Abstract

Introduction

Evaluation of apathy in non-clinical populations is relevant to identify individuals at risk for developing cognitive decline in later stages of life, and it should be performed with questionnaires specifically designed for healthy individuals, such as the Apathy-Motivation Index (AMI); therefore, the aim of the present study was to validate the AMI in a healthy Italian population, and to provide normative data of the scale.

Materials and methods

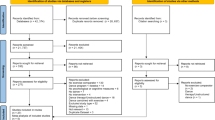

Data collection was performed using a survey completed by 500 healthy participants; DAS, MMQ-A, BIS-15, PHQ-9, and GAD-7 were used to investigate convergent and divergent validity. Internal consistency and factorial structure were also evaluated. A regression-based procedure and receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analyses were used to evaluate the influence of socio-demographic variables on AMI scores and to provide adjusting factors and three cut-offs for the detection of mild, moderate, and severe apathy.

Results

The Italian version of the AMI included 17 items (one item was removed because it was not internally consistent) and demonstrated good psychometric properties. The three-factor structure of AMI was confirmed. Multiple regression analysis revealed no effect of sociodemographic variables on the total AMI score. ROC analyses revealed three cut-offs of 1.5, 1.66, and 2.06 through the Youden’s J statistic to detect mild, moderate, and severe apathy, respectively.

Conclusion

The Italian version of the AMI reported similar psychometric properties, factorial structure, and cut-offs to the original scale. This may help researchers and clinicians to identify people at risk and address them in specific interventions to lower their apathy levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Apathy is defined as a reduction in motivation and frequency of goal-directed cognitive, emotional, and/or social activities with respect to a previous level of functioning [1]. As a neuropsychiatric syndrome, apathy occurs in several neurological diseases; positive associations between levels of apathy and cognitive dysfunctions have been observed in mild cognitive impairment [2, 3], dementia [4], Parkinson’s disease [5,6,7], multiple sclerosis [8, 9], amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [10], Huntington’s disease [11], and stroke [12]. Moreover, apathy has been found to be a risk factor for cognitive decline over time and conversion to frank dementia [13,14,15,16,17], and higher levels of apathy seem to be associated with lower levels of cognitive reserve [18] — the ability of the brain to cope with physiological or pathological brain damage and to protect against dementia in older age [19]. Taking into account these assumptions, it seems relevant to evaluate apathy in non-clinical populations to identify early apathetic individuals at high risk of developing cognitive decline.

Apathetic behavior has been evaluated using different tools such as the Apathy Evaluation Scale [20], Starkstein Apathy Scale [21], Apathy Inventory [22], Lille Apathy Rating Scale [23, 24], and Dimensional Apathy Scale [25]. Most of these questionnaires were adapted and validated for the Italian population [26,27,28,29] with mixed levels of study quality [30]. These tools were originally conceived for use in clinical populations, especially in patients with neurological conditions. The few questionnaires developed for the general population do not specifically assess apathetic behaviors, but they focus only on levels and types of motivation; moreover, cut-off values for lack of motivation are not provided [31].

Recently, a novel self-report questionnaire, the Apathy-Motivation Index (AMI) [32], was developed to fill this gap in the literature and to be employed in healthy people. AMI was created by a team of clinical neurologists and researchers with expertise in apathy, taking into account the multidimensional approach provided by a structured interview for neurological patients, the Lille Apathy Rating Scale [23, 24], and creating a set of items reflecting three dimensions of apathy/lack of motivation: behavioral activation, social motivation, and emotional sensitivity. The exploratory factor analysis identified a clear three-factor structure, starting from a preliminary 51-item scale. The authors retained the six highest loading items for each factor, providing a final version of 18 items. The construct validity and internal reliability of AMI were adequate and acceptable; moreover, cut-off values were provided to identify people with moderate and severe apathy.

Considering that the presence of higher levels of apathy in otherwise healthy people may interfere not only with their quality of life and educational and job opportunities but also directly or indirectly increase the risk of dementia in later stages of life [18, 33, 34], a timely identification of people at risk may help to address these people to non-pharmacological programs designed to increase levels of motivation and counteract the effect of mild, moderate, or severe apathy, as detected by AMI scores. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to provide psychometric and diagnostic properties, as well as normative data, of the first Italian version of the AMI in an Italian non-clinical population.

