Abstract

Collaborative research requires synergy among diverse partners, overall direction, and flexibility at multiple levels. There is a need to learn from practical experience in fostering cooperation towards research outcomes, coordinating geographically dispersed teams, and bridging distinct incentives and ways of working. This article reflects on the experience of the Collaborative Adaptation Research Initiative in Africa and Asia (CARIAA), a multi-consortium programme which sought to build resilience to regional climate change. Participants valued the consortium as a network that provided connections with distinct sources of expertise, as a means to gain experience and skills beyond the remit of their home organisation. Consortia were seen as an avenue for reaching scale both in terms of working across regions, as well as in terms of moving research into practice. CARIAA began with programme-level guidance on climate hotspots and collaboration, alongside consortium-level visions on research agenda and design. Consortia created and implemented work plans defining each organisation’s role and responsibilities and coordinated activities across numerous partners, dispersed locations, and diverse cultural settings. Nested committees provided coherence and autonomy at the programme, consortium, and activity-level. Each level had some discretion in how to deploy funding, creating multiple collaborative spaces that served to further interconnect participants. The experience of CARIAA affirms documented strategies for collaborative research, including project vision, partner compatibility, skilled managers, and multi-level planning. Collaborative research also needs an ability to revise membership and structures as needed in response to changing involvement of partners over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Collaborative research is becoming increasingly commonplace and seeks to apply a transdisciplinary approach to real-world issues. Together with funding for large consortia, this trend requires not only integrating across diverse theories and methods but managing across diverse organisations and geographies. This article looks at one multi-consortium research programme focused on regional environmental change and how it coordinated large teams, provided incentives for research collaboration, and managed itself adaptively. It provides an example of what collaborative research looks like in practice, combining insights on how to structure arrangements among participants and how to foster their interaction during the lifespan of a research programme based on multiple consortia.

More than one billion people live in river deltas, semi-arid lands, and glacier- and snowpack-dependent basins in Africa and Asia, regions where climate exposure and biophysical and social vulnerability coincide to create areas at high risk of climate change (De Souza et al. 2015). The Collaborative Adaptation Research Initiative in Africa and Asia (CARIAA, 2012–2019) was designed to support collaboration and learning within and between four transdisciplinary research consortia that sought to build resilience in these climate hotspotsFootnote 1.

A research consortium is a model of collaboration that brings together multiple individuals or organisations that are otherwise independent of one another, to address a common set of questions using a defined structure and governance model (Gonsalves 2014). Four consortia were formed in response to a call for proposals, identifying a lead or convening organisation, along with four other core partner organisations, which jointly convened or subcontracted a broader set of between four and 20 additional partners. Consortia constituted bounded intra-organisational networks, with membership delineated through formal contracting and specified tasks under joint work plans. Each consortium was managed by a principal investigator and coordinator hosted at the lead organisation, together with a set of co-principal investigators, one for each core partner organisation. All partners in a given consortium shared a common set of research objectives and a conceptual framework and identified high-level synthesis questions that transcended individual research projects. In addition, CARIAA was managed as a single programme including the four consortia and a variety of cross-consortia activities, with higher-order outcomes and common sets of synthesis questions toward which participants from all four consortia collaborated.

Over 5 years, CARIAA contributed to over 20 local or national adaptation plans and strategies and to over a dozen policies in 11 countries (Lafontaine et al. 2018). Outcomes included piloting adaptation technologies such as flood-resistant housing, informing the Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100, enhancing the capacity for vulnerability and risk assessment at the district level in Botswana, identifying investments to improve climate resilience in livestock value chains, and distinguishing the different impacts of + 1.5 °C and + 2 °C warming in hotspots.

The goal of CARIAA was to develop robust evidence on how to increase the resilience of vulnerable populations and their livelihoods in climate change hotspots. To this end, CARIAA sought to generate high-quality research; encourage its uptake through stakeholder engagement; and increase capacity to design, communicate, and use research and evidence. By mid-2019, CARIAA had produced 945 research outputs including 121 peer-reviewed journal articles and held 285 events reaching more than 9500 stakeholders, while 268 individuals benefited from capacity building such as graduate degrees, postdoctoral positions, and internships.

This article reflects on this programme in order to contribute to the literature on, and inform the practice of, collaborative research projects on regional environmental change. We share how the programme sought to coordinate and manage large teams, provide incentives for collaboration, and manage itself adaptively. We identify structural challenges such as power asymmetries within large-scale consortia and reflect on mechanisms to promote cooperation among partners in achieving research outcomes. While underpinned by empirical evidence, including surveys of consortia participants, as authors, we also critically reflect on our experience in managing CARIAA. All six authors served in the CARIAA programme management committee and contributed to several of the collaborative activities described below. Four of the authors served as coordinators in each of the research consortia, while the remaining two were based at the research funding agency that managed the programme. Collectively, we bring detailed knowledge of the inner workings of the consortia and programme, refined through reflective workshops during implementation, and tempered by writing this article more than a year after the programme closed (cf Gaziulusoy et al. 2016).

The next section summarises key insights from the existing literature on collaborative research, including a set of paradoxes facing managers. This is followed by a brief overview of the programme structure and our methodology. The experience of implementing CARIAA is described as approaches to supporting collaboration, namely, creating synergy among diverse partners, providing direction despite limited formal authority, and offering flexibility and funding at multiple levels. Situating CARIAA within the existing literature allows us to restate the paradoxes facing managers, the strategies used to confront them, and offer advice for adaptively managing future programmes. A concluding section restates our observations on coordination, incentives, and management within a multi-consortium programme.

