Abstract

The Helgoland Roads meso- and macrozooplankton time-series 1974 to 2004 is a high frequency (every Monday, Wednesday and Friday), fixed position monitoring and research programme. The distance to the coastline reduces terrestrial and anthropological disturbances and permits the use of Helgoland Roads data as indicators of the surrounding German Bight plankton populations. The sampling, determination and IT methodologies are given, as well as examples of annual succession, and inter-annual population dynamics of resident and immigrant populations. Special attention is given to the phenology and seasonality of zooplankton populations. The influence of winter sea surface temperature on the seasonality of spawning of the common sole Solea solea is given as an example for merozooplankton populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A single observation of nature permits the definition of the momentary state. Repeated observations in space or time permit the recognition of distributional rules and variances. Local repetitions of observations produce time-series as a documentation of the system dynamics. Time-series enable the development of analytical models defining state variables and rates of processes, and testing hypothetical rules of change. The definition of the rules, and variances determining abundance distributions of populations and their changes, are the main subjects in ecosystem research. The degree of the understanding of such processes is expressed in analytical and operative models predicting changes in abundance distributions. The rules of change concern physicochemical forcing, physiological response mechanisms and trophodynamic processes. Significant time-scales can cover several orders of magnitude. Therefore, causal time-series analysis has to rely on data sets from various sources. While experimental time-series may operate informatively on less complex systems (e.g. Greve 1995a), in situ time-series are real and their documentation and analysis are most important (Perry et al. 2004). The Helgoland Roads station enables the continuous monitoring of marine processes in an offshore location with little terrestrial and anthropogenic disturbance and, due to the Biologische Anstalt Helgoland, affordable sampling capacity is available.

Methods

The Helgoland Roads time-series on meso- and macrozooplankton was started in 1974 as a spin-off data collection stemming from the daily live-food catches from the small cutters of the Biologische Anstalt Helgoland (BAH) marine station. These zooplankton samples were provided to the laboratory for cultivation experiments and for eventual observation. Phytoplankton and nutrients had been measured every work day since 1962 (Hickel et al. 1993); the expected availability of this information, the then dominant bottom-up theory and the measurement of meso- and macrozooplankton led to the expectation that even in a hydrographically complex locality the trophic controls of zooplankton population abundance and distribution might become evident. The aim was the production of time-series which would permit the testing of simulation models on the trophodynamics of the pelagic ecosystem then believed to be the decisive mechanism for population control. The basis of the intended modelling in those days was a conceptual model of the IBP type (Greve 1972).

Sampling, preservation, sorting and counting

The plankton nets commonly used for the sampling of zooplankton on the small cutter “Ellenbogen” until April 1974 were not equipped with a counter to measure the volume filtered, nor with a conical design that avoided escape responses of zooplankton approaching the net. These nets were replaced by the HYDROBIOS quantitative collection device 438040 (150 μm hand-net, aperture 17 cm, net length 100 cm, FlowMeter, ballast weight) and the HYDROBIOS ring trawl net 438700 (Calcofi Net; mesh size 500 μm, 100 cm aperture, length 400 cm, depressor and FlowMeter). Both nets were used for oblique hauls under the prevailing conditions of Helgoland Roads, generally not permitting vertical hauls due to a depth of only 6 to 8 m.

Sampling was generally carried out at the position 54°11′18″N 7°54′ E) during morning hours, thereby shifting the sampling by 45 min daily through the tidal cycle. Samples were live-counted until 1981 on a daily basis. In 1982, sampling was reduced to Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. Samples are preserved in 4% formaldehyde. As some species (e.g. Bolinopsis infundibulum) cannot be preserved, occasional live counts were continued for limited time-periods on the basis of plane transports from Helgoland to Hamburg.

The taxonomic and numeric biodiversity was investigated and documented to the earliest possible date, handling meso- and macrozooplankton separately. While mesozooplankton was determined by F. Reiners and W. Greve only, macrozooplankton was determined by W. Greve, J. Nast, S. Hoffmann and various other assistants and students. The list of species and stages counted varied with taxonomic changes and increasing professional expertise. Fish larvae which were at first intentionally excluded from taxonomic analysis due to the institutional organisation, were determined and counted for 7 years from 1990.

Metazoa continuously change their characteristics with growth. Fixation does not preserve the pigments of fish larvae; they become bleached. Therefore, the taxonomic treatment of the complete size class, especially of macrozooplankton, requires expertise that can only be obtained after a long training period. Though this training could be supported by the experiences gained, individual inconsistencies cannot be excluded.