Materials and methods

Participants

Participants were recruited through an online survey created on Google Forms. Data were acquired from April 20 to June 24, 2021. The survey was disseminated using a snowball sampling strategy to university students and psychologist trainees, who were asked to distribute the online survey to their families, friends, and acquaintances throughout the Italian territory. The link was also shared on social media platforms (i.e., Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp). Participants who reported being affected by neurological and/or psychiatric diseases or if they used psychotropic drugs at the time of the survey were excluded from the analyses. The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee and was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Structure of AMI

The original version of the AMI includes 18 items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (completely true) to 4 (completely untrue). Every item is negatively scored; thus, higher scores are indicative of more apathetic behavior. The scale includes three domains of apathy-motivation: behavioral activation (items 5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 15), social motivation (items 2, 3, 4, 8, 14, 17), and emotional sensitivity (items 1, 6, 7, 13, 16, 18). The score for each domain was obtained using the following formula: \(\frac{\mathrm{sum}\;\mathrm{of}\;\mathrm{items}\;\mathrm{of}\;\mathrm{the}\;\mathrm{specific}\;\mathrm{domain}}{\mathrm{number}\;\mathrm{of}\;\mathrm{items}\;\mathrm{in}\;\mathrm{the}\;\mathrm{specific}\;\mathrm{domain}}\). The total AMI score was computed by averaging the mean scores of the three domains.

Italian adaptation of AMI

The English version of AMI [32] was independently translated into Italian by two researchers. The two versions were merged into a draft, and possible discrepancies were discussed among the authors to reach an agreement. According to the guidelines of Beaton and colleagues [35], the Italian draft was back translated into English by a native English speaker with expertise in linguistics and psychology. The back-translated and original English versions of the AMI were compared to evaluate the linguistic and psychological equivalence of the two versions. The two versions were defined as being equivalent. Finally, the linguistic comprehensibility of each item of the Italian version of AMI was tested by administering the scale to a group of 25 participants (aged 18–65 years old); no item was judged incomprehensible by participants, and the translated version of AMI was considered final.

Structure of the survey and psychological-behavioral assessment

The online survey included:

-

1)

Informed consent form: before being able to complete the online survey, every participant needed to provide their consent to participate in the study;

-

2)

A sociodemographic questionnaire aimed at collecting data about sex, age, and years of education for each participant. The possible occurrence of current and/or past neurological and psychiatric diseases and the use of psychotropic drugs were also investigated;

-

3)

The Italian version of AMI;

-

4)

The Dimensional Apathy Scale (DAS) [29] to evaluate the levels of apathy and convergent validity;

-

5)

The ability subscale of the Multifactorial Memory Questionnaire (MMQ-A) [36] to evaluate subjective memory functioning, particularly the frequency of memory problems;

-

6)

The short version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-15) [37] to assess levels of impulsivity;

-

7)

The 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [38] to evaluate depressive symptomatology;

-

8)

The 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7) [39] to assess severity of anxiety.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26. Acceptability of the AMI was defined by low percentages of missing values and floor and ceiling effects, according to previous studies on the standardization of behavioral scales [37, 40].

We checked univariate normality through skewness and kurtosis values. Values not exceeding |2| typically indicate no significant distortions from the Gaussian distribution [41].

The internal consistency was tested by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. We obtained additional evidence on the reliability and scaling assumptions for each item by computing Pearson’s item-total correlations and corrected item-total correlations to adjust for inflation errors [32, 42]. We interpreted the effect size according to Cohen’s conventions (weak, r < 0.30; moderate, r = 0.30–0.50; strong, r > 0.50) [43].

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS. We assessed the model fit using root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR), and comparative fit index (CFI). We adopted a cut-off of 0.80 for CFI and of < 0.08 for RMSEA and SRMR in line with previous investigations [32].

Convergent validity was assessed by Pearson’s correlation between AMI and DAS total scores, while divergent validity was evaluated by the correlation between the AMI total score and the scores of the PHQ-9, GAD-7, BIS-15, and MMQ. We also evaluated the potential influence of demographic factors (i.e., age, educational level, and sex) on the total AMI score through a multiple linear regression analysis.

