Abstract

The autoimmune rheumatic diseases have a clear predilection for women. Consequently, issues regarding family planning and pregnancy are a vital component of the management of these patients. Not only does pregnancy by itself causes physiologic/immunologic changes that impact disease activity but also women living with inflammatory arthritic conditions face the additional challenges of reduced fecundity and worsened pregnancy outcomes. Many women struggle to find adequate information to guide them on pregnancy planning, lactation and early parenting in relation to their chronic condition. This article discusses the gaps in the care provided to women living with inflammatory arthritis in standard practice and how a rheumatology nurse-led pregnancy clinic would fill such gap, consequently enhance the care provided and ensure appropriate education is provided to these individuals who represent the majority of the patients attending the rheumatology outpatient clinics. Such specialist care is expected to cover the whole journey as it is expected to provide high-quality care before, during and after pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autoimmune rheumatic diseases (ARDs), in particular systemic inflammatory rheumatic diseases which include rheumatoid arthritis [RA], systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], ankylosing spondyloarthritis [AS], antiphospholipid syndrome [APS] and systemic sclerosis, are lifelong, autoimmune systemic diseases more prevalent in women of childbearing age, who are diagnosed in their twenties and thirties, at a time in their life when marriage and family start to take centre stage [1]. The reported annual incidence of rheumatoid arthritis between the ages of 18 and 34 years has been stated to be 8.7 per 100,000. This figure rises further up to 36.2 per 100,000 between the ages of 35 and 44 years [2]. Also, the prevalence of SLE in women in their childbearing years is around 1 in 500. In concordance, the prevalence of psoriasis is approximately 2–3% with almost 50% of these patients being women, of which many are in their childbearing age as the average age of diagnosis is 28 years and approximately 75% of cases occur before the age of 40 [3, 4]. Having an understanding of the reproductive health-related problems and being able to address them is critical for health professionals engaged in their care. For women who live with a chronic disease like inflammatory arthritis, this usually joyful experience of planning for a family may raise a number of queries, uncertainties, challenges and negative thoughts. As a result, important decisions need to be taken when planning a family. This reaches further than their ability to conceive, to include queries about the heritability of the disease, ability to maintain successful pregnancy, effect on the foetus, outcome of the pregnancy as well as risks of the medication on their baby. There is a clear need for specialized support as psychological factors can play an important role and may include a sense of guilt, stigmatization and loneliness with self-concern about their physical and functional ability to be a mom and whether they will be able to look after their children and family as well as care for themselves.

New disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biologic therapy agents have shifted the management of inflammatory arthritis toward earlier, more aggressive therapy, with the ultimate goal of achieving full remission of the disease activity preventing structural joint damage. Alongside this, new treatment approaches, such as “treat to target”, have greatly improved treatment outcomes such as better functional ability and quality of life. These developments in the treatment paradigms have strengthened opinions that successful and safe pregnancies are possible, especially if pregnancy planning and screening for maternal and foetal risks are considered and implemented in standard practice, and the pregnancy takes place, while the disease is well controlled [5].

The introduction of specialized clinics for women with rheumatic conditions would enhance their care during pregnancy ensuring appropriate outcomes for both mothers and their baby. However, there has been an educational gap regarding how to set up such clinic. Based on our previous experience in setting up nurse-led early arthritis clinic [6], this service has adopted a similar approach, i.e. setting up a rheumatology nurse-led pregnancy clinic which would facilitate the provision of a holistic approach to both men and women in the childbearing period who would like to have a family. This article will present the unmet needs for such service, practical considerations in standard practice and targets and challenges that might face this model of care.

