Abstract

Teleost sex differentiation largely depends on the number of undifferentiated germ cells. Here, we describe the generation and characterization of a novel transgenic zebrafish line, Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg, which specifically labels the whole lifetime of germ cells, i.e., from primordial germ cells (PGCs) at shield stage to the oogonia and early stage of oocytes in the ovary and to the early stage of spermatogonia, spermatocyte, and spermatid in the testis. By using this transgenic line, we carefully observed the numbers of PGCs from early embryonic stage to juvenile stage and the differentiation process of ovary and testis. The numbers of PGCs became variable at as early as 1 day post-fertilization (dpf). Interestingly, the embryos with a high amount of PGCs mainly developed into females and the ones with a low amount of PGCs mainly developed into males. By using transient overexpression and transgenic induction of PGC-specific bucky ball (buc), we further proved that induction of abundant PGCs at embryonic stage promoted later ovary differentiation and female development. Taken together, we generate an ideal transgenic line Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg which can visualize zebrafish germline for a lifetime, and we have utilized this line to study germ cell development and gonad differentiation of teleost and to demonstrate that the increase of PGC number at embryonic stage promotes female differentiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In a large amount of teleosts, the number of undifferentiated germ cells strongly contribute to sex differentiation and sexual dimorphism. For instance, in zebrafish (Danio rerio), medaka (Oryzias latipes), Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus), and even the gynogenetic all-female fish, Carassius gibelio, depletion of primordial germ cells usually leads to all-male development (Houwing et al. 2007; Lewis et al. 2008; Li et al. 2017; Saito et al. 2007; Siegfried and Nusslein-Volhard 2008). Previous studies have shown that zebrafish, although possesses a polygenetic sex determination system, shows different germ cell proliferations between definitive male and definitive female in larval stage at 14 days post-fertilization (dpf) (Liew et al. 2012; Tong et al. 2010; Tzung et al. 2015). A strong male-biased sex ratio was observed in primordial germ cell (PGC)-less population, indicating that a threshold number of PGCs is required for ovarian differentiation (Tzung et al. 2015). Transplantation of a single PGC into a germ cell-deficient embryos generates males exclusively in zebrafish (Saito et al. 2008). However, whether the initial PGC number at early embryonic stage contributes to zebrafish sex differentiation remains largely unknown.

The gonadal differentiation process of teleost has been thoroughly described using zebrafish as a model system. Zebrafish gonad in 17–21 dpf larva is generally considered to be undifferentiated (Rodriguez-Mari et al. 2005; Tzung et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2007). Primary testis and ovary are morphologically and molecularly distinguishable at around 30 dpf (Rodriguez-Mari et al. 2005). During testis differentiation, a “juvenile ovary-to-testis” transformation process usually occurs from 30 to 40 dpf (Maack and Segner 2003; Wang et al. 2007), which is accompanied by the Tp53-mediated apoptosis of oocytes (Rodriguez-Mari et al. 2010; Uchida et al. 2002). The cysts containing spermatogonia, spermatocytes, and spermatids can be observed in testes of males at 2 months post-fertilization (mpf) (Leu and Draper 2010; Maack and Segner 2003). The differentiation of ovary is considered to start earlier and to last for longer than that of the testis. The perinuclear oocytes (stage 1B) can be visible from 25 to 40 dpf (Lau et al. 2016; Siegfried and Nusslein-Volhard 2008), the cortical alveolar oocytes (stage II) are identical from 50 dpf (Krovel and Olsen 2004), and the matured oocytes form at 3 mpf (Yang et al. 2017). However, most of the previous results rely on chemical staining or immunostaining on gonad sections; the gonad development of zebrafish has never been investigated at the intact-gonad level with high resolution for a lifetime duration, which largely relies on a transgenic line labeling the whole lifetime of germ cells.

Several transgenic lines have been generated to visualize different types of germ cells at different stages of zebrafish. For undifferentiated germ cells, the askops (kop) promoter has been used to label the migrating PGCs until 3 dpf (Blaser et al. 2005), the Tg(ddx4:ddx4-EGFP)zf45Tg (previous name: Tg(vasa:EGFP)) can be used to label PGCs from 1 dpf (Krovel and Olsen 2002), the piwil1 promoter in Tg(piwil1:EGFP)uc1Tg (previous name: Tg(ziwi:EGFP)) can specifically drive EGFP expression in the undifferentiated germ cells after 7 dpf (Leu and Draper 2010), and by using a Gal4/UAS system and the kop promoter, our previous study has shown that the undifferentiated germ cells could be visible from the shield stage to 25 dpf (Xiong et al. 2013). For female germ cells, the Tg(-0.5zp3b:GFP) m1032Tg (previous name: Tg(zpc0.5:EGFP)) labels all stages of oocytes (Onichtchouk et al. 2003), the vasa promotor can be used to label the early stages of oocyte but not oogonia (pre-meiotic germ cells) (Krovel and Olsen 2004; Leu and Draper 2010; Wang et al. 2007), and Tg(piwil1:EGFP)uc1Tg could specifically label the oogonia and oocytes (Leu and Draper 2010), whereas the Tg(alk8:EGFP) only labels the early chromatin nucleolus-stage oocytes (stage IA oocytes) (Payne-Ferreira et al. 2004). For male germ cells, both Tg(ddx4:ddx4-EGFP)zf45Tg and Tg(piwil1:EGFP)uc1Tg label the spermatogonia and spermatocytes (Leu and Draper 2010). To the best of our knowledge, there is no report of transgenic fish labeling the whole lifetime of germ cells, from the early PGCs to the fully differentiated gametes.

