Abstract

Four cochlear implant users, having normal hearing in the unimplanted ear, compared the pitches of electrical and acoustic stimuli presented to the two ears. Comparisons were between 1,031-pps pulse trains and pure tones or between 12 and 25-pps electric pulse trains and bandpass-filtered acoustic pulse trains of the same rate. Three methods—pitch adjustment, constant stimuli, and interleaved adaptive procedures—were used. For all methods, we showed that the results can be strongly influenced by non-sensory biases arising from the range of acoustic stimuli presented, and proposed a series of checks that should be made to alert the experimenter to those biases. We then showed that the results of comparisons that survived these checks do not deviate consistently from the predictions of a widely-used cochlear frequency-to-place formula or of a computational cochlear model. We also demonstrate that substantial range effects occur with other widely used experimental methods, even for normal-hearing listeners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As more patients with residual hearing receive cochlear implants (CIs), there has been increasing interest in the relationship between the neural excitation produced by stimulating an electrode and that produced by a given acoustic stimulus. Here, we study a rare group of patients having completely normal hearing in the unimplanted ear and investigate the locus of excitation along the auditory nerve (AN) array produced by electric and acoustic stimulation. The results may be not only of scientific interest but may also inform the fitting of CIs in cases where some hearing persists in one ear.

Several studies have obtained frequency matches between high-rate (typically >700 pps) pulse trains applied to a single electrode of a CI and pure tones presented to a contralateral ear having some, usually impaired, hearing. Two of these studies (Boëx et al. 2006; Dorman et al. 2007) found that the pure tone matched to stimulation of a given electrode had a frequency that was between one and two octaves lower than Greenwood’s (1990) formula relating cochlear place to characteristic frequency (CF). A similar trend was observed, at least for low-frequency tones, by Blamey et al (1996). More recently, Vermeire et al (2008) found that with patients having normal or near-normal hearing in the unimplanted ear, matches did not deviate consistently from the predictions of Greenwood’s formula.

A number of important issues should be considered when interpreting acoustic-electric pitch comparisons. First, in most studies, patients have had some experience of listening simultaneously through their implanted and unimplanted ears, prior to testing, so acclimatization to the frequency-to-place map of the patient’s CI may influence the results (Reiss et al. 2007; McDermott et al. 2009). Second, most patients have significant hearing loss in the unimplanted ear, which probably damaged the outer hair cells (OHCs) and produced a basalward shift in the peak of the traveling wave (e.g., Liberman 1984; see McFadden 1986, for a review), again affecting the matched pitch. Third, pitch is influenced not only by place-of-excitation cues but also by phase locking in the AN (Burns and Viemeister 1981; Pijl and Schwarz 1995; Carlyon 1997; Zeng 2002). Although phase locking probably influences pitch in normal hearing (“NH”) for frequencies up to at least 2,000 Hz (Moore 1973; Hartmann et al. 1990; Meddis and Hewitt 1991; Micheyl et al. 1998), the pitch of electric pulse trains often increases with pulse rate only up to a few hundred pps (Shannon 1983; Townshend et al. 1987; McKay et al. 2000). This difference in temporal cues could therefore influence electro-acoustic pitch matches, and may be one reason why high-rate electric pulse trains sound qualitatively different from pure tones (McDermott and Sucher 2006). Finally, and most importantly, we shall argue that pitch matches between sounds in the two ears that have different perceptual qualities, as is the case with electric-acoustic pitch matches, are highly susceptible to non-sensory biases that can distort the results obtained.

Here, we report electro-acoustic matches from patients having normal hearing in the non-implanted ear, thereby eliminating effects related to OHC damage. For all patients, a subset of matches were obtained either before they had listened simultaneously to sounds through their implanted and non-implanted ear, and/or after several months where no such simultaneous electric-acoustic listening occurred. Although we did not systematically study the effects of listening experience, this allowed us to obtain some “natural” matches uncontaminated by acclimatization to a particular map. Furthermore, we describe comparisons between low-rate electric and acoustic pulse trains which, we argue, are likely to have produced similar temporal patterns of responses in each ear. We show that, even under such conditions, electro-acoustic matches are susceptible to non-sensory biases and describe some checks that should be performed to test for the presence of such biases. All subjects showed some matches that failed these checks, but, for three out of the four tested, there were also one or more that passed. We then compared these successful matches to the predictions of Greenwood’s formula and of a computational model of the implanted cochlea (Frijns et al. 2001; Briaire and Frijns 2005). Finally, in the Appendix, we demonstrate that non-sensory biases occur even in NH subjects when comparing perceptually different sounds in the two ears, thereby suggesting that such biases are ubiquitous, and underlining the need to check for such biases when studying clinical populations.

Experiment 1

Methods

Subjects

Here we report results obtained from four subjects, all of whom were implanted with the Advanced Bionics HiRes90k device (Table 1). They were implanted as part of a study, which is still ongoing, whose primary aim was to evaluate the usefulness of CIs as a means for alleviating tinnitus (Dauman et al. 2009). Two of them, B1 and B2, were implanted at the Hôpital Pellegrin in Bordeaux, France. Two others, C1 and C2, were implanted at the Addenbrookes NHS Hospital Trust in Cambridge, England. The design of the Tinnitus Study was that patients would spend 3 months in each of two conditions: (1) either listening “normally” through the microphone of their implant (“speech mode”), or (2) with the microphone disabled but with the opportunity to listen to some sounds recorded on an mp3 player and presented through the auxiliary input of their CI. There was a 2-week “washout” period between the two parts of the study. The condition order was counterbalanced across subjects. All subjects had thresholds below 20 dB HL at all audiometric frequencies.

