Abstract

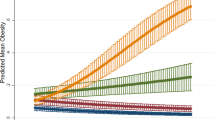

In this paper, we examine the role of relative food prices in determining the recent increase in body weight in Italy. Cross-price elasticities of unhealthy and healthy foods estimated by a demand system provide a consistent framework to evaluate substitution effects, when a close association is assumed between unhealthy (healthy) foods and more (less) energy-dense foods. We used a dataset constructed from a series of cross-sections of the Italian Household Budget Survey (1997–2005) to obtain the variables of the demand system, which accounts for regional price variability. The relative increase in healthy food prices was found to produce nontrivial elasticities of substitution towards higher relative consumption of unhealthy foods, with effects on weight outcomes. In addition, these changes were unevenly distributed among individuals and were particularly significant for those who were poorer and had less education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A cohort approach has been used to estimate the relationship between household food consumption and obesity in France [4].

Recent research programs have also used scanner data from grocery stores to estimate price elasticities, with observation of prices paid for individual transactions. Although within-category substitution of food would be much more meaningful as consumers can substitute more easily towards similar goods, it is doubtful whether this segmentation would lead to more effective policy implications. With the plethora of food products on offer, many items are generally not consumed by households, so that the problem of possible inefficiencies in implementing food policies to reduce the frequency of overweigh, while recognised in the literature, needs to be resolved. One way of doing this would involve modelling the zero expenditure of households.

Clearly, many other factors have been analysed in the literature to investigate the direct effects on food consumption. A very important, although short list of these factors includes changes to the food environment Morland et al. [5], advertising Chou et al. [6] and nutrition labelling Kuchler et al. [7]

For a review of longitudinal studies of socio-economic status and weight, see Ball and Crawford [13].

The body mass index (BMI) is a measure of body fat based on height and weight, which applies to both adult men and women. Four categories are generally used to classify adults: (1) Underweight BMI ≤ 18.5; (2) Normal weight = 18.5–24.9; (#) Overweight = 25–29.9; (4) Obesity = 30 or over. It is known that BMI is not the most accurate measure of body fat and that self-reported weight produces measurement errors for young and adult people. For a critical discussion of this indicator, see Burkhauser and Cawley [21].

See Cranfield and Pellow [28] for a more thorough discussion of the role of global and local negativity in functional form selection.

In order to remark the properties of the demand system, the AIDS provide a reasonablly accurate approximation at any set of prices not too far from the point of approximation.

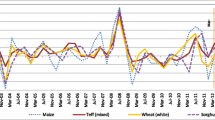

Results of formal tests of non-stationarity with the FDFGLS test of Elliot et al. [38] and KPSS of Kwiatkowski et al. [39] for the full sample and subsamples are not presented here, but they are consistent with the hypothesis that budget shares (and also prices and real expenditure) contain unit roots. Both estimations and graphs of budget share subsample patterns are available upon request.

In a complete demand system, we should consider previously at least the choice of how to allocate total expenditure between goods and services for consumption [41].

To select the order of the VAR, we used the sequential modified likelihood ratio (LR) test as in Lütkepohl [44], while estimations are carried out by including centred seasonal dummies.

The third cointegrating vector for other foods and non-durables is then recovered by the adding-up constraint.

The differences in the results of the theoretical restriction tests are emphasised when small sample statistics are performed. In this case, although the model estimated with a national price index is still rejected at 1%, data that use a regional price index do not reject homogeneity and symmetry at 5%. These results are available upon request.

Typically, one chooses this point to hold concavity because it is the point with the highest sample “information” and the data are scaled consequently. Asymptotic standard errors of elasticities and confidence intervals are derived from bootstrap replications of the estimated parameters and their standard errors.

The results of a greater propensity towards healthy food purchases find indirect confirmation by the greater control of women’s weight with respect to those recorded for men and by the low perception of being underweight of Italian women. These findings are in line with those obtained in France [17, 47].

