Abstract

There is pressing need to anticipate the impacts of climate change on species and their functional contributions to ecosystem processes. Our objective is to evaluate the potential bee response to climate change considering (1) response traits—body size, nest site, and sociality; (2) contributions to ecosystem services (effect trait)—crop pollination; and (3) bees’ size of current occurrence area. We analyzed 216 species occurring at the Carajás National Forest (Eastern Amazon, Pará, Brazil), using two different algorithms and geographically explicit data. We modeled the current occurrence area of bees and projected their range shift under future climate change scenarios through species distribution modeling. We then tested the relationship of potential loss of occurrence area with bee traits and current occurrence area. Our projections show that 95% of bee species will face a decline in their total occurrence area, and only 15 to 4% will find climatically suitable habitats in Carajás. The results indicate an overall reduction in suitable areas for all traits analyzed. Bees presenting medium and restricted geographic distributions, as well as vital crop pollinators, will experience significantly higher losses in occurrence area. The potentially remaining species will be the wide-range habitat generalists, and the decline in crop-pollinator species will probably pose negative impact on pollination service. The north of Pará presented the greatest future climatic suitability and can be considered for conservation purposes. These findings emphasize the detrimental effects on biodiversity and agricultural production by climate change and provide data to support conservation planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pollinating bees play a fundamental role in angiosperm reproduction (Ollerton 2017), in both natural and agricultural environments (Klein et al. 2007; Potts et al. 2016). They are essential to safeguard global food security due to their worldwide importance for crop production (Garibaldi et al. 2013; Potts et al. 2016). Besides, they actively contribute to the recovery of degraded ecosystems (Montoya et al. 2012; Williams and Lonsdorf 2018) and can also play a crucial role in sustainable development projects and programs (Wolff and Gomes 2015), by providing an extra source of income to traditional and low-income communities (Jaffé et al. 2015). Bee populations are in decline as a result of human activities, and the leading causes include changes in land use, competition with invasive species, pathogens, agrochemical usage, and climate change (Biesmeijer et al. 2006; Brown and Paxton 2009; Potts et al. 2010). This seems to be a general trend among insects since a recent review showed that global entomofauna is under severe threat of extinction, particularly those taxa belonging to Hymenoptera (Sánchez-Bayo and Wyckhuys 2019).

Anthropogenic climate change is a major menace for populations of both natural and managed species worldwide (Pacifici et al. 2017; Potts et al. 2016; Rafferty 2017), and the impacts of climate shift are already affecting species distributions, abundance, morphology, and phenology (MacLean and Beissinger 2017; Pacifici et al. 2015).

Climate is an important factor for pollinating bee species. Recent studies have shown that climate influences the community of pollinators (Devoto et al. 2009) and their behavior (Santos et al. 2015), potentially causing local extinction (Martins et al. 2015a, b). Potential reductions and shifts in the geographical distribution of crop pollinators were also projected due to climate change. One evaluation of bee pollinators projected losses of suitable occurrence areas for most of the evaluated species in Brazil (Giannini et al. 2012). Another study showed that passion fruit pollinators belonging to the genus Xylocopa could face reductions of up to 90% in their distribution areas in the Brazilian savanna (Giannini et al. 2013). A potential reduction of 8–18% in coffee-pollinating bees has been demonstrated for Latin America, affecting up to 30% of the future area of coffee production (Imbach et al. 2017). The tomato pollinators will likely face reductions in their areas of occurrence in Brazil, and Bombus morio Swederus 1787 will potentially face the largest reduction (up to 71% in the most pessimistic scenario) (Elias et al. 2017). Recent analysis considered the impact of climate change on the distribution of pollinators of 13 different agricultural crops in Brazil, showing that more than 90% of the municipalities that produce some of the analyzed crops will suffer loss of pollinators, and consequently some economical loss (Giannini et al. 2017).

Changes in rainfall and temperature regimes in response to greenhouse gas emissions may result, for example, in an average increase of 2 to 4 °C in global temperatures by 2050 (IPCC 2014). In the Amazon biome, climate change may alter the intensity (IPCC 2014), frequency (Marengo et al. 2009), and duration of extreme climatic events (Christensen et al. 2007). Results can include climate-induced shifts in species composition (Esquivel-Muelbert et al. 2018), and also ecological mismatches (Wood et al. 2018), which may compromise ecosystem functionality (Fei et al. 2017). Thus, understanding species responses to ongoing changes is imperative in order to maintain ecosystem functioning and sustainability.

One way to predict an organisms’ response to environmental changes (e.g., land use, competition, resource availability, and climate) is the use of species traits (response traits) (Schleuning et al. 2015). Species traits are any characteristic of an individual that can be assigned to a species, which could be phenological, morphological, physiological, reproductive, or behavioral (Kissling et al. 2018). Not only can species’ responses be measured and predicted by using trait-based approaches but also their contribution to ecosystem functions and services, and the potential impacts of non-random species loss on these processes (effect traits) (Bartomeus et al. 2018). For example, pollinators’ body size influences the response to land-use change (Steffan-Dewenter and Tscharntke 1999; Benjamin et al. 2014; Aguirre-Gutiérrez et al. 2016; Mayes et al. 2019), the compatibility with different floral morphologies (Armbruster and Muchhala 2009), and, also, the pollination efficiency per visit (i.e., pollen deposition) (Martins et al. 2015a, b).