The training was supported by selected literature (e.g. Sars 1903; Zimmer 1909; Grimpe 1911–1942; Pesta 1928; Russell 1953, 1970, 1976; Williamson 1957; Kermack 1966ff; Jones 1976; Pierrot-Bults and Chidgey 1988; Ingle 1992), photographs and drawings, samples from the sorting exercises and a collection of reference samples.

The plankton was sub-sampled according to the number of organisms present. An aliquot of 60 individuals of each key species was regarded as an acceptable threshold level. Determination and counting were carried out in counting chambers using microscopes.

Coverage of the time-period sampled

The aim was to operate the investigation at the highest possible frequency. This was possible on a daily basis (weekdays) until 1981, then the sampling frequency had to be reduced to Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. Mesozooplankton sample analysis could be maintained at this frequency. For macrozooplankton, the taxonomic range was extended to ichthyoplankton in the 1990s. This taxonomic expansion of the analyses had to be countered by a reduction in the number of samples analysed to one sample per week. Due to organisational changes within the institutions involved, the macrozooplankton samples lag behind the mesozooplankton analysis.

Computation

The sorting and counting protocols are transferred into electronic storage via computer programs written in Visual Basic under Excel. Individuals m−3 are calculated as the standard value. Control programs check the plausibility of data with respect to value limits, parameter names and double entries.

Additional external information on weather, physical parameters, nutrients and phytoplankton is available as ASCII files in a comparable format from various sources [e.g. DWD (German Weather Service), BAH/AWI, BSH (Federal Marine and Hydrographic Agency of Germany)].

Macro programs enable the comparison of current parameter values with a 20 years’ standard mean in visualisation and in ranking according to the variation of parameters, including abundance and phenology (start of season, middle of season, end of season and length of season) on the basis of calculated annual cumulated sums (Table 1).

Prognoses

The internet site http://www.senckenberg.de/dzmb/plankton gives further information on the research strategy, methodology and current results of the operative plankton prognoses. Since April 2004, a phenological prognosis is given for 50 populations. Based on the available time-series, the prognoses are recalculated automatically every day for each population. The automated phenological analysis calculates phenological predictions for every week according to the available abundance and temperature records, and chooses the week with the minimal deviation from that recorded during recent years for the current prognoses. The predictions span periods of up to 6 months. The error of the calculations is given as absolute times and as a percentage of the total observed phenophase period.

Auxiliary calculations: advection

Plankton advection occurs in three dimensions at variable orders of magnitude according to the tidal phase, and climate- and weather-driven currents. In order to be able to calculate this influence on the daily plankton catches, a simulation model was used. This model, of the “drawer type”, operates on the basis of former calculations of the operative advection model from BSH, from which the current conditions were extracted for the main wind directions and forces at Helgoland after a period of 3 days of continuous, almost identical, wind conditions. These values can then be used as approximations to the values to be calculated in the BSH operative advection model. While this model requires a broad input of climate data, computer capacity and time, the drawer model can easily be run for any period for which wind conditions at Helgoland are available from the German Weather Service (DWD). The drawer model DRIFT (Reiners, Müller-Navarra and Greve, unpublished data) is available as a GFA-Basic program from the authors.

The model permits the forward and backward calculation of advective transport in the German Bight for any period of time for the visualisation of local trajectories or for the calculation of the advective patterns. A 14-day backwards calculation for every day of the year, whereby 1987 was chosen as an example for the mean distribution of the origin of the plankton sampled at Helgoland Roads, is shown in Fig. 1.

Mean origin of the water masses sampled at Helgoland Roads. Fourteen-day backwards trajectory calculations of 100 particles sampled daily from 1975 to 2003 are displayed as percentage distributed over 36 simulated boxes of the German Bight (drawer model DRIFT: Reiners, Greve, Müller Navarra, unpublished data)

Publications (papers, MURSYS, BLMP reports)

The results of the Helgoland Roads meso- and macrozooplankton analyses are partially published in the current “marine Umwelt reporting System MURSYS” from BSH as part of the national environmental monitoring programme. Reports of the Bund Länder Meßprogramm (BLMP) are available in regularly updated current versions on the internet, and as a printed version (e.g. BSH 2002). The Helgoland Roads zooplankton collection is also reported in the ICES WG Zooplankton Ecology (Valdez 2001).

