Abstract

The effectiveness of various adaptation options is dependent on the capacity to plan, design and implement them. Understanding the determinants of adaptive capacity is, therefore, crucial for effective responses to climate change. This paper offers an assessment of adaptive capacity across a range of sectors in South East Queensland, Australia. The paper has four parts, including (1) an overview of adaptive capacity, in particular as a learning process; (2) a description of the various methods used to determine adaptive capacity; (3) a synthesis of the determinants of adaptive capacity; and (4) the identification of mechanisms to build adaptive capacity in the region. We conclude that the major issue impacting adaptive capacity is not the availability of physical resources but the dominant social, political and institutional culture of the region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change has become a central issue for governments, scientists and planners worldwide. Research and policy focus on climate change adaptation has emerged relatively recently as a fundamental challenge for contemporary socio-ecological systems. Importantly, this has compelled ‘a closer look at social relations and practices, even values, as sites for adaptation,’ in addition to technological measures (Pelling 2011, p. 6).

Australia is responding to the challenge of climate change through a range of both mitigation and adaptation initiatives—albeit with varying levels of success (Smith et al. 2011). In South East Queensland (SEQ), researchers have been working with key stakeholders to develop a set of adaptation strategies. The authors argue that it is not enough to present a set of strategies to stakeholders. There is a growing awareness that the formulation of adaptation strategies requires a deeper understanding of the human dimensions of climate change impacts (Adger 2003). To enable the formulation of successful adaptation strategies, it is important to assess the adaptive capacity of communities of place and practice (Lorenzoni et al. 2000; Ford et al. 2006) vis-à-vis any proposed adaptation strategy.

The paper is divided into four sections. The first provides an overview of how an investigation into adaptive capacity and adaptation options in SEQ was theorised; the second outlines the methods used to assess adaptive capacity and identifies determinants of adaptive capacity for the SEQ region; and the third offers a synthesis of these determinants and outlines recommendations to build adaptive capacity.

Theoretical context: understanding adaptive capacity

Adaptation responses are initiated by individuals or organisations and can be seen as efforts to manage system resilience, that is, to maintain, enhance or change socio-ecological system function and structure (Nelson 2011). Adaptive capacity is understood as a measure of the various components that determine how communities and sectors can respond to current and potential climate change impacts. As Katharine Vincent has noted:

Adaptive capacity is defined as a vector of resources and assets that represents the asset base from which adaptation actions and investments can be made (2007, p. 13).

The resources and assets of any community may be highly variable and include natural and financial resources along with institutional and cultural assets. Smit and Pilifosova (2001) identified adaptive capacity determinants within the general categories of economic resources, technology, information and skills, infrastructure and equity (Keskitalo et al. 2011). How such resources are deployed depends, as Adger (2006) has argued, on the perceptions of the agents acting within the system. Underlying such perceptions are different types of knowledge, values and goals shaped by institutional and cultural factors that establish the rational parameters that frame capacity and action within any given context. Negotiating such parameters extends beyond the individual and is in effect a social learning issue (Blackmore 2007). Social learning—‘learning from and with others’ (Thomsen 2008, p. 223)—comprises an important element of collective decision-making. Tàbara and Pahl-Wostl (2007) note that social learning is aided by: (1) ‘recognizing the diversity and complexity of the different mental models and cultural frames’ that stakeholders apply to defining problems and making decisions; (2) developing a collective mental model or shared view about the issue of concern; and (3) building trust through relationships among stakeholders to facilitate critical reflection.

Jakku and Lynam (2010) emphasise the process dimension of adaptive capacity and offer the following definition:

Adaptive capacity comprises the properties of a system that enable it to modify itself in order to maintain or achieve a desired state in the face of perceived or actual stress (p. 3).

Adaptive capacity is, therefore, a practical issue as it involves the ability to learn and adapt within a socio-ecological context (Berkes et al. 2003; Hinkel 2011). Linking learning to adaptive capacity allows it to be understood as a process that is both structural and cultural (Bussey et al. 2012). Thus, capacity is determined by both structural constraints such as environment, socioeconomics, infrastructure and demography and cultural factors such as values, norms, politics and the epistemic frameworks that shape the logic of decision-making. The interplay between stakeholders, the knowledge that frames acceptable decision-making and policy choices is complex and dynamic (Juntti et al. 2009). Thus, adaptive capacity is not simply about the physical capacity to implement adaptive responses. It is a negotiated process of social reasoning in which political, economic and subjective norms and values frame adaptive capacity (Lee 1993).

