Abstract

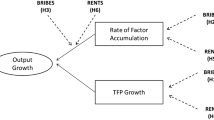

This article investigates the effects of corruption on the performance of the manufacturing sector at the state level in India. We employ conviction rates of corruption-related cases as an instrument for the extent of corruption, address the underreporting problem, and examine the impact of corruption on the gross value added per worker, total factor productivity, and capital-labor ratio of three-digit manufacturing industries in each state. Our estimation results show that corruption reduces gross value added per worker and total factor productivity. Furthermore, we show that the adverse effects of corruption are more salient in industries with smaller average firm size.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Some earlier studies claim that corruption has some desirable effects, namely, that corruption could speed up bureaucratic processes which would otherwise be very slow (see, e.g., Leff 1964; Leys 1970; Lui 1985). Such arguments have been refuted by many scholars (e.g., Kaufmann 1997), and have not been supported by later empirical studies. However, some recent studies show that in countries with inefficient bureaucracies, corruption offsets the negative effects of entry regulation or has positive effects on entry of firms (Klapper et al. 2006; Dreher and Gassebner 2008).

Other factors discussed in the literature include the following. Corruption lowers inward foreign direct investment, and shifts ownership structures toward joint ventures (Wei 2000; Smarzynska and Wei 2000). Corruption is also shown to increase income inequality (e.g., Gupta et al. 2002), inflation rate (e.g., Al-Marhubi 2000), political instability (e.g., Mo 2001), restrictions on capital flows (e.g., Dreher and Siemers 2009), and aid flows (e.g., Alesina and Weder 2002).

However, Rock and Bonnett (2004) show that in large East Asian countries, higher corruption is correlated with higher economic growth rates. On the basis of a detailed study of South Korea and the Philippines, Kang (2002) proposed a different theoretical framework for the determinant of corruption, in which the extent of corruption is determined by the balance of power between political and business elites. While the weakening of political elites may increase corruption if business elites are strong, it may decrease corruption if business elites are also weak.

The most recent studies on the consequences of corruption examine the conditions under which corruption exerts any influence on outcomes. Among others, De la Croix and Delavallade (2009) show that in developing countries with high predatory technology, corruption tends to lower public expenditures on education and health. Meon and Sekkat (2005) show that corruption lowers economic growth and investment in only countries with a lower level of governance in terms of rule of law and government effectiveness. Haque and Kneller (2009) theoretically show that there exist thresholds in GDP per capita wherein the relationship between corruption and economic development differs, and present some empirical findings of such thresholds.

Hall and Jones (1999) consider two elements in constructing the measure of social infrastructure. The first element includes five subelements, one of which is corruption. The other four subelements are law and order, bureaucratic quality, risk of expropriation, and government repudiation of contracts.

Wyatt (2002) also confirms that the measure of corruption in the governance indicators of Kaufmann et al. (1999) significantly affects GDP per capita, while they also show that the measures of government effectiveness and rule of law in their governance indicators significantly influence the extent of corruption.

Because of the endogeneity problem, Lambsdorff (2003) chooses the ratio of GDP to capital stock as a dependent variable, which suffers less from endogeneity, and shows that corruption reduces the ratio.

In response to this situation, an innovative study by Dreher et al. (2007) estimates a structural equation model with corruption as a latent variable in order to obtain a new index of corruption. Olken (2006) more directly calculates the extent of corruption by using accounting data on road projects and survey data on necessary costs for implementing these projects in Indonesian villages.

Another index that has been often used in the literature is the index for control of corruption in World Governance Indicators. The index designates the position of a country on the hypothetical normal distribution with respect to control of corruption among all the sample countries. Thus, a change in the position of a country over time reflects the relative change of the country’s position, but does not capture any meaningful cardinal change in the extent of corruption control.

All these articles use the conviction data for US States.

Although limiting the sample to India makes it difficult to generalize the estimation results to other countries, it would provide a useful robustness check for previous cross-national studies.

Although their primary concern is not with corruption, Aghion et al. (2008) show that in India after the deregulation of three-digit industries, firms invested more in the states where labor regulation was more pro-employer.

Questions under 11.3 and 11.5 in the FACS questionnaire are closely related to corruption. See CII and the World Bank (2008) at http://microdata.worldbank.org/enterprise/index.php/ddibrowser/279/download/1617.

Moreover, the studies conducted by Transparency International India (2005, 2008) show a huge variety of corruption not only among states but also across different kinds of public services. They have shown that among nine public services, the police and the judiciary are perceived by the public to be the most corrupt.

If corruption raises the capital-labor ratio so much that it overwhelms the effect of corruption on total factor productivity, it would be possible that gross value added, which is the weighted sum of total factor productivity and capital labor ratio, may increase.