Besides body size, other response traits can affect bee species when facing ecosystem pressures (De Palma et al. 2015). For example, nesting and foraging habits are strongly related to land use, with ground-nesting and polylectic bees being much less affected by agricultural or livestock expansion than cavity-nesting and oligolectic bees (Coutinho et al. 2018). Sociality is also an important response trait that could be affected by different ecosystem pressures, as social species are often food generalists and have long periods of activity (Michener 2007). On the other hand, crop-pollinator species (effect trait) are key providers of pollination services in agricultural landscapes and, thus, shifts in their distribution can directly impact food production and human well-being (Costanza et al. 1997; Garibaldi et al., 2013). Also, the size of geographical distribution is an important characteristic, since geographically constrained species are more sensitive to environmental changes, as they might be restricted to local environmental factors influencing their distribution patterns (Bommarco et al. 2010).

In this study, we present the first extensive list of bee species recorded in the Carajás National Forest, a protected area in the Eastern Amazon (southeastern region of Pará State, Brazil), where biological surveys and sampling efforts have been carried out since the 1980s. Together, this list comprises approximately 80% of the bees found in the Brazilian Eastern Amazon (Moure et al. 2008). The Carajás forest is within a mosaic of protected areas, surrounded by areas strongly impacted by land-use change, mainly due to the expansion of livestock and agriculture (Souza-Filho et al. 2016). In our study area, at least 21 of the crops produced depend on bees for their pollination (Supplementary Information A). We considered crop pollinators the bee species previously quoted on the literature as being effective pollinators of those crops (following Giannini et al. 2015a; Campbell et al. 2018). Bee species quoted as visitors were not included.

Here we evaluate the potential response of bees occurring in the Carajás National Forest (Eastern Amazon) to climate change considering (1) response traits—body size, nest site, and sociality; (2) contributions to ecosystem services (effect trait)—crop pollination; and (3) bees’ size of current occurrence area (Fig. 1). For this, we built a database of bee species and their traits and analyzed the impact of climate change on their distribution through species distribution modeling. To our knowledge, this is the first study to measure the potential future impact of climatic changes on bee species taking into account both their response and effect traits; moreover, it is also the first one to analyze the impact of climate changes on Amazon bees.

Material and methods

Study area

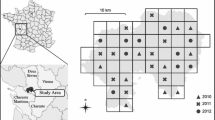

The study area is the Carajás National Forest, a protected area located in the southeast region of Pará State, Brazil (5° 52′ 11″ to 6° 32′ 13″ S latitude and 49° 53′ 28″ to 50° 44′ 29″ W longitude) (Fig. 2). The forest total size is approximately 400,000 ha, located within a mosaic composed of six national protected areas, encompassing a total range of almost 1,300,000 ha (Fig. 2). The Carajás Mosaic is an Amazonian domain, with altitudinal range of 400–900 m, and montane Amazonian climate with average annual temperatures of approximately 21 to 22 °C. The rainy season extends from November to April with an average precipitation/month of 229 mm, accounting for 79% of total annual rainfall (approximately 1800 mm) (ICMBIO 2016).

Study area. a Carajás National Forest in southeastern Pará state. b Aspect of the diversity of Carajás bees: (1) Xylocopa frontalis Olivier, 1789; (2) Melipona seminigra Friese; (3) Centris denudans Lepeletier, 1841; (4) Euglossa cognata Moure, 1970; (5) Euglossa imperialis Cockerell, 1922; and (6) Centris aenea Lepeletier, 1841 (photos: Fernanda Trancoso). c Photo of the region (by João Marcos Rosa)

Deforestation covers a great portion of the north and southeast of Pará, but in the western portion of the state, other protected areas can be found, relatively well-connected to large protected areas in the Western Amazon (Fig. 2). The high species richness found in preserved areas and the presence of considerable amount of degraded landscapes make the study site an area of particular importance for the understanding of the climate change impacts on pollinators.

List of bee species

The list of bee species reported for Carajás (Supplementary Information A) was determined from relevant scientific literature and public biodiversity data providers, such as speciesLink (a Brazilian repository of biodiversity data) and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). In addition, the final list was validated at the two Brazilian entomological collections that house the specimens collected in Carajás, pertaining to the Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi (MPEG) and the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG).

In this study, we chose to use the list of bees from the Carajás for two main reasons. Firstly, multi-taxa surveys have been conducted in Carajás since 1981, including a great variety of bees, whose data are available at the previously mentioned entomological collections. Secondly, basic biological information about the bee species listed for Carajás is still scarce; studies on traits or climate change impact were not previously made, which hinders decision-making processes.

The exotic bee species Apis mellifera L. occurs in our study region, as well as across almost the entire American continent. This widespread species is considered a habitat-generalist bee and occurs in almost all types of biomes and on degraded landscapes (Giannini et al. 2015b). For this reason, this species was not modeled through species distribution modeling (SDM) (see below).

Traits

Three of our traits are related to bees’ response to the environment (body size, nest site, sociality), and one is related to their functional contribution and provision of ecosystem services (crop pollination). These functional traits were used to categorize the bees and to evaluate if there is a tendency in the effects of climate change on some of these categories, aiming to subsidize conservation actions.

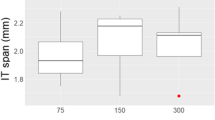

We measured the body size (based on intertegular distance (ITD)) of five specimens (available at previously mentioned entomological collections) for each of the species included in our study region that had been identified to the species level by a specialist taxonomist. We classified the bees into three body size classes (small, medium, and large) following other authors (Benjamin et al. 2014; Wray et al. 2014). We used the body size of bees in the genus Melipona Illiger, 1806 as the standard for medium size; they are the largest stingless bees, but are smaller than solitary carpenter bees (Xylocopa species). While small Meliponini bees are more likely to access very small flowers (e.g., açai flowers, see Campbell et al. 2018), Melipona size-like bees would access medium-size flowers (e.g., eggplant, see Nunes-Silva et al. 2003), whereas carpenter bees would access large-size flowers (e.g., passionfruit, see Junqueira and Augusto 2017). Thus, we considered bees with an ITD below that of the smallest Melipona species (< 2.2 mm) as small; bees with ITD ranging between the smallest and the biggest Melipona species (≥ 2.2 and ≤ 3.9) were considered medium; and those with ITD larger than the largest Melipona species (> 3.9) were considered large.

