Abstract

Although the average tenure of CIOs has increased over the last years, the majority of CIOs have been in their positions for only three years or less. Nevertheless, some CIOs have been successful in their position for a long time. In this study, we use tenure as a proxy for success as a CIO. The goal of this paper is to examine factors that are critical to the success of long-term CIOs. For this purpose, we created and analyzed resumes of 384 CIOs. Out of these 384, we conducted 19 interviews with CIOs from top-tier companies and collected and analyzed both qualitative and quantitative data. In the process, we were able to identify nine factors that are critical for the success (CSF) of CIOs. These factors fall into three categories. Category “Personality” includes “Accepting and embracing change” (CSF #1), “Being perseverant to pursue long-term goals” (CSF #2), “Anticipating the future through visionary thinking” (CSF #3), and “Being empathetic to deal with uncertainty felt by co-workers” (CSF #4). The “Role Fulfilment” category includes “Cross-functional involvement and integration of the IT organization” (CSF #5), “Positioning and restructuring of the IT organization” (CSF #6), and “Well-connected and communicative leadership” (CSF #7). The “Organizational Environment” category consists of “Availability of skilled workforce” (CSF #8) and “Reporting line to the CEO” (CSF #9). CSFs 1, 2, and 3 were perceived as most important by the participating CIOs. The results may be of particular interest both to aspiring CIOs and equally their employing organizations, as they reflect what long-term CIOs value during their time in office.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The long-standing joke in the Information Technology (IT) industry that CIO stands for “Career Is Over” seems to be outdated (Harvard Business Review, 2010). Back then, a survey showed that nearly one in four Chief Information Officers (CIOs) were dismissed for poor performance (Nash 2009). Nowadays, however, there is evidence suggesting that CIOs are settling into their job and are experiencing longer tenures in their positions (CIO Magazine 2020). Nevertheless, according to a study by the consulting firm Korn Ferry, CIOs still have significantly shorter tenures at 4.6 years compared to Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) at 6.9 years (Korn Ferry 2020). Similarly, further studies conclude that although tenures are increasing on average, the majority of CIOs have been in their positions for only three years or less (CIO Magazine 2020; Kappelman et al. 2020).

The long tenures of CEOs are linked to superior organizational performance (Dikolli et al. 2014) and thus indicate the successful work of the executive. Correspondingly, CEOs are often replaced when corporate performance is low (Dikolli et al. 2014). In the same way, CIOs are dismissed for poor performance (Nash 2009).

A crucial factor is the role CIOs take on and the environment in which they operate (Drechsler 2020; Peppard 2010). The role of the CIO thereby depends on the environment and organization and can vary according to time and industry (Jones et al. 2020). A misalignment of the role can lead to lower than expected performance and even to the dismissal of the CIO (Karimi et al. 1996). This finding is also confirmed by a large-scale study by IBM Corporation (2011). In conversations with 3,018 CIOs, it was found that the most successful CIOs had reached an explicit agreement with their C-suite colleagues on the organization’s goals and how IT can best support and facilitate them (IBM Corporation 2011). Therefore, it seems prudent to argue that if CIOs operate in the appropriate role and perform it effectively, they can contribute to the success of the organization. This, in turn, allows them to stay in office for a long tenure.

In a recent paper, Jones et al. (2020) examined the background of CIOs. Their findings suggest that the background of a CIO has little to do with what the executives do once they are in office. Therefore, it interesting to learn what it means to be a CIO and what CIOs do once they are in the position (Jones et al. 2020).

Rapid technological progress is fundamentally changing industries and offers opportunities for companies but also comes with risks (Haffke et al. 2016). To complicate matters further, CIOs must engage in exploratory and strategic innovation while also exploiting incremental improvement opportunities to support the organization. Resolving this tension is called CIO ambidexterity (Kalgovas et al. 2014). In some companies, the multitude of these challenges has led to the implementation of a Chief Digital Officer (CDO) role. Reasons for the implementation of the CDO role are, for instance, an insufficiently shaped CIO role profile as well as a poor CIO reputation (Haffke et al. 2016). CIOs in organizations where the introduction of a CDO was not considered necessary and who have been in the position for an above-average time seem to have coped well with the previously mentioned fundamental changes and challenges. Therefore, it is interesting to determine what sets these CIOs apart and which factors contribute to successful work in the position.

In this vein, this paper tries to answer the following research question through an interview-based exploratory mixed-method study:

What factors are critical for the success of long-term CIOs?

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. First, literature pertinent to CIO success is reviewed in Sect. 2. The emphasis is on factors CIOs can influence themselves, i.e., competencies, personality traits, and the CIO role, as well as the environment in which a CIO operates. After that, in Sect. 3, the research methodology is described. Subsequently, the results of the interviews are presented, and an analysis of critical success factors is conducted in Sect. 4, and the results are discussed in Sect. 5. Section 6 concludes the paper and describes the limitations of this work as well as potential avenues for further research.

2 Literature review

2.1 CIO competencies

The many requirements make the CIO's job arguably one of the most demanding executive jobs in an organization, as well as a unique executive challenge (Gerth and Peppard 2014; Kappelman et al. 2020). CIOs need a wide range of competencies to meet these challenges.

Havelka and Merhout (2009) presented a framework consisting of four categories and 28 competencies IT professionals are required to have. The four categories are (a) personal traits, (b) professional skills, (c) business knowledge, and (d) technical knowledge (Havelka and Merhout 2009). The personal traits category represents characteristics that would make a person successful as an IT professional (Havelka and Merhout 2009). The professional skills category includes skills expected of professionals regardless of the field of work (Havelka and Merhout 2009). The knowledge specifically necessary for the domain of computer science is summarized under the category technical knowledge (Havelka and Merhout 2009). The business knowledge category includes concepts of how businesses operate, as well as specific knowledge of business concepts (Havelka and Merhout 2009). However, the framework is for IT professionals in general and not solely focused on top IT executives.

The role of the CIO is in constant change (Haffke et al. 2016). For this reason, Tahvanainen and Luoma (2018) used the framework for IT professionals by Havelka and Merhout (2009) and updated it for the CDO. In doing so, they compared which competencies were consistent with prior work and made new observations. Their result is a model also consisting of four categories, which are presented in Table 1.

For CDOs, there are also different types with different personality traits which differ from CIOs, and there are various reasons an organization may decide to create a separate CDO role (Tumbas et al. 2017). However, if CIOs drive rapid-paced digital innovation while simultaneously dealing with the IT infrastructure and can manage the corresponding conflicts that might arise, known as CIO ambidexterity, then there appears to be no need for a CDO (Tumbas et al. 2017). Furthermore, Weill and Woerner (2016) have shown that top-performing CIOs of successful organizations already perform the tasks of CDOs, such as paying close attention to external customers and maintaining an obsessive focus on innovation (Weill and Woerner 2016).

As the expectations, triggered by the evolution and adaptation of IT, have increased significantly toward the IT function and the CIO, Gouveia and Varajão (2019) have investigated required competencies for CIOs. Their preliminary results are summarized in their framework CIOCB—CIO Competences Baseline, which consists of technical, behavioral, and contextual dimensions (Gouveia and Varajão 2019). The technical dimension refers to competencies related to methods, processes, procedures, and techniques and corresponds to the technical competencies in the framework by Tahvanainen and Luoma (2018) (Gouveia and Varajão 2019). The behavioral dimension, which describes competencies related to attitudes and behavior, is covered by the personal and professional competencies in the framework by Tahvanainen and Luoma (2018) (Gouveia and Varajão 2019). The contextual dimension describes competencies related to the context of the organization and is partially covered in the framework by Tahvanainen and Luoma (2018) by the business competencies (Gouveia and Varajão 2019).

Furthermore, the skill to leverage personal networks inside and outside the organization can help CIOs enhance their role effectiveness (Smaltz et al. 2006; Zimmermann et al. 2016). CIOs furthermore indicated that external networking, in particular, is important (Peppard 2010).

