Abstract

This paper presents parameter estimates for physician service equations using the “European Community Household Panel” for 12 countries covering the period 1994–1996. The focus is on two specific points: (1) the identification of behavioural similarities and differences in the demand for health services across the 12 countries; (2) the variability in demand for health services represented through a joint model for all countries. We found that there are significant differences among countries, although there are also similarities in the effect of variables such as health stock, labour situation or family structure. An important fraction of the variability in the demand for health services across countries could be explained by differences in age, income and the role of general practitioners as gatekeepers in the public health system. We found some evidence of induced demand in the decision to visit a specialist and in the number of such visits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

However, the data for the first wave were not used in the estimation except for the construction of instruments.

Some national health systems may have changed since the time span covered in our sample.

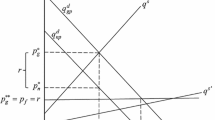

The models mentioned above can certainly describe the visits to some types of physicians. However, more complex models could describe better the demand for health services for other types of physicians. For example, in several countries the GPs act as gatekeepers of the medical system (see Table 1). This means that a visit to the GP is a compulsory step before visiting an SP. In this case, an alternative decision process with three stages could be proposed. The first stage which relates to the initial contact with a GP remains unaltered. At a second stage, the GP decides on a possible visit to an SP, and at a third stage the SP and the patient decide the duration of the treatment. However, the data that we use (ECHP) lack enough information to model this complex process.

Winkelmann [29] allows for correlation between the errors but finds that this correlation is not significantly different from zero.

We assume absence of zeros in the second stage. Given the nature of the data that we have, a zero inflated model [4, 5, 19] accounting for zeros in the second stage is not reasonable since we know that a patient decides to contact a physician only when she/he makes a visit. Therefore, the count for those who decide to visit a physician in the first stage is always at least 1.

See Winkelmann [28] for an exhaustive description of the different econometric specifications in each stage.

There is some controversy about the use of aggregate variables in studies with micro-units [17, 18]. One possibility suggested in the literature is to assume that variables common to sets of individuals are random (for instance, we can consider the country dummies as random in our specification). Any inference based on OLS (ordinary least squares) results could be misleading [3, 17]. By proceeding in this way, we normally get more precise estimates, but our results do not substantially change. Moreover, this assumption is valid when there is no correlation between the random effects and the regressors, which is a very hard assumption to maintain in panel data models.

It should be noted that although the inclusion of country dummies (fixed effects) could be problematic in the context of models with micro-units [18], the coefficients of variables with individual variation are roughly the same when including country dummies or country-specific time-varying variables.

Our results can be seen as being conditional on the size of the private sector in each country. However, when country dummies (which can be collecting the size of the private sector not varying in this short period of time) instead of time-varying country variables are included in the specification, the results for income do not change.

They are available from the authors on request.

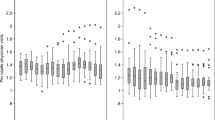

The reference male and female subjects are chosen to represent an average individual in the sample: married, head of a household of three members, employed, and with good health. The average visits to an SP have the following form: \( E(y_{i} |X_{i} ) = \frac{{1 - P(I_{i} = 0|X_{i} )}} {{P(y_{i} > 0|X_{i} )}}\lambda _{i} \), where \( \lambda _{i} = \exp (X_{i} \beta ) \) is the expected value of the negative binomial distribution that follows the visits to the SP. The average visits to a GP have the following form:\( E(y_{i} |X_{i} ) = {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^J {p_{j} \lambda _{j} } } \), where λ j is the expected number of visits (following a negative binomial distribution) of the class j of individuals and p j is the associated probability of belonging to class j.

References

Alvarez B (2001) La demanda atendida de consultas médicas y servicios urgentes. Investigaciones Económicas 25:93–138

Anderson K, Burkhauser R (1985) The retirement-health nexus: a new measure of an old puzzle. J Hum Res 20:315–330

Baltagi BH, Bresson G, Pirotte A (2003) Fixed effects, random effects or Hausman-Taylor? A pretest estimator. Econom Lett 79:361–369

Cameron AC, Trivedi PK (1986) Econometric models based on count data: comparisons and applications of some estimators and tests. J Appl Economet 1:29–53

Cameron AC, Trivedi PK (1998) Regression analysis of count data. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Cameron AC, Trivedi PK, Milne F, Piggot J (1988) A microeconometric model of the demand for health care and health insurance in Australia. Rev Econom Stud 55:85–106

Cromwell J, Michell J (1986) Physician-induced demand for surgery. J Health Econ 1:293–313

Deb P, Holmes AM (2000) Estimates of use and costs of behavioural health care: a comparison of standard and finite mixture models. Health Econ 9:475–489

Deb P, Trivedi PK (1997) Demand for medical care by the elderly in the United States: a finite mixture approach. J Appl Economet 12:313–336