We retrieved information about nest site, sociality, and crop pollination from the relevant scientific literature (Supplementary Information A). Nest sites were classified into five categories: cavity, exposed (usually hanging from tree branches or anthropogenic constructions), soil, termite, or multi (when the species are reported to build their nest in more than one of the considered categories). Sociality affects pollination services mainly through the increase of foragers on flowers and is classified here in three categories: social, solitary, or cleptoparasitic. We did not consider intermediate stages of sociality, as it was not the focus in this work. Crop pollination information is represented as yes (crop-pollinator species) or no (not previously reported as a crop pollinator) (following Giannini et al. 2015a; Campbell et al. 2018). We considered crop species listed by IBGE as occurring in the municipalities around our study site, as well as bee species previously quoted as their pollinators on the study area (we did not include, at any stage, bee species quoted as visitors) (Supplementary Information A and E).

Finally, for the size of current occurrence area, we used the model generated by each species through SDM (see below). We categorize the area size as follows: (1) restricted ≤ 441,000 km2; (2) 441,000 < medium ≤ 882,000 km2; and (3) wide > 882,000 km2. We chose these values based on the sizes of occurrence areas presented by our bee species (Supplementary Information A and B). We followed this simple categorization since there is no other similar analysis in the scientific literature using such a high number of species with such a heterogeneous distribution. We also emphasize here that these values are based in the total known distribution of each bee species, which was used to produce the models in the SDM (see below); most of species presents broad distribution, and there is no endemic species in the study area.

Species distribution modeling

Occurrence records of each bee species were retrieved from the two abovementioned biodiversity data repositories (speciesLink and GBIF: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.8sujwg) and an internal database (named “bdbio”) totaling 11,952 records (Supplementary Information A and C), ranging from 2 to 347 occurrence points per species. Species occurrences were enough to produce good-quality models for the vast majority of species, which were supported by our modeling procedure that establishes a high threshold for model accuracy (TSS = 0.7, as explained below). A few species, however, presented low number of reported occurrences (< 10), which impeded modeling processes, and for this reason were not included in the present analysis (Table 1; Supplementary Information A).

For each species, we generated SDM models for the Neotropical region, as it represents the maximum complete distribution area of the bees in our dataset (Supplementary Information B), and, subsequently, models were projected only for Pará. This projection was chosen since our interest was to evaluate the future potential suitable areas outside of Carajás that could be suggested for the conservation of the analyzed bees and to evaluate the pollination service they provide in the same region. The dataset analyzed here is the best possible representative of each bee species distribution, since it compiles all updated available data; although there may be biases in the surveys conducted in the various regions encompassed by our analysis, SDM is considered a robust tool to be used in such a case (Peterson et al. 2011).

We used the biomod2 (Thuiller 2003) package for R (R Development Core Team) for SDM with two algorithms: maximum entropy (MAXENT; Phillips et al. 2006) and generalized linear model (GLM; McCullagh and Nelder 1989) algorithms. Both were chosen due to their frequent use and broad application (Li and Wang 2013). The environmental variables were chosen from the 20 least-correlated topo-bioclimatic layers (Aguirre-Gutiérrez et al. 2013) of the dataset available in WorldClim (Hijmans et al. 2005) that define the mean temperature and precipitation data for 1970–2000, as well as altitude. The following layers were used: altitude, isothermality, mean temperature of the driest quarter, annual precipitation, driest month, seasonality of precipitation, precipitation of the hottest quarter, and precipitation of the coldest quarter. We generated three sets of pseudo-absence data containing ten times the number of presence data randomly distributed (Chefaoui and Lobo 2008). The accuracy of the models was evaluated by true skill statistic (TSS) from three randomizations of 25% of the data, and the cutoff threshold of models was equal to 0.7, which produces highly accurate results and precludes model generation from poor data quality (Allouche et al. 2006).

The future scenarios were for the years 2050 and 2070, which were projected by the Hadley Center (HadGEM2-ES, Hadley Global Environment Model 2-Earth System) and the National Center for Atmospheric Research (CCSM4, The Complete Coupled System Model) and available on the WorldClim website with a 5-min arc resolution. Two greenhouse gas emission scenarios were used corresponding to representative concentration pathways (RCPs) equal to 4.5 and 8.5, which consider medium and high increases in emissions, respectively (IPCC 2014). Consensus models were built from calculating the averages of two scenarios (HadGEM2-ES and CCSM4) and the two algorithms (Maxent and GLM). To facilitate the interpretation and to standardize results, the final values of habitat suitability (i.e., the relative likelihood of occurrence) of a species were converted to percentages. The raster packages (Hijmans and Etten 2012) for R and the QGIS (Open Source Geospatial Foundation) were used for the spatial analysis.

Statistical analyses

The final models were used to calculate the occurrence range of the species in the current and future scenarios. We multiplied the cell area (10 × 10 = 100 km2) by the number of cells considered suitable by the model. Species richness was computed by stacking and summing the maps of all individual species for each scenario.