Why it is important to have a pregnancy clinic for arthritic patients

Although rheumatologists are exclusively qualified to manage women living with ARDs during pregnancy and are generally familiar with the teratogenic potential of certain antirheumatic medications commonly used in standard rheumatology practice, a survey carried out by Chakravarty et al. found only 56% of rheumatologists included in the survey noted that routine family planning counselling was given to reproductive age women [7]. This may be because some rheumatologists do not consider family planning to be a part of their clinical responsibilities or they may see this as a burden with other competing priorities which need addressing during clinic consultations. Some may consider themselves under qualified or feel uncomfortable with discussing reproductive health issues, and this might reflect inadequate training regarding ways to initiate conversations about family planning or with prescribing appropriate contraception. On the other hand, while primary care physicians and obstetrician-gynaecologists have greater experience with family planning, they may be unmindful of the fact that both contraceptives and pregnancy could be linked to a flare of the rheumatic disease activity or that certain antirheumatic medications may affect foetal development. A survey carried out by Toomey and Waldron [8] found that only 8% of the primary care physicians who shared in the study felt that they had the expertise to provide family planning for inflammatory bowel disease patients, and in 57% of cases, they deferred family planning matters to subspecialists. It has also been found that some providers believe that the responsibility for family planning and teratogenic medication risk counselling of rheumatic disease patients should fall to the rheumatologists [9].

While on one hand, there are several challenges to consider when planning setting up this service; on the other hand, there are several factors which highlight the unmet needs of this group of patients and the urgent necessity to set up these clinics. These include the following: (1) It is known that there are associated risks to both the mother and the foetus in pregnancy in women living with ARDs. (2) With proper planning and careful management of the disease, such risks can be minimized. (3) There is a need for joint collaboration between the specialist physicians who are involved in the patients’ care. (4) More open discussions should take place with patients about their plans for having a family which should be made a priority as well as discussing the potential complications of pregnancy. (5) Experienced rheumatologists or rheumatology nurse specialists would be the best people to tackle this challenge. Therefore, appropriate consideration of both the short- and long-term goals is vital to ensure favourable pregnancy outcomes for both the mothers and babies.

To simplify the proposed service, it will be split into 3 phases:

Planning for pregnancy: Patient-centred ethos

A range of family planning, pregnancy, and early parenting issues are raised in women of reproductive age who are affected by ARDs. [9]. Nearly half of pregnancies in Britain are not planned [Buyon et al., 2015]. This raises concerns in patients with ARDs as both the inflammatory condition as well as its treatments can cause problems with fertility, complications during pregnancy, disease activity and impact on contraceptive choices [10, 11]. Once diagnosed and as the patients, whether men or women, are being informed about the disease, its impact on their life, the approach to management and expected outcomes and their personal plans on the short and intermediate terms should also be discussed. Using a flexible narrative approach can encourage them to talk in their own words about their “lived experiences”, helping them to focus on what is important to them. It is likely that in their first visit, their main attention is on their arthritic condition. Later, as the arthritic condition is controlled, priority may shift to wanting to start or extend their family while on treatment. For this reason, regular assessment of the individual patient’s plans is important.

The stage of planning for pregnancy can be stratified into three different steps:

Planning the pregnancy

Identification in the clinic

Regular assessment at each clinic visit is needed to identify patients who are considering starting or extending their family. This can be accomplished by using one of the patients reported outcome measures surveys, which the patient can complete prior to each visit [12]. The role of PROMs has now expanded from the static phase, capturing and measuring outcomes at a single point of time, to a more dynamic role aimed at driving their improvement. This does not only evaluate the quality of the inflammatory arthritis care provided but also assess their current health status, comorbidity, motivation and health-related quality of life [6].

Family planning counselling

This is particularly important for women with rheumatic diseases. Among women with SLE, RA and the inflammatory myopathies, well-controlled disease at the time of conception has been associated with better outcomes (e.g. normal birth weight and term deliveries) [13, 14]. On the other hand, in these conditions, poorly controlled disease at conception increases the risk of intrauterine growth restriction, caesarean section, preeclampsia and/or foetal loss [11]. For women with SLE, intensive preconception counselling and disease management have led to reduced disease flares with live birth rates similar to the general population [15]. These findings show that family planning may improve pregnancy outcomes through facilitating disease control prior to conception, as well as helping women whose preference is to avoid pregnancy altogether [16, 17].

