Abstract

Background

The optimal surgical approach for adenocarcinoma directly at the esophagogastric junction (AEG II) is still under debate. This study aims to evaluate the differences between right thoracoabdominal esophagectomy (TAE) (Ivor–Lewis operation) and transhiatal extended gastrectomy (THG) for AEG II.

Methods

From a prospective database, 242 patients with AEG II (TAE, n = 56; THG, n = 186) were included and analyzed according to characteristics and perioperative morbidity and mortality and overall survival (chi-square, Mann–Whitney U, log-rank, Cox regression).

Results

Groups were comparable at baseline with exception of age. Patients older than 70 years were more frequently resected by THG (p = 0.003). No differences in perioperative morbidity (p = 0.197) and mortality (p = 0.711) were observed, including anastomotic leakages (p = 0.625) and pulmonary complications (p = 0.494). There was no significant difference in R0 resection (p = 0.719) and number of resected lymph nodes (p = 0.202). Overall median survival was 38.4 months. Survival after TAE was significantly longer than after THG (median OS not reached versus 33.6 months, p = 0.02). Multivariate analysis revealed pN-category (p < 0.001) and type of surgery (p = 0.017) as independent prognostic factors. The type of surgery was confirmed as prognostic factor in locally advanced AEG II (cT 3/4 or cN1), but not in cT1/2 and cN0 patients.

Conclusions

Our single-center experience suggests that patients with (locally advanced) AEG II tumors may benefit from TAE compared to THG. For further evaluation, a randomized trial would be necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The worldwide incidence of esophageal cancer has been increasing in the past decades. The rise is mainly triggered by an increase of adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction (AEG) [1, 2]. This entity is classified according to Siewert into three types with respect to localization relative to the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) [3]. Although AEG I are adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus with the center located within 1 and 5 cm above the anatomic EGJ [4], AEG type II tumors are considered “true” cardia carcinomas with a tumor center within 1 cm above and 2 cm below the EGJ and with components of both gastric and esophageal carcinomas [5]. AEG type III tumors arise from the gastric mucosa [6]. Because of a higher frequency of involvement of thoracic lymph nodes in AEG I, the common surgical approach to these tumors is a thoracoabdominal esophagectomy (TAE) [7]. For AEG III tumors, transhiatal extended gastrectomy (THG) is proposed as the method of choice [8]. The optimal surgical strategy for AEG type II tumors remains unclear, some authors preferring an abdominal approach with THG, and other authors preferring a TAE [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. In addition there are different possibilities for the surgical approach for TAE. In Western countries the standard approach is a right-sided thoracotomy (Ivor–Lewis procedure), whereas in Asian countries the approach is done by a left-sided thoracotomy. Some authors have postulated that TAE is more invasive, resulting in more complications and a longer hospital stay as well as in reduced quality of life [16, 17]. Still more important is to investigate the impact on prognosis. Thus far, the question whether survival of patients with AEG II is better after esophagectomy or after extended gastrectomy remains unsolved.

The standard of care for locally advanced AEG II in Europe is perioperative chemotherapy [18, 19] or neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy [20,21,22]. Both treatment regimens have been shown to improve prognosis in comparison to surgery alone. However, no data exist favoring one approach over another [23]. Thus, there are multiple open questions regarding the optimal treatment for AEG II tumors with respect to perioperative treatment and surgical concepts.

The aim of this study is to analyze the perioperative as well as the long-term outcome of patients with AEG II undergoing either TAE or THG in our center. To our knowledge, this study is the largest series including exclusively AEG II patients.

Materials and methods

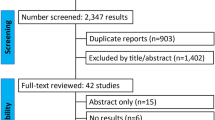

The analysis is performed from an institutional, prospectively maintained database including n = 1289 patients with carcinoma of the esophagus or stomach having been treated in the Department of Surgery at the University of Heidelberg from 2001 to 2015.

Inclusion criteria were AEG II (tumor center within 1 cm proximal and 2 cm distal of the EGJ) resected with curative intent. Patients who only underwent exploratory laparotomy or palliative surgery were excluded from the analysis.

Approval was obtained from the institutional Ethics Review Board of the University of Heidelberg.

Preoperative staging

Preoperative staging included computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis as well as upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with biopsies for histopathological confirmation of diagnosis and an additional endoscopic ultrasound in most of the patients. The diagnosis of an AEG II was done endoscopically, but diagnosis was confirmed intraoperatively. Patients for whom diagnosis of an AEG II could not be confirmed during surgery were not included in the analysis.