In order to accomplish a lifetime visualization of zebrafish germ cells, early post-transcription regulation elements like nanos3 3′-UTR and later transcriptional regulation sequences such as piwil1 promoter might be coordinately combined. Piwil1 belongs to Argonaute protein family which interacts with Piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA) to mediate the post-transcriptional regulation of mRNA and transposon silencing in the animal germ line (Houwing et al. 2007), and a 4.7-kb promoter region could direct the expression of EGFP in germ cells from 7 dpf (Leu and Draper 2010). Nanos3 is one of the germ plasm components and is essential for maintaining oocyte production (Draper et al. 2007; Kosaka et al. 2007). During early embryogenesis, the specific region of 3′-UTR of nanos3 can be recognized by the miR430 which mediate maternal mRNA degradation (Mickoleit et al. 2011; Mishima et al. 2006), and Dnd1 can bind to the Uracil-rich region of 3′-UTR of nanos3 to protect the mRNA from miR430-mediated degradation in PGCs (Kedde et al. 2007; Mishima et al. 2006). Thus, the nanos3 3′-UTR has been widely used to mediated PGC-specific gene expression in either transient overexpression experiment or transgenic study (Saito et al. 2006; Xiong et al. 2013).

In this study, by using a combination of the piwil1 promoter and nanos3 3′-UTR, we successfully generated the transgenic zebrafish line, Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg, which could label the whole lifetime of zebrafish germ cells, from early PGCs to oocytes in females and spermatids in males. Furthermore, we carefully traced the development of gonad in fish with different numbers of PGCs from the embryonic stage until adulthood, and proved that the numbers of PGCs became variable at as early as 1 dpf and abundant PGCs at embryonic stage promoted later ovary differentiation and female development.

Materials and Methods

Zebrafish

Embryos were obtained from the natural mating of zebrafish of the AB genetic background (from the China Zebrafish Resource Center, CZRC, Wuhan, China; Web: http://zfish.cn) and maintained, raised, and staged as previously described (Kimmel et al. 1995). The density of fish is 50 larvae/L for age from 5 dpf to 15 dpf, 20 fish/L for age 15 dpf to 1 mpf, 10 fish/L for age from 1 mpf to 2 mpf, and 5 fish/L for age older than 2 mpf. The experiments involving zebrafish were performed under the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Transgenic Construct

We download the genomic sequence of piwil1 from Ensembl (ENSDARG00000041699) and designed the primer pairs to amplify the 5 kb transcriptional regulatory element containing the exon 2 and its upstream sequence according to a previous report (Leu and Draper 2010). The forward primer is 5′-CAAAGAACGAACACCTGGTTGG-3′ and the reverse primer is 5′-ACCGGTGCTTTACAAATGCTGA-3′. The 5-kb fragment was inserted into the upstream of EGFP coding sequence of construct pTol2(EGFP-UTRnanos3) (Kwan et al. 2007; Xiong et al. 2013) to generate the transgenic plasmid, pTol2(piwil1:EGFP-UTRnanos3). The transgenic construct of pTol2(UAS:buc-UTRnanos3) was made based on the pTol2(UAS:mRFP-UTRnanos3) (Xiong et al. 2013). The CDS region of bucky ball (buc) was amplified from zebrafish ovary cDNA and inserted into the pTol2(UAS:mRFP-UTRnanos3) construct to replace the mRFP coding sequence. In-fusion cloning kit (TaKaRa) was used for plasmid construction. All constructs were verified by Sanger sequencing.

Generation of Transgenic Fish

To generate transgenic zebrafish Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3), 50 ng of transgenic construct pTol2(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3) was injected into the animal pole of 1-cell embryo and 100 pg transposase mRNA was injected into the yolk. The F0 embryos were screened under fluorescence stereomicroscope (AF205, Leica). The embryos with bright fluorescence were picked and raised up. The F0 fish were mated with wildtype fish to generate F1 fish. The 2 dpf F1 embryos with bright EGFP-labeled PGCs were selected to raise up. At 14 dpf, the F1 larvae were screened to exclude non-specific EGFP expression at other parts of the body. The F1 adult fish were mated with wildtype fish to generate F2 transgenics. The F2 embryos were also screened at 2 dpf and 14 dpf to exclude non-specific EGFP labeling. Finally, the Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg was established and deposited in CZRC.

The transgenic line Tg(UAS:buc-UTRnanos3)ihb120Tg was generated with a similar method by injection of the pTol2(UAS:buc-UTRnanos3) construct; both F0 and F1 descendants were screened by PCR for the junction of buc and nanos3 3′-UTR with primers listed in Table 1. The transgenic fish Tg(kop:KalTA4-UTRnanos3,CMV:EGFP)ihb8Tg was described in our previous study and obtained from CZRC (catalog ID: CZ20) (Xiong et al. 2013). To obtain PGC-specific buc-overexpressed embryos, we crossed Tg(UAS:buc-UTRnanos3)ihb120Tg males with Tg(kop:KalTA4-UTRnanos3,CMV:EGFP)ihb8Tg females.

