Abstract

This paper investigates the predictive power of several risk attitude measures on a series of medical practices. We elicit risk preferences on a sample of 1500 French general practitioners (GPs) using two different classes of tools: scales, which measure GPs’ own perception of their willingness to take risks between 0 and 10; and lotteries, which require GPs to choose between a safe and a risky option in a series of hypothetical situations. In addition to a daily life risk scale that measures a general risk attitude, risk taking is measured in different domains for each tool: financial matters, GPs’ own health, and patients’ health. We take advantage of the rare opportunity to combine these multiple risk attitude measures with a series of self-reported or administratively recorded medical practices. We successively test the predictive power of our seven risk attitude measures on eleven medical practices affecting the GPs’ own health or their patients’ health. We find that domain-specific measures are far better predictors than the general risk attitude measure. Neither of the two classes of tools (scales or lotteries) seems to perform indisputably better than the other, except when we concentrate on the only non-declarative practice (prescription of biological tests), for which the classic money-lottery test works well. From a public health perspective, appropriate measures of willingness to take risks may be used to make a quick, but efficient, profiling of GPs and target them with personalized communications, or interventions, aimed at improving practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Physicians take risky decisions every day. Existing studies about medical practices provide evidence of heterogeneity regarding the choices that are made, even when differences due to patients’ characteristics are controlled for [1,2,3,4]. Several authors have emphasized the importance of factors related to the personal psychology of the physicians [5], and especially the interpersonal variability in dealing with risk and uncertainty [6, 7].

The medical literature has developed various instruments to capture the key elements of physicians’ behavior under risk and uncertainty. These instruments generally rely on psychometric scales and have various names, including “reaction to uncertainty”, “tolerance of/for ambiguity” and “risk preference” [8,9,10,11,12]. Economists have been traditionally quite skeptical toward these tools and have developed an extensive set of elicitation techniques, using binary lottery choice [13], unique choice among multiple lottery options [14, 15], or multiple price lists [16, 17]. The main advantage of these methods is that they are anchored in well-defined models of decision under risk (e.g., expected utility or prospect theory), where risk attitudes are directly derived from individual preferences characteristics (or axioms). In the context of health related national surveys, such tools have been used, but in a simplified form [18, 19]. Indeed, one drawback of the lottery-choice method is its relative complexity since it involves precise probabilistic information on monetary outcomes that are harder to address in a survey context, compared to an experimental set-up. Subjects may fail to understand the task, which could reduce the reliability of the risk preference measure and its predictive power [20]. For instance, Hellerstein et al. [21] conclude that lottery-choice measures of risk attitudes are unproven for predicting real world farming behavior. Similarly, Kapteyn and Teppa [22], Michela Coppola [23] and Lönnqvist et al. [24] find, in various contexts, that simple intuitive “a-theoretical” measures of risk preferences are more powerful predictors of behaviors than lottery-choice elicitations.

Given these results, simple psychometric scales of “willingness to take risks”, released from a strict theoretical background, have gained interest among economists. The validity of this type of measure has been confirmed by Dohmen et al. [25], using paid lottery choices as a gold standard. This movement has simplified the experimental apparatus necessary to elicit risk attitudes and has thus enabled researchers to extend the field of application of the measurement, i.e., to study risk attitude in larger samples but also outside the financial domain. Economists initially assumed that individuals exhibit a single risk preference, which governs risk-taking behavior in all contexts. This has been debated within the psychology literature and there is now quite large empirical evidence that risk attitude varies across different domains, as demonstrated using scales measuring risk attitudes in a wide range of domains, such as financial decisions, social decisions, health, leisure and career [25,26,27]. It has also been demonstrated using specifically designed lotteries. For instance, Prosser and Wittenberg [28] show that risk attitude varies across two domains: health and money. Attema et al. [29] obtain such variations when eliciting prospect theory in the health domain. Finally, van der Pol and Ruggeri [30] find that individuals’ risk attitude also varies depending on the outcomes considered in the health domain (life-years versus quality of life).

These observations motivate a general question about the best risk attitude measurement tool for predicting physicians’ behavior toward medical decisions. This broad-spectrum question can actually take two different forms: (1) Should the risk attitude measure be contextualized and, if so, what is the best context to consider? (2) What is the best method for eliciting risk preferences: lottery or scale? The present study attempts to provide elements of answers to these two questions. We take advantage of the unprecedented opportunity to combine several measurement tools of risk attitude, collected through a large sample of self-employed general practitioners (GPs) in France, with both self-reported and administratively recorded medical practices. We retain a series of eleven medical practices, whose purpose is to prevent or treat various health issues threatening the GPs themselves or their patients. For each of these practices, we successively test the predictive powerFootnote 1 of seven risk attitude measures. Four of them are scales and three are certainty equivalent elicitations obtained through successive binary lottery choices. Apart from a daily life risk scale that measures a general risk attitude, we designed these two classes of tools to be domain-specific to three important components of medical decision making: the GPs’ own health, the patients’ health and financial matters. This can be justified as follows. First, most GPs are their own treating physician, implying that they have to take risky decisions concerning their own health. Second, GPs are responsible for their patients’ health; as such, they are supposed to act with the intention of respecting others’ preferences regarding risk. Third, GPs earn their living as medical decision advisors, which necessarily introduces their financial risk attitude into the picture. This aspect is reinforced by the current context of increased judicialization of health care and of increased use of pay-for-performance schemes. In brief, we find that domain-specific measures are far better predictors than the general (daily life) measure, but that neither of the two classes of tools (scales and lotteries) performs indisputably better than the other.

