Abstract

We report a case of a woman presenting, 7 days after epidural analgesia for a caesarean section, to the emergency room for a worsening of the headache and tonico-clonic seizures. MRI showed alterations suggestive of the presence of intracranial hypotension (IH) as well as evidence of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). She was treated with a blood patch which leads to the prompt regression of the clinical symptoms and follow-up MRI, after 15 days, showed complete resolution of radiological alterations. The possible pathogenetic relationship between IH, secondary to the inadvertent dural puncture, and PRES is discussed. We suggest that venous stagnation and hydrostatic edema, secondary to intracranial hypotension, probably played a crucial role in the pathogenesis of PRES.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is a clinical and neuroradiological entity, characterized by a disorder of cerebrovascular autoregulation, whose neuroradiological and clinical alterations are commonly completely reversible.

We present and debate a case of a woman with clinical and radiological sings of intracranial hypotension (IH) which probably evolved towards PRES.

Case report

A healthy 41-year-old woman went to the delivery suite at 42 weeks. She underwent epidural analgesia for a caesarean section with no apparent complications with the exception of a mild headache. Immediately after the labour she received mezlocillin, ketorolac, ranitidine, metoclopramide, fluids and heparin.

Seven days later, she came to the emergency room because of worsening of the headache and appearance of tonico-clonic seizures. The headache had a gradual onset, was bilateral, pressure-like, with a postural component. Neurologic assessment revealed mild left motor syndrome, mild right anisocoria and rapid deterioration of the mental status; EEG was negative. Blood pressure, routine blood work and urinalysis were normal and there were no signs of peripheral edema. She was intubated, underwent sedation and life support, and was transferred to intensive care unit. Then she received antibiotics, corticosteroid and parental nutrition was started.

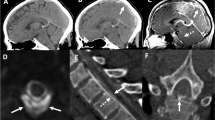

The first brain MRI (Fig. 1) revealed the presence of multiple symmetric and bilateral, subcortical–cortical patchy areas, hyperintense in T2-weighted images, in the vertebrobasilar vascular territory, in the frontal lobes and in the watershed areas among ACA-ACM vascular territories, which showed high signal on DWI as well as on ADC maps, indicating the presence of vasogenic edema.

First MRI at the admission. a Patchy areas hyperintense in T2-weighted images involving bilaterally white matter of the occipital lobes and watershed areas between ACA-ACM vascular territories (arrows) which show b high signal on ADC maps (arrows). c Decreased angle between straight sinus and vein of Galen (black arrow) and downward displacement of the brain (white arrow), “sagging” midbrain and enlargement of venous structures (curved arrow) and of pituitary gland. d No evidence of venous thrombosis on venous angiography. f No areas of constriction and dilatation on 3D TOF MRA MIP images of the Circle of Willis. e T1 post-contrast images show enhancing pachimeningeal thickening (arrows)

MRI also revealed the presence of pachimeningeal thickening, enhancing after contrast administration, downward displacement of brain and engorgement of venous structures, such as dural sinuses, Galen vein and epidural venous plexi, with no evidence of venous thrombosis on venous angiography. The circle of Willis MRA was normal.

The patient was treated with support therapy followed by blood patch on the basis of the hypothesis that the IH was related to a CSF leak due to an inadvertent dural puncture.

Fifteen days after admission, all the symptoms resolved and the follow-up MRI (Fig. 2) demonstrated near complete disappearance of the hyperintense areas, pachimeningeal thickening and venous engorgement.

Control MRI 15 days after admission and dural patch. a Almost completed resolution of the alterations on T2-FLAIR images. b Disappearance of the high signal areas on ADC images. c Post-contrast T1-weighted images show disappearance of pachimeningeal thickening and enhancement after contrast administration. d Reduction of venous enlargement and decrease of downward displacement of midbrain, increase of angle between vein of Galen and straight sinus

Discussion

Intracranial hypotension (IH) is a syndrome, clinically characterized by postural headaches elicited or exacerbated by upright position, caused by reduction of CSF volume under normal limits [1].