It is worth noting that these results obtained for the sample of less educated individuals were computed by averaging the growth of each group from 1999/2000 to 2005.

An implicit reason exists for the ineffectiveness of unhealthy taxation of energy-dense foods, determined by market competition in developed countries. As discussed by Powell and Chaloupka [3], the presence of large quasi-competitive non-taxed high-calorie foods sold by groceries can potentially substitute taxed foods, making the impact on individual or aggregate body weight limited or irrelevant.

The Italian Minister for Economy and Finance stated that in 2007, there were about 1,300,000 indigent people which were eligible for the “social card”, and over 7,400,000 poor individuals were estimated to be below the poverty line in the same year. A first ex-post evaluation reports that only 42% of indigent people complied with the “social card” program.

References

Kopelman, P.G.: Obesity as a medical problem. Nature 404, 635–643 (2000)

Lakdawalla, D., Philipson, T.: The growth of obesity and technological change. Econ. Hum. Biol. 7, 283–293 (2009)

Powell, L.M., Chaloupka, F.J.: Food prices and obesity: evidence and policy implications for taxes and subsidies. Milbank Q. 87(1), 229–257 (2009)

Bonnet, C., Dubois, P., Orozco, V.: Food consumption and obesity in France. Paper presented at INRA-IDEI Workshop on Economics of Obesity Toulouse, 12–13 December (2008)

Morland, K., Roux, A., Wing, S.: Supermarkets, other food stores, and obesity. Am. J. Prevent. Med. 30(4), 333–339 (2006)

Chou, S., Grossman, M., Saffer, H.: An economic analysis of adult obesity: results from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. J. Health Econ. 23, 565–587 (2004)

Kuchler, F., Golan, E., Variyam, J., Crutchfield, S.: Obesity policy and the law of unintended consequences. Amber Waves 3, 26–33 (2005)

Costa-Font, J., Fabbri, D., Gil, J.: Decomposing body mass index gaps between Mediterranean countries: a counterfactual quantile regression analysis. Econ. Hum. Biol. 7, 351–365 (2009)

ISTAT: Annual multipurpose survey of Households “Aspetti della vita quotidiana” Roma (2007)

Cutler, D.M., Glaeser, E.L., Shapiro, J.M.: Why have Americans become more obese? J. Econ. Perspect. 17(3), 93–118 (2003)

Auld, M.C., Powell, L.M. Economics of food energy density and adolescent body weight. Economica (2009, forthcoming)

Zheng, X., Zhen, C.: Healthy food unhealthy food and obesity. Econ. Lett. 100, 300–303 (2008)

Ball, K., Crawford, D.: Socioeconomic status and weight change in adults: a review. Soc. Sci. Med. 60, 1987–2010 (2005)

Klesges, R., Ward, K., Ray, A., Cutter, G., Wagenknecht, L.: The prospective relationships between smoking and weight in a young biracial cohort: the coronary artery risk development in young adults study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 66, 987–993 (1998)

Dennis, B.H., Pajak, A., Pardo, B., Davis, C.E., Williams, O.D., Piotrowski, W.: Weight gain and its correlates in Poland between 1983 and 1993. Int. J. Obes. 24, 1507–1513 (2000)

Hardy, R., Wadsworth, M., Kuh, D.: The influence of childhood weight and socioeconomic status on change in adult body mass index in a British national birth cohort. Int. J. Obes. 24, 725–734 (2000)

DeSaint Pol, T.: Evolution of obesity by social status in France 1981–2003. Econ. Hum. Biol. 7, 398–404 (2009)

Villar, J.G., Quintana-Domeque, C.: Income and body mass index in. Eur. Econ. Hum. Biol. 7(1), 73–83 (2009)

Bray, G.A.: Overweight is risking fate: definition classification prevalence and risks. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 499, 14–28 (1987)