Contraception counselling

Patients living with ARDs should have individualized contraception counselling, with open discussion taking place to agree the treatment targets, prioritizing the patient’s desires and future plans. As the disease is usually active, in the early stages, the primary target would be to control the disease activity. When the disease passes into a state of remission, it is at this time that pregnancy may become the priority. Contraceptive counselling is an integral constituent of the patient’s management at a certain stage when pregnancy needs to be prevented. Healthcare professionals running the pregnancy clinic should be aware of the principle categories of contraceptive methods and their safety profiles. Research evaluating contraceptive safety has mostly focused on SLE, RA and APS, whereas most methods appear to be safe for other rheumatic diseases.

When selecting the contraceptive approach is considered, special attention should be paid to reversibility, safety, convenience, non-contraceptive benefits, side effects and costs. Also, it should be tailored to the individual woman's preference. Efficacy of the contraceptive method selected is of particular importance to those patients whose disease may flare or are at increased risk of developing complication during pregnancy. Talabi et al. [18] reviewed the efficacy and safety of contraceptive methods in ARDs patients. Based on their efficacy, contraceptive methods can be stratified into 3 categories summarized in Table 1.

An alternative may be emergency over the counter contraceptives, preventing pregnancy up to 5 days after unprotected sex, e.g. progestin-only contraceptives; however, it was reported that its efficacy wanes by the day. Therefore, other prescribed emergency contraceptive pills, particularly for over-weight women, may be more reliable in preventing pregnancy within 5-days of unprotected sex. Nevertheless, the most effective emergency contraceptive is a copper IUD placed within 7-days of unprotected sex [19].

Pregnancy

Fertility

A high degree of collaboration between the reproductive medicine specialist, high-risk obstetrician and rheumatologist is needed when addressing fertility issues in ARDs patients. Such collaboration between these specialities maximizes the potential for a successful outcome while, on the other hand, minimizing maternal risk.

Earlier studies have shown that women with polyarthritis such as RA and SLE tend to have smaller families than do control groups [24]. The Danish national birth cohort between 1996 and 2002 found that pregnant women enrolled in the cohort with prevalent RA (onset before conception) were more likely to have had treatment for infertility (9.8% vs 7.6%) or to have taken months to conceive (25.0% vs 15.6%) [25]. Out of 245 patients in the PARA study in the Netherlands which included women who were pregnant or attempting to become pregnant, 205 (84%) became pregnant, while 64 (31%) had a time to pregnancy over 12 months. This appears to be due to multifactorial aetiology including disease activity, the direct impact of such disorders on fertility and certain medication exposure including preconception use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and prednisone (> 7.5 mg/day) or cyclophosphamide in SLE patients which diminishes the ovarian reserve. Other data, in RA patients, showed that time to pregnancy was not found to be associated with rheumatoid factor (RF) or anti-citrullinated protein antibody status or disease duration [26].

Fertility preservation

Although the focus is on preservation of fertility by limiting use of cytotoxic medications when possible, in particular in SLE patients, and protecting the ovaries throughout cytotoxic therapy, this may be superseded by the need for prompt and effective treatment in severe disease. Cryopreservation of oocytes or embryos can be an effective option for preservation of fertility; however, this requires ovarian stimulation, and this might be impractical given the usual need to institute therapy quickly to prevent damage. There is also the risk of hyper stimulation in an already active SLE patient [27].

Assisted reproduction techniques

These techniques include ovarian induction (OI) with or without in vitro fertilization (IVF) and embryo transfer. These techniques raise particular concerns for SLE patients, as ovarian hyper stimulation syndrome (OHSS) is a complication of IVF which results in a diffuse capillary leak syndrome with pleural effusion and ascites. This raised issues of potential relevance for SLE patients [28, 29].

