Abstract

The aim of this study is to compare the psychopathology and the quality of life of chronic daily headache patients between those with migraine headache and those with tension-type headache. We enrolled 106 adults with chronic daily headache (CDH) who consulted for the first time in specialised centres. The patients were classified according to the IHS 2004 criteria and the propositions of the Headache Classification Committee (2006) with a computed algorithm: 8 had chronic migraine (without medication overuse), 18 had chronic tension-type headache (without medication overuse), 80 had medication overuse headache and among them, 43 fulfilled the criteria for the sub-group of migraine (m) MOH, and 37 the subgroup for tension-type (tt) MOH. We tested five variables: MADRS global score, HAMA psychic and somatic sub-scales, SF-36 psychic, and somatic summary components. We compared patients with migraine symptoms (CM and mMOH) to those with tension-type symptoms (CTTH and ttMOH) and neutralised pain intensity with an ANCOVA which is a priori higher in the migraine group. We failed to find any difference between migraine and tension-type groups in the MADRS global score, the HAMA psychological sub-score and the SF36 physical component summary. The HAMA somatic anxiety subscale was higher in the migraine group than in the tension-type group (F(1,103) = 10.10, p = 0.001). The SF36 mental component summary was significantly worse in the migraine as compared with the tension-type subgroup (F(1,103) = 5.758, p = 0.018). In the four CDH subgroups, all the SF36 dimension scores except one (Physical Functioning) showed a more than 20 point difference from those seen in the adjusted historical controls. Furthermore, two sub-scores were significantly more affected in the migraine group as compared to the tension-type group, the physical health bodily pain (F(1,103) = 4.51, p = 0.036) and the mental health (F(1,103) = 8.17, p = 0.005). Considering that the statistic procedure neutralises the pain intensity factor, our data suggest a particular vulnerability to somatic symptoms and a special predisposition to develop negative pain affect in migraine patients in comparison to tension-type patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Between 3 and 4% of the general population suffer from chronic daily headache (CDH) and a quarter to a third of them suffer from medication overuse headache (MOH) ([1–4], see specific European data in [5]).

Psychopathological correlates of CDH have been assessed by various means: personality tests, diagnostic devices, and psychopathologic scales (see reviews in [6–8]). An approach with MMPI [9] reveals a higher number of high scores (over 65) in chronic migraine and analgesic rebound headache patients when compared to episodic migraineurs. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders is high in CDH, mostly in anxiety and mood disorders [10–12]. The use of rating scales confirms this important psychopathological burden in CDH [12] which was reported to be higher in patients with medication overuse [13, 14] who can be considered drug-dependent according to the DSM-IV definition [15].

When assessed by various scales, the quality of life in CDH is reduced [12, 16–19], particularly in transformed migraine patients [17–20]. However, these data are difficult to be transposed into the more recent actual international classification of headache disorders (ICHD) [21] which was completed by the complementary note of the Headache Classification Committee [22]. However, more studies based on accepted classifications (ICDH-2 and DSM-IV R) are needed [23]. Furthermore, recent suggestions have been made to break out the medication overuse headache group (code 8.2) [24, 25].

In this study, we address the following question: in the entire group of patients who have CDH, do patients with migraine symptoms have a different psychopathology and quality of life burden than those with tension-type headache? Our analysis studies three well-defined groups of chronic headache: chronic migraine (CM, code 1.5.1), chronic tension-type headache (CTTH, code 2.3.2), and medication overuse headache (MOH, code 8.2). In the last group, using a special clinical analysis, we divided the patients into two subsets, those with migraine symptoms (mMOH) and those with tension-type symptoms (ttMOH).

Method

This study was planned during the year 2000 and patients were enrolled between September 2001 and July 2002. We used the CTTH definition of ICHD-II and the proposals of the Headache Classification Committee (2006) for chronic migraine (CM) and MOH [22, 23]. Patients who had symptomatic headache and trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgia were excluded.