We quantified the proportional change in the size of occurrence area as the difference between the range in each future scenario and the current one (i.e., respFi = (area_futurei − area_current)/area_current; where i is a future scenario, see Supplementary Information A). We used the proportional change because species with wider range distribution may present higher loss rates simply because they have more area to lose than those more restrict species, and thus misleading the general trends of climate change effects. The betareg function in the betareg package (Cribari-Neto and Zeileis 2010) in R was used to model the potential loss of occurrence area in response to species traits. Predictor variables included all the traits and the size of current occurrence area (respFi ~ area.cat + size.cat + sociality + nest.location + crop.pollination, see Supplementary Information A). Beta regression shares properties with linear models, but is more applicable for modeling proportional data ranging from 0 to 1 (Ferrari and Cribari-Neto 2004). Only species with complete information on traits and those presenting future range losses were modeled (N = 151, Supplementary Information A). A transformation [(respFi × (number of observations − 1)) + 0.5)/number of observations] was applied to avoid zeros and ones (Smithson and Verkuilen 2006). The significant difference for each category was tested with post hoc Tukey tests as implemented in emmeans package for R.

Results

We obtained a total of 216 bee species recorded in the Carajás National Forest, which included representatives from the five bee families currently found in Brazil: Andrenidae (2 species), Apidae (189), Coletidae (2), Halictidae (15), and Megachilidae (8). Stingless bees accounted for 36% of bee species found in Carajás (77 species), whereas orchid bees accounted for 27% (59 species). Two genera of solitary bees alone correspond to 28% of the species (Euglossa Cockerell, 1917 with 39 species, and Centris Fabricius, 1804 with 23 species). We obtained the complete set of species traits for 167 of the species found in Carajás (Supplementary Information A). ITD ranged from 0.68 to 8.7 mm, with 65 species categorized as small, 38 medium, and 48 large body size. Solitary bees accounted for more than 50% of species (79 solitary species, 67 social, and 5 cleptoparasitic). Cavity-nesting bees totaled 81 species, 4 species build exposed nests, 38 nest in soil, 12 nest associated with termites, and 16 species use more than one nesting location. Of the analyzed species, 70 have been quoted as crop pollinators. As for bees’ occurrence area, 56 species were considered restricted, 54 presented medium occurrence areas, and 41 species presented wide occurrence areas.

Of the 216 total species, the impact of climate change could not be evaluated for 17 species (8%) (Table 1) due to the low number of occurrence points, making SDM unfeasible by the methodology used here (Supplementary Information A). The exotic bee species Apis mellifera L. was also not modeled, as already pointed. In addition, no current suitable habitats were projected for seven species. Of the total number of species analyzed by SDM (191 species), the vast majority (181 species, 95%) will potentially lose occurrence area; at least 135 (71%) will potentially lose more than 80% of occurrence area; and only between 29 (15%; 2050; RCP 4.5) and 7 (4%; 2070; RCP 8.5) will find suitable habitats specifically within Carajás in the future scenarios (Table 1; Supplementary Information A and D).

All beta regression analyses showed a good fit (pseudo-R2 ranging from 0.19 to 0.24, all P < 0.01; Table 2); however, only two of the analyzed characteristics showed significant differences related to the loss of suitable area in the future: size of current occurrence area and crop pollination (Fig. 3). In addition, these differences occur over short time periods (year 2050) and in the more optimistic scenario (RCP 4.5). Medium-to-restricted distributed species and crop pollinators will potentially be more negatively affected by short-term climatic changes occurring in the eastern portion of the Amazon basin (Fig. 3).

Estimated loss of area due to the impact of climate change for two significantly related traits of bees. a Crop pollination. b Size of current occurrence area. Models account for the year 2050 and 2070 and for two scenarios of carbon emission (RCPs 4.5 and 8.5). Different letters indicate significant differences (p values < 0.05) according to linear models

In general, the central and eastern portions of the Pará presented the highest species richness, according to our current projections (Fig. 4). Under future scenarios, a drastic potential reduction in the suitable habitats available for bee species has been detected. They will be restricted mainly to the northeast portion of the state, reaching a maximum of 80 (42%) species per grid cell (27 [24%] for species with restricted/medium distribution; or 18 [29%] for crop pollination species).

Discussion

Our models revealed that 95% of bees currently occurring on Carajás will face a decrease in occurrence area due to climate change impacts, and only 15 to 4% of the extant bee species will find climatically suitable habitats specifically in the Carajás region in the future. These results are particularly relevant since the diversity of bees in Carajás corresponds to 80% of species cited for the Eastern Amazon, as previously quoted, indicating that our study displays the general trends for bee distribution shifts in this area. Based on our models, species with restricted-to-medium occurrence areas and those that perform vital crop pollination services will suffer significantly higher losses in occurrence area, and the north portion of Pará will exhibit the most climatically suitable habitats for the analyzed bees.

The small number of bee species persisting in future scenarios on Carajás may have drastic consequences concerning interactions with the native flora. In our study, we reveal that the remnant bees (“winners”) will be wide-range habitat generalists, since bee species with restricted-to-medium occurrence areas will face significantly higher change on habitat suitability, which could imply on a wide trend towards biotic homogenization at the Carajás region in the future. Decreases in taxonomic, functional, and phylogenetic bee species richness due to homogenization (Harrison et al. 2018) will influence bee-plant interactions and plant distributions may also be strongly affected by pollinator range shifts (Rafferty 2017). Another concern regarding plants includes the fact that they are also susceptible to climatic variation pressures, and tree compositional shift followed by a more dry-affiliated flora has already been documented in the Amazon (Esquivel-Muelbert et al. 2018). However, the lack of up-to-date literature on wild bee-plant interactions both in the Amazon biome and in our study region poses an urgent need for studies on pollination syndromes (Rosas-Guerrero et al. 2014), on bee-plant interaction networks (Schleuning et al. 2015), and on provision of crop pollination services (Giannini et al. 2017).

