Abstract

Weathered basement aquifers are vital sources of drinking water in Africa. In order to better understand their role in the urban water balance, in a weathered basement aquifer in Kampala, Uganda, this study installed a transect of monitoring piezometers, carried out spring flow and high-frequency groundwater level monitoring, slug tests and hydrochemical analyses, including stable isotopes and groundwater residence time indicators. Findings showed a typical weathered basement aquifer with a 20–50-m thickness. Groundwater recharge was 3–50 mm/year, occurring during sustained rainfall. Recharge to a deep groundwater system within the saprock was slow and prolonged, while recharge to the springs on the valley slopes was quick and episodic, responding rapidly to precipitation. Springs discharged shallow groundwater, mixed with wastewater infiltrating from onsite sanitation practices and contributions from the deeper aquifer and were characterised by low flow rates (< 0.001 m3/s), low pH (<5), high nitrate values (61–190 mg/L as NO3), and residence times of <30 years. The deeper groundwater system occurred in the saprolite/saprock, had low transmissivity (< 1 × 10−5 m2/s), lower nitrate values (<20 mg/L as NO3), pH 6–6.5 and longer residence times (40–60 years). Confined groundwater conditions in the valleys were created by the presence of clay-rich alluvium and gave rise to artesian conditions where groundwater had lower nitrate concentrations. The findings provide new insights into weathered basement aquifers in the urban tropics and show that small-scale abstractions are more sustainable in the deeper groundwater system in the valleys, where confined conditions are present.

Résumé

Les aquifères de socle altéré constituent des sources d’eau potable vitales en Afrique. Afin de mieux comprendre leur rôle dans le bilan en eau en contexte urbain, cette étude sur un aquifère de socle altéré à Kampala, Ouganda, se base sur la mise en place d’un transect de piézomètres, le suivi du débit de sources et des niveaux d’eau souterraine haute fréquence ainsi que la réalisation de slug tests et d’analyses hydrochimiques, incluant les isotopes stables et des indicateurs du temps de résidence de l’eau souterraine. Les résultats montrent un aquifère de socle altéré typique avec une épaisseur de 20 à 50 m. La recharge est estimée à 3–50 mm/an, se produisant pendant les épisodes de pluie soutenue. La recharge d’un système aquifère profond dans le socle rocheux fracturé avec altération limitée aux fractures – saprock - est lente et prolongée, alors que la recharge sur les pentes de vallée drainées par les sources est rapide et épisodique, avec une réponse rapide aux précipitations. Les sources drainent l’eau de l’aquifère superficiel, mélangée avec de l’eau usée s’infiltrant depuis des systèmes d’assainissement in situ et une contribution de l’aquifère profond; elles se caractérisent par des débits faibles (<0.001 m3/s), un pH faible (<5), des concentrations élevées en nitrate (61–190 mg/L NO3) et des temps de résidence >30 ans. Le système aquifère plus profond est situé dans la saprolite/saprock; il montre une faible transmissivité (< 1 × 10−5 m2/s), des concentrations faibles en nitrate (<20 mg/L NO3), un pH de 6–6.5 et des temps de résidence plus longs (40–60 ans). La captivité de l’aquifère dans les vallées est due à la présence d’alluvions riches en argile et conduit à des conditions artésiennes où l’eau souterraine montre de faibles concentrations en nitrate. Les résultats fournissent de nouvelles perspectives sur les aquifères de socle altéré en contexte tropical urbain et montrent que des prélèvements à l’échelle locale sont plus durables sur le système aquifère plus profond dans les vallées, où des conditions captives sont présentes.

Resumen

Los acuíferos en basamentos meteorizados son fuentes esenciales de agua potable en África. Para comprender mejor su papel en el balance hídrico urbano, en un acuífero de basamento meteorizado de Kampala (Uganda), este estudio instaló una transecta de piezómetros de control, llevó a cabo un seguimiento del flujo de los manantiales y del nivel de las aguas subterráneas en alta frecuencia, slug tests y análisis hidroquímicos, incluyendo isótopos estables e indicadores del tiempo de residencia de las aguas subterráneas. Los resultados mostraron un típico acuífero de basamento meteorizado con un espesor de 20–50 m. La recarga de las aguas subterráneas era de 3–50 mm/año, y se producía durante las lluvias persistentes. La recarga de un sistema de aguas subterráneas profundas dentro del saprolito era lenta y prolongada, mientras que la recarga de los manantiales en las laderas del valle era rápida y episódica, respondiendo rápidamente a las precipitaciones. Los manantiales descargaban aguas subterráneas poco profundas, mezcladas con aguas residuales infiltradas procedentes de las prácticas de saneamiento in situ y con aportaciones del acuífero más profundo, y se caracterizaban por sus bajos caudales (<0.001 m3/s), su bajo pH (<5), sus altos valores de nitrato (61–190 mg/L como NO3) y sus tiempos de residencia de < 30 años. El sistema de aguas subterráneas más profundas se produjo en el saprolito, tenía una baja transmisividad (< 1 × 10−5 m2/s), valores de nitrato más bajos (<20 mg/L como NO3), pH 6–6.5 y tiempos de residencia más largos (40–60 años). Las condiciones de confinamiento de las aguas subterráneas en los valles fueron creadas por la presencia de aluviones ricos en arcilla y dieron lugar a condiciones artesianas en las que las aguas subterráneas tenían menores concentraciones de nitrato. Los resultados aportan nuevos conocimientos sobre los acuíferos de basamento meteorizado en los territorios urbanos tropicales y muestran que las extracciones a pequeña escala son más sostenibles en el sistema de aguas subterráneas más profundas de los valles, donde se dan las condiciones de confinamiento.

摘要

风化基岩含水层是非洲重要的饮用水源。为了更好地了解它们在城市水平衡中的作用, 研究在乌干达坎帕拉某风化基岩含水层中安装了一段监测压力计, 进行了泉水和高频地下水位监测、栓塞试验和水化学分析, 包括稳定同位素和地下水滞留时间指标。调查结果显示了厚度为 20–50 m的典型风化基岩含水层。持续降雨期间的地下水补给量为 3–50 mm/year。岩层内深层地下水系统的补给缓慢而呈现持久性, 而山谷坡上的泉水补给快速且呈现间歇性, 对降水反应迅速。在地下水浅埋区排泄成泉水, 与现场卫生措施渗入的废水和深层含水层混合, 具有低流速(< 0.001 m3/s)、低 pH 值(< 5)、高硝酸盐值(61–190 mg/L)、滞留时间 <30 年。较深的地下水系统分布在腐泥土/树岩中, 具有低渗透率(< 1 × 10−5 m2/s)、较低的硝酸盐值(<20 mg/L)、pH 6–6.5 和较长的滞留时间(40–60 年)。山谷中承压的地下水是由富含粘土的冲积层造成的, 并导致地下水较低硝酸盐浓度的自流条件。研究结果为城市热带地区风化基岩含水层提供了新的见解, 并表明在存在承压条件的山谷的较深地下水系统中, 小规模开采地下水更具可持续性。

Resumo

Aquíferos em rochas de embasamento alterado são fontes vitais de água potável na África. A fim de melhor compreender seu papel no balanço hídrico urbano, em um aquífero de embasamento alterado em Kampala, Uganda, este estudo instalou uma transecção de piezômetros, monitorou com alta frequência fluxo de nascentes e nível das águas subterrâneas, realizou testes de condutividade hidráulica (slug) e análises hidroquímicas, incluindo isótopos estáveis e indicadores de tempo de residência das águas subterrâneas. Os resultados indicaram um típico aquífero de embasamento alterado, com 20–50 m de espessura. A recarga da água subterrânea é de 3–50 mm/ano, ocorrendo durante o período de chuvas. A recarga do sistema aquífero profundo dentro da rocha de alteração era lenta e prolongada, enquanto a recarga de nascentes nas encostas dos vales era rápida e episódica, respondendo prontamente à precipitação. As nascentes descarregam águas subterrâneas rasas, misturadas com águas residuais infiltradas a partir da rede de saneamento local e contribuições do aquífero profundo, e foram caracterizadas por baixas vazões (< 0.001 m3/s), baixo pH (<5), altas concentrações de nitrato (61–190 mg/L de NO3), e tempo de residência <30 anos. O sistema aquífero mais profundo ocorre no saprolito/rocha de alteração, tem baixa transmissividade (< 1 × 10−5 m2/s), concentrações de nitrato mais baixas (<20 mg/L de NO3), pH 6–6.5, e maior tempo de residência (40–60 anos). Condições de confinamento de água subterrânea nos vales foram criadas pela presença de aluvião rico em argila, gerando condições de artesianismo em que a água subterrânea tinha menores concentrações de nitrato. Os resultados fornecem novas percepções sobre os aquíferos de embasamento alterado em áreas urbanas tropicais e mostram que abstrações de pequena escala são mais sustentáveis no sistema aquífero profundo nos vales, em que ocorrem condições de confinamento.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

From 1990 to 2018, the urban population in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) grew from 135 to 423 million (UN-DESA 2019), while the percentage of the population living in urban informal settlements or slums remained constant at around 55–60%. By 2050, in SSA, it is predicted that there will be 1.25 billion people living in urban areas of which 723 million people will live in slums (UN-DESA 2019). This growth will continue to lead to a rise in the demand for potable water (Carter and Parker 2009; Foster and Sage 2017; Parnell and Walawege 2011; Taylor et al. 2004). In many situations, water supply in these areas is met by groundwater self-supply (e.g. Silva et al. 2020; Sutton and Butterworth 2021) from protected springs, shallow wells and deep boreholes (Carter and Parker 2009; Gaye and Tindimugaya 2019; Grönwall 2016; Komakech and de Bont 2018; Lutterodt et al. 2018; MacDonald et al. 2012; Okotto et al. 2015; Okotto-Okotto et al. 2015; Olago 2019; Taylor and Barrett 1999; WaterAid 2010).

