Abstract

Intramedullary schwannomas (IMS) represent exceptional rare pathologies. They commonly present as solitary lesions; only five cases of multiple IMS have been described so far. Here, we report the sixth case of a woman with multiple IMS. Additionally, we performed the first complete systematic review of the literature for all cases reporting IMS. We performed a systematic review of the literature in PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled (CENTRAL) to retrieve all relevant studies and case reports on IMS. In a second step, we analysed all reported studies with respect to additional cases, which were not identified through the database search. Studies published in other languages than English were included. One hundred nineteen studies including 165 reported cases were included. In only five cases, the patients harboured more than one IMS. Gender ratio showed a ratio of nearly 3:2 (male:female); mean age of disease presentation was 40.2 years; 11 patients suffered from neurofibromatosis (NF) type 1 or 2 (6.6%). IMS are rare. Our first systematic review on this pathology revealed 166 cases, including the here reported case of multiple IMS. Our review offers a basis for further investigation on this disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Within the group of central nervous system tumours, spinal tumours represent a minor fraction of 15% of all cases [1]. Spinal schwannomas represent about 10% of all spinal tumours [1]. Schwannomas occur most frequently within the intradural-extramedullary compartment [1]. The intramedullary location of schwannomas is a rare condition (0.3–1.5%) [2,3,4]. Furthermore, they commonly present as solitary lesions. To date, only five cases of multiple intramedullary schwannomas (IMS) have been described [5,6,7,8,9].

Here, we report a 6th case of a female patient with histologically proven IMS of the cervical spinal cord and an additional small lumbar localized lesion. Additionally, we performed the first complete systematic review of the literature searching PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) for all cases reporting IMS.

Case report

A 53-year-old woman presented with a 4-month history of progressive sensory deficits of the upper and lower limbs, without any further neurological symptoms. There were no neurofibromatosis (NF) stigmas and no history of genetic disorders or spinal injury.

Clinical presentation

Neurological examination revealed hypaesthesia of the first three fingers of the right hand, the right lateral lower leg and the right lateral foot edge. There was no paresis of the upper and lower limbs; the muscular tension was normal. The muscle stretch reflexes were normal and symmetrical. No pyramidal tract signs were present, nor spinal ataxia. The patient was defined as grade I according to the modified McCormick scale [10, 11].

Imaging findings and additional diagnostics

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neurocranium and the cervical spine revealed a 9.3 × 19 mm intramedullary lesion at the level of C2/3, which was isointense on T1-weighted and had both hypo- and hyperintense components on T2-weighted images. The lesion showed intense heterogenous contrast enhancement and caused a massive perilesional spinal cord edema extending from the medulla oblongata to the level of C6 (Fig. 1).

a–c Preoperative MRI of the cervical spine in sagittal (a, b) and transverse (c) slides. T2-weighted images show a hypo- and hyperintense intramedullary lesion at the level of C2/3 (a). T1-weighted images show a heterogeneous gadolinium-enhanced tumour in the sagittal (b) and transverse (c) slides. d–f Preoperative MRI of the lumbar spine in sagittal (d, e) and transverse (f) slides. T2-weighted images show a hypointense lesion at the level of L2/3 (d). T1-weighted images show a homogenous gadolinium-enhanced tumour in the sagittal (e) and transverse (f) slides. g–i Postoperative MRI of the cervical spine in sagittal (g, h) and transverse (i) slides confirming the complete tumour resection

Combining the MRI findings and the neurological examination, we considered a preliminary diagnosis of intramedullary ependymoma. As a consequence, further investigations including a holospinal MRI and a lumbar puncture were carried out to examine the possible presence of drop metastasis. The holospinal MRI revealed a second small (3.4 × 4 mm) lesion at the level of L2/3. The lesion was isointense on T1-weighted and hypointense in T2-weighted images with homogenous contrast enhancement (Fig. 1). Cerebrospinal fluid examination showed no evidence of atypical, potentially malignant cells.

Operative findings and histopathology

The patient underwent uneventful microsurgical tumour resection through a posterior cervical approach and midline myelotomy with subsequent C2–C3 laminoplasty. Intraoperatively, the tumour appeared as a solid, yellowish mass comparable with a schwannoma. Complete tumour resection was achieved via meticulous microsurgical technique and ultrasonic aspiration. Intraoperative monitoring (somatosensory-evoked potentials) remained stable during the entire surgical procedure.

Microscopic examination of tissue samples obtained during surgery showed spindle-shaped cells, arranged in a typical fascicular pattern. Small areas consisted of a hypocellular myxoid structure. Old haemorrhages were frequently seen. Immunohistochemistry revealed a strong homogenous reaction for S-100 protein but was negative for epithelial membrane antigen. The proliferation rate (Ki-67 staining) was low (Fig. 2). Altogether, these findings were consistent with a histopathological diagnosis of a schwannoma.

Postoperative recovery

Immediately after the surgery, the sensory and motor functions of the patient were intact. During the inpatient stay, the patient had a veritable postoperative course; the sensory impairments remained unchanged. Postoperative MRI of the cervical spine confirmed complete removal of the intramedullary lesion. Interestingly, the massive spinal cord edema decreased almost completely within 10 days after surgery (Fig. 1). The patient was discharged to medical rehabilitation. Follow-up examination 4 months after surgery revealed favourable, unchanged neurological condition (modified McCormick scale: grade I).

Material and methods

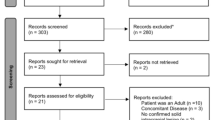

For this study, no experiments on human subjects or animals have been carried out. We performed a systematic review of the literature in PubMed, EMBASE and CENTRAL up to January 1, 2020, to retrieve all relevant studies and case reports on IMS. We used the keywords “intramedullary” simultaneous with “schwannoma OR neurinoma”. Selection criteria were the following: (1) at least one histological proven IMS reported, (2) available clinical information of the patient and (3) peer reviewed publication in a journal or book chapter. Studies published in other languages than English were included in order to receive a complete review of all reported cases. Melanotic IMS were excluded because of their reclassification as a distinct entity in 2016 [12]. In a second step, for complete identification, all reported studies on IMS have been analysed regarding additional cases of IMS. Each case which was mentioned in these articles was analysed with respect to our inclusion criteria. If not already found via keyword search, the case was added to our systematic review (Fig. 3).

