Abstract

Background

A preoperative histologic diagnosis of neoplasia is a requirement for endoscopic resection (ER). However, discrepancies may occur between histologic diagnoses based on biopsy specimens versus ER specimens. The aim of this study was to assess the rate of discrepancy between histologic diagnoses from biopsy specimens and ER specimens.

Methods

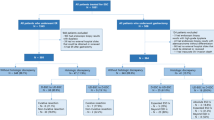

A total of 1705 gastric lesions, from 1419 patients with a biopsy diagnosis of neoplasia, were treated by ER from September 2002 to December 2008. We compared the histologic diagnosis from the biopsy sample and the final diagnosis from the ER specimen to assess the discrepancy rate. Clinicopathological characteristics of the lesions that were related to the histologic discrepancies were also studied.

Results

An ER diagnosis of gastric cancer was made in 49% (118/241) of lesions diagnosed as borderline lesions from biopsy specimens; this included adenomas and lesions difficult to diagnose as regenerative or neoplastic. The size, existence of a depressed area, and ulceration findings were significant factors observed in these lesions. An ER diagnosis of differentiated type cancer was obtained for 17% (12/63) of lesions diagnosed as undifferentiated type cancer from the biopsy specimens; for these lesions, the color and a mixed histology were significant factors related to the histologic discrepancies.

Conclusion

A biopsy diagnosis of borderline lesions or undifferentiated type cancer is more likely to disagree with the diagnosis from ER specimens. Endoscopic characteristics should be considered together with the biopsy diagnosis to determine the treatment strategy for these lesions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Endoscopic resection (ER) is an effective treatment for early-stage gastrointestinal neoplasms [1]. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) are popular ER techniques that are widely used for the treatment of early gastric cancer (EGC). In Japan, the EGC criteria for ER are based on technical limitations and the possibility of nodal metastasis. The criteria for EGC lesions indicated for ER proposed by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association include those with a preoperative diagnosis of differentiated type intramucosal cancer without ulcer findings, differentiated type intramucosal cancer that is no larger than 3 cm in diameter with ulcer findings, differentiated type minute invasive submucosal cancer (invasion less than 500 μm below the muscularis mucosa) that is no larger than 3 cm in diameter, and undifferentiated type intramucosal cancer that is no larger than 2 cm in diameter without ulcer findings [2]. Therefore, a preoperative histologic diagnosis based on biopsy samples is required before planning ER.

However, the diagnosis based on the biopsy samples sometimes does not correspond with the endoscopic diagnosis. Biopsy-based diagnoses are subject to the limitations of superficiality and sampling errors, sometimes leading to misjudgments in the treatment for the lesion. For EGC, a biopsy diagnosis of differentiated type adenocarcinoma is one of the requirements for ER. There are few studies examining the discrepancy between the histologic types of EGC diagnosed from biopsy samples versus the diagnosis from ER specimens. The aim of this study was to evaluate the discrepancy rate of diagnoses between biopsy samples and ER specimens, and to evaluate the clinicopathological characteristics of gastric lesions that were diagnosed differently with the two modalities.

Patients and methods

A total of 1705 gastric lesions from 1419 patients, who were treated by ER from September 2002 to December 2008 at a single prefectural cancer center, were included. The indications for ER at our institution include lesions with the findings of EGC that meet the Japanese EGC criteria for ER, diagnosed by endoscopy and chromoendoscopy, or a gastric neoplasia suspected of being EGC. For lesions suspicious for EGC endoscopically, a diagnostic ER was performed for lesions with a preoperative biopsy diagnosis of borderline lesion or neoplasia. As for elderly patients or EGC patients considered to be inoperable because of having an inadequate general condition for surgery, ER was selected for some EGC lesions that were diagnosed as an indication for surgery. In such patients, preoperative computed tomography was performed before the ER to confirm that distant metastasis was absent.