Determinants of adaptive capacity

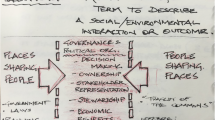

A fourfold approach was taken to assess the determinants of adaptive capacity in the SEQ region and to form the basis of the development of adaptive capacity improvement strategies (Smith et al. 2010). As adaptive capacity has both a structural and cultural dimension, the research design moved from the structural considerations that frame the socioeconomic context of the adaptive responses to climate change to a consideration of the cultural factors at play in adaptive decision-making. Thus, the first two stages of the approach focused on: (1) the dominant socioeconomic trends in SEQ (Roiko et al. 2012) and (2) a broad set of determinants framing adaptive capacity in a range of historical contexts (Bussey et al. 2012). The focus then moved to engagement with stakeholders across SEQ. Stakeholders working in climate change management and or policy development were drawn from local and state government agencies, NGOs and the private sector across the fields of urban planning, health, emergency management, coastal management and infrastructure (Table 1). The aim was to assess how they perceived the issue of climate change adaptation from: (3) a systems conceptualisation perspective and (4) a belief-about-the-system perspective (Richards et al. 2012). In the last stage, researchers worked with stakeholders to construct Bayesian belief networks (BBNs) to deepen understanding about adaptive capacity issues framing adaptation options (Richards et al. 2012). A conceptual model emerged that acknowledged the important relationships that exist across local, regional and global scales (Vincent 2007). The four lenses of socioeconomic trends, historical determinants, systems conceptualisations and BBNs offer both empirical and interpretive data to inform assessments of adaptive capacity (Fig. 1).

Conceptual model for assessing adaptive capacity (Smith et al. 2010)

The following sections describe the four research processes and summarise the findings from these four perspectives. The results represent an analysis of the SEQ decision-making context that frames the region’s current adaptive capacity vis-à-vis climate change. Such an overview is open to strategic and creative intervention, that is, social learning based in part upon the consideration of adaptation options suggested by the adaptive capacity assessment process described here.

Socioeconomic trends

Socioeconomic trends highlight the pressures that will increasingly frame the logic of decision-making over the coming decades. They also point to changes in social-economic context which need to be anticipated and planned for. A desktop analysis of current socioeconomic trends for SEQ based on Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 1996, 2001 and 2006 census data and projections on population and housing was undertaken (Stevenson 2002; Roiko et al. 2012). The study highlights the potential implications of the observed trends and projections for the sectors of: (1) Infrastructure, Human Settlements and Health; (2) Ecosystems and Biodiversity; (3) Energy; and (4) Agriculture. Dominant socioeconomic variables influencing sensitivity to climate change and adaptive capacity were also identified from the current climate adaptation literature. Subvariables related to population, household structure, housing, employment, income and education were then selected based on data availability (Roiko et al. 2012).

The SEQ population grew significantly (19 %) between 1996 and 2006. This trend is projected to continue with an increase of 56.7 % on the current estimated residential population of 2,827,566 by 2031. The SEQ region will also see a significant ageing of the population with upwards of 20 % of the population expected to be over 65 by 2031 compared to a current average of 13 %. Projections also show a doubling of lone person households and couples without children households and an increase of at least 60 % of one-parent family households across the region over the same time period. Population growth will not only increase the number of vulnerable people but also increase demand for land, as well as other goods and services including transport, energy, infrastructure and ecosystem services.

Of particular relevance to climate change adaptation, is the increasing concentration of infrastructure and population in the high-risk coastal urban areas (Wang et al. 2010) exposing more people and infrastructure to the impacts of sea level rise and more extreme weather events. The findings highlight the need to consider climate change adaptation under future likely scenarios for the region, rather than maintaining a business as usual approach towards the existing conditions. Such trends establish structural limits to climate change adaptation as they identify: (1) significant sections of the population who will be less able to adapt; (2) infrastructure vulnerabilities under current planning regimes; and (3) implications for ecosystems and agricultural systems due to increased population growth and urbanisation (e.g. Traill et al. 2011; Burley et al. 2012; Shoo et al. 2012). Of particular note is the increased vulnerability of disadvantaged groups in terms of their residential dwellings and their location. On the other hand, the early identification of such trends and inclusion in decision-making processes also point to important social learning opportunities for SEQ in terms of options to build resilience among communities.

