Abstract

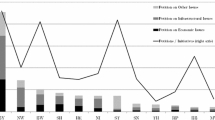

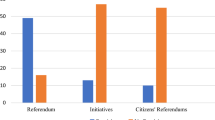

This study contains further evidence on the economic effects of direct democratic institutions. A first study found that countries with national initiatives have higher government expenditure and are characterized by more rent-seeking activity, that the effects of direct democratic institutions become stronger if the frequency of their actual use is taken into account, and that effects are stronger in countries with weak democracies. This study sheds more light on these findings by drawing on a new dataset covering more countries and incorporating more institutional detail. The results of the earlier study are largely confirmed: mandatory referendums lower government expenditure and improve government efficiency, initiatives have the opposite effects. The incorporation of more institutional detail into the analysis shows that the increase in government expenditures connected with initiatives is primarily driven by citizen, as opposed to agenda, initiatives. Further, referendums held at both the constitutional and post-constitutional levels are correlated with larger debt. Finally, neither the possibility of a recall nor the degree to which referendum results are binding significantly affect our dependent variables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Hug (2005) can be considered as a forerunner in analyzing the effects of direct democracy on a cross country level. For a cross-section of 15 transition countries in Central and Eastern Europe, he finds that direct democratic institutions cannot explain variation in the confidence of various organizations such as government, parliament, the EU or the armed forces.

See Hug (2004) for the pertinent theoretical arguments.

Note that the two kinds of referendums are not mutually exclusive: a country might use MANREF for a select number of policy issues and allow OPREF for the rest.

Twenty-six countries are coded 1 in all three dummy variables: Albania, Armenia, Belarus, Bolivia, Brazil, Croatia, Ecuador, Estonia, France, Guatemala, Italy, the Kyrgyz Republic, Panama, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovenia, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, Uganda, Ukraine, Uruguay, and Venezuela. 19 countries have initiative rights and in 21, mandatory referendums are provided for by law.

But see Gerber et al. (2004) who name numerous examples for cases in which initiative results remained unimplemented by politicians.

The possibility of a recall could change the character of both the presidential and the parliamentary form of government. It has been argued that presidential systems have a higher degree of separation of powers than parliamentary ones as the president does not depend on a parliamentary majority for his or her survival in office. In a presidential system with recall, the president depends on the absence of a recall or-should it actually take place-on being confirmed by recall. This means that the president’s survival depends on the absence of opposition by his or her constituents. In parliamentary systems with the institution of recall, the head of the executive is even more vulnerable than in parliamentary systems without it because the executive’s survival depends on the absence of opposition in both the legislature and the constituency at large.

Compared to our previous study, IDEA’s coding is quite liberal: based on the same set of countries, we previously only coded 40 % of the countries as having mandatory referendums (here, 55 % ), 20 % as having optional referendums (here, 75 % !), and 20 % (here, 35 %) as having initiatives. All differences are substantial, but the one for regarding optional referendums is a sure standout.

Which means that the variables LEVEL, BINDINGNESS and ISSUES are all coded 1.

Given that Persson and Tabellini (2003) find that both the form of government (PRES) as well as the electoral systems (MAJ) have significant effects on a number of dependent variables, a referee suggested that we systematically include them in our models. Implementation of this suggestion shows that the PRES coefficient is never significant according to conventional levels and MAJ only once, namely with regard to budget surplus. These results cast further doubt on the robustness of the results attained by Persson and Tabellini (for a more detailed critique, see Blume et al. 2009b).

Ex ante it is unclear whether the fiscal preferences of the median voter are more or less conservative than those of government. During the first half of the twentieth century, voters in the US initiative states were frequently fiscally less conservative than their elected representatives (Matsusaka 2000).

Matsusaka (2005: 197) succinctly states the problem: “A difficulty in developing instruments is that we do not yet understand why certain states adopted the process and others did not.”

