Abstract

Animal remains are well preserved in archaeological sites, especially the terp sites, of the Wadden Sea area of Denmark, Germany and The Netherlands. Here, we provide an overview on the wild mammals, birds, fishes, amphibians and molluscs found in coastal sites dating from 2700 to 2600 B.C. and 700 B.C. to A.D. 1600. Coastal people used a variety of animal species for food and other purposes. Hunting, fowling, fishing and agriculture did not have much influence on wild stocks in the period from the late Bronze Age/early Iron Age until the late Middle Ages. However, large changes to the landscape were made in the late Middle Ages by diking and damming. As a result, some species such as the northern vole (Microtus oeconomus) and the natterjack toad (Bufo calamita) disappeared from the area except for some dune districts on the islands, and others became rare, such as the grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) and the lagoon cockle (Cerastoderma lamarcki). New habitats arose for birds of dry meadows and fields, like lapwing (Vanellus vanellus) and black-tailed godwit (Limosa limosa). Sturgeon (Acipenser sturio) disappeared from the Wadden Sea within a few decades since A.D. 1890 due to the destruction of spawning grounds by damming and high exploitation pressure. Our findings are important for the ecological history of the region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Archaeozoological evidence contributes to the ecological history of the Dutch, German and Danish Wadden Sea area. This evidence is obtained from the hard remains of animals that lived on sites used by man or had been brought to them by man. Animal remains, mainly bones, antlers, teeth and mollusc shells, are well preserved in archaeological sites in the Wadden Sea area due to the excellent preservation conditions.

If we use archaeozoological evidence to reconstruct past environments and faunas, we should be aware of the bias that this type of evidence is liable to. There are three sources of bias. The first is the selectivity of the inhabitants of the sites. Cultural customs, preferences, taboos, skills, trade and the way garbage was deposited determine whether the remains of species may be found in a site or not. Animal remains from archaeological sites are of cultural interest in the first place, and of ecological interest only in the second place.

The second source of bias is the diagenesis in the soil, which may have favoured the preservation of some remains and caused the destruction of others. The third is the choices made by the excavator and the archaeozoologist: which part was excavated, was sieving of soil samples practiced to recover bird and fish remains, which groups were identified. Only the third factor may be influenced by archaeologists and archaeozoologists (Reitz and Wing 1999).

The Wadden sea area is an always-changing landscape. The changes are twofold: natural ones and anthropogenic ones. The Holocene sea-level rise resulted in the formation of salt marshes, intertidal flats and gullies along the coast of the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark. The salt marshes varied from rather high, sandy ones to low, clayey ones. Salt marshes bordering a then existing lagoon in the north of the Dutch province Noord-Holland were inhabited during the Neolithic (Theunissen 2001; Zeiler 1997).

Floods around 1250 B.C. made habitation of the Wadden Sea area impossible. New salt marshes developed after about 1000 B.C. The salt marsh was high enough to be occupied by about 700 B.C. The Wadden Sea landscape was attractive for dwelling, pasturing livestock, arable farming, fishing, fowling and gathering. People raised artificial dwelling mounds in the salt marsh, the terp sites (terpen, wierden or Wurten). Peat digging in the hinterland started in the ninth and tenth centuries A.D. in the Netherlands as well as in parts of the German coastal area, e.g. Nordfriesland. This contributed to the birth of large floods, which resulted in the building of dikes from the twelfth century A.D. onwards. Over time, a complete landscape of salt marshes transected by gullies and a gradual fresh-saline transition disappeared (Zagwijn 1986; Prummel 1999).

The archaeozoological evidence presented in this paper shows that the natural conditions of the Wadden Sea area offered the people good living conditions. The anthropogenic influence on the environment was restricted (or immeasurable by archaeozoologists) before the building of dikes and the damming of gullies. These habitat-transforming activities, however, and the increase in human population and exploitation pressure during the late Middle Ages had a strong influence on the fauna, as is shown by the examples of sturgeon, natterjack toad, moor frog (Rana arvalis), white-tailed eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla), lapwing, black-tailed godwit, northern vole, aurochs (Bos primigenius), grey seal and lagoon cockle.

