Abstract

There are nowadays over 1 million Portuguese who lack a primary care physician. By applying a discrete choice experiment to a large representative sample of Portuguese junior doctors (N = 503) in 2014, we provide an indication that this shortage may be addressed with a careful policy design that mixes pecuniary and non-pecuniary incentives for these junior physicians. According to our simulations, a policy that includes such incentives may increase uptake of general practitioners (GPs) in rural areas from 18% to 30%. Marginal wages estimated from our model are realistic and close to market prices: an extra hour of work would require an hourly wage of 16.5€; moving to an inland rural setting would involve an increase in monthly income of 1.150€ (almost doubling residents’ current income); a shift to a GP career would imply an 849€ increase in monthly income. Additional opportunities to work outside the National Health Service overcome an income reduction of 433€. Our simulation predicts that an income increase of 350€ would lead to a 3 percentage point increase in choice probability, which implies an income elasticity of 3.37, a higher estimation compared to previous studies.

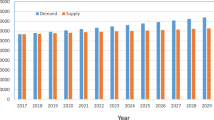

Source: own elaboration using Tableau Software® (NYSE: DATA) with data from Statistics Portugal (INE; https://www.ine.pt)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In this study, we use the terms “GP” and “family doctor” interchangeably.

In this hyperlink we provide an animated visualization with the population-adjusted geographic dispersion of medical doctors in Portugal, according to their medical specialty. (http://public.tableau.com/profile/pedro.jorge.saldanha.ramos#!/vizhome/DispersoGeogrficadeMdicos/Planilha1). Data Source: Health Human Resources Database, Statistics Portugal, 2011.

Primary care is publicly financed and publicly delivered, which means there are no GP cooperatives or independently working physicians financed by the State. There is a legal framework for (private) physician cooperatives to contract primary care services for a specific population, yet this model (known as Family Health Unit type C) has never been implemented.

This is the base salary doctors receive in the NHS, for a 35-40 h/week contract.

The IMF issued a report last year where it presented some figures about doctors’ and nurses’ wages in Portugal and a comparison with other European countries. The report was severely criticized by the PMA and there is no compelling evidence for using those estimates in our study.

β coefficients were set to zero in the pilot survey since information about the direction of preferences in the Portuguese context is nonexistent.

Minimizing D-error is the most common criterion for evaluating DCEs [40].

This 10th choice scenario was only used as an exclusion criterion and not for estimating the model.

Interacting these attributes with other socio-demographic or medical education variables in a standard logit is unlikely to fully capture preference heterogeneity since some of it may be dependent only on unobservable characteristics (e.g., prejudice or prestige related to a specific specialty/location, specific moral values, etc.).

Standard logit is a specific case where the mixing distribution is degenerate at 0 and 1.

There is an ongoing debate over the benefits and problems of estimating WTP in preference space (described in the text) and in WTP space (where the model’s coefficients directly represent the WTP measures). We compared our model estimates in preference and WTP spaces and found no significant differences between them (data not shown, available upon request). Our models in preference scale have produced very realistic WTP estimates (see below), so we stick with this more widespread methodology [44].

We used this method to account for any asymmetric WTP distributions [48].

We chose to apply on-site paper questionnaires instead of the easier online modality in order to increase our response rates. We are grateful to our colleagues working at each hospital for helping us with the logistics behind administering a national-level paper-based survey.

In the supplemental information, we provide the Stata code for this simulation procedure.

In a separate model (data not shown, available upon request), we included “private work” and “income” as correlated variables, to test whether junior doctors pictured those variables as substitutes. We did not find a statistically significant correlation, which implies that the utility gained from having more “private work” is not just related to income factors, but has a value per se.

In Table 5, we show that the MWTP for “Work hours” is 66€. Converting the monthly salary into a weekly amount, we have 66€/4 = 16,5€.