Managing disease course during pregnancy

Discussing the impact of pregnancy on disease activity is important as this forms a basis for treatment recommendation. The patient condition needs to be well controlled and stable for at least 3–6 months before conception. Pregnancy can impact on the disease course in different ways which vary from one disease to another. Improvement in RA disease activity during pregnancy has been documented [30, 31]. However, during pregnancy, there are limitations in using the conventional measures of disease activity assessment as these measures may be confounded by other pregnancy-related symptoms. A study comparing different disease activity scoring tools in RA versus healthy controls during pregnancy found that DAS28-CRP without assessment of global health was the preferred tool during pregnancy for measuring RA disease activity [32].

It has been demonstrated that when using disability measures such as health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) during pregnancy, these measures decrease in the third trimester in comparison to its outcome scored immediately before pregnancy. Interestingly assessment of the pain score over the course of pregnancy revealed that there has been significant improvement in the pain measure with 60% of the women reported improvement, whereas only 19% described worsening. However, only 16% of the patients reported remission during pregnancy (defined as no swollen joints and no use of medications) [31]. One study reported reduction of the DAS-28 during pregnancy, in spite of the fact that over one-third of women were not receiving any medications specific for RA in the third trimester [30].

In the postpartum setting, disease activity has been reported to get worse more often. This has been shown in assessing different parameters of disease activity including joint counts, pain measures, and DAS [31]. In the PARA cohort, 36% of women had a moderate flare and an additional 4% a severe flare [30].

In SLE, the risk of flare up of the disease activity during pregnancy is one of the major problems. Earlier studies revealed variable flare rates of flare ups which ranges between 25 and 65% [33, 34]. This disparity in the flare up of the disease activity during pregnancy extends to include variable responses at the different organ/systems level; e.g. musculoskeletal flares are less common, while renal and hematologic flares are more common. The majority of the flares in pregnancy are mild-to-moderate, with only small percentage of patients developing severe flares [34]. Predictors of disease flare which showed significant increase of flares risk in SLE women during the pregnancy include active disease during the 6 months prior to conception, history of lupus nephritis and discontinuation of antimalarial medication [35]. Table 2 shows a protocol for anti-natal monitoring the ARDs patients during pregnancy.

Pregnancy outcomes

It has been demonstrated across multiple cohorts and wide ranging geographical locations that delivery by caesarean section is more common among women with ARDs [36, 37]. Women who had moderate-to-high disease activity were more likely to have caesarean section in comparison to those who have low disease activity [38].

Increased risk of preeclampsia has been demonstrated in some studies among rheumatoid arthritis women [39]; however, this was not confirmed in other studies [40,41,42]. This variation of studies outcomes might be attributed to different patient populations or preeclampsia case ascertainment. In SLE patients, it might be difficult to differentiate between lupus nephritis flares and preeclampsia; as in both conditions, deteriorating renal function and increasing proteinuria, hypertension and thrombocytopenia may occur. Table 3 shows an approach to distinguish between the 2 problems. Investigation wise, a higher risk of preeclampsia and poor obstetric outcomes was associated with abnormal uterine artery waveforms [43,44,45].

Although several studies demonstrated an increased risk of preterm births [46, 47], this was not confirmed in other pregnancy outcomes research [35]. Interestingly, prematurity was associated with increased HAQ values during pregnancy. Variable data have been published regarding the impact of the disease on the infant weight. Low birth weight was reported in RA patients in some research, whereas other studies did not report this [48].

Medication Counselling

From pre conception, through pregnancy and following delivery, management decisions are complex due to the lack of data and the potential for teratogenicity of the therapies available. Standard and biologic disease-modifying medications, as well as corticosteroids in pregnancy, have been reviewed for their compatibility and safety [49]. For patients living with inflammatory arthritis, who are considering starting a family, their treating rheumatologist/ rheumatology nurse are the best source of information and support. Before considering getting pregnant, patients must be in remission, achieved by using DMARDs and biologics to control the disease activity. The aim should be to have an individualized treatment plan achieved by appropriate counselling regarding the risks and benefits of these medications optimizing the chance of a healthy pregnancy and baby.

