Abstract

Previous studies suggested that a polymorphism in the dopamine transporter gene (SLC6A3) is associated with nicotine dependence and age of smoking onset, but the conclusion was controversial. To detect the association of a G→A polymorphism (NCBI dbSNP cluster ID: rs27072) in 3’-untranslated region of the SLC6A3 with nicotine dependence and early smoking onset, we recruited 253 sibships including 668 nicotine-dependent siblings from a rural district of China. The sibship disequilibrium tests (SDT) showed that the rs27072-A allele is significantly associated with smoking onset ≤18 years (ϰ2=9.78, p=0.003 in severely nicotine-dependent smokers, and ϰ2=4.24, p=0.058 in total smokers), but not significantly associated with severe nicotine dependence. Conditional logistic regression showed that the risk of early smoking onset by the rs27072-A allele was almost three times greater in severely nicotine-dependent smokers [Odds ratio (OR)=11.3, 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.5–85.6] than that in total smokers. Linear regression showed that rs27072-A allele also increased the risk of nicotine dependence by early smoking onset compared with homozygous rs27072-G genotype. Although these findings are preliminary and need validation, the results suggest that a polymorphism in the SLC6A3 may play important roles in smoking onset, and there may be an interactive effect between the SLC6A3 and early smoking onset on modulating the susceptibility of nicotine dependence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nicotine dependence is a psychoactive substance-use disorder caused by repetitive self-administration of nicotine, mainly by continuous cigarette smoking (Moxham 2000; Leshner 1997). It is a complex, multifactorial behavior with both genetic and environmental determinants (Hall et al. 2002). To address the etiology of nicotine dependence, it is important to consider the interactive effect of genetic and environmental factors (Yoshimasu and Kiyohara 2003). The age of smoking onset, which is associated with nicotine dependence (Breslau et al. 1993), is also influenced by genetic factors (Hall et al. 2002). The previous study suggested that the genetic component of smoking onset is estimated to contribute 37% of the variance in male adults and 55% in female adults (Li et al. 2003).

The key biological substrate of nicotine dependence was shown to be the mesolimbic dopaminergic system where nicotine can activate the brain reward system by stimulating dopamine release (Pich et al. 1997). Dopamine transporter, a transmembrane protein involved in the reuptake of released dopamine to presynaptic terminals, is an important functional modulator of dopaminergic system in the brain, and it plays a crucial role in a reinforcing-rewarding effect during drug dependence (Chen and Reith 2000). The dopamine transporter gene (SLC6A3) is associated with several drug dependence, including cocaine, amphetamine, and alcoholism (Amara and Sonders 1998). A variable number of tandem repeat (VNTR) polymorphisms in 3’-untranslated region (3’-UTR) of the SLC6A3 was shown to be associated with some smoking behaviors. SLC6A3–9 allele carriers were less likely to initiate smoking before 16 years (Lerman et al. 1999), but some reports failed to confirm this association (Sabol et al. 1999; Jorm et al. 2000). The present study investigated the association of a G→A polymorphism (NCBI dbSNP cluster ID: rs27072) in 3’-UTR of the SLC6A3 with early smoking onset and nicotine dependence in 668 smokers from 253 Chinese sibships.