On Table 7 we show that Policy I predicts that an income increase of 350€ would lead to a 3 p.p. increase in choice probability. Therefore \((\partial { \Pr }\;({\text{Rural GP}})/\partial \;{\text{income}}) \, ({\text{income}}/{ \Pr }({\text{Rural GP}}) = (0.0 3/ 3 50) \times ( 2 7 50/0.0 7) = 3. 3 7.\)

References

Newhouse, J.P.: Geographic access to physician services. Annu. Rev. Public Health 11(1), 207–230 (1990). doi:10.1146/annurev.pu.11.050190.001231

Gachter, M., Schwazer, P., Theurl, E., Winner, H.: Physician density in a two-tiered health care system. Health Policy 106(3), 257–268 (2012). doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.04.012

Kristiansen, I.S., Forde, O.H.: Medical specialists’ choice of location: the role of geographical attachment in Norway. Soc. Sci. Med. (1982) 34(1), 57–62 (1992)

Nicholson, S.: Physician specialty choice under uncertainty. J. Labor Econ. 20(4), 816–847 (2002)

Baumgardner, J.R.: The division of labor, local markets, and worker organization. J. Political Econ. 96(3), 509–527 (1988)

Theodorakis, P., Mantzavinis, G., Rrumbullaku, L., Lionis, C., Trell, E.: Measuring health inequalities in Albania: a focus on the distribution of general practitioners. Hum. Resour. Health 4(1), 5 (2006)

Unal, E.: How the government intervention affects the distribution of physicians in Turkey between 1965 and 2000. Int. J. Equity Health 14(1), 1 (2015). doi:10.1186/s12939-014-0131-1

Póvoa, L., Andrade, M.V.: Distribuição geográfica dos médicos no Brasil: uma análise a partir de um modelo de escolha locacional. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 22, 1555–1564 (2006)

Mantzavinis, G., Theodorakis, P.N., Lionis, C., Trell, E.: Geographical inequalities in the distribution of general practitioners in Sweden. Lakartidningen 100(51–52), 4294–4297 (2003)

Gravelle, H., Sutton, M.: Inequality in the geographical distribution of general practitioners in England and Wales 1974–1995. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 6(1), 6–13 (2001)

Bodenheimer, T., Pham, H.H.: Primary care: current problems and proposed solutions. Health Aff. (Project Hope) 29(5), 799–805 (2010). doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0026

Ono, T., Schoenstein, M., Buchan, J.: Geographic imbalances in doctor supply and policy responses. OECD Publishing, Paris (2014)

Nigenda, G.: The regional distribution of doctors in Mexico, 1930–1990: a policy assessment. Health Policy 39(2), 107–122 (1997). doi:10.1016/S0168-8510(96)00864-0

Matsumoto, M., Inoue, K., Bowman, R., Noguchi, S., Kajii, E.: Physician scarcity is a predictor of further scarcity in US, and a predictor of concentration in Japan. Health Policy 95(2–3), 129–136 (2010). doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.11.012

Grobler, L., Marais, B.J., Mabunda, S.A., Marindi, P.N., Reuter, H., Volmink, J.: Interventions for increasing the proportion of health professionals practising in rural and other underserved areas. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (2009). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005314.pub2

Santana, P., Peixoto, H., Loureiro, A., Costa, C., Nunes, C., Duarte, N.: Estudo de evolução prospectiva de médicos no Sistema Nacional de Saúde. Ordem dos Médicos, Lisboa (2013)

Santana, P., Peixoto, H., Duarte, N.: Demography of physicians in Portugal: prospective analysis. Acta Médica Portuguesa. 27(2) 246–251 (2014)

Correia, I., Veiga, P.: Geographic distribution of physicians in Portugal. Eur. J. Health Econ. HEPAC Health Econ. Prev. Care 11(4), 383–393 (2010). doi:10.1007/s10198-009-0208-8

Decree-Law 101/2015. In: Health, M. (ed.). Lisbon

Ministerial Order 54/2010. In: Health, M. (ed.). Lisbon

Roeger, L.S., Reed, R.L., Smith, B.P.: Equity of access in the spatial distribution of GPs within an Australian metropolitan city. Aust. J. Prim. Health 16(4), 284–290 (2010). doi:10.1071/py10021

ADHA: Australia’s medical workforce. In: Ageing, A.D.O.H.A. (ed.). Australia (2005)

García-Pérez, M.Á., Amaya, C., López-Giménez, M.R., Otero, Á.: Distribución geográfica de los médicos en España y su evolución temporal durante el período 1998–2007. Revista Española de Salud Pública 83, 243–255 (2009)