Breastfeeding and postpartum care

Consideration needs to be given to the disease activity, the need for medication and the health benefits of breastfeeding when making a decision of whether or not to breastfeed. This decision should be made for each patient on an individual basis. Worse disease activity in first time breastfeeding women at 6 months postpartum was noted in a prospective study compared to non-breastfeeding women in the same time frame [50]. Prednisolone appears to be a suitable option for breastfeeding mothers who sustain a flare of their RA. The levels of prednisolone in breast milk reach 5–25% serum levels, with an estimated 0.1% of the mother’s dose being absorbed by the infant and insignificant amount compared to the endogenous production [51].

Both the BSR [49] and the American Academy of Paediatrics [52] advised that NSAIDs such as ibuprofen, diclofenac, indomethacin, naproxen and piroxicam are compatible with breastfeeding. A good option is ibuprofen due to its low rate of transfer, short half-life and low levels reached in breast milk [53]. The BSR has published a resource to help guide clinicians and patients regarding the safety of medications which can be used while breastfeeding [49].

Vaccination of the newborn

Given the fact that IgG antibodies are able to cross the placenta in the third trimester, with the exception of certolizumab, anti-TNF biologics have been found to be detectable in babies up to 6 months old of mothers treated with biologics [54]. Live attenuated vaccines should therefore be avoided based on this data, in babies up to 6 months old whose mothers have been exposed to biologics during the second half of pregnancy [55,56,57,58,59,60]. Although data is available regarding the lack of certolizumab transfer to cord blood, this is limited to a small number of patients. Also, no data regarding live vaccination of newborn of mothers treated with certolizumab has been published [61, 62].

The fatal case of a newborn, with disseminated tuberculosis exposed to infliximab, who was vaccinated with vaccinated with Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine, highlights the importance of avoiding live-attenuating vaccines during at least the first 6 months of life [63, 64]. EULAR suggests points to consider for using antirheumatic medications, before pregnancy, as well as during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Only babies exposed to biologics before 22 weeks can, according to standard protocols, receive vaccines including live vaccination. Although babies exposed to biologics during the second and third trimester can follow the vaccination programme, they should not receive live vaccines of the first 6 months of life. Measures of the biologic in question, in the child serum, may guide the decision as to whether or not give live vaccination [65].

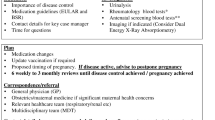

In conclusion, rheumatologists must lead family planning for women living with ARDs. A good option for patients to receive counselling and to be able to develop individualized care plans are rheumatology nurse-led pregnancy clinic. Such clinics can provide extensive monitoring and education, helping patients toward the best options for themselves and their newborn babies. Figure 1 shows a model of the rheumatology nurse-led pregnancy clinic service.

References

Wallenius M, Salvesen KA, Daltveit AK, Skomsvoll JF (2014) Rheumatoid arthritis and outcomes in first and subsequent births based on data from a national birth registry. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 93(3):302–307

Cauldwell M, Nelson-Piercy C (2012) Maternal and fetal complications of systemic lupus erythematosus. Obstet Gynaecol 14:167–174

Tauscher AE, Fleischer AB Jr, Phelps KC, Feldman SR (2002) Psoriasis and pregnancy. J Cutan Med Surg 6:561–570

Kurizky PS, Ferreira Cde C, Nogueira LS, Mota LM (2015) Treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis during pregnancy and breastfeeding. An Bras Dermatol 90(3):367–375

Al-Emadi S, Abutiban F, El Zorkany B, Ziade N, Al-Herz A, Al-Maini M (2016) Enhancing the care of women with rheumatic diseases during pregnancy: challenges and unmet needs in the Middle East. Clin Rheumatol 35:25–31

El Miedany Y (2013) PROMs in inflammatory arthritis: moving from static to dynamic. Clin Rheumatol 32:735–742

Chakravarty E, Clowse ME, Pushparajah DS, Mertens S, Gordon C (2014) Family planning and pregnancy issues for women with systemic inflammatory diseases: patient and physician perspectives. BMJ Open 4:e004081

