Abstract

Objectives

Some patients with rheumatoid arthritis develop interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) that develops into progressive pulmonary fibrosis. We assessed the efficacy and safety of nintedanib versus placebo in patients with progressive RA-ILD in the INBUILD trial.

Methods

The INBUILD trial enrolled patients with fibrosing ILD (reticular abnormality with traction bronchiectasis, with or without honeycombing) on high-resolution computed tomography of >10% extent. Patients had shown progression of pulmonary fibrosis within the prior 24 months, despite management in clinical practice. Subjects were randomised to receive nintedanib or placebo.

Results

In the subgroup of 89 patients with RA-ILD, the rate of decline in FVC over 52 weeks was −82.6 mL/year in the nintedanib group versus −199.3 mL/year in the placebo group (difference 116.7 mL/year [95% CI 7.4, 226.1]; nominal p = 0.037). The most frequent adverse event was diarrhoea, which was reported in 61.9% and 27.7% of patients in the nintedanib and placebo groups, respectively, over the whole trial (median exposure: 17.4 months). Adverse events led to permanent discontinuation of trial drug in 23.8% and 17.0% of subjects in the nintedanib and placebo groups, respectively.

Conclusions

In the INBUILD trial, nintedanib slowed the decline in FVC in patients with progressive fibrosing RA-ILD, with adverse events that were largely manageable. The efficacy and safety of nintedanib in these patients were consistent with the overall trial population. A graphical abstract is available at: https://www.globalmedcomms.com/respiratory/INBUILD_RA-ILD.

Key Points • In patients with rheumatoid arthritis and progressive pulmonary fibrosis, nintedanib reduced the rate of decline in forced vital capacity (mL/year) over 52 weeks by 59% compared with placebo. • The adverse event profile of nintedanib was consistent with that previously observed in patients with pulmonary fibrosis, characterised mainly by diarrhoea. • The effect of nintedanib on slowing decline in forced vital capacity, and its safety profile, appeared to be consistent between patients who were taking DMARDs and/or glucocorticoids at baseline and the overall population of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and progressive pulmonary fibrosis. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) may occur as a manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [1, 2]. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans from patients with RA-ILD commonly show fibrotic as well as inflammatory features [3]. The clinical course of RA-ILD is variable and difficult to predict [4, 5]. Some patients with RA-ILD develop progressive pulmonary fibrosis characterised by increasing radiological fibrosis, decline in lung function, worsening symptoms, and early mortality [4,5,6,7,8]. It has been estimated that ILD is a contributor to mortality in up to 6.8% of women and 9.8% of men with RA [2]. As in patients with other ILDs, loss of forced vital capacity (FVC) is a predictor of mortality in patients with RA-ILD [9,10,11].

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and glucocorticoids are the standard of care for RA [12], but there is no evidence from randomised controlled trials that they slow the progression of pulmonary fibrosis. Nintedanib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor licensed for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), fibrosing ILD associated with systemic sclerosis (SSc), and progressive fibrosing ILDs of any aetiology. Pre-clinical studies have shown that nintedanib has anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects that slow the progression of pulmonary fibrosis, including inhibiting the release of pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory mediators, the migration and differentiation of fibroblasts, and the accumulation of extracellular matrix [13]. Nintedanib was given a conditional recommendation for use in patients with progressive pulmonary fibrosis who have failed “standard management” for ILD in international management guidelines [14]. In the randomised placebo-controlled INBUILD trial in patients with progressive fibrosing ILDs other than IPF, nintedanib slowed the progression of pulmonary fibrosis, with an adverse event profile characterised mainly by gastrointestinal events [15,16,17]. No heterogeneity was detected in the effect of nintedanib on reducing the rate of decline in FVC across diagnostic subgroups [15, 18, 19]. Here, we assessed the efficacy and safety of nintedanib in patients with progressive RA-ILD in the INBUILD trial.