Context and description of data

Context: the French health system for primary care

In France, GPs are the main primary care providers for more than 98% of the population. They are private, self-employed, and mostly remunerated using a fee-for-service system [31]. There is no ex ante assignment of the clientele to the primary care physician, so patients can self-select into the GPs, depending on their preferences and experiences with them. French GPs are in principle independent from the health insurer (the French Social Security and complementary health insurances) and lots of protection exists against the intervention of any insurers (private or public) into the medical decisions of physicians, whose quality of practices is rather regulated by “professional unions” or “health authorities” (Ordre des Médecins, Haute Autorité de Santé).Footnote 2 All in all, the French primary care system has been built to ensure a high level of professional autonomy, although it submits GPs to some financial risks (market uncertainty) and legal risks (judicialization). For this reason, we can hypothesize that the decision of the GP is essentially based on trade-offs between his professional motivations to practice good medicine, his own preferences for health, the belief he has in his patients’ preferences and—the subject of the present study—his attitudes toward risk in the health and monetary contexts.

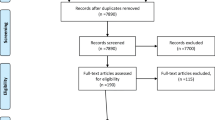

Sampling and procedure

The data used in this study come from a panel of French GPs designed to collect data regularly about their activity and practices. Composed of a national sample and three regional oversamples (Burgundy, Pays de la Loire and Provence-Alpes-Cote d’Azur), the French GPs panel was constituted in June 2010 through a partnership between the research department of the Ministry of Health, the regional health observatories and the representatives of self-employed GPs of the three regions mentioned above.

The sampling frame was obtained from the Ministry of Health’s exhaustive database of health professionals in France. GPs who had not received a fee of at least 1 euro during the year were excluded from the sampling frame, as well as physicians who were going to be stopping their activities or moving within 1 year, and those with a full-time practice in alternative medicine (e.g., acupuncture or homeopathy). Sampling was stratified for location of the general practice (urban, peri-urban, or rural areas), gender, age (<49, 49–56, >56 years old) and volume of activity [annual workload defined by the number of consultations and home visits: <2849 (Q1), 2849–5494 (Q2), >5494 (Q3)] in 2008.

Of the 6304 GPs who were contacted and eligible, 2496 (39.6%) agreed to participate in the panel, i.e., to respond to five consecutive surveys on different topics every 6 months. Professional investigators operated with computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) software and standardized questionnaires. Each GP received a monetary compensation equivalent to one consultation fee for each survey. To limit the selection bias that might have resulted from particular opinions or attitudes, the specific topics to be studied were not mentioned to GPs before they were asked to participate in the panel. The National Data Protection Authority (Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertés), responsible for ethical issues and protection of individual data in France, approved the panel and its procedures.

The GPs panel collected information through successive surveys starting in 2010. The fifth survey was completed in early 2013. This last wave collected opinions on “P4P reform” (module 1), “GPs/nurses delegation” (module 2) and “risk attitudes” (module 3). For this study, we focus on the 1568 GPs who were asked to answer the risk attitude questions.Footnote 3 All these GPs also participated in the first four cross-sectional surveys. “Appendix A” summarizes the sampling scheme and compares the sample with the target population.

Risk attitude measures

Propensity to take risks was measured using two different tools: scales and lotteries. For the former, we used four eleven-point self-reported Likert scale questions eliciting GPs’ willingness to take risks in four different contexts (in general in their daily life, for financial matters, for their own health and for their patients’ health). Literal translation of the questions asked by the interviewers is as follows (see “Appendix B” for the original French version):

In this question, you are asked to answer based on the perception you have of your personality. In the following domains, on a 0 to 10 scale, are you generally a person who is prepared to take risks or do you try to avoid risks?

- 1.

In general, in the different domains of your daily life, where do you situate yourself between 0 and 10, where 0 means “not at all willing to take risks” and 10 means “fully prepared to take risks”?

- 2.

For the management of your personal finance?

- 3.

Concerning your medical behavior involving the health of your patients?

- 4.

Concerning your medical behavior involving your own health?

For the lotteries, GPs were given iterative choices between two options, for two different domains. A first sequence of binary choices considers the financial domain and uses the standard monetary wording of lotteries (see “Appendix B” for the original French version):

Between the two following options, do you prefer:

Option A that gives you €40 with certainty;

or

Option B that gives you half a chance to gain €100 and half a chance to gain nothing.

This question was followed by two other successive binary choices, still in the financial domain, just modifying the sure amount of Option A, depending on GPs’ previous answers (see “Appendix C”).

A second gamble considers the health domain. Half of the GPs were interrogated about their own health and the other half about their patients’ health. The following wording was used (see “Appendix B” for the original French version):

Suppose that you are 70 years old and critically ill, if you had to choose for yourself between two therapies/for a 70-year-old patient who is critically ill, if you had to choose between two therapies, would you prefer:

Therapy A that gives you/him 4 additional life-years in good health;

or

Therapy B that gives you/him half a chance to gain 10 additional life-years in good health and half a chance to gain nothing.

Again, this question was followed by two other successive binary choices, in the health domain, just modifying the sure amount of Option A, depending on GPs’ previous answers (see “Appendix D”).

Thus, GPs were asked six binary lottery choices in total, and we were able to elicit two certainty equivalents for each GP: one in the financial domain (CEf), derived from the answers to the three chained monetary binary choices and giving the sure amount, in euros, such that CEf ~ (€100, ½; 0), where (€100, ½; 0) is the lottery giving €100 with half a chance and nothing otherwise and where ~ represents the indifference of the GP between the two options; and one in the health domain (CEh), derived from the answers to the three chained binary choices regarding either the patients’ health or the GP’s own health and giving the sure amount of life-years in good health such that CEh ~ (10Y, ½; 0), where (10Y, ½; 0) is the therapy giving half a chance to gain 10 additional life-years in good health and half a chance to gain nothing.

Medical practices data

Medical practices data come from the five cross-sectional surveys of the GPs panel (carried out over a period of 2.5 years). We identified ten practices in the questionnaires. Four of them concern the GP’s own health (self-reported):

-

1.

Being himself vaccinated against hepatitis B;

-

2.

Being himself vaccinated against 2009 influenza;

-

3.

Being himself vaccinated against pandemic influenza AH1N1;

-

4.

Having performed a lipid profile for himself in the last 3 years.

The six others concern the GP’s practices regarding his patients:

-

5.

Did the GP advise pandemic influenza vaccination AH1N1 to not-at-risk patients?

-

6.

Does the GP prescribe psychological therapy alone for mild-to-moderate depression very often?