We assessed the competencies of CIOs in our research using the framework by Tahvanainen and Luoma (2018). We decided against the CIO Competences Baseline (Gouveia and Varajão 2019) due to its preliminary character. Nevertheless, many aspects in the CIO Competences Baseline correspond to Tahvanainen and Luoma (2018), thus strengthening its validity and applicability. Although Tahvanainen and Luoma‘s (2018) framework is geared toward CDOs, we see applicability for CIOs. Effective and successful executive IT management should be embedded in the strategic management of the company, and IT is supposed to be part of the digital business strategy. Therefore, successful CIOs take on this challenge and should exhibit corresponding competencies.

2.2 CIO personality traits

In a recent review of CIO literature, Drechsler (2020) found that personality traits of IT executives and their impact are largely unaddressed by the existing body of research. One of the few studies addressing these qualities is the competence framework by Havelka and Merhout (2009), which captures personality traits that characterize a successful IT professional in the category of personality traits.

A CIO needs the flexibility to be able to accept changes and be sensitive about organizational culture (Havelka and Merhout 2009). The ability to be flexible is also relevant for CIOs when the organization has to deal with and manage uncertainty (Patten et al. 2009). According to Patten et al. (2009), flexible IT executives react proactively to unexpected changes and deal with uncertainties as if they were opportunities. A CIO's flexibility is also reflected in being sensitive to technological trends that will have an implication for budgeting or leading technical projects (Lee and Lee 2006).

Comparing traditional bricks-and-mortar organizations with e-businesses, Horner-Long and Schoenberg (2002) showed that future leaders will be less conservative and more risk-taking than leaders today. A greater need for risk-taking is also reflected in the fact that an innovative IT strategy often involves a certain degree of outcome uncertainty, which is why a CIO needs to be adventurous to execute the strategy (Li and Tan 2013). At the same time, the CIO must constantly be aware of the risk of cybercrime, data protection, and system failures that could temporarily shut down the company (Weill and Woerner 2013). A CIO, therefore, needs the ability to mitigate risks rather than avoid them to take full advantage of technology for the business (Babin and Grant 2019).

Two other personality traits are that a CIO should exhibit perseverance and visionary thinking (Tahvanainen and Luoma 2018). Perseverance is relevant because an IT executive has to deal with change resistance (Tahvanainen and Luoma 2018). Visionary thinking helps the CIO develop an IT or digitalization strategy (Tahvanainen and Luoma 2018). The CIO must also envision operational as well as strategic opportunities and be an advocate for new technologies (Peppard 2010).

In many industries today, continuous innovation is a prerequisite for a company's survival and success, and CIOs with their IT departments can help leverage a company's innovation potential (Whelan et al. 2015). IT departments can use creative solutions to solve the daily problems of their business partners (Babin and Grant 2019). Above all, creativity and creative thinking abilities are necessary for problem-solving (Havelka and Merhout 2009). Furthermore, executives responsible for digitization stated that their role requires creativity and a creative working environment to develop a new business while simultaneously supporting the existing products, services, and business (Tahvanainen and Luoma 2018).

Table 2 summarizes the personality traits used in this study and indicates, based on the literature, why a CIO should possess these traits.

2.3 CIO roles

A crucial factor is the role the CIO takes on and the environment in which the CIO operates (Drechsler 2020; Peppard 2010). Furthermore, it is important to avoid uncertainties about the expectations, behaviors, and consequences associated with the role to avoid role ambiguity (Peppard et al. 2011). Role ambiguity can ultimately lead to a CIO's dismissal and thus to a shortened tenure (Peppard et al. 2011).

According to Mintzberg (1971), the work of managers can be described in terms of various roles. These roles do not differ the functional or hierarchical level of the manager but in the relevance attributed to each role depending on job content, different skill levels, and expertise (Mintzberg, 1971). Thus Grover et al. (1993) have revealed that the managerial role importance of a CIO is not significantly different from that of a Chief Financial Officer (CFO) in the finance area, but is significantly different from those of the manufacturing and sales departments. Therefore, imitating the managerial style of successful functional managers from other disciplines is no guarantee for the success of a CIO (Grover et al. 1993).

That is only one reason several models about the CIO role exist in the literature, each with a different number of roles and different descriptions of the roles (Chun and Mooney 2009; Peppard et al. 2011; Preston et al. 2008a, b; Smaltz et al. 2006; Weill and Woerner 2013).

Smaltz et al. (2006) examined antecedents for CIO role effectiveness concerning the healthcare sector. In a factor analysis, six salient CIO roles could be found: (a) business strategist, (b) integrator, (c) relationship architect, (d) utility provider, (e) information steward, and (f) educator (Smaltz et al. 2006). Preston et al. (2008a, b), on the other hand, defined the role of the CIO in terms of the CIO’s strategic decision-making authority within the organization and the CIO’s strategic leadership capability. Accordingly, there are four leadership profiles for CIOs depending on decision-making authority and leadership capability (Preston et al. 2008a, b). The framework by Peppard et al. (2011) consists of five distinctive roles that follow different trajectories in different organizations, but in some, the role follows an evolutionary path. The appropriate role is determined by two factors: the criticality of information and technology for competitive differentiation and the maturity of its information leadership capabilities (Peppard et al. 2011).

The most current study regarding CIO roles is by Weill and Woerner (2013) and consists of four types (IT Services CIOs, External Customer CIOs, Embedded CIOs, and Enterprise Process CIOs). These types are the result of a survey of over 1,500 CIOs regarding how they spend their average time on CIO activities (Weill and Woerner 2013). The authors delineate key activities for each CIO type, the perceived most effective IT governance mechanisms, and the resulting enterprise performance measured by sales and/or returns. Weill and Woerner (2013) predict a development away from IT Services CIOs toward the other three types and provide guidelines for CIOs to make the transition.

Table 3 summarizes the literature on CIO roles and what criteria the authors used to classify the roles. Furthermore, the number of identified roles, the year of publication, and the sample size are indicated.

For several reasons, we decided to primarily rely on the work of Weill and Woerner (2013) for this paper: (a) it is the most recent publication, (b) it has the largest empirical base, and (c) it follows a multi-year, multi-method approach.

2.4 Management environment

There are factors that a CIO cannot influence or only influence indirectly at best. For example, the integration with top management is not under the CIO’s direct control (Preston et al. 2008a, b). Also, CIOs on their own can contribute little to the company's success without the engagement of the leadership team (Gerth and Peppard 2016).

The savviness and experience of business executives regarding IT reflect the engagement and involvement in IT issues as well as the relevance of attitude toward IT (Earl and Feeny 2000; Gerth and Peppard 2014). Through knowledge in IT, business executives can better understand and appreciate how IT can help in achieving business objectives (Gerth and Peppard 2014). If the digital literacy of executives is at low levels, this could restrict the organization’s potential for exploiting IT (Peppard et al. 2011). Furthermore, IT-competent business managers with high levels of IT knowledge and experience can build strong relationships with IT staff and establish a shared understanding among them (Bassellier et al. 2003). Furthermore, the CIO should seek a common understanding with the CEO, especially regarding the potential role of IT in the organization and how the CEO wants to establish the role of IT in the organization (Johnson and Lederer 2010).

Many companies still do not see IT as a strategic driver of value in their business but as a cost factor, and as a result, the role of the CIO might not be especially relevant (Peppard 2010). Nevertheless, it is also a fact that most organizations today would not survive without their IT systems, which reflects the crucial role of IT (Peppard 2010). Furthermore, the extent to which a company depends on IT varies depending on the organization and industry (Krotov 2015).