Methods

Trial design

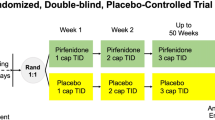

The INBUILD trial (NCT02999178) was a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted in 15 countries [15, 16]. The trial was conducted in accordance with the protocol, the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Harmonised Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice from the International Conference on Harmonisation and was approved by local authorities. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before study entry. The trial design has been described and the protocol is publicly available [15]. Briefly, patients had an ILD other than IPF with reticular abnormality with traction bronchiectasis (with or without honeycombing) of >10% extent on HRCT, FVC ≥45% predicted and diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLco) ≥30–<80% predicted. Patients met ≥1 of the following criteria for progression of pulmonary fibrosis within the prior 24 months, despite management deemed appropriate in clinical practice: relative decline in FVC ≥10% predicted; relative decline in FVC ≥5–<10% predicted and worsened respiratory symptoms; relative decline in FVC ≥5–<10% predicted and increased extent of fibrosis on HRCT; worsened respiratory symptoms and increased extent of fibrosis on HRCT. Azathioprine, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, oral glucocorticoids >20 mg/day, or the combination of oral glucocorticoids, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine was not permitted ≤4 weeks prior to randomisation; cyclophosphamide was not permitted ≤8 weeks prior to randomisation; rituximab was not permitted ≤6 months prior to randomisation; there was no limit on the use of stable doses of other biologic or non-biologic DMARDs. Use of glucocorticoids at a dose of ≤20 mg/day prednisone or equivalent was permitted. The immunomodulatory therapies that were not permitted at randomisation could be initiated after 6 months in patients with deterioration of ILD or connective tissue disease, but use of nintedanib (other than as trial drug) and pirfenidone was prohibited.

Patients were randomised to receive nintedanib 150 mg twice daily (bid) or placebo, stratified by fibrotic pattern on HRCT (usual interstitial pneumonia [UIP]-like fibrotic pattern or other fibrotic patterns [described in 15]). Treatment interruptions (for ≤4 weeks for adverse events considered related to trial medication or ≤8 weeks for other adverse events) and dose reductions to 100 mg bid were used to manage adverse events. After resolution of the adverse event, nintedanib could be reintroduced and/or the dose increased back to 150 mg bid. The trial consisted of two parts. Part A comprised 52 weeks of treatment. Part B was a variable period beyond week 52 during which patients continued to receive blinded treatment until all patients had completed the trial. Patients who discontinued treatment were asked to attend all visits as planned, including an end-of-treatment visit and a follow-up visit 4 weeks later. The final database lock took place after all patients had completed the follow-up visit or had entered the open-label extension study, INBUILD-ON (NCT03820726). The data available at final database lock comprised the data from the whole trial.

Outcomes

We assessed the rate of decline in FVC (mL/year) over 52 weeks in all patients with RA-ILD, in subgroups of patients with RA-ILD based on high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) at baseline (<1 vs ≥1 mg/L; <3 vs ≥3 mg/L) and in patients with RA-ILD taking DMARDs and/or glucocorticoids at baseline. DMARDs were identified based on the WHO Drug Dictionary (version 19.MAR) standardised drug grouping with the addition of baricitinib and the exclusion of denosumab. Glucocorticoids were identified based on the WHO Drug Dictionary standardised drug grouping.

We report the proportions of patients with RA-ILD with absolute and relative declines from baseline in FVC % predicted >10% at week 52. We also analysed the times to first acute exacerbation (defined in [15]) or death, first non-elective hospitalisation or death, first non-elective respiratory hospitalisation or death, progression of ILD (defined as an absolute decline from baseline in FVC % predicted ≥ 10%) or death, and death using data from the whole trial. Adverse events reported over the whole trial, irrespective of causality, were coded using preferred terms in the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 22.0 and are presented descriptively.

Analyses

Analyses were based on data from patients who received ≥1 dose of trial drug. The rate of decline in FVC (mL/year) over 52 weeks was analysed in patients with RA-ILD using a random coefficient regression model (with random slopes and intercepts) including baseline FVC (mL), HRCT pattern (UIP-like fibrotic pattern or other fibrotic patterns) and treatment, and treatment-by-time and baseline-by-time interactions. Subgroup analyses used the same model but with interaction terms for baseline-by-time, treatment-by-subgroup, and treatment-by-subgroup-by-time interaction. In subgroups by CRP at baseline, the interaction p-value (based on an F-test) was an indicator of potential heterogeneity of the effect of nintedanib versus placebo between the subgroups. The proportions of patients with absolute and relative declines in FVC >10% predicted at week 52 were analysed using logistic regression. Missing values at week 52 were imputed using multiple imputation. Cox proportional hazards models (stratified by HRCT pattern) with terms for treatment were used to derive hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). P-values were calculated based on a log-rank test stratified by HRCT pattern. Analyses were not adjusted for multiplicity.

