Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence and risk factors for anxiety and depression symptoms in outpatient migraineurs in mainland China. In addition, we evaluated whether the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) provided sufficient validity to screen depression and anxiety. A cross-sectional study was conducted consecutively at our headache clinic. Migraine was diagnosed according to International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition (ICHD-II). Demographic characteristics and clinical features were collected by headache questionnaire. Anxiety and depression symptoms about migraineurs were assessed using HADS. Several questionnaires were simultaneously used to evaluate patients with depressive disorder including the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 (HAMD), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAMA) and HADS. Pearson correlation analysis was applied to test the validity of HADS. 176 outpatients with migraine (81.8 % female) were included. Overall, 17.6 and 38.1 % participants had depression and anxiety, respectively. Possible risk factors for depression in migraineurs included headache intensity of first onset of migraine, migraine with presymptom, migraine with family history and migraine disability. The possible risk factors for anxiety included fixed attack time of headache in one day and poor sleeping, and age represented a protective factor for anxiety. The correlation coefficient of HADS-A and HADS-D with HAMA and HAMD was 0.666 and 0.508, respectively (P < 0.01). This study demonstrates that depression and anxiety comorbidity in our mainland Chinese migraineurs are also common, and several risk factors were identified that may provide predictive value. These findings can help clinicians to identify and treat anxiety and depression in order to improve migraine management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Migraine and depression are highly prevalent, and both represent disabling diseases in populations. Studies have found that the prevalence of migraine was 17.1 % in females and 5.6 % in males [1]. In addition, epidemiological studies found an association between migraine and depression [2–5], indicating that the lifetime prevalence of depression in migraine ranged from 18.8 to 42 % [2, 3, 6]. Interestingly, migraineurs were 2.2–4.0 times more likely to suffer depression than non-migraineurs [7], and there was an increasing suicidal tendency and attempts in migraine with comorbid depression [8]. Breslau concluded that association between migraine and major depression may result from bi-directional influences; each disorder would increase the risk for first onset of the other [9].

Previous studies have also found that anxiety, particularly general anxiety disorder, was common in migraineurs [4]. Furthermore, a study using Chinese subjects from Taiwan found that migraine were associated with both depression and anxiety [10] and the onset of anxiety typically preceding the onset of migraine with the risk of depression increasing subsequently [11]. However, due to economic and cultural differences, the pattern in mainland China may be different than that in Western countries or Taiwan.

Several studies supported that psychiatric comorbidities could promote the episodic headaches transform into chronic syndromes [12, 13]. This transformation may increase the difficulty in both treatment and headache-related disability [2]. Therefore, these findings indicate that psychiatric comorbidity must be treated in timely manner; however, the identification and diagnosis of psychiatric comorbidity in migraineurs is much lower, especially in China. Understanding the risk factors associated with depression and anxiety in migraineurs will provide helpful information for clinicians to prevent and treat these disorders. To date, only a few studies have examined the demographics and clinical features in patients with headaches associated with depression [14, 15], and no studies have investigated the risk factors for depression and anxiety in migraineurs.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a fast screening tool, to screen depression and anxiety symptoms in somatic, psychiatric and primary care patients [16].

Therefore, the purpose of our study was to assess the prevalence and risk factors for anxiety and depression in migraine outpatients in mainland China. In addition, we also tested the validity of the HADS to determine whether this tool displays sufficient validity to screen depression and anxiety symptoms in migraineurs.

Methods

Subjects and procedures

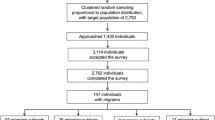

One hundred and eighty-five consecutive migraine patients were included in this study. These patients visited the headache outpatient clinic in the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University in China from September 2009 to January 2011. Migraine diagnosis was conducted by a neurologist according to the ICHD-II [17], and the diagnosis was confirmed by a headache specialist. The following criteria were also utilized. The course of migraine must be more than 1 year. Subjects were excluded if they had experienced significant life-changing events (e.g. seeing others being killed, death and serious injury; hearing some terrible things; being raped; being divorced, etc.) recently [18], or were prescribed antidepressants or other psychotropic drugs in the past 2 weeks. According to these criteria, nine patients were excluded from the study, and 176 people included in the final study. 94.3 % of the subjects were of Chinese Han ethnicity.