This syndrome could be primary (idiopathic) or secondary to a variety of causes and could be the result of inadvertent dural puncture during epidural analgesia (0.26–2%) [2].

Generally, IH syndrome is self-limiting and has symptoms subsiding after 2–16 weeks. Conservative therapy is usually sufficient; nevertheless, in the suspect of a meningeal leak or after a lumbar puncture, epidural blood patch or saline infusion can provide almost immediate relief [3, 4].

PRES is characterized by symmetric bilateral subcortical–cortical hyperintensities in T2-weighted images, more often in parieto-occipital lobes. The preferential involvement of posterior brain regions is probably due to regional heterogeneity of the arterial sympathetic innervation which is maximal in the anterior circulation and decreases with an anterior-to-posterior gradient; therefore, the occipital lobes and the other posterior brain regions are at relative highest risk for hydrostatic edema [5].

The radiological alterations are associated with clinical symptoms including headache, vomiting, nausea, abnormalities of visual perception, altered alertness and behaviour, mental status abnormalities, seizure and occasionally focal neurological signs [6].

Clinical and neuroradiological alterations are usually reversible, although an ischemic evolution is possible; thus, a prompt treatment is necessary to prevent irreversible brain damage [7].

In our patient, the first brain MRI revealed the presence of pachimeningeal thickening, enhancing after contrast administration, downward displacement of brain and engorgement of venous structures, typical signs of IH, and no evidence of venous thrombosis at MR angiography. These features were associated with symmetric and bilateral multiple subcortical–cortical patchy areas, hyperintense in T2-weighted images, which showed a high signal on ADC maps, localized in the vertebrobasilar vascular territory, in frontal lobes and in watershed areas between ACA-ACM vascular territories, signs which are suggestive of PRES.

The possible differential diagnoses included reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) associated with postpartum angiopathy and eclampsia, but RCVS was ruled out mainly because of the subacute and progressive onset of the clinical symptoms, which were prevalently and predominantly postural headache associated with seizures, rather than thunderclap headache. Furthermore, a negative eclampsia panel ruled out eclampsia, as well as there was no evidence of arterial hypertension, proteinuria, liver function abnormalities or peripheral edema on examination and none of the drugs used in the peri-partum period had a vasoactive effect which could have been responsible for RCVS. Moreover, the circle of Willis was normal on MRA, whereas RCVS is characterized by a reversible segmental and multifocal vasoconstriction of cerebral arteries involving large- and medium-sized arteries in the anterior and posterior circulations, with occasional dilated segments [8].

In our patient, IH was probably induced by inadvertent dural puncture during the epidural anaesthesia. The main symptom of IH was the mild postural headache. Our hypothesis is that this condition could have played a crucial role for the development of PRES which was clinically characterized by the onset of seizures and rapid deteriorating conscience status. Although not reported in literature, a physiopathological relationship between IH and PRES could be arguable.

Two different but related mechanisms involved in IH could have lead to PRES.

First one was the venous stagnation due to venous engorgement explained by the Monroe–Kelly doctrine which states that: “with an intact skull, the sum of the volume of the brain plus CSF volume plus blood volume is constant. Therefore, an increase in one of them should cause a reduction in one or in both of the remaining two” [9].

The second one was the impaired drainage of deep venous system due to a functional stenosis of vein of Galen entering the straight sinus produced by brain sagging [10].

All these modifications increased venous pressure with passive overdistension of venous system and of the cerebral arterioles, leading to interstitial extravasation of proteins and fluids mainly in vertebrobasilar vascular territory, which resulted in the typical MRI signs of PRES.

It has been demonstrated by Savoiardo et al. that venous stagnation could result in swelling of deep brain structures with a statistically significant increase of the ADC values. High ADC values have been reported in parietal lobes as well. It could therefore be possible that in more severe cases, cerebral edema could lead to PRES.

