Abstract

Patient participation is highlighted in healthcare policy documents as an important area to address in order to improve and secure healthcare quality. The literature on healthcare quality and safety furthermore reveals that transitional care carries a risk of adverse events. Elderly persons with co-morbidities are in need of treatment and healthcare from several care professionals and are transferred between different care levels. Patient-centered care, shared decision-making and user involvement are concepts of care that incorporate patient participation and the patients’ experiences with care. Even though these care concepts are highlighted in healthcare policy documents, limited knowledge exists about their use in transitions, and therefore points to a need for a review of the existing literature. The purpose of the paper is to give an overview of studies including patient participation as applied in transitional care of the elderly. The methodology used is a literature review searching electronic databases. Results show that participation from elderly in discharge planning and decision-making was low, although patients wanted to participate. Some tools were successfully implemented, but several did not stimulate patient participation. The paper has documented that improvements in quality of transitional care of elderly is called for, but has not been well explored in the research literature and a need for future research is revealed. Clinical practice should take into consideration implementing tools to support patient participation to improve the quality of transitional care of the elderly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

There is a fast‐growing elderly population worldwide (WHO 2011a, b) often with several medical diagnoses and with an increasing need for clinical care across primary and secondary healthcare. This complex need for care and treatment is often caused by chronic diseases, physical disability, cognitive impairments and polypharmacy (Foss and Askautrud 2010; McCall et al. 2008) and require the elderly patients to transfer between different levels of healthcare, with an increasing risk of fragmented care and adverse events (Coleman et al. 2005; Danielsen and Fjær 2010). Awareness, involvement of qualified healthcare professionals and comprehension of the task distribution at different levels of the healthcare system are needed to ensure quality in the treatment and care of the elderly (Aase and Testad 2010). Over the last decades, patient participation in healthcare has been emphasized in health policy documents in Europe and globally, and the patient perspective is a main area of WHO’s Patient Safety Strategy (WHO 2011a, b).

Transitional care is described by Coleman and Boult (2003) as a set of actions ensuring the coordination and continuity of healthcare as patients transfer between different levels of care within the same location or between locations; i.e., admission to and discharge from specialist healthcare (hospital) to community care and elderly home care facility (Coleman and Boult 2003; Laugaland et al. 2012). Many transitions are unplanned and patients and family members are unprepared. In addition, inadequate discharge planning often leads to readmission (Huber and McClelland 2003). The patients and their caregivers are most often the only common and stable factor moving across different levels and sites of care (Coleman et al. 2004). Involvement and participation of elderly in transitional care has been suggested as one way of preventing adverse events and improving the quality of transitional care (Foss and Hofoss 2011; Huber and McClelland 2003).

Healthcare quality is by patients and relatives characterized as individualized, patient-focused care, attending to the needs and concerns of the patient and provided through a caring and committed relationship between staff and patient, demonstrating patient involvement and participation (Attree 2001). User or patient participation is defined by WHO (2011a, b) as the patient’s right to participate in decision-making concerning level of care and where to live. Patient participation involves sharing of information, power transfer from nurse to patient, intellectual and/or physical activities and the benefits of these activities (Cahill 1996). Patient collaboration is a matter of cooperation between patient and provider. Patient-centered care and shared decision-making incorporate patient participation and the patients’ experiences with care. The Quality Chasm’ report defines “patient centeredness” as staff providing care that is respectful and responsive to the individual patient’s preferences, needs, encouraging patient involvement in care and decision-making. Shared decision-making is suggested as one useful tool placing the person in the center of care (IOM 2001). It aims to increase patients’ knowledge and control over treatment decisions by involving both the patient and the service provider in the decision-making about treatment and care (Storm and Edwards 2012). To achieve shared decision-making, there has to be a partnership between provider and patient where the provider listen to and respect the patient’s views about their health, where both parties share information, discuss diagnosis, treatment and care needs in order to maximize the patient’s opportunities and abilities to make decisions and respect the patient’s decisions (Godolphin 2009).

In the present study, we examine patient participation in the specific context of elderly patients’ involvement and participation in transitional care. It involves patients and healthcare professionals sharing information about medical concerns, diagnosis, prognosis, medications and relief measures. It includes considering the patient’s views and wishes at admission to or discharge from hospital. It also includes patient involvement in care planning and decision-making about; time of discharge, whether to go home or to a care home, follow-up care, physiotherapy and other vital decisions. There is limited knowledge about how patient participation is adapted to transitional care for the elderly, and how patient-centered care and shared decision-making models of patient participation are integrated (Storm et al. 2012). This paper therefore provides an overview of the existing literature describing patients’ participation in transitional care as well as different tools for supporting it.

2 Aim of the study

The overall aim of the study was to give an overview of the existing literature on elderly patients’ participation in transitional care. Hence, the following key research question is addressed in the study:

What are the key issues reported in the literature that influence on elderly patients’ participation in transitional care?

3 Methodology

3.1 Literature review and data collection

A literature review was performed, using the 27 point Prisma Checklist of the relevant literature (Moher et al. 2009). An integrative approach was used including the literature with multiple research designs and methodologies (Whittemore et al. 2005).