Materials and methods

Subjects

We recruited families from a rural district in Huoqiu County, China from November 2000 to July 2001. We used a Chinese translation of the standardized Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (Heatherton et al. 1991) as a measure of severe nicotine dependence, which was defined as a score of eight or more on the FTND (Fagerstrom et al. 1990). The Chinese-translated FTND was previously validated in a Chinese population (Niu et al. 2000). Our survey team screened all probands and their available siblings using the FTND, and trained investigators interviewed all subjects from enrolled families using a detailed questionnaire covering sociodemographic characteristics, current and previous smoking phenotypes, and medical and psychological conditions. A total of 668 smokers aged from 22 to 78 were collected from 253 sibships, including 508 severe nicotine-dependent smokers (FTND≥8) and 160 not severely nicotine-dependent smokers (FTND≤7). Each subject provided 30 ml of venous blood for genomic DNA extraction. The institutional review board of the Harvard School of Public Health approved our protocols, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted according to a standard method (Buffone and Darlington 1985). The PCR-RFLP method was used to genotype the rs27072 polymorphism. The forward and reverse primers flanking the marker locus are 5’-GTAGATCTGTGCAGCGAGGT-3’ and 5’-CTACTGTGAGCACGGGGATT-3’ respectively. A total volume of 6 μl PCR reaction contains 30 ng genomic DNA, 1×PCR buffer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), 250 μM MgCl2, 200 μM mixed dNTP, 240 nM forward and reverse primers respectively, 0.135 U Taq DNA polymerase (QIAGEN, CA, USA), and 0.12 μl glycerin, covered by 8 μl paraffin oil. The PCR reaction begins with denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, follows by 34 cycles of 95°C for 45 s, 59°C for 45 s, 72°C for 45 s, and final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products (200 bp) were digested by 4 U of MspI (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA, USA) at 37°C for 12 h. Digested products were separated by 2% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide under ultraviolet illumination. The different alleles were distinguishable with single 200 bp fragment for the rs27072-A allele and two fragments of 107bp+93 bp for the rs27072-G allele.

Statistical analysis

SAS statistical program (Release 8.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for the analyses, which were conducted in several stages. First, we performed descriptive analyses to calculated mean value and standard deviation (SD) for age, height, weight, age of smoking onset and FTND score, and prevalence of severe nicotine dependence (FTND≥8), early smoking onset (≤18 years), gender, marital status (married, single, and others), education (≤9 years and >9 years), socioeconomic status (farmers and nonfarmers) and genotypes (GG, AG and AA) in all participants. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium of the rs27072 genotypes was examined in our sample using a ϰ2 test with randomly selecting one subject from each sibship. We ruled out six outliners who had smoking onset before 8 years or after 42 years in examination of the association between rs27072 genotypes and early smoking onset.

Second, we used the sibship disequilibrium tests (SDT) (Horvath and Laird 1998) in total smokers and in severely nicotine-dependent smokers (FTND≥8) respectively to examine the association between the rs27072-A allele and early smoking onset. The preference of the rs27072-A allele transmitted to case siblings of early smoking onset ≤18 years (25th percentile of age of smoking onset as a cutoff) in all of the discordant sibships was compared with the preference of the rs27072-A allele transmitted to control siblings of late smoking onset (>18 years) in all of the discordant sibships, and an exact P value was calculated according to the instruction by Horvath and Laird (1998). The association between the rs27072-A allele and severe nicotine dependence (FTND≥8) was also detected by the SDT analysis.

Third, the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to test for association of genotypes and early smoking onset by conditional logistic regression (Siegmund et al. 2000) in total smokers and severely nicotine-dependent smokers (FTND≥8) respectively. Statistic significance (P value) was adjusted for residual correlation within sibships by the robust variance estimate for the regression coefficient (Siegmund et al. 2000). We presented the OR without (crude estimate) and with (adjusted estimate) adjustment for some potential confounding factors such as age, height, gender and education by multiple conditional logistic regression.

Fourth, the association between the means of FTND scores and the means of age of smoking onset was examined by linear regression in smokers with and without the rs27072-A allele respectively. The intraclass correlation within sibships was controlled by generalized estimating equations (GEE) (Zeger and Liang 1986) in the linear regression models. The regression coefficient was obtained without (crude estimate) and with (adjusted estimate) adjustment for potential confounding factors from age, height, weight, gender, marital status, education, and socioeconomic status. The potential confounding factors that were significant at P≤0.1 in univariate linear regression (potential association with the level of nicotine dependence, age of smoking onset, or genotypes) were entered simultaneously into the multiple regressions.