Diagnostic accuracy was evaluated via receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis. A score above the 95th percentile of the DAS total score was employed as the state variable. Intrinsic properties — sensitivity (Se) and specificity (Sp) — were determined, and the optimal cut-off was identified through the Youden’s J statistic. Two additional cut-offs were identified for moderate and severe apathy on the AMI to be respectively > 1 SD and > 2 SD above the mean following the original scale [32].

Results

The online questionnaire was completed by 648 participants. Nevertheless, 148 participants who reported the presence of neurological/psychiatric conditions, cognitive decline, or ongoing treatment with psychotropic drugs were excluded. Hence, the final sample consisted of 500 participants (146 men and 354 women; see also Tables 1 and 2) with a mean age of 37.22 (SD = 13.67) and an average educational level of 15.32 years (SD = 2.52).

No significant differences emerged between males and females on age (F(1, 498) = 2.981, p = 0.085) and educational level (F(1, 498) = 2.120, p = 0.146). Each variable under examination did not exceed the normality range |2| for skewness and kurtosis values. No missing data or floor or ceiling effects were detected.

Multiple regression analysis aimed at evaluating the possible effect of sociodemographic variables on AMI total score revealed that the effect of sex, age, and educational level on AMI total score was not significant.

Reliability

Most of the items of the AMI were moderately (items 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17; r range = 0.393–0.496, ps < 0.001) correlated with the total score (see Table 3). Except for item 8, these items showed an acceptable level of discrimination (corrected item-total correlations, range = 0.287–0.377). Some items (items 1, 5, 7, 18) showed weak-to-moderate correlations (r range = 0.232–0.375) with the total score and a low level of discrimination (corrected item-total correlations, range = 0.118–0.261). Otherwise, item 6 was weakly correlated with the total score (r = 0.089, p = 0.047) and demonstrated a very poor level of discrimination (corrected item-total correlation = − 0.070). Taken together, these results indicated that item 6 was not internally consistent and deserved to be excluded; thus, we will now refer to a 17-items AMI scale without considering item 6 (for the scale translated into the Italian language see Supplementary Material 1; for the scoring sheet see Supplementary Material 2).

However, the whole scale demonstrated fair internal consistency, as shown by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.658, which increased (0.686) with the exclusion of item 6.

Confirmatory factor analysis

We confirmed the three-factor structure of the AMI with model fit indices almost identical to the original scale (Ang et al., 2017) (RMSEA = 0.073 with 90% CI = 0.065–0.080; SRMR = 0.074; CFI = 0.819).

The first factor included items evaluating the capabilities to feel positive and negative affections such as “I feel sad or upset when I hear bad news” and “Based on the last two weeks, I would say I care deeply about how my loved ones think of me” and thus, loaded under the emotional sensitivity factor. The second factor consisted of items reflecting behavioral activation like “When I decide to do something, I am able to make an effort easily” and “I get things done when they need to be done, without requiring reminders from others.” The third factor was composed of items indicating the level of engagement in social interactions and loading on a social motivation dimension such as “I suggest activities for me and my friends to do” and “I start conversations without being prompted.”

Convergent and divergent validity

Convergent validity was demonstrated by a significant strong correlation between AMI and DAS total scores (r = 0.594, p < 0.001). Conversely, divergent validity was explored by correlating the AMI scores with the PHQ-9, GAD-7, and BIS-15. We found positive and significant correlations with PHQ-9 (r = 0.225, p < 0.001) and BIS-15 (r = 0.199, p < 0.001), and negative and significant association with the ability subscale of MMQ (r = − 0.184, p < 0.001); on the other hand, AMI was not associated with GAD-7 (r = 0.051, p = 0.258).

Diagnostic accuracy and normative data

We carried out ROC analysis using a score above the 95th percentile on the DAS as gold standard. According to this operationalization, 11 participants (2.2%) were classified as apathetic.

AMI demonstrated high accuracy in detecting apathetic and non-apathetic individuals (AUC = 0.907; SE = 0.026; CI 95% [0.855, 0.959]; Fig. 1) with good intrinsic properties (Se = 1.000; Sp = 0.744). The optimal cut-off score for mild apathy was 1.5 (J = 0.744). Based on the original study on AMI [32], we proposed two additional cut-offs to identify moderate (> 1 SD = 1.66) and severe (> 2 SD = 2.06) apathy.

Discussion

The present study aimed at providing an Italian version of the AMI, a novel self-administered instrument to assess levels of apathy in non-clinical individuals.

