression of rRNA gene variants in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet 6:e1001225

Sakamoto T, Kamiya N, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Iwahori S, Matsuoka M (2001) KNOX homeodomain protein directly suppresses the expression of a gibberellin biosynthetic gene in the tobacco shoot apical meristem. Genes Dev 15:581–590

Semiarti E, Ueno Y, Tsukaya H, Iwakawa H, Machida C, Machida Y (2001) The ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana regulates formation of a symmetric lamina, establishment of venation and repression of meristem-related homeobox genes in leaves. Development 128:1771–1783

Serrano-Cartagena J, Robles P, Ponce MR, Micol JL (1999) Genetic analysis of leaf form mutants from the Arabidopsis Information Service collection. Mol Gen Genet 261:725–739

Shuai B, Reynaga-Peña CG, Springer PS (2002) The lateral organ boundaries gene defines a novel, plant-specific gene family. Plant Physiol 129:747–761

Takahashi H, Iwakawa H, Ishibashi N, Kojima S, Matsumura Y, Prananingrum P, Iwasaki M, Takahashi A, Ikezaki M, Luo L, Kobayashi T, Machida Y, Machida C (2013) Meta-analyses of microarrays of Arabidopsis asymmetric leaves1 (as1), as2 and their modifying mutants reveal a critical role for the ETT pathway in stabilization of adaxial-abaxial patterning and cell division during leaf development. Plant Cell Physiol 54:418–431

Tsukaya H, Uchimiya H (1997) Genetic analyses of the formation of the serrated margin of leaf blades in Arabidopsis: combination of a mutational analysis of leaf morphogenesis with the characterization of a specific marker gene expressed in hydathodes and stipules. Mol Gen Genet 256:231–238

Ueno Y, Ishikawa T, Watanabe K, Terakura S, Iwakawa H, Okada K, Machida C, Machida Y (2007) Histone deacetylases and ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2 are involved in the establishment of polarity in leaves of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19:445–457

Vial-Pradel S, Keta S, Nomoto M, Luo L, Takahashi H, Suzuki M, Yokoyama Y, Sasabe M, Kojima S, Tada Y, Machida Y, Machida C (2018) Arabidopsis zinc-finger-like protein ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2 (AS2) and two nucleolar proteins maintain gene body DNA methylation in the leaf polarity gene ETTIN (ARF3). Plant Cell Physiol 59:1385–1397

Yang JY, Iwasaki M, Machida C, Machida Y, Zhou X, Chua NH (2008) betaC1, the pathogenicity factor of TYLCCNV, interacts with AS1 to alter leaf development and suppress selective jasmonic acid responses. Genes Dev 22:2564–2577

Yao Y, Ling Q, Wang H, Huang H (2008) Ribosomal proteins promote leaf adaxial identity. Development 135:1325–1334

Ye J, Yang J, Sun Y, Zhao P, Gao S, Jung C, Qu J, Fang R, Chua NH (2015) Geminivirus activates ASYMMETRIC LEAVES 2 to accelerate cytoplasmic DCP2-mediated mRNA turnover and weakens RNA silencing in Arabidopsis. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005196

Zhang X, Yazaki J, Sundaresan A, Cokus S, Chan SW, Chen H, Henderson IR, Shinn P, Pellegrini M, Jacobsen SE, Ecker JR (2006) Genome-wide high-resolution mapping and functional analysis of DNA methylation in Arabidopsis. Cell 126:1189–1201

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Hidehiro Fukaki of Kobe University for the discussion of formation of auxin-induced lateral roots of Arabidopsis. We are deeply grateful to all members in our laboratories and collaborators for their helpful discussions. This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (Grant numbers JP20K06702, JP20K06696, JP19K22892, JP21K06218) and by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) KAKENHI (Grant numbers JP20H05402 and 16H06279 (PAGS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yasunori Machida is the recipient of the BSJ Research Award for 2013.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Machida, Y., Suzuki, T., Sasabe, M. et al. Arabidopsis ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2 (AS2): roles in plant morphogenesis, cell division, and pathogenesis. J Plant Res 135, 3–14 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10265-021-01349-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10265-021-01349-6