Methods

The archaeozoological remains of a large number of sites were identified by various authors (Table 1) with the aid of the reference collections of modern skeletons at the University of Kiel/Archäologisches Landesmuseum Schleswig, the University of Groningen and the Zoological Museum of Copenhagen. Identification was based on morphological differences between the skeletons of various species. The remains of closely related species, i.e. within a genus, may be impossible to separate, especially when the remains are heavily fragmented. This is mostly the case with archaeozoological material from settlements, which is mainly kitchen refuse.

The sites used for this paper date to the period 2700–2600 B.C. (late Neolithic) and 700 B.C.–A.D. 1600 (Iron Age to late Middle Ages) (Table 1). The modern ecological requirements of the various species are considered in the interpretation of the data (the actualistic principle). The presence and the relative abundance of a species in a specific site or phase are considered to some extent as indications of the presence and the abundance of the species in the area. However, the human selectivity has always to be considered in drawing conclusions on the absence of a species in archaeozoological materials and on changes in its abundance.

Written sources and pictures of animals were considered as well. However, they are only available for the historical periods, and are rather poor. Identification of the depicted animals proved to be problematic (Prummel 2001).

Results and discussion

Fishes

Pleuronectids and gadids were most abundant in most of the sites (Table 2). This was expected because the pleuronectids live in the Wadden Sea and, furthermore, gadids and pleuronectids could be derived from merchandise. Freshwater fishes were unimportant in the terp sites at all times. The exception is the material from Zweins. However, this deposit is from a late medieval moat, and most fish remains are derived from one individual of roach (Rutilus rutilus). Pike (Esox lucius), perch (Perca fluviatilis) and carp (Cyprinidae) are represented in several of the other materials (Table 2).

Sturgeon is only frequent in settlements near the mouth of rivers, which this species used on migrations for spawning. Examples are Elisenhof on the river Eider and Feddersen Wierde at the river Weser. Remains of sturgeon are also known from settlements on the lower Ems, namely Boomborg-Hatzum, Bentumersiel and Jemgumkloster (Table 2). Particularly the rivers Eider and Weser, but surely also others, like the Elbe, as is known from historical records, and Ems, offered spawning grounds for the sturgeon. Lots of remains of sturgeon, especially the scutes and subopercularia, were found at Elisenhof and Feddersen Wierde, and most of them point to very large specimens (Fig. 1).

Sturgeon, Acipenser sturio. 1 Cleithrum, 2 Suboperculare; a bones of a recent individual of 110 cm total length, b,c finds from Elisenhof; after Heinrich (1994)

Of course, the frequencies of remains of this large species with large bones are biased in hand-collected material. Nevertheless, the absolute numbers give an idea of its importance. Nearly 3/4 of the fish remains from Roman times in the village of Feddersen Wierde near the mouth of the Weser, and 1/4 of the fish remains in the medieval village of Elisenhof, situated at the Eider estuary, are derived from sturgeon.

The human influence on the sturgeon was manifold. Deepening and straightening and especially damming up of tributaries, which blocked the movements of migratory fish, had already started in the Eider in the sixteenth century. Most disastrous was its damming up near Nordfeld in 1936. From this date onward it was impossible for sturgeon to reach any spawning ground. The most recently built dam near the mouth of the river was the final point in this development. Other factors were inconsiderate fishery in the rivers and the Wadden Sea, and water pollution. The decline of the species is shown by the decline of the fishery from the last decade of the nineteenth century onwards. The fishery totally collapsed around 20 years later (Spratte 2001; Lotze 2005).

Other migratory species found in sites in the Wadden Sea area are the euryoecious (adaptable) eel (Anguilla anguilla), which was found at several sites, and the salmon-trout group, which is very frequent at Ribe (Table 2).

Of special interest are species that mainly have a southern distribution, like thornback ray (Raja clavata), European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax), Atlantic horse mackerel (Trachurus trachurus), meagre (Argyrosomus regius) and the grey mullets (Mugilidae). The remains of these species are rare at most sites. Exceptions are Ribe with 144 remains of the thin-lipped grey mullet (Liza ramada), and Lembecksburg with 26 remains of the thick-lipped grey mullet (Chelon labrosus). These species may point to relatively shallow and warm waters and may have been more or less rare summer visitors. Today they are known in the Wadden Sea only in summer, if at all. Only the thornback ray is a regular summer visitor. Shallow and warm waters attractive for these fish species perhaps became rarer after the closing of gullies.

Amphibians

Amphibian remains most probably refer to the natural fauna, which means that man did not influence the presence of remains of this group in archaeological sites. What is important is that they are ecologically sensitive and can be used to identify the availability of former habitats. However, their remains are rare in archaeological contexts, especially if no sieving was employed.