Managing collaborative research

Collaborative and multi-scale research is necessary for effectively tackling regional challenges and producing evidence for policy responses at appropriate scales (Cochrane et al. 2017). There is recognition that transdisciplinary approaches are necessary to address wicked problems. Transdisciplinary teams seek to surpass the knowledge and ability of any single individual (Mauser et al. 2013). Such teams have several features, including a focus on praxis and the ability to navigate different perceptions or experiences of reality (Lotrecchiano and Misra 2018). Yet in practice the diverse nature of the teams required also brings significant challenges related to convening and managing research, which are not unique to climate change adaptation (e.g. Ayre et al. 2018; Gaziulusoy et al. 2016). Research project management in these contexts requires providing a sense of joint purpose, as well as breaking a larger purpose into smaller tasks and integrating these back together into a whole (König et al. 2013; Kenis and Raab 2020). vom Brocke and Lippe (2015) identify three paradoxes in collaborative research projects that have implications for how such projects are managed, and we unpack each of these below.

Their first paradox for research managers relates to the need to support the integration of diverse perceptions, values, and knowledge, yet the inclusion of diverse partners requires novel management structures and processes to deal with inter-cultural, inter-organisational, and inter-disciplinary differences. The potential barriers to collaboration that such management needs to overcome include differences in foundational training among team members, diverse and changing career paths, geographic dispersion, and limited ability for participants to grasp the breadth and complexity of the programme and its membership (Lang et al. 2012). Diverse partners and ambitious goals can also further exacerbate clashing perspectives on methodological standards, problem framing, and research design, including choices regarding units of analysis, ontology, and methods (Scholz and Steiner 2015; National Research Council 2015). Further barriers to collaboration that managers need to navigate include differences in working styles and differing institutional incentives and approaches to recognition (Boon et al. 2014; Varshney et al. 2016). If unmanaged, the transaction costs to individuals involved can discourage them from wanting to be part of an ambitious collaborative research agenda (Cummings et al. 2013).

Second, managers in large collaborative projects have limited authority over partners, who are autonomous and subject to their own organisational demands, yet the project vision and integrating results require commitment from all participants. Coordination is needed to commit diverse partners to a common purpose and hold themselves mutually accountable for performance (Cheruvelil et al. 2014), a task made harder by both the number of partners as well as their heterogeneity (often including both academic and non-academic partners). The existing literature has not given much attention to the perspectives of researchers and the basis on which they choose to collaborate, particularly within north-south arrangements that address multi-country partners and settings. Trust is foundational to decisions to collaborate (Cundill et al. 2019). Researchers frequently choose to collaborate with people they have worked with before (ESPA Directorate 2018). Managers play a key role in facilitating trust, by providing transparency in information and decision-making, as well as establishing norms of cooperation, including sanctions when they are not adhered to (Harris and Lyon 2013). A variety of factors associated with management styles affect the extent to which researchers commit to the larger goals of a collaborative research effort. Among these factors are the presence of effective leaders with an overall vision; respect for the needs, interests, and agendas of all partners; and an overall sense of justice and fairness in collaboration including clarity of roles, recognition in authorship, and benefits for communities involved in the research (Parker and Kingori 2016).

Third, research managers must offer flexibility given the multiple perspectives and complex issues at play and yet need tight management and firm structures to provide direction to diffuse teams and the pursuit of shared outcomes (vom Brocke and Lippe 2015). Collaborative management needs to create processes for group decision-making, handling conflict, and establishing procedures to assign credit and authorship over the works produced (Bozeman et al. 2015). This necessitates aligning incentives to bring together actors across scientific disciplines, knowledge domains, and policy and practice, although the mechanisms for achieving this are poorly understood. Managing collaborative research requires adaptive strategies as well as flexible funding to respond to the evolving and emergent nature of work (Gaziulusoy et al. 2016). Managers of projects and programmes need to invest intentional and ongoing effort to create and strengthen collaborative structures that balance flexibility (Pearce et al. 2009), which may include multi-level management committees to enable effective communication and identify where adaptive management may be required to meet the overall aim.

The literature has begun to identify how to organise large-scale programmes to foster for collaboration, learning, and synthesis (Harvey et al. 2017; Cochrane and Cundill 2018). Key issues that need to be addressed by managers, in addition to those described previously, include power asymmetries between partners, balancing different leadership styles, supporting the cooperation of parties with different aims and incentives, and, in large-scale collaborations in particular, addressing these issues through multi-layered features in design (Cundill et al. 2019; Lonsdale and Goldthorpe 2012; Jones et al. 2018). There is comparatively little evidence on how to put the emerging theory into practice on a day-to-day basis. This includes the role of managers in implementing these design features, fostering cooperation among diverse partners in achieving the research outcomes, effective approaches to coordinating geographically dispersed teams, and bridging distinct incentives and ways of working within collaborative research programmes. Given the literature, our contribution is to situate the experience of implementing CARIAA within the three paradoxes mentioned above to provide advice on managing collaborative research.

Structure and methodology

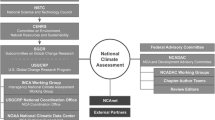

CARIAA’s formal structure centred on different committees for the overall programme and each research consortium. At the programme level, a management committee brought together the principal investigators and coordinators from the four consortia, to shape the agenda for learning reviews and decide on collaborative subprojects. These learning reviews were held each year from 2015 to 2018 and involved an in-person gathering of over a dozen participants from each of the four consortia. Such learning reviews served to share findings and celebrate achievements from each consortium, consolidate programme-level methods and tools—such as the theory of change and approach to research uptake—, and provide an open space for participants to share their work and explore opportunities to work across consortia.

At the consortium level, each convened a steering committee that brought together the co-principal investigators from the core partners to oversee budgeting, monitor research progress, and provide guidance on research uptake. Both the programme- and consortium-level committees met virtually once a month and in-person at least once per year. Each consortium created additional fora to coordinate among partners within a region or work on related activities, serving to further interconnect the overall programme through working groups, subprojects, and stakeholder engagement (see supplemental material).