It would be preferable to have a dummy variable capturing the combination of \(s\) and three-digit manufacturing industry \(i\), but the computational cost of an estimation including such a large number of dummy variables, namely, one dummy variable for each combination of state and three-digit manufacturing industry, is not practical on our personal computers. Thus, we settled upon dummies for the combination of two-digit industry \(j\) and state \(s\).

Instrumental variable estimation also solves the problem of omitted variable.

GDP per capita in constant 2,000 US dollars is obtained as follows. First, GDP per capita is expressed in 2,000 local currency value using the series of price index in local currency. GDP per capita in constant 2,000 local currency is then converted to current 2,000 US dollars using 2,000 official exchange rate.

Developing country dummy is set to 1 for Argentina*, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Cambodia, Colombia*, Costa Rica, India, Indonesia, Mozambique, Nigeria, Panama, Paraguay, Philippines*, South Africa, Uganda*, and Zimbabwe among sample countries. The rest of the countries included in the sample are Albania*, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belgium, Belarus*, Bulgaria*, Canada*, Croatia*, Czech Republic*, Denmark, Finland, France*, Georgia*, Hungary*, Japan, Republic of Korea, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia*, Lithuania*, Macedonia, Malta, Mongolia*, Netherlands*, Philippines, Poland*, Portugal, Romania*, Russia*, Slovakia, Slovenia*, Sweden*, Switzerland, Ukraine*, and United States*. Starred countries appear twice in the data set in different survey years. Transition countries are not included in the developing country group.

For UK, we add Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, and England.

Note that due to the availability of the data on each dependent variable, the number of observations varies among the dependent variables, and first-stage estimation results differ. However, the results including specification tests are almost the same across our estimations. Thus, we omit the results of our first stage estimation for other estimations in Tables 6 and 7. The results are available upon request.

We omitted the first-stage estimation results due to space constraints. The first stage estimation results including various specification tests are reasonable. The results are available upon request.

References

Abramo WC (2005) How far do perceptions go? Working paper. Transparency Brazil

Acemoglu D, Verdier T (1998) Property rights, corruption and the allocation of talent: a general equilibrium approach. Econ J 108:1381–1403

Acemoglu D, Verdier T (2000) The choice between market failures and corruption. Am Econ Rev 90(1):194–211

Ades A, Di Tella R (1997) National champions and corruption: some unpleasant interventionist arithmetic. Econ J 107:1023–1042

Aghion P, Burgess R, Redding SJ, Zilibotti F (2008) The unequal effects of liberalization: evidence from dismantling the License Raj in India. Am Econ Rev 98:1397–1412

Aidt TS (2003) Economic analysis of corruption: a survey. Econ J 113:632–652

Alesina A, Weder B (2002) Do corrupt governments receive less foreign aid? Am Econ Rev 92(4):1126–1137

Al-Marhubi H (2000) Corruption and inflation. Econ Lett 66(2):199–202

Andvig JC (2005) A house of straw, sticks or bricks? Some notes on corruption empirics. Paper presented at the IV global forum on fighting corruption and safeguarding integrity, session measuring integrity, June 7 2005

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: monte carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58(2): 277–297

Bertrand M, Djankov S, Hanna R, Mullainathan S (2007) Obtaining a driver’s License in India: an experimental approach to studying corruption. Q J Econ 122(4):1639–1676

Brunetti A, Kisunko G, Weder B (1998) Credibility of rules and economic growth: evidence from a worldwide private sector survey. World Bank Econ Rev 12(3):353–384

Brunetti A, Weder B (1998) Investment and institutional uncertainty: a comparative study of different uncertainty measures. Weltwirtschaftliches Archic 134(3):513–533

Campos JE, Lien D, Pradhan S (1999) The impact of corruption on investments: predictability matters. World Dev 27(6):1059–1067

De la Croix D, Delavallade C (2009) Growth, public investment and corruption with failing institutions. Econ Gov 10:187–219

Debroy B, Bhandari L (2005) Economic freedom for states of India. Rajiv Gandhi Institute for Contemporary Studies, India

Delavallade C (2006) Corruption and distribution of public spending in developing countries. J Econ Finance 30(3):222–239

Dreher A, Herzfeld T (2005) The economic costs of corruption: a survey and new evidence. ETH Zurich, Mimeo

Dreher A, Kotsogiannis C, McCorrison S (2007) Corruption around the world: evidence from a structural model. J Comp Econ 35(3):443–446

Dreher A, Siemers L-HR (2009) The nexus between corruption and capital account restrictions. Public Choice 140:245–265

Dreher A, Gassebner M (2008) Greasing the wheels of entrepreneurship? The impact of regulations and corruption on firm entry. CESifo working paper series no. 2013. CESifo Group, Munich