Population and sub-groups

Headache classification

We enrolled 106 patients (75 females and 31 males) with a mean age of 47 years (range 17–83 years, mean 46.9 ± 15.5) who had consulted a neurologist, either in a liberal office (5 investigators), or in an outward consultation in an University Hospital (5 investigators),in the West of France (West Migraine Study Group) for chronic headache, i.e. headache occurring more than 15 days/month for more than 3 months, with attacks lasting more than 4 h when untreated [5]. All patients gave prior, informed consent as recommended by the Tours University Hospital ethical committee. Two pre-inclusion investigator rating sessions were organised in order to homogenise the evaluations.

Each participating physician filled out a questionnaire which took into account the characteristics of the headache(s) reported by the patients. An algorithm automatically determined the classification of the headache. Thus, a given patient could theoretically report several types of headache and a given headache could receive several different ICHD-II codes. Headache which met criteria for both probable migraine (PM) (ICHD-II, code 1.6.1) and tension-type headache (TTH) was classified as TTH according to rule # 5 of the ICHD-II. In each patient, we computed the number of days per month he or she suffered for each type of headache and specified the medications taken during the last 3 months; when necessary medical files were used to determine if patients filled ICHD-II criteria for MOH. The final classification identified 80 MOH patients, 8 chronic migraine (CM) patients, and 18 CTTH patients.

For the needs of the study, MOH patients were divided into two sub-groups: mMOH and ttMOH.

-

(1)

mMOH, if they also fulfilled the criteria for chronic migraine (i.e. precisely, code 1.5.1 criteria A, B, and C according to the Headache Classification Committee (2006)) with the exception of drug abuse. We included patients into this subset who fit the diagnostic of probable migraine, in other words, code 1.1 criteria B or D (IHS classification 2004).

-

(2)

ttMOH, if they fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for chronic tension-type headache (i.e. code 2.3 A–D criteria, IHS classification 2004) with the exception of the drug abuse.

Using this procedure, among the 80 MOH patients enrolled in the study cohort, 43 were classified in the mMOH group and 37 into the ttMOH group. It should be noted that four patients had mMOH between 8 and 15 days per month in addition to 15 days or more with ttMOH headache and were consequently classified in the mMOH group by analogy with the Headache Classification Committee (2006) position concerning chronic migraine criteria (code 1.5.1). Furthermore, one patient had mMOH for 5 days and headache with ttMOH characteristics for 12 days and was classified as ttMOH.

Description of the sub-groups

The demographic characteristics of the four sub-groups included the number of patients in each group, their ages, body mass index, the age at which they left school, marital status, and known previous psychiatric disorders and are summarised in Table 1.

This table also includes the patients’ previous stressful life events. To this end, we used the Amiel Lebigre [26] questionnaire, which, according to the author, is constructed from previous life event scales [27, 28]. Patients were asked to rate from 1 to 100 the impact of 52 precise stressful life events (+one open) on their lives. The authors consider that a global score greater than 200 is suggestive of depression. For the study, the interviewers asked the patients to focus on the period during which the headache became chronic.

Finally, we considered the pain intensity factor associated with the headache, which, a priori, is lower in patients with tension-type headache (level light or moderate, IHS criteria 2.1.C), in contrast to patients with migraine headache (level moderate or severe criteria 1.1.C) is may be used for inclusion. To this end, we established a pain index composed by the sum of the number of days with headache multiplied by a semi-quantitative evaluation of the pain intensity (0 to 3) during these days over last 3 months.

Psychopathological and quality of life scales

-

1.

The tendency for depression was evaluated by using the Montgomery and Asberg Depression Scale (MADRS) [29], a commonly used scale derived from the Comprehensive Psychiatric Rating Scale which contains 10 items (apparent and reported sadness, inner form, reduced sleep and appetite, concentration difficulties, lassitude, inability to feel, pessimistic, and suicidal thoughts) rated from 0 to 6. A total cut-off score of 15 may differentiate depressive subjects; a score of 20 is usually required for inclusion into therapeutic trials [30].

