Abstract

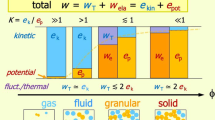

Soft, disordered, micro-structured materials are ubiquitous in nature and industry, and are different from ordinary fluids or solids, with unusual, interesting static and flow properties. The transition from fluid to solid—at the so-called jamming density—features a multitude of complex mechanisms, but there is no unified theoretical framework that explains them all. In this study, a simple yet quantitative and predictive model is presented, which allows for a changing jamming density, encompassing the memory of the deformation history and explaining a multitude of phenomena at and around jamming. The jamming density, now introduced as a new state-variable, changes due to the deformation history and relates the system’s macroscopic response to its micro-structure. The packing efficiency can increase logarithmically slow under gentle repeated (isotropic) compression, leading to an increase of the jamming density. In contrast, shear deformations cause anisotropy, changing the packing efficiency exponentially fast with either dilatancy or compactancy as result. The memory of the system near jamming can be explained by a micro-statistical model that involves a multiscale, fractal energy landscape and links the microscopic particle picture to the macroscopic continuum description, providing a unified explanation for the qualitatively different flow-behavior for different deformation modes. To complement our work, a recipe to extract the history-dependent jamming density from experimentally accessible data is proposed, and alternative state-variables are compared. The proposed simple macroscopic constitutive model is calibrated from particles simulation data, with the variable jamming density—resembling the memory of microstructure—as essential novel ingredient. This approach can help understanding predicting and mitigating failure of structures or geophysical hazards, and will bring forward industrial process design and optimization, and help solving scientific challenges in fundamental research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Granular materials are a special case of soft-matter with micro-structure, as also foams, colloidal systems, glasses, or emulsions [1–3]. Particles can flow through a hopper or an hour-glass when shaken, but jam (solidify) when the shaking stops [4]. These materials jam above a “certain” volume fraction, or jamming density, referred to as the “jamming point” or “jamming density” [3, 5–23], and become mechanically stable with finite bulk- and shear-moduli [8, 9, 12, 15, 24–27]. Notably, in the jammed state, these systems can “flow” by reorganizations of their micro-structure [28, 29]. Around the jamming transition, these systems display considerable inhomogeneity, such as reflected by over-population of weak/soft/slow mechanical oscillation modes [11], force-networks [10, 30, 31], diverging correlation lengths and relaxation time-scales [9, 13, 22, 32–35], and some universal scaling behaviors [36, 37]. Related to jamming, but at all densities, other phenomena occur, like shear-strain localization [12, 16, 38–40], anisotropic evolution of structure and stress [7, 9, 11, 13, 30, 31, 38–46], and force chain inhomogeneity [7, 19, 28]. To gain a better understanding of the jamming transition concept, one needs to consider both the structure (positions and contacts) and contact forces. Both of them illustrate and reflect the transition, e.g., with a strong force chain network percolating the full system and thus making unstable packings permanent, stable and rigid [7, 19, 47–49].

For many years, scientists and researchers have considered the jamming transition in granular materials to occur at a particular volume fraction, \(\phi _J\) [50]. In contrast, over the last decade, numerous experiments and computer simulations have suggested the existence of a broad range of \(\phi _J\), even for a given material. It was shown that the critical density for the jamming transition depends on the preparation protocol [12, 18, 22, 23, 36, 51–58], and that this state-variable can be used to describe and scale macroscopic properties of the system [26]. For example, rheological studies have shown that \(\phi _J\) decreases with increasing compression rate [8, 57, 59, 60] (or with increasing growth rate of the particles), with the critical scaling by the distance from the jamming point (\(\phi - \phi _J\)) being universal and independent of \(\phi _J\) [20, 36, 51, 61, 62] Recently, the notion of an a-thermal isotropic jamming “point” was challenged due to its protocol dependence, suggesting the extension of the jamming point, to become a J-segment [42, 60, 63, 64]. Furthermore, it was shown experimentally, that for a tapped, unjammed frictional 2D systems, shear can jam the system (known as “shear jamming”), with force chain networks percolating throughout the system, making the assemblies jammed, rigid and stable [7, 29, 47, 48, 65, 66], all highlighting a memory that makes the structure dependent on history H. But to the best of our knowledge, quantitative characterization of the varying/moving/changing transition points, based on H, remains a major open challenge.

