Abstract

Studies of Marenzelleria species were often hampered by identification uncertainties when using morphological characters only. A newly developed PCR/RFLP protocol allows a more efficient discrimination of the three species Marenzelleria viridis, Marenzelleria neglecta and Marenzelleria arctia currently known for the Baltic Sea. The protocol is based on PCR amplification of two mitochondrial DNA gene segments (16S, COI) followed by digestion with restriction enzymes. As it is faster and cheaper than PCR/sequencing protocols used so far, the protocol is recommended for large-scale analyses. The markers allow an undoubted determination of species irrespective of life stage or condition of the worms in the samples. The protocol was validated on about 950 specimens sampled at more than 30 sites of the Baltic and the North Sea, and on specimens from populations of the North American east coast. Besides this test we used mitochondrial DNA sequences (16S, COI, Cytb) and starch gel electrophoresis to further investigate the distribution of the three Marenzelleria species in the Baltic Sea. The results show that M. viridis (formerly genetic type I or M. cf. wireni) occurred in the Öresund area, in the south western as well as in the eastern Baltic Sea, where it is found sympatric with M. neglecta. Allozyme electrophoresis indicated an introduction by range expansion from the North Sea. The second species, M. arctia, was only found in the northern Baltic Sea, where it sometimes occurred sympatric with M. neglecta or M. viridis. For Baltic M. arctia, the most probable way of introduction is by ship ballast water from the European Arctic. There is an urgent need for a new genetic analysis of all Marenzelleria populations of the Baltic Sea to unravel the current distribution of the three species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Baltic Sea, with a total area of ∼382,000 km2, is one of the largest brackish water regions in the world and exists in its present form for only a few thousand years. A horizontal and vertical salinity gradient is the most important factor characterizing this sea area. Salinity in surface water varies from 20 to 24 ppt in the western Baltic Sea to 2–3 ppt in the innermost parts of the Gulfs of Finland and Bothnia in north. In depth of 50–70 m a halocline exists, which separates the surface layer from a deep water body with higher salinity and irregular occurrence of hypoxia and anoxia. Both the inflow of saline North Sea water via the Kattegat and the Belt Sea and the fresh water input affect the salinity regime (e.g. Kullenberg and Jacobsen 1981; Matthäus and Nausch 2003). For a long time the Baltic Sea has been a recipient area for introduced non-indigenous estuarine and marine organisms, and over 100 non-native species have been recorded in the area (Leppäkoski et al. 2002). Among them is the shipworm, Teredo navalis (Bivalvia; Leppäkoski et al. 2002), which has enormous economic impacts in the southern Baltic. Many non-native species, for example Mya arenaria (Bivalvia) and Balanus improvisus (Cirripedia; Leppäkoski 1984; Jansson 1994) originate from the Western Atlantic and are common species along the coasts of the Baltic Sea today. The Ponto-Caspian area as well is an important donor region for invasive species. Twenty-two species (e.g. the zebra mussel Dreissena polymorpha and the cladoceran Cercopagis pengoi) have been recorded to derive from there (Baltic Sea Alien Species Database 2001; Ojaveer et al. 2002). The number of invasive species seems to increase which is a direct result of intensified and accelerated human trade and travel. On the other hand this reflects also the increasing interest and awareness to the problem of biological invasions. Dominant vectors facilitating species invasions into new areas are man-made waterways, shipping, including transport of ballast water and hull fouling, and aquaculture. Among all, the transport of ballast water by ocean-going ships is the most important introduction vector. Up to 4,000 species are transported in ship ballast water between continents every day (e.g. Carlton and Geller 1993; Gollasch et al. 1998).

In the year 1985, a new polychaete species was found in the Baltic Sea and first identified as Marenzelleria viridis (Bick and Burckhardt 1989). It was assumed that the species that had been found for the first time in the North Sea a few years ago (1979, Forth estuary; Elliott and Kingston 1987), had now invaded the Baltic Sea. However, genetic analyses revealed that the species found in the North Sea and the species, which had invaded the Baltic Sea, were sibling species of the same genus (Bastrop et al. 1995, 1997, 1998; Röhner et al. 1996a, b). The species found in the North Sea was first named genetic type I and later M. cf. wireni, that one in the Baltic Sea genetic type II and later M. cf. viridis (Bastrop et al. 1997; Bick and Zettler 1997). After a morphological revision of the genus Marenzelleria, Sikorski and Bick (2004) described Marenzelleria neglecta Sikorski & Bick, 2004 (formerly M. genetic type II, M. cf. viridis) as a new species, and M. viridis (Verrill, 1873) (formerly M. genetic type I, M. cf. wireni) is now the valid name for the species found in the North Sea. Another three species of the genus are known: M. wireni Augener, 1913 and Marenzelleria arctia (Chamberlin, 1920) occur in the Arctic and have not been recorded elsewhere till today. M. bastropi Bick, 2005 (formerly M. genetic type III) was found by genetic analysis of material from the Currituck Sound (NC, USA; Röhner et al. 1996b; Bastrop et al. 1997, 1998) and then taxonomically described by Bick (2005). The denomination of species in the present study follows strictly Sikorski and Bick (2004) and Bick (2005).

Genetic studies revealed high genetic similarity of conspecific North American populations and populations in the North Sea (M. viridis) and in the Baltic Sea (M. neglecta; Röhner et al. 1996a, b; Bastrop et al. 1998), respectively. Because the species develop via pelagic larvae, the most probable way of introduction was by ship ballast water (Essink and Kleef 1993) from North America to the North Sea and, in a second separate introduction event, into the Baltic Sea (Bastrop et al. 1997).