A bibliography of the main results includes the following publications: Greve (1992, 1994, 1995a, 1995b); Greve and Reiners (1980, 1988, 1995, 1996); Greve et al. (1996, 2001); and Lange and Greve (1997).

Results

In the 30 years samples have been taken at Helgoland Roads, 443 taxonomic entities have been determined (Table 1), counted and calculated for standardised electronic storage. Due to the long time period, the high taxonomic resolution and the high sampling frequency, a unique data pool exists. As the catching method permits the identification of gelatinous zooplankton as well as crustacean plankton and fish larvae, the description and analysis of interacting populations is possible with only the restrictions of single point sampling.

The information thus obtained includes measurements on the abundance, the change of abundance on timescales of days to decades and the variance of these changes for the major zooplankton species, representing the biodiversity of the meso- and macrozooplankton, including the ichthyoplankton, in the waters of the German Bight. These changes reveal distributions and response patterns which help the understanding of the marine ecosystem. Some of these aspects are exemplified here.

The composition of the mesozooplankton in the shelf sea near Helgoland is primarily determined by holoplanktonic populations, but for some periods meroplankton is more abundant in the mesozooplankton.

The macrozooplankton includes hydro- and laval scyphomedusae, decapod and fish larvae in quantities which can be larger than the abundance of ctenophores, chaetognaths, the large copepod Calanus helgolandicus, and mysids to mention the major groups. So the shelf sea macrozooplankton is influenced by meroplankton to a great extent.

Holo-zooplankton of the meso- and macrozooplankton size classes is composed of a rich variety of species, standing for diverse functional units. These represent omnivory with a preference for herbivory of selected size classes (e.g. Calanus helgolandicus feeding on larger particles and Oikopleura dioica feeding on small particles), omnivory with a preference for carnivory (e.g. Oithona helgolandica), omnivory with a preference for detritivory (e.g. Euterpina acutifrons), and primary carnivory (e.g. Pleurobrachia pileus) or secondary carnivory (e.g. Beroe gracilis).

Variance of zooplankton measurements

Zooplankton abundance and distribution varies under the influence of ethology (e.g. patchiness, diurnal vertical migration), physical forcing (advection, temperature dynamics), and physiological (e.g. temperature responses) and ecological conditions (e.g. trophodynamics, ontogeny) on any time and space scale with up to several orders of magnitude difference. The interpretation of the measurements obtained under these conditions must consider this variance, which can partially be countered by a high sampling frequency, long oblique plankton hauls sub-sampled successively and the calculation of the results (e.g. averaging).

Annual dynamics

The “plankton bloom”, the abundance increase of the phytoplankton population is commonly understood as the start of the annual cycle of trophic succession in the temperate zone. This includes “bottom-up” elements of production stimulating consumption and “top-down” elements as the reduction of food resources by grazing or predation. These interactions can be seen in the sequence of four trophically linked populations in Fig. 2. The phytoplankton grows in weeks 16 to 21, followed by a drastic reduction in weeks 22 to 25; this corresponds to the drastic population increase of small calanoid copepods in weeks 21 to 23. The populations then collapse in weeks 24 and 25 while the ctenophore Pleurobrachia pileus increases in abundance from 5 to 70 individuals m−3. P. pileus is a voracious copepod predator (Greve 1970). Within 7 weeks, the system dominance is shifted from the phytoplankton to the secondary carnivore. With the reduction in herbivorous copepods, the phytoplankton starts a second bloom period. The tentaculate ctenophore population is then reduced within 3 weeks by the population of beroids, mainly Beroe gracilis. The specialised P. pileus predator increases in abundance. With the release of the predation pressure on copepods, these can propagate again to a second population maximum in week 32; again the phytoplankton populations collapse. This example demonstrates the synchronous functionality of bottom-up and top-down control as characteristic of prey-predator cycles (Greve and Reiners 1988). This example is not a causal analysis of the complete 1987 population dynamics, as many more populations are part of the trophodynamic ecosystem regulation, and nor does it neglect the possible influences of, for example, advection. Furthermore, 1 year cannot be used as a prototype of trophodynamics for many years. Averaging the annual dynamics tends to extinguish the trophic responses, as short time differences from year to year may lead to a contradictory temporal orientation.

Annual zooplankton dynamics are characterised by the seasonal succession of populations characterising trophic functional relationships between functional groups or populations (Greve and Reiners 1988). Key species may dominate for restricted periods. Besides autecological functional discrimination, biocoenotic separation of seasonal communities is possible (Greve and Reiners 1995) indicating successive functional ecosystem equilibria.