Reverse-Transcription Quantitative PCR Analysis

Embryos at 1 dpf were collected for RNA extraction and reverse transcription. The BioRad CFX Connect Real-Time System was used for transcript quantification. Samples were tested in triplicate for each gene, and resultant Cq values were averaged. Primer efficiencies and gene expression levels were calculated according to the previous study (Pfaffl 2001). β-actin was selected as a reference gene. Data was processed using 2−ΔΔCq method. All reverse-transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) gene-specific primers are listed in Table 1.

Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization

Digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probe of zebrafish vasa was synthesized by in vitro transcription. Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) was performed as described (Wei et al. 2014).

Whole-Mount Immunofluorescence

Whole-mount immunofluorescence was performed as described previously with some modifications (Ye and Lin 2013). Incubation of the first antibody was performed at 4 °C overnight. Incubation of secondary antibody was performed at room temperature (23 °C) for 3 h. Samples were immerged in 50% glycerol-PBS at 4 °C overnight before confocal microscopy. The rabbit polyclonal antibody against zebrafish Vasa was used (GTX128306, Gentex, 1:200). Anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 568 was used as secondary antibody (Molecular Probes).

Confocal Microscopy

Transgenic larvae at specific stages were dissected by fine tweezers (5SA-JP, VETUS). The gut and liver were removed to expose the swim bladder. The gonad was just located on both sides of the swim bladder. The swim bladder exposed larvae were fixed in 4% methanol-free PFA at 4 °C overnight. After washing with 1× PBS/Triton X-100 (0.1%), the gonads were isolated under fluorescence stereomicroscope (AF205, Leica). The gonads were stained by phalloidin-Alexa Fluor 568 (Molecular Probes) and DAPI, to visualize F-actin and nuclear DNA, respectively. The gonads were then infiltrated by 50% glycerol-PBS at 4 °C overnight. Confocal images were acquired using a laser-scanning confocal inverted microscope (SP8, Leica) with a LD C-Apo 40×/NA 1.1 water objective. Z-stacks were generated from images taken at 0.5-μm intervals, using the following settings (2048 × 2048 pixel, 400 MHz). EGFP intensity and nuclear diameter were measured by Fiji software (Schindelin et al. 2012). The Cell Counter plugin was used to count the number of oogonia, oocyte IA, and oocyte IB. All data were exported to Excel for statistical analysis. The graphs were generated and the Student t test was performed using GraphPad Prism software.

Results

Lifetime Labeling of Zebrafish Germ Cells in Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg

To specifically label the germ cells from the embryonic stage to adulthood of zebrafish, we generated a transgenic line using piwil1 promoter and nanos3 3′-UTR to direct the expression of EGFP (Fig. 1a). The PGC-specific EGFP could be detected at shield stage in the embryos derived from transgenic females (Fig. 1b). The early specific labeling of PGCs could be due to the combined effects of maternal transcriptional activity of piwil1 and post-transcriptional regulation of nanos3 3′-UTR. However, the transgenic embryos derived from paternal transgenics only showed PGC-specific EGFP expression after 3 dpf (data not shown), which was likely ascribed to the zygotic transcription driven by piwil1 promoter. To our surprise, the transgenic line specifically labeled the germ cell lineage throughout the whole lifetime, i.e., from the PGCs at shield stage to the differentiated gametes at adulthood (Fig. 1b–h). Before 21 dpf, the in vivo development of zebrafish germ cells could be observed under fluorescence microscope (Fig. 1b–e). However, as the fish developed until juvenile stage around 25 dpf, the pigments and adipocyte enriched at the region of gonad; thus, it was difficult to focus the gonad under a microscope. However, the fluorescent gonad could be still seen when the fish was dissected (Fig. 1f). In adult fish, the whole testis showed bright fluorescence while the ovary appeared to show EGFP expression in oogonia and early stage of oocytes (Fig. 1g, h).

Generation and characterization of Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnos3)ihb327Tg. a The structure of the transcriptional regulatory region of piwil1 locus of zebrafish and the sketch map of transgenic elements. b–h Germ cell-specific expression at various developmental stages as indicated in the figure (arrows indicate the EGFP-positive germ cells; outlines indicate the swim bladder). g Dissected adult testis. h Dissected adult ovary (arrows indicate EGFP-positive oogonia or early stage of oocytes). i–k Immunofluorescence of Vasa in the transgenic embryo at 1 dpf. The selected region for imaging is indicated by a red box. i EGFP; j anti-Vasa; k merged channel

To verify that the EGFP specifically labeled the PGCs at the embryonic stage, we performed immunofluorescence using Vasa antibody on transgenic embryos at 1 dpf. As shown in Fig. 1 i–k, the Vasa signals were perfectly co-localized with EGFP, suggesting that the EGFP were exclusively expressed in the PGCs. Taken together, we successfully generate a transgenic line which labels germ cell lineage throughout the whole lifetime of zebrafish.