Since their introduction, the respective species have been spreading rapidly along the coasts and estuaries of the North and the Baltic Seas and have become major faunal elements wherever they settled (Essink and Kleef 1993; Zettler 1996). After the first appearance in the Baltic Sea in the Darss-Zingst Bodden Chain (Germany; Bick and Burckhardt 1989), Marenzelleria was observed in the following years in Swedish (Persson 1990), Polish (Gruszka 1991), Lithuanian, Latvian and Estonian waters (Olenin and Chubarova 1992; Lagzdins and Pallo 1994; Zmudzinski et al. 1997; Kotta and Kotta 1998). It further spread northwards to the Finnish coastal waters (Stigzelius et al. 1997) and far into the Bothnian Bay (Leonardsson 2001). By now, Marenzelleria spp. have successfully invaded the entire Baltic Sea.

There are often three phases, which are typical of the population development in newly invaded areas: an initial, strong increase in abundance, a stabilization period, and a phase of decrease. This pattern has been observed also for Marenzelleria in the Wadden Sea (Essink and Dekker 2002). A maximum abundance of up to 28,000 individuals per m2 was found in German estuaries (Kube et al. 1996). In the Baltic Sea Marenzelleria spp. have been reported to occur mostly in shallow areas between 0.2 and 30 m, but have also been found up to 90 m depth (Lagzdins and Pallo 1994; Kube et al. 1996). Recently, Marenzelleria has been found in high densities in depths up to 286 m in the Åland Sea (unpublished data of the Finnish Institute of Marine Research).

It was assumed that M. viridis colonizes exclusively the estuaries and coastal waters of the North Sea, whereas M. neglecta is found, besides the oligohaline parts of the Elbe river estuary, only in the Baltic Sea (Bastrop et al. 1995, 1997, 1998; Röhner et al. 1996a, b; Bick and Zettler 1997; Blank et al. 2004). However, in autumn 2004, first evidence arose that M. viridis has invaded the Baltic Sea. Subsequently, we started to re-analyse some Marenzelleria populations of the western, central and northern parts of the Baltic Sea. In a preliminary survey we analysed worms from four sampling sites by sequencing of three mitochondrial gene segments (Bastrop and Blank 2006). We could prove three species of the genus Marenzelleria in the Baltic Sea: M. neglecta, M. viridis and M. arctia. All species could be discriminated beyond doubt using these markers. M. viridis was found in the western Baltic Sea (Isle of Langenwerder, Mecklenburg Bight, Germany) as well as in the Gulf of Bothnia (Sweden), where it occurs sympatric with M. arctia. Around the Isle of Askö (Sweden) M. arctia could also be detected sympatric to M. neglecta in ∼30 m water depth. For M. arctia these are the first records outside the Arctic.

These new findings underline the urgency for an undoubted species discrimination. As shown above, species identification using morphological characters only, was difficult from the beginning. Even a morphological revision of the genus including all five known species could not remove these problems (Sikorski and Bick 2004; Bick 2005). Sikorski and Bick (2004) stated that: (1) (p. 264) M. viridis is particularly difficult to distinguish from M. neglecta, and (2) (p. 271) Marenzelleria arctia strongly resembles M. neglecta, especially in the case of juveniles. “...To avoid probable misidentification of the pair M. arctia–M. neglecta …, the differentiation of these species in samples containing only small…unpigmented…specimens…is not recommended”.

Identification still completely fails for larvae, juveniles and incomplete specimens, which predominate in all samples. High confusion also exists in the correct use of species names. A database search in ASFA, SCOPUS, Web of Science® and Zoological Record covering the years 1999–2005 yielded altogether 41 citations, which are concerned with the invasion of Marenzelleria spp. in Europe. In 24 papers (∼58%) incorrect species denomination [M. viridis instead of M. cf. viridis, M. neglecta or M. (genetic) type II] for the Baltic Sea species was used.

In all these cases genetic analyses are suitable tools that help to avoid misidentification and allow species identification beyond doubt. Correct species assignment is a fundamental requirement for all ecological and physiological studies on Marenzelleria species. In the eastern Baltic Sea, which is an area of intensive research on Marenzelleria invasion biology, the detection of M. arctia and M. viridis is an impressive example for the urgent need of a correct species identification (Bastrop and Blank 2006).

The aim of the present study was (1) to develop and validate a molecular species determination key which might replace the uncertain species identification by morphological characters, and (2) to analyse more specimens and populations in the Baltic Sea to produce a better picture of the current distribution of the three species occurring in the Baltic Sea. To realize these aims we used three genetic methods: RFLP/PCR technique was used to screen more than 30 sampling sites in the Baltic Sea and North Sea and these results were randomly validated by PCR/Sequencing. Sequencing and starch gel electrophoresis of allozymes were used to obtain additional information about the potential populations of origin of the Baltic Sea M. arctia and M. viridis populations as well as to detect hybridization between M. viridis and M. neglecta.

Materials and methods

In addition to the seven sampling sites studied by Bastrop and Blank (2006) we investigated another 16 sites and included five sites already studied by Röhner et al. (1996a, b) and Blank et al. (2004). Compared to Bastrop and Blank (2006) the number of specimens at most sampling sites was increased and allozyme data of four sampling sites were added.

Sampling

Samples were collected at the sites shown in Fig. 1. In Table 1, the characteristics of the sampling sites and the number of specimens analysed are listed. Specimens were not determined taxonomically before DNA extraction. After genetic analyses A. Bick verified species affiliation of some individuals by taxonomy. Samples were either frozen in liquid nitrogen or at −80°C (for starch gel electrophoresis) or fixed in at least 80% ethanol (for DNA investigations) until further investigations.