Surgery

Tumor resection was performed with either a thoracoabdominal approach via a median laparotomy and a right-sided thoracotomy for esophagectomies (Ivor–Lewis procedure) [24] or an abdominal approach with median laparotomy for transhiatal extended gastrectomies with distal esophagus resection. Regular reconstruction for TAE was done by gastric tube construction and esophagogastrostomy [25, 26], alternatively by fundus rotation gastroplasty [27, 28] and end-to-side circular stapler anastomosis at the level of the azygous vein. In cases in which a gastric tube or fundus rotation gastroplasty was not feasible, reconstruction was done by colon interposition in two cases and esophagojejunostomy in one case. For THG in addition to total gastrectomy, the hiatus of the diaphragm was split to perform a distal esophagectomy as well as a lymphadenectomy in the lower mediastinum. Reconstruction was done by esophagojejunostomy (with localization in the lower mediastinum) and Roux-en-Y anastomosis.

Lymphadenectomy was performed according to current guidelines [29] including a D2-lymphadenectomy and a dissection of the lymph nodes of the lower mediastinum in THG and a two-field lymphadenectomy in TAE.

The decision for one procedure over the other was taken preoperatively according to preoperative diagnostic findings or in some cases intraoperatively by the surgeon. There were no systematic tools for decision making. A bias arising from a patient’s condition cannot be ruled out.

Perioperative treatment

In locally advanced tumors, neoadjuvant treatment was recommended as the standard of care after 2006 to all patients with locally advanced tumors; there were some patients who still preferred primary resection. In total, 120 patients were treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy; of those, 118 patients met the criteria for a locally advanced carcinoma (cT 3/4 or cN+). For 2 patients, information about exact clinical staging was missing, and for 17 patients the preoperative treatment was discontinued prematurely because of toxicity or nonresponse.

The remaining 122 patients were primarily resected. Table 1 summarizes types of preoperative treatment regimens. We could not find any differences between the two study groups.

Histopathological assessment

The histopathological workup was done by pathologists experienced in upper gastrointestinal tract carcinomas. Tumors were classified according to the TNM classification, 7th edition (2010). Tumors of patients having been treated before 2010 were reclassified according to the new TNM classification. Histopathological response was graded according to Becker et al. [30,31,32].

Perioperative complications

Perioperative complications were assessed prospectively and retrospectively classified according to Clavien–Dindo [33].

Follow-up

Most patients were followed on an outpatient basis in the National Center for Tumor Disease (NCT) in Heidelberg. If patients decided to be followed elsewhere, they were contacted by phone to obtain follow-up data.

According to the actual German guidelines (S3 Leitlinie), a systematic follow-up with a specified follow-up schedule and routine diagnostic is not recommended. Therefore, for some patients follow-up diagnostics were only performed in case of symptoms. Patients who were followed in the NCT Heidelberg were followed regularly every 3 months during the first year, every 6 months during the second and third, year and once per year thereafter until a follow-up of 5 years.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done with IBM SPSS statistics 18.0 (Mac). Continuous variables are presented as median (range) and compared with the Mann–Whitney U test; ordinal values are compared with the chi-square test. Survival is counted from time of diagnosis to death, survival curves are estimated with the Kaplan–Meier-method, and difference in survival is tested by the log-rank-test. A p value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Univariate and multivariate analysis was done by the Cox stepwise proportional hazard model (forward conditional hazard model). The backward conditional hazard model was used for confirmation of independent prognostic factors. Significant univariate factors as well as all factors with p < 0.2 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis.

Results

Of the patients, 242 patients with AEG II were identified in our prospectively kept database, of whom 56 (23.1%) underwent TAE (n = 43 gastric tube reconstruction, n = 10 fundus rotation gastroplasty, n = 2 colon interposition, n = 1 esophagojejunostomy) and 186 (76.9%) had a THG with esophagojejunostomy in the lower mediastinum and reconstruction with Roux-en-Y anastomosis.

Preoperative patient characteristics according to the two surgical procedures are presented in Table 2a. Patient groups were comparable at baseline with the exception of age.

Patients older than 70 years were more often resected by THG (p = 0.003). Clinical staging did not differ between the gastrectomy group and the esophagectomy group.

The length of esophageal invasion of the tumor did not differ significantly between the two treatment groups (p = 0.241). Median length of the esophagus of the THG group was 0.9 cm (range, 0–8.4 cm), and that of the TAE group, 1.5 cm (range, 0–13 cm).