Clinicopathological data were retrieved from charts and endoscopic and pathology reports. Discrepancies between the histologic diagnoses based on biopsy specimens and those based on ER specimens were assessed (study 1). Three gastrointestinal pathologists at our hospital were involved in the histologic diagnosis in this study. Generally, the pathologists did not refer to the biopsy samples when they diagnosed the ER specimens. However, when a discrepancy occurred between the final diagnosis and the preoperative diagnosis, such as no tumor being found in the ER specimen or lesions changing in histologic type, there was a discussion between the pathologists with reference to the previous biopsy specimen. The histologic diagnosis of biopsy specimens was carried out according to the classification of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association [3, 4]. Biopsy histology is classified into five groups: normal or benign changes (hyperplasia/metaplasia) without atypia (group I); lesions with atypia resulting from regeneration (group II); borderline lesions including adenomas and lesions difficult to diagnose as regenerative or neoplastic (group III); lesions strongly suspected of carcinoma (group IV); and definite carcinomas irrespective of invasion (group V). For lesions with a biopsy diagnosis of definite carcinoma, the histologic type diagnosed by biopsy was compared to the final diagnosis obtained from ER specimens (study 2). All of the recognizable histologic types of cancer observed in the biopsy specimen (in one biopsy sample or 2 or more samples), were recorded. The diagnosis of mixed type histology was documented beginning from the histology of the major component; for example, well differentiated carcinoma > moderately differentiated carcinoma.

The ER methods used included EMR and ESD using an insulated-tip knife 1 or 2 (IT-knife 1, IT-knife 2). The details of ESD using the IT-knife 1 or 2 were described previously [5]. Written informed consent was collected from all patients undergoing endoscopy with biopsy sampling and before ER. This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board of our hospital (No. 22-J127-22-1-3). Statistical analysis was done using the χ2test, and a P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Clinicopathological data on the 1705 lesions are shown in Table 1. The method of ER was ESD in 99.5% (1697/1705) of the lesions. All lesions had a biopsy diagnosis of group III or more. The breakdown for groups III, IV, and V was 14, 6, and 80%, respectively. Among the 1360 lesions diagnosed as definite cancer (group V) from biopsy specimens, 1291 lesions were diagnosed as differentiated type cancer and 69 were diagnosed as undifferentiated type cancer.

Study 1: the discrepancy rate between histologic diagnoses based on biopsy specimens and those based on ER specimens

The discrepancies between the histologic diagnosis from biopsy specimens and the final diagnosis from ER specimens are shown in Table 2. Among 235 lesions with a biopsy diagnosis of group III (borderline lesions), 48% (112/235) were diagnosed as cancer. For lesions with biopsy diagnoses of group IV and group V, the final diagnosis was cancer in 93.6% (103/110) and 98.6% (1341/1360) of lesions, respectively. For lesions with upgraded histology, the final diagnosis of cancer was made by both cellular and structural atypia. In most cases, there were similar histologic findings in the ER specimen and biopsy sample. In nine lesions, no neoplastic change was found in the ER specimen. Seven of these lesions had a biopsy diagnosis of group V; six had a diameter smaller than 5 mm and one lesion was re-diagnosed as regenerative atypia based on the ER specimen.

Univariate analyses of clinicopathological factors associated with the final histology after ER in group III lesions are shown in Table 3. The factors shown in Table 3 were derived from endoscopic findings. Lesions with a diameter of 2 cm or more, the presence of a depressed area within the lesion, and the presence of ulcer findings within the lesion were significant factors related to lesions with a final diagnosis of cancer (P < 0.05).

Study 2: comparison of the biopsy diagnosis of histologic cancer type and the final diagnosis from ER specimens

The final diagnoses of 1360 lesions that had a biopsy diagnosis of definite cancer (group V) are shown in Table 4. For lesions with a biopsy diagnosis of differentiated type cancer, 97% (1253/1291) had a concordant final diagnosis of differentiated type cancer. For lesions with a biopsy diagnosis of undifferentiated type cancer, 17% (12/69) had a discrepant final diagnosis of differentiated type cancer; 8 of these lesions were diagnosed as mixed histology of differentiated and undifferentiated type cancer, and 4 lesions were diagnosed as pure differentiated type cancer without having the component of the biopsy histology.