Thus, higher demands are placed on a CIO when the business strategy is strongly shaped by IT (Peppard 2010). Consequently, the alignment of IT should be understood as a two-sided issue (Earl and Feeny 2000). IT should be a partner to the business, enabling and driving changes to business strategy (Luftman 2003). In addition, the strategic alignment of IT generally leads to a higher contribution of IT to the organization, for example, by deploying relevant IT (Johnson and Lederer 2010). The degree to which a CIO is involved in business decision-making can be a good indicator of how integrated IT is in the business (Peppard 2010).

A CIO should also make strategic decisions as a business leader for the organization and decide through which IT initiatives the business needs can best be pursued (Preston et al. 2008a, b). The degree to which a CIO is free to do so is reflected in the decision-making authority (Preston et al. 2008a, b). Therefore, a CIO with a high degree of decision latitude is not permanently controlled by the CEO (Arnitz et al. 2017). This is beneficial for CIOs because their decision-making authority has a direct impact on the influence of IT within the organization and the value provided by IT (Preston et al. 2008a, b).

Table 4 summarizes the factors related to the management environment used in this study. Also, the table explains what each factor reflects.

3 Research methodology

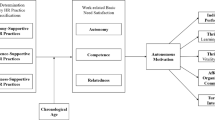

To answer the research question and identify Critical Success Factors (CSFs), we followed a mixed-method approach with a focus on qualitative research methods. This research approach can be carried out in a variety of combinations concerning the implementation sequence (Remus and Wiener 2010). We started with a literature review (Sect. 2) to provide a foundation for this study. For the expert interviews, we used a questionnaire with open- and closed-ended questions. The qualitative data were analyzed using a coding procedure and the quantitative data using statistical analysis. Figure 1 illustrates our approach taken.

3.1 Operationalization of “success of a CIO”

Due to the ill-defined success of IT and because benefits are often difficult to attribute to newly introduced systems, it is hard to measure the success of CIOs (Gerth and Peppard 2016; Krotov 2015). A CIO might therefore interpret success differently than his C-level colleagues (Gerth and Peppard 2014). Moreover, in the absence of objective metrics for evaluating IT, executives often have no choice but to evaluate the CIO based on their perceptions (Gonzalez et al. 2019).

Transitioning to a new leadership position takes time. It can take up to six months until CIOs have created a sufficient understanding of the organization and can start making their first significant and impactful decisions (Gerth and Peppard 2014). A successful transition from an IT leader to a recognized business leader may even take 24 to 36 months (Gerth and Peppard 2014).

The long tenure of CEOs is associated with superior organizational performance (Dikolli et al. 2014) and thus indicates the successful work of the executives. However, CEOs are often replaced when corporate performance is low (Dikolli et al. 2014). The majority of CIOs have been in their positions for only three years or less (CIO Magazine 2020; Kappelman et al. 2020).

Given the short time in the position, it can therefore be questioned whether CIOs were dismissed due to poor performance. Because of the ill-defined success of IT and because a successful transition into the CIO position takes time, we use CIO tenure as a proxy for success and argue that successful CIOs stay in their position for an above-average tenure.

Since only CIOs from Germany were interviewed for the study, the special circumstances of German labor law need to be considered. Employees in Germany are protected from job termination by labor law and cannot simply be dismissed because of poor job performance. However, the legal protection from job termination only applies to “regular” employees, i.e., they do not apply to managers or executives (“leitende Angestellte”). All participants in our study were senior IT executives and thus did not benefit from special protection regarding job termination, i.e., they could be dismissed for poor job performance and, therefore, their tenure length is not biased by labor law-induced aspects.

3.2 Critical success factor methodology

CSFs are “the limited number of areas in which results if they are satisfactory, will ensure successful competitive performance for the organization. They are the few key areas where things must go right for the business to flourish” (Rockart 1979, p. 85). CSFs are areas of activities that should therefore receive constant and careful attention from management (Rockart 1979). In this paper, we, therefore, focus on CSFs that impact the execution of a CIO's role and that can contribute to successful work, ultimately leading to a long-term tenure as an IT executive. According to Remus and Wiener (2010), CSF research can be divided into different research phases, and different research methods can be used for this purpose. The four phases, following Esteves (2004), are (a) State-of-the-art, (b) CSF Identification, (c) CSF Analysis, and (d) CSF Management.

The state-of-the-art phase looks at existing research in the field. In the paper at hand, this is represented by our literature review in Sect. 2. The purpose of the identification phase is to identify and define CSFs (Esteves 2004). Qualitative methods such as literature review, expert interviews, or grounded theory are suitable for this phase (Remus and Wiener 2010). In the present study, this is part of our demographic and, primarily, our CSF study based on expert interviews and a CSF ranking.

The purpose of the analysis phase is to analyze CSF relevance in general by using quantitative methods such as web surveys or statistical analysis (Remus and Wiener 2010). For this research, we asked the participants to rank the identified CSFs, and we reflect upon the results. The final phase, the management phase, aims to identify and structure management activities around CSFs to make the findings actionable (Remus and Wiener 2010). We cover this aspect in our paper in the last results Sect. 4.4.

According to Remus and Wiener (2010), especially in CSF research, a multi-method design offers advantages, where the research comprises several different phases, with each phase using different suitable methods. We follow this recommendation and combine a demographic study with CIO interviews and a quantitative ranking of the identified CSFs.

Critical success factors are widely researched and applied with different perspectives, especially regarding projects and project management (Esteves 2004; Remus and Wiener 2010). However, in the area of top executive positions, few CSF studies have been undertaken (Ferguson and Dickinson 1982; Kanji & e Sa´ 2001; Martin 1982; Raghunathan et al. 1989; Shi & Bennett 1998). Rockart (1982), for example, identified a CSF set for IS executives consisting of service, communication, IS human resources, and repositioning the IS function. More recent studies examine the success of top executives, especially the CIO, but without specifically using CSF (Higgs 2006; Li and Tan 2013; Peppard 2010; Smaltz et al. 2006). Rockart considers these CSFs as key techniques and processes an executive can use to manage critical areas (Rockart 1982). Shi and Bennett (1998), on the other hand, examined CSFs that are relevant for the successful career path of IS executives.

Although the CSF methodology is primarily applied in project terms, studies have also been conducted in the area of top management positions (Ferguson and Dickinson 1982; Kanji & e Sa´ 2001; Martin 1982; Raghunathan et al. 1989; Shi and Bennett 1998). However, the existing literature is scarce and, in many cases, rather dated (Ferguson and Dickinson 1982; Kanji & e Sa´ 2001; Martin 1982; Raghunathan et al. 1989; Shi and Bennett 1998). Nevertheless, previous studies show that CSF methodology can also be applied to research issues associated with top management positions. Additionally, more recent studies in this field seem to be valuable.

3.3 Data collection

3.3.1 CIO identification & selection

The unit of analysis of our study is CIOs in large companies, and we focus our research on Germany. The basis for the identification of CIOs is the “Top-500″ company database of the German branch of the CIO Magazine (CIO Magazin 2020). The database lists companies based in Germany with a turnover of more than one billion Euro and was chosen for several reasons: (a) It contains information on companies such as turnover, number of employees, and type of industry, (b) key figures on the company's IT organization, and (c) the current IT executive. For the study, all companies with more than 5,000 employees were included because smaller companies often do not have an IT organization of significant size and/or do not have a CIO. After applying this criterion, 330 companies remained for further investigation. The database was queried in mid-October 2020. Updates or changes after that date are not included in this paper.

The social network LinkedIn was primarily used to gather information about CIOs. If a CIO did not have a profile on LinkedIn, the German social network alternative Xing or press releases were used. The following information was collected from these sources: (a) the beginning and end of tenure, (b) the previous position, (c) the degree and specialization of education, and (d) the current title of CIO. The current IT executive of a company and the predecessor were included in the analysis. Data from LinkedIn and Xing were collected until the end of October 2020. The length of the tenures thus includes the month of October 2020. All transitions of CIOs to new positions from this date forward are not included in our data set.