Also, no difference could be found for the ASA classification, patients with severe comorbidities, or the percentage of patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy. Of the patients with cT3/4 or cT2 and positive lymph nodes, 55.8% in the THG group and 66.0% in the TAE group were treated by neoadjuvant chemotherapy (p = 0.215). Patients who did not undergo neoadjuvant treatment despite locally advanced tumor stage were either resected before 2006 or were primarily resected according to medical reasons or patients’ wish.

Complications (including minor and major complications) occurred in 47.3% after THG and in 57.1% after TAE (p = 0.197). Overall, there was no difference in complication rates, especially no significant difference in anastomotic leakage (11.8% THG versus 14.3% TAE, p = 0.625) or pulmonary complications (28.2% versus 33.3%, p = 0.494) and cardiac complications (16.0% versus 25.5%, p = 0.133). Furthermore, severe complications (Clavien–Dindo >3a) were comparable in both groups (19.4% versus 28.6%, p = 0.141). The 30-day mortality and in-hospital mortality did not differ (2.7%/4.5% versus 5.4%/5.4%; p = 0.711).

Patients after gastrectomy were hospitalized for a median of 15 days, whereas patients after esophagectomy had a median hospital stay of 19 days (p = 0.004) (Table 2b).

Most patients had (y)pT3 tumors (60.2% THG, 46.4% TAE), and the majority had lymph node metastases (71.0% THG, 66.1% TAE). Complete tumor resection (R0 category) could be achieved in 83.9% in the gastrectomy group and 85.9% in the esophagectomy group (p = 0.719). Distant metastases were present in 12.9% (THG) and 8.9% (TAE) (p = 0.422). Resection of distant metastasis was done in an individual curative concept in respect of young age and excellent performance status after a good clinical response to preoperative treatment as before [34]. Of the patients with metastatic disease, 50% (THG) and 60% (TAE) underwent a complete tumor resection (p = 0.684). The median number of resected lymph nodes was 24 in both groups; there was no significant difference in the lymph node ratio (positive/resected lymph nodes) (p = 0.202) (Table 2c).

Survival

Overall median survival (MS) for all patients was 38.4 months (95% CI, 27.4; 49.5) with a 3-year survival of 53.0% and a 5-year survival of 42.8%.

Median follow-up of the surviving patients was 42.4 months.

Patients after THG had significant shorter survival times than patients after TAE (MS 33.6 months after THG, 95% CI, 23.8; 43.4, versus not reached after TAE, p = 0.02). The 3- and 5-year survival rates were significantly lower (48.5% versus 69.6%; 38.8% versus 57.5%; p = 0.02) (Fig. 1a).

Also, disease-specific survival differed significantly after THG and TAE (3- and 5-year survival, 54.5% and 44.8% after THG versus 87.6% and 79.1% after TAE, MS 44.2 months after THG (95% CI, 30.0; 58.5) versus not reached after TAE, p = 0.002).

Significant prognostic factors for survival by univariate analysis were age (p = 0.016), cT-category (p = 0.018), cN-category (p = 0.006), pT-category (p = 0.030), and pN-category (p < 0.001), distant metastasis (p = 0.005), and R-status (p = 0.01). Neoadjuvant treatment in case of cT3/4, cN(any) or cTany cN+ resulted in better survival (p = 0.024). Pathological response (Becker regression score) had no significant impact on survival times.

Multivariate analysis by Cox proportional hazard model was done in the cohort of patients younger than 70 years, as only a few older patients were resected by TAE. Multivariate analysis including all univariate significant factors (and all factors with p < 0.2) revealed pN-category (p < 0.001), pT-category (p = 0.031), and type of surgery (p = 0.005) as independent prognostic factors. Hazard ratio for death for THG versus TAE was 2.5 (95% CI, 1.3; 4.7), Table 3.

As the decision for the type of surgery has to be made before knowing the exact pathological staging, a subgroup analysis for the impact on survival of THG versus TAE was performed according to the clinical staging. The prognostic impact of type of surgery was present in locally advanced tumors according to clinical staging (cT3/4, p = 0.018 and cN1, p = 0.006), but not for cT1/2, p = 0.941 and cN0 patients, p = 0.720 (Fig. 2a–d). As usually only patients with locally advanced tumors undergo a neoadjuvant therapy, the type of surgery only was a significant prognostic factor in patients after neoadjuvant therapy (p = 0.004) (Fig. 3).

a Survival according to the type of surgery in cT1/2 patients (p = 0.558). b Survival according to the type of surgery in cT3/4 patients (p = 0.018). c Survival according to the type of surgery in cN0 patients (p = 0.586). d Survival according to the type of surgery in cN1 patients (p = 0.003). TAE thoracoabdominal esophagus resection, THG transhiatal extended gastrectomy

Additional survival analysis was performed for patients who were younger than 70 years, as only 6 patients older than 70 years were resected by TAE. In the subgroup of the patients younger than 70 years survival also differed significantly between THG and TAE (3- and 5-year survival, 51.5% and 40.1% after THG versus 71.8% and 60.2% after TAE, MS 37.5 months (95% CI, 29.8;45.4) versus not reached, p = 0.043).