Univariate analyses of clinicopathological factors associated with the final histologic type of cancer among lesions diagnosed as undifferentiated type adenocarcinoma by biopsy are shown in Table 5. The factors shown in Table 5, except for histologic type, were derived from endoscopic findings. The color of the lesion (normal to reddish) and the presence of mixed histology of differentiated and undifferentiated type within the lesion were significant factors related to discrepancies in the histologic type of cancer diagnosed from biopsy versus ER specimens.

A representative case of EGC with a discrepant diagnosis between biopsy and ER specimens is shown in Fig. 1a, b. The endoscopic diagnosis was a depressed type intramucosal cancer, 13 mm in diameter. The biopsy specimen showed poorly differentiated type cancer (Fig. 1c). Although undifferentiated type EGC is not an indicated lesion for ER, ESD was performed due to the patient’s advanced age and comorbidities; the ESD specimen is shown in Fig. 1d. The final diagnosis was an intramucosal cancer, 13 × 8 mm, moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, with no lymphovascular infiltration (Fig. 1e). Therefore, the treatment was considered to be a curative resection.

a A slightly depressed area (arrows), 13 mm in diameter, is observed in the gastric angle. b After chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine, an endoscopic diagnosis of a depressed type intramucosal cancer (arrows) was made. c The biopsy specimen showed poorly differentiated type cancer (H&E, ×10). d The specimen from the endoscopic submucosal dissection showed mucosal cancer in the red lined areas. e The final diagnosis was an intramucosal cancer, 13 mm in diameter, moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, with no lymphovascular infiltration (H&E, ×40)

Discussion

One of the advantages of ER is that a precise pathological evaluation can be obtained from the whole lesion resected in one piece. Forceps biopsy is sometimes inadequate for a correct histologic diagnosis and the foci of dysplasia may not be identified [6, 7]. In our present study, among 1705 lesions with a biopsy diagnosis of group III or more, nine cases (0.5%) had a final diagnosis of non-neoplastic tissue based on the ER specimen. Possible reasons for this discrepancy are that either the lesion was removed by biopsy or the biopsy diagnosis was an overestimation. The reasons why we conducted ER for the two lesions with a biopsy diagnosis of group III that were finally diagnosed as non-neoplastic were that the endoscopic finding of one of these lesions was a depressed type suspicious for EGC, and the biopsy of the other lesion showed high-grade gastric epithelial dysplasia.

The clinical management of gastric lesions with a biopsy diagnosis of borderline lesions, including adenomas and lesions difficult to diagnose as regenerative or neoplastic (so-called group III lesions), may differ among institutions. Repeat biopsy, follow-up, or ER may be options. Previous studies reported that 5.1–74% of group III lesions had a final diagnosis of cancer after ER [8–11]. In our present study, half of the group III lesions had a final diagnosis of cancer, and the rest were diagnosed as tubular adenomas. One of the reasons for the wide detection range of cancer from group III lesions is that the diagnosis for group III includes not only adenomas but also lesions difficult to diagnose as regenerative or neoplastic. In fact, group III includes lesions of categories 2 and 3 according to the revised Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia [12]. To address the need for a clinically meaningful classification, the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association recently published the 14th edition of the Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma (in Japanese) [13] and revised the group classification of gastric biopsy specimens, which is now closer to the Vienna classification.

For lesions diagnosed as adenomas from biopsy specimens and finally diagnosed as cancer from ER specimens, the endoscopic features indicative of cancer were a larger size, the presence of a depressed area within the lesion, and the presence of an ulcer or ulcer scar within the lesion. These endoscopic features have been reported previously [14–16], and the results of our study are compatible with these reports.