Early Dimorphic Gonads Lead to Male- or Female-Biased Development

In previous studies, it has been shown that the number of undifferentiated germ cells plays an important role in zebrafish sexual differentiation (Tong et al. 2010; Tzung et al. 2015). To further investigate the correlation of early PGC number and sexual differentiation, we carefully trace the number of PGCs or undifferentiated germ cells from the embryonic stage to larval stage. To accurately count the PGC number at 1 dpf, we utilized optical sectioning of confocal microscopy (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, the embryonic PGC numbers at 1 dpf were variable from 12 to 70 (Fig. 2a, c). We carefully selected the embryos with a low amount of PGCs (less than 25) and the embryos with a high amount of PGCs (more than 36) and raised them in two groups. After the embryos developed after 5 dpf, we took photos for gonads of each group of fish. As expected, the variation on PGC number between the two groups persisted (Fig. 2a) and led to primitive gonads with dimorphic sizes (small gonad and big gonad) at different larval stages (Fig. 2b). These two groups were then raised up and their sex ratios were measured at adulthood. We found that the group with a low amount of PGCs grew up into the male-bias population (80.8% males) while the group with a high amount of PGCs grew up into the female-bias population (72.4% females) (Fig. 2d, data collected from three independent experiments). Taken together, these data reveal that previously unappreciated variation on PGC number occurs at the early embryonic stage, and high amount of PGCs facilitate female differentiation.

Using live tracing to study the correlation between the initial PGC numbers and sexual development. a Representative images of PGC-less and PGC-rich embryos at 1 dpf (a1, a5), 5 dpf (a2, a6), and 7 dpf (a3, a7). b Representative images of PGC-less and PGC-rich larva fish at 11 dpf (b1, b4), 14 dpf (b2, b5), and 20 dpf (b3, b6). c Frequency distribution of PGC number at 1 dpf; two boxes with dashed frame label the selected population of “PGC-less” and “PGC-rich.” The lateral areas of gonads were calculated and were shown at the lower right corner of images in a and b. d The sex ratio in the population of PGC-less and PGC-rich embryos. e Confocal microscopy of small and big gonads at 20 dpf with Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnos3)ihb327Tg transgenic fish. e1 Confocal image of small gonads. e2 Higher magnification of a representative image of small gonad displaying combined channels of DAPI, F-actin, and EGFP. e3 Magnification image showing the nuclei of gonocyte in a small gonad. e4 Confocal image of big gonads. e5, e6 Higher magnification of representative images of big gonads displaying combined channels of DAPI, F-actin, and EGFP. e5 shows an example in which the germ cells have an irregular shape of nuclei; e6 shows an example in which chromatin nucleolus-stage oocytes exist. e7 Magnification image showing cells with irregular shape of nuclei. e8 Magnification image showing that the nuclei of gonocyte were similar to the one in a small gonad

The dimorphic sizes became more obvious at 20 dpf. To carefully examine the cellular characters of both small and big gonads, we performed confocal microscopy (Fig. 2e (e1, e4)). Most of the germ cells in both small and big gonads were gonocytes with a visible nucleolus (Fig. 2e (e3, e8)). Occasionally, stage IA oocytes could be seen in big gonads (Fig. 2(e6) “arrow”). Interestingly, we observed that the nuclei of most germ cells in big gonad were of irregular shape rather than round shape while the nuclei in most of the germ cells in small gonad were round (Fig. 2(e2, e3 e5, e7)). These data suggest that small and big gonads may undergo different morphogeneses of germ cells, leading to a phenotype of gonadal dimorphism from 20 dpf.

Abundance of Early PGCs Promotes Female Development

In the previous study, it has been shown that overexpression of buc generates ectopic germ cells in zebrafish embryos (Bontems et al. 2009). To investigate whether increasing embryonic PGC number would promote the female differentiation, we injected buc mRNA into a zygote and successfully induced more PGCs at shield stage (Fig. 3a, b). The injected embryos were raised up to adulthood and their gender was identified. Interestingly, we found that the ratio of females was significantly higher than that of the uninjected siblings (Fig. 3c), with 74.7% female in buc-overexpressed population vs 50.1% of female in the uninjected siblings. These data strongly suggest that induction of embryonic PGCs promotes female differentiation.

The abundance of early PGCs promotes female development. a Representative images showing PGCs in wildtype and buc-overexpressed embryos at shield stage (PGCS was visualized by WISH). b Percentage of embryos with increased PGCs or normal number of PGCs in wildtype and buc-overexpressed embryos. c Representative images showing PGCs in wildtype and buc-overexpressed embryos at 1 dpf (PGCS was visualized using Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg). d The sex ratio in population of wildtype and buc-overexpressed embryos. e RT-qPCR showing that buc was overexpressed in Tg(kop:KalTA4-UTRnanos3,CMV:EGFP)ihb8Tg/Tg(UAS:buc-UTRnanos3)ihb120Tg double-transgenic fish (dual-Tg) and Tg(UAS:buc-UTRnanos3)ihb120Tg. f The sex ratio in the populations of sibling control (Tg(kop:KalTA4-UTRnanos3,CMV:EGFP)ihb8Tg and wildtype fish), Tg(UAS:buc-UTRnanos3)ihb120Tg and double transgenics