Considering only patients without distant metastasis (M0) and complete tumor resection (R0) as the subgroup of patients with a complete and curative surgery, survival did also differ between THG and TAE: 3- and 5-year survival, 56.2% and 44.9% versus 75.9% and 63.0%, MS 41.8 months after THG (95% CI, 28.6;55.0) versus MS not reached after AT, p = 0.046 (Fig. 1b).

Recurrence rate after THG was 46.5% versus 29.7% after TAE (p = 0.069). Local recurrence rate did not differ significantly (17.1% versus 12.8%, p = 0.528), nor did recurrence of lymph node metastasis (10.9% and 11.4%, p = 0.927), distant metastasis (31.9% and 18.2%, p = 0.08), or peritoneal carcinomatosis (9.6% and 2.3%, p = 0.117).

Median recurrence time after THG was 22.4 months (95% CI, 10.5; 34.2); median recurrence time after TAE was not reached (p = 0.018).

Discussion

This study was performed to evaluate the optimal surgical approach for AEG II. Despite multiple studies [8, 35,36,37,38,39,40], the discussion is still ongoing whether the “true” carcinoma of the cardia should be resected in accordance to a carcinoma of the esophagus or stomach. Most of the studies are of a heterogeneous design, summarizing different surgical approaches under esophagectomy and gastrectomy and including not only AEG II but AEG I–III.

In our department patients with AEG II were resected either by thoracoabdominal esophagectomy by right-sided approach (Ivor–Lewis procedure) or by gastrectomy with transhiatal extension and resection of the distal esophagus. No standardized selection criteria were in place to define which operation was performed on which patient. Patients were comparable at baseline including tumor stage, ASA classification, and comorbidities. However, we cannot rule out a selection bias as fewer patients older than 70 years underwent a thoracoabdominal approach. Previously we have shown that age does not influence survival in our patient cohort [41], yet in this cohort patients who were older than 70 years at the time of diagnosis had shorter survival times. As only a few patients older than 70 years were resected by TAE, we performed a subgroup analysis including only patients younger than 70 years for better comparability, confirming the prognostic influence of the type of surgery for this subgroup, and we identified the type of surgery as an independent prognostic factor in multivariate analysis in the cohort of patients younger than 70 years.

However, because of the individually planned surgical strategy for each patient and the nonrandomized design, we cannot exclude unequal distribution of yet unknown confounders. Additionally, the localization and definition of AEG II were made preoperatively based on the endoscopy results and confirmed intraoperatively. The definition of the exact tumor center is difficult and potentially subjective, but remains a clinical problem with which surgeons have to cope when planning the operative procedure.

Some authors claim that TAE is more invasive and consequently results in more postoperative complications and a higher postoperative mortality [8]; pulmonary complications especially seem more frequent [24]. We were unable to demonstrate a difference in perioperative morbidity and mortality between the two procedures, in line with results from other studies [37, 38, 40].

We included reconstruction with gastric tube as well as fundus rotation gastroplasty for TAE in this analysis. Actual standard reconstruction for TAE is gastric tube in our department. A subgroup analysis only for fundus rotation gastroplasty was not possible because sample size was limited (n = 10). However, survival analysis was performed for THG versus TAE with gastric tube reconstruction, confirming longer survival times after TAE (p = 0.002).

The thoracoabdominal approach leads to a more extensive lymphadenectomy in the mediastinum as well as to larger proximal safety margins and seems therefore oncologically more radical. Barbour et al. demonstrated that patients with AEG with a proximal safety margin of more than 3.8 cm on the resected specimen had a better prognosis. Surgical margins were significantly greater by esophageal resection than by extended gastrectomy, which in turn resulted in better survival times [35]. Also, other authors suggest a resection margin of 5–8 cm in situ as a safe surgical margin [39, 42]. The survival benefit of TAE in our patients’ cohort can possibly be the result of this greater surgical margin after TAE also if the rate of R0 resections did not differ between the two groups.

Another important prognostic factor in esophagogastric adenocarcinoma is the presence and number of tumor-positive lymph nodes, which was confirmed by our data as the pN-category presented an independent prognostic factor.