Historical case studies

Thirty-three historical case studies were selected with reference to the key sectors of interest to the overall research project (human settlement and health, agriculture, ecosystems and biodiversity, and energy). The case studies were used to elicit a set of determinants that either positively or negatively frame the capacity to adapt (Bussey et al. 2012). Nine determinants of adaptive capacity were found: (1) complexity; (2) leadership; (3) institutions; (4) values; (5) technology; (6) imagination; (7) information; (8) knowledge; and (9) scale (Bussey et al. 2012).

The authors argue that central to defining any adaptive response is the degree of social complexity (Orr 2002, p. 40; Christian 2003, p. 457). Societies highly structured in terms of the number and variety of their components, social roles, and the mechanisms for organising these, are vulnerable to stress (Tainter 1998). They also tend to have a deep commitment to infrastructure that maintains their hierarchies and a resistance to forces that would challenge the dominant order (Diamond 2005; Bussey et al. 2012). Furthermore, these systems are highly energy dependent and reluctant to redeploy resources to enhance adaptive capacity (Quezada et al. 2012). In terms of leadership, an authoritarian style, which can be defined as ‘mobilising people toward a vision’ (Goleman 2000, p. 80), may work for a short period, but tends to inhibit the broad-based interaction necessary for social learning. Adaptive leadership, by contrast, facilitates multiple stakeholders’ priorities to define objectives and adaptive responses to change (Heifetz et al. 2009). It occurs through experimentation rather than decree and is required for reassessing values as well as mobilising people.

Institutions and the values that shape them were also important elements highlighted by the case studies. Values were not always inclined to support adaptive responses and in some instances worked against the best interests of the collective (Bussey et al. 2012). To challenge such values can appear to be risky to those working in the ‘coal face’ as it confronts habits and identity that are invested in current social and institutional practice. Risk involves moving from the ‘tried and true’ into the unknown (Beck 2009).

Technology and imagination were intimately linked in the historical record. The impact of technologies on human experience has been profound as it shaped the physical contexts in which humans lived and worked, our ways of understanding the world, social identity and social choices (Landes 2007; Ponting 2007; Halal 2008). Similarly, societies in the past with high imaginative capacity have been able to more effectively break unsustainable path dependencies and transform their societies to build resilience (Diamond 2005; Wright 2006). In addition, information and knowledge were also important in challenging dominant value structures (Bates 2005; Ferguson 2010). They informed adaptive leadership and the attention to context necessary for timely responses to environmental and social change (Heifetz et al. 2009; Ravetz 2011).

Finally, the larger and more complex a system, the easier it was to hide dysfunction for longer. Thus, as already noted, scale is a central issue in any assessment of adaptive capacity (Yohe and Tol 2002; Adger et al. 2005; Vincent 2007).

The historical determinants point to macro-level processes at work in other human systems. Just as the socioeconomic trends suggest a set of climate change scenarios for SEQ, the historical case studies suggest historical scenarios relating to adaptive capacity in SEQ (Bussey et al. 2012). These historical scenarios were of four kinds: (1) continuity in which growth remains the dominant theme of social progress; (2) collapse in which leadership and institutional failure, lack of vision, and an inability to assess risks and act on clear knowledge, combine with a declining resource/energy base to lead to system failure; (3) containment in which society scales back to match resource availability and in which balance is maintained by recourse to authoritarian governance structures or some kind of utopian vision (or both); and (4) transformation in which the adaptive capacity of a group is equal to the challenge faced and a new form of civilisational programme emerges.

Systems conceptualisation

A systems conceptualisation process was developed that combined a community-based and participatory approach with systems thinking to shift the focus from macro-determinants and trends affecting adaptive capacity to context-specific issues that stakeholders identified as being relevant to an assessment of adaptive capacity and climate change. The approach explored how climate change, in combination with other drivers, can affect different locations and sectors of the SEQ region. This approach built on earlier research on adaptive capacity in the Sydney region (see, for example, Smith et al. 2007; Preston et al. 2009; Smith et al. 2009; Measham et al. 2011). Six participatory workshops were held with 66 stakeholders representing a range of relevant decision-making responsibilities within government agencies, NGOs and the private sector. Four systems conceptualisation workshops corresponded with four coastal and peri-urban settlement types representative of the region (refer to Table 1). These were matched with seven sectors (urban planning, health, emergency management, infrastructure management, coastal management, environmental conservation and energy), with representatives from each attending the workshops. Two additional workshops addressed separate sectoral interests: (1) marine biodiversity and coastal wetlands, focusing on the Moreton Bay Marine Park; and (2) future energy supply, with one of the major regional energy companies, Energex (Table 1).