Results

Patients

Of 663 patients in the INBUILD trial, 89 (13.4%) had RA-ILD. The RA diagnosis was confirmed by a rheumatologist in 83 of the 84 patients for whom these data were available. The baseline characteristics of the patients with RA-ILD have been described [19]. In summary, mean (SD) age was 66.9 (9.6) years, 60.7% were male, and 86.5% had a UIP-like fibrotic pattern on HRCT. Mean (SD) FVC was 71.5 (16.2) % predicted and mean (SD) DLco was 47.7 (15.6) % predicted. Mean (SD) times since diagnosis of RA and RA-ILD were 9.9 (9.4) years and 3.6 (3.2) years. Among patients with available CRP measurements, mean (SD) hs-CRP was 13.7 (22.5) mg/L; 64.7% of patients had hs-CRP ≥3.0 mg/L. A total of 21.3% were taking biologic DMARDs, 53.9% non-biologic DMARDs, and 73.0% glucocorticoids (Online Resource 1). The most common comorbidities were hypertension and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (Online Resource 2).

Exposure to medications

Median exposure to trial drug over the whole trial was 17.4 months in both groups. Based on medications taken at baseline, during treatment with trial drug, or following discontinuation of trial drug, the immunomodulatory therapies that were restricted at baseline were taken by higher proportions of patients in the placebo group than in the nintedanib group (Online Resource 3).

Decline in FVC

In this evaluation of patients with RA-ILD, the adjusted annual rate of decline in FVC over 52 weeks was −82.6 mL/year in the nintedanib group versus −199.3 mL/year in the placebo group (difference 116.7 mL/year [95% CI 7.4, 226.1]; nominal p = 0.037) (Table 1). Observed changes from baseline in FVC (mL) showed separation between treatment groups from week 24 (Fig. 1). Among these patients with RA-ILD, no heterogeneity was detected in the effect of nintedanib versus placebo on the rate of decline in FVC (mL/year) across subgroups by CRP at baseline (Fig. 2). Among patients with RA-ILD taking DMARDs and/or glucocorticoids at baseline, the adjusted annual rate of decline in FVC over 52 weeks was −90.4 mL/year in the nintedanib group (n = 39) versus −228.3 mL/year in the placebo group (n = 40) (difference 137.9 mL/year [95% CI 23.4, 252.5]). Smaller proportions of patients in the nintedanib group than in the placebo group had absolute and relative declines in FVC % predicted >10% at week 52 (Table 1).

Acute exacerbations, hospitalisations, progression of ILD, and death

Time to event endpoints over the whole trial are shown in Table 1 and Online Resource 4. Acute exacerbation of ILD or death occurred in 8 patients (19.0%) in the nintedanib group and 15 (31.9%) in the placebo group (HR 0.54 [95% CI 0.3, 1.28]; nominal p = 0.16). Hospitalisation or death occurred in 27 patients (64.3%) in the nintedanib group and 26 patients (55.3%) in the placebo group (HR 1.36 [95% CI 0.79, 2.34]; nominal p = 0.26), and respiratory hospitalisation or death in 18 patients (42.9%) in the nintedanib group and 22 patients (46.8%) in the placebo group (HR 0.87 [95% CI 0.46, 1.62]; nominal p = 0.65). Progression of ILD or death occurred in 19 patients (45.2%) in the nintedanib group and 29 patients (61.7%) in the placebo group (HR 0.63 [95% CI 0.35, 1.13]; nominal p = 0.12). Deaths occurred in 7 patients (16.7%) in the nintedanib group and 9 patients (19.2%) in the placebo group (HR 0.86 [95% CI 0.32, 2.31]; nominal p = 0.76).