Toomey D, Waldron B (2013) Family planning and inflammatory bowel disease: the patient and the practitioner. Fam Pract 30:64–68

Akers AY, Gold MA, Borrero S, Santucci A, Schwarz EB (2010) Providers’ perspectives on challenges to contraceptive coun-seling in primary care settings. J Women's Health 19:1163–1170

Vancsa A, Ponyi A, Constantin T, Zeher M, Danko K (2007) Pregnancy outcome in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Rheumatol Int 27:435–439

Ostensen M, Andreoli L, Brucato A, Cetin I, Chambers C, Clowse ME (2015) State of the art: reproduction and pregnancy in rheumatic diseases. Autoimmun Rev 14:376–386

El Miedany Y, Palmer D (2008) Can standard rheumatology clinical practice be patient-based? Br J Nurs 17(10):673–675

Buyon JP, Kim MY, Guerra MM, Laskin CA, Petri M, Lockshin MD (2015) Predictors of pregnancy outcomes in patients with lupus: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 163:153–163

Ngian GS, Briggs AM, Ackerman IN, Van Doornum S (2016) Management of pregnancy in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Med J Aust 204:62–63

Huong LD, Wechsler B, Vauthier-Brouzes D, Seebacher J, Lefebvre G, Bletry O (1997) Outcome of planned pregnancies in systemic lupus erythematosus: a prospective study on 62pregnancies. Br J Rheumatol 36:772–777

Soh MC, Nelson-Piercy C (2015) High-risk pregnancy and the rheumatologist. Rheumatology (Oxford) 54:572–587

Briggs AM, Jordan JE, Ackerman IN, Van Doornum S (2016) Establishing cross-discipline consensus on contraception, pregnancy and breast feeding-related educational messages and clinical practices to support women with rheumatoid arthritis: an Australian Delphi study. BMJ Open 6:e012139

Talabi M, Clowse M, Schwarz E, Callegar L, Morel L, Borrero OS (2018) Family planning counselling for women with rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Care Res 70(2):169–174

Curtis KM, Peipert JF (2017) Long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med 376:461–468

Lanza LL, McQuay LJ, Rothman KJ, Bone HG, Kaunitz AM, Harel Z (2013) Use of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception and incidence of bone fracture. Obstet Gynecol 121:593–600

Curtis KT, Tepper NK, Zapata L, Horton L, Jamieson DJ, Whiteman MK (2016) Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. MMWR Recomm Rep 65:1–103.23

Clowse ME, Chakravarty E, Costenbader KH, Chambers C, Michaud K (2012) Effects of infertility, pregnancy loss and patient concerns on family size of women with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res 64:668–674

Heit JA, Kobbervig CE, James AH, Petterson TM, BaileyKR MLJ III (2005) Trends in the incidence of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy or postpartum: a 30-year population-based study. Ann Intern Med 143:697–706

Bermas B, Sammaritano L (2015) Fertility and pregnancy in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Fertil Res Pract 1:13–18

Jawaheer D, Zhu JL, Nohr EA, Olsen J (2011) Time to pregnancy among women with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 63(6):1517–1521

Brouwer J, Hazes JM, Laven JS, Dolhain RJ (2015) Fertility in women with rheumatoid arthritis: influence of disease activity and medication. Ann Rheum Dis 74(10):1836–1841

Pasoto SG, Mendonca BB, Bonfa E (2002) Menstrual disturbances in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus without alkylating therapy: clinical hormonal and therapeutic associations. Lupus 11:175–180

Guballa N, Sammaritano L, Schwartzman S, Buyon J, Lockshin MD (2000) Ovulation induction and in vitro fertilization in systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 43:550–556