To further verify the above finding, we performed PGC-specific overexpression of buc using Gal4/UAS inductive overexpression method by crossing heterozygote Tg(kop:KalTA4-UTRnanos3,CMV:EGFP)ihb8Tg females with heterozygote Tg(UAS:buc-UTRnanos3)ihb120Tg males. All the offspring with mixed genetic background were raised together in the same tank until adulthood. Their genotypes and genders were individually identified either by PCR or by expression of EGFP. To verify that buc was overexpressed in the double transgenics, we performed RT-qPCR analysis on 1 dpf embryos of double-transgenic fish and Tg(UAS:buc-UTRnanos3)ihb120Tg using the primer pairs amplify the region covering the junction of buc and nanos3 3′-UTR (buc-UTRnanos3) (Fig. 3d). The expression of both the coding region of buc and the junction of buc-UTRnanos3 was remarkably increased in the Tg(UAS:buc-UTRnanos3)ihb120Tg or double-transgenic fish when compared with the wildtype siblings (Fig. 3d). Similar to the result from buc injection, the double-transgenic siblings showed female bias compared to wildtype siblings (Fig. 3e), and the Tg(UAS:buc-UTRnanos3)ihb120Tg siblings also showed pro-female development, due to the reason that the maternally deposited Gal4 proteins in the eggs of heterozygote Tg(kop:KalTA4-UTRnanos3) female could activate the buc expression in Tg(UAS:buc-UTRnanos3)ihb120Tg embryos. Taken together, our data demonstrate that abundant embryonic PGCs facilitate the female differentiation.

Ovary Development in Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg

The development of ovary from 25 to 50 dpf was carefully assessed using Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg. A few stage IB oocytes started to be visible in big gonad at 25 dpf (Fig. 4a (a1)). There were mainly oogonia, stage IA oocyte, and stage IB oocyte in the ovary from 25 to 40 dpf (Fig. 4a–d (a1–d1)). From middle to late stage of IB oocytes, the Balbiani body could not be stained by DAPI and formed a dark dot (Fig. 4(c1, d1) asterisk). As shown in Fig. 4 e, from 25 to 35 dpf, the percentage of oogonia decreased while the percentage of stage IA and stage IB oocytes increased, suggesting proceeding of oogenesis from oogonia to stage I oocyte. From 35 to 40 dpf, the portion of each cell type was fairly stable (Fig. 4e). At 40 dpf, oocytes transiting from stage IB to stage II began to be visible (Fig. 4d (d1)). Strikingly, at 45 dpf, most of the stage IB oocytes started to develop into stage II oocytes in a simultaneous manner (Fig. 4f). At 50 dpf, the stage II oocytes started to be visible which were marked by thick cortical actin and robust increasing of cortical alveolus (Fig. 4g). It was worth noting that the EGFP was persistently expressed in oogonia from 25 dpf to 3 mpf (Fig. 4a–h). Thus, the whole process of ovary development can be visualized at intact-gonad level with high resolution using Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg.

Confocal microscopy of ovary development. a–h Confocal images of developing ovaries at 25 dpf (a), 30 dpf (b), 35 dpf (c), 40 dpf (d), 45 dpf (e), 50 dpf, and 3 mpf (f). a1, b1, c1, d1, and h1 are the magnified regions of interest in a, b, c, d, and h respectively. e The graph showing the percentage of oogonia, stage IA oocyte, and stage IB oocyte in ovaries of 26 dpf, 30 dpf, 35 dpf, and 40 dpf. Arrows in a1 indicate the oogonia (Og), stage IA oocyte (IA), and stage IB oocyte (IB); asterisk in c1 and d1 indicates the Balbiani body; arrow in h1 indicates the oogonia

Testis Development in Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg

The development of testis from 25 dpf to 50 dpf was carefully assessed using Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg. Unlike the small gonad at 21 dpf, the germ cells in the small gonad at 25 dpf were mainly different subtypes of spermatogonia with different nuclear sizes and fluorescent intensities, indicating proceeding of spermatogenesis at this stage (Fig. 5a (a1–a3)). The degeneration of oocytes occurred at 30 dpf and ended at 40 dpf (Fig. 5b–d (b1)). Unlike that the oocytes which were surrounded by follicle cells, the germ cells in testis aggregated into cell clusters (Fig. 5a–f). Strikingly, spermatid could be seen at as early as 45 dpf, indicating that the whole process of spermatogenesis has completed at this time (Fig. 5e). At 50 dpf, testis developed morphologically identified tubular compartment which contained germ cells of different stages of spermatogenesis (Fig. 5f).