It has to be kept in mind that part of the lymph nodes from the greater curvature (lymph node station 4sb, 4d, and 6) stay in situ in case of a gastric tube reconstruction after TAE with two-field lymphadenectomy, but nodal spread along the greater curvature does not seem frequent [43, 44]. Lymphatic drainage of the adenocarcinomas of the EGJ is described to the paracardial lymph nodes, lesser and greater curvatures, the D2-lymph node compartment, and the lower mediastinum; some authors even describe lymph node metastases in the middle/upper mediastinum and in the cervical region [8, 9, 40, 45,46,47]. This finding might be an explanation why an extended mediastinal lymphadenectomy might increase survival as it did in our study. The interpretation is, however, limited as the lymph node stations were not analyzed separately and the location of lymph node metastases was not recorded.

We could not detect significant differences in the number of resected lymph nodes, but the type of lymphadenectomy (extended mediastinal lymphadenectomy in case of TAE versus a lymphadenectomy only in the lower mediastinum in case of THG) may contribute to the difference in survival we found in our patients’ cohort. The better prognosis of our patients after TAE may also be the result of a lower recurrence rate, even if the differences were not statistically significant. Time to recurrence differed significantly after the two surgical procedures. A less aggressive tumor approach might lead to a higher risk of recurrence.

Regarding perioperative risk and complications, neither perioperative morbidity nor mortality differs in our patients’ collective; both types of resection seem feasible and safe.

Patients after TAE survived longer than patients after THG in our study. A difference in survival could also be observed in curatively treated patients (R0 resected patients without distant metastasis) as well as in patients younger than 70 years. Additionally, the type of surgery was an independent prognostic factor in our analysis. For patients with early gastric cancers (cT1/2 cN0) and for patients without neoadjuvant treatment, the type of surgery had no influence on survival. From that point of view our data suggest that the surgery of choice for locally advanced AEG II (>cT2 or cN+) might be a TAE given that they are in adequate general health to tolerate the thoracic approach.

To date, no randomized prospective trial has compared a TAE by right-sided thoracotomy with a THG. The only published prospective trial comparing a left thoracoabdominal approach to transhiatal approach was closed after interim analysis as patients with thoracoabdominal approach had no improvement of survival but a higher morbidity [48], confirmed in the 10-year follow-up [49]. A current systematic review and meta-analysis from our group could not settle this topic because available data were limited (under review); especially, data for patients with AEG II are missing.

One retrospective study comparing esophagectomy and gastrectomy in patients with AEG II did not show any differences in survival but a higher percentage of a positive circumferential resection margin after gastrectomy. The circumferential resection margin in esophagogastric carcinomas is not as well as studied as for rectal cancer, but results suggest that patients with a positive resection margin have a significantly reduced overall survival [50, 51] Positive lymph nodes in the upper mediastinum were found in 11% of the patients. The authors conclude that patients with AEG II should preferably be resected by esophagectomy as the two procedures did not differ in perioperative morbidity [40].

In contrast, Siewert suggests an abdominal approach with extended gastrectomy for patients with AEG II as in his study esophagectomy was associated with higher postoperative mortality without improving survival. However, only very few patients with AEG II were resected by transthoracic approach [8]. Another study compared patients initially classified as AEG I and resected by esophagectomy, who turned out to be AEG II in the histopathological report, to patients with AEG type II and resection by THG. Within this study the patients after gastrectomy survived longer [36]. A recently published study also compared thoracic and abdominal approaches for AEG II and III without differences in overall survival, R0 resection rate, and number of removed lymph nodes, but the authors demonstrated a survival benefit after an extended abdominal lymphadenectomy (D2) [52]. As mentioned earlier, the most important prognostic factors for esophageal and gastric cancer are a complete tumor resection, including the lymphatic drainage, as well as the presence of lymph node metastasis [7, 8]. The primary aim should be a complete tumor resection with free resection margins in all dimensions and an adequate lymphadenectomy. The decision which type of surgery should be performed can be guided by these principles.

Another important aspect regarding the question about the best surgical approach for patients with AEG II is the more and more frequently used minimally invasive approach. Further studies should include this aspect as perioperative morbidity, especially pulmonary complications, seem to be reduced and overall survival seems equal or might be even better after a minimal approach [53, 54].