3.1.1 Databases

The literature searches were performed in the electronic databases Cinahl, Medline, Academic Search Elite, Scopus, ISI Web of Science and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. These databases were considered most appropriate for our literature searches as they provide peer-reviewed articles within the field of health and social sciences. The search was done performing an open-ended search with the terms “patient participation” or “consumer participation” or “patient-centered care” or “user involvement” or “shared decision*” in Cinahl, Medline and Academic Search Elite. The search words were combined with “transitional care” or “care transit*” or “patient transfer” or “handover” or “admission” or “discharge” and combined with “elder*” or “aged” or “old*”. Then searches with all the search terms were conducted in Cochrane, Scopus and ISI Web of Science. The terms “patient participation”, “patient transfer” and “aged” were chosen as they are MeSH words. The other search words were used due to their relevance to our study. The Cochrane database was searched in order to find review articles including empirical studies that could be relevant to our study. The search was performed with the string spelled out in all 6 databases, but in ISI, we excluded the last conjunct, as the search otherwise yielded no results.

3.1.2 Inclusion criteria and search strategy

Titles, abstracts and full-text articles were analyzed independently by two researchers to ensure that all relevant studies were retrieved, according to the inclusion criteria; i.e., (1) articles from January 1, 2000 until September 15, 2012, (2) English language, (3) search terms, (4) peer-reviewed articles published in scientific journals and (5) content: elderly patients’ participation in transitional care between different levels of care or between locations to improve the quality of care. Patient-centered care and shared decision-making were used as search terms as these incorporate patient participation and the patients’ experiences with care. These concepts were combined with terms synonymous to “transitional care” and “elderly” as presented in Table 1.

3.2 Review sample

The flow diagram for reaching the final sample with articles included in the review is presented in Fig. 1 (Moher et al. 2009).

Excluded studies (550) from the Ebscho Host search engine (Cinahl, Academic Search Elite, Medline), Cochrane, Scopus, ISI Web of Science and hand searches were either studies of mental health, transition to a hospice, transition within healthcare institution or the study did not address patient participation, according to our definition. A total of 204 abstracts were read independently by two researchers. Sixty-five full-text articles were assessed for eligibility and 30 studies were included in this review. Fifteen studies were on patient experiences with participation in transitional care and 15 on tools to support elderly patients’ participation in transitional care.

3.2.1 Analysis

Thematic synthesis was used in this review to explore the current research question (Polit and Beck 2008). For studies on elderly patients’ participation in transitional care, each article was summarized according to the following items: study (author, year, country and journal), aim, definition patient participation, design, participants, recruitment, results, implication/contribution and reported credibility. For studies on tools to support patient participation in transitional care, the review sample was analyzed according to the following items: study (author, year, country and journal), tool/intervention, definition patient participation, study design, outcome focus, participants, results, reported validity and reported reliability. For the review, sample information on country of first author and publication year was reported.

4 Results

In the first part, studies exploring elderly patients’ participation in transitional care are reported. In the second part, studies on tools to support elderly patients’ participation in transitional care are presented.

4.1 Elderly patients’ participation in transitional care

Studies included were designed to describe elderly patients’ participation in discharge and rehabilitation planning. All sixteen studies included older patients, age span from 60 and older. The sample size varied from eight to 3,538 participants. All studies explored elderlies’ participation in the discharge process. Eleven studies were performed by semi-structured interviews focusing on the discharge process, three were observation studies of discharge meetings with follow-up interviews (Hedberg et al. 2008; Huby et al. 2004, 2007) and two used a quantitative questionnaire followed by qualitative interviews (Roberts 2002; Somme et al. 2008). Of the fifteen articles, four included the carers or the relatives (Ellis-Hill et al. 2009; Hedberg et al. 2008; Roberts 2002; Rydeman and Törnkvist 2009) and three had a dual perspective on both patient and professional carers (Hedberg et al. 2008; Huby et al. 2004, 2007). The studies were published in nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and public health journals. Some studies specified the diagnoses, which varied from medical diagnoses such as stroke or orthopedic diagnoses such as lower limb or hip fractures, while some studies referred to ordinary rehabilitation patients. The concept “participation” was defined in five studies (Table 2).

Included studies most often had a patient perspective and were related to participation in discharge planning. Analysis revealed the following main categories: information, participation in discharge planning, formal assessment on functional ability, paternalism, disempowerment, the content meaning of participation, “good” experiences of transitional care and family support.

4.1.1 Information

Lack of information concerning the discharge process was apparent in several of the studies exploring the patients’ perspective on discharge planning (Benten and Spalding 2008; Ellis-Hill et al. 2009; Foss and Hofoss 2011; McKain et al. 2005; Perry et al. 2011; Swinkels and Mitchell 2008). Information was provided orally. In one study by Benten and Spalding (2008), written information had been provided as an information leaflet covering the purpose and goal of the intermediate care unit. Despite this none of the elderly patients had been informed about intermediate care, before it was suggested by professionals that they were to be transferred. Service users therefore lacked the understanding and the awareness of the potential and the goals of the intermediate care services. McKain et al. (2005) also reported patients receiving very little information about what to expect on admission to a rehabilitation unit.

Two studies (Perry et al. 2011; Swinkels and Mitchell 2008) documented that some patients were not aware of their own formal discharge plan. One study (Foss and Hofoss 2011) revealed sparsely information to patients about discharge. This was in contrast to Almborg et al. (2008) who found that the elderly patients felt they had received sufficient information about their illness, tests, examinations, medication, rehabilitation and possibility to ask questions.