Marenzelleria spp. Map of the Baltic Sea and the eastern North Sea showing the sampling locations. Ems estuary (EM); Elbe river estuary (E); Ringkøbing Fjord (RK); Barsebäck (BB); Öresund (ÖS, includes four sampling sites); Isle of Langenwerder (LW); Warnemünde (W); Warnow-Breitling (B); Darss-Zingst Bodden Chain (D); Isle of Rügen (RG); Pomeranian Bight (OB, includes 19 sampling sites); Peene Estuary (PE); Isle of Askö, 30 m depth (AK); Isle of Askö, 20 m depth (IA); Isle of Askö, shallow water (BA); Sandviken (SV); Himmerfjärden (HJ); Åland Sea (AS); Åland Sea (AE); Söderhamn (SÖ); Bothnian Sea (BS); Bothnian Sea (BE); Tvärminne (TV); Gulf of Finland (GF); Puck Bay (PU); Vistula Lagoon (FH); Pärnu (PÄ); Gulf of Riga (GR); Riga (RI); Klaipeda (KL). Asterisks denote samples from earlier sampling dates (Table 1), indicating M. neglecta populations. Dots denote the different species M. viridis (white), M. neglecta (grey) and M. arctia (black). Sympatric sampling sites are designated by dichromic dots. Bisect dichromic dots show sites with well-balanced species proportions, dots with small corner pieces represent sites which are dominated by one species and where the sympatric species is found only in low abundance

DNA extraction, PCR and sequencing

DNA was extracted using either the NucleoSpin® Tissue Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Easton, PA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions or Chelex®-100 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA; Walsh et al. 1991). For DNA extraction using Chelex, tissue was placed in 500 μl of 5% Chelex®-100 in sterile H2O and incubated at 56°C for 4–5 h. After brief vortexing, extracts were incubated at 95°C for 15 min, centrifugated, and then stored at −20°C. Before use, the extracts were centrifugated at 13,000 rpm (10,000g) for 5 min and aliquots (3 μl) of the supernatants were directly used in PCR. PCR amplifications were performed with an amplification profile consisting of a denaturation for 60 s at 94°C, followed by 38 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 50°C and 60 s at 72°C, followed by 5 min at 72°C for final extension. Amplification was carried out using Taq PCR Master Mix Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) in 30 μl reactions containing 3 μl DNA isolate, 3.5 mM MgCl2 and 10 pmol of each primer. For amplification of a 545 bp long fragment of the 16S rDNA gene the following primers were used: 5′-CGCCTGTTTATCAAAAACAT-3′ (16Sar) and 5′-CCGGTCTGAACTCAGATCACGT-3′ (16Sbr; Kessing et al. 1989). The fragment of Cytb gene (450 bp) was amplified using the primers 5′-GG(AT)TA(CT)GT(AT)(CT)T(AT)CC(AT)TG(AG)GG(AT)CA(AG)AT-3′ (CytbF) and 5′-GC(AG)TA(AT)GC(AG)AA(AT)A(AG)(AG)AA(AG)TA(CT)CA(CT)TC(AT)GG-3′ (CytbR; Boore and Brown 2000). The COI gene fragment (709 bp) was amplified using the primers LCOI 1490 (5′-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGT-3′) and HCOI 2198 (5′-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3′) (Folmer et al. 1994). Sometimes HCOI 2198 does not work so we used the newly designed primer HCO709 5′-AAT(AT)AGAAT(AG)TA(GT)ACTTC(AT)GGGTG-3′ instead resulting in a fragment length of 719 bp.

RFLP analysis

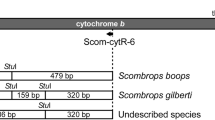

For species identification using restriction fragment polymorphism (RFLP) protocols, the PCR products of 16S and COI were cut using the restriction enzymes ApaI, SspI and AseI (NEB). Within the amplified Cytb gene fragment no species-specific restriction sites were found. The ApaI recognition site (COI) is specific for M. viridis, the SspI recognition site (16S rDNA) is specific for M. neglecta, and the AseI recognition site (16S rDNA) is specific for M. arctia (Tables 2, 3). A 4-μl aliquot of PCR product was directly digested through incubation with 2–3 μl (2 units) of the respective enzyme/NEBuffer mixture at 37°C for 2 h, followed by 30 min at 80°C for inactivation of the restriction enzymes and visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel.

Sequencing

In order to determine restriction sites and to verify the results of the RFLP analysis, PCR products were randomly sequenced. PCR products were purified using the NucleoSpin® Extract Kit (Macherey-Nagel) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and subsequently sequenced directly on the sequencer CEQ 8000 (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) using the CEQ Dye Terminator cycle sequencing quick start kit (Beckman Coulter) and the primers used in initial PCR amplification. The sequences were automatically analysed using the software CEQ2000XL (Beckman Coulter), visually controlled and finally aligned using the Bioedit software (Hall 1999). For species identification and comparison, sequences from M. neglecta from Darss-Zingst Bodden Chain, the Elbe river estuary and the Isle of Rügen (Germany), from M. viridis from the Elbe river estuary (Germany), the Ems estuary (The Netherlands) and the Ringkøbing Fjord (Denmark), and from M. arctia from the Tulom river [Russia; samples provided by A. Sikorski and A. Bick (2004)] were used as species references in the alignments. Bastrop and Blank (2006) showed that each of the three mitochondrial DNA segments allowed an undoubted discrimination of the species.

Starch gel electrophoresis

Starch gel electrophoresis of allozymes was primarily used to detect hybridization between M. neglecta and M. viridis as shown in Blank et al. (2004). In general, the analysis and identification of allozymes using starch gel electrophoresis followed the protocols described in Bastrop et al. (1995) and Röhner et al. (1996a, b). The purpose of this study was to classify the individuals of the populations to either M. viridis or M. neglecta. Therefore, no statistical analyses were done. For >2,000 individuals of each species it was proven that the loci MDH-II* and IDH-II* are to 100% diagnostic between the species M. neglecta and M. viridis (e.g. Röhner et al. 1996a, b). Therefore the populations were screened using these species-specific markers. For discriminating M. arctia from other species, we only used DNA sequencing/RFLP analysis, as there are no allozyme data available, yet.

Results

The analysis of about 950 specimens of more than 30 sampling sites from around the Baltic Sea (Fig. 1, Table 1) using mitochondrial DNA markers and/or starch gel electrophoresis revealed that there are currently three species of the genus Marenzelleria present in the Baltic Sea.