In Kampala, Uganda, groundwater is an important part of the urban water cycle, not only for water supply (Flynn et al. 2012; Howard et al. 2003; Kulabako et al. 2007, 2008, 2010; Nabasirye et al. 2011; Nastar et al. 2019; Silvestri et al. 2018), but also in relation to on-site sanitation and wastewater infiltration to groundwater (Fuhrimann et al. 2016; Katukiza et al. 2015; Katukiza et al. 2014; Lutterodt et al. 2014; Lutterodt et al. 2012; Ronoh et al. 2020; Sakomoto et al. 2020; Tumwebaze et al. 2019), and groundwater input to wetlands in and around the city (e.g. Kansiime et al. 2007; Kyambadde et al. 2004; Nyenje et al. 2014a; Were et al. 2021, 2020). The hydrogeology and flow systems of the uppermost 2–3 m of the subsurface in some of the lowland parts of Kampala (Bwaise) has been studied in some detail (Kulabako et al. 2007; Nyenje et al. 2013, 2014a). Although, the hydrogeology (i.e. evolution, texture and hydraulic properties) of the deeper weathered basement has also been studied (see Guma et al. 2019; Taylor and Howard 1999, 2000), there is still limited understanding of its linkage with groundwater flow systems and the rest of the urban water cycle.

Crystalline basement rocks with a thick mantle of in situ weathered material underlie approximately 34% of Africa’s land surface (Bianchi et al. 2020; Macdonald et al. 2008, 2012; MacDonald and Calow 2009, Lachassagne et al. 2011; Taylor and Howard 1998; Vouillamoz et al. 2005; Wright 1992). The established hydrogeological conceptual model of the weathered profile of crystalline basement rocks in tropical Africa includes (Bianchi et al. 2020): a few meters of residual soil (RS) that often comprise ferralitic soils with laterite pisoliths; an upper saprolite (US) layer composed of mainly secondary clay minerals, with thicknesses ranging from a few to tens of meters; a lower saprolite (LS) layer, similar to the US in thickness but with a much higher proportion of primary minerals; and a fractured layer, up to tens of meters thick, referred to as the saprock (SR), transitioning with depth into the underlying unweathered basement rock (Acworth 1981; Chilton and Foster 1995; Dewandel et al. 2006; Jones 1985; Wyns et al. 2004; Dewandel et al. 2006; Maréchal et al. 2004; Courtois et al. 2010; Lachassagne et al. 2011, 2014, 2021; Belle et al. 2019; Alle et al. 2018; Bianchi et al. 2020). The residual soil and saprolite layers form a largely unconsolidated part of the profile, also known as the regolith (Bianchi et al. 2020). While the fissures are often assumed to be the result of tectonic or lithostatic decompression processes, it has also been suggested that they are related to the weathering process with the degradation of bedrock driven by the swelling of minerals such as biotite (Lachassagne et al. 2011). The fissured and fractured saprock typically represents the most transmissive zone within the weathering profile (Lachassagne 2008).

Basement aquifers (or hard-rock aquifers) are therefore able to develop within the weathered overburden and the fractured/fissured bedrock of crystalline rocks and usually occupy the first tens of metres below ground surface (Taylor and Howard 2000; Wright 1992). They are widespread in Africa and are important sources of drinking water in both urban and rural areas (Alle et al. 2018; Belle et al. 2019; Mukherjee et al. 2008; Wright 1992). These aquifers are typically low yielding and are mainly utilised for hand pumped boreholes (Alle et al. 2018. MacDonald et al. 2012; Taylor and Howard 2000; Vouillamoz et al. 2014). Well failures are reported to be very high (10–50%; Wright and Burgess 1992) and most especially in West Africa (Alle et al. 2018). Recent research has focused on conceptualising the hydrogeological functioning of these aquifers using various techniques such as geophysical surveys and hydrological tracers in order to inform future sustainable use of these aquifers (e.g. Courtois et al. 2010; Dewandel et al. 2006; Lachassagne et al. 2021; Taylor and Howard 2000; Wyns et al. 2004).

Basement aquifers are highly heterogeneous and complex and need to be characterised and quantified more effectively at a local and regional level for proper groundwater management (Bonsor et al. 2014; Cuthbert et al. 2019; Lachassagne 2008; Lapworth et al. 2017; Gaye and Tindimugaya 2019; Stone et al. 2019; Wright 1992). This report presents the findings of a detailed data-driven investigation of the hydrogeology of the top 50 m of a highly weathered granite-gneiss complex situated in an urban context in Kampala, Uganda. The specific aim of this report was to characterise groundwater flow, chemistry, age, and recharge along a flow transect in order to strengthen the conceptual hydrogeological understanding with a view to assessing the sustainability and response of basement aquifer systems to potential future changes in climate and abstraction. This is of wide relevance to many parts of Africa, and elsewhere on weathered basement terrains, which are witnessing a rapid expansion of urban centres in hard-rock settings and a growing demand for water resources.

Study area and hydrogeology

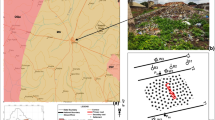

The study area is a section of Lubigi catchment in Kampala, the capital city of Uganda, comprising the wards of Kasubi, Makerere, Nabweru, and Bwaise (Fig. 1). It is a typical peri-urban setting situated about 3 km south west of the city centre (0.31962°N, 32.581°E). The wards in the study area are largely informal settlements, with low-income residents, and they are unsewered and rely on pit latrines and septic tanks as the main forms of sanitation (Katukiza et al. 2010). The settlement density is high with approximately 27,000 inhabitants per square kilometre (UBOS 2014). In these areas, springs discharging groundwater in the valleys are a major source of water supply, besides the municipal piped water supplied mainly from Lake Victoria (Howard et al. 2003; Kulabako et al. 2007; Lutterodt et al. 2014; Nsubuga et al. 2004). The municipal water supply system operated by the National Water and Sewerage Cooperation (NWSC) is a large pipe network serving about 80% of the population in Kampala city (Murungi and Blokland 2016; Van Dijk 2016). The service is, however, highly unreliable and costly and most residents especially in informal settlements still rely on groundwater from springs as an alternative source of water. Previous studies show that shallow groundwater which supplies springs in the study area is heavily contaminated with high levels of faecal coliforms (in 97% of the sources), nitrate (up to 136 mg/L) and low pH (<5) (Howard et al. 2003; Kulabako et al. 2007; Lutterodt et al. 2014; Nsubuga et al. 2004; Nyenje et al. 2010, 2014b). This contamination is attributed to infiltration of wastewater onsite from sanitation facilities like pit latrines to the shallow groundwater.

a Location of the study area in Kampala city, Uganda; b Geology of Kampala (Westerhof et al. 2014) including aquifer transmissivities from sites in Kampala; c Study area details close to Makerere University and Bwaise showing water level monitoring and sampling locations

The Lubigi catchment where the study area is located is one of the five drainage systems in Kampala city, located in the north-western part of the city. It is a typical peri-urban catchment with a number of low-income informal settlements and small agriculture and livestock keeping at household level. The catchment is primarily drained by the Nsooba channel and a number of secondary and tertiary drains which drain into the Lubigi wetland. The Lubigi wetland drains northwards into the Mayanja River and finally to Lake Kyoga which is part of the River Nile flow regime. Like many parts of Kampala, the catchment is characterised by hills and low-lying swamp-filled valleys with elevation varying from 1154 and 1306 m above sea level.

The area experiences a humid tropical climate with two rain seasons (March–May and September–December) with a mean annual rainfall of 1,450 mm/year and evapotranspiration of about 1,151 mm/year (Nyenje et al. 2010). The regional climate is highly influenced by the Inter-tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), whereas the Lake Victoria system dictates local rainfall variability (Maidment et al. 2013).