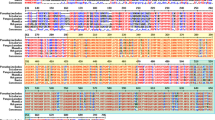

Confocal microscopy of testis development. a–d Confocal images of developing testes at 25 dpf (a), 30 dpf (b), 35 dpf (c), and 40 dpf (d). Arrows in b, c, and d indicate the degenerating oocytes. a1–a3 are the magnified regions of interest labeling 1 to 3, respectively, in a; b1 is the magnified region of interest labeling 1 in b. a1–a3 Representative image showing EGFP-positive early spermatogonia (a1), EGFP-positive early spermatogonia of Pachytene stage (a2), and weak EGFP in late spermatogonia (a3) in a. b1 Representative image showing degenerating oocyte in b. e–f Confocal images of developing testes at 45 dpf (e) and 50 dpf (f). e1–e8 are the magnified regions of interest labeling 1 to 8, respectively, in e. e1–e8 Representative images showing early spermatogonia (e1), late spermatogonia (e2), primary spermatocyte at leptotene/zygotene stage (e3), primary spermatocyte at pachytene stage (e4), secondary spermatocyte (e5), early spermatid (e6), late spermatid (e7), and primary spermatocyte at metaphase I (e8). g Graph showing EGFP intensity of various types of spermatogenic cells in e. h Graph showing the nuclear diameter of various types of spermatogenic cells in e. The left, middle, and right images in a1–a3 and b1 showed DAPI, F-actin, and EGFP, respectively; upper row in e1–e8: DAPI; lower row in e1–e8: EGFP; Asterisk indicates P value < 0.01

Visualization of the process of testis development and specific labeling of germ cells by Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg provided us an opportunity to identify different cell types in intact gonads during spermatogenesis. The different germ cell stages during spermatogenesis are generally divided into main four classes—spermatogonia, primary spermatocytes, secondary spermatocytes, and spermatid (Schulz et al. 2010). We carefully measured diameters of cell nuclei and intensities of different germ cells to characterize germ cells of different developmental stages from 45 dpf (Fig. 5 e(e1–e8)).

Based on both nuclear morphology and EGFP intensity of germ cells on a 45 dpf testis, there are two subtypes of spermatogonia—one with less number and higher EGFP intensity, whereas the other with more cells but lower EGFP intensity. However, there is no significant difference in nuclear diameter between early and late stages of spermatogonia (Fig. 5 e(e1, e2)). Our observation indicates that the spermatogonia with lower EGFP intensity is at a later stage and the one with higher EGFP intensity is at an earlier stage which might be the type A spermatogonia. As meiotic prophase proceeded, the intensity of EGFP increased and reached a peak at an early stage of spermatid, and the average intensity decreased but become aggregated in the late stage of spermatid (Fig. 5 e(e3–e8), g, h). Taken together, the early development of testis and spermatogenesis can be characterized in details at intact-gonad level using Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg.

To verify whether the EGFP intensity can be used as a reliable indicator for identification of germ cells at different stages in the matured testis, we performed an analysis in the testis of adult zebrafish at 5 mpf (Fig. 6a). Consistently, we could identify early and late spermatogonia based on their EGFP intensities (Fig. 6b, c). The expression of EGFP also increased during the meiotic prophase and reached the highest expression at secondary spermatocytes (Fig. 6d–h). More interestingly, we found that the EGFP aggregated to the posterior region of the head of spermatozoa and specifically labeled its tail (Fig. 6i, j). Taken together, using EGFP intensity as a criterion, we could easily identify the germ cells at different stages during spermatogenesis in the Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg.

Confocal microscopy of adult testis. a Confocal image of adult testis. b–j The magnified regions of interest in a; b–j Representative images showing early spermatogonia (b), late spermatogonia (c), primary spermatocyte at leptotene/zygotene stage (d), primary spermatocyte at late leptotene/zygotene stage based on the EGFP intensity (e), primary spermatocyte at pachytene stage (f), primary spermatocyte at metaphase I (g), secondary spermatocyte (h), spermatid (i), and spermatozoa (j). Upper row in b–j: DAPI; lower row in b–j: EGFP

Discussion

Transgenic labeling of germ cells by fluorescent proteins provides us with a powerful tool to study the germ cell development and gonad differentiation of teleost. In the present study, we have successfully generated a transgenic zebrafish line Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg, in which the lifetime germline could be specifically and efficiently labeled for the first time. By using this transgenic line, we were able to visualize the lifetime development of zebrafish germline and to analyze the relationship between initial embryonic PGC number and the later gonad differentiation.

In the previous studies, although different types of germ cells at different stages have been labeled by various transgenic zebrafish, none of them could label the whole lifetime of zebrafish germline. For instance, a similar transgenic line, Tg(piwil1:EGFP)uc1Tg could label the germline from 7 dpf but not the embryonic PGCs before that, probably due to that a different SV40 polyA signal was used in their study (Leu and Draper 2010). In our transgenic fish, the use of piwil1 promoter ensures the maternal expression of EGFP and the use of 3′-UTR of nanos3 ensure its restricted expression in PGCs. Thus, the embryonic PGCs could be labeled as early as the shield stage. During spermatogenesis, unlike the Tg(piwil1:EGFP)uc1Tg, which showed highest EGFP expression level in spermatogonia (Leu and Draper 2010), our Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg displayed different expression levels in different types of spermatogenic cells, with a relatively high level in spermatocyte and spermatid. Considering that the Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg has specific expression pattern on labeling different types of germ cells particularly the germline stem cells, it will be of great interest to use this transgenic fish to identify and sort out the early type A spermatogonia, oogonia, and PGCs combining the usage of fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS) in the future. Those sorted germline stem cells can be used not only for transcriptome analysis but also for research on surrogate reproduction (Morita et al. 2015).