Safety and tolerability

The most common adverse event reported in these patients with RA-ILD was diarrhoea, which was reported in 61.9% of patients in the nintedanib group and 27.7% of patients in the placebo group (Table 2). Diarrhoea occurred at a rate of 118 and 26 events per 100 patient-years in the nintedanib and placebo groups, respectively. Nausea was reported in 21.4% of patients in the nintedanib group and 12.8% of patients in the placebo group. Serious adverse events were reported in similar proportions of patients in the nintedanib and placebo groups (61.9% and 61.7%, respectively). Adverse events led to permanent dose reduction in 21.4% of patients in the nintedanib group and none in the placebo group. Adverse events led to treatment discontinuation in 23.8% of patients in the nintedanib group and 17.0% of patients in the placebo group. The most frequent adverse event leading to discontinuation of nintedanib was an increase in alanine aminotransferase, which led to discontinuation in 7.1% of patients. Gastrointestinal adverse events led to discontinuation of nintedanib in two (4.8%) patients.

Discussion

These data from the INBUILD trial show that nintedanib reduced the rate of decline in FVC over 52 weeks in patients with progressive fibrosing RA-ILD by 59% compared with placebo, similar to the relative treatment effect observed in the overall trial population [15], in patients with SSc-ILD [20] and in patients with IPF [21]. A recent meta-analysis of the effect of nintedanib on the rate of FVC decline across ILDs confirmed that there was no evidence of heterogeneity [22]. These findings provide further support for the hypothesis that the progressive pulmonary fibrosis that develops in a proportion of patients with various ILDs develops via common pathological pathways and that nintedanib inhibits pathways fundamental to the progression of pulmonary fibrosis [13, 23]. The later separation of the curves of change in FVC in the RA-ILD subgroup of the INBUILD trial than in the overall trial population may be a reflection of the relatively small size of this subgroup.

Decline in FVC in patients with ILDs is reflective of disease progression and is associated with mortality [9,10,11, 24, 25]. The patients with RA-ILD who participated in the INBUILD trial showed significant loss of lung function over 52 weeks, with a decline of over 200 mL of FVC observed in the placebo group. This highlights the importance of prompt identification and treatment of patients with RA who have progressive pulmonary fibrosis. Although some predictors of progressive RA-ILD have been identified [3, 6, 9, 10, 26, 27], the course of RA-ILD in an individual patient remains largely unpredictable, making regular monitoring of lung function an important part of the care of these patients. In clinical practice, progression of fibrosing ILD is usually assessed based on lung function tests performed every 3 to 6 months [28, 29].

CRP is a marker of inflammation [30]. In a prospective study of patients with SSc-ILD, elevated CRP was associated with greater decline in FVC and shorter survival [31], but it is unclear whether elevated CRP is associated with progression of RA-ILD. We found no heterogeneity in the effect of nintedanib between patients with differing CRP levels at baseline, consistent with findings in patients with SSc-ILD [32].

Acute exacerbations associated with high morbidity and mortality are a feature of the natural history of IPF [33] and have also been reported in patients with RA-ILD [8, 9, 34,35,36] and other autoimmune disease-related ILDs [37]. Over the whole INBUILD trial, 32% of the patients with progressive fibrosing RA-ILD who received placebo had an acute exacerbation of ILD or died. Treatment with nintedanib was associated with a numerically reduced risk of acute exacerbation of ILD or death (HR 0.54). This trend may be of clinical relevance given the lack of effective treatments for acute exacerbations of ILD.

The adverse event profile of nintedanib in patients with RA-ILD in the INBUILD trial was consistent with observations in the overall trial population [15,16,17] and in the subgroup of patients with autoimmune disease-related ILDs [19] as well as in patients with SSc-ILD [20, 38] and IPF [21, 39]. Diarrhoea was the most common adverse event, but fewer than 5% of the patients with RA-ILD discontinued nintedanib due to diarrhoea. In clinical practice, management of adverse events using symptomatic therapies and dose adjustment is important to minimise their impact and help patients remain on therapy.

DMARDs are an important part of the management of patients with RA, according to international management guidelines [12, 40] and most patients with RA are taking DMARDs and/or glucocorticoids [40]. There is little evidence to suggest that the use of DMARDs is associated with worsening of RA-ILD, although tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors may be associated with higher mortality than other DMARDs [41, 42]. Among patients with RA-ILD, the effect of nintedanib on reducing decline in FVC in patients who were taking DMARDs and/or glucocorticoids at baseline was similar to that observed in all patients with RA-ILD. Previous analyses of data from the overall INBUILD trial population supported this observation and suggested that the introduction of restricted immunomodulatory therapies during the trial had no impact on the effect of nintedanib [43]. However, it should be borne in mind that patients were not randomised by use of therapies other than nintedanib. Further research is needed into the effects of therapy with nintedanib and immunomodulators in patients with autoimmune disease-related ILDs.