The underlying geology in the study area is dominated by Precambrian basement rocks consisting of granite-gneiss of the Kampala suite with some metasedimentary rocks of Palaeoproterozoic age consisting of primarily slate, phyllite, mica schist and metasandstone (Taylor and Howard 1999; Westerhof et al. 2014). Basement rocks are almost entirely overlain by a weathered, lateritic regolith (≈30 m) dominated by kaolinite and quartz minerals, with minor amounts of crystalline iron oxide (Flynn et al. 2012; Taylor and Howard 1999). The regolith throughout much of the Cenozoic era has been dissected by fluvial processes to leave a distinctive landscape of low conical- or ridge-like hills separated by broad, swamp-filled valleys—see Fig. S2 (terrain model for Kampala) in the electronic supplementary material (ESM). The elevation difference between valley floors and hill tops is typically in the range 50–250 m, which approximates to the maximum thickness of weathered regolith. Hills are mostly composed of in situ saprolite, locally capped by a layer of indurated ferricrete that represents deep basement weathering in the late Mesozoic and early Cenozoic (Taylor and Howard 1998). The regolith has sufficient permeability to yield small water supplies that serve a few boreholes and a number of springs located in the valleys (Barrett et al. 1999; Flynn et al. 2012; Taylor and Howard 1996, 1998); thus, shallow groundwater flow systems that supply springs exist in the study area.

Methods

This study includes continuous groundwater observations (from 2016 to 2019) with high spatial and temporal resolution (20-min interval) from a detailed hill-slope transect, and an array of groundwater levels, water quality and spring flow observations within the Upper Lubigi catchment, a representative part of the city of Kampala (Fig. 1). Within the city and the greater Kampala area a wider range of observations are also drawn on—borehole logs, pumping test and abstraction data. High-resolution rainfall observations at 15-min intervals were also measured at a weather station at Naguru reservoir hill—0.35°N, 32.60°E; Macdonald et al. (2018)—whereas data on daily rainfall measured at Makerere University, about 4 km from Naguru hill (0.33°N, 32.57°E), were obtained from the Uganda National Meteorological Authority for the study period.

Geophysics: electrical resistivity tomography (ERT)

To investigate the overarching hydrogeological structure of the study area, electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) was carried out in six sections across the study area, each section about 250 m, giving a total length of 1,360 m (Fig. 1). The surveys were undertaken in a period between July and August 15 which represented a relatively dry season. The ERT lines consisted of five chains of active electrodes, each consisting of 20 electrodes with switch boxes at 5-m spacing. Different configurations (dipole-dipole, Schlumberger, Wenner etc.) were used in order to compare the results of different methods. Data were collected using a 4-point light 10 W earth resistivity meter (Lippmann Geophysical Instruments). Two-dimensional (2D) inversion techniques were used to evaluate the resistivity measurements (i.e. from apparent resistivities into real resistivities). The evaluation includes topography corrections and calibrations, for which the inversion program RES2DINVx64 was used. Before inversion, bad data points (i.e. very high, very low or negative apparent resistivities) were removed. These were likely due to poor electrode ground contact, dry soil, or other disturbing factors. The final outputs from the RES2DINVx64 software used in this study were real resistivity sections.

Drilling and installation of piezometers

Based on the outcomes of the ERT, a number of locations were selected for drilling and developing piezometers. In 14 locations, 23 boreholes (BH1-BH14, CR, CD) with depths ranging from 5 to 50 m were drilled using a small rotary air or mud drilling rig (PAT Drill 301) during the period from April to May 2016. At each site one, two or three boreholes with varying depths were drilled separately at 1–5 m from each other to minimise the likelihood of cross-connections. Every 2 m, drill cuttings were collected and the lithology described and recorded. In each borehole, 2-in. (5 cm) PVC pipes were installed with a 2-m slotted screen section at the bottom. The annular space was filled with (from bottom to top) 4–8 mm natural gravel packing, then a bentonite seal, followed by backfill material. Constructed boreholes were developed by both air lift and surging until the discharging water was clear. One piezometer (PL) was manually drilled with an auger up to 5 m depth in which a piezometer was installed with a 1-m screen at the bottom to obtain a deeper understanding of the interaction between springs and groundwater (see Fig. 1c). Finally, one borehole (BH12) was dry and was therefore abandoned.

Groundwater level observations

Eleven of the newly installed piezometers were equipped with pressure transducers (Minidiver, Schlumberger; Level Troll 100, In-Situ Inc.) to record pressure at a 20-min interval from August 2016 to June 2018. The barometric pressure, used to compensate data collected from the groundwater transducers, was measured inside a compound of a primary school in the study area using a barometric diver (Minidiver DI500; Schlumberger). In addition, for a number of piezometers, manual dip measurements of groundwater levels were recorded regularly from early 2016 to mid-2017 to verify the recorded groundwater levels (Table S3 in the ESM).

In order to determine recharge quantities from groundwater hydrographs, the water-table fluctuation method (Healy and Cook 2002) was used, focusing on the hydrographs nearer to the interfluve (ridge between two valleys) in order to minimise the impact of lateral flow on hydrograph response (i.e. BH1, BH5, BH10, and CR). A specific yield of 2–5% was assumed, as determined from pumping tests in schists and gneisses by Vouillamoz et al. (2014). This is also within range of values of specific yields estimated by several studies in the weathered regolith in Uganda: 0.1 by Taylor and Howard (1999, 2000), 0.001–0.01 by Howard and Karundu (1992) and 0.014 by Owor et al. (2018) for bedrock aquifers. The recharge was determined for 2017 and 2018.

Spring flow monitoring

A survey was undertaken to identify the locations and flows of all springs discharging from the Makerere Hill within the Upper Lubigi Catchment. This information was used to assess the hydrogeological controls on spring locations and the magnitude and variability of flow, which is representative of shallow groundwater. The spring locations were identified through the local knowledge of the authors and from consultation with local residents. Springs were classified as improved or unimproved, based on whether construction had been undertaken to protect the area of the spring and to focus the flow through discharge pipe(s). In total, 13 springs were identified of which four were unimproved. It was only possible to measure the flows from the improved springs. Monitoring of flows was carried out on a 2–3-day frequency over the period January to August 2019. Flow rates were measured manually by timing the filling of a container of known volume. Spring flows were compared to rainfall measured at a weather station at Naguru Reservoir within the catchment.

Aquifer properties

Slug tests were carried out in the newly installed piezometers to determine the transmissivity of the material surrounding the 2 m screen at the bottom of the piezometer. Per test, 1–2 bails were drawn using a steel bailer. Prior to drawing a bail, a pressure transducer was lowered into the piezometer to a few meters below the water level and set to measurement time intervals of 1 s. This allowed the recording of water-level change immediately after the bail was withdrawn. A number of tests were repeated in order to enhance the accuracy of transmissivity estimates. Data from all tests were analyzed using the software package MLU (Carlson and Randall 2012; Hemker 1999), which is based on a three-dimensional analytical solution for transient well flow in layered aquifer systems, whereby transmissivities and resistance values of the hydraulic system are determined via curve fitting. Resistance in this case is defined by the quotient of the saturated thickness and vertical hydraulic conductivity, usually of an aquitard. The saturated thickness was expressed in m, the hydraulic conductivity in meters per second (m/s), and the resistance in seconds (s). The saturated thickness was taken as the thickness of the screen.

BH1, BH2, and CR were fitted using an unconfined model configuration in MLU; all other tests were fitted assuming leaky aquifer conditions. In order not to overparameterise the fits, a vertical resistance of 10 days of the overlying aquitard was assumed. Furthermore, in all cases, the screen radius was fixed at 1 in. (2.54 cm; also the casing radius). Each fit was optimised for transmissivity, or permeability in case of unconfined conditions, and casing radius (rc).

In order to gain a better understanding of the variation in hydraulic properties across Kampala, data for constant rate pumping tests, collated by the Uganda Ministry of Water and Environment for licence applications for industrial abstractions, were analysed. The Logan method was used (Logan 1964) and compared with the Theis (1935) and Cooper and Jacob (1946) methods. Pumping test data associated with licence applications were assessed for a total of 18 sites in and round Kampala (Fig. 1).

Hydrochemistry and isotopes

Groundwater samples were collected from 23 piezometers, 8 springs and 3 rainfall samples from within the Upper Lubigi catchment. Samples were collected at irregular intervals during a period from November 2016 through February 2019. Piezometers were purged three well volumes prior to sampling to ensure a fresh, representative sample was collected. Field measurements for electrical conductivity (EC in μS/cm) standardised to 25 °C, temperature, and pH were carried out using Greisinger and Metler-Toledo meters. Alkalinity was determined onsite by titration using 0.2 M H2SO4. Nitrate was determined using the cadmium reduction method using the HACH DR 900 colorimeter. Other field measurements included phosphate, which was measured using the ascorbic acid method, sulphate using the SulfaVer method, and ammonium using the salicylate method using the HACH DR 900 colorimeter.

