Abstract

We describe the case of a 40-year-old woman, affected by episodic cluster headache, who presented with a cluster headache triggered by exposure to high altitude. Her attacks were refractory to sumatriptan, very effective at sea level, but responded to oxygen. A pathophysiological mechanism is proposed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cluster headache (CH) is a primary headache, classified into 2 subforms [1]: episodic (ECH 3.1.1) and chronic (CCH 3.1.2). Activation of the ipsilateral hypothalamic region and other regions normally associated with the analysis of painful stimuli (the prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia, thalamus, cingulate cortex, insula and cerebellum) can be demonstrated during CH attacks [2], however, the pathophysiology of CH remains unclear. For the acute treatment of CH attacks, in both subforms, oxygen inhalation (100%) with a flow rate of at least 7 l/min over 15 min and 6 mg subcutaneous sumatriptan are first choice treatments [3]. It has been reported that exposure to hyperbaric oxygen can effectively interrupt a cluster headache attack and to prevent the recurrence over 2 to 3 days following treatment [4]. However, recent Cochrane review suggests that there is insufficient evidence for the use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in acute treatment of CH, and there are thus no convincing reasons to prefer this treatment over normobaric therapy [5].

Although a recent investigation aimed to identify predictors of efficacy for CH treatment with oxygen versus triptans, a possible role for altitude was not considered [6].

Case report

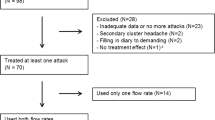

We report the case of a 40-year-old woman who had suffered, since she was aged 25 with ECH. These typically recurred in 1 or 2 clusters per year (December–January and June–July), each lasting about 3 weeks. There were 1–2 attacks/day; these abated within minutes of receiving an injection of 6 mg sumatriptan sc. In 2008, she was traveling by car toward the mountains where she intended to vacation. A typical CH attack began at about 1,400 m of altitude that she reached via a rapidly-ascending road. This was the first time she had been exposed to high altitude during a cluster period. She immediately attempted to treat her attack via sumatriptan injection; this was without success and the injection was repeated once after 5 min, also without remission. However, the attack was over about 35 min by which time she reached her destination, a village at an altitude of 1,500 m. The following day she complained of two further attacks, which again failed to respond to sc sumatriptan. Repeated blood pressure measurements gave normal values. One of us (E.M.) was contacted for assistance. Therapy was started immediately with oral prednisone 60 mg/day associated with verapamil tablets 160 mg/day, medications stated by the patient to have been effective in other similar instances. She was also instructed to try the inhalation of 100% oxygen, 7 l/min by facial mask for 15 min, a therapy she had not previously experienced. Oxygen was procured from a local pharmacy, and the next attack was therefore treated with oxygen. This obtained complete remission within about 5 min. This rapid result was also obtained in further recurrent attacks taking place over the next 5 days while she remained at altitude; sumatriptan was not administered again. After this week she returned to her hometown, situated at the sea level. The day following her return she complained an attack that was treated with sc sumatriptan, this time with a rapid remission. Recurrent attacks over the following days were treated successively with sc sumatriptan and/or oxygen inhalation, and progressively diminished in frequency, and ceased about 7 days later. The patient completed the short-term prophylaxis with prednisone (about 15 days) and continued long-term prophylaxis with verapamil for about one month after the last attack. At follow-up 8 months later she did not report further attacks.

Discussion

Pivotal treatments in acute CH attacks are oxygen and sumatriptan. Previous literature reports indicate that about 60% of CH patients respond to oxygen with a substantial pain reduction within 20–30 min, a higher response rate has been reported with sumatriptan (about 75%) [7]. The standard treatment with oxygen is inhalation (100%), with a flow of at least 7 l/min over 15 min [3], but some evidence suggests that a higher flow rate (15 l/min) can further improve the efficacy [8].