-

2.

The severity of the anxiety symptoms was evaluated with the Hamilton anxiety scale HAMA (Hamilton anxiety) which consists in 14 items rated from 0 to 4: anxious mood, tension, fears, insomnia, intellectual, depressed mood, somatic complaints, muscular or somatic complaints, sensory, cardiovascular symptoms, respiratory symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, genitourinary symptoms, autonomic symptoms, and behaviour during the interview [31]. A global score greater than 20 is usually required for inclusion into therapeutic trials. The authors consider two sub-scales: psychic anxiety (items 1–6 and 14) and somatic anxiety (items 7–13, underlined supra).

-

3.

Quality of life was evaluated by using the SF-36, a self-administered, 36-item questionnaire that measures health-related functions in eight domains : physical functioning (PF), role physical (RP), body pain (BP), general health perception (GH), vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), role emotional (RE), and mental health (MH) [32]; data from a control population, adjusted for gender and age, are reported in Table 3 [33]. These domains are summarised by the mental component summary (MCS) and the physical component summary (PCS) which are loaded differently from the height domain sub-scores; the score of these mental and physical component summaries is about 50 [34] in a control population.

Statistical methods

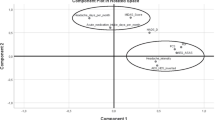

To limit the number of comparisons, we selected five variables which are widely used in the literature: the MADRS global score, the two HAMA sub-scales (HAMA psy, HAMA phy), and the two SF 36 dimension MCS and PCS.

Due to the different number of patients in each sub-groups, we carefully pooled our study patients in two different groups according to the clinical type of headache i.e. patients with migraine symptoms versus patients with tension-type symptoms by pooling CM and mMOH patients into a migraine group (n = 51) and CTT and ttMOH patients into a tension-type group (n = 55). To exclude pain intensity, which is a predicted confusion-factor, we used an ANCOVA to control the pain index, after testing for the non-heterogeneity of the variance with a Levene’s test. When significant differences were present, we performed further explanatory comparisons using the same methodology.

Results (Tables 1 and 2)

The MARDS mean global score was less than 20 in each of the four sub-groups and did not differ significantly between the migraine and tension-type groups (see details in Table 2).

The HAMA mean global score was high in CM (21.6 ± 9.0) and remained below 20 in CTTH (15.6 ± 9.7), mMOH (16.3 ± 8.5), and in ttMOH (12.4 ± 7.5) subgroups. The HAMA psychological and somatic sub-scores are reported in Table 2. These sub-scores were constantly higher in CM and mMOH than in CTTH and ttMOH sub-groups. However, the statistical comparison between the migraine and tension-type groups showed a significant difference only for the somatic HAMA subscale (p = 0.001 see Table 2).

The SF 36 physical and mental component summary scores are reported in Table 2. Scores were always lower (therefore the patients were more disabled) in the CM sub-group and all the scores were lower than the scores seen in the general population (which is about 50): comparison between migraine and tension-type groups revealed that the mental component summary was lower in the migraine group (p = 0.018 see Table 2).

To explain these differences, we considered the eight SF36 domain scores according to clinical sub-groups (see Table 3). With the exception of physical functioning, sub-scale scores were often 20 points lower than control scores and were constantly lower in the CM sub-group. However, comparison between tension-type and migraine groups only revealed significant differences in two domains, which were lower in the migraine group: mental health (MH, p = 0.005) and bodily pain (BP, p = 0.036)