The TSLS-estimates as well as the OLS estimates containing the coefficients of all included variables are available from the authors upon request. The first stage variables in the TSLS-estimates are exactly the same as those used for the Hausman tests as spelled out in the explanatory notes below the Tables containing the OLS estimates.

Then again—foreshadowing results reported later in the paper—we find no significant correlation between initiatives and perceived levels of rent seeking.

We did control for ideological orientation of governments but these results are not part of the Tables. The coefficient has the expected sign (leftist governments are correlated with higher social and welfare spending) and the result is significant at the 1 % level.

References

Banks (2004) Cross-national time-series data archive, 1815–2003 [electronic resource]. Databanks International, Binghamton

Beck Th, Clarke G, Groff A, Keefer Ph, Walsh P (2000) New tools and new tests in comparative political economy: the database of political institutions. The World Bank, Washington

Blume L, Müller J, Voigt S (2009a) The economic effects of direct democracy—a first global assessment. Pub Choice 140:431–461

Blume L, Müller J, Voigt S, Wolf C (2009b) The economic effects of constitutions: replicating—and extending—Persson and Tabellini. Pub Choice 139:197–225

Feld L, Matsusaka J (2003) Budget referendums and government spending: evidence from Swiss cantons. J Pub Econ 87:2703–2724

Fiorino N, Ricciuti R (2007) Determinants of direct democracy. CESifo Working Papers No. 2035

Freedom House (2000) Press Freedom Survey 2000, downloadable from: http://freedomhouse.org/pfs2000/method.html

Gerber E, Lupia A, Mccubbins M (2004) When does government limit the impact of voter initiatives? The politics of implementation and enforcement. J Polit 66(1):43–68

Heritage Foundation (2004) Index of Economic Freedom, downloadable from http://www.heritage.org/research/features/index/

Hug S (2004) Occurrence and policy consequences of referendums—a theoretical model and empirical evidence. J Theor Polit 16(3):321–356

Hug S (2005) The political effects of referendums: an analysis of institutional innovations in Eastern and Central Europe. Communist Post-Communist Stud 38:475–499

Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (2008) Direct Democracy—The International IDEA Handbook. Stockholm

Kaufmann D, Kraay A, Mastruzzi M (2003) Governance matters III: governance indicators for 1996–2002. World Bank Policy Research Department Working Paper

Matsusaka J (2000) Fiscal effects of the voter initiative in the first half of the twentieth century. J Law Econ 43:619–650

Matsusaka J (2005) Direct democracy works. J of Econ Perspect 19(2):185–206

Mueller D (2003) Public choice III. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Persson T, Tabellini G (2003) The economic effects of constitutions: what do the data say?. MIT Press, Cambridge

Roubini N, Sachs J (1989) Political and economic determinants of budget deficits in the industrial democracies. Eur Econ Rev 33:903–938

Whytock C (2007) Taking causality seriously in comparative constitutional law: insights from comparative politics and comparative political economy. Loyola Los Angeles Law Rev 41:629

World Values Study Group (2005/2006) World Values Survey 1981–1984, 1990–1993, 1995–1997, and 1999–2001. Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, Ann Arbor

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anne van Aaken, Matthias Dauner, Thomas Eger, Gabor Gottlieb, Sönke Haeseler, Felix Horbach, Sina Imhof, and Katharina Stepping as well as Amihai Glazer and two anonymous referees from this journal for constructive critique.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Many variables used in this paper are based on Persson and Tabellini (2003, PT) and (Blume et al. (2009a, b), BMVW).