This overall structure, and the extent to which it facilitated collaboration, serves as the focus of this article. The observations, quotes, and data described in the next section are based on responses to distinct surveys covering the 460 participants involved in the programme, as well as participant observation by the authors. Each consortium adopted a distinct approach to participant surveys. Within ASSAR, surveys were conducted at the midterm and end of the consortium (September 2016 and November 2018) which received 61 and 82 responses respectively. Questions focused on what respondents considered to be the most valuable and most challenging aspects of being part of that consortium. The surveys consisted of closed- and open-ended questions and were administered through Google Forms (Scodanibbio 2017). Survey responses were analysed inductively using thematic analysis, with codes developed iteratively. DECCMA conducted the same survey of its membership on a single occasion during the final year (February 2018) and collected 17 responses across a range of participants from co-investigators to early career researchers and practitioners. PRISE and HI-AWARE each used a different survey that emphasised monitoring or capacity building, and which gathered 18 and 62 responses, respectively. Further evidence comes from focus group discussions held with a broader set of CARIAA participants during programme-wide learning reviews in 2017 and 2018Footnote 2, as well as final technical reports produced for each research consortium (ASSAR 2019; DECCMA 2018; HI-AWARE 2018; PRISE 2019).

A limitation of our work is that each consortium adopted a distinct approach to implementing the participant surveys, which limits the ability to compile results across the programme. While we did not use formal social network analysis, CARIAA did have bounded membership and structures, providing an opportunity to learn from the consortia and programme as an experiment in inter-organisational networks (Burton and Obel 2018).

Approaches to supporting collaboration

Each consortium adopted a unique approach to organising its research activities and field sites (Table 1). DECCMA adopted the most uniform approach and methodology, working comparatively across two smaller deltas and one large transboundary delta. HI-AWARE involved twelve field sites across basins shared among the four contiguous countries in the Hindu Kush Himalaya mountains. ASSAR and PRISE were more geographically dispersed, using regional clusters or projects. Each consortium brought together the complementary strength of universities, think tanks, NGOs, and government agencies. The size, authority, and duration of the consortia were expected to contribute to research uptake and impact in building climate resilience. Consortia were “large” in terms of research activities and diverse geography, as well as the number of partners and their standing in the communities of research and practice. For example, collectively partners had ready access to villagers in remote locations as well as national officials in diverse countries. The sizable budgets and duration of the projects were expected to help build and sustain relationships with external actors over time.

Consortia included up to five core partners, convened in response to the research funding agencies’ original call for proposals, and sought out additional partners as needed to provide further reach or fulfil gaps within the work plan. This distinction created two tiers of participating organisations. Core partners enjoyed direct access to funding through grant agreements with the research funding agency and were formal members of consortium management. Meanwhile, additional partners were positioned as subcontractors, with more circumscribed set of responsibilities, and without a direct voice in consortium steering committees.

The structure of the programme did not permit the addition of new organisations as a core partner over the lifetime of a consortium. The expectation was that the core partners would remain locked in throughout the 5 years, yet two of the consortia lost a core partner early in the programme, with implications for reduced access to certain field sites and reorientation of responsibilities and budget. Another consortium experienced strained relationships among core partners over research design, which was eventually addressed through external facilitation and involvement of senior leadership from each organisation. The final consortium remained stable throughout the programme, aided by providing some autonomy to its regional nodes, each of which was led by a different core partner. These experiences suggest an opportunity to invest more time and effort in consolidating partnership, beyond refining research design and budgeting.

This section reflects on three aspects of implementing CARIAA inspired by the above-noted paradoxes in collaborative research projects. The first concerns efforts to realise synergy among diverse partners through efforts to address inter-cultural, inter-organisational, and inter-disciplinary differences. The second concerns efforts to provide direction and integrate contributions across diffuse teams to pursue shared outcomes, despite limited authority given that responsibility was distributed across partners. The third concerns the flexibility required for adaptive management through access to funding at multiple levels and fostering the creation of collaborative spaces when needed. Together, these aspects draw together the tasks of coordinating consortia to ensure agreement on research design and sustain arrangements among partners, the incentives that motivated partners—including forms of reward and recognition to harness diverse competencies—and managing through nested levels of shared leadership to guide consortia and respond to emergent opportunities.

Create synergy among diverse partners

Consortia sought to connect individuals and organisations that complemented each other. For example, ASSAR’s core partners brought complementary strengths on capacity building, on gender and social science, and on governance and climate science. Each consortium brought together diverse expertise and experience. Some participants had established track records authoring peer-reviewed publications and contributing to the scientific community, while others were graduate students. In particular, ASSAR participants appreciated “bringing in competencies that may not be the realm of researchers” such as skills in how to communicate to different audiences, think about how to influence policy, or lead change on the ground. Working with international experts across disciplinary boundaries was also widely appreciated as a benefit of working in consortia.

Each consortium operated across a unique set of countries and cultural settings. As recognised by one respondent, “all members of the consortium work in different ways (e.g. work culture, organisation structure)”. PRISE operated in West Africa and included both English and French within consortium management and quality review of publications. One participant noted the value of working “with a broad range of researchers and support staff with varied expertise and from different cultural backgrounds, all bringing with them strong knowledge basis and experiences that I have been able to learn from”. HI-AWARE noted that diversity among its partner organisations offered opportunities, yet cautioned that openness, intention, and patience were required for such diversity to be genuinely valued and understood.