Results

One hundred nineteen studies including 165 reported cases met our inclusion criteria. In only five cases, the patients harboured more than one IMS. Gender ratio was nearly 3:2 (male: female; 55.4% male; 39.2% female); mean age of disease presentation was 40.2 years (range 1 day–78 years); eleven patients suffered from NF (6.6%). A closer analysis of patients suffering from NF revealed that one patient had NF type 1, eight patients had NF type 2 and in two cases no information on the NF type was available. Most IMS were located in the cervical (45.8%) and thoracic (37.3%) spine; a smaller number was located in the cervicothoracic (6.2%), thoracolumbar (5.6%) and lumbar (2.3%) spine (Table 1).

We reviewed the included cases with respect to preoperative neurological status, the postoperative outcome and the follow-up, including tumour recurrence. In addition, we calculated the modified McCormick scale to determine the neurological status preoperatively and postoperatively. The analysis of preoperative neurological symptoms showed that sensory disturbance appeared in 67%, motor deficits in 68% and dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system, such as sphincter dysfunction, in 26% of the cases. The main duration of symptoms was 29 months. The preoperative neurological status according to the modified McCormick scale showed the following distribution: grade I (6%), grade II (27%), grade III (21%), grade IV (12%) and grade V (4%); in 30% of the cases, the preoperative modified McCormick scale was not determinable (Table 1).

Our review showed that 161 of 165 patients underwent surgery; in four cases, the diagnosis of IMS was made postmortem by autopsy. The analysis of the postoperative recovery revealed that complete recovery was achieved in 23%, symptom improvement in 51% and stable neurological condition in 4% of the cases. The neurological symptoms worsened in only 4% of cases and in another 4% the patient died after surgery. Information on the postoperative recovery was missing in 14% of the cases. The postoperative neurological status according to the modified McCormick scale showed the following distribution: grade I (16%), grade II (16%), grade III (19%), grade IV (10%) and grade V (3%); in 36% of the cases, the postoperative modified McCormick scale was not determinable (Table 1).

Additionally, we examined the postoperative outcome depending on the duration of symptoms. We defined “long duration of symptoms” as a duration of symptoms for more than 10 years. Patients with IMS and a duration of symptoms of < 10 years recovered completely in 23%, improved in 52% and were in stable neurological condition in 3% of cases; 5% these patients had worsening of symptoms and 4% died after operation. Patients with IMS and a duration of symptoms of ≥ 10 years recovered completely in only 17%, improved in 17% and were in stable neurological condition in 50%; none of these patients had worsening of symptoms or died after operation. Information on the postoperative outcome depending on the duration of symptoms was not determinable in 13% of the patients with a symptom duration < 10 years and in 16% of the patients with a symptom duration of ≥ 10 years.

The average duration of follow-up on a patient with IMS was 34 months. Tumour recurrence was only observed in 4% of the cases (Table 1).

Information on MRI images were available in only half of the cases. In the available T1-weighted images, most cases showed an isointense (18.1%) or hypointense (16.9%) imaging pattern; mixed (6.8%) and hyperintense (6.2%) patterns were observed less frequently. T2-weighted images showed in 23.2% a hyperintense, in 11.9% an isointense, in 8.5% a mixed and in 7.9% a hypointense pattern. All cases showed a gadolinium enhancement, which was homogenous in 32.8%, heterogenous in 18.6%, some cases showed only a circular (5.6%) and 2 cases were reported to only show minimal gadolinium enhancement (1.1%). 17.5% of the IMS showed a cystic component. Perifocal edema was observed in 22% of the cases; 20.9% of cases were associated with syringomyelia (Table 2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, no complete review of all reported cases has been performed thus far. Here, we attempted to gather all reported cases since 1932. Interestingly, we found more cases than previously described in other series [62, 80, 98]. Due to the language barrier, reports in Japanese, Chinese, French, Portuguese, German and Spanish were not included in previous reports. Additionally, keyword research in the known databases did not show all cases; further analysis of reported case series revealed cases, which were missed by keyword research of the databases. This series of 166 cases including our own study is the largest review of cases on IMS. An uncomplete review of this very rare pathology might constitute a limitation, which impacts the estimated epidemiology.

IMS represent 0.3–1.5% of all spinal schwannomas [2,3,4]. Several studies described a gender distribution of 3:1 (male:female) [93, 107, 113]. Our results showed a higher rate of female patients and thus a gender distribution of 3:2 (male:female). Previous studies found the mean age of disease presentation to be in the fourth decade of life [92, 113, 117]. The mean age of disease presentation in our series was 40.2 years (range: 1 day–78 years old). Thus, the analysis of our series confirmed the previously reported results. The cervical spine followed by the thoracic spine was reported as the most common localization of IMS [3, 85, 88, 89]. These findings are also consistent with our analysis.

Previous studies addressing the clinical features and surgical outcome of patients with IMS revealed sensory disturbance as the most common initial symptom [107]. Our results show that patients with IMS suffer from sensory deficits as often as from motor deficits, but we agree with Yang et al. on the value of sphincter dysfunction as a late symptom [107]. Overall, patients with IMS seem to benefit from operation, which is clearly shown by an improved postoperative neurological status in 86% of the patients. Previous studies on IMS observed that patients with a longer symptom duration benefit less from surgery due to chronical compression of the neuronal tissue by the tumour [107]. In our review, we were not able to confirm this hypothesis, since the analysis of the postoperative outcome as a function of the duration of symptoms revealed no significantly worse outcome for patients with a symptom duration ≥ 10 years. In most of the cases, gross total resection can be achieved easily [107]. In cases in which the tumour is strongly adherent to the surrounding neuronal tissue, subtotal resection should be considered in order to avoid deterioration of the neurological status. In particularly complicated cases, two-stage surgery provides a possible approach towards better therapeutical results [91].

