Abstract

Background

The use of smoking cessation medications can considerably enhance the long-term abstinence rate at a reasonable cost, but only a small proportion of quitters seek medical assistance. The objective of this study was to evaluate the factors that influence the decision to use such treatments and the willingness-to-pay of smokers for improved cessation drugs.

Method

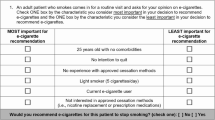

A discrete choice experiment was conducted amongst smokers in the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Choice sets consisted of two hypothetical medications described via five attributes (price, efficacy, possibility of minor side effects, attenuation of weight gain and availability) and an opt-out option. Various discrete choice models were estimated to analyse both the factors that influence treatment choice and those that influence the overall propensity to use a smoking cessation medication.

Results

Our results indicate that smokers are willing to pay for higher efficacy, less-frequent side effects and prevention of weight gain. Whether the drug is available over-the-counter or on medical prescription is of secondary importance. In addition, we show that there are several individual-specific factors influencing the decision to use such medications, including education level. Results also indicate substantial preference heterogeneity.

Conclusion

This study shows that there is a potential demand for improved cessation medications. Broader usage could be reached through lower out-of-pocket price and greater efficacy. Secondary aspects such as side effects and weight gain should also be taken into consideration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In 2007, 54% of Swiss smokers wanted to quit, but only 10% within the next 30 days and 30% within the next 6 months [2].

NRTs partially relieve the withdrawal symptoms that people experience when they quit, by compensating for the lack of nicotine in the organism. There are several NRTs currently available over-the-counter in Switzerland, including patches, gum, inhalers, lozenges and nasal sprays.

Two nicotine-free medications are available in Switzerland by medical prescription only (A list): bupropion (brand name Zyban®), whose exact mode of action is still unclear [6], and varenicline (brand name Champix®), which relieves symptoms of nicotine withdrawal and blocks the reinforcing effect of continued nicotine use through an antagonist and agonist action [7].

Also known as alternative-specific choice experiments. DCEs that use generic titles for the alternatives are called unlabelled DCEs, contrary to labelled choice experiments, where each alternative refers to a particular commodity (e.g., Zyban®) [31].

The perceived value of quitting is defined as “the difference between the lifetime utility from quitting and the lifetime utility from continuing to smoke” (Avery et al. [28]).

For instance, if we compare two medications, one that has a lower price, higher efficacy and fewer side-effects, with the other attributes being at the same level, is considered dominant.

IIA holds in the same nest but not across different nests.

In short, draws from \( f(\beta \left| \theta \right.) \) are used to get a simulated value of the log-likelihood function. This is done for different values of θ, until we obtain the maximum simulated likelihood (Train [50]).

In order to assess potential non-linearity within these attributes, a MNL model was also estimated using the levels of the attributes in the utility function (the levels were effects coded [31]). Results, available upon request, show that the linearity assumption is reasonable.

The IV parameter associated with the opt-out option was set to one.

This method, which is also referred to as parametric bootstrap, consists of taking draws from a multivariate normal distribution with means and covariance given by the estimated coefficients and the associated variance–covariance matrix. Here, we performed 10,000 draws to obtain 10,000 values of the coefficients from the joint distribution. We used these values to compute 10,000 mWTP estimates for each non-price attribute. The 95% confidence interval is then defined by taking the upper and lower 2.5 percentiles of the distribution.

References

Swiss Federal Statistical Office: Les décès dus au Tabac en Suisse. Estimation Pour les Années Entre 1995 et 2007. Swiss Federal Statistical Office, Neuchâtel (2009)

Keller, R., Radtke, T., Krebs, H., Hornung, R.: Der Tabakkonsum der Schweizer Wohnbevölkerung in den Jahren 2001 bis 2009. Tabakmonitoring–Schweizerische Umfrage zum Tabakkonsum. Psychologisches Institut der Universität Zürich. Sozial- und Gesundheitspsychologie, Zürich (2010)

Joosens, L., Raw, M.: The tobacco control scale (TCS): a new scale to measure country activity. Tob Control 15, 247–253 (2006)

Fiore, M.: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependance, Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline. US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD (2000)

Wu, P., Wilson, K., Dimoulas, P., Mills, E.J.: Effectiveness of smoking cessation therapies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 6, 300 (2006)

Compendium suisse des médicaments. Documed AG, Basel (2002)

Gonzales, D., Rennard, S.I., Nides, M., Oncken, C., Azoulay, S., Billing, C.B., Watsky, E.J., Gong, J., Williams, K.E., Reeves, K.R.: Varenicline, an α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-released bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation. JAMA 296, 47–55 (2006)

Berchi, C., Dupuid, J.-M., Launoy, G.: The reasons of general practitioners for promoting colorectal cancer mass screening in France. Eur. J. Health Econ. 7, 91–98 (2006)

Brau, R., Bruni, M.L.: Eliciting the demand for long-term care coverage: a discrete choice modelling analysis. Health Econ. 17, 411–433 (2008)