The workshops enabled researchers and stakeholders to develop a collective system conceptualisation, or shared understanding of the climate change pressures, impacts and responses affecting their respective sectors (Richards et al. 2012). Through this approach, both direct and indirect drivers of change and climate change impacts were identified and stakeholders were able to prioritise possible adaptation responses for the region. Stakeholders identified 22 priority issues as indicators of adaptive capacity.

A dominant theme in all workshops related to the implications of government policy and leadership on adaptive capacity. More specifically, much discussion focused on the impact of policy on social cohesion. Funding was also a recurrent theme as adaptive capacity was consistently linked with the availability of finance for any possible adaptation strategy. The nature of leadership (consistent, ambivalent or inconsistent) was seen as underpinning success or otherwise of adaptation strategies.

Two further recurring themes were identified by stakeholders. The first was the importance of social values in shaping the decision-making context. Participants regularly linked values with the success or otherwise of adaptation strategies involving biodiversity, health and social justice issues. The second theme was innovation, with particular reference to planning where there was a perceived need to take risks, challenge norms and create new platforms for sustainable communities into the future. Innovation was also cited in relation to policy development, funding and capturing the social imagination in order to shift thinking and norms that were counter-productive to adaptive capacity and social learning (Sano et al. 2012).

Through the systems conceptualisation processes, stakeholders were able to interrogate systems linkages (i.e. direct and indirect causal linkages and feedback loops) in order to prioritise climate change issues. This interactive group enquiry enabled the development of a model of climate change drivers, impacts and responses for the region and provided a basis for the BBN analysis which followed.

Bayesian belief networks

The development of Bayesian belief networks (BBNs) continued the process of systems conceptualisation described above by eliciting the workshop participants’ opinions of the likely outcomes of various system states (Richards et al. 2012). BBN modelling (Charniak 1991) is a useful methodology for representing the causal relationships of a system in circumstances of variability, uncertainty and subjectivity. BBNs allow for data from different sources and of different accuracies to be combined in a single framework (Uusitalo 2007). They also have the capacity to deepen the understanding of the affective domain that frames decision-making and the logic behind this. Thus, they complement the systems conceptualisation work which maps the issues inherent to a socio-ecological system by addressing causality (probabilistically) with estimated likelihoods and consequences of nested determinants (Richards et al. 2012).

During the workshops, stakeholders worked within sectoral groupings of at least three participants. Each group identified a priority issue relating to climate change and adaptive capacity within their sector, and was guided by the researchers in the development of a BBN structure around their respective priority issues. For example, participants were instructed to identify primary variables that directly influence their capacity to manage their group’s priority issues, and in turn, to identify the variables that directly influence the primary variables. The process followed for developing causal, hierarchical layers in the BBN structures, for assigning conditional probabilities to each causal relationship and to capturing narrative insights into participants’ understanding of relationships between variables, is described in detail in Richards et al. (2012).

As part of the process to develop BBN models, stakeholder participants were required to assign two states to their priority issues (without defining them further), reflecting the subjective nature of BBNs. For example, two emergency management sector groups determined that ‘resilience’ was a priority issue. While one group identified the desirable state of ‘self-recovery’ and the undesirable state of ‘aided-recovery’, the other group identified states of ‘high’ and ‘low’ resilience (Richards et al. 2012, p. 4). Further examination using BBN modelling identified 245 variables influencing the priority issues, that is, perceived determinants of adaptive capacity (Richards et al. 2012). Further network analysis of these variables identified recurrent themes or generic determinants, such as the level of funding available and the nature of policy responses required (Richards et al. 2012). Through an iterative cycle, the BBNs identified the following: (1) community well-being/resilience/support; (2) adequate funding; and (3) and proactive policies, as central determinants in shaping the adaptive capacity context. However, as observed by Richards et al. (2012), the influence of generic determinants was moderated by sector-specific determinants, confirmed in post-workshop interviews with stakeholders.

Synthesis of determinants and application to stakeholder strategies

Our aim was to identify factors impacting on success or failure of adaptation options in the SEQ region. It is argued that understanding these capacity issues empowers stakeholders to more effectively design, plan and implement regional adaptation strategies for SEQ.

