Abstract

Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache (SUNCT) and first division trigeminal neuralgia (TN) are rare and very similar periorbital unilateral pain syndromes. Few cases of SUNCT are associated with posterior skull lesions. We describe a 54-year-old man with symptoms compatible with both the previous painful syndromes, associated with a small posterior skull and a cerebellar hypoplasia. The short height and the reported bone fractures could be compatible with a mild form of osteogenesis imperfecta, previously described in one case associated with SUNCT. However, a hypoplastic posterior cranial fossa characterizes also Chiari I malformation. The difficult differential diagnosis between SUNCT and TN and their relation with posterior skull malformations is debated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache (SUNCT) is a rare form of trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia (TAC), characterized by neuralgiform pain in the territory innervated by first trigeminal division associated with conjunctival injection and tearing [1]. The prevalence of SUNCT is unknown but it is very rare, notwithstanding some cases may have been misdiagnosed [2]. Approximately 100 cases were reported in the literature. The estimated incidence and prevalence was about 1.2 and 6.6/100,000, respectively [3]. The diagnosis of SUNCT is often confused with another rare syndrome, the first division trigeminal neuralgia (TN) [4]. Few cases of SUNCT are secondary (symptomatic), mainly associated with either posterior skull or pituitary gland lesions [2, 5, 6], although other sites have been documented [2].

In this report, we describe a new case with clinical features resembling SUNCT or TN, associated with a posterior fossa abnormality.

Case report

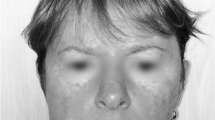

A 54-year-old man (height 148 cm, weight 60 kg) for the last 14 years, at the beginning in concomitance with a period of familiar stress and depression, presented periods of headache attacks of undefined length. The intervals between the four periods were 7, 3 and 2 years, respectively. The latest episode lasted more than a year without remission. He presented a stabbing daily headache located in the left forehead, with single stabs of 7–8 s occurring approximately 12–13 times per hour, with nocturnal prevalence, with ipsilateral conjunctival injection and tearing. At the time of our consultation, the patient did not remember having an attack occurring immediately after the previous one, i.e., the absence/presence of a refractory period. The patient referred ipsilateral miosis, but this was never described by physicians previously consulted. His medical history showed a strabismus in the left eye corrected at age of 4 years and clavicular and malleolar fractures. Repeated clinical and neurological examinations were normal. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium showed a small posterior skull and a cerebellar hypoplasia, without dysplasia, and a straight sinus orientated vertically due to the vertical insertion of tentorium. Aspecific subcortical frontal white matter hyperintensities were present bilaterally. Over the past years, various diagnosis of depression, hypochondria and anxious neurosis were made, and the patient was treated with antidepressant (amitriptyline, fluoxetine and 5-hydroxytryptophan) and anxiolytic drugs without efficacy. In the last episode, treatment with gabapentin (900 mg/day) was ineffective, while treatment with gabapentin associated with carbamazepine (600 mg/day) was effective in eliminating the stabs apart from those in the awakening period.

Discussion

The diagnosis of SUNCT may be confused with TN particularly of the trigeminal nerve first division. The distinction between first division TN and SUNCT is certainly blurred and there is potential for overlap, and some authors consider them to be a single disturbance [7]. There are no clear-cut characterizing differences in age of start, duration of attacks, diurnal variation (presence also in the night), autonomic symptoms, cutaneous triggers, treatment response, presence of aberrant vascular loops potentially irritating the trigeminal nerve (Table 1) [2–4, 8, 9]. Minimal or no cranial autonomic symptoms and a clear refractory period to triggering are believed useful pointers to diagnosis of TN. Indeed, the most distinctive clinical difference is that 95% of SUNCT do not have a refractory period, which means patients could have one attack immediately after cessation of the preceding one [2]. Coexistence of SUNCT and TN in some patients is also described [7, 10]. Differently to TN, in the SUNCT an extratrigeminal pain and an extension into maxillary and mandibular divisions of the trigeminal nerve have not been initially reported [8]. However, in a successive series, SUNCT attacks affecting the second division of trigeminal nerve were described in 33% of cases, and the pain may be experienced anywhere in the head [2].