Conti et al. stated that IMS associates with NF; however, several studies showed a prevalence of 0–2% in spinal tumours [7, 70, 80, 103, 125]. Our review found NF in 11 of 166 cases (6.6%). These results reveal slightly higher rates of NF in patients with IMS than previously described; however, no firm association between NF and IMS was found.

IMS are frequently misdiagnosed as another tumour entity because of the tumour location and its heterogenous appearance in MRI diagnostics [113, 122]. Several series described the MRI appearance of schwannomas as being iso/hypointense in the T1- and hyperintense in the T2-weighted images [1]. However, the T1- and T2-weighted appearance of IMS varies among studies [107, 113]. The summary of these studies in our review reveals that in most cases, IMS show a similar MRI appearance as schwannomas. Specifically, in T1-weighted images, 35% of all cases appeared iso- or hypointense and in T2-weighted images, 23.2% were hyperintense. Interestingly, 1/5 of all cases associated with syringomyelia and in 20%, a perilesional edema was observed. The treated patient in our institution suffered from a perilesional edema, which showed a complete remission in the follow-up MRI after 4 months.

The pathogenesis of IMS is controversially debated among experts because of the absence of Schwann cells within the central nervous system (CNS) in healthy individuals [69]. Currently, there are six hypotheses regarding the origin of IMS: (a) conversion of pial mesodermal cells into neuroectodermal Schwann cells [126]; (b) migration and late neoplastic growth of ectopic Schwann cells during embryonal development [18, 30]; (c) origin from Schwann cells from the perivascular nerve plexus surrounding the blood vessels within the CNS [17, 27, 36, 127, 128]; (d) schwannosis in proximity to the anterior spinal artery [129]; (e) centripetal growth from a dorsal nerve root entry zone into the spinal cord [20, 21, 26, 128] and (f) result from imperfect regeneration of the spinal cord after mechanical trauma or chronic disease [130].

Although some association of proliferating vessels around the tumour [4, 32, 35, 68, 102], tumour connection to a nerve root [4, 27, 34, 43, 46, 52, 58, 68, 71, 76, 77, 84, 89, 99, 104, 107, 109, 115, 123] or chronic disease of the spinal cord could be observed in reported cases [39, 100, 107], it is still not possible to make a general statement regarding the pathogenesis of IMS. In our case, a tumour connection to the nerve root could be observed in the MRI of the cervical spine. This is why we rather support the hypothesis of centripetal growth from a nerve root entry zone into the spinal cord as a possible pathomechanism for development of IMS. However, this mechanism is not able to explain the formation of multiple IMS. The special subgroup of multiple IMS might have implications for the pathomechanism of IMS, but the available information do not allow a conclusions about differences in the pathogenesis of singular and multiple IMS.

As part of the preoperative examination and consultation of patients with intramedullary tumours, it is important to make a correct tentative diagnosis to ensure the best possible treatment. Since IMS are benign tumours of the spinal cord, their treatment might differ from other tumours, like spinal astrocytoma or ependymoma. Patients with IMS show a low rate of tumour recurrence. Even in cases with subtotal tumour resection, tumour recurrence is not necessarily observed [107]. In contrast, for patients with spinal ependymoma, the gross total resection is the gold standard to achieve the longest possible progression-free survival [131,132,133,134]. Therefore, complete removal of the tumour should be the goal of the surgery. Furthermore, it is unclear if patients with spinal astrocytoma benefit from gross total resection as patients with spinal ependymoma do [135,136,137,138]. Additionally, gross total resection is difficult to achieve in patients with spinal astrocytoma without causing a worse neurological outcome, which is why the primary goal of surgery is to spare the surrounding nervous tissue [139, 140]. Unfortunately, spinal astrocytoma and ependymoma are difficult to distinguish from IMS by use of MRI [107, 113, 141]. Therefore, it seems to be important to differentiate intramedullary tumours during surgery with the aid of intraoperative frozen sections in order to provide the patient with the best possible therapy [95, 104].

Conclusion

IMS are rare tumours of the spinal cord. One hundred sixty-six cases have been reported so far, including the here reported case. IMS are more frequently found in male patients; the mean age of disease presentation is the fourth decade of life. The most common localization of IMS is the cervical spine, followed by the thoracic spine. Although several explanations regarding the pathogenesis of IMS have been proposed, it is still not possible to make a general statement regarding the pathogenesis of these tumours, especially for the subgroup of patients with multiple IMS. In our study, no firm association between NF and IMS was found.

Patients suffering from IMS present in most of the cases with sensory and motor deficits; sphincter dysfunction seems to be a late symptom. Due to heterogenous imaging patterns in MRI, it is difficult to preoperatively differentiate an IMS from other intramedullary tumours. Therefore, intraoperative frozen section might be useful to determine the tumour entity and the best suited surgical strategy. Overall, patients with IMS seem to benefit from operation; in most of the cases, gross total resection can be achieved easily. Nevertheless, further multicentre studies are necessary to elucidate the pathomechanism leading to IMS formation and to determine strategies for the best clinical care for these patients.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Ottenhausen M, Ntoulias G, Bodhinayake I, Ruppert F-H, Schreiber S, Förschler A, Boockvar JA, Jödicke A (2019) Intradural spinal tumors in adults-update on management and outcome. Neurosurg Rev 42:371–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-018-0957-x

Lee DY, Chung CK, Kim HJ (1999) Thoracic intramedullary schwannoma. J Spinal Disord 12:174–176

Riffaud L, Morandi X, Massengo S, Carsin-Nicol B, Heresbach N, Guegan Y (2000) MRI of intramedullary spinal schwannomas: case report and review of the literature. Neuroradiology 42:275–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002340050885