Ryan, M., Netten, A., Skatun, D., Smith, P.: Using discrete choice experiments to estimate a preference-based measure of outcome—An application to social care for older people. J. Health Econ. 25, 927–944 (2006)

Zweifel, P., Telser, H., Vaterlaus, S.: Consumer resistance against regulation: the case of health care. J. Regul. Econ. 29, 319–332 (2005)

Kerssens, J.J., Groenewegen, P.: Consumer preferences in social health insurance. Eur. J. Health Econ. 29, 319–332 (2005)

Ryan, M., Hughes, J.: Using conjoint analysis to assess women’s preferences for miscarriage management. Health Econ. 6, 261–273 (1997)

Hall, J., Kenny, P., King, M., Louviere, J., Viney, R., Yeoh, A.: Using stated preference discrete choice modelling to evaluate the introduction of varicella vaccination. Health Econ. 11, 457–465 (2002)

Aristides, M., Weston, A.R., FitzGerald, P., Reun, C.L., Maniadakis, N.: Patient preference and willingness-to-pay for Humalog Mix25 relative to Humulin 30/70: A multicountry application of a discrete choice experiment. Value Health 7, 442–454 (2004)

Mark, T.L., Swait, J.: Using stated preference modeling to forecast the effect of medication attributes on prescriptions of alcoholism medications. Value Health 6, 474–482 (2003)

Marshall, D.A., Johnson, F.R., Phillips, K.A., Marshall, J.K., Thabane, L., Kulin, N.A.: Measuring patient preferences for colorectal cancer screening using a choice-format survey. Value Health 10, 415–430 (2007)

Roux, L., Ubach, C., Cam, : Valuing the benefits of weight loss programs: An application of the discrete choice experiment. Obes. Res. 12, 1342–1351 (2004)

Bryan, S., Buxton, M., Sheldon, R., Grant, A.: Magnetic resonance imaging for the investigation of knee injuries: an investigation of preferences. Health Econ. 7, 595–603 (1998)

Watson, V., Ryan, M., Brown, C.T., Barnett, G., Ellis, B.W., Emberton, M.: Eliciting prefenrences for drug treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J. Urol. 172, 2321–2325 (2004)

Bertram, M.Y., Lim, S.S., Wallace, A.L., Vos, T.: Costs and benefits of smoking cessation aids: making a case for public reimbursement of nicotine replacement therapy in Australia. Tob. Control. 16, 255–260 (2007)

Cornuz, J., Gilbert, A., Pinget, C., McDonald, P., Slama, K., Salto, E., Paccaud, F.: Cost-effectiveness of pharmacotherapies for nicotine dependence in primary care settings: a multinational comparison. Tob. Control. 15, 152–159 (2006)

Hall, S.M., Lightwood, J.M., Humfleet, G.L., Bostrom, A., Reus, V.I., Munoz, R.: Cost-effectiveness of Bupropion, Nortriptyline, and psychological intervention in smoking cessation. J. Behav. Health Ser R. 32, 381–392 (2005)

Warner, K.: Cost-effectiveness of smoking-cessation therapies—interpretation of the evidence and implications for coverage. Pharmacoeconomics 11, 538–549 (1997)

Tauras, J.A., Chaloupka, F.J.: The demand for nicotine replacement therapies. Nicotine Tob. Res. 5, 237–243 (2003)

Keeler, T.E., Hu, T.-W., Keith, A., Manning, R., Marciniak, M., Ong, M., Sung, H.-Y.: The benefits of switching smoking cessation drugs to over-the-counter status. Health Econ. 11, 389–402 (2002)

Halpin, H.A., McMenamin, S.B., Shade, S.B.: The demand for health insurance coverage for tobacco dependence treatments: Support for a benefit mandate and willigness to pay. Nicotine Tob. Res. 9, 1269–1276 (2007)

Avery, R., Kenkel, D., Lillard, D.R., Mathios, A.: Private profits and public health: does advertising of smoking cessation products encourage smokers to quit? J. Polit. Econ. 115, 447–481 (2007)

Busch, S.H., Falba, T.A., Duchovny, N., Jofre-Bonet, M., O’Malley, S.S., Sindelar, J.L.: Value to smokers of improved cessation products: Evidence from a willingness-to-pay survey. Nicotine Tob. Res. 6, 631–639 (2004)

Paterson, R.W., Boyle, K.J., Parmeter, C.F., Neumann, J.E., Civita, P.D.: Heterogeneity in preferences for smoking cessation. Health Econ. 17, 1363–1377 (2008)

Hensher, D.A., Rose, J.M., Greene, W.H.: Applied Choice Analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2005)

Lancaster, K.J.: A new approach to consumer theory. J. Polit. Econ. 74, 132–157 (1966)

McFadden, D.: Econometric models of probalistic choice. In: Manski, C., McFadden, D. (eds.) Structural Analysis of Discrete Choice Data with Economic Applications, pp. 422–434. MIT Press, Boston (1981)