Consortia needed to understand and respond to what motivated its partners. PRISE explicitly designed its work plan to provide activities and outputs that were recognised by each participant’s home organisation and aligned with their individual career paths. HI-AWARE probed partner motivations with respect to academic traditions, including differences in training and career paths among researchers from different countries. Some graduate students found that being involved in consortium activities distracted them from concentrating fully on their dissertation, even while providing exposure to new approaches. A similar tension arose between the academic demand to publish to advance one’s career and the administrative demand within the consortium to dedicate time to reporting, monitoring, and meetings. Nonetheless, many early career researchers reported high levels of satisfaction, mentioning the opportunities for mentorship outside of their home institutions, opportunities to contribute toward synthesis activities, and building social networks that were more global in scope. ASSAR found it important to ensure the inclusion of a sufficient number of senior researchers to ensure the quality of research produced and to mentor early career participants.

Given the extra burden required to collaborate with others, why did people and organisations choose to join a research consortium? In our surveys, participants revealed that they valued the ability to exchange perspectives and approaches across different geographical regions and engage with researchers across the world. More than 80% of DECCMA and ASSAR respondents rated their consortium as being beneficial to their work. ASSAR respondents connected their individual level of satisfaction with how the consortium provided professional growth, gains in skills and knowledge, and an ability to deliver on collective goals. Meanwhile, 93% of PRISE respondents agreed that building resilience in climate change hotspots required a scale of effort that exceeded what their organisations could achieve by working in isolation. Generalising from these responses, consortia were valued as a network that provided connections with distinct sources of expertise, the means to gain experience and skills, and avenues for working at a scale beyond the remit of their home organisations and countries.

In terms of creating synergy among diverse partners, the programme intentionally sought to foster participation by women and by individuals from the global south as authors. Nearly half (44%) of authors within CARIAA were women, which exceeds the level within IPCC reports, where women were 38% of authors in the special report on + 1.5 °C warming (SR15), and one-third of the authors named to the sixth assessment report. Most principal investigators were men, yet gender balance was stronger among the consortium coordinators (2 women and 2 men in most years) and among all participants (202 women out of 461 total participants). Ninety-six of peer-reviewed papers in CARIAA were co-authored, with 56% of these papers having co-authors based in different countries. Approximately 47% of all lead authors on these papers were based in the global south.

Consortia were seen as an avenue for working at scale, both in terms of geography as well as in terms of moving research into practice. In terms of geography, each consortium included organisations in the countries where it worked. These partners facilitated access to field sites and local communities, provided a grounded understanding of context, and enhanced the legitimacy and local ownership of the consortium’s activities, for example, navigating the regulatory requirements for conducting research. Extending across multiple countries, consortia were expected to connect research at multiple locations as well as compiling more comprehensive evidence across similar landscapes (O’Neill 2020). In terms of practice, each consortium was seen as an avenue for scaling science into local and national policy processes and implementing adaptation options on the ground. To engage potential audiences for research uptake, consortia included partners with skills in public communications, policy engagement, and community development. As one participant noted, consortia benefited by “choosing partners that already have well-established networks and higher-level government positions”.

Provide direction despite limited authority

Each consortium provided a common understanding of methods, research design, and each partner’s role in a variety of ways. Three of the consortia opted to permit some tailoring of methods and datasets between activities or regions. Early in the programme, the research funding agency required each consortium to prepare a work plan detailing the activities to be performed and deliverables to be created. In hindsight, this process jumped quickly to defining milestones and budgets and could have benefitted by ensuring clarity on direction, including partner expectations of the work and a common understanding of the ideas underpinning the research design. One respondent felt that “too much time [was] spent in conveying ideas and convincing scientists and partners having different subject backgrounds”, suggesting that there could have been more clarity and consensus. Early meetings benefit from a focus on trust-building between partners, agreeing to a joint vision and framing of what is desired, how work is to be undertaken, and how to deal with conflict and risk.

Participants across all four consortia struggled with competing demands on time. Over one-third of CARIAA participants reported that they faced different expectations within the consortium and their home institutions. One respondent cautioned that working in consortia “requires lots of time for relationship building, keeping everyone in the loop”. Surveys in the two semi-arid consortia pointed to the logistical challenges of working remotely and the time required for reporting. Respondents felt overwhelmed by multiple deadlines, demands, and information overload. As many activities involved multiple participants, any one member was often dependent upon others for needed inputs, giving rise to occasional bottlenecks and delays. Respondents noted moments when progress was constrained waiting for contributions from other partners. One participant recognised her/his role in the workflow, describing bottlenecks in “obtaining the necessary inputs from consortium members… and delivering results on time so other researchers in the consortium team could carry on with their assignments”. Email-based communication was insufficient for following up with colleagues, as participants could become less responsive over time, further compounding the frustration felt by colleagues over missed deadlines or unmet expectations.

Trust was challenged when a participant or organisation failed to fulfil their role. Within their home organisations, individuals could defer to the formal authority of senior personnel to intervene when issues arose. Yet consortia did not necessarily have such backstops if collaboration was not working. Participants mainly looked to principal investigators as a source of intellectual leadership, focusing research activities and ensuring rigour in the methods and publications. Principal investigators were supported by co-investigators from each of the core partner institutions. This form of leadership, however, meant that when problems were faced between partners, or when deadlines were not complied with, principal investigators lacked the teeth to enforce compliance. In the case of problems between partners, DECCMA relied on its monthly management committee and regular in-country meetings to rapidly identify and resolve issues arising. Within PRISE, in addition to monthly steering committee meetings, the consortium’s interlinked set of projects encouraged both more autonomous distribution of work and distinct links of mutual responsibilities among partner organisations. Collaboration across countries and organisations meant that partners relied on each other for delivery across the consortium, on the one hand creating a web of accountability yet adding to the complexity of arrangements.