RFLP analysis

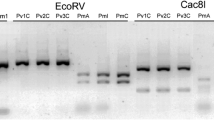

All recognition sites were monomorphic within a given species, thus allowing for an undoubted identification of all three species found in the Baltic Sea (Tables 2, 3). The digestion of 16S rDNA gene fragment using SspI, resulted in M. neglecta in two fragments of ∼227 and 318 bp, while all PCR products from M. viridis and M. arctia remained uncut (Fig. 2). The digestion of 16S rDNA gene fragment using AseI, resulted in M. arctia in two fragments of ∼237 and 308 bp, whereas all PCR products from M. viridis and M. arctia remained uncut (Fig. 2). The enzyme ApaI cuts in the COI gene fragment of M. viridis at the expected site, resulting in two fragments of 309 and 400 bp. No cut was found in M. neglecta and M. arctia (Fig. 2) with this enzyme. To test the reliability of this method we investigated ∼950 specimens of all three species with each restriction enzyme. All specimens of this study as well as all individuals from Bastrop et al. (1998) from European sampling sites and the Atlantic coast of North America were included. In order to develop a fast and cheap method for analysing large sample sizes, we tested our protocol also with DNA isolated by Chelex®-100 (Bio-Rad; Walsh et al. 1991; Bastrop et al. 1998). A single DNA isolation using Chelex®-100 is only one-tenth the prize of an isolation using a commercial isolation kit. Using DNA isolated by Chelex® we obtained the same results as described above and even the subsequent sequencing did not cause any problems. The restriction pattern shown in Fig. 2 did not vary in any of the species that were analysed. The resulting dichotomous molecular identification key is shown in Table 3.

Marenzelleria spp. Digest of PCR products using the restriction enzymes AseI (16S rDNA; a), SspI (16S rDNA; b) and ApaI (COI, c) run on 1.5% agarose gel. Lanes 1, 6 and 11 show undigested PCR products of M. neglecta, M. viridis and M. arctia, respectively. Lanes 2–5, 7–10 and 12–15 show fragment patterns after digest (arrows) for M. neglecta, M. viridis and M. arctia, respectively. Lane M denotes size standard (100 bp ladder) with base pair length indicated on the right side

PCR/sequencing

Sequence data were analysed for a 1,351 bp long dataset combining three mitochondrial DNA sequence segments for a total of 82 specimens. From 16S gene fragment 418 (M. arctia) and 419 (M. neglecta, M. viridis) out of 545 amplified bp, from Cytb 300 out of 450 bp, and from COI fragment 632 out of 709 amplified bp were used in alignment. In addition to the 15 haplotypes published by Bastrop and Blank (2006; Genbank Accession-Nr. DQ309248–DQ309274), 16 new haplotypes were found (Genbank Accession-Nr. EF137718–EF137735; Table A, electronic supplementary material).

For M. neglecta 19 different haplotypes were found at 11 sampling sites (Table 4) with an intraspecific sequence divergence between 0.0 and 1.0%. At Darss-Zingst Bodden Chain (D; Fig. 1), Isle of Rügen (RG), Sandviken (SV) and a bay at the Isle of Askö (BA) only M. neglecta was detected. Near the Isle of Askö (AK), in 30 m depth, one M. neglecta specimen was found sympatric to M. arctia (n = 139). The analysis of specimens of Tvärminne (TV), Pärnu (PÄ), Riga (RI) and Klaipeda (KL) showed only M. neglecta as well. The sampling site in the Gulf of Riga (GR) exhibited a sympatric occurrence of M. neglecta (16 individuals) with M. viridis (five individuals). In the Elbe river estuary (E) M. neglecta occurs partially sympatric to M. viridis.

Seven different haplotypes of M. viridis could be found in nine sampling sites (Table 4). The sequence divergence ranged from 0.0 to 0.3%. Only M. viridis was found at Ringkøbing Fjord (RK; Fig. 1), Ems estuary (EM), Barsebäck (BB), Langenwerder (LW), Warnemünde (W) and Warnow-Breitling (B). The hybrid found at Langenwerder showed the most common M. viridis-specific haplotype Mv1. At Söderhamn (SÖ) one specimen out of five investigated belonged also to this species. The other specimens belonged to M. arctia.

Five specific haplotypes for M. arctia were found at five sampling sites (Table 4). The haplotypes differed by 0.0–0.1% from each other. At three sites [Bothnian Sea (BS), the Åland Sea (AS) and Gulf of Finland (GF)] only M. arctia was found. Sympatric occurrences were found for the other two sampling sites at Söderhamn (SÖ) and Isle of Askö (AK) with M. viridis (single specimen) and M. neglecta (single specimen), respectively. At arctic Tulom River only M. arctia is found. The most common M. arctia haplotype Ma1 (n = 22) is shared by specimens from Tulom River and Baltic Sea sampling sites (AK, SÖ, GF, AS; Table 4).

An inferred phylogeny (Fig. 3) reconstructed from the 31 haplotypes shows the relationships within and between the three Marenzelleria species. No phylogeographic substructure could be identified within species.

Marenzelleria spp. 50%-Majority rule consensus tree (midpoint rooting) from 1,463 MP trees (tree length = 324) reconstructed from composite haplotypes (1,351 bp) of PCR/sequencing data (Table 4; Table A, electronic supplementary material) using PAUP* Version 4.0 b10. Numbers above branches denote bootstrap values above 50%. Abbreviations of sampling sites follow nomenclature in Table 1

Starch gel electrophoresis

Additionally to analyses by PCR-based methods five populations were screened using allozyme electrophoresis (Table 1). Table 5 shows the genotype frequencies at two diagnostic loci for four of these. The population Warnow-Breitling was not included because of the small sample size (five individuals), but all individuals showed alleles specific for M. viridis. In the populations of Ringkøbing Fjord (RK), Warnemünde (W) and the Isle of Langenwerder (LW) only M. viridis specific alleles were found. At the Isle of Langenwerder one individual showed to be a hybrid between M. neglecta and M. viridis at both diagnostic loci studied (MDH-II*: 2–5; IDH-II*: 2–4). Within the population at Rügen (RG) only M. neglecta-specific alleles were detected (Table 5). At the non-diagnostic locus MDH-I*, all individuals showed the genotype 1–1.