Only four species have been identified. One bone points to the common frog (Rana temporaria), a ubiquitous species without special ecological demands. Most of the remains are derived from the natterjack toad. The moor frog is also of importance, and we will mention the green toad (Bufo viridis) (Table 3).

B. calamita was found on two islands: Föhr (Dunsum site), a partly morainic island, and Texel (Oudeschild site), a barrier island with a morainic part (De Hoge Berg) near Oudeschild. It is also known from the terp sites Feddersen Wierde, Wijnaldum and Oosterbeintum. The last site yielded nearly 1,600 finds. B. calamita prefers sandy areas with little vegetation, like dunes. Its demands on waters for spawning are low and since it contents itself even with ephemeral and slightly brackish pools, it is to be expected on the islands.

Today, the species lives in Schleswig-Holstein in dune areas and in other more or less sandy parts, like the “Geest”. In the north of the Netherlands it occupies the barrier islands and the peat area (Bergmans and Zuiderwijk 1986). The species does not live in the diked coastal clay areas of Germany and the Netherlands now, but was found in earlier times in Feddersen Wierde, Wijnaldum and Oosterbeintum. As these were terp sites in the undiked salt marsh, it is to be concluded that sandy parts must have existed in the vicinity.

R. arvalis can spawn in temporary pools. However, it likes them to have dense vegetation. It prefers habitats with a high watertable. It obviously found such conditions in the undiked salt marsh. It is uncertain whether the four anuran bones from Feddersen Wierde determined as remains of B. viridis really belong to this species. B. viridis is a southeastern steppe species. Its present distribution does not reach to the coastal area of the North Sea. The conclusion on the amphibian remains is that B. calamita and R. arvalis lost suitable habitats in the former salt marsh after the building of dikes.

Birds

Birds found in the late Neolithic site of Kolhorn on the west coast of the Netherlands (2700–2600 B.C.) represent species from a variety of habitats such as the seashore, tidal flats, salt marshes, marshes, swamps, meadows and arable fields (Zeiler 1997) (Table 4). Ducks of the genera Anas and Mareca are very well represented (more than 50% of all finds), as well as waders and the white-tailed eagle. The great crested grebe (Podiceps cristatus) and the red-crested pochard (Netta rufina) suggest lakes or ponds were present near the site (Table 4).

The bird remains found in terp sites from the period 700 B.C. until the twelfthth century A.D., i.e. before the period of dike building, also represent various environments. People used a great variety of bird species. Most numerous are the remains of species from tidal flats, salt marshes, swamps, meadows and arable fields such as ducks, mainly of the genera Anas and Mareca, geese and waders, especially of the genera Calidris, Philomachus, Tringa and Pluvialis (Table 4).

Ducks continued to be the most common wild bird species in archaeozoological materials after the building of dikes. The stress is now even more on the genera Anas and Mareca, which will be ducks captured in duck decoys. In contrast, waders became rarer in the bone materials, presumably because they were hunted less. An exception is the golden plover (Pluvialis apricaria), which was still regularly captured, presumably with a special fowling method, the wilstervangst (Jukema et al. 2001), on the former salt marshes. The finds of sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus) and kestrel (Falco tinnunculus) in the town of Leeuwarden are perhaps associated with hawking (Prummel 1997). The white-tailed eagle is represented in layers as late as the tenth and eleventh centuries A.D., but disappeared from the Wadden Sea area thereafter, probably because of hunting pressure and habitat loss.

Some species are strikingly lacking or rare in the bone materials from the pre- and the post-dike-building periods: for example, lapwing and black-tailed godwit. Today they are common breeding birds on the former salt marshes in the Netherlands (Schekkerman 2002; Wymenga 2002). These species presumably became more numerous after dry meadows and arable fields arose on the former salt marshes after the building of dikes.

Mammals

Most sites show no wild mammal remains at all, or only in small numbers. Hunting of wild mammals was of some importance in the late Neolithic site of Kolhorn and of almost no importance in the terp sites, perhaps because of the rarity of game in the salt marsh (Tables 5, 6). Aurochs, red deer (Cervus elaphus), elk (Alces alces), the northern vole and the marine mammals are worthy of some comments.