To finally answer the question whether patients with AEG II tumors benefit from the thoracoabdominal approach, when complete tumor resection could also be achieved by abdominal approach, must be evaluated in a randomized controlled trial. Therefore, we are planning a multicenter trial including locally advanced AEG II after neoadjuvant treatment. The two treatment arms include a transhiatal extended gastrectomy and a thoracoabdominal esophagectomy with gastric tube reconstruction. With 3-year survival as primary endpoint and an estimated survival difference of 15%, a total of 260 patients must be analyzed to achieve a power of 80%. This number of patients seems realistic for a multicenter trial.

References

Blot WJ, Devesa SS, Kneller RW, Fraumeni JF Jr. Rising incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. JAMA. 1991;265(10):1287–9 (Epub 1991/03/23).

Falk J, Carstens H, Lundell L, Albertsson M. Incidence of carcinoma of the oesophagus and gastric cardia. Changes over time and geographical differences. Acta Oncol. 2007;46(8):1070–4. doi:10.1080/02841860701403046 (Epub 2007/09/14).

Siewert JR, Stein HJ. Classification of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction. Br J Surg. 1998;85(11):1457–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00940.x (Epub 1998/11/21).

Hasegawa S, Yoshikawa T. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: incidence, characteristics, and treatment strategies. Gastric Cancer. 2010;13(2):63–73.

Derakhshan MH, Malekzadeh R, Watabe H, Yazdanbod A, Fyfe V, Kazemi A, et al. Combination of gastric atrophy, reflux symptoms and histological subtype indicates two distinct aetiologies of gastric cardia cancer. Gut. 2008;57(3):298–305. doi:10.1136/gut.2007.137364 (Epub 2007/10/30).

Hansen S, Vollset SE, Derakhshan MH, Fyfe V, Melby KK, Aase S, et al. Two distinct aetiologies of cardia cancer; evidence from premorbid serological markers of gastric atrophy and Helicobacter pylori status. Gut. 2007;56(7):918–25. doi:10.1136/gut.2006.114504 (Epub 2007/02/24).

Hosokawa Y, Kinoshita T, Konishi M, Takahashi S, Gotohda N, Kato Y, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognostic factors of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction according to Siewert classification: experiences at a single institution in Japan. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(2):677–83. doi:10.1245/s10434-011-1983-x (Epub 2011/08/09).

Siewert JR, Feith M, Werner M, Stein HJ. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: results of surgical therapy based on anatomical/topographic classification in 1,002 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2000;232(3):353–60.

von Rahden BH, Stein HJ, Siewert JR. Surgical management of esophagogastric junction tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(41):6608–13 (Epub 2006/11/01).

Carboni F, Lorusso R, Santoro R, Lepiane P, Mancini P, Sperduti I, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: the role of abdominal-transhiatal resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(2):304–10. doi:10.1245/s10434-008-0247-x.

Fox MP, van Berkel V. Management of gastroesophageal junction tumors. Surg Clin N Am. 2012;92(5):1199–212. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2012.07.011.

Haverkamp L, Ruurda JP, van Leeuwen MS, Siersema PD, van Hillegersberg R. Systematic review of the surgical strategies of adenocarcinomas of the gastroesophageal junction. Surg Oncol (Oxf). 2014;23(4):222–8. doi:10.1016/j.suronc.2014.10.004.

Mullen JT, Kwak EL, Hong TS. What’s the best way to treat GE junction tumors? Approach like gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(12):3780–5. doi:10.1245/s10434-016-5426-6.

Rizk N. Gastroesophageal junction tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(12):3798–800. doi:10.1245/s10434-016-5427-5.

Giacopuzzi S, Bencivenga M, Weindelmayer J, Verlato G, de Manzoni G. Western strategy for EGJ carcinoma. Gastric Cancer. 2016;. doi:10.1007/s10120-016-0685-2.

Barbour AP, Lagergren P, Hughes R, Alderson D, Barham CP, Blazeby JM. Health-related quality of life among patients with adenocarcinoma of the gastro-oesophageal junction treated by gastrectomy or oesophagectomy. Br J Surg. 2008;95(1):80–4. doi:10.1002/bjs.5912.

Fuchs H, Holscher AH, Leers J, Bludau M, Brinkmann S, Schroder W, et al. Long-term quality of life after surgery for adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: extended gastrectomy or transthoracic esophagectomy? Gastric Cancer. 2016;19(1):312–7. doi:10.1007/s10120-015-0466-3.

Cunningham D, Allum W, Stenning S, Thompson J, Van de Velde C, Nicolson M, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(1):11–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055531.

Ychou M, Boige V, Pignon JP, Conroy T, Bouché O, Lebreton G, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(13):1715–21. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0597.