Collectively, the consortium leaders shaped the experience of participants. In the words of one respondent, “leaders either inspire or de-motivate staff members, and either promote or hinder effective working environments. Their actions... have a direct bearing on the project's overall productivity and success”. Each consortium also had a coordinator who convened consortium-level committees, monitored and reported on research progress, and organised internal communication. Coordinators actively participated in cross-consortium arrangements for collaboration and knowledge sharing. These positions demanded a substantial time commitment, exceeding that allocated in consortium budgets or provided by their home organisations. They were also limited in the extent to which they could exercise formal leadership.

Periodic face-to-face meetings were crucial avenues where progress could be made in research outputs, decision-making and problem-solving between partners. These meetings were convened within each consortium, as well as across the programme as a whole. Each of these events involved dozens of participants, representing a sizable investment of time and budget. Yet such meetings were vital for coordination: creating a common understanding of progress and next steps, as well as increasing trust and deepening interpersonal relationships among participants. Such events helped supplement internal communications and virtual meetings, which were limited by uneven or unreliable access to the internet. One respondent noted that trust was “slow to develop due to the lack of time spent together. [Webconferencing] and emails take much longer to develop trust than handshakes and hugs”. Whereas partners could more readily follow up with phone calls or in-person with nearby colleagues, it was more difficult to elicit a response from partners located in faraway countries and time zones. Having met in person made it easier for participants to sustain their collaboration through online engagement. With time and experience, colleagues grew to appreciate each other’s expertise and empathise with each other’s needs, passions, and character. By the end of the programme, one participant noted that the consortium “had a genuine sense of family and community”.

Internal communications also helped to ensure transparency and foster a sense of belonging. A common knowledge management platform became an online location for participants across the programme to share files, convene web conferences, and coordinate schedules. Based on the Google Suite software, this platform provided a means to bridge the organisational firewalls that normally separated partners. It also provided access to working documents and manuscripts in preparation across the programme. Quarterly newsletters at the programme level and weekly digests at the consortium level kept participants informed about recent events and publications, as well as forthcoming meetings. Newsletters and digests also became a means to celebrate achievements and foster the identity of being part of the consortium, programme, or activity. Given the dispersed nature of a consortium, these efforts were vital in keeping partners engaged and motivated, particularly those participants who had fewer opportunities for face-to-face interactions.

A sign of successful coordination was that each individual cultivated their own unique role and contribution while feeling part of a greater whole. While at the start of the programme, participants identified only with their home organisations, over time they came to see themselves as part of a consortium contributing to a joint work plan. As each consortium matured, participants also identified with collaborative spaces within the broader programme. Thus, a participant could see herself as part of the Sustainable Development Policy Institute, as a partner organisation, part of PRISE as a consortium, and part of the cross-programme collaborative space on migration research.

Offer flexibility and funding at multiple levels

Given the number of partners and activities involved, it was initially daunting to manage a single research consortium, much less the overall programme comprising multiple consortia. Distributed leadership and nested committees provided coherence and autonomy at different levels, able to deploy adaptive funding to support emergent opportunities. Multiple collaborative spaces interconnected consortia through working groups, subprojects, and stakeholder engagement. Together, these nested levels of management created a pattern of relationships akin to a scale-free network. Each node or partner had detailed information from one level down, understanding a discrete set of activities and partners. Subsidiary levels also enjoyed some autonomy, while higher levels assembled the larger picture of consortium- and programme-wide progress. While the challenge of coordinating a consortium or programme can potentially rise precipitously with an increasing number of partners, each of the nested committees had a tractable span of control and membership. Each tended to involve 12 or fewer individuals, which proved conducive to reaching decisions and fostering trust.

Access to research funding was key. The consortium budget was divided into separate grant agreements, one for each of the core partners. This enabled funding to flow to multiple countries yet complicated the task of tracking financial progress across the consortium, as partners prepared separate reports on their spending. As consortium plans evolved and currency exchange rate fluctuated, significant time and diplomacy were required to renegotiate budgets and reallocate funding. Additional participants were dependent on core partners for access to funding. As one respondent cautioned, opportunities were sometimes skewed in favour of core partners. Compared with core members, additional participants were less involved in consortia management and had a narrower set of responsibilities.

Yet the use of adaptive funding provided a means for committees to respond to emergent opportunities for collaboration. Within consortia, PRISE provided funding opportunities for young researchers, while HI-AWARE tested a set of pilot technologies in communities. ASSAR provided small grants for working groups to develop cross-regional syntheses, respond to the needs of local communities, and follow through on ideas emerging from scenario planning processes. Having the option to tap into adaptive funding through different levels was vital for CARIAA’s geographically dispersed teams. One DECCMA participant noted the importance of “recognising that international collaboration cannot happen effectively without allocating a significant amount of resources (human, financial and time)”. Specific items mentioned included training, supporting delivery of research, data collection and data cleaning, analysis and peer review of findings, and authoring papers.

At the programme level, 9% of the overall budget was set aside for the broad purpose of “research integration”. The precise purpose and use of this budget were refined during programme implementation. The programme management committee decided how to allocate these funds, responding flexibly to new or unforeseen opportunities and fostering synergy among the four research consortia. In general, these funds created different collaborative spaces that convened participants from different consortia, either through ad hoc working groups or through successful bids to periodic calls for proposals open to the broader set of CARIAA participants. Specific efforts that were supported included stakeholder engagement platforms to reach national policy audiences in five countries where more than one consortium was present; communities of practice related to economics, research uptake, and systematic review; and collaborative subprojects that brought together consortia results on migration, gender, and adaptation pathways. This adaptive budgeting was also used to convene additional activity and research synthesis in response to the call for contributions to the IPCC special report on + 1.5 °C warming (Conway et al. 2019) and to compare changes in women’s agency associated with environmental stress across hotspots (Rao et al. 2019).