Wanzenried, G., Nocera, S.: The evolution of physician density in Switzerland. Swiss J. Econ. Stat. (SJES) 144(II), 247–282 (2008)

Goddard, M., Gravelle, H., Hole, A., Marini, G.: Where did all the GPs go? Increasing supply and geographical equity in England and Scotland. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 15(1), 28–35 (2010). doi:10.1258/jhsrp.2009.009003

Günther, O.H., Kürstein, B., Riedel-Heller, S.G., König, H.-H.: The role of monetary and nonmonetary incentives on the choice of practice establishment: a stated preference study of young physicians in Germany. Health Serv. Res. 45(1), 212–229 (2010). doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01045.x

Gagné, R., Léger, P.T.: Determinants of physicians’ decisions to specialize. Health Econ. 14(7), 721–735 (2005). doi:10.1002/hec.970

Thornton, J., Esposto, F.: How important are economic factors in choice of medical specialty? Health Econ. 12(1), 67–73 (2003). doi:10.1002/hec.682

Scott, A.: Eliciting GPs’ preferences for pecuniary and non-pecuniary job characteristics. J. Health Econ. 20(3), 329–347 (2001)

Scott, A., Witt, J., Humphreys, J., Joyce, C., Kalb, G., Jeon, S.-H., McGrail, M.: Getting doctors into the bush: general practitioners’ preferences for rural location. Soc. Sci. Med. 96, 33–44 (2013)

Ubach, C., Scott, A., French, F., Awramenko, M., Needham, G.: What do hospital consultants value about their jobs? A discrete choice experiment. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 326(7404), 1432 (2003). doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1432

Sivey, P., Scott, A., Witt, J., Joyce, C., Humphreys, J.: Junior doctors’ preferences for specialty choice. J. Health Econ. 31(6), 813–823 (2012). doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.07.001

Hancock, C., Steinbach, A., Nesbitt, T.S., Adler, S.R., Auerswald, C.L.: Why doctors choose small towns: a developmental model of rural physician recruitment and retention. Soc. Sci. Med. (1982) 69(9), 1368–1376 (2009). doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.002

Steele, M.T., Schwab, R.A., McNamara, R.M., Watson, W.A.: Emergency medicine resident choice of practice location. Ann. Emerg. Med. 31(3), 351–357 (1998). doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(98)70346-4

Jarman, B.T., Cogbill, T.H., Mathiason, M.A., O’Heron, C.T., Foley, E.F., Martin, R.F., Weigelt, J.A., Brasel, K.J., Webb, T.P.: Factors correlated with surgery resident choice to practice general surgery in a rural area. J. Surg. Educ. 66(6), 319–324 (2009). doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2009.06.003

Holte, J.H., Kjaer, T., Abelsen, B., Olsen, J.A.: The impact of pecuniary and non-pecuniary incentives for attracting young doctors to rural general practice. Soc. Sci. Med. 1982(128), 1–9 (2015). doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.022

Kolstad, J.R.: How to make rural jobs more attractive to health workers. Findings from a discrete choice experiment in Tanzania. Health Econ. 20(2), 196–211 (2011). doi:10.1002/hec.1581

Barros, P.P., Machado, S.R., Simoes Jde, A.: Portugal. Health system review. Health Syst. Transit 13(4), 1–156 (2011)

Crabbe, M., Vandebroek, M.: Using appropriate prior information to eliminate choice sets with a dominant alternative from D-efficient designs. J. Choice Model. 5(1), 22–45 (2012). doi:10.1016/S1755-5345(13)70046-0

Kuhfeld, W.F., Tobias, R.D., Garratt, M.: Efficient experimental design with marketing research applications. J. Mark. Res. 545–557 31(4), (1994)

Decree-Law 68/2008. In: Government, P. (ed.). Lisbon

Comission Regulation (EU) No 31/2011. In: EU (ed.). Brussels

Hole, A.R.: Modelling heterogeneity in patients’ preferences for the attributes of a general practitioner appointment. J. Health Econ. 27(4), 1078–1094 (2008). doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.11.006

Hole, A.R., Kolstad, J.R.: Mixed logit estimation of willingness to pay distributions: a comparison of models in preference and WTP space using data from a health-related choice experiment. Empir. Econ. 42(2), 445–469 (2011). doi:10.1007/s00181-011-0500-1