Not all sequential events are based on trophic interactions and succession. Advection and migration also leads to a sequence of events that influences the local time-series measurements.

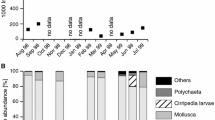

This is of reduced importance in the succession of more general functional groups, as in copepods which exemplify the functional biodiversity of zooplankton (seasonal mean 1975–2002). Calanoida represent herbivorous to omnivorous zooplankton: Paracalanus spp. + Pseudocalanus spp., Centropages typicus + C. hamatus, Temora logicornis , Acartia spp.. Cyclopoida represent carnivorous to omnivorous zooplankton: Oithona spp., Cyclopina spp., Corycaeus spp.. Harpacticoida represent detritivorous to omnivorous zooplankton: Euterpina acutifrons, Tisbe spp., Microsetella spp. (Fig. 3). Over the course of the year, the herbivorous to omnivorous calanoids are succeeded by the carnivorous to omnivorous cyclopoids and then by the detritivorous to omnivorous harpacticoids. This functional pattern corresponds to the seasonality of the more herbivorous appendicularians and larvae of echinoderms and polychaetes, the carnivorous decapod larvae and the partially detritivorous mysids. However, there are many exceptions from this scheme.

Inter-annual dynamics

The annual zooplankton succession varies considerably from year to year with respect to the seasonality and the abundance of single populations. In some cases, these changes represent a trend over a few or many years. Four examples are given for such behaviour:

The copepod fauna of the German Bight is dominated by small calanoid populations of the species Pseudocalanus elongatus, Paracalanus spp., Centropages typicus + C. hamatus, Temora logicornis and Acartia spp. The sum of the abundance of these populations renders a basic pattern of changes in the pelagic ecosystem. These changes occur in the total abundance per year and in the annual distribution (Fig. 4a). As only a coarse description and analysis is given here, the increase in the summer abundance of calanoid copepods in the mid 1980s to 1990s is mentioned. With increased summer abundance, the season expands into the spring and autumn months. With the decrease in annual abundance in recent years, the season is shortened towards the spring and summer months. The abundance peak in the 1980s corresponds with the phytoplankton maxima in these years which are thought to have been related to eutrophication (Hickel et al. 1993). See also Wiltshire and Dürselen.

Abundance distribution (monthly means 1975–2002) of small calanoid copepods ( a), juvenile Pleurobrachia pileus ( b), Alaurina composita ( c) and Penilia avirostris ( d) exemplifying shifts in the annual abundance ( a), seasonal expansion ( b), dominance changes within the fauna ( c) and neozoan immigration ( d)

In the case of the ctenophore Pleurobrachia pileus, measurements are available for 14 developmental stages, of which the newly hatched juveniles are measured in the merozooplankton samples which haven been analysed for the complete period of 27 years. Fig. 4b demonstrates, in agreement with the measurements of adult specimens, a basic change in annual distribution starting in 1988 and continuing in the years after. In the years to 1977 an abundance maximum was observed in June, this peak abundance then expanded into spring and autumn. The abundance maximum first gets reduced and distributed over almost the whole year, followed by a period of earlier population growth. This corresponds to the observation of the response of the seasonality of P. pileus to increased winter temperatures (Greve et al. 2001) and to the change in the distribution patterns observed in North Sea plankton (Reid and Edwards 2001).

Another drastic change in the abundance and distribution of zooplankton was monitored in the case of the turbellarian Alaurina composita which, according to our observations and to related limnetic populations, is a voracious predator on copepods and cadocerans. This species is hardly taken into account in ecosystem investigations, though one individual may eat four copepods per day. Until the early 1980s, 2 to 4 individuals m−3 were occasionally registered in the summer months: suddenly in the mid 1980s the abundance increased by four orders of magnitude. Abundances of up to 5,000 individuals m−3 were recorded. In the following years, the abundance decreased again by one to two orders of magnitude (Greve and Reiners 1996). The higher abundance level prevailed until 2002 (Fig. 4c).

The final example for faunal changes in the zooplankton is the immigration of the neozoon Penilia avirostris. This cladoceran is a Mediterranean and subtropical species. It was first observed as a few specimens in the winter of 1991. Since then it has reappeared irregularly with increasing abundance and length of season (Fig. 4d).