Crop production is an important source of income in the municipalities surrounding Carajás, and the annual value of pollinator-dependent crops for these municipalities is estimated as being almost US$17 million in 2017 and the same in the 2018 (based on 14 crops listed in the IBGE website, Supplementary Information E) (data source: IBGE). Here we show that crop-pollinator bees will suffer a significantly higher loss of suitable occurrence area due to climate change. However, information on the interaction of local bees with those crops, their role in crop production, and the economic value of the pollination service provided by them is scarce. This lack of information highlights the need for basic knowledge and for developing conservation and crop management strategies (e.g., native species management) that consider sustainability of pollination services (Potts et al. 2016). Furthermore, data on animal pollinator dependence for regional crops is also scant (but see Giannini et al. 2015c), as well the annual production of crops not listed by the IBGE. Although we provide information on poorly known bee species distribution shifts here, the lack of complementary data makes it difficult to analyze an accurate impact of pollinator loss on regional agricultural production. Thus, the next steps for understanding the impact of bee losses in this area include to improve the knowledge about bee-plant interaction and local-crop production for which no information is available, mainly through field work.

Although our study provides evidence that some species will not find suitable habitats in the Carajás region, most of the species will find potential habitats in the northeast of Pará. To date, no other study has analyzed the impact of climate change on invertebrate species in this same area. However, other studies shown important suitable area reductions in the Amazon for vertebrates (Costa et al. 2018; Ribeiro et al. 2018; Miranda et al. 2019). All studies quoted showed a preponderance of future suitable habitats mainly in west and northeast of the state of Pará, which represents two important potential areas for conservation. Northeastern Pará is characterized by a higher annual volume of precipitation, when considering the state of Pará as a whole (Lopes et al. 2013), which is mainly associated with the intertropical convergence zone, a zone of maximum coverage of convective clouds interacting near the equatorial belt (Ferreira 1996). However, this area presents two distinct conditions in terms of land use. The westernmost portion corresponds to Marajó Island, a relatively well-preserved protected area, but habitats on the eastern portion corresponds to more degraded landscapes, inserted in the so-called arc of deforestation (Aldrich et al. 2012). This last area has the longest history of Amazon forest loss and retains only 24% of its original primary forest (Almeida and Vieira 2010). According to the IBGE, the municipalities of this area present low Human Development Index values (HDI—0.55 to 0.74) and the population reaches 1.4 million inhabitants in the capital alone. Particularly in this northeastern portion, restoration projects could be considered by stakeholders, mainly those projects that incorporate agroforestry production (IPCC 2007; Garibaldi et al. 2017), and also those that include native fauna management (e.g., beekeeping), which could help restoring ecosystem functions and services and also provide resources for low-income population in the region. Common bee species used in Pará State for beekeeping are mainly those pertaining to Meliponini tribe (stingless bees), such as, Melipona fasciculata, M. flavolineata, M. melanoventer, and M. seminigra. From these, our models suggest that only the first one (M. fasciculata) will find suitable habitats in Carajás. However, further studies could evaluate the effectiveness of other species for beekeeping.

The present study showed that the impact of climate change in Carajás would potentially severely reduce the number of bee species in the region, being significantly related to crop pollinators and species with more restricted distributional areas, with possible detrimental effects on biodiversity and agricultural production. Such impacts are of concern, especially in the absence of knowledge about species’ interactions, either with wild flora or with species of economic interest. Moreover, the Amazon biome is highly heterogeneous and will be impacted by climate change on different ways; thus, further studies addressing Western Amazon and/or other species are urgent. In this sense, the development of public policies that favor the creation and maintenance of research programs, and the protection and sustainable management of these species are important to guide conservation strategies supported by both public and private institutions.

References

Aguirre-Gutiérrez J, Carvalheiro LG, Polce C, van Loon EE, Raes N, Reemer M, Biesmeijer JC (2013) Fit-for-purpose: species distribution model performance depends on evaluation criteria-Dutch hoverflies as a case study. PLoS One 8(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0063708

Aguirre-Gutiérrez J, Kissling WD, Carvalheiro LG, Vries MFW, Franzén M, Biesmeijer JC (2016) Functional traits help to explain half-century long shifts in pollinator distributions. Sci Rep 6:24451. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24451

Aldrich S, Walker R, Simmons C, Caldas M, Perz S (2012) Contentious land change in the Amazon’s arc of deforestation. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 102:103–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2011.620501

Allouche O, Tsoar A, Kadmon R (2006) Assessing the accuracy of species distribution models: prevalence, kappa and the true skill statistic (TSS). J Appl Ecol 43:1223–1232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01214.x

Almeida AS, Vieira ICG (2010) Centro de endemismo Belém: status da vegetação remanescente e desafios para a conservação da biodiversidade e restauração ecológica. REU 36:95–111

Armbruster WS, Muchhala N (2009) Associations between floral specialization and species diversity: cause, effect, or correlation? Evol Ecol 23:159–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-008-9259-z

Bartomeus I, Cariveau DP, Harrison T, Winfree R (2018) On the inconsistency of pollinator species traits for predicting either response to land-use change or functional contribution. Oikos 127:306–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.04507

Benjamin FE, Reilly JR, Winfree R (2014) Pollinator body size mediates the scale at which land use drives crop pollination services. J Appl Ecol 51:440–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12198