Fiebig, D.G., Knox, S., Viney, R., Haas, M., Street, D.J.: Preferences for new and existing contraceptive products. Health Econ. 20(Suppl 1), 35–52 (2011). doi:10.1002/hec.1686

Fiebig, D.G., Keane, M.P., Louviere, J., Wasi, N.: The generalized multinomial logit model: accounting for scale and coefficient heterogeneity. Mark. Sci. 29(3), 393–421 (2010). doi:10.1287/mksc.1090.0508

Gu, Y., Hole, A.R., Knox, S.: Fitting the generalized multinomial logit model in Stata. Stata J. 13(2), 382–397 (2013)

Hole, A.R.: A comparison of approaches to estimating confidence intervals for willingness to pay measures. Health Econ. 16(8), 827–840 (2007). doi:10.1002/hec.1197

De Souza, J.C., Sardinha, A.M., Sanchez, J.P.Y., Melo, M., Ribas, M.J.: Os cuidados de saúde primários e a medicina geral e familiar em Portugal. Revista Portuguesa de Saúde Pública 2, 63–74 (2001)

Grol, R., Giesen, P., van Uden, C.: After-hours care in the United Kingdom, Denmark, and The Netherlands: new models. Health Aff. 25(6), 1733–1737 (2006). doi:10.1377/hlthaff.25.6.1733

Smits, M., Huibers, L., Oude Bos, A., Giesen, P.: Patient satisfaction with out-of-hours GP cooperatives: a longitudinal study. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 30(4), 206–213 (2012). doi:10.3109/02813432.2012.735553

Lagarde, M., Pagaiya, N., Tangcharoensathian, V., Blaauw, D.: One size does not fit all: investigating doctors’ stated preference heterogeneity for job incentives to inform policy in Thailand. Health Econ. 22(12), 1452–1469 (2013). doi:10.1002/hec.2897

Wong, S.F., Norman, R., Dunning, T.L., Ashley, D.M., Lorgelly, P.K.: A protocol for a discrete choice experiment: understanding preferences of patients with cancer towards their cancer care across metropolitan and rural regions in Australia. BMJ Open 4(10), 1–9 (2014). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006661

Reed Johnson, F., Lancsar, E., Marshall, D., Kilambi, V., Mühlbacher, A., Regier, D.A., Bresnahan, B.W., Kanninen, B., Bridges, J.F.P.: Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis experimental design good research practices task force. Value Health 16(1), 3–13 (2013). doi:10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2223

Li, J., Scott, A., McGrail, M., Humphreys, J., Witt, J.: Retaining rural doctors: doctors’ preferences for rural medical workforce incentives. Soc. Sci. Med. 121, 56–64 (2014). doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.053

Acknowledgements

We are deeply indebted to our colleagues and friends at several medical schools and hospitals across the country for helping us with the logistics for distributing and collecting the questionnaires, particularly to the following MDs: Ana Rita Ramos, André Graça, André Tojal, Bernardo Matias, Carina Mendonça, Carolina Cardoso, Carolina Carneiro, Diogo Dias, Eduardo Palha Fernandes, Elisabete Ribeiro, Flávio Costa, João Felgueiras, João Lopes, João Neves, João Rego, João Sousa, José Pedro Pinto, Luís Coutinho, Luís Magalhães, Luísa Graça, Manuel Abecasis, Margarida Bernardo, Mariana Carrapatoso, Nélson Cunha, Nídia Ramos, Nuno China, Nuno Morais, Ricardo Reis, Ricardo Veiga, Rita Ferreira, Rui Coelho, Rui Malheiro, Rui Lopes. We are also thankful to Antonio Monforte for his initial guidance with the SAS algorithm, and to Professor Rita Gaio for the help with the model analysis. We are also grateful to ACSS, I.P. for valuable statistics of the population of junior doctors our sample represented. We acknowledge valuable feedback from the participants at the 14th Health Economics’ Portuguese Conference and at the European Health Economics Association conference (EuHEA 2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ramos, P., Alves, H., Guimarães, P. et al. Junior doctors’ medical specialty and practice location choice: simulating policies to overcome regional inequalities. Eur J Health Econ 18, 1013–1030 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-016-0846-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-016-0846-6