Gelbach, J.B., Klick, J., Stratmann, T.: Cheap donuts and expensive broccoli: relative price effects on body mass index. Working Paper Florida State University (2007)

Burkhauser, R.V., Cawley, J.: Beyond BMI: the value of more accurate measures of fatness and obesity in social science research. J. Health Econ. 27(2), 519–529 (2008)

Chesher, A.: Individual demands from household aggregates: time and age variation in the composition of diet. J. Appl. Econometr. 13, 505–524 (1998)

Drewnowski, A., Darmon, N.: Food choices and diet costs: an economic analysis. The American society for nutritional sciences. J. Nutr. 135, 900–904 (2005)

Deaton, A.S., Muellbauer, J.: An almost ideal demand system. Am. Econ. Rev. 70, 312–326 (1980)

Muellbauer, J.N.: Community preferences and the representative consumer. Econometrica 44, 979–999 (1976)

Deaton, A.S.: Demand analysis. In: Griliches, Z., Intriligator, M.D. (eds) Handbook of econometrics, vol. 3, 1767–1839 (1986)

Barnett, W.A., Serletis, A.: Consumer preferences and demand systems. J. Econometr. 147, 210–224 (2008)

Cranfield, J.A.L., Pellow, S.: The role of global vs local negativity in functional form selection: an application to Canadian consumer demands. Econ. Modell. 21, 345–360 (2004)

Attfield, C.: Estimating a cointegrated demand system. Eur. Econ. Rev. 41, 61–73 (1997)

Attfield, C.: Stochastic trends demographics and demand systems. University of Bristol mimeographs (2004)

Lewbel, A., Ng, S.: Demand systems with nonstationary prices. Rev. Econ. Stat. 87, 479–494 (2005)

Pesaran, M.H.: The role of economic theory in modelling the long-run. Econ. J. 107(440), 178–191 (1997)

Johansen, S.: Identifying restrictions of linear equations with applications to simultaneous equations and cointegration. J. Econometr. 69, 111–132 (1995)

Pesaran, M., Shin, Y.: Long-run structural modelling. Econometr. Rev. 21, 49–87 (2002)

Coondoo, D., Majumder, A., Ray, R.: Method of calculating regional consumer price differentials with illustrative evidence from India. Rev. Income Wealth 50(1), 51–68 (2004)

Ng, S.: Testing for homogeneity in demand systems when the regressors are nonstationary. J. Appl. Econometr. 10, 147–163 (1995)

Lewbel, A.: Consumer demand systems and household equivalence scales. In: Pesaran, M.H., Wickens, M.R. (eds.) Handbook of Applied Econometrics, pp. 167–196. Blackwell: Oxford (1999)

Elliott, G., Rothenberg, T.J., Stock, J.H.: Efficient tests for an autoregressive unit root. Econometrica 64, 813–836 (1996)

Kwiatkowski, D., Phillips, P.C.B., Schmidt, P., Yongcheol Shin, Y.: Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root. J. Econometr. 54, 159–178 (1992)

Edgerton, D.L.: Weak separability and the estimation of elasticities in multistage demand systems. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 79, 62–79 (1997)

Gorman, W.M.: Separability and aggregation. In: Blackorby, C., Shorrocks, A. (eds.) Editors Collected Works of W.M. Gorman, Vol. 1. Clarendon Press, Oxford (1995)

Hicks, J.R.: A revision of demand theory. Oxford University Press, Oxford (1936)

Allen, R.G.D.: Mathematical analysis for economists. Macmillan, London (1938)

Lütkepohl, H.: Introduction to multiple time series analysis. Springer, Berlin (1991)

Saikkonen, P., Lütkepohl, H.: Trend adjustment prior to testing for the cointegrating rank of a VAR process. J. Time Ser. Anal. 21, 435–456 (2000)