4.1.2 Participation in discharge planning

Minimal participation in the discharge process was reported in several studies (Almborg et al. 2008; Benten and Spalding 2008; Foss and Hofoss 2011; Perry et al. 2011; Somme et al. 2008). Swinkels and Mitchell (2008) focused on elderly patients’ perceptions of effects of delayed transfer into the community, involvement in discharge planning and future community care needs. Decision about transfer to a residential or nursing care was, according to the patients, taken by healthcare professionals. This led to feelings of distress and several patients speculated about self-discharge.

Benten and Spalding (2008) investigated the experiences of older people moving from hospital to intermediate care. The authors found that few participants felt they were involved or participated in the decision-making process. Patients thought that the main reason for transfer was that they were “bed-blockers” and did not know that they were enrolled in an active rehabilitation program.

Perry et al. (2011) revealed lack of shared decision on when to go home and dependence on family to feel confident. Some patients expressed the view that they could not go home unless a formal or informal care was arranged. The elderly patients trusted the health services system, they did what they were told and did not complain. Patients could not actively take part in decision-making plans, as they were not aware of the formal discharge plans.

Gibbon (2004) found that many patients expressed a desire to go home as soon as possible, but worried about how to cope and they wanted to be cared for by the family. The staff had a weekly team conference, but the patients were not invited. This made the patients passive in goal setting and action planning. The author suggests that professionals were uncomfortable with or feared having unrealistic aims about the patient recovering from stroke.

4.1.3 Formal assessment on functional ability

The purpose of Huby et al.’s case study (2007) was to understand how elderly patients experienced participation and how professionals enacted participation in discharge planning. They found a procedurally driven care, not comprising decision-making. Discharge planning sometimes started on admission, but relied to a large extent on formal assessments. The use of formal assessments of the patients’ health condition produced patterns of involvement which “broke down each patient’s identity into a collection of graded physical and cognitive abilities and made it difficult to include patient-centered views on independence” (p. 63).

In Benten and Spalding’s study (2008), most patients were not aware of rehabilitation goals being set for them. The rehabilitation concept was seen as little purposeful for active rehabilitation; nevertheless, some were involved in preparation for going home. Most of them were not aware of a formal assessment of their physical, personal or social needs, or rehabilitation goals on admission.

Huby et al. (2004) documented that goal settings for rehabilitation were set by physiotherapists and occupational therapists together with the patients. However, since patients were not present at the meetings, staff had limited information about the patients’ competence to manage on their own, according to cognitive and physical ability. This inhibited communication between staff and the patients. Staff explained lack of patient participation as due to lack of patient motivation when they failed to engage the patient in the rehabilitation goals, although the patients had clear thoughts about how to cope with the situation. Huby et al. (2004) raised the question “whether the patients failed to engage in the system, or whether the system of care failed to engage the patient” (p 128).

4.1.4 Paternalism

Several studies revealed a paternalistic approach, but few used the term “paternalism” (Almborg et al. 2008; Ellis-Hill et al. 2009; Perry et al. 2011). A paternalistic medical model was suggested by Almborg et al. (2008) as participants to a limited degree experienced participation in medical treatment decision-making. Contact with health professionals was characterized as one-way communication in order to inform patients (Perry et al. 2011). Some professionals explained it as “the patients did not want to be involved in discussions concerning their treatment” (Almborg et al. 2008, p 205).

Hedberg et al. (2008) conducted observations of inter-professional care-planning meetings. Study results showed that patients needed communicative alliances with family members or other participants when negotiating their needs and desire for further care. There were illustrations of how professionals attempted to persuade the patients to accept their suggestions, and nurses that did not support the patients’ wishes during the care plan meetings. The study revealed a need of further knowledge on how to involve vulnerable patients in communication.

Foss and Hofoss’ (2011) results suggest that the elderly patients preferred participation, but they did experience few opportunities to speak, to be heard, and to be involved in shared decisions and therefore not often experienced “real participation”.

4.1.5 Disempowerment

Not involving patients in decisions concerning their own treatment, care or discharge process may lead to disempowerment of patients (Benten and Spalding 2008). Swinkels and Mitchell (2008) reported patients’ experiences of depression, change in functional ability, dependence on others, hopelessness, apathy, grief and loss of personal autonomy. Patients felt imprisoned in hospital and disempowered, but despite this several speculated about self-discharge.

When professionals had an unstructured approach, they were often task-oriented, and the patients’ individual needs risked being unsatisfied. Patients and relatives did not feel they were heard or seen and they felt not involved in the discharge planning process. Patients felt resignation and powerlessness when they experienced that professionals had made up their mind before discussing with patients and their family and being discharged when feeling unprepared (Rydeman and Törnkvist 2009).

4.1.6 The content meaning of participation

Huby et al. (2004, 2007) found that the concept participation was unknown among the participants and did not have a useful meaning to them. Patients also lacked understanding of the language used by professionals and the purpose of rehabilitation in the discharge planning meetings. There was a link between participants’ reduced ability to take part in decisions and their frailty making them more dependent on others to make decisions on their behalf.

Roberts (2001, 2002) found that the majority of the patients felt they were involved in decisions about discharge from hospital and had opportunities to express their wishes to healthcare staff, although some patients let the professionals make decisions on their behalf. This was in contrast to interview results where one elderly patient revealed what the meaning of participation could entail by saying: “they’ve told me what they were going to do, and they’ve done it” (Roberts 2002, p. 413). The participants were not involved in transitional care, except for being informed and they understood this as participation.