The observation of faunal changes is an important service of the Helgoland Roads time series. This does not concern only neozoa, but also the loss of populations. Table 2 exemplifies this for the population of the appendicularian Fritillaria borealis which was missing in 1999 and only caught in one sample in 2001. This species is known to be important as food for fish larvae. It may be close to its southern distributional limit. The development of the abundances of the neozoans Muggiaea alantica, Doliolum nationalis and Penilia avirostris are also included in Table 2.

Phenological trends

The ambient temperature permanently controls the physiology of marine organisms. This control concerns e.g. the digestive system, the ontogeny and the development of gonads (Lange and Greve 1997). One of the processes in which such a control becomes visible is the seasonal timing of populations (Greve et al. 2001).

Phenological information offers two options for the recognition of the functional response of populations to the sea surface temperature (SST) and the prediction of the seasonality on this basis and, further, the observation of the long-term changes enables the recognition of temporal population responses to climatic forcing. Such forcing generally relates rising temperatures with phenophases at an earlier time. The responses and trends are species-specific (Figs. 5, 6). In the case of the genus Evadne (species were not determined), even the sum of the species displays an obvious temperature response. The temperature increase in the winter months at Helgoland corresponds with precession of the phenophase “middle of season” (time of the passage of 50% of the annual cumulative abundance threshold). The correspondence of the phenological trend with the trend in temperature change can be understood by the functional relationship of Evadne to SST (Fig. 6). Winter temperatures of 0–6°C have been observed which were correlated with time shifts of 6 weeks for the phenophase “middle of season”. This functional relationship forms a basis for future prognoses, as weeks 1 to 10, from which the temperatures were derived, precedes the middle of season of Evadne by a minimum of 3 months.

Observation- and functionality-based prognoses represent two ways to understand the decisive role of phenology in marine ecology (Greve 2003).

The prediction of population dynamics is one aim of ecological research. The temporal prognosis based on the phenology of zooplankton was attempted on the basis of the Helgoland Roads time series (Greve et al. 2001). Regressions of temperatures with phenophases result in correlation coefficients of up to r 2=0.8. This stands for a dominant population control, compared to the temporal influence of trophic relationships. The abundance, however, remains to be predicted. The match/mismatch analyses may contribute to this prognosis.

The operative prognoses for 50 taxonomic entities from the Helgoland Roads zooplankton was started on 5 April 2004 after the completion of the thirtieth year of this time-series (Fig. 7). The intention is to expand this to further populations and introduce quantitative information.

Discussion

Unbiased observation of nature is almost impossible, as our scientific education includes learning and shaping. The shape we get is expressed in paradigms, according to which we design our investigations. The design of our studies can determine the outcome, the result, which is thus self-fulfilling and thus conserves our bias. As no reliable paradigm was available at the start of the measurements of the Helgoland Roads time-series, this project was started as a very general programme monitoring the possibly important zooplankton populations which might be required for future prognostic models. The resulting database enabled the description and spatial analysis of many specific processes, and the development of simulation and statistical models, which led to operative prognoses of the temporal distribution of the regional zooplankton populations. In the advancement of operative models, the data provide a permanent source of information.

The Helgoland Roads zooplankton time-series is biodiversity based. The species-specific changes in distribution and abundance—in some cases even the differences in developmental states—can be studied, specifically analysed or aggregated according to the investigated hypothesis. These aggregations can always be reduced again to single population dynamics for detailed analysis.

Shelf sea zooplankton is characterised by the influence of meroplankton, which is of increasing importance with increasing size of the organisms. Merozooplankton consists of the pelagic generation of coelenterates and the larval stages of zoobenthos and nekton. In this ontogenetic stage, the rate of annual recruitment is determined for many benthic and nektonic populations during the planktonic state, as the abundance and timing of the eggs and larvae is determined by the nutritional and physiological state of the parental generation. This bentho-pelagic coupling is especially great in shelf seas and contradicts any attempt to understand the benthic and the pelagic systems separately.

Zooplankton survival depends on the availability of primary production (bottom-up control) and on the presence or absence of the population-specific predators (top-down control). The annual development of these trophic controls was weighed by Greve and Reiners (1995).