Strengths of our analyses include the randomised placebo-controlled trial design, with standardised reporting of outcomes and adverse events. Limitations include that the INBUILD trial was not designed or powered to study individual ILDs and the number of patients with RA-ILD was small, limiting the potential for subgroup analyses including those based on concomitant medication use. There are no adequately validated patient-reported outcomes for assessing changes in symptoms or quality of life due to worsening of RA-ILD. Data on RA disease activity were not collected.

Conclusions

In the INBUILD trial, nintedanib slowed the rate of decline in FVC in patients with progressive fibrosing RA-ILD, with adverse events that were largely manageable. The efficacy and safety of nintedanib in these patients were consistent with the overall trial population.

Data availability

To ensure independent interpretation of clinical study results and enable authors to fulfill their role and obligations under the ICMJE criteria, Boehringer Ingelheim grants all external authors access to relevant clinical study data. In adherence with the Boehringer Ingelheim Policy on Transparency and Publication of Clinical Study Data, scientific and medical researchers can request access to clinical study data after publication of the primary manuscript in a peer-reviewed journal, regulatory activities are complete and other criteria are met. Researchers should use https://vivli.org/ to request access to study data and visit https://www.mystudywindow.com/msw/datasharing for further information.

References

Bongartz T, Nannini C, Medina-Velasquez YF, Achenbach SJ, Crowson CS, Ryu JH, Vassallo R, Gabriel SE, Matteson EL (2010) Incidence and mortality of interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum 62:1583–1591. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.27405

Olson AL, Swigris JJ, Sprunger DB, Fischer A, Fernandez-Perez ER, Solomon J, Murphy J, Cohen M, Raghu G, Brown KK (2011) Rheumatoid arthritis-interstitial lung disease-associated mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183:372–378. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201004-0622OC

Nurmi HM, Kettunen HP, Suoranta SK, Purokivi MK, Kärkkäinen MS, Selander TA, Kaarteenaho RL (2018) Several high-resolution computed tomography findings associate with survival and clinical features in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Respir Med 134:24–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2017.11.013

Hyldgaard C, Ellingsen T, Hilberg O, Bendstrup E (2019) Rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: clinical characteristics and predictors of mortality. Respiration 98:455–460. https://doi.org/10.1159/000502551

Mena-Vázquez N, Rojas-Gimenez M, Romero-Barco CM, Manrique-Arija S, Francisco E, Aguilar-Hurtado MC, Añón-Oñate I, Pérez-Albaladejo L, Ortega-Castro R, Godoy-Navarrete FJ, Ureña-Garnica I, Velloso-Feijoo ML, Redondo-Rodriguez R, Jimenez-Núñez FG, Panero Lamothe B, Padin-Martín MI, Fernández-Nebro A (2021) Predictors of progression and mortality in patients with prevalent rheumatoid arthritis and interstitial lung disease: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Med 10:874. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10040874

Zamora-Legoff JA, Krause ML, Crowson CS, Ryu JH, Matteson EL (2017) Progressive decline of lung function in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum 69:542–549. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.39971

Jacob J, Hirani N, van Moorsel CHM, Rajagopalan S, Murchison JT, van Es HW, Bartholmai BJ, van Beek FT, Struik MHL, Stewart GA, Kokosi M, Egashira R, Brun AL, Cross G, Barnett J, Devaraj A, Margaritopoulos G, Karwoski R, Renzoni E et al (2019) Predicting outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis related interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J 53:1800869. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00869-2018

Solomon JJ, Danoff SK, Woodhead FA, Hurwitz S, Maurer R, Glaspole I, Dellaripa PF, Gooptu B, Vassallo R, Cox PG, Flaherty KR, Adamali HI, Gibbons MA, Troy L, Forrest IA, Lasky JA, Spencer LG, Golden J, Scholand MB, Chaudhuri N, Perrella MA, Lynch DA, Chambers DC, Kolb M, Spino C, Raghu G, Goldberg HJ, Rosas IO; TRAIL1 network investigators (2022) Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of pirfenidone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Respir Med S2213-2600(22)00260. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00260-0.