4.1.7 “Good” experiences of participation in transitional care

Ellis-Hill et al. (2009) reported that patients perceived discharge as successful when they felt informed. The authors argued that sharing of information gave patients more understanding of service decisions and possibilities, resulting in a more honest and less paternalistic approach.

Rydeman and Törnkvist (2009) showed that patients felt prepared for life at home when their needs were met such as caring issues, activities of daily living and where to return. Feeling prepared was explained as having a satisfactory understanding of how life at home would be. It was important for the participants that professionals had preparation skills and used a guiding approach, meaning that the professionals gave individual information, instructions regarding disease and treatment and discharge time scale. When the elderly’s views were considered and there was time available for conversation, patients felt involved and secure in the discharge process.

4.1.8 Family support

Some studies had a patient and carer perspective documenting the seemingly advantageous position of elderly patients having their family or carer present to support and articulate their needs (Ellis-Hill et al. 2009; Hedberg et al. 2008; Roberts 2002; Rydeman and Törnkvist 2009). Roberts (2002) found that only half of the older participants in the study had their relatives present in the discharge meeting. Family members often stayed by the patients during or after discharge. It made the patients feel safe and could for example prevent newly operated patients from falling. Family support was crucial, although the patients did not want to burden their relatives (Perry et al. 2011). When professionals had a guiding approach to the older persons and their families they felt involved and secure in the discharge process, that they were heard and their views were considered (Rydeman and Törnkvist 2009).

4.2 Tools to support elderly patients’ participation in transitional care

ToolsFootnote 1 to support elderly patients’ participation in transitional care were all implemented as part of discharge planning and rehabilitation. All fifteen studies included older patients and the sample size in each study varied from seven participants to 310. Five studies used a quantitative design and were carried out as an intervention (Bull et al. 2000; Coleman et al. 2004; Jangland et al. 2012; Preen et al. 2005; Watkins et al. 2012). Eight studies had a qualitative approach, using semi-structured interviews (Brooks 2002; Clarke et al. 2010; Efraimsson et al. 2006; Moats 2007), a combination of semi-structured interviews and focus groups (Griffith et al. 2004; Reed and Stanley 2003), observation (Grimmer et al. 2006a) and in combination with video-recorded meetings and follow-up interviews (Efraimsson et al. 2004). Two studies were performed using both a quantitative and a qualitative approach (Grimmer et al. 2006b; Parry et al. 2008). Four studies defined patient participation. An overview of included studies and methodological approach is presented in Table 3.

The review revealed several measures and interventions developed and implemented to support patient participation in discharge of elderly patients. The introduction of these tools resulted in both positive and negative experiences and outcomes.

4.2.1 Family meetings

Griffith et al.’s study (2004) was on family meetings, involving family members, the patient and hospital personnel in discussions concerning the patient’s illness, treatment and discharge plans. The goal was to explore opinions of the participants in order to improve the quality of care planning. Several patients reported that they had no opportunity to participate in family meetings. Six out of sixteen patients had not been informed about the family meeting being arranged for them. Furthermore, there was a lack of informed consent and lack of clarity of the purpose of family meetings. These results suggested a need for a family meeting model with a clear agenda for the meetings, a documented informed consent from the patient, purpose with the meeting and support for the patient to express their own views.

4.2.2 Discharge care plans

The Care Transition Intervention (Coleman et al. 2004; Parry et al. 2008) is patient-centered and rooted in principles of self-management and continuity. The intervention comprised four conceptual areas: medication self-management, a patient-centered record, primary care and specialist follow-up, education about “red flags” or warning symptoms indicating worsening health condition. The intervention was carried out using a personal health record and a transition coach providing follow-up telephone calls and home visits to ease the care transition. Results showed reduced readmissions. Patients also reported confidence in managing their condition and medications and in communication with healthcare staff (Coleman et al. 2004; Parry et al. 2008). Reed and Stanley (2003) conducted a study with a user-led daily living plan (DLP) to promote person-centered care and to stimulate effective person-centered communication between the hospital and the care home. Implementation of the DLP plan resulted in a more positive feeling among the older patients about the discharge process pointing to the need for developing a discharge plan from the start of the hospital stay.

Another discharge care plan (Preen et al. 2005) included problems identified from hospital notes and patient/care-giver consultation, goals developed with the patient/caregiver on personal circumstances and identified interventions and community service providers who met patient needs. Results from patient surveys showed that satisfaction with input into discharge care planning was significantly greater for patients receiving the care plan compared with the control group. Two studies (Efraimsson et al. 2004, 2006) described the communication at the discharge planning conference (DPC). DPC is a meeting between professionals and patients aimed to co-ordinate resources and to enhance patient involvement in care. Only a few patients were invited to participate and negotiate in the DPC, some chose to not participate or was excluded from the discussions, and were unable to influence on their own situation. Another aspect was the feeling of being in focus at the DPC. Although the participants were grateful, they also felt that their dependence and disability were publicly exposed. They were expected to decide what help they wanted after discharge, without knowing what resources offered, lack of knowledge about the care system, including health professionals’ role in decision-making.

