Abstract

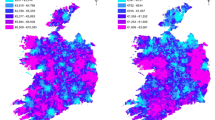

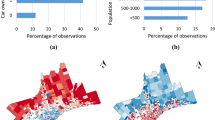

Core and peripheral contrasts in journey-to-work trip length can be interpreted as imputing the relative value of origin and destination accessibility (yielding theoretical proxies for rent and wages). Because the main variables are shown to be critically dependent on spatial structure, they may be interpreted as showing the shadow prices due to comparative location. There is also a unifying connection between these results and the existing literature on many dimensions: rent gradients, accessibility, and emissivity. In an empirical example, the advantages of a panoramic view of national commuting statistics are shown, using an Irish data set. Variations in the rates of participation in trip making by location, occupation, and gender are examined. Places that emit more trips than would be expected from their relative location are identified. Further, examining ways in which such emissivity is sensitive to a change in trip length highlights the regions where trips could possibly be adjusted to produce a shorter average trip length or which might be especially sensitive to reduction in employment. A careful reinterpretation of one of the key outputs from a calibrated spatial interaction model is shown to be consistent with the declining rent gradient expected from Alonso’s theory of land use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the case of the POWCAR data, imagine several hundred origin communities (towns) and the main destination aggregations being the 34 county level jurisdictions. The external zones are in fact special cases of the destinations—overseas, in multiple workplaces, at home, or without a clear indication on the data of the actual work place. Locations of towns and counties are simply determined from the centroids of the points with these ID values.

There are analogous measures on the destination side but these are omitted in the interests of concise results.

References

Alonso W (1964) Location and land use: toward a general theory of land rent. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Buliung RN, Kanaroglou PS (2002) Commute minimization in the Greater Toronto Area: applying a modified excess commute. J Transp Geogr 10(3):177–186

Cubukgil A, Miller EJ (1982) Occupational status and the journey-to-work. Transportation 11(3):251–276

Evans SP (1973) A relationship between the gravity model for trip distribution and the transportation problem in linear programming. Transp Res 7(1):39–61

Fan Y, Khattak A, Rodriguez D (2011) Household excess travel and neighbourhood characteristics: associations and trade-offs. Urban Stud 48(6):1235–1253

Giuliano G, Small KA (1993) Is the journey to work explained by urban structure? Urban Stud 30(9):1485–1500

Grigg TJ (1984) Probabilistic versions of the short-run Herbert-Stevens model. Environ Plann A 16(6):715–732

Hamilton B (1982) Wasteful commuting. J Political Econ 90(5):1035–1053

Hamilton B (1989) Wasteful commuting again. J Political Econ 97(6):1497–1504

Handy S, Weston L, Mokhtarian PL (2005) Driving by choice or necessity? Transp Res Part A Policy Pract 39(2–3):183–203

Hanson S, Johnston I (1985) Gender differences in work-trip length: explanations and implications. Urban Geogr 6(3):193–219

Herbert JD, Stevens BH (1960) A model for the distribution of residential activity in urban areas. J Reg Sci 2(2):21–36

Hincks S, Wong C (2010) The spatial interaction of housing and labour markets: commuting flow analysis of North West England. Urban Stud 47(3):620–649

Horner MW (2002) Extensions to the concept of excess commuting. Environ Plann A 34(3):543–566

Horton FE, Wittick RI (1969) A spatial model for examining the journey-to-work in a planning context. Prof Geogr 21(4):223–226

Irish Times (2003) Driving me crazy series on commuting counties April 26–May 8

Kawabata M (2009) Spatiotemporal dimensions of modal accessibility disparity in Boston and San Francisco. Environ Plann A 41(1):183–198

Lang RE (2003) Edgeless cities: examining the noncentered metropolis. Brookings Institution Press, Washington

Lin J–J, Yang A-T (2009) Structural analysis of how urban form impacts travel demand: evidence from Taipei. Urban Stud 46(9):1951–1967