Ryan, M., Gerard, K., Amaya–Amaya, M.: Using discrete choice experiments to value health and health care. Springer, Dordrecht (2008)

Peters, M.J., Morgan, L.C.: The parmacotherapy of smoking cessation. Med. J. Aust. 176, 486–490 (2002)

Henningfield, J.E., Fant, R.V., Buchalter, A.R., Stitzer, M.L.: Pharmacotherapy for nicotine dependance. Cancer J. Clin. 55, 281–299 (2005)

Jorenby, D.E., Hays, J.T., Rigotti, N.A., Azoulay, S., Watsky, E.J., Williams, K.E., Billing, C.B., Gong, J., Reeves, K.R.: Efficacy of varenicline, an α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation. JAMA 296, 56–63 (2006)

McEwen, A., West, R., Owen, L.: GP prescribing of nicotine replacement and bupropion to aid smoking cessation in England and Wales. Addiction 99, 1470–1474 (2004)

Froom, P., Melamed, S., Benbassat, J.: Smoking cessation and weight gain. J. Fam. Pract. 46, 460–464 (1998)

Klesges, R., Winders, S., Meyers, A., Eck, L., Ward, K., Hultquist, C.: How much weight gain occurs following smoking cessation? A comparison of weight gain using both continuous and point prevalence abstinence. J. Consult. Clin. Psych. 65, 286–291 (1997)

Williamson, D., Madans, J., Anda, R., Kleinman, J., Giovino, G., Byers, T.: Smoking cessation and severity of weight gain in a national cohort. New Engl. J. Med. 324, 739–745 (1991)

Meyers, A.W., Klesges, R.C., Winders, S.E., Ward, K.D., Peterson, B.A., Eck, L.H.: Are weight concerns predictive of smoking cessation? A prospective analysis. J. Consult Clin. Psych. 65, 448–452 (1997)

Ryan, M., Skatun, D.: Modelling non-demanders in choice experiments. Health Econ. 13, 397–402 (2004)

Sloane, N.J.A.: A library of orthogonal arrays. http://www.research.att.com/~njas/oadir/ (2007). Accessed Dec 2007

Street, D.J., Burgess, L.: The construction of optimal stated choice experiments. Wiley, Hoboken (2007)

Burgess, L.: Discrete choice experiments (computer software), Department of Mathematical Sciences, University of Technology, Sydney, http://crsu.science.uts.edu.au/choice/ (2007). Accessed Jan 2011

Lancsar, E., Louviere, J.: Deleting ‘irrational’ responses from discrete choice experiments: a case of investigating or imposing preferences. Health Econ. 15, 797–811 (2006)

Miguel, F.S., Ryan, M., Amaya–Amaya, M.: ‘Irrational’ stated preferences: a quantitative and qualitative investigation. Health Econ. 14, 307–322 (2005)

McFadden, D.: Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In: Zarembka, P. (ed.) Frontiers in Econometrics, pp. 105–142. Academic Press, New-York (1974)

Train, K.E.: Discrete choice methods with simulation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2003)

Louviere, J.J., Hensher, D.A., Swait, J.D.: Stated Choice Methods. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2000)

Ryan, M., Major, K., Skatun, D.: Using discrete choice experiments to go beyond clinical outcomes when evaluating clinical practice. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 11, 328–338 (2005)

Haefen, R.H.V., Massey, D.M., Adamowicz, W.: Serial nonparticipation in repeated discrete choice models. Am. J. Agr. Econ. 87, 1061–1076 (2005)

Hausman, J., McFadden, D.: Specification tests for the multinomial logit model. Econometrica 52, 1219–1240 (1984)

Hole, A.R.: A comparison of approaches to estimating confidence intervals for willingness to pay measures. Health Econ. 16, 827–840 (2007)

Krinsky, I., Robb, A.: On approximating the statistical properties of elasticities. Rev. Econ. Stat. 72, 189–190 (1986)

Hole, A.R.: Modelling heterogeneity in patients’ preferences for the attributes of a general practitioner appointment. J. Health. Econ. 27, 1078–1094 (2008)

Kjaer, T., Bech, M., Gyrd-Hansen, D., Hart-Hansen, K.: Ordering effect and price sensitivity in discrete choice experiments: Need we worry. Health Econ. 15, 1217–1228 (2006)

Krebs, H., Keller, R., Radtke, T., Hornung, R.: Raucherberatung in der ärztlichen und zahnmedizinischen Praxis aus Sicht der Rauchenden und ehemals Rauchenden (Befragung 2009). Tabakmonitoring—Schweizerische Umfrage zum Tabakkonsum. Psychologisches Institut der Universität Zürich, Sozial- und Gesundheitspsychologie, Zürich (2010)

Mentzakis, E., Ryan, M., McNamee, P.: Using discrete choice experiment to value informal care tasks: exploring preference heterogeneity. Health Econ. (2010). doi:10.1002/hec.1656

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marti, J. Assessing preferences for improved smoking cessation medications: a discrete choice experiment. Eur J Health Econ 13, 533–548 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-011-0333-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-011-0333-z