Table 2 summarises the determinants identified through desktop analysis, historical research and stakeholder engagement. Each set of determinants represents a different group of processes at work in the structural and cultural context of the SEQ stakeholders. Together they impact across scales to frame the adaptive logic and necessary resources that will determine the efficacy of any adaptive strategy.

Mechanisms to build adaptive capacity

The process of synthesising data generated from the four methods described involved tabulating constraints on adaptive capacity identified in each of the four reports (Bussey et al. 2012; Richards et al. 2012; Roiko et al. 2012; Sano et al. 2012) and generating options for enhancing adaptive capacity. These constraints and options were categorised according to three general determinants frequently identified in the BBNs: community resilience and well-being, institutions and policy, and finance.

Clearly, these categories are interrelated. For example, available finance and policy frameworks can constrain or enhance adaptive capacity within communities; at the same time, social capital within communities can strengthen or limit the development and implementation of effective adaptation policies. In this sense, community resilience and well-being could be conceptualised as a goal identified by stakeholders as well as a resource for enhancing adaptive capacity. Finance, institutions and policy are also resources for enhancing the resilience and well-being of communities.

Some specific constraints arise in relation to more than one general determinant, for example, an increasing number of lone and one-parent households identified in the social trends study (Roiko et al. 2012) has implications for community resilience and well-being, finance and institutional/policy, with separate options for enhancing adaptive capacity in relation to each domain (Table 3).

Over twenty constraints on adaptive capacity were identified in this way (Table 4). Constraints were analysed and options to address them were then proposed (Table 5). These options were also discussed and validated with sector research leaders.

Community resilience and well-being

Analysis of the constraints and corresponding options for enhancing adaptive capacity in the domain of community resilience and well-being shows that the majority is related to developing cultural and human capital. In the field of community development, human capital is conceptualised as the capacity of individuals to access skills, knowledge and resources for the purpose of community building and the ability of leaders to foster healthy communities (Emery and Flora 2006). Cultural capital encompasses how people know their world and act in it, which voices wield power, and how innovation is supported (Emery and Flora 2006). Developing knowledge and understanding about vulnerability to climate change impacts is necessary for improving adaptive decisions at the individual and household levels. Enhancing adaptive capacity at the level of a socio-ecological system requires, in addition to the need to understand the vulnerabilities to climate change of particular groups, knowledge of the systemic effects of climate change and the benefits for community well-being of innovative approaches to development. For example, recognising the benefits of maintaining ecosystem services in the face of ongoing land development pressures would represent a shift from values currently dominant in the SEQ region to ones supportive of innovative adaptation. Opinion leaders in the region may play a role in this transition (Keys et al. 2009). A sample of constraints on adaptive capacity in the area of community resilience and well-being, and options for enhancing adaptive capacity is shown in Table 6.

Finance

A lack of access to finance for adaptation measures was identified primarily in relation to lone and one person households and coastal biodiversity. In the case of vulnerable households, specialised finance and/or tax incentives to meet the costs of adaptation are recommended. Where sea level rise threatens coastal biodiversity, funding is required to focus on biodiversity management projects likely to better manage the conflicts between development and conservation, as well as the acquisition of land to protect sensitive ecosystems and/or allow for coastal ecosystem to migrate landward (Shoo et al. 2012). Recent major flooding events in SEQ highlight an additional opportunity identified for a climate-adapted insurance market to reduce investment in areas at risk, particularly in coastal areas (Sano et al. 2012). The option for the State government to work further with property insurers to ensure that the risk of investment in these areas is reflected in the cost of insurance is suggested. Since the completion of this project, state government budget cuts across government departments have been announced that potentially undermine the funding component of adaptive capacity identified by stakeholders in these workshops. Of concern are programs that facilitate the development of adaptive capacity in the areas of natural resources management, energy and water supply and environmental protection (Herald Sun 2012). Environmental stressors associated with climate change, such as flooding, have been identified as potentially transformative for the institutions charged with planning for climate change (Matthews 2012). However, it is still unclear whether climate change is viewed as a transformative stressor by decision-makers in the recently elected state government.

Institutions and policy

Constraints on adaptive capacity in relation to institutions and policy fall into two categories: those that involve the capacity of institutions themselves to adapt, as well as broader adaptive options that are the responsibility of current institutions, particularly government, to implement. For example, policy and planning commitment to climate adaptation planning, biodiversity conservation, coastal zone management and community well-being have been adopted at every level of government in the SEQ region. Some examples of options for enhancing adaptive capacity consistent with existing institutional commitments are illustrated in Table 7. However, institutions may face challenges relating to credibility and leadership (as identified through the historical cases), particularly in relation to complex and uncertain sustainability issues, which may ultimately affect the effectiveness of their programs. These challenges may also present obstacles for community-based organisations involved in sustainability endeavours (Pero and Smith 2008).