-

7.

Did the GP propose to his last adult patient with asthma diagnosis to keep his follow-up booklet updated?

-

8.

Did the GP use a Rapid Antigen Diagnostic Test (RADT) in the last patient aged between 3 and 16 presenting with tonsillitis? (as recommended in French guidelines).

-

9.

Does the GP sometimes prescribe antibiotics to children with tonsillitis in case of a negative RADT result? (which is contrary to French guidelines).

-

10.

Does the GP occasionally practice alternative medicine (e.g., homeopathy or acupuncture)?

Practices 6 and 7 are reported using the context of a “vignette” (a clinical case, briefly described to the GP, followed by questions about their usual decision in that case—we relied on the approach suggested by Peabody et al. [32]).

These 10 practices were chosen among those available (themselves determined by the topics treated in the five surveys of the panel) to be as varied as possible in the large domain of decision under risk. They may imply a variety of trade-off deliberations, which will be described in Sect. “Prediction for each medical practice”.

Additional information from the RIAP

In addition to the information obtained through the cross-sectional surveys of the panel, we obtained annual data from the Individual Record of Activity and Prescriptions (RIAP) for each GP of the panel. It includes for each GP the total workload (total number of consultations and home visits, shortened in the following as “number of consultations”) and the characteristics of the clientele (proportion of patients younger than 16 years, proportion of patients older than 60 years, proportion of patients covered by the CMU, i.e., with free healthcare because of their low income, and proportion of patients exempt from payment because of long-term illness). It also contains records of all reimbursed spending for insured patients, especially the amount of biological tests prescribed by the GP (in value, measured as the sum of coefficients defined in the classification of medical procedures). In the analyses, we use the characteristics of the clientele as supplementary control variables and the amount of biological tests per consultation as an additional variable of medical practices (practice number 11).

Prediction for each medical practice

In this section, we conjecture about the channels that could drive the influence of risk attitudes in the 11 medical practices investigated in our analysis (described and numbered in the two previous sections). To this aim, we grouped them in three categories: vaccination (1, 2, 3, 5), uncertainty reduction (4, 7, 8, 10, 11) and defensive medicine (6, 9).

Vaccination typically implies a risk–benefit trade-off: perceived effectiveness of the vaccine and perceived likelihood of vaccine side effects are the two main predictors of shot acceptance [33]. If the expected gains of vaccination (both in monetary and health domains) outweigh the potential arms of side effects (individual and collective), we anticipate a risk-averse individual (and GP) to vaccinate more often (1, 2, 3) and to more frequently propose vaccination to patients (5) [34].

Practices 4, 8 and 11 reduce the uncertainty about diagnostics. Risk-averse GPs would be more likely to accept a cost in order to limit misdiagnosis and would therefore recommend such tests more frequently. Practice 7 can be considered similarly since it reduces uncertainty regarding the follow-up of asthma. In opposition, the use of alternative medicine (10), where scientific evidence is not assessed, tends to increase uncertainty. We would therefore expect risk-averse GPs to be less likely to favor such practices.

Defensive medicine occurs when practitioners perform a treatment or a procedure to avoid exposure to malpractice litigation. This could be the reason for prescription practices 6 and 9, defined by the strict observation of the official guidelines. One could argue that risk-averse GPs may be more prone to following official recommendations, which are also made to protect the patient.

Our expectations about the impact of the willingness to take risks on medical practices are summarized in Table 1. The variety of trade-off deliberations leads us, in the following, to test the predictive power of the competing domain-specific risk attitude measures without any a priori selection: every measure is tested as a potential predictor of every medical practice. Indeed, the stakes are often multidimensional, with both health and monetary consequences, and monetary costs can be supported by different actors: the patients, the GPs or society.

Methods

Our objective is to test the predictive power of our seven risk attitude measures (four scales and three certainty equivalents, each being taken separately) on eleven medical practices variables (ten categorical variables obtained from the GPs panel cross-sectional surveys and one continuous variable obtained from the RIAP). We conduct a set of regressions with the medical practices variables as dependent variables (logistic regressions for the ten two-level categorical variables and OLS regressions for the continuous variable) and the risk attitude metrics as individual explanatory variables, successively introduced in separate regressions (with the systematic use of the same set of controls). The four stratification variables, which account for the basic demographic characteristics of the GPs, are included as control variables (age as a continuous variable; the three others as categorical variables), as well as the characteristics of the clientele obtained in the RIAP (the four variables described in the previous section, converted into dummies indicating whether the value of each variable is greater than the mean).

Since our goal is to compare our seven risk attitude measures, we standardize all of them (same average, same standard deviation). We compare the predictive power of risk attitude measures firstly by domain and secondly by tool. For the comparison by domain, we concentrate on the scale variables because four different domains can be compared with this tool, while for certainty equivalents, only two domains are investigated in a within-subject analysis (the financial domain and one health domain). The comparison by tool is conducted within each available domain (finance, patient’s health and GP’s health). All reported coefficients are marginal effects. More precisely, for logistic regressions, they are average marginal effects. To compare the predictive power of the risk attitude variables, we first identify statistically significant coefficients, using the p-values. To compare several significant coefficients, we compare the size of the marginal effects and the R-squareds or (McFadden’s) pseudo R-squareds of the different regressions. We conduct the regressions strictly on the same samples for each medical outcome in order to be able to compare the pseudo R-squareds [35].

Another important methodological feature of our design is the “hypothetical” incentive scheme used in the elicitation tasks. In experimental economics, the chosen incentive mechanism might have a significant impact on the results [36,37,38]. In lottery choice tasks, hypothetical payment could bias participants’ elicited attitude in reducing their level of risk aversion [16, 39]. However, given our comparison’s approach between tools and domains, it was inconceivable to use real incentives, for the two following reasons. (1) First, the psychometric Likert scales cannot be incentivized within the revealed preference paradigm [25]. It would therefore be incorrect to compare this hypothetical measure, potentially prone to hypothetical bias, with an incentivized one (lotteries), as one could also argue that real incentives also reduce the noisiness of the data. (2) More fundamentally, the elicitation in the health domains (for self and for the patient) is an important topic of this paper and is anyway impossible to incentivize.Footnote 4 It would be incorrect to compare the predictive power of two lottery-based measures of risk attitudes, one being incentivized (in the money domain) and not the other (in the health domain). In fact, potential differences of performance could then be attributed to the hypothetical bias.