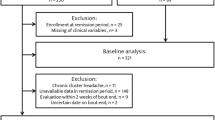

To test the validity of the HADS, 30 consecutive major depression disorder patients (66.7 % female) were included who visited the psychiatry department in the same hospital from January 2011 to May 2011. The age of the subjects ranged from 20 to 59 years (average 36.5 ± 10.9 years). Depression was diagnosed by a psychiatry specialist according to the Structured Clinical Interview provided in the DSM-IV-text revision (TR) Axis I Disorders [18]. The patients were also assessed by a psychiatrist. 98 % of the subjects were of Chinese Han ethnicity.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee at Chongqing Medical University and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients had given written consent to the study.

All headache information was collected by three neurologists through face-to-face interviews. The findings were then reviewed by a headache specialist, and anxiety and depression symptoms of the migraineurs were assessed by a psychiatrist. Demographic characteristics and clinical features were collected using a headache questionnaire. Demographic characteristics included age, sex, employment status, educational level (four categories: ≤6, 7–9, 10–12, >12 years), dwelling (three categories: living in town, in suburban area, in countryside) etc.; and clinical features of the migraine headache included the first onset age, headache pain intensity, headache nature, locus, duration, presymptom (e.g., fluctuating mood, drowsiness, reduced activity, yawning, desire to eat, neck tightness, etc.), the average monthly headache frequency in the recent 3 months, family migraine history (first-degree relatives), migraine disability, sleeping (i.e., excellent, better, bad, worst), etc. Finally, a question about life events (Were there any events which were difficult to handle that influenced your mood in the last month?) was included as well as the psychiatry medication history in the past 2 weeks.

Measures

Headache pain intensity was assessed by an 11-point pain scale (0–10) with 0 indicating “no headache” and 10 indicating “headache as severe as I can imagine” [19]. 1–3 was defined as “mild”; 4–6 as “moderate”; and 7–10 as “severe”. Migraine-related disability was assessed by The Migraine Disability Assessment questionnaire (MIDAS) [20]. Participants were divided into four grades by MIDAS using previously validated scores based on lost-time due to headaches (i.e., minimal, mild, moderate, and severe disability). In addition, ICHD-II was also applied to divide the patients into subgroups, and the subgroups included migraine with aura (MA) and migraine without aura (MOA) or episodic migraine (EM) and chronic migraine (CM) [17].

Anxiety and depression were assessed utilizing HADS [16]. It is a well-established self-rating instrument with 14 items, and incorporates seven anxiety questions (HADS-A) and seven depression questions (HADS-D). Each item is scored from 0 (not present) to 3 (maximally present), representing a 4-point scale. Because the total score of each subscale is 21, the total score of each subscale that is greater than eight indicates that the person may have anxiety (ANX) or depression (DEP) symptoms. If the total score of HADS-D ≥8 and HADS-A <8, the person has pure depressive symptoms (pure DEP). If the total score of HADS-A ≥8 and HADS-D <8, the person has pure anxiety symptoms (pure ANX). When the total score of both HADS-A and HADS-D ≥8, it accounts for that the person has comorbid symptoms (COM). Previous studies indicated that the correlation of HADS-D and HADS-A with other commonly used anxiety and depression questionnaires such as Beck Depression Inventory(BDI), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), and SCL-90 Anxiety and Depression subscales, respectively, were between 0.60 and 0.80, the validity and reliability of HADS are good [21, 22].

In order to check the validity of HADS in Chinese subjects, we simultaneously evaluated major depression disorder patients using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 (HAMD-17), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAMA), and HADS. Previous studies have found that HAMD and HAMA also have good valid and reliability [23–25].

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using the SPSS 17.0 statistics package. Continuous variables data were expressed as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA and χ2 tests were used for comparison when appropriate. We used binary logistic regression to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) for pure DEP, pure ANX and COM in persons having EM and CM, and also analyzed both genders. We evaluated potential confounding by adjusting for age and education, and investigated potential interaction effects between gender and pure DEP, pure ANX and COM by including the product of the two variables in the logistic regression analyses. We used the Wald χ2 statistic to test the interaction coefficients.