In total, data were collected on 384 CIOs from the previously mentioned 330 companies. However, information on CIOs could only be identified for 268 companies. Thus, no data on CIOs is available for 62 companies. These 62 companies are therefore not included in the data set. The tenures of all CIOs cover a period from 1990 to 2020, but only nine CIOs became CIO before 2000. Sixty CIOs took office between 2000 and 2010 and 315 from 2010 onwards.

Figure 2 provides an overview of the data collected on the 384 CIOs. In line with the terminology used in our paper, the most common role title for IT executives is “Chief Information Officer.” At 66%, most CIOs (252) have at least a master's or equivalent degree. Nineteen percent of CIOs also have a doctorate. The most common field of education is economic sciences (comprising business administration/management and economics), with 46% of CIOs. However, 97 CIOs (25%) have a background in natural science, and 58 CIOs (15%) have a background in engineering sciences. One hundred fourteen IT executives (30%) were already CIOs in their previous position; 138 IT executives (36%) were previously employed within IT, and 124 IT executives (32%) originated from business units or outside the IT organization. Furthermore, the data shows that at 63%, more than half of CIOs (241) are hired from another company (“external”).

For some CIOs, no information regarding their backgrounds could be found from the above sources. The missing information will be declared as “Not specified” in the further course of this paper.

Table 5 displays the descriptive statistics of the tenures by showing arithmetic mean (M), standard deviation (SD), and median (Mdn). The median tenure of all 384 is 4.0 years, while it is 4.7 years for completed tenure and 3.7 years for tenure in progress.

Many executives were in office and had below-median tenure in October 2020. However, these CIOs may also have an above-median tenure in a few years and might thus be considered successful. Therefore, the median value of completed tenures is used to form two groups of CIOs: (a) all CIOs who have a tenure above or equal to 4.7 years and (b) all CIOs with tenure less than the median of 4.7 years.

As Table 6 shows, 164 of all CIOs have a tenure greater than or equal to 4.7 years. These CIOs are the target group for the rest of this study.

Once selected, the 164 CIOs with above-median tenure were contacted. We primarily used LinkedIn for this purpose, as the social network was already being used for data collection, and email addresses were not available for every CIO. If executives did not have a profile on LinkedIn, we contacted them via email. In total, 19 CIOs responded to our request and agreed to be interviewed. This corresponds to a response rate of 11.6% percent.

Table 7 summarizes the demographics of the interviewee panel and details of the organizations the CIOs worked for in their longest tenure. If the longest tenure is the current one, the length is calculated to include October 2020. Since the database was queried in October 2020, the turnover and number of employees of the companies refer to the year 2019. Reporting line indicates the executive to which the CIO reports.

As mentioned above, for 62 of the 330 companies, we were unable to identify a CIO. To examine potential effects from sample biases, we assessed whether the 62 companies differed from the overall population by performing a Mann–Whitney U test. The test shows that there is a significant difference in the turnover between companies where no CIO could be identified (Mdn = 2957 m €) and companies where we could identify a CIO (Mdn = 4164 m €), U = 6654.5, p = 0.015. However, a Mann–Whitney U test also shows that there is no significant difference in the number of employees between companies where no CIO could be identified (Mdn = 13,100) and companies where we could identify a CIO (Mdn = 16,350), U = 7260.5, p = 0.122. Furthermore, we used the available key figures on the company's IT organization for analysis. There is a significant difference in the IT budget between companies where no CIO could be identified (Mdn = 47.5 m €) and companies where a CIO is included in the data set (Mdn = 71.5 m €), U = 6349.0, p = 0.004. However, there is no significant difference regarding the number of IT employees between companies where no CIO could be identified (Mdn = 245) and companies where we could identify a CIO (Mdn = 330), U = 7123.0, p = 0.080. In summary, the 62 companies without CIOs include a disproportionate number of companies of smaller size. It is possible we were unable to identify a CIO, because smaller companies have less of a public presence; thus, less information is publicly available. Additionally, there is the possibility that smaller companies do not have a CIO at all.

As Table 6 shows, 164 of all CIOs are the target group for our study. With respect to a potential sample bias, we assessed whether the 19 interviewees differed from the target group of 164; we again performed a Mann–Whitney U test. There is no significant difference in the turnover between companies of the interviewees (Mdn = 3959 m €) and companies of the target group (Mdn = 5050 m €), U = 1357.5, p = 0.918. There is also no significant difference in the number of employees between companies of the interviewees (Mdn = 14,400) and companies of the target group (Mdn = 17,873), U = 1361.0, p = 0.932. Also, in relation to the IT budget, there is no significant difference between companies of the interviewees (Mdn = 98.0 m €) and companies of the target group (Mdn = 87.0 m €), U = 1279.0, p = 0.613. Furthermore, there is no significant difference in the number of IT employees between companies of the interviewees (Mdn = 464) and companies of the target group (Mdn = 378), U = 1279.0, p = 0.640. In addition, the selected interviewees (Mdn = 10.3 years) have longer median tenures than the CIOs from the target group (Mdn = 8.1 years). However, the difference is not statistically significant, U = 1005.5, p = 0.056. In summary, we see that the company background of the 19 interviewees does not differ significantly from the company backgrounds of the CIOs from the target group of 164. However, it should be noted that no CIO is represented from the financial, construction, or healthcare industry type in our queried sample of 19.

In addition, we looked at the characteristics of the CIOs themselves. A chi-squared test shows no statistically significant difference in the subject of education between interviewees and the remaining CIOs from the target group (χ2(3, N = 141) = 4.196, p = 0.241). There is also no difference in the field of education (χ2(3, N = 148) = 3.187, p = 0.364). Also, in relation to the previous position there is no statistically significant difference (χ2(3, N = 159) = 5.286, p = 0.071). Therefore, we are confident that our sample of 19 interviewees and their characteristics does not significantly differ from the 164 CIOs from the target group.

3.3.2 CIO interviews

The interviews took place from January to February 2021. Due to the pandemic, all interviews were held via video conference. All questions were presented to the CIOs visually through a guiding presentation. The interviews were conducted in German by two interviewers and were initially scheduled for 30 min since all respondents had tight schedules and could not make much time available for the interview. The actual length of the interviews, however, ranged from 30 to 60 min, about 40 min on average. For all closed questions, respondents also had the opportunity to give reasons for their answers. We took detailed notes on the responses during the interviews and coded the responses afterwards. To encourage the CIOs to speak freely, it was decided not to record the interviews. Before the interviews, participants were assured that the content of the interview and the transcripts would be kept confidential (Myers and Newman 2007). Since the interviews were conducted in German, the responses and quotes were translated for this paper.

The interviews were conducted using a structured questionnaire, which can be found in the appendix. This form was chosen because the brief duration of only 30 min was set for the interviews to facilitate a high number of participants. CIO competencies and personality traits, CIO roles, and the management environment form the core of each interview. Two open-ended questions were asked to start the interview and “break the ice:” First, what makes the CIO position appealing compared to other management positions? Second, what successes have the CIOs been able to achieve for their company? The question aims to determine which activities a CIO has successfully carried out to date and which of these he or she considers most important. This enriches the understanding of the individual CIO’s success beyond an above-median tenure.

Since the selected CIOs all work in large companies and have been in their job for a long time, it can be assumed that they have distinctive skills in each category of the competency framework used. Therefore, we decided to let the interviewees rank the categories.

To focus on the personality traits, we decided to ask questions or the personality competencies category separately. To do this, we used the five personality traits from the section “CIO Personality Traits.” CIOs were again asked to rank these personality traits in order of relevance to their job as CIOs. Also, the CIOs were asked what other personality traits a CIO should have beyond the five predefined ones.