Finally, it should be noted that the results presented below are robust to controlling for self-assessed wealth and self-assessed health, which rules out the possibility that our results are driven by an endowment effect.

Results

Descriptive statistics of all variables used in this study are provided in Table 2. The sample consists of a majority of urban male GPs, with a mean age of 51 years.

Description of the GPs’ risk attitude

The response rate to scales is very high: missing data account for only 3–4% of the 1568 interrogated GPs in each context. For the lottery-choice questions, the response rate is lower: we are able to elicit a certainty equivalent for 71.8% (1126/1568) of GPs in the financial domain, 70.8% (556/785) in the patient’s health domain and 65.0% (509/783) in the GP’s health domain.

Results from the scales indicate an important variability in risk attitude according to the domain that is considered. GPs are less willing to take risks regarding their patients’ health (mean 3.3) and more willing to take risks regarding their own health (mean 5.1). Nebout et al. [40] provide a more detailed analysis of these results, especially by investigating the role of GPs’ demographic characteristics and providing possible causes and consequences of this discrepancy. Results from the lotteries indicate that 83.3% of GPs can be considered as risk averse (i.e., their certainty equivalent is lower than the expected payoff of the lottery—€50 or 5 years) in the financial domain, 88.2% are risk averse in the patient’s health domain and 76.1% in their own health domain. The ranking of domains in terms of intensity of risk aversion is thus similar with the two different tools. The risk attitude distributions for each tool in each domain are presented in “Appendix E”.

Table 3 displays the correlation table of the seven different risk attitude measures. The scale scores are more frequently correlated together, the highest correlation coefficient being between the financial and the daily life scales (0.44, p < 10−3). When considering the correlation between tools, the financial domain has the highest coefficient (0.18, p < 10−3). Surprisingly, there is no significant correlation between the GP’s health scale and the GP’s health certainty equivalent.

Predictive power of risk attitude measures: comparison by domain

The results are presented in Table 4.Footnote 5

Results concerning GPs’ own prevention practices

The daily life scale is never significant, whereas the contextualized risk scales are significant predictors of several medical practices. Three of the four GPs’ own prevention practices are significantly predicted by the GP’s health scale: vaccination against hepatitis B and seasonal influenza, and performance of a lipid profile. The two influenza vaccination attitudes are predicted by the financial scale. Unsurprisingly, the patient’s health scale is not a good predictor of the GP’s own prevention practices.

Results concerning patient-oriented medical practices

Again, the contextualized risk scales are significant predictors of several medical practices. First, and as expected, the patient’s health scale is a predictor of three out of seven medical practices: pandemic influenza vaccination advice (p < 0.1 only), no antibiotic prescription in case of negative RADT result and use of asthma booklet. Two of the seven practices are predicted by the financial scale: use of RADT and practice of alternative medicine. Two of the seven practices are explained by none of the scales: prescription of psychological therapy and the amount of biological tests. Surprisingly, the GP’s health scale is significant for two practices: use of RADT and practice of alternative medicine. For the latter, this could be explained by the fact that the GP could also use alternative medicine for his own health (the positive sign of the coefficient indicates that the more the GP is willing to take risks, the more he tends to practice alternative medicine). For these seven medical practices, except practice of alternative medicine, the daily life scale is never significant.

There are three medical practices for which several scales are significant predictors: vaccination against seasonal influenza, use of RADT and practice of alternative medicine. The marginal effects are close, implying that all significant scales perform equally well, except in the case of the practice of alternative medicine, where the financial scale performs a little better than the two others (daily life and GP’s health scales).

Predictive power of risk attitude measures: comparison by tool

The results are presented in Table 5. Since the response rate to lotteries is lower than the response rate to scales and since each health lottery was proposed to one half of the sample, the analyses are conducted on a smaller number of observations, which explains some discrepancies between Tables 4 and 5.

Results concerning GPs’ own prevention practices

For hepatitis B vaccination and performance of a lipid profile, none of the measures is significant. For vaccination against pandemic influenza, the financial scale is significant, as in Table 4, and is the only significant measure. The most interesting case concerns vaccination against seasonal influenza, where both financial measures are significant, as well as the certainty equivalent in the patient’s health domain. It is noteworthy that the GP’s health certainty equivalent is never significant (including the practice of alternative medicine, which the GP may use on himself).

Results concerning patient-oriented medical practices

The financial scale predicts the same two practices as in Table 4: use of RADT and practice of alternative medicine. The financial certainty equivalent predicts one important case: the amount of biological tests. In the patient’s health domain, both measures predict the use of the asthma booklet, but only the certainty equivalent predicts the prescription of psychological therapy. The GP’s health scale explains the use of RADT (as in Table 4), but none of the GP’s health certainty equivalents is significant (as expected). Two of the seven practices are not explained by any measures in any domains: pandemic influenza vaccination advice and no antibiotic prescription in the case of a negative RADT result.

Overall, there are two cases where both the scale and the certainty equivalent are significant: seasonal influenza vaccination in the financial domain, and the use of the asthma booklet in the patient’s health domain. In both cases, the magnitude of the two coefficients is close. Nevertheless, the scale performs a little better than the certainty equivalent in terms of predictive power in the first case and the certainty-equivalent metric performs a little better in the second case. There are three cases where the scales are significant while the certainty equivalents are not: pandemic influenza vaccination, use of a RADT and practice of alternative medicine (financial domain for all three). There are three cases where the certainty equivalents are significant while the scales are not: prescription of psychological therapy (patient’s health domain), seasonal influenza vaccination (patient’s health domain) and amount of biological tests (financial domain). This latter medical variable and its attached result will be discussed in more depth in the next section.

