Abstract

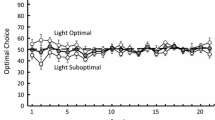

The ability to control impulsive behaviour has been studied in animals with a standard test in which subjects need to choose the smaller of two food items in order to receive the larger one (reverse reward contingency). As a variety of mammals that have been tested so far (mostly primates) have great difficulties to solve the task, it has been proposed that it is generally cognitively demanding. However, according to an ecological approach to cognition, a species’ ability to solve the task should not depend on its general cognitive abilities but on whether its ecology causes selective pressure on the ability to restrain foraging behaviour. We tested this hypothesis using the cleaner wrasse (Labroides dimidiatus), a fish species that feeds against its preference in nature when engaging in cleaning interactions with so called ‘client fish’. None of the eight tested individuals learned to choose a non-preferred item after 200 trials. In a subsequent test, one subject learned to respond correctly in a large or none contingency task (only the choice of the small food was rewarded). After a short re-experience treatment, this individual learned to solve the reverse reward task after 30 trials. In conclusion, we did not find support for the general idea that interactions with clients prepared cleaners to quickly solve a reverse reward test. However, the results suggest that the potential to solve a reverse reward contingency may not be restricted to mammals but could be present also in a fish species in which the problem of choosing a non-preferred food over a preferred one is an ever present challenge in nature.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abeyesinghe SM, Nicol CJ, Hartnell SJ, Wathes CM (2005) Can domestic fowl, Gallus gallus domesticus, show self-control? Anim Behav 70:1–11

Albiach-Serrano A, Guillen-Salazar F, Call J (2007) Mangabeys (Cercocebus torquatus lunulatus) solve the reverse contingency task without a modified procedure. Anim Cogn 10:387–396

Anderson JR, Awazu S, Fujita K (2000) Can squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) learn self-control? A study using food array selection tests and reverse-reward contingency. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process 26:87–97

Bergmüller R, Johnstone RA, Russell AF, Bshary R (2007a) Integrating cooperative breeding into theoretical concepts of cooperation. Behav Process 76:61–72

Bergmüller R, Russell AF, Johnstone RA, Bshary R (2007b) On the further integration of cooperative breeding and cooperation theory. Behav Process 76:170–181

Boysen ST, Berntson GG (1995) Responses to quantity: perceptual versus cognitive mechanisms in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process 21:82–86

Boysen ST, Berntson GG, Hannan MB, Cacioppo JT (1996) Quantity-based interference and symbolic representations in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process 22:76–86

Boysen ST, Mukobi KL, Berntson GG (1999) Overcoming response bias using symbolic representations of number by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Anim Learn Behav 27:229–235

Bshary R (2001) The cleaner fish market. In: Noë R, van Hooff JARAM, Hammerstein P (eds) Economics in nature. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge pp 146–172

Bshary R, Bergmüller R (2008) Distinguishing four fundamental approaches to the evolution of helping. J Evol Biol 21:405–420

Bshary R, Grutter AS (2002a) Experimental evidence that partner choice is a driving force in the payoff distribution among cooperators or mutualists: the cleaner fish case. Ecol Lett 5:130–136

Bshary R, Grutter AS (2002b) Parasite distribution on client reef fish determines cleaner fish foraging patterns. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 235:217–222

Bshary R, Grutter AS (2005) Punishment and partner switching cause cooperative behaviour in a cleaning mutualism. Biol Lett 1:396–399

Bshary R, Grutter AS (2006) Image scoring and cooperation in a cleaner fish mutualism. Nature 441:975–978

Bshary R, Schäffer D (2002) Choosy reef fish select cleaner fish that provide high-quality service. Anim Behav 63:557–564

Bshary R, Wickler W, Fricke H (2002) Fish cognition: a primate’s eye view. Anim Cogn 5:1–13

Bshary R, Salwiczek L, Wickler W (2007) Social cognition in non primates. In: Dunbar R, Barrett L (eds) The Oxford handbook of evolutionary psychology. Oxford Handbooks in Psychology, Oxford