Total organic carbon was measured in the laboratory at IHE Delft on unfiltered samples after acidification and sparging inorganic carbon using sulphuric acid. Major anions and cations for 47 waters were analysed on filtered samples by ion chromatography and ICP-MS respectively in BGS and IHE Delft laboratories. Samples for cations were preserved using concentrated sulphuric acid up to a pH of less than 2. Analysed samples with ion balance errors in excess of ±15% were discarded. Unfiltered samples for stable isotopes and chlorofluorocarbon (CFC-11 and 12) dissolved gas samples were collected without atmospheric contact in sealed glass containers using the US Geological Survey method (USGS 2020). Stable isotope results are reported as a deviation from Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (vs. VSMOW) in per mil (‰) difference using delta (δ) notation. Unfiltered samples were collected for analysis of nitrogen (15N/14N) and oxygen (18O/16O) isotope ratios of nitrate. Nitrate was separated on anion resins and prepared as silver nitrate for analysis of 15N/14N and 18O/16O ratios by oxidative combustion and high-temperature pyrolysis, respectively, in Thermo Finnigan (Bremen, Germany) Flash 1112 and TC elemental analysers linked to a Delta+ XL mass spectrometer (Heaton et al. 2004). Isotope ratios were calculated as δ15N values vs. atmospheric N2 and δ18O values versus SMOW by comparison with IAEA standards N-1, N-2, and NO3. All CFC and stable isotope analysis was undertaken at BGS groundwater tracer and geochemistry laboratories in the UK. Global Network of Isotopes in Precipitation (GNIP) data from Entebbe airport (Uganda) were used to define the local meteoric water line (LMWL) for this study (GNIP 2019). Measurement precision was within ±0.1‰ for δ18O, ±1‰ for δ2H, and ± 5% for the CFCs, with detection limits of 0.01 pmol/L (CFC-12) and 0.05 pmol/L (CFC-11). An average annual air temperature of 25 °C was used, based on average groundwater temperatures, and an altitude of 1,000 m to temperature and pressure compensate the CFC data. Mean residence times for groundwaters are calculated based on a simple piston flow model (Małoszewski and Zuber 1982).

Results

Geological setting

As an example, an ERT cross-section with resistivities in the valley section near BH11 is presented in Fig. 2, whereby the location of the section is shown in Fig. 1. The top layer (0–5 mbgl) varied between a dry and sandy topsoil between distance X = 50 m and X = 150 m (200–500 Ohm-m), which was in use as a football field (no irrigation), and more clayey topsoil, which was a plot of land with subsistence crops between X = 150 m and X = 240 m (50–100 Ohm-m). Below, zones of lower resistivities (32–96 Ohm-m) were observed, which were interpreted as saturated weathered bedrock, and also with a piece of bedrock at X = 45 m with high resistivity (>2,000 Ohm-m). Furthermore, the boundary between weathered and parent rock appeared smooth and was around 30 m below ground surface at X = 80 m and around 10–15 m at X = 280 m. From the drilling returns, on the hills north and south of Bwaise, a reddish unconsolidated and unsorted material was found at the top, mainly composed of loamy silt and clay with occasional gravel sized fragments. This material was recognised and mapped as a ‘residual soil’ (see section ‘Introduction’) mainly composed of ferralitic laterite (Fig. 3).

Example electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) profile depicting the weathered overburden (low resistivities) and parent rock (high resistivities). Location of the section is given in Fig. 1 near BH11

Changes in lithology based on stratigraphic columns of all borehole drillings carried out in the study area. Colors describe the hydrogeological interpretation of the geology. Numbers indicate transmissivity (T) values determined from slug tests. The upper group of columns (excluding PL) is on/near hill tops. The lower group of columns plus PL is in/near valleys

As can be seen in Fig. 3, at some locations, e.g. in the vicinity of springs near B11, at the base of the ferralitic laterite, a layer of greyish-brown clay was observed. Below the residual soil (e.g. BH1), mixtures of yellowish-brown clayey silts were found, alternated with yellowish light-brown silts or white sandy clay. Occasionally, a rock fragment was hit, i.e. cobble or boulder of weathered parent material. Elsewhere, below the residual soil, the material was more composed of weathered rock here and there, alternated with sandy layers (e.g. BH2). In Fig. 3, these two types of deposits are named ‘sandy clay with rock fragments’ and ‘sandy weathered rock’. These two layers were interpreted as saprolite. Based on the borehole descriptions it was difficult to distinguish between upper saprolite (US) and lower saprolite (LS); see also the ‘Introduction’ section. Below the weathered rock, at depths varying from 15 to 45 m below the surface, the unweathered parent rock, or basement, was found. The depth of the basement at BH11 (≈25 m: Fig. 2) compared well with basement depths established from the ERT surveys (15–25 m; Fig. 2). South of Bwaise, on Makerere Hill, the basement rock had a granitoid red/pinkish appearance, while north of Bwaise, the same was true, except the basement rock contained more mica. In the valley (e.g. BH3, BH4, BH9), similar material was found, except that the top layer (<6 m) was composed, from top to bottom, of a brown loamy to gravelly fill or top soil, then fine grey or light sand and then stiff grey clay. This was interpreted to be palustrine deposits (clay) or alluvial (sands) sediment, likely deposited due to the development of a drainage system, which has nowadays become Lubigi swamp (indicated as wetlands in Fig. 1). Hydrogeologically, the clay layers within the residual soil and at its base and the clay layers in the alluvial fills were grouped as an aquitard, and below this aquitard, an aquifer was identified, mainly composed of weathered rock. The basement then forms the lower boundary of the groundwater system. It should be noted that, due to the relatively light drilling equipment used, because of the lack of space in the area, the depth to basement should be interpreted as depth to the uppermost presence of parent rock. When this type of hard rock was hit, drilling could not continue. Deeper weathering, however, including the presence of a saprock transitioning with depth into bedrock, could have occurred. However, since the drilling depth to basement and ERT depth to basement coincided well, the study was confident that basement as indicated in Figs. 3 and 4 is correct. Figure 4 summarises the hydrogeological characteristics of the regolith.

Hydrogeology and equipotential lines in a borehole cross-section. Cross section is indicated in Fig. 1. Hatched areas: presence suspected/extrapolated

Groundwater level fluctuations and spring flow

At the top of the hill at BH1, the groundwater level was 1200 masl (Fig. 4), 35–40 m below ground level (mbgl) and only a few metres above the top of the bedrock. The cross-section in Fig. 4 shows a transect approximately perpendicular to the topographic gradient from Makerere Hill to Bwaise and then up towards Nabweru (Fig. 1) The equipotential contours in Fig. 4 show a groundwater gradient in the direction of Bwaise valley from both Makerere Hill and Nabweru. The Nsooba drain is a piezometric low point on the transect.

Figure 5 shows two panels of groundwater level time series for selected sites while Table S3 in the ESM shows the average water levels of all the sites. There were gaps in the recorded time series either because the diver memory was full or the logging was interrupted with manual measurements. However, these gaps did not affect the analysis of the results. Piezometers at locations B11 and B3, both immediately adjacent to the Nsooba drain, showed the presence of a vertically upward-directed groundwater gradient when the shallower and deeper piezometric levels were compared. On either side of the valley (e.g. B11 and BH4), close to the hills, where topographic gradients change, groundwater was artesian (Fig. 4).

During the period of monitoring, the fluctuations in the groundwater levels in the piezometers were small, in all cases less than 1 m (Fig. 5). The groundwater level hydrographs fall broadly into four categories—those that rise and fall rapidly with a relatively small amplitude (BH7, BH8, BH9, BH11); those that have a smooth seasonal cycle (BH10, CR); BH5 that has a response that has characteristics of both of the first two categories; and BH1, in which no significant groundwater level rise occurred from January 2017. In most cases except in BH1, there was a delayed response to peak monthly rainfall; for instance, for BH10, only three periods of groundwater level rise were observed, which came 1–2 months after periods of heavy rainfall. Piezometers at BH1, BH10, and CR are situated near the hill tops (or interfluve) where there are unconfined conditions and substantial unsaturated zone thicknesses (BH1 45 m, BH10 20 m and CR 22 m, respectively; Figs. 1 and 4). The distinctive response in BH1 may be a combination of the greater thickness of the unsaturated zone at BH1 and the nature of the weathered material that occurs at the higher elevations. In the case of the remaining groundwater hydrographs, the more rapid and spikey responses to recharge were due to either (semi)confining conditions or smaller thickness of the unsaturated zone. Of these, BH11 (11 m) and BH8 (18 m) were artesian and located in the valley bottom (Figs. 1 and 4), whereas BH5 is situated in between the hill top and valley bottom and has a head that is influenced by both unconfined and semiconfined conditions.

The 13 springs identified through the spring survey (Fig. 1) were all located at the foot of Makerere Hill at a similar elevation. A selection of measured spring flows is presented in Fig. 6, along with daily rainfall from Naguru Reservoir site. Flow rates in all but one of the 13 springs were less than 1 L/s (0.001 m3/s) throughout the monitoring period (Table S4 in the ESM). The exception was SP40, which ranged between 4.2 and 5.5 L/s (or 0.0042 and 0.0055 m3/s), which was likely associated with a local fracture zone in the bedrock. All springs showed a rapid response in flow to rainfall events during the period of monitoring; however, the responses were not consistent across all events, and some springs were more responsive than others. Rainfall events that were relatively intense and spanned a number of days such as those in mid-February and mid-May 2019 (Fig. 6), did result in a rapid response in flow rate across all springs. The absolute changes in the magnitude of the rate of spring SP40 in response to rainfall, was by far the greatest across all those monitored; noticeable but small recessions occurred across all springs during relatively dry periods.

Groundwater recharge

From the groundwater hydrographs (Fig. 5), it is clear that the number of recharge events per year (2017 or 2018) was limited to three at most. The duration of such ‘events’, however, was long and could easily take between 50 and 100 days, indicating continued low recharge rates for long periods during and after periods of sustained rainfall.