When analyzing the risk factors for depression or anxiety in migraineurs, we used binary logistic regression with a backward progression. The dependent variable was the presence or absence of depression or anxiety symptoms. The 18 independent variables consisted of the following: age (three categories: <30, 30–45, >45 years), gender, educational years, profession, dwelling, the first-onset age of migraine (<20, 20–35, >35 years), headache pain intensity of first onset of migraine (none, mild, moderate, severe), average monthly headache frequency in the recent 3 months (≤8, 9–14, ≥15 days per month), frequency of headache in 1 year (<1, 2–3, 4–6, >6 months), the most painful degree (none, mild, moderate, severe), fixed attack time in one day (yes/no), fixed attack time on year (yes/no), presymptom, course of disease (≤15, 16–30, >30 years), sleeping, family history of migraine (yes/no), migraine disability (minimal, mild, moderate, severe), and headache pain intensity of migraine now (none, mild, moderate, severe).

When checking the validity of the HADS, the normality of data was first tested for HAMD, HAMA, and HADS, and the results indicated that all demonstrated normal distributions. We then used the Pearson product-moment correlation analysis to analyze the correlation of HADS-A and HADS-D with HAMA and HAMD.

A significance level of P < 0.05 was chosen in all statistical hypotheses, and all statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

Migraine characteristics

The migraine samples including 144 (81.8 %) females and 32 (18.2 %) males, ranging in age from 14 to 63 years (average 39.1 ± 11.6 years). The average first-onset age of migraine was 23.8 ± 10.3 years. The average course of migraine was 15.4 ± 11.0 years. The headache frequency during the last 3 months were 106 patients (60.2 %) with ≤8 days/month, 17 (9.7 %) with 9–14 days/month, and 53 patients (30.1 %) with ≥15 days/month. A significant difference was observed for depression and anxiety in different frequency of headache (DEP: F = 3.11, P = 0.047; ANX: F = 3.48, P = 0.033). Our results indicated that the seriousness of depression and anxiety symptoms were correlated with the frequency of the headache. The average intensity score of the headache in a recent month was 7.4 ± 1.3. The migraine subtypes are shown in Table 1.

Depression symptoms and anxiety symptoms in migraineurs

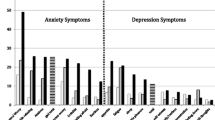

The average depression score of migraineurs was 4.4 ± 3.6, and depression symptoms (DEP) occurred in 17.6 % (31 of 176). The prevalence rate of depression symptoms in females was twice than that in males (19.4 vs. 9.4 %), but no significant difference was found between sex (P > 0.05). The prevalence rate of depression symptoms in MOA was 17.1 % (26 of 152), in MA was 20.8 % (5 of 24); and 13.8 % (17 of 123) in EM, 26.4 % (14 of 53) in CM. A significant difference of prevalence rate was detected in depression symptoms between EM and CM (χ2 = 4.05, P = 0.044).

The average anxiety score of migraineurs was 6.5 ± 3.8. Anxiety symptoms (ANX) occurred in 38.1 % (67 of 176). The prevalence rate of anxiety symptoms in females was higher than in males (41.9 vs. 25.0 %), but no significant difference was observed between sex (P > 0.05). The prevalence rate of anxiety symptoms in MOA was 37.5 % (57 of 152), in MA was 41.7 % (10 of 24); and 33.3 % (41 of 123) in EM, 49.1 % (26 of 53) in CM, there was significant difference between EM and CM (χ2 = 3.88, P = 0.049).

In all migraine patients there were only 2.8 % comorbid pure DEP, 23.3 % comorbid pure ANX, and 14.8 % comorbid both DEP and ANX. Depression and anxiety symptoms were more common in females (Table 1).The odds ratio of pure DEP, pure ANX and COM prevalence in persons with CM compared to EM are shown in Table 2. COM was more likely to occur in CM, especially in females having CM rather than in those with EM. No significant associations were found between pure DEP and pure ANX in either the CM or EM groups.

Risk factors for depression in migraineurs

Logistic regression analysis revealed that the following four factors were associated with depression in migraineurs: (1) headache intensity of first onset of migraine, (2) presymptom of migraine (mainly including: fluctuating mood, drowsiness, reduced activity, yawning), (3) migraine family history, and (4) migraine disability. We found the moderate headache intensity was the highest risk factor for depression as compared to mild and severe headache intensity in first onset of migraine. Presymptom and family migraine history were also risk factors for depression; and the mild, moderate and severe disability were all significantly different than minimal disability on the outcome measure for depression (Table 3).

Risk factors for anxiety in migraineurs

Logistic regression analysis revealed that age was a protective factor for anxiety. For example, a lower incidence of anxiety was correlated with the increasing age of the patient. However, fixed attack time of headache in one day and poor sleeping were the risk factors associated with anxiety in migraineurs (Table 4).