Discussion

Our data focus on the fact that, among patients who suffer from chronic daily headache, there is a difference between patients with migraine symptoms and those with tension-type headache symptoms. Our data indicate that the tendency towards anxiety, already reported in chronic daily headache, is mostly manifested by the somatic symptoms reported by patients with migraine symptoms whether or not they are drug-abusers. Indeed, the HAMA somatic sub-scale, which is significantly different in patients with and without migraine symptoms, is composed of seven items related to somatic symptoms (two general somatic, one cardiovascular, one respiratory, one gastro-intestinal, one sexual and urinary, and one autonomic). This propensity for headache patients to express somatic symptoms had been already reported with other psychological tools [35, 36]; our data suggest that in the whole group of CDH, the anxiety increase is rather due to the somatic anxiety of the patients with migraine symptoms. This raises the following questions: do migraine symptoms have a particular propensity to induce somatic anxiety, or does somatic anxiety increase the occurrence of a migraine symptoms? Interestingly our data do not suggest a high level of somatic and psychological anxiety in the two subgroups with medication overuse (see Table 2), which lead to discuss two hypothesis: either a special trait of MOH patients or, an anxiolytic effect of the drug abuse itself.

The raw SF 36 height domain data suggest that all categories of chronic daily headache patients have an excessively low quality of life. In our cohort as well as in others’ [17, 37], all domains of the SF 36 except one (physical functioning) were significantly affected in the four groups of patients; in addition, the mean scores were often 20 to 40 points different from the scores in historical controls (Table 3). It is not surprising that the Physical Functioning score, which is the result of 10 questions mainly concerned with purely motor performances, is the least-affected domain. Our data strongly suggest a high burden since in this test, a five point difference is considered clinically or socially relevant [38]. The control group is based on data obtained from the Oxford Healthy Life Survey (13,042 subjects between 18 and 64 years old, response rate 72% (see details in Ref. [34]). We adjusted the normative data for gender and age in our study. The severity of the quality of life impairment is also suggested by the historical comparison of SF 36 performed in epileptic patients who reported more than one seizure per month [39] and who seemed to be less affected in all domains.

When considering the impairment in global quality of life, the SF36 mental domain and more precisely, the mental health and the bodily pain dimensions are significantly more impaired in patients with migraine symptoms than in those with tension-type symptoms. Bodily Pain may be considered to represent a measure of the discomfort induced by repeated pain and Mental Health as the inability to feel that one has a healthy psychic functioning. These data are worth considering since the factor intensity of pain is supposedly neutralised by the statistical procedure. One interpretation could be that, confronted with a pain of equivalent intensity, migraine patients are particularly vulnerable as compared to tension-type patients. If we integrate our data with the biological–psychological–social framework of headache as developed by Nicholson et al. [40], we can also hypothesise that among chronic daily headache patients, those with migraine symptoms may have either a greater predisposition to developing negative pain-related affects, or an higher vulnerability to quality of life discomfort.

Some aspects of our study deserve confirmation in future studies. Previous stressful life events may be more prevalent in CM patients and may deserve to be specifically studied. Previous psychiatric disorders need to be analysed with a systematic and comprehensive tool. The depressive tendency of our patients, evaluated by the mean MADRS score, did not reach a level usually considered to represent overt pathology [41] in each sub-groups. This data differ from Mitsikostas and Thomas findings [13]; they compared several headache sufferer subsets and found that the “drug abuse headache group” had the highest mean score in the Hamilton Depression Scale and even reached a pathological level. This point is important if we consider that some previously cited reports showed an increase in mood disorders in CDH [10, 11, 14]. The level of medication overuse may account for part of these apparent discrepancies: the patients of our group were included according to the most recent ICHD 2004/2006(code 8.2) definition, which requires a regular intake of opiates alone or in combination for 10 days/month or more and for 15 days/month or more when other analgesics are taken. The patients in the previous cohorts had a more frequent medication intake since they were recruited either according to the 1988 IHS classification (code 8.2-4) [42] in which daily analgesic use is mandatory or when they took drugs for 18 days/month or more [15]. It seems likely that when drug abuse is greater, the mean depressive level is higher.