Discussion

In a preliminary analysis we showed that with M. arctia and M. viridis two new species of the genus Marenzelleria have invaded the Baltic Sea (Bastrop and Blank 2006). Here, we describe a fast and cheap PCR/RFLP protocol and present a dichotomous molecular identification key for the three Marenzelleria species inhabiting the Baltic Sea (Table 3).

Since 1985, the non-indigenous species M. neglecta has been found in the Baltic Sea (Bick and Burckhardt 1989). By 2001, it seemed that M. neglecta specimens were found even in the northernmost parts of the Gulf of Bothnia (Karlsson and Leonardsson 2003) and the eastern Gulf of Finland (Maximov and Panov 2002). The determination of these specimens was based on morphological identification. Population genetic analyses using allozyme electrophoresis assured the exclusive presence of M. neglecta for seven populations in the Baltic Sea in the middle of the 1990s (Bastrop et al. 1995; Röhner et al. 1996a, b). The occurrence of this species in the upper parts of the Elbe River estuary (North Sea) is the only record from outside the Baltic Sea in European waters, yet (Blank et al. 2004). As Röhner et al. (1996b) we proved M. neglecta at Darss-Zingst Bodden chain in the present study. At more westerly sampling sites only the sibling species M. viridis was detected. At the Isle of Langenwerder a single hybrid was found which may indicate an undetected sympatric occurrence of M. neglecta and M. viridis in the western Baltic Sea. Sequencing of three mitochondrial DNA segments (16S, COI, Cytb) revealed a M. viridis-specific haplotype for this hybrid. The transition area between the North Sea and the Baltic Sea has not yet been investigated as to the current occurrence and distribution of the two species. From the Baltic coastline of Sweden Marenzelleria has been reported since 1990 (Persson 1990); however, the first record from the Swedish west coast dates from 2002 (Göransson et al. 2004; ICES 2005). Species determination again was done by morphological characters, so it is not known which species were involved. Nearby, at Barsebäck, Hittarp, Domsten, Sandön, and Skälderviken (Öresund), we could only detect M. viridis (Fig. 1; sampling sites BB and ÖS). Additionally, a single specimen of M. viridis could be found in 2003 near Fiskebäckskil, Skagerrak area (A. Bick, personal communication). Therefore, we state that in the Skagerrak, Kattegat and in the Öresund M. viridis is the predominant species.

Until 2004, M. viridis was found only in North Sea estuaries and therefore was suggested to be restricted to higher salinities. The surface salinity in the Baltic Sea decreases from the western to the northeastern parts from 24 to 2 ppt. Therefore, the emergence of M. viridis in the western parts of the Baltic Sea was anticipated (Bastrop et al. 1997). For M. viridis, which it is known to have pelagic larvae, there are two potential ways of introduction into the Baltic Sea: by ship ballast water and/or by range expansion from the North Sea through the Kiel Channel or around the Danish peninsula and through the Kattegat and the Danish Straits. The southern coast of the Baltic Sea (Isle of Langenwerder; Warnemünde; Breitling-Warnow estuary, Pomeranian Bight, Puck Bay) was most likely colonized by range expansion. This may have been facilitated by influx of saline waters from the adjacent North Sea. Especially the irregularly occurring major inflows, as observed for example in the year 2003, transport high volumes of water to the southern and central Baltic and their effects on species distribution are clearly discernible even in the Eastern Gotland basin (Segerstråle 1965; Leppäkoski 1971). The genotype frequencies of the diagnostic loci studied (IDH-II* and MDH-II*) are comparable to those found in North Sea populations by Röhner et al. (1996b). The frequencies of the genotypes 2–3 and 3–3 at locus IDH-II* are much higher in all North Sea populations than in populations from North America (Table 5), indicating that range expansion is more likely than a new transatlantic invasion event.

The origin of the single specimen of M. viridis in the Gulf of Bothnia (Söderhamn) was more speculative (Bastrop and Blank 2006). During our present investigations we could find M. viridis at the Gulf of Riga in low abundances (five specimens). Thus, the biannual appearance of pelagic larvae in the northeastern Gulf of Riga (Simm et al. 2003; Kotta et al. 2006) might be explained by the presence of two species. Furthermore, Kotta et al. (2006) documented an increase in the mean annual densities of adult Marenzelleria specimens in Pärnu Bay (Gulf of Riga) in 1997 and another one in 2004. The first one might have been caused by M. neglecta and the second one by M. viridis. Discrepancies in morphological parameters between Marenzelleria specimens from the Gulf of Riga and other Baltic Sea populations (Jermakovs and Cederwall 2003) support the assumption that there are two species involved.

Several authors reported a recent increase in the abundance of Marenzelleria in northern regions and in deeper parts of the eastern Baltic Sea (e.g. Karlsson and Leonardsson 2003). Since 1995, Marenzelleria has been found in small abundances in the coastal waters at Norrbyn (Sweden) in the Bothnian Bay. A steady increase in abundance in the Gulf of Bothnia with highest abundances in Holmöarna (1,778 individuals per m2) was documented by Karlsson and Leonardsson (2003). From 1995 to 2003, abundances increased in coastal waters (Karlsson and Leonardsson 2003). Marenzelleria has been extending its distribution in the open sea also and since 2004 increasing densities up to 4,000 individuals per m2 have been found in the Bothnian and Åland Seas (unpublished data of the Finnish Institute of Marine Research). The results of the present study indicate that this increase in the open sea is obviously caused by the invasion of M. arctia. M. arctia was recorded at five sites in the eastern and northern Baltic Sea (Fig. 1) and therefore for the first time outside the Arctic (Bastrop and Blank 2006). The sympatric occurrence of the species with M. neglecta at the Isle of Askö and with M. viridis at Söderhamn was detected by PCR/sequencing.