Stimuli

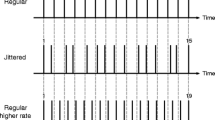

Acoustic stimuli, presented to the normal-hearing ear of each subject, were either pure tones or filtered harmonic complexes whose components were summed in alternating sine-cosine phase, and with a fundamental frequency (F0) of either 6 or 12.5 Hz. Such stimuli resemble pulse trains in which the pulse repetition rate is equal to twice the F0 (i.e., 12 or 25 pps; Patterson 1987; Shackleton and Carlyon 1994)Footnote 1. These low rates were chosen to be below the lower limit of temporal pitch (Krumbholz et al. 2000), thereby minimising any systematic influences of phase locking on the matches obtained. Furthermore, we reasoned that AN fibers would, in both electric and acoustic stimulation, be likely to fire when and only when a pulse occurred, thereby producing similar temporal codes in each ear. The amplitudes of the nine components closest to the filter CF were equal and component amplitude decreased at a rate of 48 dB/octave outside that passband. For both the pure tones and filtered complexes, a large number of stimuli, with (center) frequencies ranging from 250 to 9,944 Hz, in steps of 2%, were generated in advance and stored as waveform files on a laptop computer. The duration of each waveform file was 500 ms, including 10-ms linear ramps. The stimuli were presented via an Edirol UA-25 external sound card and one earpiece of a Sennheiser HD650 headset.

Electric stimuli were 12, 25, or 1,031-pps cathodic-first biphasic pulse trains presented in monopolar mode to one electrode. The phase duration was 32 μs, and the duration of each pulse train was 500 ms, the same as for the acoustic stimuli. Pulse trains were checked using a test implant and a digital storage oscilloscope. Both the acoustic and electric stimuli were presented using the APEX software interface (Laneau et al. 2005), which, in the case of electric stimulation, was modified from the publicly available version to incorporate the “BEDCS” research platform provided by Advanced Bionics.

Procedure

Two methods were used to ensure that, in the main part of the experiment, loudness was approximately constant as a function of center frequency. For the pulse trains, four subjects having normal hearing in both ears were asked to loudness balance twelve 25-pps bandpass filtered pulse trains centered on different frequencies (250; 375; 500; 750; 1,000; 1,500; 2,000; 3,000; 4,000; 6,000; 8,000; and 10,000 Hz). The level of the 10,000-Hz pulse train was set to 80 dB SPL and was used as the reference to balance the 8,000-Hz stimulus. The 8,000-Hz stimulus was then set to the averaged level of four adjustments and the 10,000-Hz stimulus was loudness balanced to it to correct for possible bias due to the order of presentation. For each loudness balance, the level of the adjustable sound could be adjusted for the next trial in steps of ±1, 2, or 6 dB by clicking on “virtual” buttons on the computer screen. Once the level for the 8,000-Hz stimulus was obtained, it was used as a reference to balance the 6,000-Hz stimulus, and so on until the 250-Hz stimulus was adjusted. The waveform files were then scaled appropriately for use by patients in the main part of the experiment by logarithmic interpolation of the levels found in the loudness balancing preliminary experiment. For the pure tones, we used the loudness model described by Moore and Glasberg (1996) to equate loudness across frequency.

For each subject, a set of electrodes spanning the electrode array was arbitrarily selected, with the constraint that they did not have abnormally high impedances and that an analysis of the computed tomography (CT) scans confirmed they were located inside the cochlea. Current levels corresponding to the upper limits of comfort were determined for each electrode, and each electric stimulus was then loudness balanced to a corresponding acoustic sound whose frequency or filter CF was as predicted by CT scan analysis using a cochlear model that we will describe below. The initial set of loudness-balanced acoustic stimuli was set to 70 dB SPL at 1,000 Hz. If this level was too high for subjects to adjust the loudness of the electric pulse train below their upper limit of comfort, it was decreased; the minimum level at 1,000 Hz used was 55 dB SPL for subject B1.

For the main part of the experiment, a number of different methods were used. The aim was not to perform a formal comparison of the different methods, but rather to try different methods for each subject in an attempt to minimise non-sensory effects. A further reason for this approach was that the matches obtained soon after implantation were used to inform the frequency-to-electrode map that the patient was fitted with; those maps usually involved a compromise between an appropriate pitch match and the desire not to drop too much low-frequency information. For each method, we alternated between obtaining measurements with two different electrodes and/or stimuli (pure tone vs. pulse trains), in order to minimise the possibility of the subject basing responses on the memory of the previous measure. Trials always consisted of a comparison between either a 1,031-pps pulse train and a pure tone, or of a 12- or 25-pps electric pulse train and an acoustic pulse train of the same rate.

Constant stimuli

In each trial, the subject was presented with an acoustic and an electric stimulus in random order and asked to indicate which had the higher pitch. In each block of trials, the electric pulse train was always the same, and the acoustic stimulus was selected from one of seven or eight stimuli spanning a wide (1.5-2 octave) range in equal logarithmic steps. Ten trials per point were completed for each block, and the subject was then tested on another stimulus. The two stimuli were then tested again but with a different range of acoustic stimuli. The difference in center frequencies between the two ranges was 0.86 octaves for all subjects except B1, for whom it was 0.89 octaves. An exception to this was for electrode 12—the most basal electrode tested—where the range difference was reduced to 0.4 octaves in order to avoid exceeding the range of center frequencies in our wave files. This procedure was then repeated until a total of 30 trials per point had been completed for each combination of range and stimulus. The point of subjective equality (PSE), corresponding to the 50% point on the psychometric function, was determined by probit analysis (SPSS, 2008).

For one subject, C1, a set of additional measures was obtained with the level of the acoustic stimuli reduced by 25 dB, and with the level of the electric stimuli re-balanced in loudness to them. For each electrode tested, we measured a psychometric function with 10 trials/point with the reduced level, alternating with blocks at the original higher level, in the following order: (low level, range 1)—(high level, range 2)—(low level, range 2)—(high level, range 1). This was then repeated twice more in the same order to give 30 trials per point.

Interleaved adaptive procedures

In each trial, subjects were presented with an electric and an acoustic stimulus and asked to judge which was higher in pitch. Each block of trials consisted of two interleaved adaptive procedures ("tracks": Jesteadt 1980), which converged on points where the acoustic stimulus was judged higher than the electric stimulus on 29% and 71% of trials, respectively. The PSE was estimated from the geometric means of these two values. The initial (center) frequencies of the acoustic stimuli used for the two tracks differed by 2 octaves. For both tracks, the change from increasing to decreasing frequency or vice versa was called a turnpoint, and the procedure ended after eight turnpoints. The acoustic frequency step size was reduced from 22% to 8% after four turnpoints. The value for each track was estimated from the geometric mean of the last six turnpoints. The probability of presenting the upper or the lower track on a given trial was initially 50%. In order to reduce the chances of one track ending long before the other, this probability was then adjusted as follows. If one track was two turnpoints ahead of the other, its probability of presentation switched to 40% (and 60% for the “late” track). Similarly, if one was four turnpoints ahead, its probability switched to 20% (and 80% for the late track). When both tracks were completed, the procedure was repeated for another condition. These two conditions were then repeated but with the starting values for the two procedures shifted by 0.86 octaves (0.4 octaves for electrode 12). The whole procedure was repeated until the subject had completed three sets of adaptive procedures for each set of starting values.