It is reported that the number of PGCs plays critical roles in sexual development and the depletion of PGCs usually results in infertile male in some fish species such as zebrafish, medaka, and Carassius gibelio (Kurokawa et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2015; Siegfried and Nusslein-Volhard 2008). However, there is no report of the effects of early germ cell induction on later sex differentiation. In our present study, we utilized the Tg(piwil1:egfp-UTRnanos3)ihb327Tg transgenic line to unveil that rich embryonic PGC number led to later ovary differentiation and female development and less embryonic PGC number resulted in later male development. More interestingly, we utilized the method of buc overexpression (Distel et al. 2009), by either transient overexpression with mRNA injection or stable overexpression with Gal4/UAS transgenic system (Xiong et al. 2013) to induce ectopic PGCs at shield stage. The induction of PGCs at shield stage could also promote female differentiation. All these data demonstrate that the initial number of PGCs should greatly contribute to the sex differentiation in zebrafish. In the future, it will be interesting to test whether different amounts of germplasm exist in different oocytes and which mechanism is responsible for this type of germplasm variation. Since the Gal4/UAS system has been successfully utilized for PGC-specific overexpression of buc which leads to female-biased development, it might have great application in female-biased breeding by induction of female development in some commercial fish species with sexual growth dimorphism (Mei and Gui 2015).

References

Blaser H, Eisenbeiss S, Neumann M, Reichman-Fried M, Thisse B, Thisse C, Raz E (2005) Transition from non-motile behaviour to directed migration during early PGC development in zebrafish. J Cell Sci 118:4027–4038

Bontems F, Stein A, Marlow F, Lyautey J, Gupta T, Mullins MC, Dosch R (2009) Bucky ball organizes germ plasm assembly in zebrafish. Curr Biol 19:414–422

Distel M, Wullimann MF, Koster RW (2009) Optimized Gal4 genetics for permanent gene expression mapping in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:13365–13370

Draper BW, McCallum CM, Moens CB (2007) nanos1 is required to maintain oocyte production in adult zebrafish. Dev Biol 305:589–598

Houwing S et al (2007) A role for Piwi and piRNAs in germ cell maintenance and transposon silencing in Zebrafish. Cell 129:69–82

Kedde M et al (2007) RNA-binding protein Dnd1 inhibits microRNA access to target mRNA. Cell 131:1273–1286

Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF (1995) Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn 203(3):253–310

Kosaka K, Kawakami K, Sakamoto H, Inoue K (2007) Spatiotemporal localization of germ plasm RNAs during zebrafish oogenesis. Mech Dev 124:279–289

Krovel AV, Olsen LC (2002) Expression of a vas::EGFP transgene in primordial germ cells of the zebrafish. Mech Dev 116:141–150

Krovel AV, Olsen LC (2004) Sexual dimorphic expression pattern of a splice variant of zebrafish vasa during gonadal development. Dev Biol 271:190–197

Kurokawa H, Saito D, Nakamura S, Katoh-Fukui Y, Ohta K, Baba T, Morohashi KI, Tanaka M (2007) Germ cells are essential for sexual dimorphism in the medaka gonad. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:16958–16963

Kwan KM, Fujimoto E, Grabher C, Mangum BD, Hardy ME, Campbell DS, Parant JM, Yost HJ, Kanki JP, Chien CB (2007) The Tol2kit: a multisite gateway-based construction kit for Tol2 transposon transgenesis constructs. Dev Dyn 236:3088–3099

Lau ES, Zhang Z, Qin M, Ge W (2016) Knockout of Zebrafish ovarian aromatase gene (cyp19a1a) by TALEN and CRISPR/Cas9 leads to all-male offspring due to failed ovarian differentiation. Sci Rep 6:37357

Leu DH, Draper BW (2010) The ziwi promoter drives germline-specific gene expression in zebrafish. Dev Dyn 239:2714–2721

Lewis ZR, McClellan MC, Postlethwait JH, Cresko WA, Kaplan RH (2008) Female-specific increase in primordial germ cells marks sex differentiation in threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus). J Morphol 269:909–921

Li Q, Fujii W, Naito K, Yoshizaki G (2017) Application of dead end-knockout zebrafish as recipients of germ cell transplantation. Mol Reprod Dev 84:1100–1111

Liew WC, Bartfai R, Lim Z, Sreenivasan R, Siegfried KR, Orban L (2012) Polygenic sex determination system in zebrafish. PLoS One 7:e34397

Liu W, Li SZ, Li Z, Wang Y, Li XY, Zhong JX, Zhang XJ, Zhang J, Zhou L, Gui JF (2015) Complete depletion of primordial germ cells in an all-female fish leads to sex-biased gene expression alteration and sterile all-male occurrence. BMC Genomics 16:971

Maack G, Segner H (2003) Morphological development of the gonads in zebrafish. J Fish Biol 62:895–906

Mei J, Gui J-F (2015) Genetic basis and biotechnological manipulation of sexual dimorphism and sex determination in fish. Sci China Life Sci 58:124–136

Mickoleit M, Banisch TU, Raz E (2011) Regulation of hub mRNA stability and translation by miR430 and the dead end protein promotes preferential expression in zebrafish primordial germ cells. Dev Dyn 240:695–703

Mishima Y, Giraldez AJ, Takeda Y, Fujiwara T, Sakamoto H, Schier AF, Inoue K (2006) Differential regulation of germline mRNAs in soma and germ cells by zebrafish miR-430. Curr Biol 16:2135–2142