The Italian version of AMI may represent a suitable questionnaire to evaluate levels of apathy and motivation in healthy individuals for the following reasons: (a) unlike other scales of apathy, it was developed specifically for the general population, and it includes items designed to evaluate a range of activities targeted for healthy adults; (b) it provides cut-offs for detecting mild, moderate, and severe apathy (1.5, 1.66, and 2.06, respectively); and (c) it shows good psychometric properties.

Our findings confirmed fair internal consistency of the scale and an acceptable level of discrimination, similar to the original study [32]. In contrast to the original version, the Italian version of the AMI included 17 items, as one item (item 6 of the original scale) was excluded due to its weak correlation with the total score and its poor level of discrimination. Nonetheless, the Italian version of the AMI confirmed the structure of the original scale, revealing the presence of three factors: emotional sensitivity (the ability to feel positive and negative emotions), behavioral activation (engaging in goal-directed behavioral activity), and social motivation (being able to engage in social interactions) [32].

Moreover, divergent and convergent validity was demonstrated by our correlational results: the strongest association was found between AMI and DAS scores, as expected, whereas significant but weak associations were found between AMI and PHQ-9, BIS-15, and MMQ-A. In particular, our finding of a weak but significant association between apathetic and depressive symptoms may provide indirect evidence that these are two dissociated syndromes, although they share some overlapping manifestations [44, 45]. With regard to the negative association between AMI and MMQ-A scores, this finding suggests that higher levels of apathy may be linked to perceived memory dysfunctions not only in people with dementia [46] but also in people with preserved cognitive functioning. This issue should be explored in future studies by employing a comprehensive neuropsychological battery to assess other cognitive domains. Furthermore, the link between apathy and impulsiveness suggests the possible co-existence of these two syndromes affecting motivation, thereby rejecting their conceptualization as merely opposite ends of a single continuum [47], as already found in clinical populations (i.e., Parkinson’s disease or progressive supranuclear palsy) [48,49,50].

Our results also showed that AMI scores were not predicted by age, education, or sex of participants, in line with a previous investigation in healthy participants [51]. Moreover, the non-significant effect of formal education, the most common proxy of cognitive reserve, may suggest that not every proxy of cognitive reserve is equally associated with lower levels of apathy in healthy people, but this correlation may be found only for specific cognitive stimulating activities related to cognitive reserve, such as social and leisure activities [18]. Future studies could further explore the role of other sociodemographic and/or psychological variables (i.e., personality characteristics and/or several proxies of cognitive reserve) in apathetic behaviors. Finally, our cut-offs for detecting mild, moderate, and severe apathy in our Italian sample do not seem to differ significantly from the original English scale; this may be due to the relatively low cultural proximity between Italy and the UK. Future studies should focus on the possible differences in emotional sensitivity, behavioral activation, and social motivation in healthy adults living in countries with various degrees of cultural proximity.

One limitation of the present study is related to the sampling strategy, and a sampling bias could not be excluded; even if participants were from northern, central, and southern regions of Italy, most of the sample was from Southern Italy, and since the survey was disseminated via an online link, people with internet access problems may have been underrepresented. Finally, it should be noted that the validation of the present scale was not performed in a clinical setting, but the participants were asked to complete the behavioral scales by themselves at home. Therefore, future studies should evaluate possible differences in AMI scores across different settings (clinical vs. non-clinical settings).

In conclusion, the proposed cut-offs of AMI for mild, moderate, and severe apathy may help researchers and clinicians to identify people with lower levels of motivation and higher levels of apathy in the general population, which should be addressed by specific and tailored psychosocial and/or psychotherapy interventions to increase their emotional sensitivity, behavioral activation, and social motivation, and to reduce the risk of cognitive decline in later stages of life.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Robert P, Lanctôt KL, Agüera-Ortiz L et al (2018) Is it time to revise the diagnostic criteria for apathy in brain disorders? The 2018 international consensus group. Eur Psychiatry 54:71–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.07.008

Bayard S, Jacus J-P, Raffard S, Gely-Nargeot M-C (2014) Apathy and emotion-based decision-making in amnesic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Behav Neurol 2014:231469. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/231469

Martin E, Velayudhan L (2020) Neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment: a literature review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 49:146–155. https://doi.org/10.1159/000507078