For the reasons stated in the “CIO Roles” section, we used Weill and Woerner’s (2013) types of CIOs to assess the CIO roles. Since the names of these roles are not self-explanatory as we found out in a test-run of the survey, we relabeled them slightly by drawing on the labels from a literature analysis on CIO roles by Hütter and Riedl (2017). Therefore, the names used for the roles in this study are (a) technology provider, (b) innovation driver, (c) relationship manager, and (d) integration advisor (Hütter and Riedl 2017). The names and definitions used in the interview can be obtained from the appendix. In the interview, CIOs were asked how much time, on average, they spent in these roles. How they allocate their time is an indicator of what CIOs consider important or at least what is expected of them (Jones et al. 2020). Additionally, to get a forward-oriented perspective, we wanted to know from CIOs if this allocation will change in the future.

To examine the environment in which a CIO operates, we used the factors from the “Management Environment” section. These four factors were measured using Likert-type questions on a 1-to-5 scale (1 = Very low, 2 = Low, 3 = Moderate, 4 = High, 5 = Very high).

In the end, the CIOs were asked two more open questions. First, we wanted to know what challenges and opportunities the CIO will face in the future. Second, we asked the CIOs what conditions they would like to create to continue to succeed in the future or even increase their success.

3.4 Applied methods

SPPS Statistics 27 was used to analyze the quantitative data. This involves questions about (a) competencies, (b) personality traits, (c) roles, and (d) management environment as well as CSF analysis.

Borda's methods were used to evaluate the ranking questions because the collection of Borda-inspired methods is intuitive and easy to understand (Lin 2010). In rank aggregation (RA) methods, Borda-inspired methods are classified under non-optimization-based methods (Li et al. 2019). RA is applied to either aggregate “a few long-ranked lists” or aggregate “many short-ranked lists” (X. Li et al. 2019). In this study, the latter is applied. In the method originally proposed by Borda, aggregate ranks were computed based on the (a) arithmetic mean (ARM) for full-ranked lists, but commonly proposed aggregation functions also include (b) median (MED), (c) geometric mean (GEM), and (d) a special case of the p-norm (L2N) (Lin 2010). There are two ways to arrange rank data: item-based format or rank-based format (X. Li et al. 2019). For this study, the first one was used. Each row represents a competency, each column represents a participant, and the corresponding cell indicates a particular participant's competency rank.

Likert-type questions were used for the factors regarding the management environment. These questions are measured using an ordinal scale. Boone and Boone (2012), therefore recommend using the (a) median, (b) mode, and (c) frequencies for the descriptive statistics. Furthermore, it will be analyzed whether CSF differ between the industry type of the respondents' companies. For Likert-type questions regarding the management environment, Sullivan and Artino (2013) suggest using the Mann–Whitney U test. The Mann–Whitney U test is a nonparametric statistical test that evaluates differences between two independent groups using a non-normally distributed, at least ordinally scaled variable (Mann and Whitney 1947). Therefore, we applied this test to the factors related to the management environment and the time allocation of CIO roles.

For coding, the software QDA Miner Lite was used. As suggested by Remus and Wiener (2010), an open coding procedure was chosen for the analysis of the interview data. Open coding aims to identify different concepts and themes for categorization (Williams and Moser 2019). Since we are conducting an exploratory study, we have taken an inductive approach to coding to develop the codes “directly” from the data (Skjott Linneberg and Korsgaard 2019). According to common practice, we considered a code to be a word, phrase, or sentence fragment of different emergent themes (Williams and Moser 2019). Before coding, the interview protocols were read several times to get an overview of the answers. In doing so, we searched for thematic connectivity leading to thematic patterns (Williams and Moser 2019). Following Skjott Linneberg and Korsgaard (2019), we employed the act of coding not as a linear process but rather as a recurring cycle with feedback loops. Thereby, we considered the initial round to be more descriptive to create an overview of the data and the second round to be more analytical to focus on creating patterns in the data (Skjott Linneberg and Korsgaard 2019). In the first round, all 19 interview protocols were coded. After the first round, the codes were examined and checked for inconsistencies and/or errors. After that, the second round of coding was carried out to refine the codes from the first cycle. The result of open coding is a list that characterizes codes and categories attached to the interview protocols (Flick 2009).

Having identified the CSFs after manual coding, we reached out to the participating CIOs again in June and July 2021 and asked them to rank the identified CSFs in order of perceived importance. The ranking was analyzed using Borda’s methods as outlined above. All 19 CIOs took part in the follow-up ranking survey. We used Kendall's coefficient of concordance (W) to test the ranking survey for evidence of consistency between the respondents who assigned the ranking.

4 Results

This section first provides the descriptive results of our interviews (Sect. 4.1) and subsequently focuses on CSF identification (4.2), CSF analysis (4.3), and CSF management (4.4).

4.1 Descriptive results

4.1.1 Appeal of the position

When asked with an open question what CIOs find appealing about their position, two reasons were mentioned particularly frequently. As Fig. 3 shows, these are (a) the variety of topics a CIO can work on and (b) the cross-sectional function a CIO assumes. The percentage indicates how many of the total CIOs named a specific topic that can be assigned to the respective code. The absolute frequency is also given in brackets. This number may differ for the same percentage, as multiple responses were possible. Two other aspects were also mentioned particularly frequently: on the one hand, the split of the role into operational tasks and strategic tasks, and on the other hand, the fast pace of IT. Both aspects were mentioned by 47% of CIOs.

4.1.2 Greatest achievements

As Fig. 4 shows, two-thirds of CIOs see their greatest achievements in having positioned and restructured their IT organization. The second most frequently mentioned success, by almost half of the CIOs, was having initiated or completed a cultural change in their (IT) organizations. Furthermore, 42% of respondents see the delivery of successful projects and the consolidation of the IT landscape as one of their greatest achievements.

4.1.3 CIO competencies

In terms of competencies, a clear picture emerges. As shown in Table 8, for each aggregation function, the order of competencies is the same. Leadership was rated as the most important competency, followed by business, and technical is the least important of the three competencies.

Figure 5 shows that 13 CIOs ranked leadership competence first, whereas not a single CIO ranked this competence third and thus last. Therefore, CIOs see leadership as the most important competency. Business competence was ranked second by the majority of CIOs. Two CIOs ranked this competency first, and two CIOs ranked it last. Technical competence was ranked last by the majority of CIOs. Only one CIO ranked this competency as most important, and two ranked it second. Only one CIO chose technical as the most important competence while choosing business as the least important competence. The results show that technical competency plays a subordinate role for the interviewees.

Three of the CIOs (12, 15, and 19) noted that it is not appropriate to put these competencies in a certain order because all competencies are equally important.

4.1.4 CIO personality traits

Compared to competencies, CIOs ranked personality traits less consistently in comparison to the competencies. Thus, the ranks of the aggregate functions from Table 9 are also not consistent. There is a clear ranking for perseverance, visionary thinking, and flexibility using Borda’s aggregates. In contrast, there is no consistent ranking for risk-taking and creativity. Since ARM and L2N match, the ranking of these two functions is used. Applying this logic, the most important personality traits, in descending order, are perseverance, visionary thinking, flexibility, risk-taking, and creativity.

Figure 6 shows the individual personality trait rankings. For flexibility, it stands out that the CIOs consider this personality trait neither particularly important nor unimportant. Creativity, on the other hand, was not considered the most important characteristic by a single CIO. Only one CIO did not rank the personality traits, stating that all traits are equally important, and a ranking is not appropriate.

The interviewees mentioned additional personality traits, some of which can be subsumed under the pre-defined personality traits. However, the following cannot be subsumed under the pre-defined ones: (a) empathy, (b) willingness to change, (c) persuasiveness, and (d) openness. Empathy was mentioned by five (3, 4, 7, 8, 15) of the 19 CIOs. That accounts for 26% of the total CIOs.

4.1.5 CIO roles

CIOs were asked to indicate the average amount of time they have spent in roles and the amount of time they plan to spend in the future. As shown in Fig. 7, the average time spent by all CIOs to date has been evenly distributed across the four roles. The median for time spent to date is 25% for each of the technology provider, innovation driver, and integration advisor roles. In the role of the technology provider, the varying time allocation is also notable. Thus, CIOs have spent between 10 and 50% of their time in this role to date. In the case of time spent in the future, greater differences can be seen between the roles. Only the time spent in the role of innovation driver is increasing, while the time spent as a technology provider is decreasing.