Ehlrich I, Lui FT (1999) Bureaucratic corruption and endogenous growth. J Polit Econ 107(6):270–293

Gardiner J (2002, 1993) Defining corruption. In: Johnston M, Heidenheimer M (eds) Political corruption: concepts and contexts, 3rd edn. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, New Jersey

Glaeser ED, Saks RE (2006) Corruption in America. J Public Econ 90:1053–1072

Goel RK, Rich DP (1989) On the economic Incentives for taking bribes. Public Choice 61:269–275

Goel RK, Nelson MA (1998) Corruption and government size: a disaggregated analysis. Public Choice 97:107–120

Gupta S, De Mello L, Sharan R (2001) Corruption and military spending. Eur J Polit Econ 17(4):749–777

Gupta S, Davoodi HR, Alonso-Terme R (2002) Does corruption affect income inequality and poverty? In: Abed GT, Gupta S (eds) Governance, corruption, and economic performance. International Monetary Fund, Publication Services, Washington, pp 458–486

Gupta S, Davoodi HR, Tiongson ER (2002) Corruption and the provision of health care and education services. In: Abed GT, Gupta S (eds) Governance, corruption, and economic performance. International Monetary Fund, Publication Services, Washington, pp 254–279

Gymiah-Brempong K (2002) Corruption, economic growth, and income inequality in Africa. Econ Gov 3:183–209

Hall RE, Jones CI (1999) Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others? Q J Econ 114:83–116

Haque ME, Kneller R (2009) Corruption clubs: endogenous thresholds in corruption and development. Econ Gov 10:345–373

Jain AK (2001) Corruption: a review. J Econ Surv 15(1):71–121

Johnson S, Kaufmann D, Shleifer A (1997) The unofficial economy in transition. Brook Papers Econ Activity 27(2):159–239

Johnson S, Kaufmann D, Zoido-Lobaton P (1998) Regulatory discretion and the unofficial economy. Am Econ Rev 88:387–392

Kang DC (2002) Crony capitalism. Cambridge University Press, New York

Kaufmann D (1997) Corruption: the facts. Foreign Policy summer 1997, pp 114–131

Kaufmann D, Kraay A, Mastruzzi M (2008) Governance matters VII: aggregate and individual governance indicators 1996–2007. World Bank policy research working paper no. 4654. Washington, DC

Kaufmann D, Kraay A, Zoido-Lobaton P (1999) Governance Matters. World Bank policy research working paper no. 2196. Washington, DC

Klapper L, Laeven L, Rajan R (2006) Entry regulation as a barrier to entrepreneurship. J Financ Econ 82:591–629

Kleibergen F, Paap R (2006) Generalized reduced rank tests using the singular value composition. J Econ 133:97–126

Krueger AO (1974) The political economy of the rent-seeking society. Am Econ Rev 64:291–303

Lambsdorff JG (2003) How corruption affects productivity. Kyklos 56:457–474

Lambsdorff JG (2006) Causes and consequences of corruption: what do we know from a cross-section of countries? In: Rose-Ackerman S (ed) International handbook on the economics of corruption. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 3–51

Leff NH (1964) Economic development through bureaucratic corruption. In: Heidenheimer AJ (ed) Political corruption: readings in comparative analysis. Holt Renehart, New York, pp 8–14

Levinsohn J, Petrin A (2003) Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. Rev Econ Stud 70(2):317–342

Leys C (1970) What is the problem about corruption? In: Heidenheimer AJ (ed) Political corruption: readings in comparative analysis. Holt Renehart, New York, pp 31–37

Lui F (1985) An equilibrium queuing model of corruption. J Polit Econ 93:760–781

Marenin O (1997) Victimization surveys and the accuracy and reliability of official crime data in developing countries. J Crim Justice 25(6):463–475

Mauro P (1995) Corruption and growth. Q J Econ 110(3):681–712

Mauro P (1997) The effects of corruption on growth, investment, and government expenditure: a cross-country analysis. In: Elliot KA (ed) Corruption and the global economy. Institute for International Economics, Washington, DC

Mauro P (1998) Corruption and the composition of government expenditure. J Public Econ 69(2):263–279

Meon P-G, Sekkat K (2005) Does corruption grease or sand the wheels of growth? Public Choice 122(1/2):69–97

Mo PH (2001) Corruption and economic growth. J Comp Econ 29(1):66–79

Mocan N (2004) What determines corruption? International evidence from micro data. NBERw working paper no. 10460

Olken BA (2006) Corruption and the costs of redistribution: micro evidence from Indonesia. J Public Econ 90:853–870

Olken BA (2009) Corruption perceptions vs. corruption reality. J Public Econ 98(7–8):950–964

Pellegrini L, Gerlagh R (2004) Corruption’s effect on growth and its transmission channels. Kyklos 57(3):429–456