Pitch matching by adjustment

In each trial of each pitch-matching run, the subject was presented with an electric pulse train followed, 500 ms later, by an acoustic stimulus presented to the other ear. The (center) frequency of the acoustic stimulus to be presented on the next trial could then be adjusted by a factor of 2%, 8%, or 37% up or down by clicking on one of six virtual buttons on a computer screen, labelled “+++”, “++”, “+”, “-”, “- -”, and “- - -”, respectively. The subject was encouraged to “bracket” the match, and, when satisfied, could end the run by pressing a seventh button. Eight matches were obtained for each condition, and the starting frequencies used for each match were selected at random; the range of values used for a given condition varied between one and 2 octaves. The criteria for choosing the center of this initial range differed across subjects: for B1 and B2 it was equal to that of a sound that gave roughly the same pitch as the electric stimulus, based on informal observations. This is similar to the approach of choosing the range of acoustic sounds that has been adopted for several measurement techniques in previous studies (Boëx et al. 2006; Dorman et al. 2007). For C1 and C2, the center of the range was chosen either from the results obtained previously with the method of constant stimuli, or from the predictions of our computational model of the cochlea.

Determination of each subject’s tonotopy

For all subjects a pre- and postoperative multidetector CT scan was obtained using the parameters given by Verbist et al. (2005; 2008). These scans were used to estimate the frequency alignment of each individual’s electrode array, as computed with a computational model of the implanted cochlea (Frijns et al. 2001; Briaire and Frijns 2005), developed at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands. Patient-specific computational models were created by matching the pre-operative CT scan with scaled versions of one of two basic cochlear shapes. These basic shapes were constructed from histological cross sections. The resulting 3D electrical volume conduction model was combined with an active model of the cochlear nerve. The trajectories of the modeled fibres were defined using data from Stakhovskaya et al. (2007).

The location of the most lateral point of the horizontal semicircular canal was used as a reference point for determining cochlear angles in the model, by assuming the round window was located 34.6º from the line between that point and the central axis of the cochlea (Verbist et al. 2010). Next, a realistic model of the Clarion HiFocus electrode array was positioned in the scala tympani of the individualized cochlea model corresponding with the contact locations from the post-operative CT scan. The locations of the electrode contacts along the basilar membrane of the model were determined to find their corresponding pitch as predicted by the Greenwood map (Greenwood 1990).

Using both the volume conduction model and the active nerve fibre model with this patient-specific geometry, the excitation pattern (EP) of each inserted electrode contact was calculated. Current levels were set to excite the fibres along 4 mm of the basilar membrane, as this is assumed to correspond to MCL (Briaire and Frijns 2006). The predicted pitch was determined by the peripheral ending along the BM of the fiber at the spatial centre of gravity of the EP.

Results

Reliability of matches

In this subsection, we consider the reliability of the pitch comparisons obtained by the various methods, and describe some checks that should be performed when interpreting such measures. The interpretation of matches that pass these checks will be discussed in the next section.

Method of constant stimuli

Figure 1A shows psychometric functions obtained for pitch comparisons between a 1,031-pps pulse train and a pure tone (triangles) and between 25 pps electric and acoustic pulse trains (circles), for patient B1, electrode 6. The two curves on the left, joined by dotted lines, show the data obtained when the (center) frequencies of the acoustic stimuli ranged from 686 to 2,252 Hz. The curves are monotonic, span a wide range of values on the abscissa, and are similar for the two stimulus types. PSEs, estimated from probit analysis, were 1,565 and 1,536 Hz, respectively. However, when the same electric stimuli were compared to a range of acoustic sounds that was 0.86 octaves higher, the psychometric functions shifted markedly, as shown by the solid lines, and the PSEs increased to 2,164 and 2,516 Hz, respectively. Hence, in these conditions, the PSEs obtained depended strongly on the range of acoustic stimuli used. Where this occurred, it is hard to rule out the possibility that the subject largely ignored the electric stimuli, and simply judged each acoustic stimulus as “higher” whenever it was towards the top of the range of acoustic stimuli presented in that block of trials. An essential check is that psychometric functions are obtained with more than one range of acoustic stimuli, and that the results obtained with the two ranges are compared. Here, we adopt the arbitrary criterion that a match is reliable if the PSEs obtained with two different ranges differ by less than half the difference in the center frequencies of the two ranges. An example of a reliable measurement is shown in Figure 1B, for 12-pps pulse trains on electrode 1 for subject C1.

Part A shows psychometric functions obtained by subject B1 on electrode 6. Data obtained with a 25-pps pulse train in each ear and with a 1,031-pps pulse train vs. a pure tone are shown by circles and triangles, respectively. Psychometric functions measured using the lower and higher ranges of acoustic stimuli are shown by dotted and solid lines, respectively. Part B shows functions obtained for 12-pps pulse trains presented to subject C1’s electrode 1.

Interleaved adaptive tracks

The results obtained with this procedure also showed that some, but not all, matches were influenced by the experimenter’s choice of acoustic stimuli. An example comes from patient C1, for 12-pps pulse trains presented to electrode 3. When the initial frequencies for the lower and upper adaptive tracks were 350 and 1,400 Hz, respectively, they converged to 1,120 and 1,260 Hz. The PSE, estimated from the geometric mean of these two values, was 1,229 Hz. However, when these two values were shifted upwards by 0.86 octaves, the PSE increased substantially by 0.55 octaves to 1,805 Hz. In contrast, the same patient tested on electrode 1 showed only a 0.15-octave change in the PSE when the starting frequencies were shifted by 0.86 octaves. As in the previous subsection, we adopt the criterion of reliability that the PSE should not shift by more than half the shift in starting values.