Results

The characteristics of study participants included in this analysis are summarized in Table 1. Mean age was 46.8 years, and 98.7% of the participants were male. Most participants were low educated with low socioeconomic status, 76.1% of the participants were severely nicotine dependent. In total smoking siblings, 24.2% had early smoking onset, which was defined as age of smoking onset ≤ 18 years. The frequency of the rs27072-A allele in total siblings was 23.7%. In a random sample (n=253) with one sibling from each sibship, the distribution of rs27072 genotypes did not deviate from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (ϰ2=0.01, p>0.9).

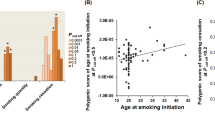

No significant association was detected between the rs27072-A allele and severe nicotine dependence (FTND≥8) by SDT (ϰ2=0.56, P=0.551). However, the rs27072-A allele was associated with smoking onset ≤18 years (ϰ2=4.24, P=0.058 in total smokers and ϰ2=9.78, P=0.003 in severely nicotine-dependent smokers). The conditional logistic regression of early smoking onset ≤18 years with rs27072 genotypes confirmed the results from SDT analyses. Additionally, the odds ratio in severely nicotine-dependent smokers (OR=11.3, 95%CI=1.5–85.6, P=0.038) was 2.8-fold greater than that in total smokers (OR=4.0, 95%CI=1.0–15.6, P=0.022, Table 2) after adjustment for age, height, gender, and education. When stratified with rs27072-A allele carriers and noncarriers, linear regression showed that the regression coefficient (β) of age of smoking onset on levels of nicotine dependence in carriers (β=−0.124, SE=0.034, P<0.01) was 2.0-fold greater than that in noncarriers (β=−0.063, SE=0.021, P<0.01, Table 3) after adjustment for age, height, gender, education, and intraclass correlation within sibships.

Discussion

Our study revealed that the rs27072 polymorphism in 3’-UTR of the SLC6A3 was significantly associated with early smoking onset. In particular, rs27072-A allele carriers were more likely to initiate smoking before 18 years. Additionally, the risk of nicotine dependence from early smoking onset was significantly greater in rs27072-A allele carriers than that in noncarriers. Compared with total smokers, severity of nicotine dependence also increased the OR of early smoking onset by the high-risk rs27072-A allele. These findings suggested that there exists an interaction between early smoking onset and a polymorphism in the SLC6A3 in modulating the susceptibility of nicotine dependence, although no significant association between the rs27072-A allele and severe nicotine dependence was found in our sample.

For common multifactorial diseases, most of the susceptibility genes do not have a primary etiological role in predisposition to disease, but rather, act as response modifiers to exogenous factors from the environment (Tiret 2002). The present study showed that the rs27072 genotype is a risk factor of early smoking onset and the later is a risk factor of the susceptibility of nicotine dependence. Furthermore the high-risk rs27072 genotype exacerbates the effect of early smoking onset on the susceptibility of nicotine dependence. The pattern of the interactive effect of the rs27072 genotype and early smoking onset was synergistic on modulating the susceptibility of nicotine dependence, which confirms to one of the gene-environment interaction models (model A and B) described by Ottman (1996).

Lerman et al. (1999) reported that a VNTR polymorphism in 3’-UTR of the SLC6A3 was associated with early smoking onset, in which SLC6A3–9 allele carriers were shown to be less likely to initiate smoking before 16 years. In addition, a previous study in Japanese population showed that the SLC6A3-9 allele was in linkage disequilibrium with the rs27072-G allele, and the haplotype of SLC6A3–10 and rs27072-A was associated with alcoholism (Ueno et al. 1999). Although the linkage disequilibrium between the rs27072 and the VNTR has not been verified in a Chinese population, these findings together suggested that polymorphisms in the dopamine transporter gene might be important to influence the genetic susceptibility of smoking onset and nicotine dependence.