Ross DA, Edwards MS, Wilson CB (1986) Intramedullary neurilemomas of the spinal cord: report of two cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 19:458–464. https://doi.org/10.1227/00006123-198609000-00023

Bernal-García LM, Cabezudo-Artero JM, Ortega-Martínez M, Porras-Estrada LF, Fernández-Portales I, Ugarriza-Echebarrieta LF, Molina-Orozco M, Pimentel-Leo JJ (2010) Intramedullary schwannomas. Report of two cases. Neurocir Astur Spain 21:232–238 discussion 238-239

Bhayani R, Goel A (1996) Multiple intramedullary schwannomas--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 36:466–468. https://doi.org/10.2176/nmc.36.466

Kushel’ YV, Belova YD, Tekoev AR (2017) Intramedullary spinal cord tumors and neurofibromatosis. Zh Vopr Neirokhir Im N N Burdenko 81:70–73. https://doi.org/10.17116/neiro201780770-73

Pardatscher K, Iraci G, Cappellotto P, Rigobello L, Pellone M, Fiore D (1979) Multiple intramedullary neurinomas of the spinal cord. Case report. J Neurosurg 50:817–822. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1979.50.6.0817

Sloof, J.L., Kernohan, J.W., McCarty, C.S., 1964. Primary intramedullary tumors of the spinal cord and filum terminale. Philadelphia: Saunders Company Ed.

McCormick PC, Torres R, Post KD, Stein BM (1990) Intramedullary ependymoma of the spinal cord. J Neurosurg 72:523–532. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1990.72.4.0523

Schneider C, Hidalgo ET, Schmitt-Mechelke T, Kothbauer KF (2014) Quality of life after surgical treatment of primary intramedullary spinal cord tumors in children. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 13:170–177. https://doi.org/10.3171/2013.11.PEDS13346

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW (2016) The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 131:803–820. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1

Penfield W (1932) Cytology and pathology of the central nervous system, 3rd edn. P.B. Hoeber, Incorporated

Rasmussen TB, Kernohan JW, Adson AW (1940) Pathologic classification, with surgical consideration, of intraspinal tumors. Ann Surg 111:513–530. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-194004000-00001

Roka L (1951) Clinical aspects and pathologic anatomy of tumors of the oblongata and cord in the region of the foramen magna. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkrankh Ver Mit Z Gesamte Neurol Psychiatr 186:413–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00716069

Rose K (1954) Neurohistopathologic study of Recklinghausen’s disease; a contribution to the formal genesis of juxta- and intramedullary neurinoma. Psychiatr Neurol Med Psychol (Leipz) 6:163–173

Riggs HE, Clary WU (1957) A case of intramedullary sheath cell tumor of the spinal cord; consideration of vascular nerves as a source of origin. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 16:332–336. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005072-195707000-00004

Ramamurthi B, Anguli VC, Iyer CG (1958) A case of intramedullary neurinoma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 21:92–94. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.21.2.92

Scott M, Bentz R (1962) Intramedullary neurilemmoma (neurinoma) of the thoracic cord. A case report. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 21:194–200. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005072-196204000-00003

Mccormick WF (1964) Intramedullary spinal cord schwannoma. A unique case. Arch Pathol 77:378–382

Mason TH, Keigher HA (1968) Intramedullary spinal neurilemmoma: case report. J Neurosurg 29:414–416. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1968.29.4.0414

Chigasaki H, Pennybacker JB (1968) A long follow-up study of 128 cases of intramedullary spinal cord tumours. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 10:25–66. https://doi.org/10.2176/nmc.10.25

van Duinen MT (1971) Intramedullary neurinoma. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 115:1070–1074

Fabres A, Conocente Y, Chiorino S (1985) Neurinoma intramedullar dorsal. Presentacion de un caso. Clin Neurochir 30:100–102

Cambier J, Masson M, Hurth M, Poirier J, Dehen H (1974) Unilateral posterior-column syndrome due to intramedullary neurinoma. Imitative homolateral synkinesias. Rev Neurol (Paris) 130:189–199

Wood WG, Rothman LM, Nussbaum BE (1975) Intramedullary neurilemoma of the cervical spinal cord. Case report. J Neurosurg 42:465–468. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1975.42.4.0465

Schmitt HP (1975) “Epi-” and intramedullary neurilemmoma of the spinal cord with denervation atrophy in the related skeletal muscles. J Neurol 209:271–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00314366

Isu T, Tashiro K, Mitsumori K, Sato M, Tsuru M (1976) A case of intramedullary spinal schwanoma (author’s transl). No Shinkei Geka 4:897–901

Kumar S, Gulati DR (1977) Intramedullary neurilemmoma. A case report. Neurol India 25:255–256

Vailati G, Occhiogrosso M, Troccoli V (1979) Intramedullary thoracic schwannoma. Surg Neurol 11:60–62

Gegalian L (1979) Use of hyaluronidase in the central nervous system. Surg Neurol 12:3–5

Shalit MN, Sandbank U (1981) Cervical intramedullary schwannoma. Surg Neurol 16:61–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-3019(81)80069-9

Guidetti B (1967) Intramedullary tumours of the spinal cord. Acta Neurochir 17:7–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01670413

Cantore G, Ciappetta P, Delfini R, Vagnozzi R, Nolletti A (1982) Intramedullary spinal neurinomas. J Neurosurg 57:143–147. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1982.57.1.0143

Lesoin F, Delandsheer E, Krivosic I, Clarisse J, Arnott G, Jomin M, Bouchez B (1983) Solitary intramedullary schwannomas. Surg Neurol 19:51–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-3019(83)90211-2

Rout D, Pillai SM, Radhakrishnan VV (1983) Cervical intramedullary schwannoma. Case report. J Neurosurg 58:962–964. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1983.58.6.0962

Kang JK, Song JU (1983) Intramedullary spinal schwannoma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 46:1154–1155. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.46.12.1154-a