Pitch matching by adjustment

Figure 2A shows pitch matches obtained on electrode 9 for patient B2, prior to activation of her microphone input. Matches were alternated between a 25-pps pulse train in each ear and between a 1,031-pps electric pulse train and a pure tone. The eight matches in each condition were obtained using a 1 octave range of starting frequencies centered on 2,160 Hz. The matches were 2,280 and 2,413 Hz, respectively, in the two conditions. However, further inspection of the data revealed that the match obtained on any one trial correlated strongly with the starting frequency used for that trial, as shown in Figure 2B; this correlation was 0.81 and 0.90 in the two conditions, respectively. Essentially, the subject could have obtained these data by ignoring the electric stimuli and simply adjusting the acoustic sound to a frequency close to that at the start of each run. Hence, one check for data obtained from pitch matches is that there should be no significant correlation between the starting frequency and final match across runs. Another requirement is that a sufficiently wide range of starting frequencies is used, and that the matches obtained converge onto a smaller range than that of the starting frequencies. In this article, we adopt the criterion that the standard deviation of the final matches should be significantly smaller (p < 0.05) than that of the initial starting frequencies.

A Average pitch adjustments, together with 95% confidence limits made by subject B2 for electrode 9. Results obtained with 25-pps pulse trains in each ear are shown by the open circle; those obtained with a pure tone and a 1,031-pps pulse train are shown by the filled triangle. The range of starting frequencies is shown by the vertical bar. Part B shows the correlation between final match and starting frequency for the data shown in part A. Part C shows a similar correlation obtained by subject C1 on electrode 10 with a 12-pps pulse train in each ear.

An example of a reliable match occurred when subject C1 matched a 12-pps acoustic pulse train to an electric pulse train of the same rate on electrode 10, the standard deviation of the matches was 0.24 octaves—substantially smaller than that of the starting frequencies—and the correlation between them was negative and non-significant (Fig. 2C).

Generalizability of non-sensory biases

The results described so far indicate that non-sensory biases can have a substantial effect on pitch matches obtained using a wide range of techniques. An important issue is whether such biases are specific to our patient population and/or to the choice of methods used here. This issue is addressed in the Appendix, where we show that biases occur for two other methods that have been used previously, and do so even in NH listeners when comparing qualitatively different sounds presented to different ears.

The remainder of the main part of this article concerns the matches that passed the reliability criteria described in the previous section. Such successful matches were obtained for subjects B1, C1, and C2. We focus on matches obtained with low-rate pulse trains in each ear. Complete data are provided in Tables 2, 3, and 4 for reference.

Changes over time and across methods

For subjects C1 and C2, there were instances where reliable matches were obtained for the same stimuli and electrodes at different stages of the experiment, and, sometimes, with different methods. Such instances are shown in the five panels of Fig. 3, with progressively later measures obtained for each subject and condition plotted further to the right of each panel; the different symbols refer to the different methods used, as shown by the legend in the bottom right of the figure. In three cases—electrode 1 for subject C1 and electrodes 8 and 10 for subject C2—the range of matches obtained is less than 0.2 octaves. In the case of subject C1 and electrode 1, this is quite remarkable given that the measures were obtained over a period of 15 months using three different measures. Indeed, the largest variation observed for any subject and electrode was 0.3 octaves, suggesting that the results obtained here were reasonably stable over time and across methods.

Changes in matched frequencies over time. The different methods are shown by different symbols, as illustrated by the key in the bottom right of the Figure. The abbreviations used for the different time points are as follows: Pre at the start of the tinnitus study, prior to any microphone or mp3 input; m after listening through mp3 player via auxiliary input, w washout period (speech processor removed), s speech mode (microphone activated). Post after all stages of the tinnitus study, and after some additional period of listening in “speech” mode (i.e., through the microphone input). "Post2", "Post3" and "Post4" refer to sessions run 3, 6, and 12 months after the end of the mp3 phase.

In the light of suggestions that everyday experience can influence electric-acoustic pitch matches, it is interesting to compare the matches obtained for each electrode with the frequencies to which that electrode was mapped in the subject’s clinical processor, in the period immediately prior to each measurement. For subject C1, the points labelled “S” were obtained after 3 months in speech mode, using a standard clinical map and where electrodes 1 and 10 were mapped to center frequencies of 432 and 2,134 Hz, respectively. The points labelled “SW” and “SWM” were obtained after the washout and “mp3” stages, respectively, during which times the patient did not hear any sounds simultaneously through both ears. The measures labelled “Post”, “Post3”, and “Post4” were obtained 3, 6, and 12 months after the end of the study, again using a clinical map. It can be seen that the matches on both electrodes were generally constant throughout this period, and were much higher than the patient experienced in everyday life. For patient C2, the only instance where she had listened to sounds simultaneously through the two ears was at time “MWS” for electrode 4. At this point, she had been listening for 3 months using an experimental map in which electrode 4 was mapped to 1,285 Hz. This was lower than the matches obtained, and, if anything, the matches had shifted up after exposure to the speech mode of the study. We therefore conclude that the matches obtained here were not strongly affected by experience. This is fortunate because the primary aim of this study is to compare the place of excitation produced by acoustic and electric stimuli, unconfounded by the listener acclimatizing to any mismatch. We should stress, however, that this does not mean that acclimatization would not occur in patients without normal hearing in the unimplanted ear.

Effects of level on the matches obtained

The 12 and 25-pps pulse trains used here were presented at a higher level per pulse than would normally occur in a cochlear implant speech-processing strategy using higher pulse rates. It is therefore interesting to observe whether the matches obtained here strongly depended on signal level. Matches were therefore obtained for subject C1 at the original level and with the acoustic 12-pps pulse trains attenuated by 25 dB, using the method of constant stimuli, for electrodes 1 and 10. When the 12-pps electric stimuli were re-balanced to these lower levels, the current levels were reduced from −8.5 to −9.9 dB and from −4.8 to −6.2 dB re 1 mA, respectively. These measures were obtained approximately 6 months after the end of the tinnitus treatment trial, during which time the subject had been listening through her implant in “speech” mode on a daily basis. For electrode 1, the matches were very similar (1,029 and 1,071 Hz). This was also true for electrode 10 (4,437 vs. 4,579 Hz), although in this case the measures obtained at the quieter level failed to pass our check for range effects. We therefore conclude that there is no evidence for strong effects of stimulus level on the matches obtained.