4.2.3 Checklists

Grimmer et al. (2006a) developed a practical discharge planning checklist from patient and carer concerns when preparing for discharge, providing an opportunity for shared decision-making about daily living. The list was developed to assist with the practicalities of coping at home after discharge. The checklist covered the following areas: safe transport from hospital to home, cash to pay medications, assessing and access to medical care, the use of activity aids such as a walking frame, someone around to care for the patient and the caring responsibility. The checklist was evaluated with patients having received it within 24 h after admission to hospital as an adjunct to formal discharge planning. Results indicated that some patients felt too tired and unwell to consider the practicalities of returning home. Despite this the checklist improved patients’ preparedness for discharge and family involvement (Grimmer et al. 2006b).

The “Tell-us card” written by the patient was introduced as an intervention to improve patient participation in a surgical care unit (Jangland et al. 2012). Areas addressed by patients as important at discharge were: information about self-care, information about the operation and follow-up, coordination of care and practical support. The Tell-us card gave significant improvements in participation abilities for patients in nursing and medical care decisions during hospitalization, especially in interaction with nurses. Patients reported significantly higher nursing care quality regarding commitment and respectful treatment; although about half of the patients reported they did not receive useful information about self-care.

4.2.4 Education programs

Implementation of The Transition Program for Frail Older Adults, designed to prevent re-hospitalization, resulted in a positive outcome (Watkins et al. 2012). The program included education of patients about warning signs that may lead to readmission, a what-to-do plan for self-management, reconciling medication regimens and education on appropriate use.

The professional-patient partnership model (Bull et al. 2000) is an intervention to facilitate identification of elderly people’s needs for follow-up care providing an opportunity for interaction and participation between the elderly, caregiver and hospital staff in discharge planning. The intervention contained an educational program for nurses and social workers, a self-administered Discharge Planning Questionnaire (DPQ) for patients, a videotape preparing patients and caregivers for hospital discharge, medication information and a brochure on how to access community healthcare. Patients in the intervention group felt more prepared to manage their own care, they reported receiving more information about their condition, medication, and community services and felt in better health than the control group.

4.2.5 Home visits

Clarke et al. (2010) investigated COPD patients’ experiences with participation in an early supported discharge service (EDS) intervention with daily home visits by a nurse for 3 days, and then as required up to 2 weeks. Results show that patients felt they were discharged from hospital too early, they felt unable to negotiate time of discharge and that life at home was difficult.

Brooks (2002) evaluated a rapid assessment support service (RASS), an inter-professional team providing support to elderly in their own homes, in order to reduce unnecessary emergency admissions. The model dealt with care plans as a support in the home environment and was introduced as a partnership between professionals, carers and patients. The results demonstrated that the evidence of involvement of informal carers enabled older people to stay in their own homes. Their carers were involved in assisting with medications, changing dressings and giving injections and the patients experienced an inclusive, informed, empathetic and patient-centered service. The value of home visits and the importance of being at home also emerged in Moat’s study (2007). The study was a comparison between a client-defined model and a negotiated model for decision-making. Therapists tried to balance the competing issues of patient autonomy and safety concerns. The therapists aimed for client-centered practice, where the client’s wishes were included in the decision-making processes. The authors suggest a client-defined model for decision-making where providers facilitate patient participation in daily life.

5 Discussion

Findings from the literature review revealed that discharges are often accompanied by a lack of information to the elderly patient (Benten and Spalding 2008; Ellis-Hill et al. 2009; Foss and Hofoss 2011; Perry et al. 2011; McKain et al. 2005; Swinkels and Mitchell 2008). Minimal participation when elderlies transfer between different levels of care, more specifically in discharge planning and decision-making related to this was found (Foss and Hofoss 2011; Gibbon 2004; Huby et al. 2004; Perry et al. 2011; Somme et al. 2008; Swinkels and Mitchell 2008). Some studies documented participation to a certain degree in decisions regarding discharge from hospital, having a positive effect on patients’ wellbeing and satisfaction with healthcare (Almborg et al. 2008; Roberts 2001, 2002). The participants were to some extent aware of the complexity of arrangements being provided for them (Swinkels and Mitchell 2008). Potential challenges to ensure patient participation in transitional care are: the patients’ health condition, lack of information, lack of involvement of elderly patients and their families in discharge planning, providers being paternalistic in the decisions on transitional care on behalf of their elderly patients, and the elderly not having a clear understanding of or any preferences for participation (Benten and Spalding 2008; Ekdahl et al. 2009; Grimmer et al. 2006b; Huby et al. 2004, 2007; Roberts 2002). To support patient participation in transitional care, several tools were implemented. Some of these showed positive results (Watkins et al. 2012; Jangland et al. 2012; Reed and Stanley 2003; Brooks 2002). Others had limited effects on participation (Efraimsson et al. 2006, 2004). Although good intentions existed from healthcare professionals to involve patients and improve the discharge process, not all efforts succeeded.