Bshary R, Grutter AS, Willener AST, Leimar O (2008) Pairs of cooperating cleaner fish provide better service quality than singletons. Nature 455:964–966

Genty E, Roeder JJ (2006) Self-control: why should sea lions, Zalophus californianus, perform better than primates? Anim Behav 72:1241–1247

Genty E, Palmier C, Roeder JJ (2004) Learning to suppress responses to the larger of two rewards in two species of lemurs, Eulemur fulvus and E. macaco. Anim Behav 67:925–932

Grutter A (1996) Parasite removal rates by the cleaner wrasse Labroides dimidiatus. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 130:61–70

Grutter AS, Bshary R (2003) Cleaner wrasse prefer client mucus: support for partner control mechanisms in cleaning interactions. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 270:S242–S244

Kamil AC (1998) On the proper definition of cognitive ethology. In: Balda RP, Pepperberg IM, Kamil AC (eds) Animal cognition in nature. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 1–28

Kralik JD, Hauser MD, Zimlicki R (2002) The relationship between problem solving and inhibitory control: cotton-top tamarin (Saguinus oedipus) performance on a reversed contingency task. J Comp Psychol 116:39–50

Landeau L, Terborgh J (1986) Oddity and the confusion effect in predation. Anim Behav 34:1372–1380

Mischel W, Shoda Y, Rodriguez ML (1989) Delay of gratification in children. Science 244:933–938

Murray EA, Kralik JD, Wise SP (2005) Learning to inhibit prepotent responses: successful performance by rhesus macaques, Macaca mulatta, on the reversed-contingency task. Anim Behav 69:991–998

Russell J, Mauthner N, Sharpe S, Tidswell T (1991) The “windows task” as a measure of strategic deception in preschoolers and autistic subjects. Br J Dev Psychol 9:331–349

Ruxton GD, Jackson AL, Tosh CR (2008) Confusion of predators does not rely on specialist coordinated behavior. Behav Ecol 18:590–596

Shettleworth SJ (1994) Biological approaches to the study of learning. In: Mackintosh NJ (ed) Animal learning an cognition. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 185–219

Shumaker RW, Palkovich AM, Beck BB, Guagnano GA, Morowitz H (2001) Spontaneous use of magnitude discrimination and ordination by the orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus). J Comp Psychol 115:385–391

Silberberg A, Fujita K (1996) Pointing at smaller food amounts in an analogue of Boysen and Berntson’s (1995) procedure. J Exp Anal Behav 66:143–147

Stevens JR, Hauser MD (2004) Why be nice? Psychological constraints on the evolution of cooperation. Trends Cogn Sci 8:60–65

Stevens JR, Cushman FA, Hauser MD (2005) Evolving the psychological mechanisms for cooperation. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 36:499–518

Uller C, Jaeger R, Guidry G, Martin C (2003) Salamanders (Plethodon cinereus) go for more: rudiments of number in an amphibian. Anim Cogn 6:105–112

West SA, Griffin AS, Gardner A (2007) Social semantics: altruism, cooperation, mutualism, strong reciprocity and group selection. J Evol Biol 20:415–432

Wittmann M, Paulus MP (2008) Decision making, impulsivity and time perception. Trends Cogn Sci 12:7–12

Acknowledgments

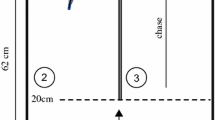

We are grateful to Sylvain Bruschweiler for help with producing Fig. 1 and Matthias Erb, Russell Naisbit, and four anonymous referees for helpful comments on the manuscript. We thank Anna Albiach Serrano and the Eco-Ethology group at the University of Neuchâtel for discussion, Jean-Pierre Duvoisin for technical assistance and Ana Pinto for her help with the fish. This study was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (to R. Bshary). The experiment was licensed by the Veterinary Commission of the Canton de Neuchâtel.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Danisman, E., Bshary, R. & Bergmüller, R. Do cleaner fish learn to feed against their preference in a reverse reward contingency task?. Anim Cogn 13, 41–49 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-009-0243-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-009-0243-y