Deb P, Trivedi PK (2002) The structure of demand for health care: latent class versus two-part models. J Health Econ 201:601–625

Grossman M (1972) The demand for health—a theoretical and empirical investigation. Columbia University Press, New York

Grytten J, Sørensen RR (2001) Type of contract and supplier-induced demand for supplementary dental insurance. J Health Econ 20:379–398

Heckman JJ, Singer B (1984) A method of minimizing the distributional impact in econometric models for duration data. Econometrica 52:271–320

Jiménez-Martín S, Labeaga JM, Martínez-Granado M (2000) An empirical analysis of the demand for health using the European Community Household Panel, WP 00/67. Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Madrid

Jiménez-Martín S, Labeaga JM, Martínez-Granado M (2002) Latent class versus two-part models in the demand for physician services across the European Union. Health Econ 11:301–321

Kenkel DS (1990) Consumer health information and the demand for medical care. Rev Econ Stat 22:587–595

Moulton BR (1986) Random group effects and the precision of regression estimates. J Economet 32:385–397

Moulton BR (1990) An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units. Rev Econ Stat 72:334–338

Mullahy J (1986) Specification and testing of some modified count data models. J Economet 33:341–365

Peracchi F (2000) The European Community Household Panel: a review. Empir Econ 27:63–90

Pohlmeier W, Ulrich V (1995) An econometric model of the two-part decision making in the demand for health care. J Hum Res 30:339–361

Propper C (2000) The demand for private health care in the UK. J Health Econ 19:855–876

Santos-Silva JMC, Windmeijer F (1997) Endogeneity in count data models: an application to demand for health care. J Appl Economet 12:281–294

Santos-Silva JMC, Windmeijer F (2001) Two-part multiple spell models for health care demand. J Econom 104:67–89

Sudman S, Bradburn N, Schwarz N (1996) Thinking about answers: the application of cognitive processes to survey methodology. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Vera-Hernández AM (1999) Duplicate coverage and demand for health care. The case of Catalonia. Health Econ 8:579–598

Wagstaff A (1986) The demand for health. Some new empirical evidence. J Health Econ 5:195–233

Winkelmann R (1998) Count data models with selectivity. Economet Rev 17:339–359

Winkelmann R (2001) Health care reform and the number of doctor visits—an econometric analysis. IZA discussion paper 317

Zweifel P (1981) Demande medical induite par l’offer: Chimere ou realite? Consomation 4:39–62

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Raquel Carrasco, Berthold Herrendorf, Andrew Jones, Owen O’Donnell and two anonymous referees for their many helpful comments. This study was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from The Merck Foundation, the philanthropic arm of Merck & Co. Inc. Whitehouse Station, New Jersey, USA and by BEC-2002-04294-C01-C02. All remaining errors are our own.

Interessenkonflikt:

Keine Angaben

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

The exact wording for the dependent variables is as follows:

-

For visits to medical doctors: “During the past 12 months, about how many times have you consulted a general practitioner (including home visits by the doctor)?”

-

For visits to specialists: “During the past 12 months, about how many times have you consulted a medical specialist (including out-patient consultations but excluding any consultation during hospitalisation)?”

The variables included in the analysis are grouped into the following three categories:

-

1.

Variables that affect the individual’s health perception

-

Age and its square

-

Household income and its square (in 105 PPP units), dated in wave −1

-

Variables measuring the individual’s health endowments as:

-A dummy if the individual reports himself/herself as having good health, dated in wave −1

-A dummy for individuals having a chronic physical or mental health problem, current (since it was not asked for in the first wave of the survey)

-A dummy if the individual is hampered in daily activities by any physical or mental health problem, illness or disability, dated in wave −1

-A dummy if the individual was admitted as in-patient in a hospital during the previous year, dated in wave −1

-

Variables measuring the time opportunity cost of the individual

-Relating to job status

a.Dummies for self-employment, unemployment, and retirement, dated in wave −1

b.Dummy for part-time employment, dated in wave −1

-Relating to the family structure

a.Marital status: two dummies, one taking value 1 if the individual is married, and the other equalling 1 if the individual is separated/divorced/widowed

b.A dummy for the individual being head of the household, dated in wave −1

c.Household size

-

-

2.

Variables that affect the probability of having a health shock and the knowledge of this likelihood

-

Education: a dummy for the individual having a third level of education

-

Occupational dummies for professionals, clerical workers, and services workers, dated in wave −1

-

Dummy for doing any type of supervisory job, dated in wave −1

-

Dummy for working in the public sector, dated in wave −1

-

Dummy that equals 1 if the individual perceives his/her job as risky, dated in wave −1

-

-

3.

Country-specific variables: see Table 1

In Table 4 we present summary statistics by sex and by sex and country.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jiménez-Martín, S., Labeaga, J.M. & Martínez-Granado, M. An empirical analysis of the demand for physician services across the European Union. HEPAC 5, 150–165 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-003-0215-0

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-003-0215-0