Table 10 presents the time allocation change in the respective roles and indicates the mean value of the previous and future time allocation. Out of 19 interview participants, 13 do not plan to allocate time differently in the future. Table 10, therefore, distinguishes between all CIOs and the six CIOs who plan to allocate their time differently in the future.

However, six CIOs also expect the time allocation to change. Therefore, Fig. 8, only looks at these six CIOs. This illustration makes the decrease in the technology provider role and the increase in the innovation driver role more apparent. A decrease can also be seen in the role of integration advisor, while the time spent in the relationship manager role is increasing. Figures 7 and 8 also illustrate the importance of the relationship manager role. The time allocation in this role will remain stable in the future, regardless of the industry type.

We also examined whether the distribution differs by industry type. Due to the number of companies, a distinction was only made between manufacturing companies and service providers. The service providers include companies from the following industry types: (a) banking, (b) transportation, (c) retail, (d) energy, and (e) media. Manufacturing companies’ industry types include: (a) automotive, (b) chemical, (c) food, and (d) manufacturing. Regarding time allocation to date, a Mann–Whitney U test shows that there is a significant difference in the technology provider role between CIOs working in manufacturing companies (Mdn = 15%) and CIOs working in service provider companies (Mdn = 30%), U = 19.0, p = 0.041. Also, in the future time allocation, a Mann–Whitney U test shows that there is a significant difference in the technology provider role between CIOs working in manufacturing companies (Mdn = 10%) and CIOs working in service provider companies (Mdn = 30%), U = 12.5, p = 0.007. Concerning the future innovation driver role, there is also a significant difference between CIOs working in manufacturing companies (Mdn = 35%) and CIOs working in service provider companies (Mdn = 25%), U = 13.5, p = 0.009. Table 11 shows the overall statistics of the Mann–Whitney U test. No differences occurred for the remaining roles using exact significance.

As Fig. 9 shows, CIOs in manufacturing companies have spent less time in the technology provider role than CIOs in service provider companies. In contrast, CIOs from manufacturing provider companies spent more time in the innovation driver role than CIOs in service companies. However, this difference is not statistically significant. Only the time allocation in the integration advisor role is comparable for both industry types.

In the future, CIOs in manufacturing companies will continue to spend significantly less time in the role of technology provider than CIOs in service provider companies. However, as Fig. 10 indicates, CIOs in manufacturing companies plan to spend significantly more time in the role of the innovation driver than CIOs in service provider companies.

4.1.6 Management environment

Table 12 presents the descriptive statistics of Likert-type responses regarding the management environment. CIOs rated four factors on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Very low, 2 = Low, 3 = Moderate, 4 = High, 5 = Very high). When it comes to the IT competence of the business units, the most common rating is moderate. The most common rating for the relevance of IT is high. No CIO rates the relevance as low or very low. The median for involvement in business strategy development is moderate, with the most common rating being low. In contrast, most CIOs rated decision-making latitude in the development of IT strategy as very high, with a median of high.

Figure 11 illustrates the distribution of the individual responses for the four factors. In the assessment of IT competence, there is a noticeable tendency toward a central rating. One reason for this is that many CIOs chose to rank moderate as the average value because competence varies from one department to the next. At just under 90%, almost all CIOs rated the relevance of IT at least high or very high. When it comes to IT being involved in the business strategy development, the distribution is even. Only the rating very low was not selected. In terms of IT strategy development, data shows that CIOs feel a high degree of decision latitude. Almost 75% rated this factor as high or very high. However, some CIOs also emphasized that they do not use decision-making freedom for their benefit alone.

We also examined the management environment for whether the distribution differs by industry type. In contrast to the roles, there are no differences between CIOs in manufacturing companies and CIOs in service provider companies. Table 13 summarizes the overall statistics of the Mann–Whitney U tests.

4.1.7 Future challenges and opportunities

When asked openly regarding their future biggest challenges and opportunities, CIOs mentioned finding qualified staff (“Employees”) most often. As Fig. 12 shows, keeping up to expectations and achieving a cultural change were named second most often. Just under a third of CIOs continue to see the perception of IT and the CIO as a challenge. However, the respondents also answered that this challenge can be an opportunity at the same time. The only specifically IT-related aspect in the most frequently mentioned answers is security.

4.1.8 Preconditions for the future

As Fig. 13 indicates, for more than half of the CIOs, the positioning of the CIO, i.e., the reporting line, is an important prerequisite for successful work in the future. Only six of the CIOs still report to the CFO, while the majority report to the CEO.

Forty-two percent of CIOs also discussed the future IT organization. For many respondents, an effective and efficient IT architecture and IT infrastructure are other prerequisites for the future.

4.2 CSF identification

4.2.1 Overview

Based on the interviews, we were able to identify nine critical success factors. As the CSFs relate to different levels or contexts, we further categorized the CSFs. The category “Personality” comprises CSF 1, 2, 3, 4, all referring to the personality of the CIO. CSFs 5, 6, 7 are grouped under the category “Role Fulfilment.” Category “Organizational Environment” consists of CSFs 8 and 9. Table 14 summarizes the identified CSFs.

The following three sub-sections describe each CSF in each CSF category

4.2.2 Personality (CSFs #1 to #4)

4.2.2.1 CSF #1—Accepting and embracing change

Having initiated or completed a change of organizational culture is considered by CIOs to be one of their greatest achievements. For a successful culture change, executives must set a good example and be role models for the organization. According to the respondents, openness and willingness to change are relevant personality traits. CIOs need these traits to embrace cultural change themselves. Successful CIOs consider the variety of topics and the fast pace of IT as appealing. For example, regarding the variety of topics, CIO 15 said, “the variety of activities is excellent and will also provide an exciting work environment in the future.” CIO 16 had the same opinion, stating, “you can also pick and choose the topics. Sometimes doing something operational and sometimes more of a strategic topic.” Concerning the fast pace of IT, CIO 10 said, “in my total 35 years as a CIO, nothing has been repetitive. There is constant change.” It seems that long-serving CIOs are embracing the constant change of tasks. CSF #1 is, therefore, accepting and embracing change.

4.2.2.2 CSF #2—Being perseverant to pursue long-term goals

According to the interviewed CIOs, perseverance is especially necessary for large companies as well as large projects. CIO 1, who ranked visionary thinking first and perseverance second, compared the CIO to a city architectural planner.

“A city only changes by a few percent every year. It is the same with IT. You have a lot of legacy systems, and you can only change them a little bit at a time. You need a clear plan for that. And you cannot just cut big swaths of change. That's why you need perseverance.”

CIO 3 saw a connection between perseverance and tenure, stating, “for a long tenure, perseverance is important.” For CIO 18, perseverance is a relevant personality trait “to reach the goal and get there.” The results show that perseverance was rated as the most important personality trait. CSF #2 is, therefore, being perseverant to pursue long-term goals.

4.2.2.3 CSF #3—Anticipating the future through visionary thinking

After perseverance, visionary thinking was ranked as the second most important personality trait. According, e.g., to CIOs 3 and 10, visionary thinking was necessary to think and plan for years. CIO 10 added, “you have to stay ahead of the company but also ahead of your employees.” CIO 18, who ranked visionary thinking as the most relevant personality trait, justifies this by saying, “if I don't have a clear vision, everything else is messing around.” For CIO 5, visionary thinking meant “having the right strategic discussions with foresight and pre-emptively, not just when you need something as a CIO.” CIO 2 saw the importance of visionary thinking, as it is necessary “to think years ahead because IT systems have a long half-life and are sometimes in use for decades.” One further success factor, CSF #3, is anticipating the future through visionary thinking.