The symptoms of the presented case are compatible both with SUNCT or TN. Notably, the miosis referred by our patient is sometimes described in SUNCT [8, 11–13]. It was not possible to assess the lack of a refractory period in our patient, which was considered a good clinical feature of SUNCT diagnosis [2] but not more helpful in comparison with other features [3]. Also the good effectiveness of carbamazepine is not necessarily in favor of TN diagnosis. In fact, SUNCT can be very refractory to therapy. There are anecdotal reports of effectiveness of various antiepileptic drugs (carbamazepine, gabapentin, topiramate, etc.) not confirmed in large series [3, 14]. The literature suggests that lamotrigine is the most likely medicine to be effective [3, 15]. However, in assessing the drug effectiveness in episodic SUNCT, a spontaneous and prolonged clinical remission must be taken into account. In fact lamotrigine was ineffective in nine out ten chronic SUNCT treated [3]. It was stated that the failure of SUNCT to respond to carbamazepine is helpful in making the distinction with TN [3]. However, a partial response to carbamazepine was reported in some SUNCT cases [11]. We have not tried lamotrigine in our patient because he responded well to the previous therapy, and his possible chronic SUNCT probably would not have responded to this drug.

The characteristic of the case is the small posterior skull and a cerebellar hypoplasia. It is remarkable that most of the lesions found in association with SUNCT involve the posterior fossa or, in general, the posterior part of the brain [6]. A case of SUNCT associated with osteogenesis imperfecta, characterized by distortion of posterior fossa anatomical relations was described [16, 17]. Osteogenesis imperfecta was also associated to second and third division TN [18–20]. Another case of secondary SUNCT was reported in a patient with craneosynostosis with foreshortened posterior fossa [21].

In addition to the bone deformations, vascular malformations in close to trigeminal root were described in few cases of SUNCT [6, 10, 22]. The symptomatic SUNCT associated with posterior fossa lesions may be due to compression and traction forces at the level of brainstem in close proximity to the trigeminal nerve route entry zone [17]. Contact between vascular structures and the trigeminal nerve has been reported in nearly 90% of patients with SUNCT [3], a percentage similar to that found in TN [2, 10]. Curiously, in a 71-year-old patient of a first division TN series, the MRI showed a marked cerebral and cerebellar atrophy, not present 3 years beforehand at the start of symptoms [4].

We cannot diagnose exactly the cranial malformation of our case report, for the lack of other information. Some inferences, however, can be drawn. The small posterior skull with cerebellar hypoplasia associated with a short height and the bone fractures could be compatible with a mild form of osteogenesis imperfecta, for example a type IV of Sillence’ classification [23]. Theoretically our case report may also be compatible with another bone deformation of the posterior skull, the Chiari I malformation. The most likely explanation of Chiari I malformation is in fact a small (hypoplastic) posterior fossa [24, 25]. The MRI in our patient does not show an extension of the cerebellar tonsils 3–5 mm below the foramen magnum as radiographic criteria required. However, Chiari malformation represents a range of abnormalities and probably a heterogeneous grouping of disorders. The tonsillar ectopia was considered a poor sole criterion for diagnosis. In fact morphological data suggest that some patients exists without tonsillar descent more than 3 mm but with congenitally hypoplastic posterior fossa causing symptomatology consistent with Chiari I malformation without herniation of cerebellar structures into the spinal cord [25]. Chiari IV malformation is characterized by a severe form of cerebellar hypoplasia without herniation of cerebellar structures, but most infants do not survive. Curiously the strabismus, which in our patient was corrected in early childhood, and therefore unlikely related to the development of neuralgiform pain in fifth decade, can be the initial symptom of Chiari 1 malformation [26]. Strabismus was also described in a patient with SUNCT associated with optic nerve hypoplasia [27]. In addition to few reported cases of TN associated with Chiari 1 malformation involving the second and third trigeminal division [28], a case of isolated first division TN without autonomic features was recently described [29]. Moreover, of the few cases of TN (second and third division) associated with paroxysmal hemicrania, a secondary case with Chiari 1 malformation was described [30].