Comparison of reliable results to predictions based on cochlear place

The three panels of Figure 4 show the data of the three subjects—B1, C1, and C2—for whom reliable matches were obtained for one or more electrodes. Those matches are plotted using a solid square when based on the geometric mean of more than one reliable match, and by an open symbol when based on a single measure, with the shape of the symbol indicating the particular method used.

The dashed line in each panel shows the predicted (center) frequency corresponding to each electrode for a given subject, according the formula proposed by Greenwood (1990). Dotted lines show ±0.5 octaves re this prediction. The solid line shows the predictions of the Leiden model. For subject C2, the thick gray line shows predictions based on Greenwood’s formula for the first of the two scans obtained (see text for details), with the other lines showing predictions based on the second scan. Insertion angles, using the reference point described in the Methods section, are shown on the top of each plot. Where more than one reliable match was obtained for a given electrode, the geometric mean is shown by a solid square; in this case, the error bars show the 95% confidence limits estimated from the PSEs obtained with the individual measures. Where only one reliable match was obtained, the PSE is shown by an open symbol, with the shape of the symbol reflecting the method used (see key). In this case, and for the constant-stimuli and interleaved adaptive procedures, the error bars span the distance from the PSE obtained with the lower range to that obtained with the higher range. For the pitch-matching procedure, it spans the 95% confidence limits around the average match. Where error bars are not visible they are smaller than the symbols.

The dashed and solid lines in Figure 4 show the predicted frequency-to-place functions derived from Greenwood’s formula and the Leiden model, respectively. The dotted lines show frequencies that are half an octave above and below the Greenwood function. It can be seen that the two curves are quite similar, the most consistent difference being a tendency for the Leiden model to predict slightly lower frequencies, at least for the more apical electrodes. For subject C1, two scans were obtained. The first was obtained shortly after implantation and before switch-on, and is shown by the thick gray line. The second was obtained 12 months after the end of the tinnitus study, and is shown by the dashed and solid black lines. It can be seen that these two curves differ substantially, due to the electrode array having slipped. Indeed, the reason for performing the second CT scan was that the pitch matches fell above the predictions based on the initial scan, and because we could not think of a reason for this discrepancy. We choose to compare the matches to the results of the second scan, for the following reasons (a) matches on electrodes 1 and 10, obtained at time “Post4” (Fig. 3), were consistent with those obtained previously throughout the study, and were obtained on the same day as the second scan, and (b) an analysis of the routine clinical measurements obtained with subject C2 revealed an increase in impedance for electrode 16 three months before the end of the speech phase—i.e., 3 months before the earliest measurements in Figure 3 for that subject. This was accompanied by an increase in threshold levels for electrodes 15 and 16 relative to the other electrodes, and is consistent with the results of the second scan showing that electrode 16 was close to the edge of the cochleaFootnote 2.

For all subjects, the matches generally fall within half an octave of the Greenwood and Leiden predictions. Importantly, there is no evidence of the trend, reported by Boëx et al. (2006) and by Dorman et al. (2007), for matches to fall between 1 and 2 octaves below the predictions of Greenwood’s model. Indeed, the fact that a deviation from those predictions prompted a second scan for subject C1, and that the results then matched that prediction, is further evidence both for the reliability of our matches and for the validity of the Greenwood and Leiden fits.

General Discussion

Problems in comparing between two ears

We have reported several instances where the pitch matches obtained between the two ears are strongly influenced by non-sensory biases. The fact that such biases can occur not only for implant patients but also (as shown in the Appendix) in NH listeners suggest that this is not likely to be specific to the particular CI users or to the stimuli used in experiment 1. Instead, we argue that non-sensory factors are likely to prove a ubiquitous problem when interpreting studies that require subjects to judge the pitches of stimuli that are likely to differ on other perceptual dimensions.

Although our study is the first to check formally for range biases, it is likely that non-sensory factors of some sort influenced the results of other studies. For example, Vermeire et al (2008) plotted not only the average matches between acoustic and electric stimuli, obtained using their magnitude estimation method, but also the results of individual matches. These could, strikingly, vary by several octaves for a given electrode and subject. This sizeable variation could simply arise from stimulation of an electrode yielding an ill-defined pitch. Alternatively, or additionally, pitch estimates for a given stimulus could be influenced by the stimuli presented shortly before it (“sequential bias”: Poulton 1979); as stimuli were presented in a random order, the stimuli presented immediately before any given pure tone or pulse train would vary from block to block. This issue is addressed further in the Appendix. Substantial variability, of up to an octave, was also observed across and within sessions by Reiss et al (2007).

It is also possible that the range biases observed here may have introduced a systematic bias in previous estimates of pitch matches between electric and acoustic stimuli. When the patient has residual hearing only at low frequencies, one is obliged to present acoustic stimuli in that restricted audible range. Because the range of acoustic stimuli can affect the match obtained, this factor may partly or wholly be responsible for the observation that, with such patients, the obtained matches often fall below those predicted by Greenwood’s (1990) function (Blamey et al. 1996; Boëx et al. 2006; Dorman et al. 2007). An exception to this finding was reported by McDermott et al (2009), who found matches close to those predicted by a cochlear model in five patients who, as in the present study, had not worn their CI in everyday life prior to testing. Those matches were also higher than obtained from subjects who had worn their device for some time, a finding tentatively attributed to acclimatization effects. Indeed, McDermott et al’ s results are consistent with our findings that the matches obtained with recently-implanted patients match the predictions of Greenwood’s model. However, as with all previous studies, we would recommend caution when interpreting results obtained in the absence of checks for non-sensory biases.

Effect of stimulus type and experimental methods on reliability of matches

Stimulus type

In a few cases, we were able to use the same method for a given electrode and subject, using more than one type of stimulus. There is some evidence that, at least for the 12-pps stimuli, matches were more reliable than for 1,031-pps pulse trains vs. pure tones. Pitch matches obtained with subject C1 on electrodes 1 and 10 (Table 2) showed a smaller correlation between starting and matched frequencies for 12-pps pulse trains than for 1,031-pps/pure tones. The same subject also showed slightly smaller range effects using the interleaved adaptive procedure for 12-pps than for 1,031-pps/pure tone stimuli, although in this case the difference was small. Finally, subject C2 showed a large difference in the same direction using interleaved adaptive procedures and electrode 8 (Table 4). We should note, however, that these two stimuli were directly compared for only a few subjects and electrodes, and so our conclusions as to the overall superiority of the 12-pps stimuli remain tentative. It is, however, certainly the case that one can reduce bias for a given condition and electrode by switching to a different stimulus type, and that we have never encountered a situation where the 12-pps stimuli produce larger range effects than another stimulus.