Aurochs remains are found in small numbers in salt marsh sites. The latest evidence is from the Wurt of Elisenhof in Schleswig-Holstein: eighth to thirteenth centuries A.D. (Reichstein 1994). An almost complete skeleton of a male aurochs was found in the Dutch terp site Britsum. It dates from between the end of the third and the beginning of the fifth century A.D. (Clason and van Es 1992, 1993). Aurochs presumably lived in low numbers in the salt marsh.

Most of the red deer and elk finds in the terp sites are antler fragments: mainly tools, like combs and awls, or waste from tool production. These remains will not represent animals that lived on the salt marsh. Red deer and elk antlers were obviously imported as raw materials to the salt marshes in the Roman period and the early Middle Ages.

A habitat change is reflected in the bones of the northern vole in terp sites. The species is represented in four terp sites that date from before the building of dikes (Elisenhof, Feddersen Wierde, Oosterbeintum and Wijnaldum). It apparently lived on the salt marsh, perhaps on more sandy areas (Table 5). It was also found in four Neolithic wetland sites in the northern part of the Dutch province Noord-Holland: Kolhorn (Zeiler 1997; Table 5), Zeewijk, Bouwlust and Keinsmerbrug (Theunissen 2001). The modern Dutch northern vole population is a western relic of the original European population (Ligtvoet 1992; van Apeldoorn 1999). Finds from northern Germany show that the species still occurred there in the first millennium A.D. (Table 5).

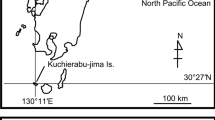

The northern vole lives in reedlands, swamps, moist meadows, extensively used pastures and marshy riverbanks. Today it occupies five isolated wet, low-lying areas in the lower parts of The Netherlands (Fig. 2) (Ligtvoet 1992). The Convention of Bern obliges The Netherlands to take measures to protect it. The northern vole is absent in the former salt marsh area at present. The common vole (Microtus arvalis) is the only vole species there today.

The 1970–1988 distribution of the northern vole (Microtus oeconomus) in The Netherlands (closed circles finds of living or dead animals; open circles pellet finds) (after Ligtvoet 1992, p 277) in comparison with the archaeological finds 1–3. 1 part of Noord-Holland with the sites Kolhorn, Zeewijk, Bouwlust and Keinsmerbrug; 2 Wijnaldum; 3 Oosterbeintum. 4 is the salting Tiendgorzen, that was transformed from arable into marsh in 2001, and was colonised by the northern vole in 2003

The building of the dikes destroyed the northern vole habitats in the salt marshes. The area obviously became too dry for the species and offered insufficient shelter. That the northern vole may occupy suitable new habitat was demonstrated in November 2003, when the species was encountered on the salting of Tiendgorzen (province of Zuid-Holland, The Netherlands) (Fig. 2). This salting had been transformed from arable into marsh in 2001 (Kierkels 2004).

Two species of seal can be expected in the Wadden Sea: the harbour seal (Phoca vitulina), which is common, and the grey seal, of which present colonies are only known in the Wadden Sea on flats off Amrum (Germany) and on flats between Vlieland and Terschelling (Netherlands). Both colonies have developed recently.

Colonies of grey seal obviously existed in the Dutch and the German parts of the Wadden Sea in earlier times. The last is shown by the finds of the Lembecksburg on the island of Föhr (Germany). However, harbour seal colonies probably existed in earlier times as well. This is shown by the many remains of this species found in the Feddersen Wierde from the pre-dike-building period. The sites Elisenhof and Lembecksburg, which belong at least partly to the pre-dike-building epoch, yielded remains of harbour seals as well (Table 6).

The grey seal was relatively frequent until about the tenth century A.D. according to the number of remains (Table 6), whereas the harbour seal presumably became more important in the late Middle Ages and up to now. The decrease of the grey seal is due to higher disturbance by man from the twelfth century onwards, after the dikes had been built (Prummel 1999). The pups, which are born in winter, wear their foetal lanugo-coat, which protects them against cold and wet. However, in this coat they cannot swim because it lets water through. Thus the grey seal needs safe, unflooded places in order to give birth to its young. Such places became rare with the growing human population, but also with the rising tidal amplitude. The sandbanks became flooded to a higher degree than before dike building and the damming up of gullies.

The growing population of the harbour seal, which was rare in other parts of northern Europe such as the Baltic in prehistoric times as well (Clark 1946), has not yet been explained. However, it is to be supposed that this species was not really affected by a rising tidal amplitude connected with flooded sandbanks, as its young are able to swim within some hours after birth (Reijnders 1992).