Song JW, Lee HK, Lee CK, Chae EJ, Jang SJ, Colby TV, Kim DS (2013) Clinical course and outcome of rheumatoid arthritis-related usual interstitial pneumonia. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 30:103–112

Solomon JJ, Chung JH, Cosgrove GP, Demoruelle MK, Fernandez-Perez ER, Fischer A, Frankel SK, Hobbs SB, Huie TJ, Ketzer J, Mannina A, Olson AL, Russell G, Tsuchiya Y, Yunt ZX, Zelarney PT, Brown KK, Swigris JJ (2016) Predictors of mortality in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J 47:588–596. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00357-2015

Qiu M, Jiang J, Nian X, Wang Y, Yu P, Song J, Zou S (2021) Factors associated with mortality in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res 22:264. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-021-01856-z

Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, Burmester GR, Dougados M, Kerschbaumer A, McInnes IB, Sepriano A, van Vollenhoven RF, de Wit M, Aletaha D, Aringer M, Askling J, Balsa A, Boers M, den Broeder AA, Buch MH, Buttgereit F, Caporali R et al (2020) EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 79:685–699. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216655

Wollin L, Distler JHW, Redente EF, Riches DWH, Stowasser S, Schlenker-Herceg R, Maher TM, Kolb M (2019) Potential of nintedanib in treatment of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir J 54:1900161. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00161-2019

Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, Thomson CC, Inoue Y, Johkoh T, Kreuter M, Lynch DA, Maher TM, Martinez FJ, Molina-Molina M, Myers JL, Nicholson AG, Ryerson CJ, Strek ME, Troy LK, Wijsenbeek M, Mammen MJ, Hossain T et al (2022) Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 205:e18–e47. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

Flaherty KR, Wells AU, Cottin V, Devaraj A, Walsh SLF, Inoue Y, Richeldi L, Kolb M, Tetzlaff K, Stowasser S, Coeck C, Clerisme-Beaty E, Rosenstock B, Quaresma M, Haeufel T, Goeldner RG, Schlenker-Herceg R, Brown KK, INBUILD trial investigators (2019) Nintedanib in progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. N Engl J Med 381:1718–1727. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1908681

Flaherty KR, Wells AU, Cottin V, Devaraj A, Inoue Y, Richeldi L, Walsh SLF, Kolb M, Koschel D, Moua T, Stowasser S, Goeldner RG, Schlenker-Herceg R, Brown KK, INBUILD trial investigators (2022) Nintedanib in progressive interstitial lung diseases: data from the whole INBUILD trial. Eur Respir J 59:2004538. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.04538-2020

Cottin V, Martinez FJ, Jenkins RG, Belperio JA, Kitamura H, Molina-Molina M, Tschoepe I, Coeck C, Lievens D, Costabel U (2022) Safety and tolerability of nintedanib in patients with progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: data from the randomized controlled INBUILD trial. Respir Res 23:85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-01974-2

Wells AU, Flaherty KR, Brown KK, Inoue Y, Devaraj A, Richeldi L, Moua T, Crestani B, Wuyts WA, Stowasser S, Quaresma M, Goeldner RG, Schlenker-Herceg R, Kolb M; INBUILD trial investigators (2020) Nintedanib in patients with progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases-subgroup analyses by interstitial lung disease diagnosis in the INBUILD trial: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. Lancet Respir Med 8:453–460. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30036-9.

Matteson EL, Kelly C, Distler JHW, Hoffmann-Vold AM, Seibold JR, Mittoo S, Dellaripa PF, Aringer M, Pope J, Distler O, James A, Schlenker-Herceg R, Stowasser S, Quaresma M, Flaherty KR, INBUILD trial investigators (2022) Nintedanib in patients with autoimmune disease-related progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: subgroup analysis of the INBUILD trial. Arthritis Rheum 74:1039–1047. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.42075

Distler O, Highland KB, Gahlemann M, Azuma A, Fischer A, Mayes MD, Raghu G, Sauter W, Girard M, Alves M, Clerisme-Beaty E, Stowasser S, Tetzlaff K, Kuwana M, Maher TM, SENSCIS trial investigators (2019) Nintedanib for systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. N Engl J Med 380(26):2518–2528. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1903076

Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, Azuma A, Brown KK, Costabel U, Cottin V, Flaherty KR, Hansell DM, Inoue Y, Kim DS, Kolb M, Nicholson AG, Noble PW, Selman M, Taniguchi H, Brun M, Le Maulf F, Girard M et al (2014) Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 370:2071–2082. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1402584

Bonella F, Cottin V, Valenzuela C, Wijsenbeek M, Voss F, Rohr KB, Stowasser S, Maher TM (2022) Meta-analysis of effect of nintedanib on reducing FVC decline across interstitial lung diseases. Adv Ther 39:3392–3402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-022-02145-x

Selman M, Pardo A (2021) When things go wrong: exploring possible mechanisms driving the progressive fibrosis phenotype in interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir J 58(3):2004507. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.04507-2020

Brown KK, Martinez FJ, Walsh SLF, Thannickal VJ, Prasse A, Schlenker-Herceg R, Goeldner RG, Clerisme-Beaty E, Tetzlaff K, Cottin V, Wells AU (2020) The natural history of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir J 55:2000085. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00085-2020

Nasser M, Larrieu S, Si-Mohamed S, Ahmad K, Boussel L, Brevet M, Chalabreysse L, Fabre C, Marque S, Revel D, Thivolet-Bejui F, Traclet J, Zeghmar S, Maucort-Boulch D, Cottin V (2021) Progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease: a clinical cohort (the PROGRESS study). Eur Respir J 57:2002718. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02718-2020

Fu Q, Wang L, Li L, Li Y, Liu R, Zheng Y (2019) Risk factors for progression and prognosis of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: single center study with a large sample of Chinese population. Clin Rheumatol 38:1109–1116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-018-4382-x

Singh N, Varghese J, England BR, Solomon JJ, Michaud K, Mikuls TR, Healy HS, Kimpston EM, Schweizer ML (2019) Impact of the pattern of interstitial lung disease on mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 49:358–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.04.005

Wijsenbeek M, Cottin V (2020) Spectrum of fibrotic lung diseases. N Engl J Med 383:958–968. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2005230

Nambiar AM, Walker CM, Sparks JA (2021) Monitoring and management of fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: a narrative review for practicing clinicians. Ther Adv Respir Dis 15:17534666211039771. https://doi.org/10.1177/17534666211039771

Cylwik B, Chrostek L, Gindzienska-Sieskiewicz E, Sierakowski S, Szmitkowski M (2010) Relationship between serum acute-phase proteins and high disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Adv Med Sci 55:80–85. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10039-010-0006-7

Liu X, Mayes MD, Pedroza C, Draeger HT, Gonzalez EB, Harper BE, Reveille JD, Assassi S (2013) Does C-reactive protein predict the long-term progression of interstitial lung disease and survival in patients with early systemic sclerosis? Arthritis Care Res 65:1375–1380. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21968

Riemekasten G, Carreira PE, Saketkoo LA, Aringer M, Chung L, Pope J, Miede C, Stowasser S, Gahlemann M, Alves M, Khanna D (2020) Effects of nintedanib in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated ILD (SSc-ILD) and normal versus elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) at baseline: analyses from the SENSCIS trial. Ann Rheum Dis 79(Suppl.1):409

Collard HR, Ryerson CJ, Corte TJ, Jenkins G, Kondoh Y, Lederer DJ, Lee JS, Maher TM, Wells AU, Antoniou KM, Behr J, Brown KK, Cottin V, Flaherty KR, Fukuoka J, Hansell DM, Johkoh T, Kaminski N, Kim DS et al (2016) Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An international working group report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 194:265–275. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201604-0801CI

Hozumi H, Nakamura Y, Johkoh T, Sumikawa H, Colby TV, Kono M, Hashimoto D, Enomoto N, Fujisawa T, Inui N, Suda T, Chida K (2013) Acute exacerbation in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: a retrospective case control study. BMJ Open 3(9):e003132. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003132

Hozumi H, Kono M, Hasegawa H, Kato S, Inoue Y, Suzuki Y, Karayama M, Furuhashi K, Enomoto N, Fujisawa T, Inui N, Nakamura Y, Yokomura K, Nakamura H, Suda T (2022) Acute exacerbation of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: mortality and its prediction model. Respir Res 23:57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-01978-y