Groundwater recharge was estimated for 2017 and 2018 (see Table S2 in the ESM), assuming a specific yield of 2–5%, as determined from pumping tests in schists and gneisses by Vouillamoz et al. (2014). For BH1 separate recharge events were not evident; instead, from the observed overall water-table fluctuation of 80 cm, being the difference between minimum and maximum recorded levels, in 2 years, this study determined a recharge of 800 × (0.02–0.05) = 16–40 mm in 2 years or 8–20 mm/year. For BH5, BH10, and CR, the recharge from precipitation in the area on top of the hills, where groundwater conditions were unconfined, ranged from 3 to 24 mm in 2017 and from 10 to 50 mm in 2018.

Aquifer properties

For each slug test, 100 s of data points were collected (see a typical example in Fig. S1 in the ESM), which reduced uncertainties in fitted parameter values, evidenced by the low standard deviations (SD) and errors in the sum of the squared differences between each observation and calculated value (SD and SSE values, respectively, in Table 1). From Table 1 and Fig. 3, it is clear that the transmissivity of the aquifer is rather low: on average 1.1 × 10−6–1.1 × 10−5 m2/s up to a maximum of 4.9 × 10−3 m2/s at BH3 (24 m). In terms of spatial distribution patterns, the study observed that transmissivities of the western-most locations CD, BH13 and BH14 near or in the valley floor were appreciably higher (1.4 × 10−5–1.2 × 10−4 m2/s) than of the other locations (see Table 1).

Pumping tests analysed from industrial licence applications broadly corroborate the results of the slug test analysis. It is however important to highlight that slug tests can have errors when compared to pumping tests because they are only able to sample a small region around the well which may not be representative of the actual transmissivity (T) of the aquifer (Butler and Healey 1998; Rovey and Cherkauer 1995). From the 16 pumping tests analysed using the Logan (1964) method, a median transmissivity of 5.6 × 10−5 m2/s or (4.81 m2/day) was estimated. The Logan (1964) method agreed well with the Theis (1935) and Cooper and Jacob (1946) for two sites where detailed data exist (range of 1.2 × 10−5 – 2.3 × 10−5 m2/s or 0.1–2 m2/day). There is notable spatial variability in the transmissivity estimates, with differences of up to 10 m2/day (or 1.2 × 10−4 m2/s) at the same site (Fig. 1).

Hydrochemistry and isotopes

Hydrochemical characteristics

The EC of precipitation water (rainwater; Table S1 in the ESM) was around 40 μS/cm, had near neutral pH values (range of 6.2–7.4) and with chloride ranging from 4.4 to 11.5 mg/L. In both samples, some nitrogen was present as ammonium (2–5 mg/L) and nitrate (<8.41 mg/L NO3; Table S1 in the ESM).

Shallow groundwater from springs had EC ranging from 226 to 810 μS/cm (average of 471 μS/cm), had low pH values (4.7–5.0; average 4.9), and high nitrate concentrations, from 61 to 190 mg/L.

Groundwater from the piezometers was moderately acidic to neutral with pH values ranging from 5.0 to 7.3, but mainly between 6 and 6.5, and with relatively low nitrate (and ammonium) concentrations. The EC of these piezometers ranged from 88 to 502 μS/cm with an average value of 221 μS/cm; deeper piezometers had lower EC and nitrate compared to shallow piezometers (Table S1 in the ESM). In a number of the samples (n = 36; about 78%), nitrate was present, although typically in low concentrations (<20 mg/L). For BH8 and BH11 higher nitrate concentrations (9.74–14.6 mg/L) were observed for the deeper piezometer than for the shallower piezometer (<1 mg/L) indicating that nitrogen removal in the shallow aquifer was likely taking place.

In all, 30% of piezometer groundwater sites analysed had manganese (Mn) concentrations exceeding 100 μg/L and 27% exceeding the WHO health based guideline limit of 400 μg/L (WHO 2017); 85% of spring samples were found with concentrations exceeding 400 μg/L. Fluoride was found in high concentrations, 7.6 mg/L, at one site (9D), otherwise all other groundwater samples were below the WHO health-based guideline limit of 1.5 mg/L. Arsenic and lead were below the WHO guideline value of 10 μg/L for all groundwater samples including springs.

Figure 7b shows a cross-plot of nitrate vs. EC results for 35 piezometers, 2 hand pumps and 8 spring samples. There is a significant positive correlation between the two parameters (Spearman’s correlation coefficient, ρ = 0.57, and a statistical significance, p < 0.001), although the spread of results for piezometer sites is considerable, with higher EC and nitrate samples for springs and hand pumps compared to piezometers. Three shallow piezometer sites (BH7S, BH5S and BH3S) do not conform to the hydrochemistry of the other piezometers and show evidence of nitrate contamination (BH7S and BH5S) and high EC at all sites suggesting that they are supplied by the same aquifer as for the springs.

Hydrochemical results. a cross-plot of water δ18O vs. δ2H for rainfall, groundwater and grey water, b cross-plot of NO3 vs EC for different groundwaters, c cross-plot of CFC-12 vs CFC-11 for groundwater samples, d cross-plot of NO3–δ15N vs NO3–δ18O in groundwater and grey water. Letters S and D after the sample label indicate shallow and deep piezometers respectively

Water stable isotopes

Water stable isotope results are summarised in Fig. 7a. The water stable isotopic signatures of grey waters (domestic waste water) were significantly enriched (δ18O = 4‰, δ2H = 30‰) compared to other waters sampled in the area. Samples from drains and springs plot on or below the LMWL, and are typically slightly enriched compared to piezometer samples which plot on the LMWL and also show greater variability compared to the piezometers (Fig. 7a); this is particularly evident for spring L1 and hand pump L2 which are highly enriched compared to the other spring waters.

Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) age dating of spring water and shallow groundwater

Figure 7c shows a cross-plot for CFC-12 vs CFC-11 for deep piezometers and one spring sample orientated along the groundwater flow transect (see Fig. 1); the subplot shows all results and the large plot shows the subset of results for which anthropogenic CFC contamination is not apparent. There is a highly significant positive correlation (ρ = 0.98, p < 0.001) between the two tracers and all samples had detections for both tracers. Considerable CFC contamination was noted at the spring site L1, BH7D and BH2D, likely from a localised source; however, results from five piezometers reveal no evidence of CFC contamination. Well BH7D likely taps from the shallow aquifer. The piezometer samples were aerobic and had low Fe concentrations so microbiological degradation is an unlikely explanation for the low CFC results found in these samples (Hinsby et al. 2007; Sebol et al. 2007). The most likely explanation is that these low CFC groundwaters have mean residence times that are considerably older than the CFC contaminated sites, and are more isolated hydraulically (i.e. not recharged directly) from the shallower groundwater system, which is represented by the spring L1 which shows an intermediate level of CFC contamination. Using a simple piston flow model (Małoszewski and Zuber 1982), groundwater mean residence times (MRT) for the six groundwaters were found to be between 40 and 65 years; the CFC-11 piston flow MRT for the spring (L1) was 30 years; however, this likely represents a mixture of contributions from both shallow and deeper groundwater systems. Hence, if a binary mixing model is assumed, using end members of modern and tracer ‘dead’ older groundwater, the six groundwater samples gave modern proportions of 3–100%. The spring site L1 had 100% modern groundwater and the deep piezometer 8D had 3% modern groundwater; sites 10D and 5D had 42 and 15%, respectively, and sites CD-D and BH3-D both had 6% modern groundwater.

Isotopes of nitrate (δ15N and δ18O)

The results for isotopes of nitrate are shown in Fig. 7d, which show isotopically distinct signatures for grey waters compared to drainage channel water and groundwaters. All nitrogen isotope spring/drainage-channel samples and some groundwater samples from piezometers plot along a line; the enriched NO3–δ15N and δ18O values possibly indicate that denitrification may be important in selected springs and piezometers as nitrate is processed in the soil and shallow subsurface (Matiatos et al. 2021). The nitrate isotopes (δ15N and δ18O) of the bottom left-hand end-members in Fig. 7d (BH11-D and BH3-S), which are located furthest downgradient of the transect (see Fig. 4), were more depleted than for other members.

Discussion

Hydrogeological characterisation and formation of springs

Results from the drilling and ERT analyses showed a geology of weathered regolith 20–50-m thick overlying a basement rock. A four-layer geological model as noted from previous studies (e.g. Wright 1992; Chardon et al. 2018; Bianchi et al. 2020) is evident (Fig. 4): a residual soil mainly composed of ferralitic laterite on hill tops and slopes, a saprolite layer comprising sandy clay with rock fragments, the saprock largely consisting of weathered bedrock (original rock fabric that has been altered and crumbles by hand to individual grains) and, finally, the fresh bedrock. Although laterites are primarily formed on hill tops, it is possible to have laterite on the hill slopes and the low-lying side of hills which are mainly composed of debris derived from breakup and downslope movement of hill laterites/ferricretes, as noted by Babar (2007). In the valleys, there exist stiff clays and fine sands which give rise to a shallow alluvial fill aquifer system capped by a clayey formation. These were formed as a result of continuous erosion and deposition that likely occurred over time following river drainage patterns developed since the Miocene era (see Kayima et al. 2018; Nyenje et al. 2014a). This geological model influences a diverse pattern of shallow groundwater systems consisting of unconfined conditions in the higher parts of the area, the hills, and (semi) confined conditions in the valleys. Consequently, piezometric levels in the unconfined aquifer (e.g. BH1, BH10 and CR) had delayed responses, whereas those in the confined aquifer (e.g. BH11 and BH8) had quick responses (see Fig. 5).