Morita T, Morishima K, Miwa M, Kumakura N, Kudo S, Ichida K, Mitsuboshi T, Takeuchi Y, Yoshizaki G (2015) Functional sperm of the yellowtail (Seriola quinqueradiata) were produced in the small-bodied surrogate, Jack mackerel (Trachurus japonicus). Mar Biotechnol 17:644–654

Onichtchouk D, Aduroja K, Belting HG, Gnugge L, Driever W (2003) Transgene driving GFP expression from the promoter of the zona pellucida gene zpc is expressed in oocytes and provides an early marker for gonad differentiation in zebrafish. Dev Dyn 228:393–404

Payne-Ferreira TL, Tong KW, Yelick PC (2004) Maternal alk8 promoter fragment directs expression in early oocytes. Zebrafish 1:27–39

Pfaffl MW (2001) A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29:e45

Rodriguez-Mari A, Yan YL, Bremiller RA, Wilson C, Canestro C, Postlethwait JH (2005) Characterization and expression pattern of zebrafish anti-Mullerian hormone (Amh) relative to sox9a, sox9b, and cyp19a1a, during gonad development. Gene Expr Patterns 5:655–667

Rodriguez-Mari A, Canestro C, Bremiller RA, Nguyen-Johnson A, Asakawa K, Kawakami K, Postlethwait JH (2010) Sex reversal in zebrafish fancl mutants is caused by Tp53-mediated germ cell apoptosis. PLoS Genet 6:e1001034

Saito T, Fujimoto T, Maegawa S, Inoue K, Tanaka M, Arai K, Yamaha E (2006) Visualization of primordial germ cells in vivo using GFP-nos1 3′ UTR mRNA. Int J Dev Biol 50:691–700

Saito D, Morinaga C, Aoki Y, Nakamura S, Mitani H, Furutani-Seiki M, Kondoh H, Tanaka M (2007) Proliferation of germ cells during gonadal sex differentiation in medaka: insights from germ cell-depleted mutant zenzai. Dev Biol 310:280–290

Saito T, Goto-Kazeto R, Arai K, Yamaha E (2008) Xenogenesis in teleost fish through generation of germ-line chimeras by single primordial germ cell transplantation. Biol Reprod 78:159–166

Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez JY, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A (2012) Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9:676–682

Schulz RW, de Franca LR, Lareyre JJ, Le Gac F, Chiarini-Garcia H, Nobrega RH, Miura T (2010) Spermatogenesis in fish. Gen Comp Endocrinol 165:390–411

Siegfried KR, Nusslein-Volhard C (2008) Germ line control of female sex determination in zebrafish. Dev Biol 324:277–287

Tong SK, Hsu HJ, Chung BC (2010) Zebrafish monosex population reveals female dominance in sex determination and earliest events of gonad differentiation. Dev Biol 344:849–856

Tzung KW, Goto R, Saju JM, Sreenivasan R, Saito T, Arai K, Yamaha E, Hossain MS, Calvert MEK, Orbán L (2015) Early depletion of primordial germ cells in zebrafish promotes testis formation. Stem Cell Rep 4:61–73

Uchida D, Yamashita M, Kitano T, Iguchi T (2002) Oocyte apoptosis during the transition from ovary-like tissue to testes during sex differentiation of juvenile zebrafish. J Exp Biol 205:711–718

Wang XG, Bartfai R, Sleptsova-Freidrich I, Orban L (2007) The timing and extent of ‘juvenile ovary’ phase are highly variable during zebrafish testis differentiation. J Fish Biol 70:33–44

Wei CY, Wang HP, Zhu ZY, Sun YH (2014) Transcriptional factors Smad1 and Smad9 act redundantly to mediate zebrafish ventral specification downstream of Smad5. J Biol Chem 289:6604–6618

Xiong F, Wei ZQ, Zhu ZY, Sun YH (2013) Targeted expression in zebrafish primordial germ cells by Cre/loxP and Gal4/UAS systems. Mar Biotechnol 15:526–539

Yang YJ, Wang Y, Li Z, Zhou L, Gui JF (2017) Sequential, divergent, and cooperative requirements of Foxl2a and Foxl2b in ovary development and maintenance of Zebrafish. Genetics 205:1551–1572

Ye D, Lin F (2013) S1pr2/Galpha13 signaling controls myocardial migration by regulating endoderm convergence. Development 140:789–799

Acknowledgements

We thank Kuoyu Li from China Zebrafish Resource Center (CZRC) for taking care of the zebrafish. We thank Fang Zhou from the Analysis and Testing Center of Institute of Hydrobiology, CAS, for the technical support of confocal imaging.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (grant no: 2018YFD0901205), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31721005 and 31872550), Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no: XDA08010106), and Projects from State Key Laboratory of Freshwater Ecology and Biotechnology (grant nos. 2016FBZ03, 2015FB11).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, D., Zhu, L., Zhang, Q. et al. Abundance of Early Embryonic Primordial Germ Cells Promotes Zebrafish Female Differentiation as Revealed by Lifetime Labeling of Germline. Mar Biotechnol 21, 217–228 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10126-019-09874-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10126-019-09874-1