An example of annual trophic control is given for 1987: it is not a causal analysis of the complete population dynamics in this year, as many more populations are part of the trophodynamic ecosystem regulation, and nor does it neglect the possible influences of e.g. advection. However, the comparison of Helgoland Roads dynamics with regional dynamics in the German Bight suggests that the local time-series can be regarded as an indicator of the regional population dynamics (Greve and Reiners 1988). This report described the local succession of trophic controls as the expression of population waves travelling from the coast to the central German Bight. Sequence and succession appears in the form of three-dimensional regional processes (Greve and Reiners 1980, 1988). The influence of regional temperature differences and advection remains to be analysed.

One year cannot be taken for a prototype of regional trophodynamics for many years. Averaging the annual dynamics tends to extinguish the trophic responses, as short time differences from year to year may lead to a contradictory temporal orientation.

In situ measurements provide important indicators and controls for ecosystem causal analysis, but only laboratory experiments and controlled ecosystem process studies linked by a theory in a common model will enable understanding of such complex process dynamics (Greve 1992).

A unifying concept of population control

Population prognosis is the final test of hypotheses, models and paradigms. The measurement of the skill of such prognoses requires the availability of independent time-series which were not used for the development of the model. The Helgoland Roads zooplankton time-series provide such data.

The numeric variance of zooplankton based on generation times, trophodynamics, advection, physiology and ambient temperatures must be understood for controlled ecosystem management.

The causal hypotheses derived from the ecosystem analysis can be tested in operational prognostic models which can be used continuously to disprove hypotheses and to improve them. The improvement of the prognostic skill must be of focal importance (Greve 1995b).

A first operative prognosis of Helgoland Roads zooplankton populations is available under www.senckenberg.de/dzmb/plankton. It operates on the basis of the phenology of zooplankton, which is mainly based on preceding temperatures (Greve et al. 2001). This statistical relationship is poorly understood as a functional causal relationship. The physiological requirements of zooplankton concern temperature and salinity. Each population has specific preference profiles for both parameters, as measured for Noctiluca scintillans (Uhlig and Sahling 1995). As these measurements are lacking for most zooplankton, the profiles can be determined in a first approximation by relating the annual abundance measurements and the distributional information to the ambient temperatures and salinities. In the appendicularians Fritillaria borealis and Oikopleura dioica, a temperature profile with an optimum value of 12°C for F. borealis and 14°C for O. dioica enabled the simulation of the seasonal variance of the two species with the extended niche model (Greve 1995b). These values were extracted from the Helgoland Roads time-series.

The potential of climatic influences on the distribution of zooplankton was shown by Southward et al. (1995) who registered a lateral displacement of populations, and by Greve et al. (1996) who detected a shift in the seasonal timing of zooplankton.

It is surprising that phenology, a well-established science in terrestrial ecology, has not made it into the aquatic sciences earlier (Greve 2003). Climate change requires extended phenological research in marine ecosystems. Recent global warming has led to phenological changes which it has been possible to observe in terrestrial systems (Menzel 2000). Phenological responses have also been observed in neritic copepods (Kioerboe et al. 1988). Recent observations of lateral shifts of zooplankton (Southward et al. 1995) and algae (Molenaar and Breeman 1997) prove that changes in the marine biota based on climatic alterations are already underway. Marine biometeorology should be further developed by observing the phenology of marine zooplankton over a wider range of latitudes than just Helgoland Roads.

Recent extensions of the seasonality investigation have revealed that many fish larvae can be predicted as the makro- and mesozooplankton (Fig. 8). The economic importance of marine fish, and the available theory (Cushing 1990) on the match/mismatch of spawning for successful recruiting, will stress the importance of high-frequency zooplankton sampling over further latitudes.

Functional relationship between the timing of the annual phenophase “middle of season” of sole ( Solea solea) and the preceding winter temperature (1990, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1998 and 1999). The resulting regression enables prognoses of the annual seasonality, from Grere et al., personal communication

The extensive multi-decade CPR plankton collection over the North Atlantic by the Alister Hardy Foundation for Ocean Sciences (SAHFOS), which enabled the recognition of faunal changes (Beaugrand et al. 2002), can be supplemented with such series, leading to the causal analysis of such changes. They can both contribute to anticipating changes in the pelagic plankton in the coming period of biocoenotic responses to global warming. The high frequency Helgoland Roads time-series permits the measurement of the regression analysis of temperature and phenology. Gelatinous plankton, which is only marginally represented in the CPR programme, is sampled and determined at Helgoland Roads and thus available for food web analysis.