Groundwater flow largely follows the topographical gradient, whereby recharge occurs in the hills and discharge in the valleys as springs and in Nsooba channel (see Figs. 1 and 4). Springs appear to be formed when the shallow groundwater flowing though the weathered regolith is intercepted in the valley by an underlying stiff clayey layer forcing groundwater emergence. A comparison of the geological logs and piezometric levels of BH2 and BH11 (see Figs. 3 and 4) shows that in the area between these two sites, there exists a weathered regolith (the saprolite and below) containing significant amounts of water that is overlain by laterite. It can also be seen from piezometer PL, which is located near the springs (Fig. 4), that the water table here follows a smooth gradient from BH1, BH2 and the spring, which is the discharge point. However, the flashy nature of the springs, as shown in Fig. 6, suggests that spring flows may be a combination of base flow from the regolith aquifer and interflow in the shallow post-erosional ferricrete layer.

From a combination of the stable isotope enrichment, higher nitrate, and EC and CFC tracers, it can be inferred that spring discharge represents a much shallower groundwater flow system compared to the deeper groundwater (represented by piezometer samples). The hydrochemically stratified groundwater system suggests that deep groundwater in the saprock and fractured bedrock is largely hydraulically isolated from the shallow system in the saprolite and shallow saprock and is recharged by diffuse meteoric sources, some of which may predate the era of dense populations seen today. The water stable isotopes of spring and piezometer samples plotted on or below the LMWL (Fig. 7a) demonstrate diffuse meteoric recharge. The shallow aquifer feeding the springs is also likely to have a recharge contribution of grey water (domestic wastewater) from municipal supplies contaminated by local wastewater inputs given that the water stable isotopes of some springs plotted below the LMWL and were slightly enriched.

Groundwater recharge was estimated to range between 3 and 50 mm/year over the period 2017–2018. Recently, MacDonald et al. (2021) reported a long-term average groundwater recharge rate for Uganda of approximately 1 m/decade (≈100 mm/year), while Banks et al. (2021) reported average estimated recharge rates using different techniques (CFCs, chloride mass balance, and water table fluctuation method) of 27–110 mm/year for sites in Uganda. Others (Mileham et al. 2008; Nyenje and Batelaan 2009; Taylor and Howard 1996) found recharge rates in the order of 100–250 mm/year for specific study sites in Uganda. These estimates were lower than the ranges determined by these authors, possibly due to the large ‘paved’ or ‘roofed’ surface area of the catchment. The study period was also limited to 2017–2018, which may not be necessarily representative of the average rainfall in the area. Springs in the area showed a rapid response in flow to rainfall events during the period of monitoring; however, responses were not consistent across all events, and some springs were more responsive than others.

The transmissivities of sandy clay soils which characterise the saprolite where a large part of the aquifer is located were low and in the range of 1 × 10−6–1 × 10−5 m2/s or 0.1–1.0 m2/day with only occasionally high yielding sites (up to 4.9 × 10−3 m2/s or 423 m2/day). High yielding sites in crystalline bedrock aquifers are those with transmissivities of 10–1,000 m2/day (Maurice et al. 2019).

Conceptual model of the groundwater flow system

Figure 8 shows a simplified schematic of the entire groundwater flow system in the upper Lubigi catchment following the preceding discussion. Groundwater quality of the deeper part of the groundwater system (shown as type 1; Fig. 8) can be characterised as aerobic with low values of EC (<300 μS/cm) and NO3 (<23 mg/L) and with pH in the range of 5–6. The low NO3 concentrations originate from diffuse infiltration of wastewater from onsite sanitation in the recharge areas, which has potentially undergone denitrification. This is evident from Fig. 7d where δ15N–NO3 values in wells upgradient of the transect were significantly enriched (δ15N > 20‰; e.g. BH2 and BH1) compared to wells furthest downgradient of the transect (δ15N < 15‰; e.g. BH11-D). Nitrate and EC of piezometer samples did not show any significant correlation (Fig. 7b); demonstrating that denitrification likely took place. Mean residence times estimated using CFC tracers were in the range 30–60 years.

Groundwater in the ferralitic laterite (type 2; Fig. 8), which feeds the springs and is also represented by wells BH5 and BH7, is also aerobic and characterised by lower pH values (<5), high NO3 values (>60 mg/L), and younger residence time (<30 years). The low pH values are attributed to the limited buffering capacity of the ferricrete. The groundwater spring system appears to occur at the interface of the lateritic slope debris and the saprorite and shows evidence of recharge from a combination of precipitation recharge, wastewater infiltration and contributions from the deeper groundwater system based on the results of isotopes, hydrochemistry and CFC tracer analyses. It is hypothesised that the high nitrate concentrations are due to nitrification of wastewater N sources during infiltration. Isotopes of nitrate (δ15N, δ18O) are often used to identify sources of NO3 in groundwater (Kendall and McDonnell 1998) and have recently been used in this region (Nyilitya et al. 2021). The abundance of δ15N, for example, is usually greater in human sewage (+4 to +6‰) than other sources such as precipitation (−7 to 1‰), soil organic N (≈0%), and inorganic fertilizers (−3 to +3‰; Jones et al. 2018). δ15N values of the groundwater samples were enriched and ranged from +5.9 to 26‰ (mean ±SD = 15 ± 6.82‰) which suggests that human sewage from onsite sanitation practices was indeed the likely source of NO3 in the shallow groundwater. The ratio of NO3/Cl (0.9, see the ESM) was also high which further confirms that much of the NO3 was from human sewage and most likely from pit latrines and septic tanks (including grey water). The grey water samples had a distinct isotopic composition with high δ18O–NO3 (>25‰; Fig. 7d) and significantly enriched with water stable isotopes (δ18O = 4‰, δ2H = 30‰; Fig. 7a) compared to springs and other samples. These two grey water samples were interpreted as the retained signature of Lake Victoria water, which is the source of piped drinking water in much of Kampala and is provided for in the area via standpipes, in-house taps, and yard taps. They look pristine and are typical of NO3 in precipitation. Modification due to mixing with other sources cannot be ruled out but is not likely to change the isotopic composition significantly.

In the valley, shallow alluvial groundwater classified as type 3 (Fig. 8), which forms the upper 2–3 m, is of an entirely different composition, as is clear from the work of Nyenje et al. (2014a). Here, due to direct infiltration of wastewater or due to the presence of organic materials in the alluvial fill material, or both, groundwater is anaerobic with high concentrations of mobile Fe II and Mn II (e.g. well BH3 (3 m), BH8 (3 m), BH11 (3 m) and CD (3 m)). Nitrate is almost absent and instead ammonium concentrations can be very high. It is also possible that nitrogen was removed from the shallow aquifer due to denitrification, possibly facilitated by more reducing conditions as noted in previous studies (e.g. Nyenje et al. 2014a; Kulabako et al. 2007).

Implications for future development of urban groundwater supplies

The urban basement aquifer system previously described has low groundwater yields; therefore, only small-scale abstractions for private or self-supply by communities are possible. However, direct consumption without treatment should be discouraged because of the low quality of this groundwater. It is realised in this study that this may not be possible, because many urban low-income dwellers usually do not have other low-cost alternatives other than using groundwater from springs, as these flow freely due to gravity (Kulabako et al. 2007; Nyenje et al. 2014b). These springs and shallow groundwater flow systems are also partly recharged by wastewater infiltration. Consequently, water quality impacts from wastewater infiltration from pit latrines, septic tanks and wastewater discharge will remain a big concern for urban dwellers who use and rely on shallow groundwater sources.

There is possibility to access groundwater in areas with artesian conditions in the deeper groundwater system in the valley bottom. This deeper regional groundwater has better chemical quality than groundwater from springs and thus local authorities could explore this resource using boreholes tapping the saprock for small-scale local consumption as a low-cost water supply alternative to springs. The microbial water quality and other water quality aspects (Mn and nitrate) also need to be considered and suitable treatment used to safeguard public health from contaminated drinking-water sources. However, it is important to note that transmissivities are low and therefore large-scale pumping will not be feasible. More intensive abstraction from this semiconfined aquifer could also change the current groundwater flow regime and in time draw in shallower, more contaminated, groundwater. Further development of the deeper groundwater systems would need adequate monitoring of groundwater levels and quality.

Future changes in climate in this region are highly uncertain (Bornemann et al. 2019). More intensive precipitation events could potentially enhance groundwater recharge and spring flow in this relatively humid region (Jasechko and Taylor 2015; Owor et al. 2009). Further urbanisation and greater surface sealing may change infiltration processes and could focus more flow via surface and shallow subsurface routes, resulting in more flooding and higher peak spring flows.