Validity of HADS

Correlation analysis was used to analyze the results of HAMD, HAMA and HADS from the patients of major depression disorder, and the results of the correlation coefficient of HADS-A with HAMA was 0.666 and HADS-D with HAMD was 0.508 (Table 5). Of these 30 major depressive disorder patients 27 patients had the total score of HADS-D ≥8, so the sensitivity of HADS-D was 90 % (27/30); and there were 26 patients with a total score of HADS-A ≥8, so the sensitivity of HADS-A was 86.7 % (26/30).

Discussion

Incidence of depression and anxiety symptoms

In our headache outpatient clinic, we used HADS to detect depression and anxiety symptoms in migraine patients. The results found that the incidence of depression symptoms was 17.6 %. This finding was lower than the rates observed in other clinical studies, including 20 % seen in UK [26] and 23.1 % seen in Italy [27], and are also lower than the rate in a population-based study which ranged from 28.5 to 42 % in USA [4, 5]. Wang [10] investigated the prevalence of depression in the elderly headache patients in Taiwan, and found that the prevalence of depression was 13.4 %; however, headache subtypes were not examined. The incidence of anxiety symptoms was 38.1 % in our samples, which was similar to the results of a study from Italy (38.1 %) [27], but lower than a population-based study (51 %) from the USA [28].

These differences may result from inherent differences associated with race and culture [29] or different evaluation instruments. Chinese culture tends to express depression somatically (e.g., fatigue, sleep problems, headache, muscle pain, etc.), but tends to deny psychological symptoms, especially depression. Therefore, depression has lower rate of detection and diagnosis, and is easily misdiagnosed as neurasthenia [30, 31]. In our study, when we informed patients that we would assess their depression and anxiety status, some patients felt irritated and denied that they had a psychiatric disorder, and they tried to refuse the assessment. However, when investigators explained that it was just a mood assessment and told them that the correct assessment could help to treat their headache, the patients agreed to comply. When they were completing the questionnaire, they seemed to avoid of expressing their real depressive mood.

The seven depression items of HADS mainly assess the mood symptoms including lowered mood, anhedonia, and psychomotor retardation; however, HADS lacks assessment items regarding somatic symptoms. In previous studies, DSM-IV, HAMD, HAMA, or Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) were used to evaluate mood, which contain items about somatic symptoms [2, 3]. Therefore, the use of HADS in our study to a certain extent may have led to our lower detection rate of depression.

The validity of HADS

Previous studies indicated that HADS is a valid and reliable instrument to screen for depression and anxiety symptoms [21]. Furthermore, Juang [22] found that HADS was a valid and reliable in a study of headache patients in Taiwan. Because this test requires less time to complete, we used HADS to evaluated depression and anxiety symptoms in migraineurs. As our rate of depression or anxiety symptoms was lower than previous studies, we questioned whether HADS represented a valid measure. Therefore, we compared the findings from HADS to that of HAMD and HAMA in patients with major depression disorder. The correlation coefficient of HADS-A and HADS-D with HAMA and HAMD were 0.666 and 0.508, respectively, similar to previous study [21]. But the correlation of HADS-D with HAMD was somewhat lower, although the sensitivity of HADS-D was good; this might be the cause that led to lower detection results in our study. Therefore, our findings suggest that future studies could utilize BDI and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) or HAMD and HAMA to evaluate depression or anxiety symptoms in migraineurs. These scales represent professional assessment scales that have a better validity and reliability [24, 25, 32].

The relationship of the DEP and ANX with migraine characteristics and subgroups

Our study demonstrates that migraine was associated with depression and anxiety, and the prevalence was higher in females than males, which is consistent with the previous studies [2, 3]. Moreover, the prevalence of depression and anxiety in the general population was also higher in females than in males [33]. We observed that frequency of headaches was associated with more serious depression and anxiety symptoms in agreement with Mitsikostas’ results [34]. We also found a stronger relationship of COM with CM than with EM. These results indicate that doctors should check whether the patient has comorbid depression or anxiety symptoms if headaches occur frequently in a migraineur, especially to be vigilant in managing the COM in CM.

Risk factors for DEP and ANX in patients with migraine

Fewer studies explored the risk factors for mental disorder in migraineurs. In this study, we found that only moderate headache among the first onset of migraine was associated with depression. This result was contrary to those of Mitsikostas’ study [34] where the frequency and the duration of the headache attacks were significantly associated with depression or anxiety, not the intensity of headache. However, he did not divide the headache into subtypes, and the degree of headache with first onset of migraine may be confounded by recall bias in our study, potentially leading to this discrepancy.