Huong DL, Wechsler B, Vauthier-Brouzes D, Duhat P, Costedoat N, Lefebre G (2002) Importance of planning ovulation induction therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome: a single center retrospective study of 21 cases and 114 cycles. Sem Arthritis Rheum 32(3):174–188

de Man YA, Dolhain RJ, van de Geijn FE, Willemsen SP, Hazes JM (2008) Disease activity of rheumatoid arthritis during pregnancy: results from a nationwide prospective study. Arthritis Rheum 59(9):1241–1248

Barrett JH, Brennan P, Fiddler M, Silman AJ (1999) Does rheumatoid arthritis remit during pregnancy and relapse postpartum? Results from a nationwide study in the United Kingdom performed prospectively from late pregnancy. Arthritis Rheum 42(6):1219–1227

de Man YA, Hazes JM, van de Geijn FE, Krommenhoek C, Dolhain RJ (2007) Measuring disease activity and functionality during pregnancy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 57(5):716–722

Carvalheiras G, Vita P, Marta S, Trovao R, Farinha F, Braga J, Rocha G, Almeida I, Marinho A, Mendonca T (2010) Pregnancy and systemic lupus erythematosus: review of clinical features and outcome of 51 pregnancies at a single institution. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 38(2–3):302–306

Ruiz-Irastorza G, Lima F, Alves J, Khamashta MA, Simpson J, Hughes GR, Buchanan NM (1996) Increased rate of lupus flare during pregnancy and the puerperium: a prospective study of 78 pregnancies. Br J Rheumatol 35(2):133–138

Clowse ME, Magder LS, Witter F, Petri M (2005) The impact of increased lupus activity on obstetric outcomes. Arthritis Rheum 52(2):514–521

Nørgaard M, Larsson H, Pedersen L (2010) Rheumatoid arthritis and birth outcomes: a Danish and Swedish nationwide prevalence study. J Intern Med 268(4):329–337

Wallenius M, Skomsvoll JF, Irgens LM (2011) Pregnancy and delivery in women with chronic inflammatory arthritides with a specific focus on first birth. Arthritis Rheum 63(6):1534–1542

de Man YA, Hazes JM, van der Heide H et al (2009) Association of higher rheumatoid arthritis disease activity during pregnancy with lower birth weight: results of a national prospective study. Arthritis Rheum 60(11):3196–3206

Cortes-Hernandez J, Ordi-Ros J, Paredes F, Casellas M, Castillo F, Vilardell-Tarres M (2002) Clinical predictors of fetal and maternal outcome in systemic lupus erythematosus: a prospective study of 103 pregnancies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 41(6):643–650

Clark CA, Spitzer KA, Laskin CA (2005) Decrease in pregnancy loss rates in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus over a 40-year period. J Rheumatol 32(9):1709–1712

Gladman DD, Tandon A, Ibanez D, Urowitz MB (2010) The effect of lupus nephritis on pregnancy outcome and fetal and maternal complications. J Rheumatol 37(4):754–758

Clowse ME, Magder L, Witter F, Petri M (2006) Hydroxychloroquine in lupus pregnancy. Arthritis Rheum 54(11):3640–3647

Cnossen JS, Morris RK, ter Riet G, Mol BW, van der Post JA, Coomarasamy A, Zwinderman AH, Robson SC, Bindels PJ, Kleijnen J et al (2008) Use of uterine artery Doppler ultrasonography to predict pre-eclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction: a systematic review and bivariable meta-analysis. CMAJ 178(6):701–711

Huong LTD, Wechsler B, Vauthier-Brouzes D, Duhaut P, Costedoat N, Andreu MR, Lefebvre G, Piette JC (2006) The second trimester Doppler ultrasound examination is the best predictor of late pregnancy outcome in systemic lupus erythematosus and/or the antiphospholipid syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 45(3):332–338

Lateef A, Petri M (2013) Managing lupus patients during pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 27(3):435–447

Reed SD, Vollan TA, Svec MA (2006) Pregnancy outcomes in women with rheumatoid arthritis in Washington state. Matern Child Health J 10(4):361–366

Rom AL, Wu CS, Olsen J (2014) Fetal growth and preterm birth in children exposed to maternal or paternal rheumatoid arthritis: a nationwide cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol 66(12):3265–3273