AFRICA: |

Regional dummy variable, equal to 1 if a country is in Africa, 0 otherwise; source: PT |

AGE: |

Age of democracy defined as AGE = (2000–DEM_AGE)/200, with values varying between 0 and 1; sources: PT and BMVW |

AGE_CONST: |

Year in which the current constitution was passed; source: BMVW and the sources cited therein |

ASIAE: |

Regional dummy variable, equal to 1 if a country is in East Asia, 0 otherwise; source: PT |

AVELF: |

Index of ethno-linguistic fractionalization, ranging from 0 (homogeneous) to 1 (strongly fractionalized) averaging five sources; sources: PT and BMVW |

CATHO80: |

Percentage of a country’s population belonging to the Roman Catholic religion in 1980 (younger states are counted based on their average from 1990 to 1995); source: PT |

COL_ESPA: |

Spanish colonial origin, discounted by the number of years since independence (T_INDEP) and defined as COL_ESPA = COL_ESP * (250–T_INDEP)/250 |

COL_OTHA: |

Defined as COL_OTHA = COL_OTH * (250–T_INDEP)/250; see also COL_ESPA |

COL_UKA: |

Defined as COL_UKA = COL_UK * (250–T_INDEP)/250; see also COL_ESPA |

COMMLO: |

Dummy for common law legal origin, coded 1 if legal origin is common law; 0 if legal origin is any other |

CONFU: |

Dummy variable fort he religious tradition in a country, equal to 1 if the majority of the country’s population is Confucian/Buddhist/Zen, 0 otherwise; source: PT |

DE_FACTO_JI: |

Factual independence of the judiciary; values between 0 and 1 with 1 signaling a high level of factual independence; source: BMVW |

DEM_AGE: |

First year of democratic rule in a country, corresponding to the first year of a string of positive yearly values of the variable POLITY for that country that continues uninterrupted until the end of the sample, given that the country was also an independent nation during the entire period. Does not count foreign occupation during WW II as an interruption of democracy; sources: PT and BMVW |

EDUGER: |

Total enrollment in primary and secondary education as a percentage of the relevant age group in the country’s population, based on values for 1998 and 1999; sources: PT and BMVW |

FEDERAL: |

Dummy variable equal to 1 if a country has a federal political structure, 0 otherwise; sources: PT and BMVW |

FRENCHLO: |

Dummy for French law legal origin, coded 1 if legal origin is French law, 0 if legal origin is any other |

GASTIL: |

Average of indexes for civil liberties and political rights, each index is measured on a 1–7 scale with 1 representing the lowest degree of freedom. Countries whose averages are between 1 and 2.5 are deemed “not free,” those between 3 and 5.5 “partially free,” and those between 5.5 and 7 as “free”; sources: PT and BMVW |

GERMANLO: |

Dummy for German law legal origin, coded 1 if legal origin is German law, 0 if legal origin is any other |

GOVEF: |

Government effectiveness according to the Governance Indicators of the World Bank. Combines perceptions of the quality of public service provision, the quality of the bureaucracy, the competence of civil servants, the independence of the civil service from political pressures, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to policies into a single indicator. Values between 0 and 10, where higher values signal higher effectiveness; average values for 1996, 1998, 2000, 2002, and 2004; sources: PT and BMVW |

GRAFT: |

Graft according to the Governance Indicators of the World Bank focusing on perceptions of corruption. Values between 0 and 10, where lower values signal higher effectiveness; average values for 1996, 1998, and 2000; source: Kaufmann, D., Worldbank (2005): Governance Indicators: 1996–2004 |

IDEOLOGICAL PREFERENCES 1: |

Summed percentage of respondents who answered “1”, “2”, “3” or “4” on a scale from 1 to 10 where 1 = left to the question “In political matters, people talk of “the left” and “the right”. How would you place your views on this scale, generally speaking?”; source: V114 (World Values Survey 2005/6) |

IDEOLOGICAL PREFERENCES 2: |

Political party affiliations of both the executive and the legislature coded –1 if both executive and legislature are right-leaning, 1 if both are left-leaning, and 0 otherwise; source: Whytock (2007) |

INIT_DEBT: |

Initial indebtedness of a country as a share of its GDP in the first year for which data were available (INIT_DEBT = (Domestic Debt + Foreign Debt)/GDP); source: International Monetary Fund (2006); International Financial Statistics Online Service |