Eggins P, Wong S, Wei G et al (2022) A shared cognitive and neural basis underpinning cognitive apathy and planning in behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex 154:241–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2022.05.012

Santangelo G, Trojano L, Barone P et al (2013) Apathy in Parkinson’s disease: diagnosis, neuropsychological correlates, pathophysiology and treatment. Behav Neurol 27:501–513. https://doi.org/10.3233/BEN-129025

Santangelo G, D’Iorio A, Maggi G et al (2018) Cognitive correlates of “pure apathy” in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 53:101–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.04.023

D’Iorio A, Maggi G, Vitale C et al (2018) “Pure apathy” and cognitive dysfunctions in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analytic study. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 94:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.08.004

Novo AM, Batista S, Tenente J et al (2016) Apathy in multiple sclerosis: gender matters. J Clin Neurosci 33:100–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2016.02.038

Raimo S, Trojano L, Spitaleri D et al (2016) The relationships between apathy and executive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Neuropsychology 30:767–774. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000279

Kutlubaev MA, Caga J, Xu Y et al (2022) Apathy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis of frequency, correlates, and outcomes. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/21678421.2022.2053721

Hendel RK, Hellem MNN, Hjermind LE et al (2022) On the association between apathy and deficits of social cognition and executive functions in Huntington’s disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617722000364

Tay J, Morris RG, Markus HS (2021) Apathy after stroke: diagnosis, mechanisms, consequences, and treatment. Int J Stroke 16:510–518. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493021990906

Zhao J, Jin X, Chen B et al (2021) Apathy symptoms increase the risk of dementia conversion: a case-matching cohort study on patients with post-stroke mild cognitive impairment in China. Psychogeriatrics 21:149–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12634

Fan Z, Wang L, Zhang H et al (2021) Apathy as a risky neuropsychiatric syndrome of progression from normal aging to mild cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry 12:792168. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.792168

Tay J, Morris RG, Tuladhar AM et al (2020) Apathy, but not depression, predicts all-cause dementia in cerebral small vessel disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 91:953–959. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2020-323092

Raimo S, Spitaleri D, Trojano L, Santangelo G (2020) Apathy as a herald of cognitive changes in multiple sclerosis: a 2-year follow-up study. Mult Scler 26:363–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458519828296

Dujardin K, Sockeel P, Delliaux M et al (2009) Apathy may herald cognitive decline and dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 24:2391–2397. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.22843

Altieri M, Trojano L, Gallo A, Santangelo G (2020) The relationships between cognitive reserve and psychological symptoms: a cross-sectional study in healthy individuals. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 28:404–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2019.07.017

Stern Y (2009) Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia 47:2015–2028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.03.004

Marin RS (1991) Apathy: a neuropsychiatric syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 3:243–254. https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.3.3.243

Starkstein SE, Mayberg HS, Preziosi TJ et al (1992) Reliability, validity, and clinical correlates of apathy in Parkinson’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 4:134–139. https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.4.2.134

Robert PH, Clairet S, Benoit M et al (2002) The apathy inventory: assessment of apathy and awareness in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 17:1099–1105. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.755

Sockeel P, Dujardin K, Devos D et al (2006) The Lille apathy rating scale (LARS), a new instrument for detecting and quantifying apathy: validation in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 77:579–584. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2005.075929

Dujardin K, Sockeel P, Delliaux M et al (2008) The Lille Apathy Rating Scale: validation of a caregiver-based version. Mov Disord 23:845–849. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.21968

Radakovic R, Abrahams S (2014) Developing a new apathy measurement scale: Dimensional Apathy Scale. Psychiatry Res 219:658–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.06.010

Borgi M, Caccamo F, Giuliani A et al (2016) Validation of the Italian version of the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES-I) in institutionalized geriatric patients. Ann Ist Super Sanita 52:249–255. https://doi.org/10.4415/ANN_16_02_17

Garofalo E, Iavarone A, Chieffi S et al (2021) Italian version of the Starkstein Apathy Scale (SAS-I) and a shortened version (SAS-6) to assess “pure apathy” symptoms: normative study on 392 individuals. Neurol Sci 42:1065–1072. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04631-y

Furneri G, Platania S, Privitera A et al (2021) The Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES-C): psychometric properties and invariance of Italian version in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:9597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189597