Experimental method

In previous articles, the first author has observed that, when comparing two electrical stimuli, it is easier to obtain reliable matches using the method of constant stimuli than allowing the subject to adjust one stimulus in order to obtain a match (Carlyon et al. 2002). This is probably because, at the end of a pitch-adjustment procedure, the stimuli should have very similar pitches, but may differ in some other perceptual dimension. This can make it hard for the inexperienced listener to focus on pitch. In contrast, with the method of constant stimuli, pitch varies over quite a wide range from presentation to presentation, perhaps encouraging the subject to focus on that dimension. Similarly, our interleaved adaptive procedures converge on the 71% and 29% points of the psychometric function, so that, even at the end of the procedure, acoustic sounds with quite different pitches are presented. We therefore prefer the latter two methods to the former on theoretical grounds. However, we should stress that we did not systematically compare the effectiveness of the different methods, but rather tried different methods in an attempt to reduce range biases and to obtain meaningful data. Although there are more “unacceptable” matches obtained using adjustment than for the other procedures (compare Table 2 to Tables 3 and 4), this could well be due to differences in the subjects tested and stimuli used rather than to the procedures themselves.

Variation across electrodes

The reliability of the matches obtained could differ substantially across electrodes, even for the same subject and stimulus type. One example comes from patient B1, when adjusting the pitch of a pure tone to that of a 1,031-pps electric pulse train: the correlation between starting frequency and final match was only −0.03 for electrode 9 but 0.86 for electrode 6. Perhaps more strikingly, although subject C1 reliably obtained consistent matches for 12-pps pulse trains on electrode 1, using a variety of procedures (Fig. 3), an attempt to obtain matches on electrode 6, using the method of constant stimuli, resulted in substantial range effects (Table 3). At present, we do not know why some electrodes produce more reliable matches than others, although differences in the pattern of neural survival are one obvious possibility.

Summary

-

1.

We have reported pitch comparison data from four patients having normal hearing in one ear and a CI in the other. Three different techniques were used: pitch adjustment, constant stimuli, and interleaved adaptive procedures.

-

2.

By introducing a number of checks, we showed that all three techniques are subject to non-sensory biases, and argued that such biases may have influenced the results of previous findings. In the Appendix we show that similar biases occur even for NH listeners and for other widely used procedures.

-

3.

It is nevertheless possible to obtain reliable electric-acoustic matches that are relatively free from range biases, for a subset of CI subjects and conditions. Those matches do not deviate consistently from the predictions of Greenwood’s (1990) function and of a cochlear model.

Notes

We initially used a pulse rate of 25 pps because we expected this rate to be slow enough to produce a pulsatile percept, and because this prediction was confirmed by a unilaterally deaf CI patient with whom we performed some pilot testing, and whose data are not presented here. However, subject C1 reported that the 25 pps pulse rate sounded fairly continuous and so we reduced the rate to 12 pps for her and for subsequently tested patients. The lower rate did indeed sound pulsatile for all subjects and electrodes.

The possibility that the electrode array may have slipped was suggested by Prof. Hugh McDermott. Another interesting point is that a pitch adjustment to a 1,031-pps pulse train on electrode 3, made at the start of the tinnitus study (time “pre”, Table 2)—close to the time of the first CT scan and prior to the elevation in thresholds and impedance for electrode 16—was 804 Hz. This was close to the prediction of 771 Hz based on that first scan.

It is improbable that a similar slip could have occurred for subject C2 because her electrodes 15 and 16 were already close to the edge of the cochlea, and so any further slip would have been noticed from a change in thresholds and impedances for those and neighboring electrodes.

References

Blamey PJ, Dooley GJ, Parisi ES, Clark GM (1996) Pitch comparisons of acoustically and electrically evoked auditory sensations. Hear Res 99:139–150

Boëx C, Baud L, Cosendai G, Sigrist A, Kós M-I, Pelizzone M (2006) Acoustic to electric pitch comparisons in cochlear implant subjects with residual hearing. JARO 7:110–124

Briaire JJ, Frijns JHM (2005) Unraveling the electrically evoked compound action potential. Hear Res 205:143–156

Briaire JJ, Frijns JHM (2006) The consequences of neural degeneration regarding optimal cochlear implant position in scala tympani: a model approach. Hear Res 214:17–27

Burns EM, Viemeister NF (1981) Played again SAM: Further observations on the pitch of amplitude-modulated noise. J Acoust Soc Am 70:1655–1660

Carlyon RP (1997) The effects of two temporal cues on pitch judgements. J Acoust Soc Am 102:1097–1105

Carlyon RP, van Wieringen A, Long CJ, Deeks JM, Wouters J (2002) Temporal pitch mechanisms in acoustic and electric hearing. J Acoust Soc Am 112:621–633

Dauman R, Baguley D, Carlyon RP et al (2009) The Bordeaux-Cambridge Programme for unilateral sudden deafness with disabling tinnitus. Assoc Res Otolaryngol Abs 32:154

Dorman MF, Spahr T, Gifford R, Loiselle L, McKarns S, Holden T, Skinner M, Finley C (2007) An electric frequency-to-place map for a cochlear implant patient with hearing in the nonimplanted ear. Jaro J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 8:234–240

Frijns JHM, Briaire JJ, Grote JJ (2001) The importance of human cochlear anatomy for the results of modiolus-hugging multichannel cochlear implants. Otol Neurotol 22:340–349

Greenwood DD (1990) A cochlear frequency-position function for several species - 29 years later. J Acoust Soc Am 87:2592–2605

Hartmann WM, McAdams S, Smith BK (1990) Hearing a mistuned harmonic in an otherwise periodic complex tone. J Acoust Soc Am 88:1712–1724

Jesteadt W (1980) An adaptive procedure for subjective judgements. Percept Psychophys 28:85–88

