Abstract

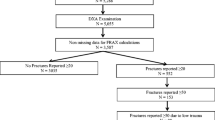

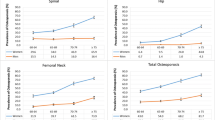

Current Canadian osteoporosis guidelines recommend routine bone density screening of men at age 65. The purpose of this study is to determine the prevalence of osteoporosis in men aged 65–75 in after application of screening guidelines. All males aged 65–75 years who attended a large primary care clinic were advised of the 2010 Canadian osteoporosis guidelines and advised to obtain a bone density scan at or after their 65th birthday. Those who did not have a bone density scan since their 65th birthday were advised to obtain a scan, unless there was obvious reason not to do so (i.e. known osteoporosis). A record of the results for each patient were kept and tallied to determine the prevalence of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis was defined as a T-score of ≤ −2.5 in either the hip or lumbar spine. Of 574 male subjects in this clinic, between the ages of 65-75, 557 had a bone density scan, either already having done so at the time of being informed of the guidelines or obtaining a scan in the subsequent year after being informed of the guidelines. The prevalence of osteoporosis was 1.6 % (9/557, 95 % confidence interval 0.8–3.1 %) in this sample. The average age of subjects with osteoporosis was 70.5 ± 1.4 years (range 68–75). None of the subjects under 68 years of age were found to have osteoporosis. The prevalence of osteoporosis in unselected male cohorts aged 65 may be too low to justify the routine bone density screening recommended in the 2010 Canadian osteoporosis guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Binkley N, Bilezikian JP, Kendler DL, Leib ES, Lewiecki EM, Petak SM (2006) Official positions of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry and executive summary of the 2005 Position Development Conference. J Clin Densitom 9:4–14

Alexandra Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, Atkinson S, Brown JP et al (2010) 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ 182:1864–1873

Jones G, Nguyen T, Sambrook PN, Kelly PJ, Gilbert C, Eisman JA (1994) Symptomatic fracture incidence in elderly men and women: the Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study (DOES). Osteoporos Int 4:277–282

Mussolino ME, Looker AC, Madans JH, Langlois JA, Orwoll ES (1998) Risk factors for hip fracture in white men: the NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. J Bone Miner Res 13:918–924

Kellie SE, Brody JA (1990) Sex-specific and race-specific hip fracture rates. Am J Public Health 80:326–328

Papadimitropoulos EA, Coyte PC, Josse RG, Greenwood CE (1997) Current and projected rates of hip fracture in Canada. CMAJ 157:1357–1363

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B, Oglesby AK (2003) The components of excess mortality after hip fracture. Bone 32:468–473

Trombetti A, Herrmann F, Hoffmeyer P, Schurch MA, Bonjour JP, Rizzoli R (2002) Survival and potential years of life lost after hip fracture in men and age-matched women. Osteoporos Int 13:731–737

Jacobsen SJ, Goldberg J, Miles TP, Brody JA, Stiers W, Rimm AA (1992) Race and sex differences in mortality following fracture of the hip. Am J Public Health 82:1147–1150

O’Neill TW, Felsenberg D, Varlow J, Cooper C, Kanis JA, Silman AJ (1996) The prevalence of vertebral deformity in European men and women: the European Vertebral Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res 11:1010–1018

Jackson SA, Tenenhouse A, Robertson L (2000) Vertebral fracture definition from population-based data: preliminary results from the Canadian Multicenter Osteoporosis Study (CaMos). Osteoporos Int 11:680–687

Hasserius R, Johnell O, Nilsson BE et al (2003) Hip fracture patients have more vertebral deformities than subjects in population-based studies. Bone 32:180–184

Hasserius R, Karlsson MK, Nilsson BE, Redlund-Johnell I, Johnell O (2003) Prevalent vertebral deformities predict increased mortality and increased fracture rate in both men and women: a 10-year population-based study of 598 individuals from the Swedish cohort in the European Vertebral Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int 14:61–68

Borgstrom F, Zethraeus N, Johnell O et al (2006) Costs and quality of life associated with osteoporosis related fractures in Sweden. Osteoporos Int 17:637–650

Schousboe JT, Taylor BC, Fink HA, Kane RL, Cummings SR et al (2007) Cost-effectiveness of bone densitometry followed by treatment of osteoporosis in older men. JAMA 298:629–637

Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL et al (1998) Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int 8:468–489

Cass AR, Shepherd AJ (2013) Validation of the Male Osteoporosis Risk Estimation Score (MORES) in a primary care setting. J Am Board Fam Med 26(4):436–444

Bertakis KD, Azari R, Helms LJ, Callahan EJ, Robbins JA (2000) Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. J Fam Pract 49(2):147–152

http://www.tobaccoreport.ca/2013/TobaccoUseinCanada_2013.pdf

http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-625-x/2010001/article/11091-eng.htm

Sawka AM, Papaioannou A, Josse RG, Murray TM, Ioannidis G et al (2006) What is the number of older Canadians needed to screen by measurement of bone density to detect an undiagnosed case of osteoporosis? A population-based study from CaMos. J Clin Densitom 9(4):413–418

Disclosures

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferrari, R. Prevalence of osteoporosis in men aged 65–75 in a primary care setting. A practice audit after application of the Canadian 2010 guidelines for osteoporosis screening. Clin Rheumatol 34, 523–527 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-014-2642-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-014-2642-y