Our study is limited by some methodological drawbacks which need to be discussed. Our selected and heterogeneous cohort can hardly be considered to represent CDH in the general population, but we may hypothesise that the psychopathological problems reported by patients in our study cohort somewhat reflect the psychopathological problems seen in CDH patients in general, whatever the mode of selection. Selecting purely CM patients is difficult since they often abuse medication; specific studies are needed in this sub-group since their scores were highly pathological if we consider the scores they obtained in all the evaluation scales. The use of spontaneous patient recall, which induces an obvious bias in historical items and the number of days with a given type of headache combined with the small size of the CM group, suggests that this study needs to be repeated with a larger patient cohort and the use of a diary before inclusion. The overlap of a limited number of patients does not invalidate our study although it does reduce the strength of the analysis.

Abbreviations

- CDH:

-

Chronic daily headache

- IHS:

-

International Headache Society

- ICHD-II:

-

International Classification of Headache Disorders-II

- CTTH:

-

Chronic tension type headache

- CM:

-

Chronic migraine

- MOH:

-

Medication overuse headache

- PM:

-

Probable migraine

- TTH:

-

Tension type headache

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- MADRS:

-

Montgomery and Asberg depression scale

- HAMA:

-

Hamilton anxiety

- SF-36:

-

MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36)

- PF:

-

Physical functioning

- RP:

-

Role physical

- BP:

-

Bodily pain

- GH:

-

General health perception

- VT:

-

Vitality

- SF:

-

Social functioning

- RE:

-

Role emotional

- MH:

-

Mental health

References

Castillo J, Munoz P, Guitera V, Pascual G (1999) Epidemiology of chronic daily headache in the general population. Headache 39:190–199, 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1999.3903190.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD2cnjslCrtg%3D%3D, 15613213

Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Lu SR, Liu CY, Hsu LC, Wang PN, Liu HC (2000) Chronic daily headache in Chinese elderly. Prevalence, risk factors, and biannual follow-up. Neurology 54:314–319, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3c7jt1WhsQ%3D%3D, 10668689

Lu S-R, Fuh J-L, Chen W-T, Juang K-D, Wang S-J (2001) Chronic daily headache in Taipei, Taiwan: prevalence follow-up and outcome predictors. Cephalalgia 21:980–986, 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2001.00294.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD387isVeluw%3D%3D, 11843870

Lantéri-Minet M, Auray JP, El Hasnaoui A, Dartigues JF, Duru G, Henry P, Lucas C, Pradalier A, Chazot G, Gaudin A-F (2003) Prevalence and description of chronic daily headache in the general population in France. Pain 102:143–149, 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00348-2, 12620605

Radat F, Swendsen J (2005) Psychiatric co-morbidity in migraine: a review. Cephalalgia 25:165–178, 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00839.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD2M%2FmtVyqsw%3D%3D, 15689191

Stovner LJ, Zwart J-A, Hagen K, Terwindt GM, Pascual J (2006) Epidemiology of headache in Europe. Eur J Neurol 13:333–345, 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01184.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD283jslSmtw%3D%3D, 16643310

Pompili M, Di Cosimo D, Innamorati M, Lester D, Tatarelli R, Martelletti P (2009) Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with chronic daily headache and migraine: a selective overview including personality traits and suicide risk. J Headache Pain 10:283–290, 10.1007/s10194-009-0134-2, 19554418

De Filippis S, Erbuto D, Gentili F, Innamorati M, Lester D, Tatarelli R, Martelletti P, Pompili M (2008) Mental turmoil, suicide risk, illness perception, and temperament, and their impact on quality of life in chronic daily headache. J Headache Pain 9:349–357, 10.1007/s10194-008-0072-4, 18953488

Bigal ME, Rapoport AM, Lipton RB, Tepper SJ, Sheftell FD (2003) Assessment of migraine disability using the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire. A comparison of chronic migraine with episodic migraine. Headache 43:336–342, 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03068.x, 12656704

Verri AP, Proietti CA, Galli C, Granella F, Sandrini G, Nappi G (1998) Psychiatry comorbidity in chronic daily headache. Cephalalgia 18:45–49, 9533671