Conforti, P., Pierani, P., Rizzi, P.L.: Food and nutrient demands in Italy actual behaviour and forecast through a multistage quadratic system with heterogeneous preferences. Working Paper 303 Univerity of Siena (2001)

Etile, F.: Social norms ideal body weight and food attitudes. Health Econ. 16, 945–966 (2007)

Baum, C.L.: The effects of race ethnicity and age on obesity. J. Populat. Econ. 20, 687–705 (2007)

Komlos, J., Baur, M.: From the tallest to (one of) the fattest: the enigmatic fate of the American population in the 20th century. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2(1), 57–74 (2004)

Chouinard, H., Davis, D., LaFrance, J., Perloff, J.: Fat taxes: big money for small change. Forum Health Econ. Policy 10, 2 (2007)

Lin B-H, Guthrie, J.F.: How do low-income households respond to food prices? In: Can Food Stamps Do More to Improve Food Choices? An Economic Perspective Economic Information Bulletin Number 29-5. US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, Washington, DC (2007)

Guthrie, J., Frazao, E., Andrews, M., Smallwood, D.: Improving food choices can food stamps do more? Amber Waves 5(2), 22–28 (2007)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants at the “8th Annual International Conference on Health Economics, Management and Policy”, 27–30 June, 2009, Athens, Greece, at the 50th “Conference of the Societ Italiana degli Economisti”, 22–24 October 2009, Rome at the “5th Nordic Econometric Meeting”, 29–31 October 2009, Lund, Sweden and at the “24th Annual Conference of the European Society for Population Economics”, 9–12 June, 2010 Essen, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

see Table 6.

Appendix 2: Identification of long-run AIDS

The cointegration relationships in the VECM equation (6), subject to reduced rank restrictions on the \(\Uppi=\alpha \beta^{\ast^{\prime }}\) matrix, are not identified. Following Pesaran and Shin (2002), the identification of the long-run parameters in \(\beta^{\ast ^{\prime }}\) requires the imposition of r restrictions on each cointegrating vector, although a necessary and sufficient condition (order condition) for the identification is that the number of the identifying restrictions, k, should be at least equal to r 2.

In order to explain these fundamental identifying conditions in our demand system with three categories of goods, we note first that adding up reduces the rank to two, i.e., r = (n − 1). As a formal extension of the ECM vectors in Eq. (6), let us consider two non-identified cointegrating vectors made up of the variables w 1t , w 2t , lnP 1t , lnP 2t , lnP 3t , ln(y t /p t ) and the intercept. The associated parameters are as follows:

The exact identifying restrictions r 2 = (n − 1)2 = 4 assume a diagonal structure because theory suggests that budget shares responds mainly respond to own and cross-price changes and income impulses, but not to (endogenous) changes in other budget shares. Formally,

so that the cointegrating vectors may be written as:

In order to test theoretical restrictions, long-run parameter restrictions should be included. As discussed in the text, the property of symmetry may be imposed as a cross-equation restriction, β32 = β41. The cointegrating vectors thus assume the following structure:

Estimations of cointegrating vectors subject to symmetry is tested by the LR statistic distributed as a χ2 with one degree of freedom. This restriction is not rejected when the log likelihoods of this restricted model is compared with the exact-identified model in Eq. (13), the differences are not significant.

Lastly, as suggested by the demand theory, we impose and test in the cointegration vectors the properties of both symmetry and homogeneity. In addition to the symmetry restriction, β32 = β41, the restriction of homogeneity for each equation is added, that is, (β31 + β32 = −β51) and (β32 + β42 = −β52). Thus, the cointegration vector is given as:

As shown in the text, the LR statistic, distributed as a χ2 with three degrees of freedom, is then used to test these joint theoretical restrictions.

Appendix 3

see Table 7.

Appendix 4

see Table 8.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pieroni, L., Lanari, D. & Salmasi, L. Food prices and overweight patterns in Italy. Eur J Health Econ 14, 133–151 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-011-0350-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-011-0350-y