Biesmeijer JC, Roberts SP, Reemer M, Ohlemüller R, Edwards M, Peeters T, Schaffers AP, Potts SG, Kleukers R, Thomas CD, Settele J, Kunin WE (2006) Parallel declines in pollinators and insect-pollinated plants in Britain and the Netherlands. Science 313:351–354. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127863

Bommarco R, Biesmeijer JC, Meyer B, Potts SG, Pöyry J, Roberts SPM, Steffan-Dewenter I, Ockinger E (2010) Dispersal capacity and diet breadth modify the response of wild bees to habitat loss. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 277:2075–2082. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.2221

Brown MJF, Paxton RJ (2009) The conservation of bees: a global perspective. Apidologie 40:410–416. https://doi.org/10.1051/apido/2009019

Campbell AJ, Carvalheiro LG, Maués MM, Jaffé R, Giannini TC, Freitas MAB, Coelho BWT, Menezes C (2018) Anthropogenic disturbance of tropical forests threatens pollination services to açaí palm in the Amazon river delta. J Appl Ecol 55:1725–1736. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13086

Chefaoui RM, Lobo JM (2008) Assessing the effects of pseudo-absences on predictive distribution model performance. Ecol Model 210:478–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2007.08.010

Christensen JH, Hewitson B, Busuioc A, Chen A, Gao X, Held I, Jones R, Kolli RK, Kwon WT, Laprise R, Magaña-Rueda V, Mearns L, Menéndez CG, Räisänen J, Rinke A, Sarr A, Whetton P (2007) Regional climate projections. In: Climate change 2007: the physical science basis. Chapter 11, contribution of working group I to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, USA

Costa WF, Ribeiro M, Saraiva AM, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL, Giannini TC (2018) Bat diversity in Carajás National Forest (Eastern Amazon) and potential impacts on ecosystem services under climate change. Biol Conserv 218:200–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.12.034

Costanza R, D’Arge R, de Groot R, Farber S, Grasso M, Hannon B, Limburg K, Naeem S, O’Neill RO, Paruelo J, Raskin RG, Sutton P, van den Belt M (1997) The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387:253–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/387253a0

Coutinho JGE, Garibaldi LA, Viana BF (2018) The influence of local and landscape scale on single response traits in bees: a meta-analysis. Agric Ecosyst Environ 256:61–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.12.025

Cribari-Neto F, Zeileis A (2010) Beta regression in R. J Stat Softw 1–24. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v069.i12

De Palma A, Kuhlmann M, Roberts SPM, Potts SG, Börger L, Hudson LN, Lysenko I, Newbold T, Purvis A (2015) Ecological traits affect the sensitivity of bees to land-use pressures in European agricultural landscapes. J Appl Ecol 52:1567–1577. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12524

Devoto M, Medan D, Roig-Alsina A, Montaldo NH (2009) Patterns of species turnover in plant-pollinator communities along a precipitation gradient in Patagonia (Argentina). Aust Ecol 34:848–857. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.2009.01987.x

Elias MAS, Borges FJA, Bergamini LL, Franceschinelli EV, Sujii ER (2017) Climate change threatens pollination services in tomato crops in Brazil. Agric Ecosyst Environ 239:257–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.01.026

Esquivel-Muelbert A, Baker TR, Dexter KG, Lewis SL, Brienen RJW, Feldpausch TR et al (2018) Compositional response of Amazon forests to climate change. Glob Chang Biol:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14413

Fei S, Desprez JM, Potter KM, Jo I, Knott JA, Oswalt CM (2017) Divergence of species responses to climate change. Sci Adv 3(5). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1603055

Ferrari SLP, Cribari-Neto F (2004) Beta regression for modelling rates and proportions. J Appl Stat 31:799–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/0266476042000214501

Ferreira NS (1996) Zona de Convergência intertropical. Boletim do Climanálise Especial. São Paulo. Available in: http://climanalise.cptec.inpe.br/~rclimanl/boletim/cliesp10a/zcit_1.html. Acess: 05/03/2018

Garibaldi LA, Steffan-Dewenter I, Winfree R, Aizen MA, Bommarco R, Cunningham SA, Kremen C, Carvalheiro LG, Harder LD, Afik O, Bartomeus I, Benjamin F, Boreux V, Cariveau D, Chacoff NP, Dudenhöffer JH, Freitas BM, Ghazoul J, Greenleaf S, Hipólito J, Holzschuh A, Howlett B, Isaacs R, Javorek SK, Kennedy CM, Krewenka KM, Krishnan S, Mandelik Y, Mayfield MM, Motzke I, Munyuli T, Nault BA, Otieno M, Petersen J, Pisanty G, Potts SG, Rader R, Ricketts TH, Rundlöf M, Seymour CL, Schüepp C, Szentgyörgyi H, Taki H, Tscharntke T, Vergara CH, Viana BF, Wanger TC, Westphal C, Williams N, Klein AM (2013) Wild pollinators enhance fruit set of crops regardless of honey bee abundance. Science 339:1608–1611. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1230200

Garibaldi LA, Gemmill-Herren B, D’Annolfo R, Graeub BE, Cunningham SA, Breeze TD (2017) Farming approaches for greater biodiversity, livelihoods, and food security. Trends Ecol Evol 32:68–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.10.001

Giannini TC, Acosta AL, Garófalo CA, Saraiva AM, Alves-dos-Santos I, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL (2012) Pollination services at risk: bee habitats will decrease owing to climate change in Brazil. Ecol Model 244:127–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2012.06.035