Changes in the ecosystem due to new species immigrating and the loss of others which can no longer exist in the southeast North Sea in future warmer years can best be realised and valued in a time-series which can compare the present and the future with the documented past. Helgoland Roads is a permanent watch station for such changes which might otherwise alter the ecosystem without being recognised (e.g. Greve 1994).

The Helgoland Roads time-series on meso- and macrozooplankton is unique with respect to its length, sampling frequency, biocoenotic resolution (including the gelatinous populations) and the size spectrum of organisms investigated. The insight into the dynamics of the pelagic ecosystem obtained has revealed trophic control mechanisms, the relevance of these to the ecosystem, and the influence of temperatures from much earlier on the seasonality of zooplankton, including many benthic and nektonic populations. Thereby, high frequency zooplankton sampling has proven its importance for bentho-pelagic coupling and general marine ecosystem analysis.

Ecosystem management is based on our understanding of the ecosystems. The available knowledge will be converted into models (simulations and statistical models). Permanent operative prognoses, as started this year, will help to detect weaknesses in our understanding, leading to investigations and improvements to our operative models. Decisions will be optimised based on continuous observations of environmental indicators. This time-series could provide a further basis for such ecosystem management support.

References

Beaugrand G, Reid PC, Ibanez F, Lindley JA, Edwards M (2002) Reorganisation of North Atlantic marine copepod biodiversity and climate. Science 296:1692–1694

BSH (2002) Meeresumwelt 1997–1998. Hamburg and Rostock: Bundesamt für Seeschiffahrt und Hydrographie (BSH).

Cushing DH (1990) Plankton production and year-class strength in fish populations: an update of the match/mismatch hypothesis. Adv Mar Biol 26:249–293

Greve W (1970) Cultivation experiments on North Sea Ctenophores. Helgol Wiss Meeresunters 20:304–317

Greve W (1972) Ökologische Untersuchungen an Pleurobrachia pileus. 2. Laboruntersuchungen. Helgol Wiss Meeresunters 23:370–374

Greve W (1992) Die Bedeutung synthetischer Ökosysteme für die marine Systemökologie. Rundbrief der Transferstelle für Meerestechnik, Bremen 12:12–17

Greve W (1994) The 1989 German Bight invasion of Muggiaea atlantica. ICES J Mar Sci 51:355–358

Greve W (1995a) Mutual predation causes bifurcations in pelagic ecosystems: the simulation model PLITCH (PLanktonic swITCH), experimental tests and theory. ICES J Mar Sci 52:505–510

Greve W (1995b) The potential of and limitations to marine population prognosis. Helgol Wiss Meeresunters 49:811–820

Greve W (2003) Aquatic plants and animals. In: Schwartz (ed) Phenology: an integrative environmental science. Kluwer, Netherlands, pp 385–403

Greve W, Reiners F (1980) The impact of prey-predator waves from estuaries on the planktonic marine ecosystem. In Kennedy VS (ed) Estuarine perspectives. Academic Press, New York, pp 405–421

Greve W, Reiners F (1988) Plankton time-space dynamics in German Bight—a system approach. Oecologia 77:487–496

Greve W, Reiners F (1995) Biocoenotic process patterns in German Bight. In: Eleftheriou A, Ansell A, Smith CJ (eds) Biology and ecology of shallow coastal waters. Olsen and Olsen, Fredensborg, Denmark, pp 67–71

Greve W, Reiners F (1996) A multiannual outbreak of the turbellarian Alaurina composita Mecznikow 1865 in the North Sea. J Plankton Res 18:157–162

Greve W, Reiners F, Nast J (1996) Biocoenotic changes of the zooplankton in German Bight: the possible effects of eutrophication and climate. ICES J Mar Sci 53:951–956

Greve W, Lange U, Reiners F, Nast J (2001) Predicting the seasonality of North Sea zooplankton. In: Kröncke I, Türkay M, Sündermann J (eds) Burning issues of North Sea ecology, Proceedings of the 14th International Senckenberg Conference North Sea 2000. Senckenb Marit 31:263–268

Grimpe GWE (1911–1942) Die Tierwelt der Nord- und Ostsee und der angrenzenden Meeresteile nach ihren Merkmalen und nach ihrer Lebensweise. Fischer, Jena

Hickel W, Mangelsdorf P, Berg J (1993) The human impact on the German Bight: eutrophication during three decades 1962–1991. Helgol Meeresunters 47:243–263

Ingle R (1992) Larval stages of northeastern Atlantic crabs. Chapman and Hall Identification Guides 1

Jones NS (1976) British cumaceans, Arthropoda: Crustacea. Keys and notes for the identification of the species. Academic Press, London

Kermack DMRSKB (ed) (1966ff) Synopsis of the British fauna, vol 1–38

Kioerboe T, Moehlenberg F, Tiselius P (1988) Propagation of planktonic copepods: production and mortality of eggs.