We also found that headache-related disability was a risk factor for depression consistent with Jelinski’s study [14], who observed that severe headache-related disability was independently associated with depression. However, he did not divide the headache into subtypes either. In addition, we discovered another two risk factors for depression including the family migraine history (first-degree relatives) and presymptoms of migraine (i.e., fluctuating mood, drowsiness, reduced activity, yawning). Merikangas [35] found a significant association between migraine and depression in both probands as well as the relatives. In our study, we observed that patients were more likely to suffer from depression if the patients had a family history of migraines.

We also found that the perception of presymptoms of migraine enabled patients to forecast headache attacks in advance, a finding that has not yet been reported in previous studies. This perception may induce a patient’s fear of headache and depression symptoms. In this finding also exists a confounding factor, fluctuating mood, which is one of the presymptoms of migraine that might be assessed in the outcome measure and hence be a possible confounder. Even so, clinicians should note depression symptoms if migraine patients present presymptoms for a better and timely treatment.

We only found two factors that were independent risk factors for anxiety including a fixed attack time of headache in one day and poor sleeping. Frisoni’s study [36] indicated that anxiety was independently associated with quality of sleep. In addition, Morrison [37] investigated sleep problems in 943 adolescents from the general population, and found that adolescents reporting sleep problems were more anxious and depressed. To date, no studies have identified a relationship between fixed attack time and mood disorders, which is potentially related to the fluctuations of ovarian hormones [38]. Interestingly, we observed that age was a protective factor for anxiety. Only one investigation reported a decrease of depression disorder prevalence in older age groups [2].

The necessity of treatment for mental disorder

Migraine and depression significantly decrease the quality of life [2] and lead to a worse prognosis, chronic disease, and a decreased response to treatment [39]. Pesa [40] indicated that migraine comorbid with depression or anxiety also results in significantly higher medical costs as compared to migraine alone. Therefore, early diagnosis and treatment for psychiatric comorbidity are very important. If comorbid depression is not recognized and treated effectively, successful headache management is unlikely. Furthermore, it is obviously not appropriate for doctors to exclusively focus on the treatment of headache symptoms of migraine patients and neglect the psychiatric comorbidity under the traditional medical model. When treating migraine headaches, clinicians should be alert to psychiatric comorbidity, and then treat psychiatric comorbidity in a timely manner in order to prevent the functional lesion of migraineurs. This strategy would certainly be beneficial to the improvement of their life quality.

Limitations

Our study has some methodological limitations. First, migraine patients in our study were limited to those who did not have great life events recently and those who had not taken antidepressants or other psychotropic drugs in the past 2 weeks. The purpose of these exclusion criteria was to prevent confounders that may affect the mood characteristics. Second, the sample size was not large enough to detect a difference between MA and MOA. Third, we checked the validity of HADS only in major depression disorder patients in our psychiatric department, but not in migraine patients. We believed that the results would be more accurate if the validity of the HADS was evaluated among patients that were exactly diagnosed with major depression disorder.

This study has several clinical implications. First, the comorbidity of depression and anxiety in mainland Chinese migraineurs is common. When clinicians treat headache of migraine, they should pay close attention to psychiatric comorbidity, and treat these disorders in a timely manner. Second, as our results suggest, multiple risk factors are associated with depression and anxiety in migraineurs. Thus, when migraineurs come to seek help from clinician, clinicians should pay attention to these factors because these risk factors can be helpful for predicting and identifying mood symptoms.

Abbreviations

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- ICHD-II:

-

International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition

- MIDAS:

-

The migraine disability assessment questionnaire

- MA:

-

Migraine with aura

- MOA:

-

Migraine without aura

- EM:

-

Episodic migraine

- CM:

-

Chronic migraine

- ANX:

-

Anxiety symptoms

- DEP:

-

Depression symptoms

- HADS-A:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (anxiety subscale)

- HADS-D:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (depression subscale)

- HAMD:

-

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

- HAMA:

-

Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale

References

Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, Stewart WF (2007) Migraine: prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology 68:343–349. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21, 17261680, 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD2s%2FlslCgsg%3D%3D

Jette N, Patten S, Williams J, Becker M, Wiebe S (2008) Comorbidity of migraine and psychiatric disorders—a national population-based study. Headache 48:501–516. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00993.x, 18070059, 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00993.x