Bouchez B, Delandsheer JM, Arnott G (1984) Solitary intramedullary neurinomas. Apropos of a case located in the cervical spine. LARC Med 4:26–28

Drapkin AJ, Rose WS, Pellmar MB (1985) Chiari type I malformation with an associated intramedullary schwannoma. Surg Neurol 24:511–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-3019(85)90266-6

Lesoin F, Rousseaux M, Pruvo JP, Villette L, Jomin M (1986) Solitary intraspinal dorsal neurinoma. A case report. Rev Med Interne 7:387–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0248-8663(86)80128-x

Maruki C, Ito M, Sumie H, Sato K, Ishii S (1986) Intramedullary schwannoma with extradural extension: case report. No Shinkei Geka 14:579–584

Char G, Cross JN (1987) Intramedullary schwannoma of the spinal cord. West Indian Med J 36:35–38

Garen PD, Collett MG, Harper CG (1988) Solitary cervical intra- and extramedullary schwannoma. Pathology (Phila) 20:296–298. https://doi.org/10.3109/00313028809059511

Hida K, Akino M, Isu T, Saitoh H, Iwasaki Y, Abe H (1988) Multiple neurinoma of the spinal cord: case report. No Shinkei Geka 16:1489–1493

Okuda Y, Tamaki N, Nameta A, Izawa I, Tomita Y, Kokunai T, Ehara K, Matsumoto S (1988) Intramedullary invasion by a cervical cystic neurinoma--a case report. No Shinkei Geka 16:173–178

Gorman PH, Rigamonti D, Joslyn JN (1989) Intramedullary and extramedullary schwannoma of the cervical spinal cord--case report. Surg Neurol 32:459–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-3019(89)90012-8

Sharma SC, Ray RC, Banerjee AK (1989) Intramedullary spinal schwannoma. Indian Pediatr 26:290–292

Meisel HJ, Patt S, Brock M (1990) Intramedullary neurinoma. Case report. Zentralbl Neurochir 51:171–173

Li MH, Holtås S (1991) MR imaging of spinal intramedullary tumors. Acta Radiol Stockh Swed 1987(32):505–513

Herregodts P, Vloeberghs M, Schmedding E, Goossens A, Stadnik T, D’Haens J (1991) Solitary dorsal intramedullary schwannoma. Case report. J Neurosurg 74:816–820. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1991.74.5.0816

Jacquet G, Czorny A, Godard J, Steimle R, Wendling D (1992) Intramedullary neurinoma. Apropos of a case. Review of the literature. Neurochirurgie. 38:315–321

Morimoto T, Sasaki T, Mochizuki T, Takakura K, Sato A (1992) Thoracic intramedullary neurinoma with multiple intracranial meningiomas; case report. No Shinkei Geka 20:423–427

Benini A, Binggeli RS, Ebeling U, Fretz C, Diener PA, Molteni F (1993) Solitary intramedullary neurinoma: report of two cases and review of the literature. Neuro-Orthopedics 15:39–50

Sekerci Z, Iyigün Ö, Kandemir B, Celik F (1993) Intramedullary schwannoma of the thoracic spinal cord-case report. Turk Neurosurg 3:28–30

Radhakrishnan VV, Saraswathy A, Radhakrishnan NS, Rout D (1993) Diagnostic utility of immunohistochemical techniques in intramedullary Schwann-cell tumours. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 36:87–91

Nicoletti GF, Passanisi M, Castana L, Albanese V (1994) Intramedullary spinal neurinoma: case report and review of 46 cases. J Neurosurg Sci 38:187–191

Duong H, Tampieri D, Melançon D, Salazar A, Robert F, Alwatban J (1995) Intramedullary schwannoma. Can Assoc Radiol J J Assoc Can Radiol 46:179–182

Melancia JL, Pimentel JC, Conceicao I, Antunes JL (1996) Intramedullary neuroma of the cervical spinal cord: case report. Neurosurgery 39:594–598

Botelho CH, Kalil RK, Masini M (1996) Spinal cord schwannoma: case report. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 54:498–504. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0004-282x1996000300023

Innocenzi G, Cervoni L, Caruso R (1997) Intramedullary cervical neurinoma. A case report and review of the literature. Minerva Chir 52:679–682

Bekar A, Dogan S, Cordan T, Tolunay S (1997) Cervical intramedullary and extramedullary schwannoma. Turkish Neurosurg 7:28–32

Beşkonakli E, Cayli S, Turgut M, Bostanci U, Seçkin S, Yalçinlar Y (1997) Intraparenchymal schwannomas of the central nervous system: an additional case report and review. Neurosurg Rev 20:139–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01138200

Chitoku S, Kawai S, Watabe Y, Nishitani M, Iwahashi H, Aketa S (1998) A case report of neurofibromatosis type 2 associated with multiple intracranial and spinal tumors: management of intramedullary spinal tumors in neurofibromatosis type 2. Jpn J Neurosurg 7:707–710. https://doi.org/10.7887/jcns.7.707

Kotil K, Gözüm T, Yilmaz C (1998) A case of neurofibromatosis-2 associated with multiple spinal tumors. Turkish Neurosurg 8:53–56

Hejazi N, Hassler W (1998) Microsurgical treatment of intramedullary spinal cord tumors. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 38:266–271; discussion 271-273. https://doi.org/10.2176/nmc.38.266

Binatli O, Erşahin Y, Korkmaz O, Bayol U (1999) Intramedullary schwannoma of the spinal cord. A case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Sci 43:163–167 discussion 167-168

Arellanes-Chávez CA, Alvarez-Betancourt L (2000) Schwannoma intramedular cervical. Arch Neurocien (Mex) 5:29–31

Ogungbo BI, Strachan RD, Bradey N (2000) Cervical intramedullary schwannoma: complete excision using the KTP laser. Br J Neurosurg 14:345–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/026886900417351

Kodama Y, Terae S, Hida K, Chu BC, Kaneko K, Miyasaka K (2001) Intramedullary schwannoma of the spinal cord: report of two cases. Neuroradiology 43:567–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002340100540