Considering the histologic type of cancer, the discrepancy rate for diagnosis was different between lesions diagnosed as differentiated type or undifferentiated type cancer. For lesions with a biopsy diagnosis of differentiated type cancer, 97% showed concordant histology, whereas only 83% of lesions with a biopsy diagnosis of undifferentiated type cancer had concordant histology. Analysis indicated that the presence of mixed histology with differentiated and undifferentiated types within the lesion was one of the features indicative of histologic type discrepancies, and these histologic type discrepancies might be due to the heterogeneity of gastric cancer. Also, biopsy specimens with tissue that was crushed due to technical problems would be inadequate to detect duct formation of the cancer cells, and a finding of no ductal formation would lead to the diagnosis of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma.

The limitation of the present study is that it was a retrospective analysis with data derived from a database of ER performed for gastric neoplasms. Therefore, some lesions with a biopsy diagnosis of group III may have been followed without ER depending on the patient’s background or the preference of the primary physician. However, as this study had a large sample size and high statistical power, we think the results of our study will be useful.

In conclusion, a biopsy diagnosis of borderline lesion or undifferentiated type cancer is more likely than other histologic diagnoses to show a discrepancy with the histologic diagnosis obtained from the ER specimen. Endoscopic characteristics should be considered together with the biopsy diagnosis to determine the treatment strategy for these lesions.

References

Kakushima N, Fujishiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastrointestinal neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2962–7.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Gastric cancer treatment guidelines. 3rd ed. Tokyo: Kanehara Shuppan; 2010.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma (in Japanese). 13th ed. Tokyo: Kanehara Shuppan; 1999.

Schlemper RJ, Kato Y, Stolte M. Review of histological classifications of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia: differences in diagnosis of early carcinomas between Japanese and Western pathologists. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:445–56.

Ono H, Hasuike N, Inui T, Takizawa K, Ikehara H, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Usefulness of a novel electrosurgical knife, the insulation-tipped diathermic knife-2, for endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2008;11:47–52.

Muehldorfer SM, Stolte M, Martus P, Hahn EG, Ell C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of forceps biopsy versus polypectomy for gastric polyps: a prospective multicentre study. Gut. 2002;50:465–70.

Szaloki T, Toth V, Nemeth I, Tiszlavicz L, Lonovics J, Czako L, et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection: not only therapeutic, but a diagnostic procedure for sessile gastric polyps. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:551–5.

Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T, Fukuda T, Kimura S, Uchida T, Obata A, et al. Diagnosis of borderline adenomas of the stomach by endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 1996;28:425–30.

Karita M, Tada M, Yanai H, Kawano H, Hirota K, Shigeeda M. Endoscopic and histological evaluation of group III lesions by strip biopsy. Gastroenterol Endosc. 1988;30:44–54. (in Japanese with an English abstract).

Muraki Y, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, Kakushima N, Tateishi A, Ogura K, et al. Treatment results of endoscopic submucosal dissection for group III lesions. J New Rem & Clin. 2006;55:72–4. (in Japanese).

Katsube T, Konno S, Hamaguchi K, Shimakawa T, Naritaka Y, Ogawa K, et al. The efficacy of endoscopic mucosal resection in the diagnosis and treatment of group III gastric lesion. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:3513–6.

Dixon MF. Gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia: Vienna revisited. Gut. 2002;51:130–1.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma (in Japanese). 14th ed. Tokyo: Kanehara Shuppan; 2010.

Kondo H, Saito D, Yamaguchi H, Shirao K, Watanabe Y, Ishido T, et al. Clinical follow-up and management of gastric benign/malignant borderline lesion. Stomach Intest. 1994;29:197–204 (in Japanese with an English abstract).

Kim YJ, Park JC, Kim JH, Shin SK, Lee SK, Lee YC, et al. Histologic diagnosis based on forceps biopsy is not adequate for determining endoscopic treatment of gastric adenomatous lesions. Endoscopy. 2010;42:620–6.

Jung MK, Jeon SW, Park SY, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO, et al. Endoscopic characteristics of gastric adenomas suggesting carcinomatous transformation. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2705–11.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma, 2nd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Takao, M., Kakushima, N., Takizawa, K. et al. Discrepancies in histologic diagnoses of early gastric cancer between biopsy and endoscopic mucosal resection specimens. Gastric Cancer 15, 91–96 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-011-0075-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-011-0075-8