4.2.2.4 CSF #4—Having empathy to deal with uncertainty felt by co-workers

Many CIOs mentioned empathy as an additional relevant personality trait. For example, CIO 4 said, “I have to communicate differently with each department and empathize and respond to their different thought patterns.” CIO 7 mentioned that “as a CIO, you have to walk in your colleagues' brains. That's how you learn what the business needs to succeed.” As CIO 8 said, “IT is the most important tool for change processes; change hardly works without IT.” However, change is always associated with uncertainty on the part of those affected. For CIO 3, empathy was important to “be able to put yourself in others' shoes and feel your way in.” Putting themselves in people's positions, therefore, seems to be important for the CIOs. Therefore, having empathy to deal with uncertainty felt by co-workers is CSF #4.

4.2.3 Role fulfilment (CSFs #5 to #7)

4.2.3.1 CSF #5—Cross-functional involvement and integration of the IT organization

As our descriptive results showed, from the respondents' point of view, the cross-sectional function IT performs is particularly appealing to the CIO's job. Commenting on the cross-functional role, CIO 19 said, “you get an insight into all the processes of the company, and because you are out and about in many units, as a CIO you can also leverage optimization potential between these units.” CIO 3 went even further, stating, “you influence ways of working from all functions and, in turn, the success of the company.” To be successful as a CIO, according to CIO 6, “you have to be involved in all business processes and have interaction with all functions.” For CIO 19, being involved meant “not only having contact with people but also being involved with all the processes of the business units.” The answers show how important IT executives consider it to be involved and present in all areas of the company. For this reason, cross-functional involvement and integration of the IT organization is CSF #5.

4.2.3.2 CSF #6—Positioning and restructuring of the IT organization

CIO 11 saw his greatest achievement as having “transformed IT from a German IT into a global IT that not only supports [my company] in Germany but supports it globally.” CIO 9 perceived his greatest achievement in “the repositioning of IT,” and as a result, “IT is no longer seen as a cost factor. There is also no longer an IT cost cap, but if the business unit needs solutions, then we look at how these costs can be covered.” CIO 5 described the repositioning of the IT organization as follows, “IT was disconnected at the beginning of my tenure and is now an integral part of the strategic discussion and the value chain again.” CIO 6 claimed one of the biggest achievements was “to bring IT back together organizationally and technically from different individual parts.” CIO 7 restructured the IT organization by pooling all global resources and having all IT staff report centrally to the CIO again. The answers given by the interviewees show that a foundation for successful work as a CIO is the structure of the IT organization and its positioning in the context of the entire company. Hence, the positioning and restructuring of the IT organization is CSF #6.

4.2.3.3 CSF #7—Being a well-connected and communicative business leader

The results of the ranking of competencies show that technical competency plays a subordinate role for the interviewees. A frequently given reason for this was that “technology” is the responsibility of the direct reports with their staff. In contrast, respondents see leadership as a key competence. The CIOs emphasized above all the relevance of being connected and of communicating effectively. CIO 18 described the relevance of a good relationship: “before I have a technical discussion, I need to have built a relationship on a personal level.” Regarding communication, the most important aspect for CIO 4 was “communicating differently with each department and responding to their different thought patterns.” The results highlight the CIOs' aspirations to be accepted C-level executives and not just “Head of IT.” For these reasons, being a well-connected and communicative business leader is CSF #7.

4.2.4 Organizational environment (CSF #8 and #9)

4.2.4.1 CSF #8—Availability of skilled workforce

CIOs mentioned finding suitable staff as a major future challenge. “Getting the staff I need, with an appropriate amount of skill but also spirit” is the foundation for CIO 10. For CIO 18, staffing and competencies will play an important role in the future: “You have to decide which competencies you need, but the key competencies should be in-house. It will be interesting to see whether you find these skills on the market or develop them yourself.” In addition to developing new talents, “developing the existing team” was also an ongoing priority for CIOs 8 and 16. However, CIO 3 also pointed out that “IT is becoming a commodity and people are becoming more IT-savvy, so IT increasingly requires less expertise.” One of the ways IT executives are trying to address the availability of a skilled workforce is by further developing existing employees and by finding new employees through attractive work conditions. CIO 17, therefore, wanted to create an “environment and conditions that people will want to come to my organization.” The availability of a skilled workforce is, therefore, CSF #8.

4.2.4.2 CSF #9—Reporting line to the CEO

The respondents expressed the opinion that a CIO should also be a board member. CIO 6 and CIO 11 reported to the CFO at the beginning of their tenure, and both now report to the CEO. For CIO 6, “this allows for better governance.” For CIO 11, “this puts IT in an even better position, but does not influence the available budget.” While CIO 5 and CIO 9 believed that “a CIO should be a member of the board” or “must become part of the [executive] management team,” this plays a subordinate role for CIO 4, who stated, “if the CIO is not a member of the board, there needs to be an executive with a solid understanding of IT, and IT needs a strong voice on the board.” CIO 7 expressed the reporting line to the CEO and the relevance of participation in board meetings as follows: “If you report to the CFO, you do not sit in the board meetings. CFOs then report from it in the meetings with their direct reports. And often the strategically important topics for the CIO are then neglected.” To summarize, therefore, reporting line to the CEO is CSF #9.

4.3 CSF analysis

As part of the further analysis after CSF identification, we asked the participating CIOs to rank the identified CSFs. All 19 study participants provided a ranking. We applied Borda’s methods similarly as we did to analyze the interviews and used median (MED), arithmetic mean (ARM), geometric mean (GEM), and a special case of the p-norm (L2N) to analyze the ranking data. Table 15 shows the ranks of the aggregate functions and the respective ranks. The CSFs in the table are ordered by descending relevance. Overall, the ranking is rather consistent across the different aggregation methods.

With CSF#3 Anticipating the future through visionary thinking, CSF#2 Being perseverant to pursue long-term goals, and CSF#1 Accepting and embracing change, three out of four CSFs from the Personality category were rated as most relevant. This is followed by CSF #5 Cross-functional involvement and integration of the IT organization and CSF#7 Being a well-connected and communicative business leader from the Role Fulfilment category. With a ranking across aggregate functions, the last remaining CSF from the Personality category, CSF #4 Having empathy to deal with uncertainty felt by co-workers, is ranked at position six. The last remaining CSF from the Role Fulfilment category, CSF #6 Positioning and restructuring of the IT organization, follows in rank seven. The two CSFs from the Organizational Environment category, CSF #8 Availability of skilled workforce and CSF #9 Reporting line to the CEO, were rated least relevant.

Figure 14 shows the distribution of rankings per CSF. The CSFs are again ordered by descending relevance, and the figure shows the number of each ranking per CSF by the CIO panelists. To assess the group consensus, we calculated Kendall's W and found a low level of agreement (W = 0.248). In the nonparametric statistical approach, a weak agreement or consensus exists for W < 0.3; a moderate agreement for W = 0.5; and a strong agreement for W > = 0.7 (García-Crespo et al. 2010).

The figure illustrates the assigned relevance of the critical success factors by the interviewed CIOs. CSF #3 and CSF #1 were ranked first most often, six times each. In contrast, CSFs #4, #6, and #8 were not ranked first once. Especially for CSF #7 and CSF #4, a ranking with average relevance was chosen particularly frequently by the respondents. CSF #8 was assigned a low relevance, as eight CIOs ranked it second to last. CSF #9 shows a clear picture. More than half of the CIOs awarded the last ranking to that CSF. Nevertheless, five CIOs also disagree while ranking the CSF in the top three places.

In general, it can be seen that especially the CSFs from the Personality category are highly relevant from the perspective of the CIOs. According to the rankings, the Role Fulfilment category is also important for CIOs. Compared to the other two categories, the respondents attribute less relevance to the CSFs from the Organizational Environment category.