A recent study investigating the possible predictors of treatment responses to oxygen versus sumatriptan in CH patients, found that younger age predicted a successful triptan response, while nausea/vomiting as well as restlessness negatively predicted a successful response to oxygen therapy. In univariate analysis, the efficacy of oxygen was not predicted by the efficacy of triptans and vice versa [6]. This study also found no positive predictors of oxygen treatment efficacy, although a possible role of altitude was not considered [6]. An Ethiopian epidemiological study [9] on a highlands rural community found that CH prevalence was significatively lower than the mean prevalence in western countries [10, 11] suggesting that chronic hypoxia, with subsequent adaptation, does not play a significant role in triggering CH. Nevertheless, this study had some technical limitations and low prevalence may not be specifically attributed to high altitude. Indeed, Kudrow [12, 13] has reported that acute altitude and/or hypoxia can both act as triggers for CH attacks.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of excellent therapeutic action of oxygen inhalation in CH attacks occurring at relatively high altitude. In the present case, sc sumatriptan was very effective in treating CH at sea level, but this medication appeared wholly ineffective at high altitude. Also there are no previous reports addressing the use of oxygen in CH cases refractory to sumatriptan or, conversely, of sumatriptan efficacy in oxygen-refractory CH cases.

What could be the explanation of the fact that sc sumatriptan lost its effectiveness at moderately high altitude? Goadsby and Edvinsson [14] showed that both sumatriptan and oxygen could normalize elevated calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) levels in jugular vein blood during acute CH attacks, and, thus, stopped the activation of the trigeminovascular system. In addition, Huber and Lampl [15] reported, in a single patient, that oxygen relieved both pain and cutaneous cold and brush allodynia within CH attacks; sumatriptan was not tried.

Both oxygen and sumatriptan are considered to mediate therapeutic effects in CH through their vasoconstrictive action [16–20]. Whereas sumatriptan is known to act as an agonist of 5-hydroxy-triptamine1B receptors (5HT-1B) located on the vascular wall [20], but it is not clear whether the effects of oxygen action are direct or are receptor-mediated. Previous work has indicated that multiple mechanisms govern local cerebral blood flow; the parenchyma, the cerebrovascular endothelium, specific brain O2-sensitive neurons and perhaps also the red blood cells have all been suggested to play regulatory roles [21].

Recent experimental evidence has addressed the mechanism of action of oxygen in CH. Oxygen was not found to exert any direct effect on trigeminal afferents, but instead acts specifically on the parasympathetic/facial nerve projections to the cranial vasculature so as to inhibit both evoked trigeminovascular activation and activation of the autonomic pathway during CH attacks. Moreover, these studies have begun to establish a new laboratory model for the most painful primary headache syndrome known—cluster headache [22].

In the case reported here, we hypothesize that exposure to high altitude further stimulated vasodilation, making the receptor-mediated action of sumatriptan inadequate. In this case, where oxygen supplementation maintained its therapeutic effect on CH while the condition failed to respond to sumatriptan, supports the view that the vasoconstriction mediated by oxygen operates through a different regulatory pathway from the HT1B receptor-mediated action of sumatriptan.

In conclusion, we believe that future research on this topic is required to better clarify pathophysiological mechanisms of action of oxygen and sumatriptan in the treatment of CH attacks.

References

Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society (2004) The international classification of headache disorders, 2nd edn. Cephalalgia, vol 24, pp 1–160

Morelli N, Pesaresi I, Cafforio G, Maluccio MR, Gori S, Di Salle F, Murri L (2009) Functional magnetic resonance imaging in episodic cluster headache. J Headache Pain 10:11–14, 10.1007/s10194-008-0085-z, 19083151

May A, Leone M, Àfra J, Linde M, Sàndor PA, Evers S, Goadsby PJ (2006) EFNS guidelines on the treatment of cluster headache and other trigeminalautonomic cephalalgias. Eur J Neurol 13:1066–1077, 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01566.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD28rmt1SgsQ%3D%3D, 16987158

Di Sabato F, Fusco BM, Pelaia P, Giacovazzo M (1993) Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in cluster headache. Pain 52:243–245, 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90137-E, 1:STN:280:DyaK3s3gsFCgug%3D%3D, 8455970

Bennett MH, French C, Schnabel A, Wasiak J, Kranke P (2008) Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3):CD005219, Jul 16