Climate change requires that stakeholders consider both short-term and relatively easy to implement measures along with more ambitious long-term engagements with individual, community and institutional culture. For example, enhancing awareness and understanding about climate change risks among vulnerable groups could be achieved in the short-term through existing community governance networks. In contrast, influencing societal values to give greater priority to biodiversity retention over land development would require ongoing education about the systemic benefits for community well-being, in order to achieve a shift in commonly held values and political priorities. Examples of options over various time-scales are shown in Table 8. Short-term mitigative adaptation strategies have a higher degree of success because the adaptive capacity is much more aligned to current norms and institutional priorities. The further the adaptation strategy moves from such norms and priorities, the greater is the decline in adaptive capacity (e.g. a decline in institutional and social imagination, and the political will, to see such adaptation strategies through). Thus, the relationship between knowledge and action is mediated by a range of factors that determine the feasibility of any adaptation recommendation.

Conclusion

A society’s ability to adapt influences its long-term resilience. Historical case studies illustrate how particular adaptations can enhance or erode socio-ecological systems (Nelson 2011; Bussey et al. 2012). How the threats and issues relating to adaptation are framed is central to the ability to respond proactively. This framing of issues is shaped by contextual pressures such as available resources and demography; a range of socio-cultural determinants such as leadership and the complexity and scale of the issues; and the attitudes, values and knowledge of key decision-makers.

This paper has explored the adaptive capacity dimensions that impact on the effectiveness of various adaptation strategies. It has described a four stage methodology used to explore the related domains of socioeconomic trends, historical case studies, systems conceptualisation, and stakeholder perceptions and beliefs. This approach to analysing influences on adaptive capacity had several advantages. Firstly, it synthesised insights on generic determinants of adaptive capacity to frame the identification of specific elements relevant to the adaptation process within each case study area and sector. Secondly, the community-based workshops created a platform for cross-sectoral discussion between stakeholders involved in the decision-making process, supporting the process of mainstreaming climate change adaptation in local areas and sectors within a region. Importantly, the workshops fostered the ability of stakeholders to identify relevant elements of the adaptation process by shifting from linear cause–effect models to complex systems thinking. In addition, participation by stakeholders in subjective evaluations of priority issues for adaptive capacity and the variables affecting them, through BBN modelling, highlighted the values-based nature of enhancing adaptive capacity. Ultimately, the engagement of policy makers as stakeholder participants in collective system conceptualisations and in the development of BBNs provides a pathway for an improved science policy interface.

This paper builds on the growing literature on regional determinants of adaptive capacity. For example, in comparing adaptive capacity determinants across peripheral and central settlements in industrialised Nordic countries, Keskitalo et al. (2011) found that urban centres, such as Stockholm, dependent on well-developed infrastructure, can be highly vulnerable to disruption of that infrastructure from climate-related events. Similarly, rapid population growth in the SEQ region is increasing pressure on infrastructure. In addition, vulnerable groups such as the aged, lone households, one-parent households and those residing in the highly exposed coastal zone are particularly at risk. Keskitalo et al. (2011) also identified the primacy of institutional determinants, particularly the perceived need by stakeholders for improved collaboration and coordination of knowledge and policy across scales of governance. As described in this paper, the opportunity exists for social learning across institutions and their leaders for enhancement of adaptive capacity and community resilience. However, SEQ stakeholders also identified funding, for example, to enable conservation of biodiversity and ecosystem services, to be a critical determinant of adaptive capacity.

Whilst adaptation to climate change will be costly, the main impediments to adaptation are cultural rather than structural. This study demonstrates the combination of physical, social, financial, institutional and cultural constraints that need to be understood when organisations, communities and individuals assess, learn and prioritise how adaptation is to occur.