Such collaborative spaces served to interconnect the research consortia, creating further links in the network beyond the formal structure. This increased the connectivity among participants, providing multiple ties to the programme and encouraging additional outputs and syntheses of related activities. Yet it also generated additional workload and new demands on participants. In the final year, collaborative spaces were limited by time, as participants were already fully committed to delivering on their consortium activities. Invariably, certain partner organisations and individual participants became responsible for a variety of tasks. Large workloads and multiple responsibilities were particularly pronounced for the principal investigator and the lead organisation within each consortium. They tended to have a dual role both as a leader (tracking the consortium work plan, convening the steering committee, and participating in programme management) while also being responsible for their own distinct set of activities and deliverables.

Revisiting the paradoxes

Despite growing consideration of programme design for collaboration and learning, there is comparatively little evidence on how to put the emerging theory into practice. Based on our experience in implementing CARIAA, this includes practical steps to coordinate diverse partners in achieving the research outcomes, to create incentives for working together that also enable participants to advance within their home organisations, and to manage geographically dispersed teams by providing some degree of autonomy at multiple levels and adaptive access to funding. Our experience suggests options for restating the “paradoxes” of collaborative research projects (vom Brocke and Lippe 2015). CARIAA began with programme-level guidance on climate hotspots and collaboration, alongside consortium-level visions on research agenda and design. With these entry points, managers sought to realise synergy among diverse partners through initial and ongoing efforts to address inter-cultural, inter-organisational, and inter-disciplinary differences. Managers had to provide direction and integrate contributions across diffuse teams to pursue shared outcomes despite limited authority given that responsibility was distributed across partners. The flexibility required for adaptive management was facilitated by access to funding at multiple levels that allowed some opportunity for self-organisation and the creation of collaborative spaces when needed.

In implementing CARIAA, we unintentionally rediscovered the four general strategies for managing collaborative research projects identified by vom Brocke and Lippe (2015). First is to acknowledge the central role of project vision. While the daily minutiae of coordinating the programme and its consortia were daunting, the work was greatly aided by the overall focus on climate hotspots and a set of consistent research agendas. Second is to ensure partner compatibility and collaborative working style. Each research consortium intentionally sought out distinct partners that contributed to the project vision, both creating incentives to work together and responding to diverse interests among participants. Third is to allow for flexible, multi-level planning and monitoring. Intentional funding for emergent collaborative spaces as well as distinct structures at the programme, consortium, and project level afforded CARIAA opportunities for adaptive management.

Fourth is to appoint skilled project managers. Leadership at various levels was essential for fostering a common sense of purpose and identity. A leader is valued not only for her or his intellectual standing but for being genuinely interested in the relationships and tasks underpinning the collaboration (Parker and Kingori 2016). Within CARIAA, accountability ran upwards (from additional partners thru core partners to the research funding agency) and horizontally (networks across participants involved in collaborative spaces). Underpinning these was a mutual commitment to common purpose, at the consortium and programme level, predicated not on formal authority but leadership through motivation and soft skills. Principal investigators need to foster dialogue among participants and create mutual accountability, while coordinators cover diverse tasks ranging from internal communication and knowledge management to fulfilling administration processes to meet the requirements of the funding body (vom Brocke and Lippe 2015). Delegated and participative leadership needs to be collective and nurtured across a programme.

The networked structures of consortia and the programme were partially planned and partially emergent. The consortia were planned in their focus on climate change hotspots and the research funding agency’s requirement for an initial set of five core partners. Yet their structure also emerged as research activities and field sites were identified, and as consortia brought on additional partners and negotiated their respective roles. The programme anticipated the creation of collaborative spaces to bring different subsets of consortia participants together to work across hotspots and on common research interests. Yet the exact nature of these spaces emerged during the programme and changed as each refined their purpose and deliverables, responding to internal interest among participants and external opportunities for research uptake. The consortia and collaborative spaces formed for-purpose structures, or scaffolding, for participants to interact and perform together. By the final learning review, participants identified with the analogy of jazz improvisation, seeing themselves as musicians using the evolving structure of the consortia and programme as temporary stages upon which to unleash their creative and scientific energy, spontaneously jamming with colleagues in real time to produce novel melodies. The structure enabled participants to be attentive to each other’s work and find ways of making their own contribution to a collective work or performance.

Yet CARIAA was not without its challenges. The programme was perhaps over-engineered, with some redundancy and bottlenecks among different levels and collaborative spaces. Certain individuals became key in multiple nodes of the network, placing significant demands on their time and energy. For example, principal investigators convened the steering committee of their consortium, participated in collaborative management at the programme level, and had their own individual research responsibilities. Coordinators were similarly stretched across organising their consortium, participating in various programme-level working groups, and making their own individual contributions to work plans. Pleas to lighten reporting requirements and schedules were common in the final year of the programme, and the workload involved would not have been sustainable into the longer term. Moving forward, future programmes could lighten this workload, to distribute it among more people, or provide more support to critical individuals or nodes within the network.

Future programmes could also plan for consolidating a programme’s legacy. While the end of the CARIAA programme dissolved the consortia, participants sought to retain and reconfigure the relationships they wished to pursue further. This period also highlights a potential role for multi-consortium programmes in providing a legacy platform, to ensure outputs and data remain available into the future, as well as to nurture relationships among former partners and stakeholders. While it is tempting to simply move on to the next funding opportunity, there is value in maintaining a minimal structure following the programme to monitor ongoing research publications, synthesis, and stakeholder interest.