Patronas NJ, Courcoutsakis N, Bromley CM, Katzman GL, MacCollin M, Parry DM (2001) Intramedullary and spinal canal tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis 2: MR imaging findings and correlation with genotype. Radiology 218:434–442. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.218.2.r01fe40434

Kono K, Inoue Y, Nakamura H, Shakudo M, Nakayama K (2001) MR imaging of a case of a dumbbell-shaped spinal schwannoma with intramedullary and intradural-extramedullary components. Neuroradiology 43:864–867. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002340100599

Maira G, Amante P, Denaro L, Mangiola A, Colosimo C (2001) Surgical treatment of cervical intramedullary spinal cord tumors. Neurol Res 23:835–842. https://doi.org/10.1179/016164101101199432

Sasaki M, Yamamoto H, Nagashima M, Yamamoto K, Kawano K, Yoshida K, Miyauchi A (2002) A case of cervical intramedullary schwannoma with intratumoral hemorrhage. Jpn J Neurosurg 11:750–753

Darwish BS, Balakrishnan V, Maitra R (2002) Intramedullary ancient schwannoma of the cervical spinal cord: case report and review of literature. J Clin Neurosci 9:321–323. https://doi.org/10.1054/jocn.2001.0952

Brown KM, Dean A, Sharr MM (2002) Thoracic intramedullary schwannoma. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 28:421–424. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2990.2002.00415.x

O’Brien DF, Farrell M, Fraher JP, Bolger C (2003) Schwann cell invasion of the conus medullaris: case report. Eur Spine J 12:328–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-002-0484-9

Colosimo C, Cerase A, Denaro L, Maira G, Greco R (2003) Magnetic resonance imaging of intramedullary spinal cord schwannomas. Report of two cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg 99:114–117. https://doi.org/10.3171/spi.2003.99.1.0114

Panagiotopoulos K, Tortora F, Elefante A, Bruno MC, Santangelo M, Cirillo S, Briganti F, Cerillo A (2004) Solitary thoracic intramedullary schwannoma report of two cases. Riv Neuroradiol 17:99–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/197140090401700113

Siddiqui AA, Shah AA (2004) Complete surgical excision of intramedullary schwannoma at the craniovertebral junction in neurofibromatosis type-2. Br J Neurosurg 18:193–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/02688690410001681109

Conti P, Pansini G, Mouchaty H, Capuano C, Conti R (2004) Spinal neurinomas: retrospective analysis and long-term outcome of 179 consecutively operated cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol 61:34–43; discussion 44. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-3019(03)00537-8

Chávez López JA, Rodríguez Díaz D, Cisneros Medina Y, Sánchez Jerónimo H, Zarate Méndez A, González Vázquez A, Hernández Salazar M (2004) Schwannoma intramedular cervical. Arch Neurocien (Mex) 9:55–58

El Malki M, Bertal A, Sami A, Ibahoin K, Lakhdar A, Naja A, Achouri M, Ouboukhlik A, El Kamar A, El Azhari A (2005) Intramedullary schwannoma. A case report. Neurochirurgie. 51:19–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0028-3770(05)83416-2

Amato VG, Assietti R, Morosi M, Arienta C (2005) Acute brainstem dissection of syringomyelia associated with cervical intramedullary neurinoma. Neurosurg Rev 28:163–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-004-0362-5

Matsuyama Y, Sakai Y, Katayama Y, Imagama S, Ito Z, Wakao N, Sato K, Kamiya M, Yukawa Y, Kanemura T, Yanase M, Ishiguro N (2009) Surgical results of intramedullary spinal cord tumor with spinal cord monitoring to guide extent of resection. J Neurosurg Spine 10:404–413. https://doi.org/10.3171/2009.2.SPINE08698

Kim S-D, Nakagawa H, Mizuno J, Inoue T (2005) Thoracic subpial intramedullary schwannoma involving a ventral nerve root: a case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol 63:389–393; discussion 393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surneu.2004.03.023

Kyoshima K, Horiuchi T, Zenisaka H, Nakazato F (2005) Thoracic dumbbell intra- and extramedullary schwannoma. J Clin Neurosci 12:481–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2004.06.015

Shenoy SN, Raja A (2005) Cystic cervical intramedullary schwannoma with syringomyelia. Neurol India 53:224–225. https://doi.org/10.4103/0028-3886.16419

Kahilogulları G, Aydın Z, Ayten M, Attar A, Erdem A (2005) Schwannoma of the conus medullaris. J Clin Neurosci 12:80–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2004.02.016

Ho T, Tai KS, Fan YW, Leong LLY (2006) Intramedullary spinal schwannoma: case report and review of preoperative magnetic resonance imaging features. Asian J Surg 29:306–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60108-1

Mukerji G, Sherekar S, Yadav YR, Chandrakar SK, Raina VK (2007) Pediatric intramedullary schwannoma without neurofibromatosis. Neurol India 55:54–56. https://doi.org/10.4103/0028-3886.30428

Hida K, Yano S, Iwasaki Y (2008) Staged operation for huge cervical intramedullary schwannoma: report of two cases. Neurosurgery 62:ONS456-460; discussion ONS460. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.neu.0000326035.54714.cc

Kim NR, Suh Y-L, Shin H-J (2009) Thoracic pediatric intramedullary schwannoma: report of a case. Pediatr Neurosurg 45:396–401. https://doi.org/10.1159/000260911

Nicácio JM, Rodrigues JC, Galles MHL, Faquini IV, de Brito Pereira CA, Ganau M (2009) Cervical intramedullary schwannoma: a case report and review of the literature. Rare Tumors 1:e44. https://doi.org/10.4081/rt.2009.e44

Hayashi F, Sakai T, Sairyo K, Hirohashi N, Higashino K, Katoh S, Yasui N (2009) Intramedullary schwannoma with calcification of the epiconus. Spine J 9:e19–e23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2008.11.006