Giannini TC, Acosta AL, Silva CI, Oliveira PEAM, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL, Saraiva AM (2013) Identifying the areas to preserve passion fruit pollination service in Brazilian Tropical Savannas under climate change. Agric Ecosyst Environ 171:39–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.03.003

Giannini TC, Boff S, Cordeiro GD, Cartolano EA, Veiga AK, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL, Saraiva AM (2015a) Crop pollinators in Brazil: a review of reported interactions. Apidologie 46:209–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-014-0316-z

Giannini TC, Garibaldi LA, Acosta AL, Silva JS, Maia KP, Saraiva AM, Guimarães PR, Kleinert AMP (2015b) Native and non-native supergeneralist bee species have different effects on plant-bee networks. PLoS One 10:e0137198. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0137198

Giannini TC, Cordeiro GD, Freitas BM, Saraiva AM, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL (2015c) The dependence of crops for pollinators and the economic value of pollination in Brazil. J Econ Entomol 108:849–857. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/tov093

Giannini TC, Costa WF, Cordeiro GD, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL, Saraiva AM, Biesmeijer J, Garibaldi LA (2017) Projected climate change threatens pollinators and crop production in Brazil. PLoSONE 12(8):e0182274. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182274

Harrison T, Gibbs J, Winfree R (2018) Phylogenetic homogenization of bee communities across ecoregions. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 27:1457–1466. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12822

Hijmans RJ, Etten J (2012) Raster: geographic analysis and modeling with raster data. R Package Version 2.0–12

Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, Jones PG, Jarvis A (2005) Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol 25:1965–1978. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1276

ICMBIO (2016) Volume I: Diagnostico. In: Plano de Manejo da Floresta Nacional de Carajás. Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade, Brasilia, DF

Imbach P, Fung E, Hannah L, Navarro-Racines CE, Roubik DW, Ricketts TH, Harvey CA, Donatti CI, Laderach P, Locatelli B, Roehrdanz PR (2017) Coupling of pollination services and coffee suitability under climate change. PNAS 144:10438–10442. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1617940114

IPCC (2007) Climate change 2007: the physical science basis. In: Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M, Chen Z, Marquis M, Averyt KB, Tignor M, Miller HL (eds) Contribution of working group I to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, USA p 996

IPCC (2014) Climate change 2014: synthesis report. Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. (ed. R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer), pp.151, Geneva, CH

Jaffé R, Pope N, Carvalho AT, Maia UM, Blochtein B, Carvalho CAL, Carvalho-Zilse GA, Freitas BM, Menezes C, Ribeiro MF, Venturieri GC, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL (2015) Bees for development: Brazilian survey reveals how to optimize stingless beekeeping. PLoS One 10(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121157

Junqueira CN, Augusto SC (2017) Bigger and sweeter passion fruits: effect of pollinator enhancement on fruit production and quality. Apidologie 48:131–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-016-0458-2

Kissling WD, Ahumada JA, Bowser A, Fernandez M, Fernández N, García EA, Guralnick RP, Isaac NJB, Kelling S, Los W, McRae L, Mihoub JB, Obst M, Santamaria M, Skidmore AK, Williams KJ, Agosti D, Amariles D, Arvanitidis C, Bastin L, de Leo F, Egloff W, Elith J, Hobern D, Martin D, Pereira HM, Pesole G, Peterseil J, Saarenmaa H, Schigel D, Schmeller DS, Segata N, Turak E, Uhlir PF, Wee B, Hardisty AR, Hardisty AR (2018) Building essential biodiversity variables (EBVs) of species distribution and abundance at a global scale. Biol Rev 93:600–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12359

Klein AM, Vaissière BE, Cane JH, Steffan-Dewenter I, Cunningham SA, Kremen C, Tscharntke T (2007) Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc R Soc B: Biol Sci 274:303–313. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3721

Li X, Wang Y (2013) Applying various algorithms for species distribution modelling. Integr Zool 8:124–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/1749-4877.12000

Lopes MNG, De Souza EB, Ferreira DBS (2013) Climatologia regional da precipitação no estado do Pará. Rev Bras Climatol 12:84–102. https://doi.org/10.5380/abclima.v12i1.31402

MacLean SA, Beissinger SR (2017) Species’ traits as predictors of range shifts under contemporary climate change: a review and meta-analysis. Glob Chang Biol 23:4094–4105. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13736

Marengo JA, Jones R, Alves LM, Valverde MC (2009) Future change of temperature and precipitation extremes in South America as derived from the PRECIS regional climate modeling system. Int J Climatol 29:2241–2255. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1863

Martins KT, Gonzalez A, Lechowicz MJ (2015a) Pollination services are mediated by bee functional diversity and landscape context. Agric Ecosyst Environ 200:12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2014.10.018

Martins AC, Silva DP, Marco P Jr, Melo GAR (2015b) Species conservation under future climate change: the case of Bombus bellicosus, a potentially threatened South American bumblebee species. J Insect Conserv 19:33–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-014-9740-7

Mayes DM, Bhatta CP, Shi D, Brown JC, Smith DR (2019) Body size influences stingless bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) communities across a range of deforestation levels in Rondônia, Brazil. J Insect Sci 19. https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/iez032

McCullagh P, Nelder JA (1989) Generalized linear models. Chapman, Hall

Michener CD (2007) The bees of the world, 2nd edn. Johns Hopinks University Press, Baltimore

Miranda LS, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL, Giannini TC (2019) Climate change impact on ecosystem functions provided by birds in southeastern Amazonia. PLoS One 14(4):e0215229. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215229

Montoya D, Rogers L, Memmott J (2012) Emerging perspectives in the restoration of biodiversity-based ecosystem services. Trends Ecol Evol 27:666–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.07.004