The common porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) is the most numerous cetacean species in the material. Today it is the most abundant cetacean species in the North Sea and the Baltic. This was obviously also true in earlier times. The bottle-nosed dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) takes second place today and in the past. Some remains of other cetacean species were found as well (Table 6). That is not surprising, for many of them are cosmopolitans, and strandings still occur.

Molluscs

Coastal inhabitants in former times regularly consumed a variety of shellfish such as Cerastoderma edule, Mytilus edulis, Ostrea edulis, Littorina littorea and Buccinum undatum. Smaller tidal flat molluscs represented in some sites are probably accidental finds (Table 7).

Two Cerastoderma species are represented: the common cockle, Cerastoderma edule (Linnaeus, 1758), which lives in marine habitats, and the lagoon cockle, Cerastoderma lamarcki (Reeve, 1844), which lives in estuarine, brackish habitats (Table 7). That two Cerastoderma species have been present in northern and western Europe only became clear in the 1980s (Brock 1991; Poppe and Goto 1993). C. lamarcki was recognized in natural deposits at two sites in the Dutch part of the Wadden Sea area: Hemert-Arum (Late Bronze Age/Iron Age) and Heveskesklooster (presumably fourteenth century). The Heveskesklooster lagoon cockles developed in the outer and inner moats of the medieval monastery there (date ca. A.D. 1300–1610) after a dike break along the river Ems (Prummel and Knol 2005).

Today C. lamarcki is rare in the Dutch and German parts of Wadden Sea. It was recognized alive in a large creek on the island of Schiermonnikoog in 2003 (van Leeuwen 2003). It occurs in ditches, creeks and ponds on the island of Sylt (Reise 2003). In contrast, this species was more common in the past (also Kuijper 2001) for neolithic sites in Noord-Holland). This is shown by the dead valves that are found in the Dutch Wadden Sea (de Boer and de Bruyne 1991). The brackish, estuarine conditions favourable for C. lamarcki became rare after the building of the dikes.

Conclusions

The animal groups discussed here suggest that human activities in the centuries before the late Middle Ages, for instance the erasing of terp sites, arable farming, pasturing, hunting, fishing, and fowling, did not seriously affect the Wadden Sea area and its fauna. The human impact on the wild fauna increased when diking and damming started in about the twelfth century A.D. and the human population and the exploitation of wild animals increased.

We conclude that some species disappeared from the Wadden Sea area or lost large areas of habitat little by little because of hunting, the dense human population, and habitat destruction due to the building of dikes. This holds for aurochs, northern vole, white-tailed eagle, natterjack toad and moor frog. Estuarine, brackish conditions disappeared, resulting in the decline of the lagoon cockle. A new habitat for birds and mammals of dry meadows and arable fields arose, like that for lapwing, black-tailed godwit and the common vole. The sturgeon disappeared within a few decades since A.D. 1890 due to damming and high exploitation pressure. Any changes in the presence of many other species may be invisible for us because of the human selection bias in archaeological sites.

References

Apeldoorn, RC van (1999) Microtus oeconomus (Pallas, 1776). In: Mitchell AJ (ed) The atlas of European mammals. T & AD Poyser, London, pp 244–245

Bergmans W, Zuiderwijk ACM (1986) Atlas van de Nederlandse amfibieën en reptielen en hun bedreiging. Stichting Uitgeverij KNNV, Hoogwoud

Boer TW de, Bruyne RH de (1991) Schelpen van de Friese Waddeneilanden. Fryske Akademy, Ljouwert/Dr. W. Backhuys/U.B.S., Oegstgeest

Brinkhuizen DC (1983) Visresten uit twee middeleeuwse vindplaatsen te Leeuwarden. In: Zeist W van, Neef R, Brinkhuizen DC, Jager S (eds) Planten- Vis- en Vogelresten uit vroeghistorisch Leeuwarden. Commissie Archeologisch Stadskernonderzoek Leeuwarden. Leeuwarden, pp 19–20

Brinkhuizen DC (1988a) Vis en visvangst bij de terpbewoners. In: Bierma M, Clason AT, Kramer E, Langen GJ de (eds) Terpen en wierden in het Fries-Groningse kustgebied. Wolters-Noordhoff/Forsten, Groningen, pp 226–233