In the healthcare quality literature, patient experiences are recognized as a key area to attend to. Patient centeredness and patient participation is highlighted in policy documents worldwide (WHO 2011a, b). There is a relationship between patients’ participation and their rating of quality of care. Patients reporting more participation are less likely to be admitted to the emergency department and more confident in their ability to express and protect themselves from adverse events (Weingart et al. 2011). Our results show limited participation of elderly in transitional care. Thompson (2007) identified five levels of patient‐determined involvement: noninvolvement, given information, dialogue, shared decision-making and autonomous decision-making, where participation is ranging on the continuum from no participation to autonomous decision-making. According to Thompson’s ladder, information is a prerequisite for active participation. Several of the studies in the review sample show a lack of information provided to patients, and professionals not explaining the meaning of participation to their patients (Benten and Spalding 2008; Swinkels and Mitchell 2008). When information was given, it was sometimes just to inform about decisions already taken by professionals (Efraimsson et al. 2004). “Real participation” belongs to the third and highest step of the ladder and was sparsely found (Thompson 2007). This concept has been explained in one of the studies as a high degree of shared decision (Foss and Hofoss 2011), and some participants experienced to be heard, involved and supported in their needs (Ellis-Hill et al. 2009; Rydeman and Törnkvist 2009). These results show that real participation may be difficult to achieve and that information is necessary for active participation in transitional care of the elderly.

Paternalism was apparent in the studies in different ways. It was demonstrated when professionals having a medical authority used professional language which patients had trouble to understand or when patients accepted being inferior to health professionals and doing what they were told and not complaining (Huby et al. 2004; Perry et al. 2011). This excluded elderly patients from participation in discussions relating to their need for care. Patients that experienced a paternalistic approach seemed according to Almborg et al. (2008) to be the same that did not have any active participation in the discharge process. Paternalism and lack of participation did not seem to concern some of the patients, they did not want to be involved in discussions or decisions about their treatment and care (Almborg et al. 2008; Huby et al. 2004, 2007; Perry et al. 2011), decisions were made for them in their best interest, so they chose to not participate (Ekdahl et al. 2009; Huby et al. 2007). Health providers suggested this attitude was caused by a lack of motivation (Huby et al. 2004, 2007) or that some of the elderly found it difficult to understand what health professionals talked about, they did not feel competent and lacked empowerment (Almborg et al. 2008). Tang and Venables (2000) suggest that the elderly of today are socialized into a patient role where participation sparsely exists and the “ideal patient” is the obedient and passive individual.

The presence of family staying with the patient seemed to be of high importance in several studies. They served as patient advocates and provided assurance for their elders (Ellis-Hill et al. 2009; Hedberg et al. 2008; Roberts 2002; Rydeman and Törnkvist 2009). This may indicate that the patients needed someone to speak for them while being hospitalized and also in transitional care. Education of elderly is suggested in the literature as important to stimulate participation in transitional care (Laugaland et al. 2012; Merten et al. 2011; Storm et al. 2012). In this review, several tools to support elderly patients’ participation in transitional care were identified and reported to have positive impact on the elderly patients. Comprehensive educational transition programs such as the Care Transitions Intervention have been developed and implemented (Bull et al. 2000; Coleman et al. 2004). The Care Transition Intervention prepared patients and caregivers for participation in care delivered across settings and has been effective in supporting patients’ self-management during transitions and reduced readmissions. Re-hospitalization was prevented significantly using a care transition program (Brooks 2002; Watkins et al. 2012). In the same way, the professional-partnership model resulted in fewer days in the hospital when patients were readmitted (Bull et al. 2000). A transitional coach and a personal health record made patients feel comfortable and safe (Coleman et al. 2004; Parry et al. 2008). Home visits revealed the importance of being at home for the elderly patient (Moats 2007), although other patients having COPD felt they were sent home too early (Clarke et al. 2010). A practical patient-centered checklist improved patients’ and families’ preparedness for discharge (Grimmer et al. 2006a, b). User-led daily living plan resulted in more patient-centered communication between hospitals and care homes (Reed and Stanley 2003).

Although several of the studies had positive consequences in terms of reducing readmissions, as increased information and participation using discharge plans (Coleman et al. 2004; Preen et al. 2005) supporting patients’ self-management and increasing preparedness for discharge, and transitional navigators that led to decreased readmissions, patient participation was not achieved in all studies on tools. One reason seemed to be the lack of information about implementation and use of the tool (Jangland et al. 2012; Efraimsson et al. 2004; Griffith et al. 2004). Otherwise discharge seemed to be too early for some patients (Clarke et al. 2010). Tools or interventions in healthcare seem to be implemented in the patients’ best interest, in order to empower patients to participate in discharge planning. To provide input and stimulate participation and finally for the elderly to influence decisions, further efforts are needed. A review of interventions for improving older patients’ involvement show that face-to-face coaching sessions combined with written materials may be one-way forward (Wetzels et al. 2008).

5.1 Limitations

The current review has some limitations. The literature search was limited to year 2000 until September 15, 2012 caused to increase of the elderly population following changes in healthcare and to get the most updated research in the field. The search was comprehensive, but limited to six electronic databases so there is a possibility that published studies fulfilling our inclusion criteria have been missed. An important limitation in this study is that we have done an interpretation of other researchers’ interpretation of their studies. The literature review included only articles published in English. In the review, we focused more on results in the included studies, than on the methodology used. We did not rate methodological quality of the included studies according to the Prisma Checklist (Moher et al. 2009). We are aware of additional literature on interventions to support transitional care of the elderly (Laugaland et al. 2012). To be included in the review, studies had to attend to patient participation in transitional care of elderly.