Izuka S, Yamashita H, Iba A, Takahashi Y, Kaneko H (2021) Acute exacerbation of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: clinical features and prognosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 60(5):2348–2354. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa608

Kamiya H, Panlaqui OM (2021) A systematic review of the incidence, risk factors and prognosis of acute exacerbation of systemic autoimmune disease-associated interstitial lung disease. BMC Pulm Med 21:150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-021-01502-w

Seibold JR, Maher TM, Highland KB, Assassi S, Azuma A, Hummers LK, Costabel U, von Wangenheim U, Kohlbrenner V, Gahlemann M, Alves M, Distler O, SENSCIS trial investigators (2020) Safety and tolerability of nintedanib in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease: data from the SENSCIS trial. Ann Rheum Dis 79:1478–1484. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217331

Corte T, Bonella F, Crestani B, Demedts MG, Richeldi L, Coeck C, Pelling K, Quaresma M, Lasky JA (2015) Safety, tolerability and appropriate use of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res 16:116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-015-0276-5

Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR, St Clair EW, Arayssi T, Carandang K, Deane KD, Genovese M, Huston KK, Kerr G, Kremer J, Nakamura MC, Russell LA, Singh JA, Smith BJ, Sparks JA, Venkatachalam S, Weinblatt ME, Al-Gibbawi M et al (2021) 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 73:924–939. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24596

Li L, Liu R, Zhang Y, Zhou J, Li Y, Xu Y, Gao S, Zheng Y (2020) A retrospective study on the predictive implications of clinical characteristics and therapeutic management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Clin Rheumatol 39:1457–1470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04846-1

Carrasco Cubero C, Chamizo Carmona E, Vela Casasempere P (2021) Systematic review of the impact of drugs on diffuse interstitial lung disease associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed) 17:504–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reumae.2020.04.010

Cottin V, Richeldi L, Rosas I, Otaola M, Song JW, Tomassetti S, Wijsenbeek M, Schmitz M, Coeck C, Stowasser S, Schlenker-Herceg R, Kolb M, INBUILD trial investigators (2021) Nintedanib and immunomodulatory therapies in progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Respir Res 22:84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-021-01668-1

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients who participated in the INBUILD trial.

Funding

The INBUILD trial was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH (BI). The authors did not receive payment for development of this manuscript. Writing assistance was provided by Elizabeth Ng and Wendy Morris of FleishmanHillard, London, UK, which was contracted and funded by BI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HM, LM, and MK contributed to the study conception and design. MK contributed to data collection. HM conducted the data analysis. All authors were involved in interpretation of the data and the writing and critical review of the manuscript. All authors and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The INBUILD trial was conducted in accordance with the protocol, the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Harmonised Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice from the International Conference on Harmonisation and was approved by local authorities.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before study entry.

Consent for publication

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Competing Interests

Eric L Matteson reports royalties from UpToDate; consulting fees from Alvotech and Boehringer Ingelheim (BI); fees for speaking from BI and Practice Point Communications; has participated on Data Safety Monitoring Boards or Advisory Boards for Horizon Therapeutics and the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS); has served on a Committee/Task Force for the American College of Rheumatology. Martin Aringer reports consulting fees for advisory boards and fees for lectures from BI and Roche. Gerd R Burmester reports consulting fees from and has served on speakers’ bureaus for AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, BI, Gilead, Lilly, Merck Sharpe and Dohme, Pfizer, Sanofi, Roche. Heiko Mueller and Lizette Moros are employees of BI. Martin Kolb reports research funding from BI, Pieris and Roche; consulting fees from AbbVie, Algernon, Bellerophon, BI, Cipla, CSL Behring, Horizon, LabCorp, Roche, ShouTi, United Therapeutics; fees for speaking from BI, Novartis, Roche; payment for expert testimony from Roche; has participated on Data Safety Monitoring Boards or Advisory Boards for LabCorp and United Therapeutics; and receives an allowance as Chief Editor of the European Respiratory Journal.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1.

(DOCX 245 kb)

(MP4 20280 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matteson, E.L., Aringer, M., Burmester, G.R. et al. Effect of nintedanib in patients with progressive pulmonary fibrosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: data from the INBUILD trial. Clin Rheumatol 42, 2311–2319 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-023-06623-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-023-06623-7