Conclusions

The aim of this article was to develop a critical understanding of the hydrogeology and flow systems in a crystalline basement/regolith aquifer in an urban tropical area. The study has provided new hydrological insights for the urban basement aquifers.

Findings showed that the hydrogeology of basement aquifers in Kampala can be classified into a four-layer geology model consisting of (1) a ferricrete or laterite layer at the top, which is a hardened and porous layer, (2) the saprolite consisting of mainly sandy clays with rock fragments and forming a large part of the weathered regolith, (3) the saprock (weathered rocks) and (4) the hardened basement rock.

This hydrogeological setting restricts groundwater resources in the study area to a weathered basement layer with thicknesses in the range of 20–50 m. This weathered crystalline basement is a low groundwater storage system with low transmissivities (<1 × 10−5 m2/s), mostly unconfined and highly vulnerable to contamination due to recharge from wastewater infiltration from onsite sanitation systems such as pit latrines.

The geomorphology of the study area comprises low hills and valleys formed as a result of long-term fluvial processes giving rise to confined conditions in the valleys due to a clay capping system formed as a result of weathering and depositions from eroded hillslope material. The confined areas in the valleys give rise to artesian conditions and groundwater with lower nitrate concentrations, compared to the shallow system, as it is less impacted by wastewater sources of pollution.

Groundwater recharge is in the range of 3–50 mm/year and occurs in the hills, with discharges in the valleys either as springs, exfiltration to streams or contribution to the deep groundwater system.

Recharge from precipitation to the deeper groundwater is associated with prolonged periods of relatively heavy rainfall, while recharge to the shallow system and the springs appears episodic and linked to interflow in the shallow ferralitic laterite zone caused by changes in precipitation as well as a substantial base flow from the deeper regolith aquifer system.

The springs appear to be formed when groundwater flowing through the weathered regolith is intercepted by underlying stiff clay deposits in the valley bottoms. These springs, which are the main source of low-cost drinking water for the urban poor in this study area, mainly discharge more modern groundwater (residence time < 30 years) flowing through the ferralitic laterite located above a more regional deep groundwater system in the sandy clay formation (saprolite). This shallow groundwater is however a mixture of both precipitation recharge and wastewater infiltrating from onsite sanitation systems and is therefore of poor water quality with low pH values and high NO3 concentrations. Based on the analysis of nitrogen and oxygen isotopic compositions of nitrate, infiltration of wastewater from onsite sanitation facilities is shown as the main source of nitrogen in groundwater.

The system that has been studied in Lubigi is repeated across Kampala, and beyond, as a series of hills capped by ferricrete and separated by low-lying swampy land cover (Fig. S2 in the ESM). As such, the hydrogeology results of this study have wider application in other parts of Kampala and other comparable fluvially dissected, lateritic, regolith-covered basement terrains. Groundwater yields in this aquifer systems appear to be low, which restricts groundwater abstractions to small-scale private consumption facilities (e.g. water bottling industries) or small community water supplies.

References

Acworth RI (1981) The evaluation of groundwater resources in the crystalline basement of northern Nigeria. PhD Thesis, University of Birmingham, UK. https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/id/eprint/3576/. Accessed 22 Feb 2022

Alle IC, Descloitres M, Vouillamoz JM, Yalo N, Lawson FMA, Adihou AC (2018) Why 1D electrical resistivity techniques can result in inaccurate siting of boreholes in hard rock aquifers and why electrical resistivity tomography must be preferred: the example of Benin, West Africa. J Afr Earth Sci 139:341–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAFREARSCI.2017.12.007

Babar M (2007) Environmental changes and natural disasters. In: Sawant PT, Sathe NJ (eds) Influence of lineaments on landslide prone area around Mahad Raigad District Maharashtra. New India Publishing Agency, New Delhi, pp 197–213

Banks EW, Cook PG, Owor M, Okullo J, Kebede S, Nedaw D, Mleta P, Fallas H, Gooddy D, MacAllister DJ, Mkandawire T (2021) Environmental tracers to evaluate groundwater residence times and water quality risk in shallow unconfined aquifers in sub Saharan Africa. J Hydrol 598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125753

Barrett MH, Hiscock KM, Pedley S, Lerner DN, Tellam JH, French MJ (1999) Marker species for identifying urban groundwater recharge sources: a review and case study in Nottingham, UK. Water Res 33:3083–3097

Belle P, Lachassagne P, Mathieu F, Barbet C, Brisset N, Gourry JC (2019) Characterization and location of the laminated layer within hard rock weathering profiles from electrical resistivity tomography: implications for water well siting. Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ 479:187–205

Bianchi M, MacDonald AM, Macdonald DMJ, Asare EB (2020) Investigating the productivity and sustainability of weathered basement aquifers in tropical Africa using numerical simulation and global sensitivity analysis. Water Resour Res 56(9). https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR027746

Bonsor HC, MacDonald AM, Davies J (2014) Evidence for extreme variations in the permeability of laterite from a detailed analysis of well behaviour in Nigeria. Hydrol Process 28:3563–3573. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.9871

Bornemann FJ, Rowell DP, Evans B, Lapworth DJ, Lwiza K, Macdonald DM, Marsham JH, Tesfaye K, Ascott MJ, Way C (2019) Future changes and uncertainty in decision-relevant measures of East African climate. Clim Chang 156:365–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02499-2

Butler JJ, Healey JM (1998) Relationship between pumping-test and slug-test parameters: scale effect or artifact?. Groundwater 36(2):305–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6584.1998.tb01096.x

Carlson F, Randall J (2012) MLU: a windows application for the analysis of aquifer tests and the design of well fields in layered systems. Ground Water 50:504–510

Carter RC, Parker A (2009) Climate change, population trends and groundwater in Africa. Hydrol Sci J 54:676–689. https://doi.org/10.1623/hysj.54.4.676

Chardon D, Grimaud JL, Beauvais A, Bamba O (2018) West African lateritic pediments: landform-regolith evolution processes and mineral exploration pitfalls. Earth-Sci Rev 179:124–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2018.02.009

Chilton PJ, Foster SSD (1995) Hydrogeological characterisation and water-supply potential of basement aquifers in tropical Africa. Hydrogeol J 3:36–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s100400050061

Cooper HH, Jacob CE (1946) A generalized graphical method for evaluating formation constants and summarizing well-field history. EOS Trans Am Geophys Union 27:526–534. https://doi.org/10.1029/TR027i004p00526

Courtois N, Lachassagne P, Wyns R, Blanchin R, Bougaïré FD, Somé S, Tapsoba A (2010) Large-scale mapping of hard-rock aquifer properties applied to Burkina Faso. Groundwater 48:269–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1745-6584.2009.00620.X

Cuthbert MO, Taylor RG, Favreau G, , Todd MC, Shamsudduha M, Villholth KG, MacDonald AM, Scanlon BR, Kotchoni DO, Vouillamoz JM, Lawson F (2019) Observed controls on resilience of groundwater to climate variability in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature 572:230–234. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1441-7

Dewandel B, Lachassagne P, Wyns R, Maréchal JC, Krishnamurthy NS (2006) A generalized 3-D geological and hydrogeological conceptual model of granite aquifers controlled by single or multiphase weathering. J Hydrol 330:260–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2006.03.026

Flynn R, Taylor R, Kulabako R, Miret-Gaspa M (2012) Haematite in lateritic soils aids groundwater disinfection. Water Air Soil Pollut 223:2405–2416

Foster S, Sage R (2017) Groundwater science in water-utility operations: global reflections on current status and future needs. Hydrogeol J 25:1233–1236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-017-1602-4

Fuhrimann S, Winkler MS, Kabatereine NB, Tukahebwa EM, Halage AA, Rutebemberwa E, Medlicott K, Schindler C, Utzinger J, Cissé G (2016) Risk of intestinal parasitic infections in people with different exposures to wastewater and fecal sludge in Kampala, Uganda: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004469

Gaye CB, Tindimugaya C (2019) Review: Challenges and opportunities for sustainable groundwater management in Africa. Hydrogeol J 27:1099–1110

GNIP (2019) Global network of isotopes in precipitation (GNIP) 2019. Data Entebbe Airpt. https://www.iaea.org/services/networks/gnip. Accessed March 2022

Grönwall J (2016) Self-supply and accountability: to govern or not to govern groundwater for the (peri-) urban poor in Accra, Ghana. J Environ Earth Sci 75:1163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-016-5978-6

Guma BE, Owor M, Muwanga A (2019) Hydrogeological characteristics of the Albertine graben, Uganda: evidence from surface geophysics and hydraulic testing. J Afr Earth Sci 150:224–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAFREARSCI.2018.11.008

Healy RW, Cook PG (2002) Using groundwater levels to estimate recharge. Hydrogeol J 10:91–109

Heaton THE, Wynn P, Tye AM (2004) Low 15N/14N ratios for nitrate in snow in the High Arctic (79°N). Atmos Environ 38(33):5611–5621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2004.06.028

Hemker CJ (1999) Transient well flow in layered aquifer systems: the uniform well-face drawdown solution. J Hydrol 225:19–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1694(99)00093-1