Krumbholz K, Patterson RD, Pressnitzer D (2000) The lower limit of pitch as determined by rate discrimination. J Acoust Soc Am 108:1170–1180

Laneau J, Boets B, Moonen M, van Wieringen A, Wouters J (2005) A flexible auditory research platform using acoustic or electric stimuli for adults and young children. J Neurosci Meth 142:131–136

Liberman MC (1984) Single-neuron labeling and chronic cochlear pathology. I. Threshold shift and characteristic-frequency shift. Hear Res 16:33–41

Long CJ, Nimmo-Smith I, Baguley DM, O'Driscoll M, Ramsden R, Otto SR, Axon PR, Carlyon RP (2005) Optimizing the clinical fit of auditory brain stem implants. Ear Hear 26:251–262

McDermott HJ, Sucher C, Simpson A (2009) Electro-Acoustic stimulation: acoustic and electric pitch comparisons. Audiol Neurotol 14(suppl 1):2–7

McDermott HJ, Sucher CM (2006) Perceptual dissimilarities among acoustic stimuli and ipsilateral electric stimuli. Hear Res 218:81–88

McFadden D (1986) The curious half octave shift: evidence for a basalward migration of the travelling-wave envelope with increasing intensity. In: Salvi RJ, Henderson D, Hamernik RP, Colletti V (eds) Basic and applied aspects of noise-induced hearing loss. Plenum, New York

McKay CM, McDermott HJ, Carlyon RP (2000) Place and temporal cues in pitch perception: are they truly independent? Acoustics Research Letters Online, http://scitationaiporg/arlo/ 1: 25-30. Last viewed 14 October 2009

Meddis R, Hewitt M (1991) Virtual pitch and phase sensitivity studied using a computer model of the auditory periphery: pitch identification. J Acoust Soc Am 89:2866–2882

Micheyl C, Moore BCJ, Carlyon RP (1998) The role of excitation-pattern cues and temporal cues in the frequency and modulation-rate discrimination of amplitude-modulated tones. J Acoust Soc Am 104:1039–1050

Moore BCJ (1973) Frequency difference limens for short-duration tones. J Acoust Soc Am 54:610–619

Moore BCJ, Glasberg BR (1996) A revision of Zwicker's loudness model. Acustica United with Acta Acustica 82:335–345

Patterson RD (1987) A pulse ribbon model of monaural phase perception. J Acoust Soc Am 82:1560–1586

Pijl S, Schwarz DWF (1995) Melody recognition and musical interval perception by deaf subjects stimulated with electrical pulse trains through single cochlear Implant electrodes. J Acoust Soc Am 98:886–895

Poulton EC (1979) Models for the biases in judging sensory magnitude. Psychol Bull 86:777–803

Reiss LAJ, Turner CW, Erenberg SR, Gantz BJ (2007) Changes in pitch with a cochlear implant over time. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 8:241–257

Shackleton TM, Carlyon RP (1994) The role of resolved and unresolved harmonics in pitch perception and frequency modulation discrimination. J Acoust Soc Am 95:3529–3540

Shannon RV (1983) Multichannel electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve in man. I. Basic psychophysics. Hear Res 11:157–189

Stakhovskaya O, Sridhar D, Bonham BH, Leake PA (2007) Frequency map for the human cochlear spiral ganglion: Implications for cochlear implants. Jaro J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 8:220–233

Townshend B, Cotter N, van Compernolle D, White RL (1987) Pitch perception by cochlear implant subjects. J Acoust Soc Am 82:106–115

Verbist BM, Frijns JHM, Geleijns J, van Buchem MA (2005) Multisection CT as a valuable tool in the postoperative assessment of cochlear implant patients. Am J Neuroradiol 26:424–429

Verbist B M, Joemai R M S, Briaire J J, Teeuwisse W M, Veldkamp W J H, Frijns J H M (2010) Cochlear coordinates in regard to cochlear implantation: a clinically individually applicable 3 dimensional CT-based method. Otology & Neurotology (in press)

Verbist BM, Joemai RMS, Teeuwisse WM, Veldkamp WJ, Geleijns J, Frijns JHM (2008) Evaluation of 4 multisection CT systems in postoperative imaging of a cochlear implant: a human cadaver and phantom study. Am J Neuroradiol 29:1382–1388

Vermeire K, Nobbe A, Schleich P, Nopp P, Voormolen MH, Van de Heyning PH (2008) Neural tonotopy in cochlear implants: an evaluation in unilateral cochlear implant patients with unilateral deafness and tinnitus. Hear Res 245:98–106

Zeng F-G (2002) Temporal pitch in electric hearing. Hear Res 174:101–106

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Fan-Gang Zeng and Jeff Carroll for their advice and co-operation during pilot testing of a patient implanted in the United States. Author OM was supported by Wellcome Trust grant number 080216. Helpful comments on a previous version of this MS were provided by Colette McKay, Hugh McDermott, John Middlebrookes, and two anonymous reviewers. Financial support for this study was provided by Advanced Bionics Ltd. We thank our subjects for their good-natured perseverance.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Simulations with NH subjects

Appendix: Simulations with NH subjects

Rationale

Experiment 1 showed that electro-acoustic matches were subject to non-sensory biases. It is important to know whether such biases were specific to our subjects—who, for example, had tinnitus that might have rendered pitch matches more difficult—or to the specific procedures used. This additional experiment therefore studied the effect of one non-sensory bias—the “range” bias—in NH subjects, using two procedures:

-

1.

The magnitude estimation procedure has been used in two studies involving electric-acoustic pitch comparisons (Vermeire et al. 2008; McDermott et al. 2009), including the only one to test patients with normal hearing in the unimplanted ear. Subjects assign numbers to the pitches of acoustic and electric stimuli, with electric and acoustic stimuli that are assigned the same number being deemed to have the same pitch.

-

2.

The “Midpoint Comparison Procedure” (Long et al. 2005) procedure requires the subject to make comparisons betweens pairs of stimuli, and places the entire stimulus set in a ranked order. As with magnitude estimation, it does not involve subjects comparing an arbitrary range of acoustic stimuli to a single electrode, but, by using forced-choice comparisons, overcomes some of the biases inherent in the assignment of numbers to sensations.