In our patient this hypothesis is supported by the chronological evolution of symptoms related to the different syndromes and by the resolution of neurological symptoms and radiological alterations of both IH and PRES only after a blood patch, used for the treatment of IH, without any other specific therapy used to treat PRES. Moreover, there were no other apparent specific causes of PRES.

In literature, the possibility that patient with spontaneous IH could develop dural sinus thrombosis favoured by the engorgement of venous system and compensatory venous hypervolemia has been documented [11]; but to the best of our knowledge, the possible role played by IH in the pathogenesis of PRES has never been reported. This condition, despite its manifestations, may be fully reversible, with a resolution of MRI alterations and complete clinical recovery, once appropriate treatment is instituted [12].

Even if further investigation is required to clarify the relationship between these two entities, physicians should keep in mind that a postpartum headache could be the clinical manifestation of an underlying HI, which in turn could lead eventually to the development of PRES. Therefore the importance of correct recognition and diagnosis of IH/PRES condition, also using MR imaging, is implicit in order to be able to establish an adequate therapy to prevent possible irreversible ischemic brain damage.

References

Mokri B (2003) Headaches caused by decreased intracranial pressure: diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Neurol 16:319–326, 10.1097/00019052-200306000-00011

Cesur M, Alici HA, Erdem AF, Silbir F, Celik M (2009) Decreased incidence of headache after unintentional dural puncture in patients with cesarean delivery administered with postoperative epidural analgesia. J Anesth 23:31–35, 10.1007/s00540-008-0690-7

Sell J, Rupp FW, Orrison W (1995) Iatrogenically induced intracranial hypotension syndrome. AJR 165:1513–1515, 1:STN:280:DyaK28%2Fnt1Oisg%3D%3D

Berroir S, Loisel B, Ducros A et al (2004) Early epidural blood patch in spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Neurology 63:1950–1951, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD2crosFOluw%3D%3D

Ay H, Buonanno F, Schaefer P et al (1998) Posterior leukoencephalopathy without severe hypertension. Utility of diffusion-weighted MRI. Neurology 51:1369–1376, 1:STN:280:DyaK1M%2FjsVWksw%3D%3D

Finocchi V, Bozzao A, Bonamini M, Ferrante M, Romano A, Colonnese C, Fantozzi LM (2005) Magnetic resonance imaging in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: report of three cases and review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet 271:79–85, 10.1007/s00404-004-0622-1

Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B et al (1996) A reversible posterior encephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med 334:494–500, 1:STN:280:DyaK287lslSisQ%3D%3D, 10.1056/NEJM199602223340803

Ducros A, Boukobza M, Porcher R, Sarov M, Valade D, Bousser MG (2007) The clinical and radiological spectrum of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. A prospective series of 67 patients. Brain 130:3091–3101, 10.1093/brain/awm256

Mokri B (2001) The Monro–Kellie hypothesis. Applications in CSF volume depletion. Neurology 56:1746–1748, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3MzmsFejug%3D%3D

Savoiardo M, Minati L, Farina L, De Simone T, Aquino D, Mea E, Filippini G, Bussone G, Chiapparini L (2007) Spontaneous intracranial hypotension with deep brain swelling. Brain 130:1884–1893, 10.1093/brain/awm101

Savoiardo M, Armenise S, Spagnolo P, De Simone T, Mandelli ML, Marcone A et al (2006) Dural sinus thrombosis in spontaneous intracranial hypotension: hypothesis on possible mechanism. J Neurol 253:1197–1202, 10.1007/s00415-006-0194-z

Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B et al (1996) A reversible posterior encephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med 334:494–500, 1:STN:280:DyaK287lslSisQ%3D%3D, 10.1056/NEJM199602223340803

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pugliese, S., Finocchi, V., Borgia, M.L. et al. Intracranial hypotension and PRES: case report. J Headache Pain 11, 437–440 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-010-0226-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-010-0226-z