Discussion

This study is not the first one to establish a link between risk attitude and medical practices among physicians. For instance, Pearson et al. [12] find that physicians’ risk attitude as measured by a brief risk-taking scale correlates significantly with their rates of admission for emergency department patients with acute chest pain. Several studies [10, 41–43] show that selected physicians’ risk attitudes are correlated with the ordering of diagnostic tests and laboratory procedures, as well as with overall patient charges. Finally, using the same data set as the one used in this study but from a more medical point of view, Michel-Lepage et al. [44] find that risk-averse GPs use RADTs more often, and Massin et al. [34] that risk-averse GPs are more favorable toward influenza vaccination, than their more risk-tolerant colleagues. These two papers only use the risk attitude scales and adopt a dichotomous approach to risk attitude, by splitting the scale scores into two categories (risk-averse GPs from 0 to 5 and risk-tolerant GPs from 6 to 10).

This study is the first to examine the link between risk attitude and medical practices in a comparative way, using seven competing risk attitude measures, including certainty-equivalent metrics derived from binary lottery choices, and eleven medical practices, in a large sample. Our results indicate that domain-specific measures are the best predictors of the real-life decisions taken in their context. Hence, our results extend to the physician’s decision those of Weber et al. [26], showing that risk attitudes are highly domain-dependent, and those of Dohmen et al. [25] and Coppola [23], indicating that context-specific risk questions are the strongest risk measures for each context.

Our results also confirm our initial intuition that both health and financial considerations are often at stake when medical decisions are involved. For instance, we find that GPs’ self-vaccination against seasonal influenza is correlated with risk attitude measures in the financial domain, but also in the GP’s health and patient’s health domains. This seems to indicate that GPs who vaccinate themselves against seasonal influenza do it for a combination of reasons that may include: protecting their own health, protecting the health of their patients and avoiding sick leaves during an infection, which would lead to a loss of income.

Not surprisingly, we find a negative correlation between willingness to take risks and all prevention practices (being vaccinated and having performed a lipid profile). Regarding vaccination, the negative relationship suggests that GPs tend to perceive the costs of the illness to outweigh the potential risks and costs related to the vaccine. Besides, in the theoretical model of Picone et al. [45], the effect of a higher risk aversion on the propensity to make a test is shown to be ambiguous (risk-averse individuals balance the informational benefit of the test with the cost of the test, the cost of treatment and the probability of treatment being successful). Our results tend to suggest that in the case of a lipid profile test, the individual monetary cost of the treatment is perceived as relatively low—which is understandable bearing in mind the high reimbursement rates of the French social security system—and the efficiency of treatment is perceived as high.

In a first view, neither the scales nor the lotteries seem to perform indisputably better. Hence, in accordance with Charness et al. [20], it seems that choosing which tool to use is highly dependent on the question one wants to answer. Results from the GP’s health certainty equivalent are quite puzzling. Indeed, we noticed that it is not significantly correlated with the GP’s health scale and we then found that it predicts none of the medical practices considered. It is not clear why this metric performs so weakly. It can be noted that the response rate to the health domain lottery-choice questions is lower in the subsample concerned with GP’s health, compared with the subsample concerned with patient’s health (65.0 vs 70.8%, a two-tailed proportion test indicating that these proportions are statistically different with p = 0.014). This indicates that GPs had difficulties revealing their preferences for themselves. Especially, it might have been easier for them to consider life-year trade-offs for their patients rather than for themselves, simply because they are accustomed to the former situation in their daily practice. This problem (either strategic or cognitive) should be considered in future studies of this kind.

The eleven risky medical decisions, from the first to the last, cannot be predicted by a unique tool. This instability in the significance of the tools may leave us with the impression that we are not able to provide firm conclusions from the metrics comparison. Nevertheless, the nature of the variables invites us to make a hierarchy among the investigated medical practices. When dependent variables are self-reported medical practices (e.g., declared vaccination status or use of antibiotics), one could object that part of the correlation between the variables on both sides of the equation is nothing more than a common trait (an individual fixed-effect) in answering questions about risky behaviors. However, two variables are collected through clinical-case sketches (6 and 7) and one variable offers a measurement of a real practice, recorded by the social security system: the amount of biological tests prescribed per consultation. If we “believe” in this last variable more than in the other ones, the unique risk-attitude metric that seems to perform well is the classic money-lottery, a point which is worth mentioning, knowing the recent trend in the literature of pointing out the weak predictive validity of this kind of risk-attitude measure [21,22,23,24].

This study has some limitations that need to be mentioned. First, our experimental measures of risk attitude, based on lottery choices, are non-incentivized and may therefore be prone to a hypothetical bias. However, an important feature of our design was to ensure comparability across the three domains of risk-decision. Since it is impossible to incentivize life-years trade-off in the health domain, we preferred to do the same in the monetary domain. Second, we use a rather crude form of lottery choices (i.e., we use certainty equivalents directly as explanatory variables). This approach has, however, the advantage of not imposing particular utility-function assumptions. Third, while we have emphasized that some of our risk attitude measures make “qualitatively” correct predictions (i.e., are statistically significant), their quantitative effect is relatively small (only a small fraction of the variance of medical practices is explained by risk aversion). This is, however, a common feature of studies attempting to predict individual behavior [18]. Finally, we did not elicit the time preferences of GPs, which could be another explanatory variable of medical practices since they may be associated with real life risky behaviors [45, 46]. This issue is therefore left for further research.

Our paper can lead to recommendations for the public decision maker. In a public health perspective, appropriate measures of willingness to take risks may be used to make a quick (but efficient) profiling of GPs and target them with specific actions aimed at improving their medical practices. Communication about excessive exposure to danger, or (the reverse) too prudent practices, could be personalized for each GP detected with an atypical risk profile. Regarding the choice of the risk attitude measure to use in a survey, we find that different methods, or domains, have their own range of performance. Importantly, our general (i.e., non-contextualized daily life) risk scale is not a good predictor of medical practices. This departs from the result of Dohmen et al. [25], where the general risk question significantly explains each of the risky behaviors. This may be explained by the fact that Dohmen et al.’s study was conducted in the general population and analyzes common risky behaviors (portfolio choices, participation in sports, self-employment and smoking), while we study much more specific risky situations. Interestingly, our results also add to those of Prosser and Wittenberg [28], who found that research on risk preferences on monetary outcomes may not be an appropriate tool for risk preferences regarding health outcomes, considering the patient’s point of view. Our study shows that, considering the healthcare supplier’s point of view, the financial domain is still a reliable predictor of several medical practices. This is perfectly understandable since self-employed physicians often have to take economic motives into consideration (e.g., saving time is a permanent concern in the practice) [47]. This implies that the financial domain, elicited by binary lottery choices, should not be put aside too quickly when studying health decisions, particularly on the suppliers’ side.