Sjoquist KM, Burmeister BH, Smithers BM, Zalcberg JR, Simes RJ, Barbour A, et al. Survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable oesophageal carcinoma: an updated meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(7):681–92. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70142-5.

Stahl M, Walz MK, Stuschke M, Lehmann N, Meyer HJ, Riera-Knorrenschild J, et al. Phase III comparison of preoperative chemotherapy compared with chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(6):851–6. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.17.0506.

van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, Steyerberg EW, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BP, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(22):2074–84. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1112088.

Klevebro F, Alexandersson von Dobeln G, Wang N, Johnsen G, Jacobsen AB, Friesland S, et al. A randomized clinical trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for cancer of the oesophagus or gastro-oesophageal junction. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(4):660–7. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdw010 (Epub 2016/01/20).

Ott K, Bader F, Lordick F, Feith M, Bartels H, Siewert J. Surgical factors influence the outcome after Ivor–Lewis esophagectomy with intrathoracic anastomosis for adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: a consecutive series of 240 patients at an experienced center. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(4):1017–25. doi:10.1245/s10434-009-0336-5.

Kirschner MB. Ein neues Verfahren der Oesophagoplastik. Arch Klin Chir. 1920;114:604–12.

Akiyama H, Hiyama M, Hashimoto C. Resection and reconstruction for carcinoma of the thoracic oesophagus. Br J Surg. 1976;63(3):206–9.

Hartwig W, Strobel O, Schneider L, Hackert T, Hesse C, Buchler MW, et al. Fundus rotation gastroplasty vs. Kirschner–Akiyama gastric tube in esophageal resection: comparison of perioperative and long-term results. World J Surg. 2008;32(8):1695–702. doi:10.1007/s00268-008-9648-z (Epub 2008/06/17).

Buchler MW, Baer HU, Seiler C, Schilling M. A technique for gastroplasty as a substitute for the esophagus: fundus rotation gastroplasty. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;182(3):241–5 (Epub 1996/03/01).

Moehler M, Baltin CT, Ebert M, Fischbach W, Gockel I, Grenacher L, et al. International comparison of the German evidence-based S3-guidelines on the diagnosis and multimodal treatment of early and locally advanced gastric cancer, including adenocarcinoma of the lower esophagus. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18(3):550–63. doi:10.1007/s10120-014-0403-x (Epub 2014/09/07).

Becker K, Langer R, Reim D, Novotny A, Meyer zum Buschenfelde C, Engel J, et al. Significance of histopathological tumor regression after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in gastric adenocarcinomas: a summary of 480 cases. Ann Surg. 2011;253(5):934–9. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e318216f449 (Epub 2011/04/15).

Becker K, Mueller JD, Schulmacher C, Ott K, Fink U, Busch R, et al. Histomorphology and grading of regression in gastric carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer (Phila). 2003;98(7):1521–30. doi:10.1002/cncr.11660.

Schmidt T, Sicic L, Blank S, Becker K, Weichert W, Bruckner T, et al. Prognostic value of histopathological regression in 850 neoadjuvantly treated oesophagogastric adenocarcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(7):1712–20. doi:10.1038/bjc.2014.94.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205–13.

Schmidt T, Alldinger I, Blank S, Klose J, Springfeld C, Dreikhausen L, et al. Surgery in oesophago-gastric cancer with metastatic disease: treatment, prognosis and preoperative patient selection. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(10):1340–7. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2015.05.005.

Barbour AP, Rizk NP, Gonen M, Tang L, Bains MS, Rusch VW, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction: influence of esophageal resection margin and operative approach on outcome. Ann Surg. 2007;246(1):1–8. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000255563.65157.d2.

Reeh M, Mina S, Bockhorn M, Kutup A, Nentwich MF, Marx A, et al. Staging and outcome depending on surgical treatment in adenocarcinomas of the oesophagogastric junction. Br J Surg. 2012;99(10):1406–14. doi:10.1002/bjs.8884 (Epub 2012/09/11).

Mariette C, Castel B, Toursel H, Fabre S, Balon JM, Triboulet JP. Surgical management of and long-term survival after adenocarcinoma of the cardia. Br J Surg. 2002;89(9):1156–63. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02185.x (Epub 2002/08/23).

Johansson J, Djerf P, Oberg S, Zilling T, von Holstein CS, Johnsson F, et al. Two different surgical approaches in the treatment of adenocarcinoma at the gastroesophageal junction. World J Surg. 2008;32(6):1013–20. doi:10.1007/s00268-008-9470-7 (Epub 2008/02/27).