Lange U, Greve W (1997) Does temperature influence the spawning time, recruitment and distribution of flatfish via its influence on the rate of gonadal maturation? Dtsch Hydrogr Z 49:251–263

Menzel A (2000) Trends in phenological phases in Europe between 1951 and 1996. Int J Biometeorol 44:76–81

Molenaar FJ, Breeman AM (1997) Latitudinal trends in the growth and reproductive seasonality of Delesseria sanguinea, Membranoptera alata , and Phycodrys rubens (Rhodophyta). J Phycol 33:330–343

Perry RI, Batchelder HP, David LM, Chiba S, Durbin E, Greve W, Verheye AHS (2004) Identifying global synchronies in marine zooplankton populations: issues and opportunities. ICES J Mar Sci 61:445–456

Pesta O (1928) Ruderfüßler oder Copepoda. Die Tierwelt Deutschlands und der angrenzenden Meeresteile nach ihren Merkmalen und nach ihrer Lebensweise, vol 9. Krebstier oder Crustacea

Pierrot-Bults, Chidgey KC (1988) Chaetognatha. In: Barnes KDMRSK (ed) Synopsis of the British fauna. Bath Press, UK

Reid PC, Edwards M (2001) Long term changes in the pelagos, benthos and fisheries of the North Sea. Senckenb Marit 321:107–115

Russell FS (1953) The medusae of the British Isles. Anthomedusae, Leptomedusae, Limnomedusae, Trachymedusae and Narcomedusae. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Russell FS (1970) The medusae of the British Isles. II. Pelagic scyphozoa with a supplement to the first volume on Hydromedusae. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Russell FS (1976) The eggs and planktonic stages of British marine fishes. Academic Press, London

Sars GO (1903) An account of the Crustacea of Norway: Copepoda Calanoidea, vol. IV. Alb. Cammermeyer, Christiania

Southward AJ, Hawkins SJ, Burrows MT (1995) Seventy years observations of changes in distribution and abundance of zooplankton and intertidal organisms in the western English Channel in relation to rising sea temperature. J Therm Biol 1–2:127–155

Uhlig G, Sahling G (1995) Noctiluca scintillans: Zeitliche Verteilung bei Helgoland und räumliche Verbreitung in der Deutschen Bucht (Langzeitreihen 1970–1993). Ber Biol Anstalt Helgol 9:1–127

Valdez L (2001) Zooplankton monitoring results in the ICES area. ICES, pp 1–20

Williamson DI (1957) Crustacea, Decapoda: larvae. I. General. Fiches d’indentification du plancton, vol 67

Zimmer C (1909) Die nordischen Schizopoden. In: Nordisches Plankton, Zoologischer Teil, vol 3. Lipsius and Tischer, Kiel

Acknowledgements

This investigation was made possible by the Biologische Anstalt Helgoland, the Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg and the Bundesamt für Seeschiffahrt und Hydrography. It was supported by the captains and crews of the cutters “Ellenbogen”, “Aade”, “Diker”, “Uthörn I”, “Uthörn II”, “Friedrich Heincke” and “Heincke”, by the staff of the marine station preserving, packing and shipping the samples to Hamburg, by many assistants and students who dealt with the lab-work sorting and counting the samples, and putting the results onto electronic media. Uwe Lange, Christian Reick, Silke Johannsen, Peter Johanssen, Michael Jacobsen and the co-operation partners from Hamburg University, Prof. J.O. Backhaus and Prof. B. Page supported the analysis of the Helgoland Roads zooplankton in the BMBF project BEO 03F0223. K.H. Wiltshire initiated this collection of Helgoland Roads times-series reports. We thank all of those mentioned for their contribution to the success of the Helgoland Roads zooplankton time-series.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by K. Wiltshire

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Greve, W., Reiners, F., Nast, J. et al. Helgoland Roads meso- and macrozooplankton time-series 1974 to 2004: lessons from 30 years of single spot, high frequency sampling at the only off-shore island of the North Sea. Helgol Mar Res 58, 274–288 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-004-0191-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-004-0191-5