Marenzelleria has been reported from the northern Baltic proper (Stockholm and Askö-Landsort area) in low abundances since 1999. In the inner parts of the Stockholm archipelago it occurs in 5–20 m and in the outer area down to 50 m depth (ICES 2001). Slightly increasing abundances were recorded in the last 4 years, but again the species responsible for the increase is unknown. Besides the newly introduced species M. arctia, we also detected M. neglecta in the same area at two sampling sites. At Tvärminne (Gulf of Finland) we found a shift in species occurrence. In samples from 1995 only M. neglecta was proven at this site (Röhner et al. 1996a, b), in 2005, however, M. arctia was found exclusively. It can be anticipated that currently both species are present in this area.

The introduction mechanism of M. arctia into the Baltic Sea is speculative. Baltic M. arctia shared haplotypes with specimens from the Tulom river (Kola Bay, Russia) indicating an origin in the European Arctic (Bastrop and Blank 2006). The most probable way of introduction is by ship ballast water to harbours in the central or northern parts of the Baltic Sea. Nothing is known about the mode of reproduction in M. arctia so far. Transportation by ship ballast water presupposes a pelagic larval phase as in M. viridis and M. neglecta. On condition that pelagic larvae and/or juveniles occur in M. arctia, too, the species might have been introduced by ship and might be responsible for the increasing abundances of Marenzelleria in the Bothnian Sea (Karlsson and Leonardsson 2003; ICES 2005). If M. arctia, like M. neglecta and M. viridis, is not able to reproduce under 5 ppt salinity, but would be able to survive in lower salinities (Bochert et al. 1996), reproducing populations may only be assumed for the southern part of the Bothnian Bay, while the northernmost populations must be recruited each year again from the southern populations of the Swedish or Finnish coast.

The currently known distributions of the species in the Baltic Sea, especially for M. viridis in the southern Bothnian Bay at 4–5 ppt, seem to contradict a solely salinity-dependent distribution. Like the other two species, M. arctia inhabits brackish waters and tolerates salinities from 0 to 32 ppt (Jørgensen et al. 1999). It can be anticipated that M. arctia will spread into further habitats. Due to its arctic origin, however, a restriction to deeper, cooler waters can be assumed. Differences in temperature preferences may results in a vertical segregation: M. arctia colonizes the deeper, cooler habitats (Isle of Askö, 30 m; Himmerfjärden, 20–49 m) whereas M. neglecta is found in shallower waters nearby (Isle of Askö Bay; Sandviken). If this assumption was correct, the Arctic species probably would remain restricted mostly to depths below the summer thermocline in the northern and eastern Baltic Sea. The recent findings show that M. arctia may colonize even the deepest open sea areas in the Baltic Sea, except the central and southern basins, which suffer from semipermanent oxygen depletion (e.g. Laine 2003).

The uncovering of the complex introduction and distribution patterns observed in the Baltic Sea is made difficult by false species determinations and the incorrect use of species names. The genus Marenzelleria consists of five species, which are very difficult to discriminate by morphological characters alone. Discrimination is even impossible in the cases of larvae, juveniles and fragmented specimens. Taxonomic species identification is only possible using a combination of characters or by the inclusion of arithmetical differences between morphological characters (Sikorski and Bick 2004; Bick 2005). However, only molecular markers are able to discriminate the species of the genus Marenzelleria beyond doubt (Bastrop and Blank 2006). Several authors dealing with M. viridis in the Baltic Sea ignored the results of the genetic and taxonomic analyses that clearly showed that the species present in the Baltic Sea is not identical with the one in the North Sea (Bastrop et al. 1995, 1997; Bick and Zettler 1997). A correct species identification and denomination is essential also for interpreting results of ecological and physiological studies. For example, it is likely that M. arctia instead of M. neglecta is responsible for the suggested negative impact on the native amphipod Monoporeia affinis (Neideman et al. 2003). As shown above, the dominant species, which occurs sympatric to M. affinis at 30 m depth near the Isle of Askö is M. arctia. It is also obvious that the reported increase in Marenzelleria abundance and the consequent changes in macrobenthic community structure (e.g. Zettler 1996; Cederwall et al. 1999; Perus and Bonsdorff 2004) are caused by different species in different parts of the Baltic Sea.

The use of molecular techniques in the discrimination of closely related taxa (e.g. sibling species) is well documented (Knowlton 1993) and can facilitate many marine ecological investigations (Burton 1996). With the PCR/RFLP protocol described here, the discrimination of Marenzelleria species is often much easier and more accurate than identification by morphological criteria. Due to the invasion of two other species of the genus into the Baltic Sea, investigations on Marenzelleria require a thorough species determination. The spreading of the three Baltic Marenzelleria species is probably not finished, although the future development and distribution of Marenzelleria spp. in the Baltic Sea is hardly to predict. Whereas M. neglecta is present in most areas of the Baltic Sea, the expansion of M. arctia as well as M. viridis into further areas is a still ongoing process. We anticipate that the distribution of M. arctia may remain restricted to the eastern and northern Baltic Sea, limited by species’ temperature requirements. From the detection of M. viridis in the Bothnian Sea and in the Gulf of Riga we conclude that a further spreading of this species will not be restricted to habitats with higher salinities. Depending on species-specific habitat requirements we expect areas inhabited by only one, by two or even by all three species. Furthermore, we anticipate interspecific competition between Marenzelleria sibling species or between Marenzelleria spp. and other benthic species.

The process of the recent colonization of the Baltic Sea by three species of the genus Marenzelleria is a natural experiment, which allows the investigation of evolutionary and ecological aspects of invasion biology (Segerstråle 1971). Successful colonization mainly depends on the genotype of the immigrant as well as on specific characteristics of the new habitat (abiotic and biotic factors). In this context, future studies on the “niche evolution” of the species were required. Besides, the possible establishment of hybrid zones should be considered. Additionally, investigations at different molecular levels, e.g. nucleic acids and proteins, might offer interesting insights into the speciation process of marine invertebrates.

The results presented here indicate the urgent need for a comprehensive analysis of Marenzelleria populations of the Baltic Sea, the North Sea as well as their transition area to unravel the current distribution of the species and to solve the existing confusion in species denomination.