Future programmes could also include processes to facilitate the entry, exit, and changing involvement of partners over time. CARIAA could have better addressed the tension between core and additional partners and been more agile to accommodate changes in membership over the course of the programme. A multi-consortium programme should expect and enable revisions in its membership, including the ability to recognise increasing levels of involvement as initially peripheral partners or early career participants gain greater responsibility over time. In addition to incorporating new participants over time, it is useful to revisit the capacity of member organisations when there are changes in key personnel. There are limits to the ability to simply incorporate new partners, as those who joined CARIAA later found it difficult to understand the multiple activities, reporting requirements, and acronyms used by the existing participants. Staff recruitment and replacement became increasingly difficult over time, given the limited opportunity available to newcomers to shape the direction of the work and the need to use other people’s data.

A radical option would be to reconfigure the research consortia to address mounting issues related to size, complexity, and workload. Beyond the flexibility to more easily permit the entry and exit of partners, a programme could nurture collaborative subprojects as stand-alone entities. This would allow the consortia to scale down or reconfigure themselves to address their more unique activities and themes. For example, after CARIAA, cross-consortium work continued on topics such as how people adapt to exposure to heat stress in Asia, the implications of gender and social difference for adaptive capacity, and on the use of migration as an adaptation response. If the research consortia had continued, channelling such work into spinoff projects could have enabled the consortia to refocus on their research vision and on the topics on which they continued to have a more unique contribution, which in CARIAA included private sector adaptation, the barriers to adaptation, or broadening work within the same hotspots. Future research programmes need an ongoing ability to form, dissolve, and reform relationships, not only in creating and modifying collaborative spaces but extending to revisiting the initial formation of the research consortia.

Conclusion

This article describes the experience of the CARIAA programme which supported collaborative research examining regional environmental change across Africa and Asia. Evidence from surveys and focus group discussions with participants was used to make observations on the coordination of research consortia, incentives for collaborative research, and collaborative management at multiple levels. Each consortium assembled unique and complementary competencies of researchers, think tanks, non-governmental organisations, and government agencies. Each consortium tailored its own internal structure, field sites, and research activities. Participants appreciated investments made to establish and nurture teamwork yet faced competing demands on their time and experienced frustration when colleagues failed to deliver on their commitments in a timely fashion. Participants chose to join a consortium for the opportunity to conduct transdisciplinary research addressing the real-world challenge of climate change, to work across different geographical regions and with researchers across the world. Each consortium provided an avenue for scaling science into local and national policy processes and implementing adaptation options on the ground. Yet consortia needed to understand and respond to what motivates individuals and organisations, providing opportunities and recognition that contribute to participants’ diverse career paths and organisational interests. Nested committees provided coherence and autonomy at the programme, consortium, and activity level. Each level had some discretion to deploy funding and respond to emergent opportunities for collaboration. Multiple collaborative spaces enabled participants to work together on areas of common interest, increasing the number of connections within CARIAA as an inter-organisational network.

The experience of implementing CARIAA provides additional support for previous findings on managing collaborative research projects. Key among these are the need to ensure partner compatibility and collaborative working style and permitting flexible multi-level planning. Stepping beyond the established literature, the CARIAA experience offers insights on the design and implementation of future consortium-based research programmes: permit the networked structure within and among consortia to evolve as research activities and field sites are identified, as partners negotiate their respective roles, and collaborative spaces bring together different subsets of participants. Overcome barriers to collaboration by investing in structure, function, and leadership within and across research consortia. Recall that researchers choose to work with colleagues they trust, and with whom they devise practices and rules. Collaborative research is becoming increasingly commonplace and seeks to apply a transdisciplinary approach to real-world issues. At the same time, multi-consortium programmes require building partnerships to coordinate activities at a regional scale. Those that lead such large geographically dispersed teams need to utilise hard and soft systems to foster collaborative research that not only integrates across diverse theories and methods but connects diverse organisations.

Notes

Programme design was informed by reviews on the status of adaptation published in Regional Environmental Change special issue 15 (5).

Narrative summaries available http://hdl.handle.net/10625/56475 and http://hdl.handle.net/10625/55719

References

ASSAR (2019) Adaptation at scale in semi-arid regions (ASSAR): final report. http://hdl.handle.net/10625/58737. Accessed 24 Nov 2019

Ayre ML, Wallis PJ, Daniell KA (2018) Learning from collaborative research on sustainably managing fresh water. Ecol Soc 23. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09822-230106

Boon W, Chappin M, Perenboom J (2014) Balancing divergence and convergence in transdisciplinary research teams. Environ Sci Policy 40:57–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.04.005

Bozeman B, Gaughan M, Youtie J, Slade CP, Rimes H (2015) Research collaboration experiences, good and bad: dispatches from the front lines. Sci Public Policy 43:226–244. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scv035

Burton RM, Obel B (2018) The science of organizational design: fit between structure and coordination. J Org Design 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41469-018-0029-2

Cheruvelil K, Soranno P, Weathers K, Hanson P, Goring S et al (2014) Creating and maintaining high-performing collaborative research teams: the importance of diversity and interpersonal skills. Front Ecol Environ 12:31–38.https://doi.org/10.1890/130001

Cochrane L, Cundill G (2018) Enabling collaborative synthesis in multi-partner programmes. Dev Pract 28:922–931. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2018.1480706

Cochrane L, Cundill G, Ludi E, New M, Nicholls RJ et al (2017) A reflection on collaborative adaptation research in Africa and Asia. Reg Environ Chang 17:1553–1561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1140-6

Conway D, Nicholls RJ, Brown S, Tebboth M, Adger WN et al (2019) The need for bottom-up assessments of climate risks and adaptation in climate-sensitive regions. Nat Clim Chang 9:503–511. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0502-0

Cummings JN, Kiesler S, Zadeh R, Balakrishnan A (2013) Group heterogeneity increases the risks of large group size: a longitudinal study of productivity in research groups. Psychol Sci 24:880–890. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612463082