In conclusion, our described case is a patient with neuralgiform pain in the area innervated by the first division of the trigeminal nerve, with conjunctival injection and tearing, associated with a small posterior skull and cerebellar hypoplasia. The clinical characteristics do not permit an exact diagnosis of SUNCT or first division TN for our patient; on the other hand, these rare syndromes can be a unique pathology. Defining and classifying congenital cerebellar abnormalities remains difficult and confusing [24]. The cranial malformation of our case could be compatible with a mild form of osteogenesis imperfecta or a Chiari I malformation.

References

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (2004) The international classification of headache disorders. Cephalalgia 24(Suppl 1):1–160

Cohen AS, Matharu MS, Goadsby PJ (2006) Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT) or cranial autonomic features (SUNA)—a prospective clinical study of SUNCT and SUNA. Brain 129:2746–2760 10.1093/brain/awl202, 16905753

Williams MH, Broadley SA (2008) SUNCT and SUNA: clinical features and medical treatment. J Clin Neurosci 15:526–534 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.09.006, 18325769

Sjaastad O, Pareja IA, Zukerman E, Jansen J, Kruszewski P (1997) Trigeminal neuralgia. Clinical manifestations of first division involvement. Headache 37:346–357 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1997.3706346.x, 1:STN:280:DyaK2szotVKgsQ%3D%3D, 9237408

Levy MJ, Matharu MS, Meeran K, Powell M, Goadsby PJ (2005) The clinical characteristics of headache in patients with pituitary tumours. Brain 128:1921–1930 10.1093/brain/awh525, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD2MzntF2msg%3D%3D, 15888539

Trucco M, Mainardi F, Maggioni F, Badino R, Zanchin G (2004) Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania, emicrania continua and SUNCT syndrome in association with other pathologies: a review. Cephalalgia 24:173–184 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00646.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD2c7hvV2ltw%3D%3D, 15009010

Leone M, Mea E, Genco S, Bussone G (2006) Coexistence of TACS and trigeminal neuralgia: pathophysiological conjectures. Headache 46:1565–1570 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00537.x, 17115989

Pareja JA, Sjaastad O (1997) SUNCT syndrome. A clinical review. Headache 37:195–202 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1997.3704195.x, 1:STN:280:DyaK2s3psV2nsg%3D%3D, 9150613

Pareja JA, Cuadrado ML, Caminero AB, Barriga FJ, Baron M, Sanchez-del-Rio M (2005) Duration of attacks of first division trigeminal neuralgia. Cephalalgia 25:305–308 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00864.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD2M7kt1Wrsg%3D%3D, 15773828

Zidverc-Trajkovic J, Mijajlovic M, Pavlovic AM, Jovanovic Z, Sternic N (2005) Vertebral artery vascular loop in SUNCT and concomitant trigeminal neuralgia. Case report. Cephalalgia 25:554–557 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.00888.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD2MzgvVWnug%3D%3D, 15955046

Schwaag S, Frese A, Husstedt I-W, Evers S (2003) SUNCT syndrome: the first German case series. Cephalalgia 23:398–400 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00551.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3s3ls1elsA%3D%3D, 12780772

Prakash KM, Lo YL (2004) SUNCT syndrome in association with persistent Horner syndrome in a Chinese patient. Headache 44:256–258 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04056.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD2c7it1Kmsw%3D%3D, 15012664

Raudino F (2005) SUNCT: a new case with some unusual features. J Headache Pain 6:459–461 10.1007/s10194-005-0246-2, 16388341

Pareja JA, Kruszewki P, Sjaastad O (1995) SUNCT syndrome: trials of drugs and anesthetic blockades. Headache 35:138–142 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1995.hed3503138.x, 1:STN:280:DyaK2M3jvVWhuw%3D%3D, 7721573

Goadsby PJ, Cittadini E, Burns B, Cohen AS (2008) Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias: diagnostic and therapeutic developments. Curr Opin Neurol 21:323–330 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282fa6d76, 18451717