Brinkhuizen DC (1988b) Archeo-zoölogisch onderzoek van de beerkuil; de visresten. In: Adolfs F (ed) Kattendiep deurgraven. Historisch-archeologisch onderzoek aan de noordzijde van het Gedempte Kattendiep te Groningen. Stichting Monument en Materiaal, Groningen, pp 167–174

Brock V (1991) An interdisciplinary study of evolution in the cockles, Cardium (Cerastoderma) edule, C. glaucum, and C. lamarcki. Vestjydsk Forlag, Vinderup

Clark JGD (1946) Seal-hunting in the stone age of north-western Europe: a study in economic prehistory. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society for 1946. NS 12, pp 12–48

Clason AT (1962) Beenderen uit nederzettingssporen van rond het begin onzer jaartelling bij Sneek. De Vrije Fries 45:102–112

Clason AT (1988) De grijze zeehond Halichoerus grypus (Fabricius, 1791). In: Bierma M, Clason AT, Kramer E, Langen GJ de (eds) Terpen en wierden in het Fries-Groningse kustgebied. Wolters-Noordhoff/Forsten, Groningen, pp 234–240

Clason AT, van Es L (1992) De oeros-it Bos primigenius-van Britsum (Fr). Paleo-Aktueel 3:81–83

Clason AT, van Es L (1993) De oeros-it Bos primigenius-van Britsum (Fr) gedateerd. Paleo-Aktueel 4:110

Clason AT, Prummel W (1982) Faunaresten uit een vroeg-middeleeuwse nederzetting bij Schagen: Waldervaart. Westerheem 31:69–77

Enghoff I Bødker (2000) Fishing in the southern north Sea region from the 1st to the 16th Century AD: evidence from fish bones. Archaeofauna 9:59–132

Ewersen J (1999) Die Tierreste des mittelalterlichen Fundplatzes Alt-List auf Sylt, Kr. Nordfriesland. Offa 54/55 (1997/98):425–430

Gelder-Ottway SM van (1988) Animal bones from a pre-roman iron age coastal marsh site near Middelstum (province of Groningen, the Netherlands). Palaeohistoria 30:125–144

Giffen AE van (1913) Die Fauna der Wurten. EJ Brill, Leiden

Grimm J (2003) Untersuchungen an Tierknochen aus der jungbronzezeitlichen Flachsiedlung Rodenkirchen-Hahnenknooper Mühle, Ldkr. Wesermarsch, mit einem Exkurs zu den Knochengeräten. Probleme der Küsterforschung im südlichen Nordseegebiet 28:185–234

Halici H (1997) Gebruiksvoorwerpen van been en gewei uit Tjitsma, Wijnaldum. Unpublished master thesis, University of Groningen

Halici H (2002) Faunaresten. In: Koopstra CG (ed) Archeologisch onderzoek op de wierde Baflo, provincie Groningen. ARC-publicatie 47. ARC, Groningen, pp 39–64

Heinrich D (1991) Die Fische, Pisces. In: Reichstein H Die Fauna des Germanischen Dorfes Feddersen Wierde Feddersen Wierde 4. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart, pp 293–301

Heinrich D (1994) Die Fischreste aus der frühgeschichtlichen Wurt Elisenhof. Studien zur Küstenarchäologie Schleswig-Holsteins Seria A. Elisenhof 6. Peter Lang, Frankfurt/Main, Berlin, Bern, New York, Paris, Wien, pp 215–249

Hopman M (1993) Een kijk op het Karolingische dierenrijk; Faunaresten van de terpen Tzummarum en Wijnaldum (Fr). Unpublished master thesis, University of Groningen

Jukema J, Piersma T, Hulscher JB, Bunskoeke EJ, Koolhaas A, Veenstra A (2001) Goudplevieren en wilsterflappers, eeuwenoude fascinatie voor trekvogels. Fryske Akademy, Ljouwert/KNNV Uitgeverij, Utrecht

Kierkels, T (2004) Nieuwe plek voor kieskeurige muis. Natuurbehoud 35:12–13

Knol E (1986) Farming on the banks of the river Aa. The faunal remains and bone objects of Paddepoel 200 B.C.–250 A.D. Palaeohistoria 25(1983):145–182

Knol E, Prummel W, Uytterschaut HT, Hoogland MLP, Casparie WA, Langen GJ de, Kramer E, Schelvis J (1995/1996) The early medieval cemetery of Oosterbeintum (Friesland). Palaeohistoria 37/38:245–416