Krause M, Makol A (2016) Management of rheumatoid arthritis during pregnancy: challenges and solutions. Rheumatol Res Rev 8:23–36

Flint J, Panchal S, Hurrell A, van de Venne M, Gayed M (2016) BSR and BHPR guideline on prescribing drugs in pregnancy and breastfeeding—part I: standard and biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and corticosteroids. Rheumatology 55:16931697

Barrett JH, Brennan P, Fiddler M, Silman A (2000) Breast-feeding and postpartum relapse in women with rheumatoid and inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 43(5):1010

Ost L, Wettrell G, Björkhem I, Rane A (1985) Prednisolone excretion in human milk. J Pediatr 106(6):1008–1011

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs (2001) Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics 108(3):776–789

Ling J, Koren G (2016) Challenges in vaccinating infants born to mothers taking immunoglobulin biologicals during pregnancy. Expert Rev Vaccines 15:239–256

Julsgaard M, Christensen LA, Gibson PR, Gearry RB, Fallingborg J, Hvas CL, Bibby BM, Uldbjerg N, Connell WR, Rosella O, Grosen A, Brown SJ, Kjeldsen J, Wildt S, Svenningsen L, Sparrow MP, Walsh A, Connor SJ, Radford-Smith G, Lawrance IC, Andrews JM, Ellard K, Bell SJ (2016) Concentrations of Adalimumab and infliximab in mothers and newborns, and effects on infection. Gastroenterology 151:110–119

Mahadevan U, Wolf DC, Dubinsky M (2013) Placental transfer of anti-tumor necrosis factor agents in pregnant patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 11:286–292

Zelinkova Z, de Haar C, de Ridder L (2011) High intra-uterine exposure to infliximab following maternal anti-TNF treatment during pregnancy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 33:1053–1058

Murashima A, Watanabe N, Ozawa N (2009) Etanercept during pregnancy and lactation in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis: drug levels in maternal serum, cord blood, breast milk and the infant’s serum. Ann Rheum Dis 68:1793–1794

Berthelsen BG, Fjeldsøe-Nielsen H, Nielsen CT (2010) Etanercept concentrations in maternal serum, umbilical cord serum, breast milk and child serum during breastfeeding. Rheumatology 49:2225–2227

Friedrichs B, Tiemann M, Salwender H (2006) The effects of rituximab treatment during pregnancy on a neonate. Haematologica 91:1426–1427

Mahadevan U, Cucchiara S, Hyams JS (2011) The London position statement of the world congress of gastroenterology on biological therapy for IBD with the European Crohn’s and colitis organisation: pregnancy and pediatrics. Am J Gastroenterol 106:214–223

Mariette X, Förger F, Abraham B (2018) Lack of placental transfer of certolizumab pegol during pregnancy: results from CRIB, a prospective, postmarketing, pharmacokinetic study. Ann Rheum Dis 77:228–233

Förger F, Zbinden A, Villiger PM (2016) Certolizumab treatment during late pregnancy in patients with rheumatic diseases: low drug levels in cord blood but possible risk for maternal infections. A case series of 13 patients. Joint Bone Spine 83:341–343

Cheent K, Nolan J, Shariq S et al (2010) Case report: fatal case of disseminated BCG infection in an infant born to a mother taking infliximab for Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis 4:603–605

Gisbert JP, Chaparro M (2013) Safety of anti-TNF agents during pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 108:1426–1438

Götestam Skorpen C, Hoeltzenbein M, Tincani A (2016) The EULAR points to consider for use of antirheumatic drugs before pregnancy, and during pregnancy and lactation. Ann Rheum Dis 75:795–810

Funding

This article was made Open Access with the financial support of King’s College London.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El Miedany, Y., Palmer, D. Rheumatology-led pregnancy clinic: enhancing the care of women with rheumatic diseases during pregnancy. Clin Rheumatol 39, 3593–3601 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05173-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05173-6