Lyons G, Chatterjee K (2008) A human perspective on the daily commute: costs benefits and trade-offs. Transp Rev 28(2):181–198

Ma K-R, Banister D (2006) Excess commuting: a critical review. Transp Rev 26(6):749–767

Marion B, Horner M (2007) Comparison of socioeconomic and demographic profiles of extreme commuters in several US metropolitan statistical areas. Transp Res Rec 2013:38–45

Melo Patricia C, Graham DJ, Noland RB (2011) The effect of labour market spatial structure on commuting in England and Wales. J Econ Geogr. doi:101093/jeg/lbr011. First published online: June 6 2011

Mokhtarian PL et al (2004) Telecommuting residential location and commute-distance traveled: evidence from state of California employees. Environ Plann A 36(10):1877–1897

Morgenroth ELW (2002) Commuting in Ireland: an analysis of inter-county commuting flows. Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin

Murphy E, Killen JE (2011) Commuting economy an alternative approach for assessing regional. Commut Effic Urban Stud 48(6):1255–1272

O’Kelly ME (2010) Entropy-based spatial interaction models for trip distribution. Geograp Anal 42(4):472–487

O’Kelly ME, Niedzielski MA (2009) Are long commute distances inefficient and disorderly? Environ Plann A 41(11):2741–2759

Osland L (2010) Spatial variation in job accessibility and gender: an intraregional analysis using hedonic house-price estimation. Environ Plann A 42(9):2220–2237

Sang S, O’Kelly M, Kwan M-P (2011) Examining commuting patterns: results from a journey-to-work model disaggregated by gender and occupation. Urban Stud 48(5):891–905

Senior ML, Wilson AG (1974) Explorations and syntheses of linear programming and spatial interaction models of residential location. Geograp Anal 6(3):209–238

Shearmur R (2006) Travel from home: an economic geography of commuting distances in montreal. Urban Geograp 27(4):330–359

Simpson W (1987) Workplace location, residential location, and urban commuting. Urban Stud 24(2):119–128

Stabler JC et al (1996) Spatial labor markets and the rural labor force. Growth Change 27(2):206–230

Watts MJ (2009) The impact of spatial imbalance and socioeconomic characteristics on average distance commuted in the Sydney metropolitan area. Urban Stud 46(2):317–339

Webber MJ (1980) A theoretical analysis of aggregation in spatial interaction models. Geograp Anal 12(2):129–141

Wheaton WC (1974) Linear programming and locational equilibrium: the Herbert-Stevens model revisited. J Urban Econ 1(3):278–287

Wilson AG (1974) Urban and regional models in geography and planning. Wiley, London

Acknowledgments

Paper presented at the AAG, Washington DC 2010. Thanks to NIRSA for travel support to Maynooth and for data tables. We are very pleased to acknowledge an especially detailed data set (the POWCAR Place of Work Data) provided courtesy of Central Statistics Office, Ireland. Rob Kitchin, NIRSA, NUI Maynooth, Ireland provided comments and support for this research. The referees’ comments are acknowledged with thanks.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Sensitivity analysis

Appendix: Sensitivity analysis

Connecting the model notation:

Differentiating the second and third expressions with respect to β k

Recognizing that \( T_{ijk} = \exp (\lambda_{ik} + \mu_{jk} - \beta_{k} C_{ij} ) \) and after rearranging:

Given that \( O_{ik} = \sum\nolimits_{j} {T_{ijk} } , \) we can restate as:

which gives the key result for the interpretation of the sign of the origin effects shown in the maps:

Similarly, in the case of destinations, connecting the model notation:

Differentiating the second and third expressions with respect to β k

Rearranging as before:

Given that \( D_{jk} = \sum\nolimits_{i} {T_{ijk} } , \) we can restate as:

which gives the key result for the interpretation of the sign of the destination effects:

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O’Kelly, M.E., Niedzielski, M.A. & Gleeson, J. Spatial interaction models from Irish commuting data: variations in trip length by occupation and gender. J Geogr Syst 14, 357–387 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10109-011-0159-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10109-011-0159-3