References

Adger WN (2003) Social capital, collective action, and adaptation to climate change. Econ Geogr 79:387–404

Adger WN (2006) Vulnerability. Glob Environ Change 16(3):268–281

Adger WN, Arnell NW, Tompkins EL (2005) Successful adaptation to climate change across scales. Glob Environ Change Part A 15(2):77–86

Bates MJ (2005) Information and knowledge: an evolutionary framework for information science. Inf Res 10(4):10–14

Beck U (2009) World at risk. Polity, London

Berkes F, Colding J, Folke C (eds) (2003) Navigating social-ecological systems: building resilience for complexity and change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Blackmore C (2007) What kinds of knowledge, knowing and learning are required for addressing resource dilemmas? A theoretical overview. Environ Sci Policy 10(6):512–525

Burley J, McAllister R, Collins K, Lovelock C (2012) Integration, synthesis and climate change adaptation: a narrative based on coastal wetlands at the regional scale. Reg Environ Change 12(3):581–593

Bussey M, Carter R, Keys N, Carter J, Mangoyana R, Matthews J, Nash D, Oliver J, Richards R, Roiko A (2012) Framing adaptive capacity through a history-futures lens: lessons from the South East Queensland Climate Adaptation Research Initiative. Futures 44(4):385–397

Charniak E (1991) Bayesian networks without tears. AI Mag 1(12):50–63

Christian D (2003) World history in context. J World Hist 14(4):437–458

Diamond J (2005) Collapse: how societies choose to fail or succeed. Viking, New York

Emery M, Flora C (2006) Spiraling-up: mapping community transformation with community capitals framework. Community Dev J Community Dev Soc 37(1):19–35

Ferguson N (2010) Complexity and collapse: empires on the edge of chaos. Foreign Aff 89(2):18–32

Ford JD, Smit B, Wandel J (2006) Vulnerability to climate change in the Arctic: a case study from Arctic Bay, Canada. Glob Environ Change 16:145–160

Goleman D (2000) Leadership that gets results. Harv Bus Rev 78(2):78–93

Halal WE (2008) Technology’s promise: expert knowledge on the transformation of business and society. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Heifetz R, Grashow A, Linsky M (2009) The practice of adaptive leadership: tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world. Harvard Business Press, Watertown, MA

Herald Sun (2012) Full list of Queensland public service redundancies. Herald Sun 11 September 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2012, from http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/national/full-list-of-queensland-public-service-redundancies/story-fndo45r1-1226471881372

Hinkel J (2011) Indicators of vulnerability and adaptive capacity: towards a clarification of the science–policy interface. Glob Environ Change 21:198–208

Jakku E, Lynam T (2010) What is adaptive capacity? Report for the South East Queensland Climate Adaptation Research Initiative Brisbane, CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems

Juntti M, Russel D, Turnpenny J (2009) Evidence, politics and power in public policy for the environment. Environ Sci Policy 12(3):207–215

Keskitalo ECH, Dannevig H, Hovelsrud GK, West JJ, Swartling ÅG (2011) Adaptive capacity determinants in developed states: examples from the Nordic countries and Russia. Reg Environ Change 11(3):579–592

Keys N, Thomsen DC, Smith TF (2009) Opinion leaders and complex sustainability issues. Manag Environ Quality 21(2):187–197

Landes D (2007) Slow surprise: the dynamics of technology synergy. In: Fukuyama F (ed) Blindside: how to anticipate forcing events and wild cards in global politics. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp 23–28

Lee K (1993) Compass and gyroscope: integrating science and politics for the environment. Island Press, Washington DC

Lorenzoni I, Jordan A, Hulme M, Turner RK, O’Riordan T (2000) A co-evolutionary approach to climate change impact assessment: Part I. Integrating socio-economic and climate change scenarios. Glob Environ Change 10:57–68

Matthews T (2012) Responding to climate change as a transformative stressor through metro-regional planning. Local Environ Int J Justice Sustain. doi:10.1080/13549839.2012.714764

Measham TG, Preston BL, Smith TF, Brooke C, Gorddard R, Withycombe G, Morrison C (2011) Adapting to climate change through local municipal planning: barriers and challenges. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 16:889–909

Nelson DR (2011) Adaptation and resilience: responding to a changing climate. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Change 2(1):113–120

Orr D (2002) The nature of design: ecology, culture and human intention. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Pelling M (2011) Adaptation to climate change: from resilience to transformation. Routledge, London

Pero LV, Smith TF (2008) Institutional credibility and leadership: critical challenges for community-based natural resource governance in rural and remote Australia. Reg Environ Change 8(1):15–29

Ponting C (2007) A new green history of the world: the environment and the collapse of great civilizations. Vintage, London

Preston B, Brooke C, Measham TG, Smith TF, Gorddard R (2009) Igniting change in local government: lessons learned from a bushfire vulnerability assessment. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 14:251–283