Santangelo G, Raimo S, Siciliano M et al (2017) Assessment of apathy independent of physical disability: validation of the Dimensional Apathy Scale in Italian healthy sample. Neurol Sci 38:303–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-016-2766-8

Aiello EN, D’Iorio A, Montemurro S et al (2022) Psychometrics, diagnostics and usability of Italian tools assessing behavioural and functional outcomes in neurological, geriatric and psychiatric disorders: a systematic review. Neurol Sci 43:6189–6214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06300-8

Weiser M, Garibaldi G (2015) Quantifying motivational deficits and apathy: a review of the literature. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 25:1060–1081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.08.018

Ang Y-S, Lockwood P, Apps MAJ et al (2017) Distinct Subtypes of Apathy Revealed by the Apathy Motivation Index. PLoS One 12:e0169938. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169938

Vansteenkiste M, Lens W, De Witte S et al (2004) The ‘why’ and ‘why not’ of job search behaviour: their relation to searching, unemployment experience, and well-being. Eur J Soc Psychol 34:345–363. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.202

Vansteenkiste M, Lens W, De Witte H, Feather NT (2005) Understanding unemployed people’s job search behaviour, unemployment experience and well-being: a comparison of expectancy-value theory and self-determination theory. Br J Soc Psychol 44:268–287. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466604X17641

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB (2000) Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 25:3186–3191. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014

Raimo S, Trojano L, Siciliano M et al (2016) Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the multifactorial memory questionnaire for adults and the elderly. Neurol Sci 37:681–691. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-016-2562-5

Maggi G, Altieri M, Ilardi CR, Santangelo G (2022) Validation of a short Italian version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-15) in non-clinical subjects: psychometric properties and normative data. Neurol Sci 43:4719–4727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06047-2

Mazzotti E, Fassone G, Picardi A et al (2003) II Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) per lo screening dei disturbi psichiatrici: Uno studio di validazione nei confronti della Intervista Clinica Strutturata per il DSM-IV asse I (SCID-I). Ital J Psychopathol 9:235–242

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166:1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Maggi G, D’Iorio A, Aiello EN et al (2023) Psychometrics and diagnostics of the Italian version of the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) in Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-06619-w

Llevot A, Astruc D (2012) Applications of vectorized gold nanoparticles to the diagnosis and therapy of cancer. Chem Soc Rev 41:242–257. https://doi.org/10.1039/c1cs15080d

Ilardi CR, Gamboz N, Iavarone A et al (2021) Psychometric properties of the STAI-Y scales and normative data in an Italian elderly population. Aging Clin Exp Res 33:2759–2766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-021-01815-0

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Routledge, New York

Levy ML, Cummings JL, Fairbanks LA et al (1998) Apathy is not depression. JNP 10:314–319. https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.10.3.314

Mortby ME, Maercker A, Forstmeier S (2012) Apathy: a separate syndrome from depression in dementia? A critical review. Aging Clin Exp Res 24:305–316. https://doi.org/10.3275/8105

Yu S-Y, Lian T-H, Guo P et al (2020) Correlations of apathy with clinical symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease and olfactory dysfunctions: a cross-sectional study. BMC Neurol 20:416. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-020-01978-9

Petitet P, Scholl J, Attaallah B et al (2021) The relationship between apathy and impulsivity in large population samples. Sci Rep 11:4830. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84364-w

Palmeri R, Corallo F, Bonanno L et al (2022) Apathy and impulsiveness in Parkinson disease: Two faces of the same coin? Medicine 101:e29766. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000029766

Kok ZQ, Murley AG, Rittman T et al (2021) Co-occurrence of apathy and impulsivity in progressive supranuclear palsy. Mov Disord Clin Pract 8:1225–1233. https://doi.org/10.1002/mdc3.13339

Santangelo G, Raimo S, Barone P (2017) The relationship between impulse control disorders and cognitive dysfunctions in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 77:129–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.02.018

Pardini M, Cordano C, Guida S et al (2016) Prevalence and cognitive underpinnings of isolated apathy in young healthy subjects. J Affect Disord 189:272–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.062

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli,” and it was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed consent

Each participant provided a written informed consent to the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Altieri, M., Maggi, G., Rippa, V. et al. Evaluation of apathy in non-clinical populations: validation, psychometric properties, and normative data of the Italian version of Apathy-Motivation Index (AMI). Neurol Sci 44, 3099–3106 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-06774-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-06774-0