Method

Stimuli consisted of pure tones and one third octave-band noises, generated digitally at a sampling rate of 44 100 Hz, played out of a VideoLogic Sonic Fury sound card attached to a computer and attenuated (Tucker-Davis Technologies, Model PA4). Noise bands were generated by summing a large number of harmonics (1-Hz spacing) in random phase. The stimulus duration was always 500 ms, including 20-ms linear ramps. The levels of the tones were determined as in experiment 1, using the loudness model of Moore and Glasberg (1996), and the levels of the noises were adjusted to have the same RMS as that of the tones for a given frequency. The sound pressure level at 1,000 Hz was 60 dB SPL. The tones were always presented to the left ear and the noises were presented to the right ear. Six normal-hearing subjects listened individually in a double-walled sound-insulating room through a Sennheiser HD650 headset.

Magnitude estimation

Each subject was tested on two conditions, on three separate days, using an ABA design, with the condition that was performed twice split equally between the six subjects. In both conditions, each block consisted of eight tones and eight noises presented in random order, five times each, giving a total of 80 presentations. The eight tones had frequencies that were logarithmically spaced between 375 and 3,000 Hz. After each presentation the subject was required to assign a number, of between zero and 100, to the pitch. At least eight such blocks were run in each session, yielding at least 40 estimates per sound. The conditions differed in whether the center frequencies of the noise bands ranged from 125-1,000 Hz (“range 1”) or from 1,000-8,000 Hz (“range 2”). As in previous studies (Vermeire et al. 2008; McDermott et al. 2009), two stimuli that were assigned the same number were deemed to have the same matched pitch. Prior to this stage of the experiment, all stimuli were presented four times (in ascending and descending order) so as to give the subject an idea of the range of pitches that s/he would hear. Subjects were also encouraged to use the whole range of numbers in every session.

Midpoint comparison procedure

In this part of the experiment, the same subjects were tested on two additional sessions. The magnitude estimation task was replaced with the midpoint comparison procedure, which has been described in detail elsewhere (Long et al. 2005). Briefly, it consists of a series of forced—choice judgements between pairs of sounds, with the decision as to which two sounds to compare on each trial being driven by the results of previous trials, using an algorithm that arrives at a rank order for the whole set using as few comparisons as possible. Typically, 16 sounds can be rank-ordered using only about 40 comparisons. However, because subjects sometimes make errors, we repeated each procedure 25 times, allowing us to derive a mean and standard error for each rank.

Results

The plots to the left of Figure 5A shows the magnitude estimation results obtained in the first two sessions for one representative subject. Data obtained when the noises were in range 1 are shown on the top and those for range 2 are shown on the bottom; recall that the order in which these datasets were obtained differed across subjects. Recall also that, although data are shown separately for noises (open symbols) and tones (filled symbols), these two types of stimulus were always mixed within each block

Part A shows results obtained from the first two sessions for two of the normal-hearing subject participating in the magnitude-estimation experiment. Functions are shown separately for tones and noises, even though they were always mixed within each block. The top and bottom rows show data obtained with the noises in the lower and upper ranges, respectively. The filled symbols in part B show the estimated frequency for each tone, corresponding to a noise centered on 1,000 Hz, when the noises were in the upper range, versus the estimated frequency when the noise was in the lower range. Data are shown for all subjects, using different symbols for each one; the open symbols show the same comparison for the midpoint comparison procedure. Part C shows the frequency of a pure tone assigned the same number as the 1,000-Hz noise in sessions 1 (abscissa) and 3 (ordinate), during which the noise center frequencies were in the same range.

It is clear that the results obtained depended on the range used for the noises. When the noises were in range 1 (top graphs), the curve for the noises (open symbols) falls to the left of that for the tones (filled symbols). In other words, when a tone and a noise are assigned the same number, the noise usually has a lower frequency than the tone. However, just the opposite finding occurs when the noises are in range 2. In other words, a range bias is observed using this procedure, consistent with subjects scaling the two types of sound independently. These data also show evidence for the centering bias (Poulton 1979), in which subjects use the entire range of numbers available; this caused subject S2 to assign a lower number to the lowest-frequency tone when presented in the context of “Range 2” noises—in which case it was the lowest-frequency stimulus in the block—than when presented with “Range 1” noises. Evidence for the contraction bias (Poulton 1979), whereby numbers close to 50 are assigned for all stimuli, is shown by the data for another subject, shown to the right of Figure 5A.

To illustrate the size of the range bias for each subject, we obtained, from the magnitude estimation functions, the pure-tone frequency that was judged to have the same numerical pitch value as the 1,000-Hz noise, both when that noise was presented as part of range 1 and when it was presented as part of range 2. (The 1,000-Hz noise was the only one that was included in both ranges). These data were then plotted using solid symbols in Figure 5B, with the “range 1” matches on the abscissa and the corresponding “range 2” matches on the ordinate. The solid diagonal line shows the prediction for no bias, and the dashed lines show the predictions for biases of 1 and 2 octaves. It can be seen that the bias ranges in size from about 0.25 to about 2 octaves, across subjects.

The range biases obtained by the MPC procedure are shown for each subject by the open symbols in Figure 5B. These biases are generally similar to those obtained with the magnitude estimation procedure. One difference (not shown in the summary data) is that no contraction or centering bias could occur, because the procedure involved forced-choice comparisons rather than number assignment. Part c shows that, although subjects showed different range effects, the matches obtained in the first and third sessions of the magnitude-estimation experiment (which used the same ranges) were consistent. This is important, because it suggests that the repeatability of a measurement is no guarantee that it is free from non-sensory biases.

Overall, our results show that the magnitude estimation and MPC procedures show range biases of about the same magnitude. We have also obtained measurements with four NH subjects, similar to those obtained here, but using the method of constant stimuli, and have also observed substantial biases. The main difference between the procedures appears to be that magnitude estimation is prone to additional biases—such as the contraction and centering biases—that are specific to subjects’ use of numbers, and which do not occur for the MPC procedure or for the method of constant stimuli.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Carlyon, R.P., Macherey, O., Frijns, J.H.M. et al. Pitch Comparisons between Electrical Stimulation of a Cochlear Implant and Acoustic Stimuli Presented to a Normal-hearing Contralateral Ear. JARO 11, 625–640 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10162-010-0222-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10162-010-0222-7