Ohtonari T, Nishihara N, Ota T, Ota S, Koyama T (2009) Intramedullary schwannoma of the conus medullaris complicated by dense adhesion to neural tissue. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 49:536–538. https://doi.org/10.2176/nmc.49.536

Adam Y, Benezech J, Blanquet A, Fuentes J-M, Bousigue J-Y, Debono B, Duplessis É, Espagno C, Plas J-Y, Lescure J-P, Destandau J, Hladky J-P, Grunewald P, Mahla K, Remond J, Louis É (2010) Les tumeurs intramédullaires. Résultat d’une enquête nationale en neurochirurgie libérale. Neurochirurgie 56:344–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuchi.2009.11.003

Lyle CA, Malicki D, Senac MO, Levy ML, Crawford JR (2010) Congenital giant intramedullary spinal cord schwannoma. Neurology 75:1752. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fc29f2

Teo L-C, Shen C-Y, Tsai C-H, Liu J-T (2012) Intramedullary schwannoma of the cervical spinal cord. Formos J Surg 45:146–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fjs.2012.06.002

Ryu K-S, Lee K-Y, Lee H-J, Park C-K (2011) Thoracic intramedullary schwannoma accompanying by extramedullary beads-like daughter schwanommas. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 49:302–304. https://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2011.49.5.302

Vij M, Jaiswal S, Jaiswal AK, Behari S (2011) Coexisting intramedullary schwannoma with intramedullary cysticercus: report of an unusual collision. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 54:866–867. https://doi.org/10.4103/0377-4929.91541

Das KK, Jaiswal AK, Behari S (2012) Synchronous tricompartmental benign CNS tumors with tonsillar herniation, cervicodorsal syringomyelia and hydrocephalus. Indian J Surg 74:420–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-012-0463-2

Li J, Ke Y, Huang M, Li Z, Wu Y (2013) Microexcision of intramedullary schwannoma at the thoracic vertebra. Exp Ther Med 5:845–847. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2013.890

Lee M, Rezai AR, Freed D, Epstein FJ (1996) Intramedullary spinal cord tumors in neurofibromatosis. Neurosurgery 38:32–37. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006123-199601000-00009

Lee SE, Chung CK, Kim H-J (2013) Intramedullary schwannomas: long-term outcomes of ten operated cases. J Neuro-Oncol 113:75–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-013-1091-9

Eljebbouri B, Gazzaz M, Akhaddar A, Elmostarchid B, Boucetta M (2013) Pediatric intramedullary schwannoma without neurofibromatosis: case report. Acta Med Iran 51:727–729

Wu L, Yao N, Chen D, Deng X, Xu Y (2011) Preoperative diagnosis of intramedullary spinal schwannomas. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 51:630–634. https://doi.org/10.2176/nmc.51.630

Yang T, Wu L, Deng X, Yang C, Xu Y (2014) Clinical features and surgical outcomes of intramedullary schwannomas. Acta Neurochir 156:1789–1797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-014-2168-8

Yang T, Wu L, Yang C, Deng X, Xu Y (2015) Coexisting intramedullary schwannoma with an ependymal cyst of the conus medullaris: a case report. Oncol Lett 9:903–906. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2014.2786

Gupta A, Nair BR, Chacko G, Mani S, Joseph V (2015) Cervical intramedullary schwannoma mimicking a glioma. Asian J Neurosurg 10:42–44. https://doi.org/10.4103/1793-5482.151509

Jagannatha AT, Joshi KC, Rao S, Srikantha U, Varma RG, Mahadevan A (2016) Paediatric calcified intramedullary schwannoma at conus: a common tumor in a vicarious location. J Pediatr Neurosci 11:319–321. https://doi.org/10.4103/1817-1745.199474

Sun J, Teo M, Wang Z, Li Z, Wu H, Zheng M, Chang Q, Han Y, Cui Z, Chen M, Wang T, Chen X (2017) Characteristic and surgical results of multisegment intramedullary cervical spinal cord tumors. Interdiscip Neurosurg 7:29–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inat.2016.11.004

Nayak R, Chaudhuri A, Chattopadhyay A, Ghosh SN (2015) Thoracic intramedullary schwannoma: a case report and review of literature. Asian J Neurosurg. 10:126–128. https://doi.org/10.4103/1793-5482.145155

Gao L, Sun B, Han F, Jin Y, Zhang J (2017) Magnetic resonance imaging features of intramedullary schwannomas. J Comput Assist Tomogr 41:137–140. https://doi.org/10.1097/RCT.0000000000000493

Karatay M, Koktekir E, Erdem Y, Celik H, Sertbas I, Bayar MA (2017) Intramedullary schwannoma of conus medullaris with syringomyelia. Asian J Surg 40:240–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asjsur.2014.04.004

Li X, Xu G, Su R, Lv J, Lai X, Yu X (2017) Intramedullary schwannoma of the upper cervical spinal cord: a case study of identification in pathologic autopsy. Forensic Sci Res 2:46–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/20961790.2016.1265236

Navarro Fernández JO, Monroy Sosa A, Cacho Díaz B, Arrieta VA, Ortíz Leyva RU, Cano Valdez AM, Reyes Soto G (2018) Cervical intramedullary schwannoma: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Neurol 10:18–24. https://doi.org/10.1159/000467389

Landi A, Grasso G, Gregori F, Iacopino G, Ruggeri A, Delfini R (2018) Isolated pediatric intramedullary schwannoma: case report and review of literature. World Neurosurg 115:417–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.04.220

Singh R, Chaturvedi S, Pant I, Singh G, Kumari R (2018) Intramedullary schwannoma of conus medullaris: rare site for a common tumor with review of literature. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 4:99. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-018-0134-z

Wang K, Zhao J, Zhang Y, Su Y (2018) Pediatric intramedullary schwannoma with syringomyelia: a case report and literature review. BMC Pediatr 18:374. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1341-2