References

Baltic Sea Alien Species Database (2001) Alien species directory. Olenin S, Leppäkoski E (eds) Coastal Research and Planning Institute, Klaipeda University, Lithuania (http://www.ku.lt/nemo/mainnemo.html)

Bastrop R, Blank M (2006) Multiple invasions—a polychaete genus enters the Baltic Sea. Biol Inv 8:1195–1200

Bastrop R, Jürss K, Sturmbauer C (1998) Cryptic species in a marine polychaete and their independent introduction from North America to Europe. Mol Biol Evol 15:97–103

Bastrop R, Röhner M, Jürss K (1995) Are there two species of the polychaete genus Marenzelleria in Europe? Mar Biol 121:509–516

Bastrop R, Röhner M, Sturmbauer C, Jürss K (1997) Where did Marenzelleria spp. (Polychaeta: Spionidae) in Europe come from? Aquat Ecol 31:119–136

Bick A (2005) A new Spionidae (Polychaeta) from North Carolina, and a redescription of Marenzelleria wireni Augener, 1913, from Spitsbergen, with a key for all species of Marenzelleria. Helgol Mar Res 59:265–272

Bick A, Burckhardt R (1989) First record of Marenzelleria viridis (Polychaeta, Spionidae) in the Baltic Sea, with a key to the Spionidae of the Baltic Sea. Mitt Zool Mus Berlin 65:237–247

Bick A, Zettler ML (1997) On the identity and distribution of two species of Marenzelleria in Europe and North America. Aquat Ecol 31:137–148

Blank M, Bastrop R, Röhner M, Jürss K (2004) Effect of salinity on spatial distribution and cell volume regulation in two sibling species of Marenzelleria (Polychaeta: Spionidae). Mar Ecol Prog Ser 271:193–205

Bochert R, Fritzsche D, Burckhardt R (1996) Influence of salinity and temperature on growth and survival of the planktonic larvae of Marenzelleria viridis (Polychaeta, Spionidae). J Plankton Res 18:1239–1251

Boore J, Brown WM (2000) Mitochondrial genomes of Galathealinum, Helobdella, and Platynereis: sequence and gene arrangement comparisons indicate that Pogonophora is not a phylum and Annelida and Arthropoda are not sister taxa. Mol Biol Evol 17:87–106

Burton RS (1996) Molecular tools in marine ecology. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 200:85–101

Carlton JT, Geller JB (1993) Ecological roulette: global transport of nonindigenous marine organisms. Science 261:78–82

Cederwall H, Jermakovs V, Lagzdins G (1999) Long-term changes in the soft-bottom macrofauna of the Gulf of Riga. ICES J Mar Sci 56:41–48

Elliott M, Kingston PF (1987) The sublittoral benthic fauna of the estuary and Firth of Forth, Scotland. Proc R Soc Edinburgh 93B:449–465

Essink K, Dekker R (2002) General patterns in invasion ecology tested in the Dutch Wadden Sea: the case of a brackish-marine polychaetous worm. Biol Inv 4:359–368

Essink K, Kleef HL (1993) Distribution and life cycle of the North American spionid Marenzelleria viridis (Verrill, 1873) in the Ems estuary. Neth J Aquat Ecol 27:237–246

Folmer O, Black M, Hoen W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R (1994) DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Biotech 3:294–299

Gollasch S, Dammer M, Lenz J, Andres HG (1998) Non-indigenous organisms introduced via ships traffic into German waters. In: Carlton JT (ed) Ballast water: ecological and fisheries implications. ICES Coop Res Rep 224:50–64

Göransson P, Börjesson L, Karlsson M (2004) Kustkontrollprogram för Helsingborg. Årsrapport 2003

Gruszka P (1991) Marenzelleria viridis (Verrill, 1873) (Polychaeta: Spionidae)—a new component of shallow water benthic community in the southern Baltic. Acta Ichthyol Pisc 21(Suppl):57–65

Hall TA (1999) Bioedit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser 41:95–98

ICES (2001) Report of the working group on introductions and transfers of marine organisms. Barcelona, Spain

ICES (2005) Report of the working group on introductions and transfers of marine organisms. Barcelona, Spain

Jansson K (1994) Alien species in the marine environment. Swedish Environment Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden, Rep. 4357

Jermakovs V, Cederwall H (2003) Distribution and morphological parameters of the polychaete Marenzelleria viridis population in the Gulf of Riga. In: Dahlin H, Dybern B, Petterson S (eds) Proceedings of the Baltic marine science conference, Rønne, Denmark, 22–26 October 1996. ICES Coop Res Rep 257:21–28

Jørgensen LL, Pearson TH, Anisimova NA, Gulliksen B, Dahle S, Denisenko SG, Matishov GG (1999) Environmental influences on benthic fauna associations of the Kara Sea (Arctic Russia). Polar Biol 22:395–416

Karlsson A, Leonardsson K (2003) Mjukbottenfauna. In: Wiklund K (ed) Bottniska viken. Umeå marina forskningcentrum, Umeå University, Sweden, pp 14–16

Kessing B, Croom H, Martin A, McIntosh C, Owen McMillan W, Palumbi S (1989) The simple fool’s guide to PCR. University of Hawaii, Honolulu

Knowlton N (1993) Sibling species in the sea. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 24:189–216

Kotta J, Kotta I (1998) Distribution and invasion ecology of Marenzelleria viridis in the Estonian coastal waters. Proc Estonian Acad Sci Biol Ecol 47:212–220

Kotta J, Kotta I, Simm M, Lankov A, Lauringson V, Põllumäe A, Ojaveer H (2006) Ecological consequences of biological invasions: three invertebrate case studies in the north-eastern Baltic Sea. Helgol Mar Res 60:106–112

Kube J, Zettler ML, Gosselck F, Ossig S, Powilleit M (1996) Distribution of Marenzelleria viridis (Polychaeta: Spionidae) in the southwestern Baltic Sea in 1993/94—ten years after introduction. Sarsia 81:131–142