LAAM: |

Regional dummy variable, equal to 1 if a country is in Latin America, Central America, or the Caribbean, 0 otherwise; source: PT |

LAT01: |

Rescaled variable for latitude, defined as the absolute value of LATITUDE divided by 90 and taking on values between 0 and 1; sources: PT and BMVW |

LPOP: |

Natural logarithm of total population (in millions); sources: PT and BMVW |

LYP: |

Natural logarithm of real GDP per capita in constant dollars (chain index) expressed in international prices, base year 1985; average for the years 1990–1999; sources: PT and BMVW |

MAGN: |

Inverse of district magnitude, defined as DISTRICTS/SEATS. MAGN is a measure for the degree of political competition and can take on values between 0 and 1. Small values of MAGN indicate a high degree of political competition; sources: PT and BMVW |

MAJ: |

Dummy variable for electoral systems, equal to 1 if all the lower house in a country is elected under plurality rule, 0 otherwise. Only legislative elections (lower house) are considered; sources: PT and BMVW |

OECD: |

Dummy variable, equal to 1 for all countries that were members of the OECD; source: PT and BMVW |

POLITICAL COHESION: |

The variable can take on values between 0 and 1. It is coded such that 0 indicates the absence of any political competition whatsoever.; source: Beck et al. (2000) |

POLITICAL CONFLICT INDEX: |

The Political Conflict Index is composed of eight single variables, namely, number of assassinations, number of general strikes, occurrence of guerilla warfare, occurrence of government crises, purges, riots, revolutions, and anti-government demonstrations; source: Banks (2004) |

POPDENSITY: |

Number of inhabitants per hectare; source: Banks (2004) |

PRES: |

Dummy variable for government forms, equal to 1 in presidential regimes, 0 otherwise. Only regimes in which the confidence of the assembly is not necessary for the executive to stay in power (even if an elected president is not chief executive, or if there is no elected president) are included among presidential regimes Most semi-presidential and premier-presidential systems are classified as parliamentary; sources: constitutions and electoral laws, PT and BMVW |

PRESS-FREEDOM: |

Takes on values between 0 and 100; in countries coded between 0 and 30, the press is called “free”, 31–60 as “partially free” and 61–100 “not free; source: Freedom house at: http://www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=274 |

PROP1564: |

Percentage of a country’s population between 15 and 64 years old among entire population; sources: PT and BMVW |

PROP65: |

Percentage of a country’s population over the age of 65 in the total population; sources: PT and BMVW |

PROT80: |

Percentage of the population in a country professing the Protestant religion in 1980 (younger states are counted based on their average from 1990 to 1995); sources: PT and BMVW |

RULE_OF_LAW: |

Indicator for the rule of law which can take on values between 1 (best protection) and 5 (worst protection); source: Heritage/Wall Street Journal Index of Economic Freedom |

SCANLO: |

Dummy for Scandinavian law legal origin, coded 1 if legal origin is Scandinavian law, 0 if legal origin is any other |

SOCLO: |

Dummy for socialist law legal origin, coded 1 if legal origin is socialist law, 0 if legal origin is any other |

SPL: |

Central government budget surplus (if positive) or deficit (if negative) as a percentage of GDP, based on “DEFICIT (\(-\)) OR SURPLUS” as share of GDP average for 1990–1999; sources: PT and BMVW |

SSW: |

Central government expenditures consolidated on social services and welfare as a percentage of GDP; sources: PT and BMVW |

TOTEXP: |

Total government expenditure as share of GDP; source: BMVW |

TRADE: |

Sum of exports plus imports of goods and services measured as a share of GDP; sources: PT and BMVW |

Appendix 2

See Table 12.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blume, L., Voigt, S. Institutional details matter—more economic effects of direct democracy. Econ Gov 13, 287–310 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-012-0115-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-012-0115-9