Shi W, Wang S, Zhang H, Wang G, Guo Y, Sun Z, Wu Y, Zhang P, Jing L, Zhao B, Xing J, Wang J, Wang G (2019) Risk factor analysis of progressive spinal deformity after resection of intramedullary spinal cord tumors in patients who underwent laminoplasty: a report of 105 consecutive cases. J. Neurosurg. Spine 30:655–663. https://doi.org/10.3171/2018.10.SPINE18110

Dhake RP, Chatterjee S (2019) Recurrent thoracic intramedullary schwannoma: report of two cases with long term follow up. Br J Neurosurg 1–4:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/02688697.2019.1566516

Dai LM, Qiu Y, Cen B, Lv J (2019) Intramedullary schwannoma of cervical spinal cord presenting inconspicuous enhancement with gadolinium. World Neurosurg. 127:418–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.04.118

Sekar S, Vinayagamani S, Thomas B, Poyuran R, Kesavadas C (2019) Haemosiderin cap sign in cervical intramedullary schwannoma mimicking ependymoma: how to differentiate? Neuroradiology 61:945–948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-019-02229-6

Kelly A, Lekgwara P, Younus A (2020) Extensive intramedullary schwannoma of the sub-axial cervical spine–a case report. Interdiscip. Neurosurg. 19:100621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inat.2019.100621

Mautner VF, Tatagiba M, Lindenau M, Fünsterer C, Pulst SM, Baser ME, Kluwe L, Zanella FE (1995) Spinal tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2: MR imaging study of frequency, multiplicity, and variety. AJR Am J Roentgenol 165:951–955. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.165.4.7676998

Russell, D., Rubinstein, L., 1963. Pathology of tumors of the nervous system. E. Arnold, p. pp 23. 34. 243. 244

Kernohan W (1941) Tumors of the spinal cord. Arch Pathol:843–883

Lu A, Kypridakis G, Abbott K, Vogel P (1963) Intramedullary neurofibromas of the cervical cord. Report of two cases. Bull Los Angeles Neurol Soc:31–36

Adelman LS, Aronson SM (1972) Intramedullary nerve fiber and Schwann cell proliferation within the spinal cord (schwannosis). Neurology 22:726–731. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.22.7.726

Wolman L (1967) Post-traumatic regeneration of nerve fibres in the human spinal cord and its relation to intramedullary neuroma. J Pathol Bacteriol 94:123–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1700940116

Boström A, Kanther N-C, Grote A, Boström J (2014) Management and outcome in adult intramedullary spinal cord tumours: a 20-year single institution experience. BMC Res Notes 7:908. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-908

Feldman WB, Clark AJ, Safaee M, Ames CP, Parsa AT (2013) Tumor control after surgery for spinal myxopapillary ependymomas: distinct outcomes in adults versus children. J. Neurosurg. Spine 19:471–476. https://doi.org/10.3171/2013.6.SPINE12927

Harrop JS, Ganju A, Groff M, Bilsky M (2009) Primary intramedullary tumors of the spinal cord. Spine 34:S69–S77. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b95c6f

Wostrack M, Ringel F, Eicker SO, Jägersberg M, Schaller K, Kerschbaumer J, Thomé C, Shiban E, Stoffel M, Friedrich B, Kehl V, Vajkoczy P, Meyer B, Onken J (2018) Spinal ependymoma in adults: a multicenter investigation of surgical outcome and progression-free survival. J Neurosurg Spine 28:654–662. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.9.SPINE17494

Ahmed R, Menezes AH, Awe OO, Torner JC (2014) Long-term disease and neurological outcomes in patients with pediatric intramedullary spinal cord tumors. J Neurosurg Pediatr 13:600–612. https://doi.org/10.3171/2014.1.PEDS13316

Bansal S, Ailawadhi P, Suri A, Kale SS, Sarat Chandra P, Singh M, Kumar R, Sharma BS, Mahapatra AK, Sharma MC, Sarkar C, Bithal P, Dash HH, Gaikwad S, Mishra NK (2013) Ten years’ experience in the management of spinal intramedullary tumors in a single institution. J Clin Neurosci 20:292–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2012.01.056

Garcés-Ambrossi GL, McGirt MJ, Mehta VA, Sciubba DM, Witham TF, Bydon A, Wolinksy J-P, Jallo GI, Gokaslan ZL (2009) Factors associated with progression-free survival and long-term neurological outcome after resection of intramedullary spinal cord tumors: analysis of 101 consecutive cases. J Neurosurg Spine 11:591–599. https://doi.org/10.3171/2009.4.SPINE08159

Khalid S, Kelly R, Carlton A, Wu R, Peta A, Melville P, Maasarani S, Meyer H, Adogwa O (2019) Adult intradural intramedullary astrocytomas: a multicenter analysis. J Spine Surg 5:19–30. https://doi.org/10.21037/jss.2018.12.06

Hamilton KR, Lee SS, Urquhart JC, Jonker BP (2019) A systematic review of outcome in intramedullary ependymoma and astrocytoma. J Clin Neurosci 63:168–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2019.02.001

Minehan KJ, Brown PD, Scheithauer BW, Krauss WE, Wright MP (2009) Prognosis and treatment of spinal cord astrocytoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 73:727–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.060

Hussain I, Parker WE, Barzilai O, Bilsky MH (2020) Surgical management of intramedullary spinal cord tumors. Neurosurg Clin N Am 31:237–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nec.2019.12.004

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Milad Neyazi for the translation of Japanese publications.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All mentioned authors contributed to the study conception and design. Literature search and data collection were performed by VMS. Data analysis and writing of the first manuscript draft were performed by VMS and BN. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Consent to participate

Patient consent was obtained.

Consent for publication

Patient consent was obtained.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Swiatek, V.M., Stein, KP., Cukaz, H.B. et al. Spinal intramedullary schwannomas—report of a case and extensive review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev 44, 1833–1852 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-020-01357-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-020-01357-5