Hinsby K, Højberg AL, Engesgaard P, Jensen KH, Larsen F, Plummer LN, Busenberg E (2007) Transport and degradation of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in the pyritic Rabis Creek aquifer, Denmark. Water Resour Res 43. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006WR005854

Howard KWF, Karundu J (1992) Constraints on the exploitation of basement aquifers in East Africa — water balance implications and the role of the regolith. J Hydrol 139(1–4):183–196 https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1694(92)90201-6

Howard G, Pedley S, Barrett M, Nalubega M, Johal K (2003) Risk factors contributing to microbiological contamination of shallow groundwater in Kampala, Uganda. Water Res 37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1354(03)00235-5

Jasechko S, Taylor RG (2015) Intensive rainfall recharges tropical groundwaters. Environ Res Lett 10. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/12/124015

Jones MJ (1985) The weathered zone aquifers of the basement complex areas of Africa. Q J Eng Geol. https://doi.org/10.1144/gsl.qjeg.1985.018.01.06

Jones BL, Cullen-Unsworth LC, Unsworth RKF (2018) Tracking nitrogen source using δ15 N reveals human and agricultural drivers of seagrass degradation across the British Isles. Front Plant Sci 9:133. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPLS.2018.00133/BIBTEX

Kansiime F, Kateyo E, Oryem-Origa H, Mucunguzi P (2007) Nutrient status and retention in pristine and disturbed wetlands in Uganda: management implications. Wetl Ecol Manag 15(6):453–467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-007-9054-6

Katukiza AY, Ronteltap M, Oleja A, Niwagaba CB, Kansiime F (2010) Lens PN (2010) selection of sustainable sanitation technologies for urban slums: a case of Bwaise III in Kampala, Uganda. Sci Total Environ 409(1):52–62

Katukiza AY, Ronteltap M, Van Der Steen P, Foppen JW, Lens PN (2014) Quantification of microbial risks to human health caused by waterborne viruses and bacteria in an urban slum. J Appl Microbiol 116:447–463

Katukiza AY, Ronteltap M, Niwagaba CB, Kansiime F, Lens PNL (2015) Grey water characterisation and pollutant loads in an urban slum. Int J Environ Sci Technol 12(2):423–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-013-0451-5

Kayima JK, Mayo AW, Nobert J (2018) Ecological characteristics and morphological features of the Lubigi wetland in Uganda. Environ Ecol Res 6:218–228. https://doi.org/10.13189/eer.2018.060402

Kendall C, McDonnell JJ (eds) (1998) Isotope tracers in catchment hydrology. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 839 pp

Komakech HC, de Bont C (2018) Differentiated access: challenges of equitable and sustainable groundwater exploitation in Tanzania. Water Altern 11(3):623–637

Kulabako NR, Nalubega M, Thunvik R (2007) Study of the impact of land use and hydrogeological settings on the shallow groundwater quality in a peri-urban area of Kampala, Uganda. Sci Total Environ 381(1–3):180–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.03.035

Kulabako NR, Nalubega M, Thunvik R (2008) Phosphorus transport in shallow groundwater in peri-urban Kampala, Uganda: results from field and laboratory measurements. Environ Geol 53(7):1535–1551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-007-0764-0

Kulabako RN, Nalubega M, Wozei E, Thunvik R (2010) Environmental health practices, constraints and possible interventions in peri-urban settlements in developing countries: a review of Kampala, Uganda. Int J Environ Health Res 20(4):231–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603120903545745

Kyambadde J, Kansiime F, Gumaelius L, Dalhammar G (2004) Hydraulic loading, stability and water quality of Nakivubo wetland, Uganda. Afr J Aquat Sci 29(2):213–220. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085910409503812

Lachassagne P (2008) Overview of the hydrogeology of hard rock aquifers: applications for their survey, management, modelling and protection. In: Ahmed S, Jayakumar R, Salih A (eds.) Groundwater dynamics in hard rock aquifers. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 40–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6540-8_3

Lachassagne P, Wyns R, Dewandel B (2011) The fracture permeability of hard rock aquifers is due neither to tectonics, nor to unloading, but to weathering processes. Terra Nov 23:145–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3121.2011.00998.x

Lachassagne P, Dewandel B, Wyns R (2014) The conceptual model of weathered hard rock aquifers and its practical applications. In: Sharp, J.M., Jr. (ed.) Fractured rock hydrogeology. International Association of Hydrogeologists Selected Papers, No. 20. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp 13–46

Lachassagne P, Dewandel B, Wyns R (2021) Review: Hydrogeology of weathered crystalline/hard-rock aquifers—guidelines for the operational survey and management of their groundwater resources. Hydrogeol J 29:2561–2594. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10040-021-02339-7/FIGURES/17

Lapworth DJ, Nkhuwa DCW, Okotto-Okotto J, Okotto-Okotto J, Pedley S, Stuart ME, Tijani MN, Wright JJ (2017) Urban groundwater quality in sub-Saharan Africa: current status and implications for water security and public health. Hydrogeol J 25:1093–1116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-016-1516-6

Logan J (1964) Estimating transmissibility from routine production tests of water wells. Ground Water 2:35–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6584.1964.tb01744.x

Lutterodt G, Foppen JWA, Uhlenbrook S (2012) Transport of Escherichia coli strains isolated from natural spring water. J Contam Hydrol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2012.08.011

Lutterodt G, Foppen JWA, Uhlenbrook S (2014) Escherichia coli strains harvested from springs in Kampala, Uganda: cell characterization and transport in saturated porous media. Hydrol Process 28:1973–1988

Lutterodt G, Van de Vossenberg J, Hoiting Y, Kamara AK, Oduro-Kwarteng S, Foppen JW (2018) Microbial groundwater quality status of hand-dug Wells and boreholes in the Dodowa area of Ghana. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15:730. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040730

MacDonald AM, Calow RC (2009) Developing groundwater for secure rural water supplies in Africa. Desalination 248(1–3):546–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2008.05.100

MacDonald AM, Davies J, Calow RC (2008) African hydrogeology and rural water supply. In: Applied groundwater studies in Africa. CRC, Boca Raton, FL, pp 127–148

MacDonald AM, Bonsor HC, Dochartaigh BÉÓ, Taylor RG (2012) Quantitative maps of groundwater resources in Africa. Environ Res Lett 7

MacDonald DMJ, Miller JD, Winterbourn JB, Warnaars TA, Mwebembezi L, Arwat P, Tanywa S (2018) High resolution meteorological data from a network of five stations in Kampala, Uganda. Centre for Environmental Data Analysis. https://doi.org/10.5285/a2a8100c46794985b410ea436f24812a

MacDonald AM, Lark RM, Taylor RG, Abiye T, Fallas HC, Favreau G, Goni IB, Kebede S, Scanlon B, Sorensen JP, Tijani M (2021) Mapping groundwater recharge in Africa from ground observations and implications for water security. Environ Res Lett 16. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abd661

Maidment RI, Grimes DIF, Allan RP, Greatrex H, Rojas O, Leo O (2013) Evaluation of satellite-based and model re-analysis rainfall estimates for Uganda. Meteorol Appl 20:308–317. https://doi.org/10.1002/met.1283

Małoszewski P, Zuber A (1982) Determining the turnover time of groundwater systems with the aid of environmental tracers. 1: models and their applicability. J Hydrol 57:207–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1694(82)90147-0

Maréchal JC, Wyns R, Lachassagne P, Subrahmanyam K (2004) Vertical anisotropy of hydraulic conductivity in the fissured layer of hard-rock aquifers due to the geological patterns of weathering profiles. J Geol Soc India 63. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00458972. Accessed March 2022

Matiatos I, Wassenaar LI, Monteiro LR, Venkiteswaran JJ, Gooddy DC, Boeckx P, Sacchi E, Yue FJ, Michalski G, Alonso-Hernández C, Biasi C (2021) Global patterns of nitrate isotope composition in rivers and adjacent aquifers reveal reactive nitrogen cascading. Commun Earth Environ 2:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00121-x

Maurice L, Taylor RG, Tindimugaya C, MacDonald AM, Johnson P, Kaponda A, Owor M, Sanga H, Bonsor HC, Darling WG, Gooddy D (2019) Characteristics of high-intensity groundwater abstractions from weathered crystalline bedrock aquifers in East Africa. Hydrogeol J 27:459–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-018-1836-9

Mileham L, Taylor R, Thompson J, Todd M, Tindimugaya C (2008) Impact of rainfall distribution on the parameterisation of a soil-moisture balance model of groundwater recharge in equatorial Africa. J Hydrol 359:46–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2008.06.007

Mukherjee A, von Bromssen M, Scanlon BR, Bhattacharya P, Fryar AE, Hasan MA, Ahmed KM, Chatterjee D, Jacks G, Sracek O (2008) Hydrogeochemical comparison and effects of overlapping redox zones on groundwater arsenic near the Western (Bhagirathi sub-basin, India) and eastern (Meghna sub-basin, Bangladesh) margins of the Bengal Basin. J Contam Hydrol 99:31–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2007.10.005

Murungi C, Blokland MW (2016) Assessment of tools in use by the National Water and sewerage corporation to improve water and sanitation services to the slums of Kampala, Uganda. Int J Water 10:192–212. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJW.2016.075568