Ito H, Clancy TE, Osteen RT, Swanson RS, Bueno R, Sugarbaker DJ, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia: what is the optimal surgical approach? J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199(6):880–6. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.08.015 (Epub 2004/11/24).

Parry K, Haverkamp L, Bruijnen RC, Siersema PD, Ruurda JP, van Hillegersberg R. Surgical treatment of adenocarcinomas of the gastro-esophageal junction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(2):597–603. doi:10.1245/s10434-014-4047-1.

Nienhueser H, Kunzmann R, Sisic L, Blank S, Strowitzk MJ, Bruckner T, et al. Surgery of gastric cancer and esophageal cancer: does age matter? J Surg Oncol. 2015;112(4):387–95. doi:10.1002/jso.24004 (Epub 2015/08/26).

Mariette C, Castel B, Balon JM, Van Seuningen I, Triboulet JP. Extent of oesophageal resection for adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29(7):588–93.

Pedrazzani C, de Manzoni G, Marrelli D, Giacopuzzi S, Corso G, Minicozzi AM, et al. Lymph node involvement in advanced gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134(2):378–85.

Ott K, Blank S, Ruspi L, Bauer M, Sisic L, Schmidt T. Prognostic impact of nodal status and therapeutic implications. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:15. doi:10.21037/tgh.2017.01.10.

Lerut T, Nafteux P, Moons J, Coosemans W, Decker G, De Leyn P, et al. Three-field lymphadenectomy for carcinoma of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction in 174 R-0 resections: impact on staging, disease-free survival, and outcome: a plea for adaptation of TNM classification in upper-half esophageal carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2004;240(6):962–74. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000145925.70409.d7.

Kakeji Y, Yamamoto M, Ito S, Sugiyama M, Egashira A, Saeki H, et al. Lymph node metastasis from cancer of the esophagogastric junction, and determination of the appropriate nodal dissection. Surg Today. 2012;42(4):351–8. doi:10.1007/s00595-011-0114-4.

Monig SP, Baldus SE, Zirbes TK, Collet PH, Schroder W, Schneider PM, et al. Topographical distribution of lymph node metastasis in adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49(44):419–22.

Sasako M, Sano T, Yamamoto S, Sairenji M, Arai K, Kinoshita T, et al. Left thoracoabdominal approach versus abdominal–transhiatal approach for gastric cancer of the cardia or subcardia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(8):644–51. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(06)70766-5.

Kurokawa Y, Sasako M, Sano T, Yoshikawa T, Iwasaki Y, Nashimoto A, et al. Ten-year follow-up results of a randomized clinical trial comparing left thoracoabdominal and abdominal transhiatal approaches to total gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction or gastric cardia. Br J Surg. 2015;102(4):341–8. doi:10.1002/bjs.9764 (Epub 2015/01/22).

Wu J, Chen QX, Teng LS, Krasna MJ. Prognostic significance of positive circumferential resection margin in esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97(2):446–53. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.10.043.

Chan DS, Reid TD, Howell I, Lewis WG. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the influence of circumferential resection margin involvement on survival in patients with operable oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 2013;100(4):456–64. doi:10.1002/bjs.9015.

Kneuertz PJ, Hofstetter WL, Chiang YJ, Das P, Blum M, Elimova E, et al. Long-term survival in patients with gastroesophageal junction cancer treated with preoperative therapy: do thoracic and abdominal approaches differ? Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(2):626–32. doi:10.1245/s10434-015-4898-0.

Tapias LF, Mathisen DJ, Wright CD, Wain JC, Gaissert HA, Muniappan A, et al. Outcomes with open and minimally invasive Ivor–Lewis esophagectomy after neoadjuvant therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(3):1097–103. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.09.062.

Palazzo F, Rosato EL, Chaudhary A, Evans NR 3rd, Sendecki JA, Keith S, et al. Minimally invasive esophagectomy provides significant survival advantage compared with open or hybrid esophagectomy for patients with cancers of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220(4):672–9. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.12.023.

Acknowledgements

G.M.H. reports fees for an advisory role from Sanofi, Roche, Taiho, Nordic, Lilly, Pfizer, a speaker’s honoraria from Roche, travel grants from Amgen, Ipsen, and Celgene; research funding is provided by Nordic and Taiho Pharmaceuticals. There is no relationship to the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human rights statement

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions.

Informed consent

Informed consent or substitute for it was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blank, S., Schmidt, T., Heger, P. et al. Surgical strategies in true adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction (AEG II): thoracoabdominal or abdominal approach?. Gastric Cancer 21, 303–314 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-017-0746-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-017-0746-1