According to Kendall's W, there is only a low level of agreement within the group CIOs. However, when the CIOs provided us with their ranking, and some of them even gave additional free-text comments, they indicated that from their perspective, it is not adequate to rank the CSFs. For example, CIO 8 reasoned that “most of the CSF's are not particularly effective in isolation. It requires the combination of all the CSF's listed”. CIO 9 went on to say, “In the end, the given factors are interdependent and reinforce or weaken each other. In my opinion, a linear ranking is not very accurate.” Therefore, a low level of agreement seems to make sense, considering that the identified factors are already “critical” for success.

Furthermore, the participants confirmed the relevance of the identified CSFs. As CIO 17 said, “to be honest, really all factors are critical to success. However, a ranking is only helpful to a limited extent because only the balanced engagement with all factors can lead to success.” CIO 13 also stated, “these are all relevant CIO skills that are very difficult to put in order. Actually, the challenge is to balance all these competencies.” An interesting addition was made by CIO 2, who said, “a fixed ranking is actually not adequate, as the importance of a success factor depends, among other things, on the respective company context.”

In the discussion section, we will reflect upon these findings also in light of the descriptive results.

4.4 CSF management

In this section, we reflect on the managerial implications of the identified CSFs. These are relevant for CIOs themselves, their organizations, and CEOs or members of top management.

Some of the most important CSFs refer to personality traits (CSFs #3, #2, and #1). This is important for CIOs to keep in mind when executing their jobs. Personality traits are hard to develop or to acquire. However, regarding personality traits, CIO 17 also said, “you always have to be willing to evolve. You cannot change your environment; you can only change yourself. But by changing yourself, you can affect the environment and make it change.” Therefore, while it may help to sensitize CIOs to be aware of this need, it is even more relevant for organizations when they hire CIOs to look out for these personality traits, e.g., in candidate interviews and through examining track records from previous jobs.

CSF #5 and CSF#7, as part of the Role Fulfilment category, were ranked as similar but less important than the three personality traits (CSFs #3, #2, and #1). CIOs can more proactively address these two CSFs through modifying their management approach (CSF#7) and striving for a corresponding positioning of the IT organization. Again, CSF #7 can be a useful indication for CEOs when appointing a new CIO. Based on the mindset and prioritized competencies, management can assess whether the candidates consider themselves IT leaders or business leaders. To be a business leader, according to CIO 15, “an understanding of business strategy, business processes, and people is essential to successfully run IT.” Referring to being well-connected, CIO 5 emphasized that “even on issues that you could solve alone as a CIO, you should bring other colleagues on board to turn those affected into stakeholders.” This comment serves as an example of how CIOs can build relationships in their organizations. Apart from that, senior management members can help less experienced or newly appointed CIO colleagues build a network within the company.

CSF #5 resonates well with the notion of effective business-IT alignment. This CSF is also relevant for the top management team, as cross-functional involvement and integration require both the IT side and the business side to work together (Earl and Feeny 2000). CIOs consider cross-functional involvement and integration to be of high relevance. However, the involvement and integration demanded by CIOs must also be welcomed by the business side. If this is not the case, it is the responsibility of senior management to facilitate a common understanding and cooperation. If the level of cross-functional collaboration is advanced, it will affect the need for orchestrating the digital change (Haffke et al. 2016). According to CIO 9, the CIO role is particularly suited for this “because from this position, one has the best knowledge of the company—at least from a digital perspective.”

CSF #4 can play an important role, especially for organizations that want or need to make a major transformation. As CIO 8 expressed, “IT is the most important tool for change processes; change hardly works without IT.” However, change is always associated with uncertainty on the part of those affected. Management should pay particular attention to appointing an empathetic CIO during this process. Similar to CSF #3 and CSF #2, it is something for organizations to watch out for with potential new hires. Furthermore, CSF #4 falls under the personality category and can guide CIOs in developing themselves if they do not yet possess this skill.

Ranked seventh, CSF #6 might be less relevant because it is contingent on the state of the IT organization, thus resonating with CIO 2’s comment mentioned previously on CSF dependency. If repositioning is necessary, it is even more critical for success. If the positioning is already good, it seems to be more of a hygiene factor. Commenting on a successful positioning of IT, CIO 15 said, “IT must be part of the business as well as a partner of the business and not a subordinate service provider.” However, it is also evident that IT is not yet recognized as a strategic driver of value in their business by some companies (Peppard, 2010). Management must therefore work together with the CIO to establish the strategic orientation and positioning of IT.

CSFs #8 and #9 refer to the Organizational Environment category. The availability of a skilled workforce might be an unchangeable constraint, but our interviews also showed that CIOs can work toward headcount and/or budget increases if they align well within the top management team and/or the supervisory board. IT executives can also try to attract new employees through attractive work conditions. CIO 17, therefore, wanted to create an “environment and conditions that people will want to come to my organization.” Furthermore, if skills are lacking, CIOs can invest in developing skillsets their team needs in-house (Gefen et al. 2011). In this context, CIO 16 particularly wanted to “support and retain motivated and young talents.”

The reporting line is, among other things, an indicator of access to the top management team (Jones et al. 2020). CIO 7, as previously cited, vividly expressed the reporting line to the CEO and the relevance of participation in board meetings. However, the reporting line is dictated by the CEO. If the CIO and IT are to be better involved and represented in strategic decisions, it is the CEO's responsibility to establish this reporting line.

5 Discussion

In our study, we first descriptively analyzed various aspects related to the personality, role, and organizational environment of long-term CIOs. Based on interviews, we were able to identify nine CSFs in three categories. The participating CIOs ranked these factors to derive a perspective on the relative importance of these factors. To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first study analyzing CSF for long-term, i.e., successful, CIOs. Below, we discuss the key observations and implications of our study.

In some aspects, the descriptive results correspond to the CSF analysis; in other aspects, the descriptive results deviate from it. The three most relevant CSFs are each from the Personality category. Surprisingly, in the descriptive results, perseverance appeared to be ahead of visionary thinking, while this order is reversed in the CSF ranking. Almost two-thirds of the respondents stated that one of their greatest achievements was the positioning and restructuring of the IT organization. Ranked seventh in the CSF ranking, however, CSF #6 was assigned a rather low relevance. The descriptive results show that over half of the CIOs mentioned finding qualified staff as the biggest challenge for the future. However, the CIOs assigned a low relevance to CSF #8 in the later ranking. There is another deviation for CSF #9. The positioning of the CIO and thus the reporting line to the CEO or the membership in the management board was mentioned most often as a prerequisite for the success of the position. This CSF was, however, given a low relevance in the CSF ranking. Considering the verbal statements by the CIOs, our findings are consistent with the results by Armstrong and Sambamurthy (1999) as well as Preston and Karahanna (2008), that the information exchange in board meetings is more important than the actual reporting line. Especially the exchange of information on the part of both the CIO and management is easy to manage and can be improved if necessary. Therefore, the formal reporting line to the CEO does not seem to be decisive, but rather the result of better participation in discussions and involvement in strategic decisions.

In the Role Fulfilment category, the CIOs consider CSF #5 Cross-functional involvement and integration of the IT organization to be the most relevant. This shows how important IT executives consider it to be involved and present in all areas of the company. Therefore, in the bifurcation of the CIO role proposed by Chun and Mooney (2009), these CIOs could be classified under the “chief innovation officer” role, which is characterized by cross-functional integration as well as the responsibility of leveraging IT across multiple units within and outside the organization (Chun and Mooney 2009). Raising the profile and position of IT within the company thus remains an important aspect for CIOs (Chun and Mooney 2009). In this way, the IT organization can become the department that ties everything together and integrates into the entire organization (Gefen et al. 2011). However, CSF #6 Positioning and restructuring of the IT organization has not been ranked as particularly high by the CIOs. Nevertheless, the CEO and the CIO need a mutual understanding of the role and position of IT in the organization, and it is the CEO's responsibility to establish this role (Johnson and Lederer 2010).