Quezada G, Grozev G, Wang C-h, Seo S (2012) Managing the peak—adapting electricity demand to regional climate change and population growth (personal communication)

Ravetz J (2011) Postnormal science and the maturing of the structural contradictions of modern European science. Futures 43(2):142–148

Richards R, Sano M, Roiko A, Carter RW, Bussey M, Matthews J, Smith TF (2012) Bayesian belief modeling of climate change impacts for informing regional adaptation options. Environ Model Softw. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2012.07.008

Roiko A, Mangoyana RB, Oliver J, McFallan S, Carter RW, Smith TF (2012) Socio-economic trends and climate change adaptation: the case of South East Queensland. Aust J Environ Manag 19(1):39–50

Sano M, Richards R, Carter RW, Roiko A, Matthews J, Bussey M, Thomsen DC, Smith TF (2012) Identifying pathways towards effective climate change adaptation: a systems approach (personal communication)

Shoo L, O’Mara J, Perhans K, Rhodes JR, Runting R, Schmidt S, Traill LW, Weber L, Wilson K, Lovelock C (2012) Moving beyond the conceptual: specificity in regional climate change adaptation actions for biodiversity in South East Queensland, Australia. Reg Environ Change. doi:10.1007/s10113-012-0385-3

Smit B, Pilifosova O (2001) Adaptation to climate change in the context of sustainable development and equity. Climate change 2001: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. J McCarthy 879–906

Smith TF, Brooke C, Preston B, Gorddard R, Abbs D, Mcinnes K, Withycombe G (2007) Managing for climate variability in the Sydney region. J Coastal Res S1(50):109–113

Smith TF, Brooke C, Preston B, Gorddard R, Abbs D, McInnes K, Withycombe G, Morrison C (2009) Managing coastal vulnerability: new solutions for local government. In: Dahl E, Moksness E, Støttrup J (eds) Integrated coastal zone management. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, UK, pp 331–340

Smith TF, Lynam T, Preston BL, Matthews J, Carter RW, Thomsen DC, Carter J, Roiko A, Simpson R, Waterman P, Bussey M, Keys N, Stephenson C (2010) Towards enhancing adaptive capacity for climate change response in South East Queensland. Aust J Disaster Trauma Stud 2010(1). http://trauma.massey.ac.nz/. Accessed 25 Apr 2012

Smith TF, Thomsen DC, Keys N (2011) The Australian experience. In: Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L (eds) Climate change adaptation in developed nations: from theory to practice, vol 42. Springer, Dordrecht

Stevenson T (2002) Anticipatory action learning: conversations about the future. Futures 34:317–325

Tàbara JD, Pahl-Wostl C (2007) Sustainability learning in natural resource use and management. Ecol Soc 12(2):3

Tainter JA (1998) The collapse of complex societies. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Thomsen DC (2008) Community-based research: facilitating sustainability learning. Aust J Environ Manag 15(4):222–230

Traill LW, Perhans K, Lovelock CE, Prohaska A, McFallan S, Rhodes JR, Wilson KA (2011) Managing for change: wetland transitions under sea-level rise and outcomes for threatened species. Divers Distrib 17(6):1225–1233

Uusitalo L (2007) Advantages and challenges of Bayesian networks in environmental modelling. Ecol Model 203(3–4):312–318

Vincent K (2007) Uncertainty in adaptive capacity and the importance of scale. Glob Environ Change 17(1):12–24

Wang X, Stafford Smith DM, McAllister RRJ, Leitch A, McFallan S, Meharg S (2010) Coastal inundation under climate change: a case study in South East Queensland. CSIRO, Brisbane

Wright R (2006) A short history of progress. Da Capo Press, Cambridge, MA

Yohe G, Tol RSJ (2002) Indicators for social and economic coping capacity—moving toward a working definition of adaptive capacity. Glob Environ Change 12(1):25–40

Acknowledgments

This research is part of the South East Queensland Climate Adaptation Research Initiative, a partnership between the Queensland and Australian Governments, the CSIRO Climate Adaptation National Research Flagship, Griffith University, University of the Sunshine Coast, and University of Queensland. The initiative aims to provide research knowledge to enable the region to adapt and prepare for the impacts of climate change.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Keys, N., Bussey, M., Thomsen, D.C. et al. Building adaptive capacity in South East Queensland, Australia. Reg Environ Change 14, 501–512 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-012-0394-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-012-0394-2