Philip M (1997) Defining political corruption. Polit Stud 45:436–462

Ray D (1998) Development economics. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Razafindrakoto M, Routboud F (2006) Are international databases on corruption reliable? A comparison of expert opinion surveys and household surveys in sub-Saharan Africa. Document de travail DT/2006-17. DIAL, Paris School of Economics

Rock MT, Bonnett H (2004) The comparative politics of corruption: accounting for the East Asian paradox in empirical studies of corruption, growth and investment. World Dev 32(6):999–1017

Rose-Ackerman S (1978) Corruption: a study in political economy. Academic Press, New York

Shleifer A, Vishny W (1993) Corruption. Q J Econ 108(3):599–617

Smarzynska B, Wei S-J (2000) Corruption and composition of foreign direct investment: firm level evidence. National Bureau of Economic Research, NBER working paper no. 7969

Soares RR (2004) Development, crime, and punishment: accounting for the international differences in crime rates. J Dev Econ 73:155–184

Stock JH, Yogo M (2001) Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. Unpublished manuscript, Harvard University

Svensson J (2005) Eight questions about corruption. J Econ Perspect 19:19–42

Tanzi V, Davoodi H (2002a) Corruption, public investment, and growth. In: Abed GT, Gupta S (eds) Governance, corruption, and economic performance. International Monetary Fund, Publication Services, Washington, DC, pp 280–299

Tanzi V, Davoodi H (2002b) Corruption, growth, and public finances. In: Abed GT, Gupta S (eds) Governance, corruption, and economic performance. International Monetary Fund, Publication Services, Washington, DC, pp 197–222

Tanzi V, Davoodi H (1997) Corruption, public investment, and growth. International monetary fund working paper no. WP/97/139

Transparency International (2002) Corruption in South Asia. http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/apcity/unpan019883.pdf

Transparency International India (2005) India corruption study 2005

Transparency International India (2008) India corruption study 2008 with focus on BPL households

Veeramani C, Goldar BN (2005) Manufacturing productivity in Indian states: does investment climate matter? Econ Polit Wkly 40(24):2413–2420

Wei S-J (2000) How taxing is corruption on international investors? Rev Econ Stat 82(1):1–11

Welsch H (2004) Corruption, growth, and the environment: a cross-country analysis. Environ Dev Econ 9(5):663–693

World Bank (2008) Doing business 2008. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Wyatt G (2002) Corruption, productivity and transition. CERT discussion papers no. 205. Centre for Economic Reform and Transformation, Heriot Watt University

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Data sources and construction of variables

Appendix: Data sources and construction of variables

1.1 Gross value added per worker

First, we obtain real gross value added by dividing the gross value added of each three-digit manufacturing industry in each year and state, available in the Annual Survey of Industries, by the deflator for the value of gross output at the two-digit industry level. We then divide the real gross value added by the number of workers in the three-digit manufacturing industries.

1.2 Capital-labor ratio

Capital stock is obtained by dividing fixed capital in the Annual Survey of Industries by the implicit capital deflator used in the National Accounts Statistics, published by the Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India. We then divide the capital stock by the number of workers in the three-digit manufacturing industries.

1.3 TFP

The TFP index is obtained by the method described in the main body.

1.4 Corruption

The data on corruption in each state is derived from Crime in India, published annually by the Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. The number of registered cases of corruption-related cases corresponds to “cases registered during that year” in the table for “statement of cognizable crimes registered and their disposal by anti-corruption and vigilance departments of states and UTs under the Prevention of Corruption Act and related sections of IPC during (that year)”. We obtain the variable corruption by the method described in Sects. 2–4.

1.5 Conviction rate

To obtain the conviction rate, we divide “cases convicted” by “total cases for investigation” in Crime in India mentioned above.

1.6 Electricity

Electricity sales (million kWh) to ultimate consumers are obtained from the CMIE publication, Infrastructure. This number is divided by the population in thousands.

1.7 Road

Data on total road length is available from Basic Road Statistics of India, Ministry of Shipping, Road Transport and Highways, Government of India. This number is divided by the population in thousands.

1.8 School enrollment rates

Both primary school and secondary school enrollment rates are available from Selected Educational Statistics, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India. We use the enrollment ratio for grades 1 through 5 as primary school data.

1.9 Disputes per worker

Statewise numbers of industrial disputes are derived from the Indian Labour Yearbook, annually published by the Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, Government of India.

1.10 Bank branches

The data on the number of branches of scheduled commercial banks is obtained from Statistical Tables Relating to Banks in India, published by the Reserve Bank of India. The number of offices is divided by the population in thousand.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kato, A., Sato, T. The effect of corruption on the manufacturing sector in India. Econ Gov 15, 155–178 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-014-0140-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-014-0140-y