Moure JS, Urban D, Melo GAR (2008) Catalogue of bees (Hymenoptera, Apoidea) in the Neotropical region. Available at http://www.moure.cria.org.br/catalogue. Accessed Dec/05/2018

Nunes-Silva P, Hrncir M, Silva CI, Roldão YS, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL (2003) Stingless bees, Melipona fasciculata, as efficient pollinators of eggplant (Solanum melongena) in greenhouses. Apidologie 44:537–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-013-0204-y

Ollerton J (2017) Pollinator diversity: distribution, ecological function, and conservation. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 48:353–376. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-022919

Pacifici M, Foden WB, Visconti P, Watson JEM, Butchart SHM, Kovacs KM et al (2015) Assessing species vulnerability to climate change. Nat Clim Chang 5:215–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2448

Pacifici M, Visconti P, Butchart SHM, Watson JEM, Cassola FM, Rondinini C (2017) Species’ traits influenced their response to recent climate change. Nat Clim Chang 7:205–208. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3223

Peterson AT, Soberón J, Pearson RG, Anderson RP, Martínez-Meyer E, Nakamura M, Araújo MB (2011) Ecological niches and geographic distributions. Princeton

Phillips SB, Aneja VP, Kang D, Arya SP (2006) Modelling and analysis of the atmospheric nitrogen deposition in North Carolina. Int J Glob Environ Issues 6:231–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.03.026

Potts SG, Biesmeijer JC, Kremen C, Neumann P, Schweiger O, Kunin WE (2010) Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol Evol 25:345–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007

Potts SG, Imperatriz-Fonseca V, Ngo HT, Aizen MA, Biesmeijer JC, Breeze TD, Dicks LV, Garibaldi LA, Hill R, Settele J, Vanbergen AJ (2016) Safeguarding pollinators and their values to human well-being. Nature 540:220–229. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20588

Rafferty NE (2017) Effects of global change on insect pollinators: multiple drivers lead to novel communities. Curr Opin Insect Sci 23:22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2017.06.009

Ribeiro BR, Sales LP, Loyola R (2018) Strategies for mammal conservation under climate change in the Amazon. Biodivers Conserv 27:1943–1959. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-018-1518-x

Rosas-Guerrero V, Aguilar R, Martén-Rodríguez S, Ashworth L, Lopezaraiza-Mikel M, Bastida JM, Quesada M (2014) A quantitative review of pollination syndromes: do floral traits predict effective pollinators? Ecol Lett 17:388–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12224

Sánchez-Bayo F, Wyckhuys KAG (2019) Worldwide decline of the entomofauna: a review of its drivers. Biol Conserv 232:8–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.01.020

Santos CF, Acosta AL, Nunes-Silva P, Saraiva AM, Blochtein B (2015) Climate warming may threaten reproductive diapause of a highly eusocial bee. Environ Entomol 44:1172–1181. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvv064

Schleuning M, Fründ J, García D (2015) Predicting ecosystem functions from biodiversity and mutualistic networks: an extension of trait-based concepts to plant-animal interactions. Ecography 38:380–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.00983

Smithson M, Verkuilen J (2006) A better lemon squeezer? Maximum-likelihood regression with beta-distributed dependent variables. Psychol Methods 11:54–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.11.1.54

Souza-Filho PWM, de Souza EB, Silva Júnior RO, Nascimento WR, Mendonça BRV, Guimarães JTF, Dall’Agnol R, Siqueira JO (2016) Four decades of land-cover, land-use and hydroclimatology changes in the Itacaiúnas River watershed, southeastern Amazon. J Environ Manag 167:175–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.11.039

Steffan-Dewenter I, Tscharntke T (1999) Effects of habitat isolation on pollinator communities and seed set. Oecologia 121:432–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420050949

Thuiller W (2003) BIOMOD-optimizing predictions of species distributions and projecting potential future shifts under global change. Glob Chang Biol 9:1353–1362. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00666.x

Williams NM, Lonsdorf EV (2018) Selecting cost-effective plant mixes to support pollinators. Biol Conserv 217:195–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.10.032

Wolff LF, Gomes JCC (2015) Beekeeping and agroecological systems for endogenous sustainable development. Agroecol Sustain Food Syst 39:416–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2014.991056

Wood TJ, Gibbs J, Rothwell N, Wilson JK, Gut L, Brokaw J, Isaacs R (2018) Limited phenological and dietary overlap between bee communities in spring flowering crops and herbaceous enhancements. Ecol Appl 28:1924–1934. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1789

Wray JC, Neame LA, Elle E (2014) Floral resources, body size, and surrounding landscape influence bee community assemblages in oak-savannah fragments. Ecol Entomol 39:83–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12070

Funding

We thank CNPq for grants (446167/2015-0; 443254/2015-0; 381626/2016-4; 380846/2017-9).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Orlando T. Silveira, Fernando A. Silveira, José E. Santos Júnior, Alessandro Lima, Beatriz W.T. Coelho, Kirstern L. F. Haseyama, Luciano Costa, Ulysses M. Madureira, Tiago Mahlman, Marcio Oliveira, Letícia Guimarães, and Alexandre Castilho for access on entomological collections and data, and for bee taxonomy. Alistair J. Campbell for suggestions on the manuscript. Andre L. Acosta, Rafael M. Brito, and Fernanda Trancoso for helping on maps and photos.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Wolfgang Cramer

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Giannini, T.C., Costa, W.F., Borges, R.C. et al. Climate change in the Eastern Amazon: crop-pollinator and occurrence-restricted bees are potentially more affected. Reg Environ Change 20, 9 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01611-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01611-y