Molgat CV, Patten SB (2005) Comorbidity of major depression and migraine—A Canadian population-based study. Can J Psychiatry 50:832–837, 16483117

Antonaci F, Nappi G, Galli F, Manzoni GC, Calabresi P, Costa A (2011) Migraine and psychiatric comorbidity: a review of clinical findings. J Headache Pain 12(2):115–125. doi:10.1007/s10194-010-0282-4, 21210177, 10.1007/s10194-010-0282-4

Breslau N, Andreski P (1995) Migraine, personality and psychiatric comorbidity. Headache 35:382–386. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1995.hed3507382.x, 7672954, 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1995.hed3507382.x, 1:STN:280:DyaK2MvgtlWhsQ%3D%3D

Tietjen GE, Peterlin BL, Brandes JL, Hafeez F, Hutchinson S, Martin VT et al (2007) Depression and anxiety: effect on the migraine–obesity relationship. Headache 47:866–875. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00810.x, 17578537, 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00810.x

Hamelsky SW, Lipton RB (2006) Psychiatric comorbidity of migraine. Headache 46:1327–1333. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00576.x, 17040330, 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00576.x

Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P (1991) Migraine, psychiatric disorders, and suicide attempts: an epidemiologic study of young adults. Psychiatry Res 37(1):11–23. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(91)90102-U, 1862159, 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90102-U, 1:STN:280:DyaK3MzhvFynsg%3D%3D

Breslau N, Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Schultz LR, Welch KMA (2003) Comorbidity of migraine and depression. Neurology 60(8):1308–1312. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000058907, 12707434, 10.1212/01.WNL.0000058907.41080.54, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3s7ovVKhsQ%3D%3D

Wang SJ, Liu HC, Fuh JL, Liu CY, Wang PN, Lu SR (1999) Comorbidity of headaches and depression in the elderly. Pain 82:239–243. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00057-3, 10488674, 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00057-3, 1:STN:280:DyaK1Mvhs1OktQ%3D%3D

Mercante JPP, Peres MFP, Bernik MA, Corchs F, Guendler VZ, Zukerman E (2011) Disease progression to chronic migraine: onset of symptoms of headaches, anxiety and mood disorders. Headache Med 2(1):5–9

Lipton RB, Pan J (2004) Is migraine a progressive brain disease? JAMA 291:493–494. doi:10.1001/jama.291.4.493, 14747508, 10.1001/jama.291.4.493, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXos12mtA%3D%3D

Scher AI, Lipton RB, Stewart W (2002) Risk factors for chronic daily headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep 6:486–491. doi:10.1007/s11916-002-0068-8, 12413408, 10.1007/s11916-002-0068-8

Jelinski SE, Magnusson JE, Becker WJ, CHORD Study Group (2007) Factors associated with depression in patients referred to headache specialists. Neurology 68:489–895. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000253183.57001.b3, 17296914, 10.1212/01.wnl.0000253183.57001.b3

Chung MK, Kraybill DE (1990) Headache: a marker of depression. J Fam Pract 31:360–364, 2212965, 1:STN:280:DyaK3M%2FhtFarug%3D%3D

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67:361–370. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x, 6880820, 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x, 1:STN:280:DyaL3s3nvFWjug%3D%3D

The international classification of headache disorders: 2nd edition (2004). Cephalalgia 24 Suppl 1:9–160

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (2002) Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P). Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York

Kwong WJ, Pathak DS (2007) Validation of the eleven-point pain scale in the measurement of migraine headache pain. Cephalalgia 27:336–342. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01283.x, 17376110, 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01283.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD2s7ns1ensg%3D%3D

Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, Sawyer J (2001) Development and testing of the migraine disability assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology 56(suppl 1):S20–S28, 11294956, 10.1212/WNL.56.suppl_1.S20, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3M3ivVGntA%3D%3D

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelman D (2002) The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 52(2):69–77. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3, 11832252, 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3

Juang KD, Wang SJ, Lin CH, Fuh JL (1999) Use of the hospital anxiety and depression scale as a screening tool for patients with headache. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei) 62:749–755, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3c%2FktlSmtA%3D%3D

Hamilton M (1967) Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 6(4):278–296, 6080235, 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x, 1:STN:280:DyaF1c7isFSnuw%3D%3D