Notes

In economic terms, French GPs are not concerned by the financial implications for the Social Security of their medical decisions. Their role of “gatekeeper” has not been associated with significant incentives on their side [48]. One limitation is that the physician has to agree to a national convention which makes it possible for their patients to be reimbursed by the public insurer for their consultations. But the convention is not really constraining in terms of medical practices. Recently, in 2012, a Pay for Performance system was deployed, but with limited impact on practices [49].

These 1568 GPs are part of the national sample (1052 respondents) and two regional oversamples: Burgundy (201 respondents) and Provence-Alpes Cote d’Azur (315 respondents). GPs of the Pays de la Loire oversample were not asked to answer the risk attitude questions because they were asked specific questions on local matters.

The proposed lotteries (therapies) are stylized objects that are not implementable in real life, for obvious practical and ethical reasons.

For space reasons, it was not possible to report the estimates for the control variables. In "Appendix F", we provide, by way of examples, comprehensive estimates for two regressions.

References

Wennberg, J., Gittelsohn, A.: Small area variations in health care delivery. Science 182, 1102–1108 (1973)

Corallo, A.N., Croxford, R., Goodman, D.C., Bryan, E.L., Srivastava, D., Stukel, T.A.: A systematic review of medical practice variation in OECD countries. Health Policy (New York) 114, 5–14 (2014). doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.08.002

Béjean, S., Peyron, C., Urbinelli, R.: Variations in activity and practice patterns: a French study for GPs. Eur. J. Health Econ. 8, 225–236 (2007). doi:10.1007/s10198-006-0023-4

Jaye, C., Tilyard, M.: A qualitative comparative investigation of variation in general practitioners’ prescribing patterns. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 52, 381–386 (2002)

Wennberg, J.E.: Dealing with medical practice variations: a proposal for action. Health Aff. 3, 6–32 (1984)

Eeckhoudt, L., Lebrun, T., Sailly, J.: Risk-aversion and physicians’ medical decision-making. J. Health Econ. 4, 273–281 (1985)

Eddy, D.M.: Variations in physician practice: the role of uncertainty. Health Aff. 3, 74–89 (1984). doi:10.1377/hlthaff.3.2.74

Gerrity, M.S., DeVellis, R.F., Earp, J.A.: Physicians’ reactions to uncertainty in patient care. A new measure and new insights. Med. Care 28, 724–736 (1990)

DeForge, B.R., Sobal, J.: Intolerance of ambiguity among family practice residents. Fam. Med. 23, 466–468 (1991)

Geller, G., Tambor, E.S., Chase, G.A., Holtzman, N.A.: Measuring physicians’ tolerance for ambiguity and its relationship to their reported practices regarding genetic testing. Med. Care 31, 989–1001 (1993)

Hancock, J., Roberts, M., Monrouxe, L., Mattick, K.: Medical student and junior doctors’ tolerance of ambiguity: development of a new scale. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 20, 113–130 (2015). doi:10.1007/s10459-014-9510-z

Pearson, S.D., Goldman, L., Orav, E.J., Guadagnoli, E., Garcia, T.B., Johnson, P.A., Lee, T.H.: Triage decisions for emergency department patients with chest pain: do physicians’ risk attitudes make the difference? J. Gen. Intern. Med. 10, 557–564 (1995)

Hey, J.D., Orme, C.D.: Investigating generalizations of expected utility theory using experimental data. Econometrica 62, 1291–1326 (1994)

Binswanger, H.P.: Attitudes toward risk: theoretical implications of an experiment in rural India. Econ. J. 91, 867 (1981). doi:10.2307/2232497

Eckel, C.C., Grossman, P.J.: Sex differences and statistical stereotyping in attitudes towards financial risk. Evol. Hum. Behav. 23, 281–295 (2002). doi:10.1016/S1090-5138(02)00097-1

Holt, C., Laury, S.: Risk aversion and incentive effects. Am. Econ. Rev. 92, 1644–1655 (2002)

Abdellaoui, M., Bleichrodt, H., L’Haridon, O.: A tractable method to measure utility and loss aversion under prospect theory. J. Risk Uncertain. 36, 245–266 (2008). doi:10.1007/s11166-008-9039-8

Barsky, R.B., Juster, F.T., Kimball, M.S., Shapiro, M.D.: Preference parameters and behavioral heterogeneity: an experimental approach in the health and retirement study. Quarterly J. Econ. 112, 537–579 (1997). doi:10.1162/003355397555280

Anderson, L.R., Mellor, J.M.: Predicting health behaviors with an experimental measure of risk preference. J. Health Econ. 27, 1260–1274 (2008). doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.05.011

Charness, G., Gneezy, U., Imas, A.: Experimental methods: eliciting risk preferences. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 87, 43–51 (2013). doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2012.12.023

Hellerstein, D., Higgins, N., Horowitz, J.: The predictive power of risk preference measures for farming decisions. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 40, 807–833 (2013). doi:10.1093/erae/jbs043

Kapteyn, A., Teppa, F.: Subjective measures of risk aversion, fixed costs, and portfolio choice. J. Econ. Psychol. 32, 564–580 (2011). doi:10.1016/j.joep.2011.04.002

Coppola, M.: Eliciting risk-preferences in socio-economic surveys: how do different measures perform? J. Socio. Econ. 48, 1–10 (2014). doi:10.1016/j.socec.2013.08.010