Kullenberg G, Jacobsen TS (1981) The Baltic Sea: an outline of its physical oceanography. Mar Poll Bull 12:183–186

Laine AO (2003) Distribution of soft-bottom macrofauna in the deep open Baltic Sea in relation to environmental variability. Est Coast Shelf Sci 57:87–97

Lagzdins G, Pallo P (1994) Marenzelleria viridis (Verrill) (Polychaeta, Spionidae)—a new species for the Gulf of Riga. Proc Estonian Acad Sci Biol Ecol 43:184–188

Leonardsson, K (2001) Mjukbottenfauna. In: Wiklund K (ed) Bottniska viken 2000. Årsrapport från den marina miljöövervakningen. Umeå Marina Forskningscentrum

Leppäkoski E (1971) Benthic recolonization of the Bornholm Basin (Southern Baltic) in 1969–71. Thalassia Jugosl 7:171–179

Leppäkoski E (1984) Introduced species in the Baltic Sea and its coastal ecosystems. Ophelia Suppl 3:123–135

Leppäkoski E, Gollasch S, Gruszka P, Ojaveer H, Olenin S, Panov V (2002) The Baltic—a sea of invaders. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 59:1175–1188

Matthäus W, Nausch G (2003) Hydrographic-hydrochemical variability in the Baltic Sea during the 1990s in relation to changes during the 20th century. ICES Mar Sci Symp 219:132–143

Maximov AA, Panov VE (2002) Expansion of Marenzelleria viridis (Polychaeta: Spionidae) in the eastern Gulf of Finland. Symposium—the changing state of the Gulf of Finland ecosystem, Tallinn

Neideman R, Wenngren J, Ólafsson E (2003) Competition between the introduced polychaete Marenzelleria sp. and the native amphipod Monoporeia sp. in Baltic soft bottoms. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 264:49–55

Ojaveer H, Leppäkoski E, Olenin S, Ricciardi A (2002) Ecological impact of Ponto-Caspian invaders in the Baltic Sea, European inland waters and the Great Lakes: an inter-ecosystem comparison. In: Leppäkoski E, Gollasch S, Olenin S (eds) Invasive aquatic species of Europe. Kluwer, Dordrecht, pp 412–425

Olenin S, Chubarova S (1992) Recent introduction of the North American spionid polychaete Marenzelleria viridis (Verrill, 1873) in the coastal areas of the southeastern part of the Baltic area. International symposium—function of coastal ecosystems in various geographical regions, Gdansk University

Persson L-E (1990) The national Swedish environmental monitoring programme (PMK): soft-bottom macrofauna monitoring off the south coast of Sweden—annual report 1990. Naturvårdsverket Rapport 3937:5–12

Perus J, Bonsdorff E (2004) Long-term changes in macrozoobenthos in the Åland archipelago, northern Baltic Sea. J Sea Res 52:45–56

Röhner M, Bastrop R, Jürss K (1996a) Genetic differences between two allopatric populations (or sibling species?) of the polychaete genus Marenzelleria in Europe. Comp Biochem Physiol 114B:185–192

Röhner M, Bastrop R, Jürss K (1996b) Colonization of Europe by two American genetic types or species of the genus Marenzelleria (Polychaeta: Spionidae). An electrophoretic analysis of allozymes. Mar Biol 127:277–287

Segerstråle SG (1965) On the salinity conditions off the south coast of Finland since 1950, with comments on some remarkable hydrographical and biological phenomena in the Baltic area during this period. Comm Biol 28:1–28

Segerstråle SG (1971) Aspects of the biology of the Baltic Sea, with special refernece to the littoral zone. In: Riser NW, Carlson GA (eds) Cold water inshore marine biology. Some regional aspects. Northeastern University Science Institute, Boston, pp 7–13

Sikorski AV, Bick A (2004) Revision of Marenzelleria Mesnil, 1896 (Spionidae, Polychaeta). Sarsia 89:253–275

Simm M, Kukk H, Viitasalo M (2003) Dynamics of Marenzelleria viridis (Polychaeta: Spionidae) pelagic larvae in Pärnu Bay, NE Gulf of Riga, in 1991–99. Proc Estonian Acad Sci Biol Ecol 52:394–406

Stigzelius J, Laine A, Rissanen J, Andersin A-B, Ilus E (1997) The introduction of Marenzelleria viridis (Polychaeta, Spionidae) into the Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Bothnia (northern Baltic Sea). Ann Zool Fennici 34:205–212

Walsh PS, Metzger DA, Higuchi R (1991) Chelex 100 as a medium for simple extraction of DNA for PCR-based typing from forensic material. Biotechniques 10:506–513

Zettler ML (1996) Successful establishment of the spionid polychaete Marenzelleria viridis (Verrill, 1873), in the Darss-Zingst estuary (southern Baltic) and its influence on the indigenous macrozoobenthos. Arch Fish Mar Res 43:273–284

Zmudzinski L, Chubarova-Solovjeva S, Dobrowolski Z, Gruszka P, Fall I, Olenin S, Wolnomiejski N (1997) Expansion of the spionid polychaete Marenzelleria viridis in the southern part of the Baltic Sea. In: Andrushaitis A (ed) Proceedings of the 13th symposium Baltic marine biologists, Riga, Institute of Aquatic Ecology, University of Latvia, pp 127–130

Acknowledgments

The authors thank (in alphabetical order) A. Bick, H. Brocke, S. Ericsson, J. Frankowski, I. Glockzin, P. Göransson, J. Große, K. Meissner, M. Powilleit, M. Röhner, S. Schläger, D. Schulz-Bull, K. Schwandt, A. Sikorski and M.L. Zettler for their kind help.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by H.-D. Franke.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blank, M., Laine, A.O., Jürss, K. et al. Molecular identification key based on PCR/RFLP for three polychaete sibling species of the genus Marenzelleria, and the species’ current distribution in the Baltic Sea. Helgol Mar Res 62, 129–141 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-007-0081-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-007-0081-8