Triebels HJMV, ter Berg WMH, vd Laan R (1997) SUNCT-syndrome caused by osteogenesis imperfecta: first report. Cephalalgia 17:305

ter Berg JWM, Goadsby PJ (2001) Significance of atypical presentation of symptomatic SUNCT: a case report. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 70:244–246 10.1136/jnnp.70.2.244, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3M7nvFaqsg%3D%3D, 11160478

Reilly MM, Valentine AR, Ginsberg L (1995) Trigeminal neuralgia associated with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 58:665 10.1136/jnnp.58.6.665, 1:STN:280:DyaK2Mzjt1yntQ%3D%3D, 7608661

Hayes M, Parker G, Ell J, Sillence D (1999) Basilar impression complicating osteogenesis imperfecta type IV: the clinical and neuroradiological findings in four cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 66:357–364 10.1136/jnnp.66.3.357, 1:STN:280:DyaK1M7ot1ShtA%3D%3D, 10084535

Hajioff D, Dorward NL, Wadley JP, Crockard HA, Palmer JD (2000) Precise cannulation of the foramen ovale in trigeminal neuralgia complicating osteogenesis imperfecta with basilar invagination: technical case report. Neurosurgery 46:1005–1008 10.1097/00006123-200004000-00048, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3c3isFemsw%3D%3D, 10764281

Moris G, Ribacoba R, Solar DN, Vidal JA (2001) SUNCT syndrome and seborrheic dermatitis associated with craneosynostosis. Cephalalgia 21:157–159 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2001.00183.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3MzmtFOqug%3D%3D, 11422101

Mondejar B, Cano EF, Perez I, Navarro S, Garrido JA, Velasquez JM, Alvarez A (2006) Secondary SUNCT syndrome to a variant of the vertebrobasilar vascular development. Cephalalgia 26:620–622 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01090.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD283ltVCrsg%3D%3D, 16674773

Sillence DO, Senn A, Danks DM (1979) Genetic heterogeneity in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Med Genet 16:101–116 10.1136/jmg.16.2.101, 1:STN:280:DyaE1M3hvVOrtw%3D%3D, 458828

Boltshauser E (2004) Cerebellum—small brain but large confusion: a review of selected cerebellar malformations and disruptions. Am J Med Genet A 126A:376–385 10.1002/ajmg.a.20662, 15098235

Sekula RF Jr, Jannetta PJ, Casey KF, Marchan EM, Sekula LK, McCrady CS (2005) Dimensions of the posterior fossa in patients symptomatic for Chiari I malformation but without cerebellar tonsillar descent. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res 2:11 10.1186/1743-8454-2-11, 16359556

Kowal L, Yahalom C, Shuey NH (2006) Chiari 1 malformation presenting as strabismus. Binocul Vis Strabismus Q 21:18–26 16457660

Theeler BJ, Joseph KR (2009) SUNCT and optic nerve hypoplasia. J Headache Pain. doi:10.1007/s10194-009-0135-1

Papanastassiou AM, Schwartz RB, Friedlander RM (2008) Chiari I malformation as a cause of trigeminal neuralgia: case report. Neurosurgery 63:E614–E615 10.1227/01.NEU.0000324726.93370.5C, 18812944

Caranci G, Mercurio A, Altieri M, Di Piero V (2008) Trigeminal neuralgia as the sole manifestation of an Arnold-Chiari type I malformation: case report. Headache 48:625–627 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.01029.x, 18194301

Monzillo P, Nemoto P, Costa A, Rocha AJ (2007) Paroxysmal hemicrania-tic and Chiari I malformation: an unusual association. Cephalalgia 27:1408–1412 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01362.x, 1:STN:280:DC%2BD2snpsV2ktw%3D%3D, 17944959

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Panconesi, A., Bartolozzi, M.L. & Guidi, L. SUNCT syndrome or first division trigeminal neuralgia associated with cerebellar hypoplasia. J Headache Pain 10, 461–464 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-009-0152-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-009-0152-0