Lönnqvist, J., Verkasalo, M., Walkowitz, G.: Measuring individual risk attitudes in the lab: task or ask? An empirical comparison. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 119, 254–266 (2015). doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2015.08.003

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp, J., Wagner, G.G.: Individual risk attitudes: measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 9, 522–550 (2011). doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01015.x

Weber, E.U., Blais, A.-R., Betz, N.E.: A domain-specific risk-attitude scale: measuring risk perceptions and risk behaviors. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 15, 263–290 (2002). doi:10.1002/bdm.414

Hanoch, Y., Johnson, J.G., Wilke, A.: Domain specificity in experimental measures and participant recruitment. Psychol. Sci. 17, 300–304 (2006)

Prosser, L.A., Wittenberg, E.: Do risk attitudes differ across domains and respondent types? Med. Decis. Mak. 27, 281–287 (2007)

Attema, A.E., Brouwer, W.B.F., l’Haridon, O.: Prospect theory in the health domain: a quantitative assessment. J. Health Econ. 32, 1057–1065 (2013). doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.08.006

van der Pol, M., Ruggeri, M.: Is risk attitude outcome specific within the health domain? J. Health Econ. 27, 706–717 (2008). doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.10.002

Masseria, C., Irwin, R., Thomson, S., Gemmill, M., Mossialos, E.: Primary care in Europe. London Sch. Econ, London (2009). (Policy brief)

Peabody, J.W., Luck, J., Glassman, P., Dresselhaus, T.R., Lee, M.: Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA 283, 1715–1722 (2000)

Chapman, G.B., Coups, E.J.: Predictors of influenza vaccine acceptance among healthy adults. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 29, 249–262 (1999). doi:10.1006/pmed.1999.0535

Massin, S., Ventelou, B., Nebout, A., Verger, P., Pulcini, C.: Cross-sectional survey: risk-averse French general practitioners are more favorable toward influenza vaccination. Vaccine 33, 610–614 (2015). doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.12.038

Long, J.S.: Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks (1997)

Camerer, C.F., Hogarth, R.M.: The effects of financial incentives in experiments: a review and capital-labor-production framework. J. Risk Uncertain. 19, 7–42 (1999). doi:10.1023/A:1007850605129

Read, D.: Monetary incentives, what are they good for? J. Econ. Methodol. 12, 265–276 (2005). doi:10.1080/13501780500086180

Bardsley, N., Cubitt, R., Loomes, G., Moffatt, P., Starmer, C., Sugden, R.: Incentives in experiments. Experimental economics: rethinking the rules, pp. 244–285. Princeton University Press, Princeton (2009)

Beattie, J., Loomes, G.: The impact of incentives upon risky choice experiments. J. Risk Uncertain. 14, 155–168 (1997). doi:10.1016/S0167-6687(97)89209-8

Nebout, A., Cavillon, M., Ventelou, B.: Comparing GPs’ risk attitudes for their own health and for their patients’: a troubling discrepancy? BMC Health Serv. Res. (forthcoming)

Epstein, A.M., Begg, C.B., McNeil, B.J.: The effects of physicians’ training and personality on test ordering for ambulatory patients. Am. J. Public Health 74, 1271–1273 (1984)

Holtgrave, D.R., Lawler, F., Spann, S.J.: Physicians’ risk attitudes, laboratory usage, and referral decisions: the case of an academic family practice center. Med. Decis. Mak. 11, 125–130 (1991)

Allison, J.J., Kiefe, C.I., Cook, E.F., Gerrity, M.S., Orav, E.J., Centor, R.: The association of physician attitudes about uncertainty and risk taking with resource use in a Medicare HMO. Med. Decis. Mak. 18, 320–329 (1998)

Michel-Lepage, A., Ventelou, B., Nebout, A., Verger, P., Pulcini, C.: Cross-sectional survey: risk-averse French GPs use more rapid-antigen diagnostic tests in tonsillitis in children. BMJ Open. 3, e003540 (2013). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003540

Picone, G., Sloan, F., Taylor, D.: Effects of risk and time preference and expected longevity on demand for medical tests. J. Risk Uncertain. 28, 39–53 (2004). doi:10.1023/B:RISK.0000009435.11390.23

Khwaja, A., Silverman, D., Sloan, F.: Time preference, time discounting, and smoking decisions. J. Health Econ. 26, 927–949 (2007). doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.02.004

Kwietniewski, L., Heimeshoff, M., Schreyo, J.: Estimation of a physician practice cost function. Eur. J. Heal. Econ. (2016). doi:10.1007/s10198-016-0804-3

Dourgnon, P., Naiditch, M.: The preferred doctor scheme: a political reading of a French experiment of gate-keeping. Health Policy (New York) 94, 129–134 (2010). doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.09.001

Michel-Lepage, A., Ventelou, B.: The true impact of the French pay-for-performance program on physicians’ benzodiazepines prescription behavior. Eur. J. Health Econ. 17, 723–732 (2016). doi:10.1007/s10198-015-0717-6

Acknowledgements

We thank all GPs who participated in the survey as well as members of the supervisory committee of the French Panel of General Practices. The French Panel of General Practices received funding from Direction de la Recherche, des Etudes, de l’Evaluation et des Statistiques (DREES) — Ministère du travail, des relations sociales, de la famille, de la solidarité et de la ville, Ministère de la santé et des sports, through a multiannual agreement on objectives. Aix-Marseille School of Economics (Agence Nationale de la Recherche — Labex) also provided financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendices

Appendix A. Sampling scheme and comparison of the sample with the target population

Differences between the target population and the 1st survey sample of the panel are partly due to the use of specific inclusion criteria for entering the panel (notably, not planning to retire in the next 6 months, which explains, for instance, why there are fewer GPs older than 56 in the panel than in the target population). Attrition does not seem to be an issue since there are no statistically significant differences between the sample used in the statistical analysis of this paper and the sample of the first survey of the panel. A more detailed analysis of the 54 strata (obtained by combining the 4 stratification variables) indicates that significant differences (between the sample used in the analysis and the target population) can be found in 12 of them. Although we cannot exclude a selection bias, it is likely to be limited.