Juang Kd, Wang SJ, Fuf JM, Lu SR, Su TP (2000) Comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders in chronic daily headache and its sub types. Headache 40:818–823, 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00148.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3M7jvFaluw%3D%3D, 11135026

Holroyd K, Stensland M, Lipchik G, Hill K, O’Donnel F, Cordingley G (2000) Psychosocial correlates and impact of chronic tension-type headache. Headache 40:3–16, 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00001.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3c3itlemsQ%3D%3D, 10759896

Mitsikostas D, Thomas A (1999) Comorbidity of headache and depressive disorders. Cephalalgia 19:211–217, 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1999.019004211.x, 1:STN:280:DyaK1MzgsVCmsQ%3D%3D, 10376165

Radat F, Sakah D, Lutz G, El Amrani M, Ferrei M, Bousser MG (1999) Psychiatric co-morbidity is related to headache induced by chronic substance use in migraineurs. Headache 39:477–480, 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1999.3907477.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3M7ovFWksA%3D%3D, 11279930

Radat F, Creac’h C, Guegand-Massardier E, Minck G, Guy N, Fabvre N, Giraud P, Nachit-Ouinekh F, Lanteri-Minet M (2008) Behavioral dependance in patients with medication over-use headache: a cross sectional study in consulting patients using the DSM-IV criteria. Headache 46:1026–1036, 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00999.x

Monzon MJ, Lainez MJ (1998) Quality of life in migraine and chronic daily headache patients. Cephalalgia 18:638–643, 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1998.1809638.x, 1:STN:280:DyaK1M%2FpsVWluw%3D%3D, 9876889

Wang S-J, Fuh J-L, Lu S-R, Juang K-D (2001) Quality of life differs among headache diagnoses: analysis of SF 36 survey in 901 headache patients. Pain 89:285–292, 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00380-8, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3M7psFCksw%3D%3D, 11166485

Cassidy E, Tomkins E, Hardiman O, O’Kean V (2003) Factors associated with burden of primary headache in a speciality clinic. Headache 43:638–644, 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03106.x, 12786924

Wiendels NJ, van Haestregt A, Knuistingh Neven A, Spinhoven P, Zitman FG, Assendelft WJ, Ferrari MD (2006) Chronic frequent headache in the general population: comorbidity and quality of life. Cephalalgia 26:1443–1450, 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01211.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD28notFGltw%3D%3D, 17116094

Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Sliwinski M (1996) Classification of daily and near-daily headaches: field trial of revised IHS criteria. Neurology 4:871–875

Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society (2004) The International classification of headache disorders, 2nd ed. Cephalalgia 24(suppl 1):1–160

Headache Classification Committee, Olesen J, Bousser M-G, Diener H-C, Dodick D, First M, Goadsby PJ, Göbel H, Lainez MJA, Lance JW, Lipton RB, Nappi G, Sakai F, Schoenen J, Silberstein SD, Steiner TJ (2006) New appendix criteria open for a broader concept of chronic migraine. Cephalalgia 26:742–746, 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01172.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD283mt1Gruw%3D%3D, 16686915

Lake AE III, Rains JC, Penzien DB, Lipchik GL (2005) Headache and psychiatric comorbidity: historical context, clinical implications, and research relevance. Headache 45:493–506, 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05101.x, 15953266

Bigal ME, Rapoport AM, Sheftell FD, Tepper SJ, Lipton RB (2007) The international classification of headache disorders revised criteria for chronic migraine—field testing in an headache speciality clinic. Cephalalgia 27:230–234, 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01274.x

Ferrari A, Coccia C, Sternieri E (2008) Past, present and future prospects of medication over-use headache classification. Headache 48:1096–1102, 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.00919.x, 18687082

Amiel-Lebigre F (1986) Evènements de la vie et determination de populations à risque de trouble mental. Psychosomatique 6:35–40