6 Conclusion

Our review shows that studies exploring elderly patients’ participation in transitional care are related to discharge planning. Results show that elderly patients often were excluded and not participating in discussions about discharge. When they were present they often felt not being seen or heard by professionals. In addition, they sometimes did not perceive participation relevant. Our review identifies several tools implemented to support patient participation in transitional care. Some tools were successfully implemented while others were not experienced by patients as enhancing their ability to influence on their situation. The studies in this review indicate that elderlies’ participation in decision-making and transitional care is typically quite poor, but can be supported by use of tools for example transition coaches, post-discharge follow-up, care plans, information and education of patients about self-management strategies and involvement of family and caregivers. Healthcare professionals need education and training to implement patient participation in a way that empowers patients. Patients and their families need to be made aware of and educated to use their rights to participate in decisions concerning their needs and care level. Healthcare professionals should facilitate transitional care practices setting the patient in the center of care, by listening to and supporting the patients, using common language to identify their needs. In this way, patient empowerment can be facilitated and enable elderly patients to take part in communication and decision-making in collaboration with healthcare professionals.

Notes

Several concepts are used in the review sample for tools. In this study tools is a collective term for concepts like measures, interventions, initiatives.

References

Aase K, Testad I (2010) First, second, one and a half—What about safety? Universitetsforlaget, Oslo

Almborg AH, Ulander K, Thulin A, Berg S (2008) Patients’ perceptions of their participation in discharge planning after acute stroke. J Clin Nurs 18:199–209

Attree M (2001) Patients’ and relatives’ experiences and perspectives of “Good” and “Not so Good” quality care. J Adv Nurs 33(4):456–466

Benten J, Spalding NJ (2008) Intermediate care: what are service users’ experiences of rehabilitation? Qual Aging 9(3):4–14

Brooks N (2002) Intermediate care rapid assessment support service: an evaluation. Br J Community Nurs 7(12):623–633

Bull MJ, Hansen HE, Gross CR (2000) A professional patient partnership model of discharge planing with elders hospitaluzed with heart failure. Appl Nurs Res 13(1):19–28

Cahill J (1996) Patient participation: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 24:561–571

Clarke A, Sohanpal R, Wilson G, Taylor S (2010) Patients’ perceptions of early supported discharge for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a qualitative study. Qual Saf Health Care 19:95–98. doi:10.1136/qshc.2007.025668

Coleman EA, Boult C (2003) Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. JAGS 51(4):556–557

Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Min S, Parry C, Kramer AM (2004) Preparing patients and caregivers to participate in care delivered across settings: the care transitions intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc 52(11):1817–1825

Coleman EA, Mahoney E, Parry C (2005) Assessing the quality of preparation for posthospital care from the patient’s perspective—the care transitions measure. Med Care 43(3):246–255. doi:10.1097/00005650-200503000-00007

Danielsen B, Fjær S (2010) Experiences with transferring sick elderly patients from hospital to municipality (in Norwegian). Forskning 4(1):28–34

Efraimsson E, Sandman PO, Hydén L, Rasmussen BH (2004) Discharge planning: ‘fooling ourselves’?—Patient participation in conferences. J Clin Nurs 13(5):562–570

Efraimsson E, Sandman PO, Rasmussen BH (2006) They were talking about me—elderly women’s experiences of taking part in a discharge planning conference. Scand J Caring Sci 20(1):68–78. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00382.x

Ekdahl AW, Andersson L, Friedrichsen M (2009) They do what they think is the best for me. Frail elderly patients’ preferences for participation in their care during hospitalization. Patient Educ Couns 80(2):233–240. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.026

Eldh A (2006) Patient participation-what it is and what it is not. Doctoral thesis. Örebro Studies in Caring Sciences, Örebro University, Department of Health Sciences, Örebro, Sweden

Ellis-Hill C, Robison J, Wiles R, McPherson K, Hyndman D, Ashburn A (2009) Going home to get on with life: patients and carers [sic] experiences of being discharged from hospital following a stroke. Disabil Rehabil 31(2):61–72. doi:10.1080/09638280701775289

Foss C, Askautrud M (2010) Measuring the participation of elderly patients in the discharge process from hospital: a critical review of existing instruments. Scand J Caring Sci 24:46–55

Foss C, Hofoss D (2011) Elderly persons` experiences of participation in hospital discharge process. Patient Educ Couns 85:68–73

Gibbon B (2004) Service user involvement: key contributors, goal setting and discharge home. JARNA 7(3):8–12

Godolphin W (2009) Shared decision-making. Healthc Q 12 (Special Issue)

Griffith J, Brosman M, Lacey K, Keeling S, Wilkinson T (2004) Family meetings—a qualitative exploration of improving care planning with older people and their families. Age Ageing 33(6):577–581. doi:10.1093/ageingafh198

Grimmer K, Moss J, Falco J, Kindness H (2006a) Incorporating patient and career concerns in discharge plans: the development of a practical patient-centred checklist. Internet J Allied Health Sci Pract 4(1):8p

Grimmer KA, Dryden LR, Puntumetakul R, Young AF, Guerin M, Deenadayalan Y, Moss JR (2006b) Incorporating patient concerns into discharge plans: evaluation of a patient-generated checklist. Internet J Allied Health Sci Pract 4(2):1–23

Hedberg B, Johanson M, Cederborg A (2008) Communicating stroke survivors’ health and further needs for support in care-planning meetings. J Clin Nurs 17(11):1481–1491. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02053.x