Miller IW, Bishop S, Norman WH, Maddever H (1985) The Modified Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: reliability and validity. Psychiatry Res 4:131–142. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(85)90057-5, 10.1016/0165-1781(85)90057-5

Maier W, Buller R, Philipp M, Heuser I (1988) The Hamilton Anxiety Scale: reliability, validity and sensitivity to change in anxiety and depressive disorders. J Affect Disord 14:61–68. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(88)90072-9, 2963053, 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90072-9, 1:STN:280:DyaL1c7hs1aquw%3D%3D

Devlen J (1994) Anxiety and depression in migraine. J ROY SOC MED 87(6):338–341, 8046705, 1:STN:280:DyaK2czit1egtQ%3D%3D

Beghi E, Bussone G, Amico DD, Cortelli P, Cevoli S, Manzoni GC et al (2010) Headache, anxiety and depressive disorders: the HADAS study. J Headache Pain 11:141–150. doi:10.1007/s10194-010-0187-2, 20108021, 10.1007/s10194-010-0187-2

Breslau N (1998) Psychiatry comorbidity in migraine. Cephalalgia 18(Suppl 22):S56–S61

Ryder AG, Yang J, Heine SJ (2002) Somatization versus psychologization of emotional distress: A paradigmatic example for cultural psychopathology. In: Lonner WJ, Dinnel DL, Hayes SA, Sattler DN (eds), Online readings in psychology and culture (9th ed). Bellingham

Lin TY (1989) Neurasthenia revisited: its place in modern psychiatry. Cult Med Psychiatry 13:105–129. doi:10.1007/BF02220656, 2766788, 10.1007/BF02220656, 1:STN:280:DyaL1MzlsF2qtg%3D%3D

Chan B, Parker G (2004) Some recommendations to assess depression in Chinese people in Australasia. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 38:141–147. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1614.2004.01321.x, 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01321.x

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J (1961) An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 4:561–571, 13688369, 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004, 1:STN:280:DyaF3c%2FgslKisg%3D%3D

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR et al (2003) The epidemiology of major depressive disorder. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R). JAMA 289:3095–3105, 12813115, 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095

Mitsikostas DD, Thomas AM (1999) Comorbidity of headache and depressive disorders. Cephalalgia 19:211–217. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1999.019004211.x, 10376165, 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1999.019004211.x, 1:STN:280:DyaK1MzgsVCmsQ%3D%3D

Merikangas KR, Risch NJ, Merikangas JR, Weissman MM, Kidd KK (1988) Migraine and depression: association and familial transmission. J Psychiatr Res 22:119–129. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(88)90076-3, 3404480, 10.1016/0022-3956(88)90076-3, 1:STN:280:DyaL1czgtVKruw%3D%3D

Frisoni GB, Leo Dd, Rozzini R, Bernardini M, Buono MD, Trabucchi M (1992) Psychic correlates of sleep symptoms in the elderly. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry 7:891–898. doi:10.1002/gps930071208, 10.1002/gps.930071208

Morrison DN, McGee R, Stanton WR (1992) Sleep problems in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31:94–99. doi:10.1097/00004583-199201000-00014, 1537787, 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00014, 1:STN:280:DyaK387msFOitg%3D%3D

Baskin SM, Smitherman TA (2009) Migraine and psychiatric disorders: comorbidities, mechanisms, and clinical applications. Neurol Sci 30(Suppl 1):S61–S65. doi:10.1007/s10072-009-0071-5, 19415428, 10.1007/s10072-009-0071-5

Pompili M, Cosimo DD, Innamorati M, Lester D, Tatarelli R, Martelletti P (2009) Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with chronic daily headache and migraine: a selective overview including personality traits and suicide risk. J Headache Pain 10(4):283–290. doi:10.1007/s10194-009-0134-2, 19554418, 10.1007/s10194-009-0134-2

Pesa J, Lage MJ (2004) The medical costs of migraine and comorbid anxiety and depression. Headache 44:562–570. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.446004.x, 15186300, 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.446004.x

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support of the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 30970988) and Medical Scientific Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Health Bureau (Grant Nos. 2009-2-31 and 2010-2-087). Funding was from Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 30970988) and Medical Scientific research Program of Chongqing Municipal Health Bureau (Grant Nos. 2009-2-31 and 2010-2-087).

Conflict of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yong, N., Hu, H., Fan, X. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for depression and anxiety among outpatient migraineurs in mainland China. J Headache Pain 13, 303–310 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-012-0442-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-012-0442-9