Kramer E, Prummel W (1992–1998) Oosterbeintum: voorwerpen van gewei en been. Jaarverslagen Vereniging voor Terpenonderzoek 76–82:98–114

Kuijper WJ (2001) Malacologisch onderzoek naar mariene mollusken uit laat-neolithische vindplaatsen in Noord-Holland. In: Heeringen RM van, Theunissen EM (eds) Kwaliteitsbepalend onderzoek ten behoeve van duurzaam behoud van neolithische terreinen in West-Friesland en de Kop van Noord-Holland. Nederlandse Archeologische Rapporten 21, deel 3. Rijksdienst voor het Oudheidkundig Bodemonderzoek, Amersfoort, pp 333–347

Langen G de, Perger T, Prummel W, Schelvis J, Taayke E, Willemsen J, Wispelwey M (1994) Een korte verkenning te Bolland bij Lions (Fr). Paleo-Aktueel 5:74–79

Leeuwen S van (2003) De land- en zoetwatermollusken van Schiermonnikoog, inventarisatie in het kader van het atlasproject Nederlandse mollusken. Spirula 334:103–108

Ligtvoet W (1992) Noordse woelmuis Microtus oeconomus (Pallas, 1776). In: Broekhuizen S, Hoekstra B, Laar V van, Smeenk C, Thissen JBM (eds) Atlas van de Nederlandse Zoogdieren. KNNV-Uitgeverij, Utrecht, pp 273–280

Lotze HK (2005) Radical changes in the Wadden Sea fauna and flora over the last 2,000 years. Helgol Mar Res (in press)

Maanen G van, Vaandrager F (1988) De faunaresten uit de ringgracht van de middeleeuwse stinswier te Zweins (Frl). Westerheem 37:176–182

Poppe GT, Goto Y (1993) European seashells II (Scaphopoda, Bivalvia, Cephalopoda). Verlag Christa Hemmen, Wiesbaden

Prummel W (1989) Resten van vee, vis en weekdieren uit een 12e-13e-eeuwse terp aan de Dorpen te Schagen. In: Diederik F (ed) Archeologica. De archeologie van het noorden van Noord-Holland in historisch en landschappelijk perspectief. Pirola, Schoorl, pp 148–164

Prummel W (1992) Vlees en vis op de rijk gevulde dis. In: Avest HP ter (ed) Opmerkelijk afval. Vondsten uit een 17de eeuwse beerput in Harlingen. Gemeentemuseum Het Hannemahuis Harlingen, pp 99–111

Prummel W (1997) Evidence of Hawking (Falconry) from Bird and Mammal Bones. Int J Osteoarchaeol 7:333–338

Prummel W (1999) The effects of medieval dike building in the north of the Netherlands on the wild fauna. In: Benecke N (ed) The holocene history of the European vertebrate fauna, Modern aspects of research. Workshop 6–9 April 1998, Berlin. Archäologie in Eurasien 6. Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH, Rahden/Westf, pp 409–422

Prummel W (2001) The significance of animals to the early medieval Frisians in the northern coastal area of the Netherlands: archaeozoological, iconographical, historical and literary evidence. Environ Archaeol 6:73–86

Prummel W, Knol E (2005) Twee soorten kokkels van het wad. Paleo-Aktueel 14 (in press)

Reichstein H (1991) Die Fauna des germanischen Dorfes Feddersen Wierde. Feddersen Wierde 4. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart

Reichstein H (1994) Die Säugetiere und Vögel aus der frühgeschichtlichen Wurt Elisenhof. Studien zur Küstenarchäologie Schleswig-Holsteins Seria A. Elisenhof 6. Peter Lang, Frankfurt/Main, Berlin, Bern, New York, Paris, Wien, pp 1–214

Reijnders PJH (1992) Phoca vitulina Linnaeus 1758 - Seehund. In: Duguy R, Robineau D (eds) Handbuch der Säugetiere Europas 6: Meeressäuger II, Robben - Pinnipedia. Aula Verlag, Wiesbaden, pp 120–137

Reise K (2003) Metapopulation structure in the lagoon cockle Cerastoderma lamarcki in the northern Wadden Sea. Helgol Mar Res 56:252–258