For some complex traits, such as arthritis, hypertension, dementia, and diabetes, the sign of early onset usually indexes the at-risk population, and the early onset traits often have a substantial genetic component. The same is true for nicotine dependence (Tyndale and Sellers 2002). Early smoking onset was an important aspect of the vulnerability of nicotine addiction (Breslau et al. 1993; Kessler 1995; Niu et al. 2000), which also was shown in the present study. Some reports indicated that genetic factors influenced smoking onset and those that influenced nicotine dependence were not perfectly correlated (Kendler et al. 1999; Sullivan et al. 2001; Batra et al. 2003). The present study did not obtain a direct significant association between the rs27072-A allele and severe nicotine dependence. Our results suggested that rs27072-A allele carriers had greater risk than noncarriers to acquire nicotine dependence if smoking began at an early age. Both the single nucleotide polymorphism and the VNTR polymorphism in 3’-UTR of the SLC6A3 may affect gene expression (Miller and Madras 2002). Based on the important role of dopamine transporter in the brain reward system, we hypothesized that possible modification of gene expression by polymorphisms may affect individual smoking sensitivity, and the later may further influence one’s smoking initiation.

This study had several advantages. We used the SDT and conditional logistic regression, both of which can exclude spurious associations caused by population stratification. Our study population was homogeneous with regard to lifestyle, social/cultural norms, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity. Meanwhile, our results from conditional logistic and linear regression were adjusted for some potential confounding factors from sociodemography, such as age, height, gender, and education. No subjects in this study used nicotine replacement therapies, thus the potential confounding by drug interventions was eliminated.

In summary, the present study showed significant associations between the rs27072-A allele in the SLC6A3 and early smoking onset in a Chinese population. The rs27072-A allele increased the risk of the severity of nicotine dependence by early smoking onset, and severe nicotine dependence also increased the risk of early smoking onset by the high-risk rs27072-A allele. Together with some previous findings, our results suggest that polymorphisms in the SLC6A3 might play an important role in influencing the genetic susceptibility of smoking onset. The present study also provided preliminary evidence of an interactive effect of the SLC6A3 and early smoking onset on modulating the susceptibility of nicotine dependence, although these findings need validation with large samples and in other ethnic populations.

Reference

Amara SG, Sonders MS (1998) Neurotransmitter transporters as molecular targets for addictive drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend 51:87–96

Batra V, Patkar AA, Berrettini WH, Weinstein SP, Leone FT (2003) The genetic determinants of smoking. Chest 123:1730–1739

Breslau N, Fenn N, Peterson EL (1993) Early smoking initiation and nicotine dependence in a cohort of young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend 33:129–137

Buffone GJ, Darlington GJ (1985) Isolation of DNA from biological specimens without extraction with phenol. Clin Chem 31:164–165

Chen N, Reith ME (2000) Structure and function of the dopamine transporter. Eur J Pharmacol 405:329–339

Fagerstrom KO, Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT (1990) Nicotine addiction and its assessment. Ear Nose Throat J 69:763–765

Hall W, Madden P, Lynskey M (2002) The genetics of tobacco use: methods, findings and policy implications. Tob Control 11:119–124

Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO (1991) The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict 86:1119–1127

Horvath S, Laird NM (1998) A discordant-sibship test for disequilibrium and linkage: no need for parental data. Am J Hum Genet 63:1886–1897

Jorm AF, Henderson AS, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Korten AE, Rodgers B, Tan X, Easteal S (2000) Association of smoking and personality with a polymorphism of the dopamine transporter gene: results from a community survey. Am J Med Genet 96:331–334

Kendler KS, Neale MC, Sullivan P, Corey LA, Gardner CO, Prescott CA (1999) A population-based twin study in women of smoking initiation and nicotine dependence. Psychol Med 29:299–308