Schürks M, Rosskopf D, de Jesus J, Jonjic M, Diener HC, Kurth T (2007) Predictors of acute treatment response among patients with cluster headache. Headache 47:1079–1084, 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00862.x, 17635600

May A (2005) Cluster headache: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Lancet 366:843–855, 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67217-0, 16139660

Rozen TD (2004) High oxygen flow rates for cluster headache. Neurology 63(3):593, 15304611

Tekle Haimanot R, Seraw B, Forsgren L, Ekbom K, Ekstedt J (1995) Migraine, chronic tension-type headache, and cluster headache in an Ethiopian rural community. Cephalalgia 15:482–488, 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1995.1506482.x, 1:STN:280:DyaK28zhsl2quw%3D%3D, 8706111

Tonon C, Guttmann S, Volpini M, Naccarato S, Cortelli P, D’Alessandro R (2002) Prevalence and incidence of cluster headache in the Republic of San Marino. Neurology 58:1407–1409, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD383ntVKhtQ%3D%3D, 12011291

Sjaastad O, Bakketeig LS (2003) Cluster headache prevalence. Vågå study of headache epidemiology. Cephalalgia 23:528–533, 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00585.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3svns1Ghtg%3D%3D, 12950378

Kudrow L, Kudrow DB (1990) Association of sustained oxyhemoglobin desaturation and onset of cluster headache attacks. Headache 30:474–480, 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1990.hed3008474.x, 1:STN:280:DyaK3M%2FjsVKruw%3D%3D, 2121667

Kudrow L (1994) The pathogenesis of cluster headache. Curr Opin Neurol 7:278–282, 10.1097/00019052-199406000-00017, 1:STN:280:DyaK2czmt12hug%3D%3D, 8081523

Goadsby PJ, Edvinsson L (1994) Human in vivo evidence for trigeminovascular activation in cluster headache. Neuropeptide changes and effects of acute attacks therapies. Brain 117:427–434, 10.1093/brain/117.3.427, 7518321

Huber G, Lampl C (2009) Oxygen therapy influences episodic cluster headache and related cutaneous brush and cold allodynia. Headache 49:134–136, 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01187.x, 18624708

Janks JF (1978) Oxygen for cluster headaches. JAMA 16:191, 10.1001/jama.239.3.191b

Sakai F, Meyer JS (1979) Abnormal cerebrovascular reactivity in patients with migraine and cluster headache. Headache 19:257–266, 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1979.hed1905257.x, 1:STN:280:DyaE1M3jvV2htA%3D%3D, 468531

Drummond PD, Anthony M (1985) Extracranial vascular responses to sublingual nitroglycerin and oxygen inhalation in cluster headache patients. Headache 25:70–74, 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1985.hed2502070.x, 1:STN:280:DyaL2M7ot1Srtg%3D%3D, 3921490

Hardebo JE, Messeter K, Ryding E (1989) Observations on mechanism behind the beneficial effect of oxygen on cluster headache. In: Clifford Rose F (ed) New advances in headache research. Smith-Gordon, London, pp 221–228

The Sumatriptan Cluster Headache Study Group (1991) Treatment of acute cluster headache with sumatriptan. N Engl J Med 325:322–326

Floyd TF, Clark JM, Gelfand R, Detre JA, Ratcliffe S, Guvakov D, Lambertsen CJ, Eckenhoff RG (2003) Independent cerebral vasoconstrictive effects of hyperoxia and accompanying arterial hypocapnia at 1 ATA. J Appl Physiol 95:2453–2461, 12937024

Akerman S, Holland PR, Lasalandra MP, Goadsby PJ (2009) Oxygen inhibits neuronal activation in the trigeminocervical complex after stimulation of trigeminal autonomic reflex, but not during direct dural activation of trigeminal afferents. Headache 49:1131–1143, 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01501.x, 19719541

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mampreso, E., Maggioni, F., Viaro, F. et al. Efficacy of oxygen inhalation in sumatriptan refractory “high altitude” cluster headache attacks. J Headache Pain 10, 465–467 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-009-0160-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-009-0160-0