Huber DL, McClelland E (2003) Patient preferences and discharge planning transitions. J Prof Nurs 19(3):204–210

Huby G, Stewart J, Tierney A, Rogers W (2004) Planning older people’s discharge from acute hospital care: linking risk management and patient participation in decision-making. Health Risk Soc 6(2):115–132

Huby G, Brook JH, Thompson A, Tierney A (2007) Capturing the concealed: interprofessional practice and older patients’ participation in decision-making about discharge after acute hospitalization. J Interprof Care 21(1):55–67

Institute of Medicine (2001) Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system of the 21st century. Committee of Health Care in America. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

Jangland E, Carlsson M, Lundgren E, Gunningberg L (2012) The impact of an intervention to improve patient participation in a surgical care unit: a quasi-experimental study. Int J Nurs Stud 49(5):528–538. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.10.024

Laugaland K, Aase K, Barach P (2012) Interventions to improve patient safety in transitional care—a review of the evidence. Work 41:2915–2924. doi:10.3233/WOR-2012-0544-2915

McCall K, Keen J, Farrer K, Maguire R, McCann L, Johnston B (2008) Perceptions of the use of a remote monitoring system in patients receiving palliative care at home. Int J Palliat Nurs 14(9):426–431

McKain S, Henderson A, Kuys S, Drake S, Kerridge L, Ahern K (2005) J Clin Nurs 14:704–710

Merten H, Lubberding S, Wagtendonk I, Johannesma PC, Wagner C (2011) Patient safety in elderly hip fracture patients: design of a randomised controlled trial. Health Serv Res 11:59

Moats G (2007) Discharge decision-making, enabling occupations, and client-centred practice. Can J Occup Ther 74(2):91–101

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaf J, Altman DG; The PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(6):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

Parry C, Kramer H, Coleman E (2008) A qualitative exploration of a patient-centered coaching intervention to improve care transitions in chronically ill older adults. Home Health Care Serv Q 25(3–4):39–53. doi:10.1300/J027v25n0303

Perry MAC, Hudson S, Ardis K (2011) If I didn’t have anybody, what would I have done? Experiences of older adults and their discharge home after lower limb orthopaedic surgery. J Rehabil Med 43:916–922

Polit DF, Beck CT (2008) Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice, 8th edn. Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Preen DB, Bailey BES, Wright A, Kendall P, Philips M, Hung J, Hendriks R, Mather A, Williams E (2005) Effects of a multidisciplinary, post-discharge continuance of care intervention on quality of life, discharge satisfaction, an hospital length of stay: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Qual Health Care 17(1):43–51

Reed J, Stanley D (2003) Improving communication between hospitals and care homes: the development of a daily living plan for older people. Health Soc Care Community 11(4):356–363

Roberts K (2001) Across the health-social care divide: elderly people as active users of health care and social care. Health Soc Care Community 9(2):100–107

Roberts K (2002) Exploring participation: older people on discharge from hospital. J Adv Nurs 40(4):413–420

Rydeman I, Törnkvist L (2009) Getting prepared for life at home in the discharge process—from the perspective of the older persons and their relatives. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford

Somme D, Thomas H, de Stampa M, Lahjibi-Paulet H, Saint-Jean O (2008) Residents’ involvement in the admission process in long-term care settings in France: results of the “EHPA 2000” survey. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 47(2):163–172

Storm M, Edwards A (2012) Models of user involvement in the mental health context: intentions and implementation challenges. Psychiatr Q. doi:10.1007/s11126-012-9247-x

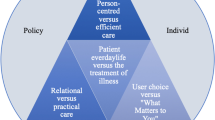

Storm M, Dyrstad DN, Aase K (2012) A review of patient-oriented care models as applied in transitional care of the elderly. Poster presented at the 2nd Nordic conference on research in patient safety and quality in healthcare, Copenhagen, Denmark. http://www.nsqh.org/2012/Abstracts

Swinkels A, Mitchell T (2008) Delayed transfer from hospital to community settings: the older person’s perspective. Health Soc Care Community 17(1):45–53

Tang P, Venables T (2000) Smart homes and telecare for independent living. J Telemed Telecare 6(1):8–14

Thompson AGH (2007) The meaning of patient involvement and participation: a taxonomy. Open University Press, Maidenhead

Watkins L, Hall C, Kring D (2012) Hospital to home. Prof Case Manag 17(3). doi:10.1097/NCM.0b013e318243d6a7

Weingart SN, Zhu J, Chiapetta L, Stuver SO, Schneider EC, Epstein AM et al (2011) Hospitalized patients’ participation and its impact on quality of care and patient safety. Int J Qual Health Care 23(3):269–277

Wetzels R, Harmsen M, Van Weel C, Grol R, Wensing M (2008) Interventions for improving older patients’ involvement in primary care episodes (review). Cochrane Collab 4:1–29

Whittemore R, Knafl K, Gray EN (2005) The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs 52(5):546–553

WHO (2011a) Ageing and life course. Cited 2011 June 25. http://www.who.int/ageing/en/index.html

WHO (2011b) Patient safety. Cited 2011 March 20. http://www.who.int/patientsafety/patients_for_patient/statement/en/index.html

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Dyrstad, D.N., Testad, I., Aase, K. et al. A review of the literature on patient participation in transitions of the elderly. Cogn Tech Work 17, 15–34 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10111-014-0300-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10111-014-0300-4