Kessler DA (1995) Nicotine addiction in young people. N Engl J Med 333:186–189

Lerman C, Caporaso NE, Audrain J, Main D, Bowman ED, Lockshin B, Boyd NR, Shields PG (1999) Evidence suggesting the role of specific genetic factors in cigarette smoking. Health Psychol 18:14–20

Leshner AI (1997) Addiction is a brain disease, and it matters. Science 278:45–47

Li MD, Cheng R, Ma JZ, Swan GE (2003) A meta-analysis of estimated genetic and environmental effects on smoking behavior in male and female adult twins. Addiction 98:23–31

Miller GM, Madras BK (2002) Polymorphisms in the 3’-untranslated region of human and monkey dopamine transporter genes affect reporter gene expression. Mol Psychiatry 7:44–55

Moxham J (2000) Nicotine addiction. BMJ 320:391–392

Niu T, Chen C, Ni J, Wang B, Fang Z, Shao H, Xu X (2000) Nicotine dependence and its familial aggregation in Chinese. Int J Epidemiol 29:248–252

Ottman R (1996) Gene-environment interaction: definitions and study designs. Prev Med 25:764–770

Pich EM, Pagliusi SR, Tessari M, Talabot-Ayer D, Hooft van Huijsduijnen R, Chiamulera C (1997) Common neural substrates for the addictive properties of nicotine and cocaine. Science 275:83–86

Sabol SZ, Nelson ML, Fisher C, Gunzerath L, Brody CL, Hu S, Sirota LA, Marcus SE, Greenberg BD, Lucas FR 4th, Benjamin J, Murphy DL, Hamer DH (1999) A genetic association for cigarette smoking behavior. Health Psychol 18:7–13

Siegmund KD, Langholz B, Kraft P, Thomas DC (2000) Testing linkage disequilibrium in sibships. Am J Hum Genet 67:244–248

Sullivan PF, Jiang Y, Neale MC, Kendler KS, Straub RE (2001) Association of the tryptophan hydroxylase gene with smoking initiation but not progression to nicotine dependence. Am J Med Genet 105:479–484

Tiret L (2002) Gene-environment interaction: a central concept in multifactorial diseases. Proc Nutr Soc 61:457–463

Tyndale RF, Sellers EM (2002) Genetic variation in CYP2A6-mediated nicotine metabolism alters smoking behavior. Ther Drug Monit 24:163–171

Ueno S, Nakamura M, Mikami M, Kondoh K, Ishiguro H, Arinami T, Komiyama T, Mitsushio H, Sano A, Tanabe H (1999) Identification of a novel polymorphism of the human dopamine transporter (DAT1) gene and the significant association with alcoholism. Mol Psychiatry 4:552–557

Yoshimasu K, Kiyohara C (2003) Genetic influences on smoking behavior and nicotine dependence: a review. J Epidemiol 13:183–92

Zeger SL, Liang KY (1986) Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 42:121–130

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIDA grant 1R01-DA-12905. We wish to acknowledge the assistance and cooperation of the faculty and staff of the Anhui Medical University Biomedical Institute and thank our subjects for participating in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ling, D., Niu, T., Feng, Y. et al. Association between polymorphism of the dopamine transporter gene and early smoking onset: an interaction risk on nicotine dependence. J Hum Genet 49, 35–39 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10038-003-0104-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10038-003-0104-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association studies of dopamine synthesis and metabolism genes with multiple phenotypes of heroin dependence

BMC Medical Genetics (2020)

-

Converging findings from linkage and association analyses on susceptibility genes for smoking and other addictions

Molecular Psychiatry (2016)

-

Modeling complex genetic and environmental influences on comorbid bipolar disorder with tobacco use disorder

BMC Medical Genetics (2010)

-

Common and Unique Biological Pathways Associated with Smoking Initiation/Progression, Nicotine Dependence, and Smoking Cessation

Neuropsychopharmacology (2010)

-

Dopamine Genes and Nicotine Dependence in Treatment-Seeking and Community Smokers

Neuropsychopharmacology (2009)