Reitz EJ, Wing ES (1999) Zooarchaeology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Requate H (1956) Die Jagdtiere in den Nahrungsresten einiger frühgeschichtlicher Siedlungen in Schleswig-Holstein. Schriften des Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins für Schleswig-Holstein 28:21–41

Schekkerman H (2002) Kievit Vanellus vanellus. In: SOVON Vogelonderzoek (ed) Atlas van de Nederlandse Broedvogels 1998–2002. Nederlandse Avifauna 5. Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum Naturalis, Leiden, pp 210–211

Schmölcke U (2005) Neue Bemerkungen zu alten Funden—Tierkochen von der Lembecksburg auf Föhr. Offa (in press)

Schmölcke U, Breede M (2005) Eisenzeitliche Tierknochen aus dem Muschelhaufen bei Dunsum/Föhr—Eine Revision alter Funde. Archäologische Nachrichten aus Schleswig-Holstein (in press)

Schneewolf T (1977) Die Schweine- und Wildtierknochenfunde der ältereisenzeitlichen Siedlung Boomborg/Hatzum an der unteren Ems. Realschullehrerarbeit, unpublished, Kiel

Segschneider M (1999) Besiedlung und Fundgut der nordfriesischen Insel Amrum in der älteren römischen Kaiserzeit. Offa 53(1996):137–192

Spratte S (2001) Aussterben des Störes (Acipenser sturio L.) in der Eider. In: Düver W (ed) Der Stör Acipenser sturio L. Fisch des Jahres 2001. Verlag M. Faste, Kassel, pp 66–86

Theunissen EM (2001) Deel 2 Site-Dossiers. In: Heeringen RM van, Theunissen EM (eds) Kwaliteitsbepalend onderzoek ten behoeve van duurzaam behoud van neolithische terreinen in West-Friesland en de Kop van Noord-Holland. Nederlandse Archeologische Rapporten 21 (3 parts). Rijksdienst voor het Oudheidkundig Bodemonderzoek, Amersfoort, pp 1–358

Walhorn A, Heinrich D (1999) Untersuchungen an Tierknochen aus der mittelalterlichen Wurt Niens, Ldkr. Wesermarsch. Probleme der Küstenforschung im südlichen Nordseegebiet 26:209–262

Witt R (2002) Untersuchungen an kaiserzeitlichen und mittelalterlichen Tierknochen aus Wurtensiedlungen der schleswig-holsteinischen Westküstenregion. Dissertation, Kiel

Woltinge I, Prummel W (2005) Wommels-Stapert: botmateriaal uit de vroege ijzertijd en de midden-ijzertijd (Fr). Paleo-Aktueel 14 (in press)

Wymenga E (2002) Grutto Limosa limosa. In: SOVON Vogelonderzoek (ed) Atlas van de Nederlandse Broedvogels 1998–2002. Nederlandse Avifauna 5. Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum Naturalis, Leiden, pp 220–221

Zagwijn WH (1986) Nederland in het Holoceen. Geologie van Nederland, Deel I. Rijks Geologische Dienst, Haarlem / Staatsuitgeverij, ‘s-Gravenhage

Zawatka D, Reichstein H (1977) Untersuchungen an Tierknochenfunden von den römerzeitlichen Siedlungsplätzen Bentumersiel und Jemgumkloster an der unteren Ems/Ostfriesland. Probleme der Küstenforschung im südlichen Nordseegebiet 12:85–128

Zeiler JT (1996) Texelse maaltijden. Faunaresten uit de Oude Schans op Texel (16e–20e eeuw). ArchaeoBone Rapport 6. Groningen

Zeiler JT (1997) Hunting, fowling and stock-breeding at Neolithic sites in the western and central Netherlands. ArchaeoBone, Groningen

Acknowledgements

E. Knol pointed to the presence of C. lamarcki shells in Heveskesklooster and to the publication by Van Leeuwen. H.J. Kühn of the Archäologisches Landesamt Schleswig-Holstein kindly permitted the publication of the data on the aurochs from the Wadden Sea west of Hamburger Hallig. K.L.B. Bosma kindly permitted the publication of unpublished bird bone identifications from Wijnaldum-Tjitsma.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by H.K. Lotze and K. Reise

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Prummel, W., Heinrich, D. Archaeological evidence of former occurrence and changes in fishes, amphibians, birds, mammals and molluscs in the Wadden Sea area. Helgol Mar Res 59, 55–70 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-004-0207-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-004-0207-1