Appendix B. Questionnaire: original French version

a. Elicitation of risk attitude using scales.

Pour cette question, il vous est demandé de répondre en fonction de la perception que vous avez de votre propre caractère. Dans les domaines suivants, sur une échelle de 0 à 10, êtes-vous plutôt une personne prête à prendre des risques ou essayez-vous de ne pas en prendre ?

- 1.

En général, dans les différents domaines de la vie quotidienne, où vous situez-vous entre 0 et 10, 0 correspondant à pas du tout disposé à prendre des risques et 10 à entièrement prêt à prendre des risques ?

- 2.

Pour la gestion de vos finances personnelles ?

- 3.

S’agissant de vos comportements médicaux impliquant la santé de vos patients ?

- 4.

S’agissant de vos comportements médicaux impliquant votre propre santé ?

b. Elicitation of risk attitude using lotteries.

Dans les questions suivantes, des situations de choix mettant en jeux des options incertaines vont vous être présentées. Il vous est demandé de choisir entre deux options (A ou B) comme vous le feriez si vous étiez réellement confronté à la situation de choix décrite.

Nous insistons sur le fait qu’il n’y pas de bonne ou de mauvaise réponse.

Nous allons tout d’abord vous proposer des choix dont les conséquences sont monétaires.

Entre les deux options suivantes, préférez-vous:

L’option A qui vous donne 40 € de façon certaine;

ou

L’option B qui vous donne 1 chance sur 2 de gagner 100 € et 1 chance sur 2 de ne rien gagner.

Maintenant nous allons vous proposer des choix dont les conséquences portent sur votre santé/la santé de vos patients.

Etant âgé de 70 ans et gravement malade, si vous deviez choisir pour vous-même entre deux thérapies/pour un patient âgé de 70 ans et gravement malade, si vous deviez choisir entre deux thérapies, préféreriez-vous:

La thérapie A qui vous/lui donne 4 années de vie en bonne santé de façon certaine;

ou

La thérapie B qui vous/lui donne 1 chance sur 2 de gagner 10 années de vie en bonne santé et 1 chance sur 2 de ne rien gagner.

Appendix C. Structure of binary choices used to elicit the certainty equivalent in the financial domain (CE f )

Boxed numbers represent the sure amount offered in option A. This amount is €40 for every respondent in the first question. It is then iteratively modified depending on the choice of the respondent in the former question.

Option B is a lottery giving €100 with half a chance and nothing otherwise (€100, ½; 0). It remains identical for all questions.

Example of CEf calculation: the first binary choice is between €40 for sure (choice A) and the lottery giving €100 with half a chance and nothing otherwise (choice B). If the respondent chooses A, i.e., €40 for sure, he then has to choose between €20 for sure (choice A) and the same lottery (choice B). Suppose that he chooses B, i.e., the lottery, then the last binary choice is between €30 for sure (choice A) and the lottery (choice B). If he chooses B again, then we consider that CEf equals €35, which corresponds to the middle of the interval where the respondent switches from the sure gain to the lottery.

Appendix D. Structure of binary choices used to elicit the certainty equivalent in the health domain (CEh)

Boxed numbers represent the sure amount offered in option A. This amount is 4 additional life-years in good health for every respondent in the first question. It is then iteratively modified depending on the choice of the respondent in the former question.

Option B is a lottery giving 10 additional life-years in good health with half a chance and nothing otherwise (10Y, ½; 0). It remains identical for all questions.

Appendix E. Percent frequency distribution of risk attitude for each tool in each domain

Appendix F. Comprehensive estimates for two regressions

The table below provides comprehensive estimates for two regressions chosen as examples among the 110 regressions conducted in this paper. In the first column, the dependent variable is “The GP is himself vaccinated against seasonal influenza” and the risk attitude explanatory variable is the GP’s health scale. In the second column, the dependent variable is the logarithm of the average amount of biological tests prescribed per consultation and the risk attitude explanatory variable is the financial certainty equivalent. The coefficient estimates for the main explanatory variables can be found in Tables 4 (for the seasonal influenza vaccination regression) and 5 (for the biological tests regression). The aim of the appendix is to provide the coefficient estimates for all control variables. As explained in the “Method” section, a logistic regression was used in the case where the dependent variable is vaccination against seasonal influenza since it is a binary variable, and average marginal effects are reported. An OLS regression was used for the biological tests regression since it is a continuous variable.

Dependent variable: the GP is vaccinated against seasonal influenza (logistic regression; average marginal effects) | Dependent variable: logarithm of the average amount of biological tests prescribed per consultation (OLS regression) | |

|---|---|---|

Risk attitude measured with the GP’s health scale | −0.025** (0.023) | |

Risk attitude measured with the financial certainty equivalent | −0.024** (0.046) | |

Male | 0.037 (0.135) | −0.121*** (0.000) |

Age | −0.000 (0.872) | −0.005*** (0.001) |

Location of practice (ref. rural) | ||

Peri-urban | 0.053 (0.138) | −0.026 (0.503) |

Urban | 0.023 (0.456) | 0.013 (0.705) |

Volume of activity (ref. <2849) | ||

2949–5494 | 0.128** (0.000) | 0.123*** (0.000) |

>5494 | 0.155*** (0.000) | 0.112*** (0.002) |

Proportion of patients younger than 16 years > mean | 0.037 (0.140) | −0.201*** (0.000) |

Proportion of patients older than 60 years > mean | −0.015 (0.559) | 0.086*** (0.002) |

Proportion of patients covered by the CMU > mean | −0.065** (0.020) | −0.149*** (0.000) |

Proportion of patients exempted from payment > mean | 0.024 (0.368) | 0.120*** (0.000) |

Constant | 0.520 (0.292) | 3.759 (0.000) |

R-squared/pseudo R-squared | 0.033 | 0.133 |

Number of observations | 1475 | 1087 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Massin, S., Nebout, A. & Ventelou, B. Predicting medical practices using various risk attitude measures. Eur J Health Econ 19, 843–860 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-017-0925-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-017-0925-3