Holmes TH, Rahe RH (1967) The social readjustment rating scale. J Psychosom Res 11:213–218, 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4, 1:STN:280:DyaF1c%2FltVeisw%3D%3D, 6059863

Cochrane C, Robertson A (1973) The life events inventory: a measure of the relative severity of psychosocial stressors. J Psychosom Res 17:135–139, 10.1016/0022-3999(73)90014-7, 1:STN:280:DyaE2c%2FgtlemsQ%3D%3D, 4741684

Maier W, Philipp M (1979) Comparative analysis of observer depression scales Brit. J Psychiatry 134:382–389, 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382

Montgomery SA, Asberg M (1979) A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 134:382–389, 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382, 1:STN:280:DyaE1M7ovVCksg%3D%3D, 444788

Hamilton M (1959) The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 32:50–55, 1:STN:280:DyaG1M%2FmvVWisQ%3D%3D, 13638508

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30:473–483, 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002, 1593914

Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Wright L (1993) Short Form 36(SF 36) health survey questionnaire,: normative data for adults of working age. Br Med J 306:1437–1440, 10.1136/bmj.306.6890.1437, 1:STN:280:DyaK3s3pvFahtw%3D%3D

Jenkinson C, Stewart-Brown S, Petersen S (1999) Assessment SF-36 version in the United Kingdom. J Epidemiol Community Health 53:46–50, 10.1136/jech.53.1.46, 1:STN:280:DyaK1M3lsl2jsQ%3D%3D, 10326053

Holm JE, Penzien DB, Holdroyd K, Brown T (1994) Headache and depression: confounding effects of transdiagnostic symptoms. Headache 34:418–423, 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1994.hed3407418.x, 1:STN:280:DyaK2M%2FhtlejsQ%3D%3D, 7928326

Maizels M, Burchette R (2004) Somatic symptoms in headache patients: the influence of headache diagnosis, frequency and comorbidity. Headache 44:983–993, 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04192.x, 15546261

Wiendels NJ, van Haestregt A, Knuistingh Neven A, Spinhoven P, Zitman FG, Assendelft WJ, Ferrari MD (2006) Chronic frequent headache in the general population: comorbidity and quality of life. Cephalalgia 26:1443–1450, 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01211.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD28notFGltw%3D%3D, 17116094

Ware J, snow K, Kosinski M, Gandek B (1993) SF36 Health survey manual and interpretation guide. The Health Institute New England Medical Center Boston, Massachusetts

Baker G, Jakoby A, Buk D, Stalgis C, Monnet D (1997) Quality of life of people with epilepsy; an European study. Epilepsia 38:353–362, 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01128.x, 1:STN:280:DyaK2s3isVSiug%3D%3D, 9070599

Nicholson RA, Houle TT, Jl Rhudie, Norton PJ (2007) Psychological factor in headache. Headache 47:413–426, 17371358

Allgulander C, Florea I, Husom A (2006) Prevention of relapse in general anxiety disorder by Escitalopram treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 9:495–505, 10.1017/S1461145705005973, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BD28XhtFKku73L, 16316482

Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society (1988) Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgia and facial pain. Cephalalgia 8(suppl 7):96

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Astra Zeneca France.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

The members of the West Migraine Study Group are given in the Appendix.

Appendix

Appendix

Allain H, Hinault P, Rennes; Bellard S, Goas JY, Brest; de Bray JM, Dubas F, Verny C, Angers; Feve JM, Magne C, Vercelletto M, Nantes; Merienne JM, Saint Malo; Neau JP, Poitiers; Pinel JF, Rennes; Pouyet A, Saint Brieuc; Schuermans P, La Rochelle; Verret JM, Le Mans.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Autret, A., Roux, S., Rimbaux-Lepage, S. et al. Psychopathology and quality of life burden in chronic daily headache: influence of migraine symptoms. J Headache Pain 11, 247–253 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-010-0208-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-010-0208-1