Cundill G, Harvey B, Tebboth M, Cochrane L, Currie-Alder B et al (2019) Large-scale transdisciplinary collaboration for adaptation research: challenges and insights. Global Chall 3. https://doi.org/10.1002/gch2.201700132

De Souza K, Kituyi E, Harvey B, Leone M, Kallur M, Ford JD (2015) Vulnerability to climate change in three hot spots in Africa and Asia: key issues for policy-relevant adaptation and resilience-building research. Reg Environ Chang 15:747–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0755-8

DECCMA (2018) Deltas, vulnerability, climate change, migration and adaptation: final technical report. http://hdl.handle.net/10625/57544. Accessed 24 Nov 2019

ESPA Directorate (2018) Ecosystem services for poverty alleviation programme highlights 2009-2018. Research into Results, Ltd, Edinburgh. http://www.espa.ac.uk. Accessed 23 Aug 2020

Gaziulusoy AI, Ryan C, McGrail S, Chandler P, Twomey P (2016) Identifying and addressing challenges faced by transdisciplinary research teams in climate change research. J Clean Prod 123:55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.08.049

Gonsalves A (2014) Lessons learned on consortium-based research in climate change and development. CARIAA working paper no. 1. http://hdl.handle.net/10625/52501. Accessed 16 Mar 2019

Harris F, Lyon F (2013) Transdisciplinary environmental research: building trust across professional cultures. Environ Sci Policy 31:109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2013.02.006

Harvey B, Pasanen T, Pollard A, Raybould J (2017) Fostering learning in large programmes and portfolios: emerging lessons from climate change and sustainable development. Sustainability 9:315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9020315

HI-AWARE (2018) Himalayan Adaptation, Water and Resilience (HI-AWARE): final technical report. http://hdl.handle.net/10625/57541. Accessed 24 Nov 2019

Jones L, Harvey B, Cochrane L, Cantin B, Conway D et al (2018) Designing the next generation of climate adaptation research for development. Reg Environ Chang 18:297–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1254-x

Kenis P, Raab J (2020) Back to the future: using organization design theory for effective organizational networks. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/govaa005

König B, Diehl K, Tscherning K, Heming K (2013) A framework for structuring interdisciplinary research management. Res Policy 42:261–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.repol.2012.05.006

Lafontaine A, Volonté C, Pionetti C, Moreno C, Gonzales M (2018) Collaborative Adaptation Research Initiative in Africa and Asia, summative evaluation final report. Le Groupe-conseil baastel ltée. http://hdl.handle.net/10625/57296. Accessed 12 Oct 2019

Lang DJ, Wiek A, Bergmann M, Stauffacher M, Martens P et al (2012) Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain Sci 7:25–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-011-0149-x

Lonsdale K, Goldthorpe M (2012). Collaborative research for a changing climate: learning from researchers and stakeholders in the ARCC programme. United Kingdom Climate Impacts Programme. https://ora.ox.ac.uk Accessed 24 Nov 2019

Lotrecchiano GR, Misra S (2018) Transdisciplinary knowledge producing teams: towards a complex systems perspective. Inform Sci J 21:51–74. https://doi.org/10.28945/4086

Mauser W, Klepper G, Rice M, Schmalzbauer BS, Hackmann H et al (2013) Transdisciplinary global change research: the co-creation of knowledge for sustainability. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 5:420–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.07.001

National Research Council (2015) Enhancing the effectiveness of team science. National Academic Press, Washington. https://doi.org/10.17226/19007

O’Neill M (2020) Collaborating for adaptation: findings and outcomes of a research initiative across Africa and Asia. IDRC: Ottawa, Canada. http://hdl.handle.net/10625/58971. Accessed 10 July 2020

Parker M, Kingori P (2016) Good and bad research collaborations: researchers’ views on science and ethics in global health research. PLoS One 11(10):e0163579. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163579

Pearce TD, Ford JD, Laidler GJ, Smit B, Duerden F et al (2009) Community collaboration and climate change research in the Canadian Arctic. Polar Res 28:10–27. https://doi.org/10.3402/polar.v28i1.6100

PRISE (2019) Pathways to resilience in semi-arid economies: consortium report. http://hdl.handle.net/10625/58343. Accessed 24 Nov 2019

Rao N, Mishra A, Prakash A, Singh C, Qaisrani A et al (2019) A qualitative comparative analysis of women’s agency and adaptive capacity in climate change hotspots in Asia and Africa. Nat Clim Chang 9:964–971. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0638-y

Scholz RW, Steiner G (2015) The real type and ideal type of transdisciplinary processes: part II - what constraints and obstacles do we meet in practice? Sustain Sci 10:653–671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-015-0327-3

Scodanibbio L (2017) What we learned from working collaboratively on the ASSAR project. ASSAR Learning Survey. http://www.assar.uct.ac.za/theme-learning. Accessed 1 Apr 2019

Varshney D, Atkins S, Das A, Diwan V (2016) Understanding collaboration in a multi-national research capacity-building partnership: a qualitative study. Health Res Policy Syst 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-016-0132-1

vom Brocke J, Lippe S (2015) Managing collaborative research projects: a synthesis of project management literature and directives for future research. Int J Proj Manag 33:1022–1039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.02.001

Acknowledgements

Marie-Eve Landry and Sarah Czunyi provided technical support for data curation and project administration.

Funding

This work was carried out with financial support from the Government of the United Kingdom - Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) and the International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Chandni Singh

The views expressed in this work are those of the creators and do not necessarily represent those of the UK Government, International Development Reseach Centre or its Board of Governors.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 168 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Currie-Alder, B., Cundill, G., Scodanibbio, L. et al. Managing collaborative research: insights from a multi-consortium programme on climate adaptation across Africa and South Asia. Reg Environ Change 20, 117 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01702-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01702-w