1.1 Application examples

In the fields of material science, civil engineering and geophysics, the materials behave highly hysteretic, non-linear and involve irreversibility (plasticity), possibly already at very small deformations, due to particle rearrangements, more visible near the jamming transition [67–70]. Many industrial and geotechnical applications that are crucial for our society involve structures that are designed to be far from failure (e.g. shallow foundations or underlying infrastructure), since the understanding when failure and flow happens is not sufficient, but is essential for the realistic prediction of ground movements [71]. Finite-element analyses of, for example tunnels, depend on the model adopted for the pre-failure soil behavior; when surface settlement is considered, the models predicting non-linear elasticity and history dependence become of utmost importance [72]. Design and licensing of infrastructure such as nuclear plants and long span bridges are dependent on a robust knowledge of elastic properties in order to predict their response to seismic ground motion such as the risk of liquefaction and the effect of the presence of anisotropic strata. (Sediments are one example of anisotropic granular materials of particles of organic or inorganic origin that accumulate in a loose, unconsolidated form before they are compacted and solidified. Knowing their mechanical behavior is important in industrial, geotechnical and geophysical applications. For instance, the elastic properties of high-porosity ocean-bottom sediments have a massive impact on unconventional resource exploration and exploitation by ocean drilling programs.)

When looking at natural flows, a complete description of the granular rheology should include an elastic regime [73], and the onset of failure (flow or unjamming) deserves particular attention in this context. The material parameters have a profound influence on the computed deformations prior to failure [74, 75], as the information on the material state is usually embedded in the parameters. Likewise, also for the onset of flow, the state of the material is characterized by the value of the macroscopic friction angle, as obtained, e.g., from shear box experiments or tri-axial tests. Since any predictive model must describe the pre-failure deformation [76] as well as the onset of flow (unjamming) of the material, many studies have been devoted to the characteristics of geomaterials (e.g., tangent moduli, secant moduli, peak strength) and to the post-failure regime [77] or the steady (critical) state flow rheology, see Refs. [40, 78] and references therein.

1.2 Approach of this study

Here, we consider frictionless sphere assemblies in a periodic system, which can help to elegantly probe the behavior of disordered bulk granular matter, allowing to focus on the structure [3], without being disturbed by other non-linearities [7, 29, 79] (as e.g. friction, cohesion, walls, environmental fluids or non-linear interaction laws). For frictionless assemblies, it is often assumed that the influence of memory is of little importance, maybe even negligible. If one really looks close enough, however, its relevance becomes evident. We quantitatively explore its structural origin in systems where the re-arrangements of the micro-structure (contact network) are the only possible mechanisms leading to the range of jamming densities (points), i.e. a variable state-variable jamming density.

In this study, we probe the jamming transition concept by two pure deformation modes: isotropic compression or “tapping” and deviatoric pure shear (volume conserving), which allow us to combine the J-segment concept with a history dependent jamming density.Footnote 1 Assuming that all other deformations can be superimposed by these two pure modes, we coalesce the two concepts of isotropic and shear induced jamming, and provide the unified model picture, involving a multiscale, fractal-type energy landscape [18, 80–82]; in general, deformation (or the preparation procedure) modify the landscape and its population; considering only changes of the population already allows to establish new configurations and to predict their evolution. The observations of different \(\phi _J\) of a single material require an alternative interpretation of the classical “jamming diagram” [5].

Our results will provide a unified picture, including some answers to the open questions from literature: (i) What lies in between the jammed and flowing (unjammed) regime? As posed by Ciamarra et al. [63]. (ii) Is there an absolute minimum jamming density? As posed by Ciamarra et al. [63]. (iii) What protocols can generate jammed states? As posed by Torquato et al. [56]. (iv) What happens to the jamming and shear jamming regime in 3D and is friction important to observe it? As posed by Bi et al. [7]. Eventually, accepting the fact that the jamming density is changing with deformation history, significant improvement of continuum models is expected, not only for classical elasto-plastic or rheology models, but also, e.g., for anisotropic constitutive models [41, 69, 83, 84], GSH rate type models [85, 86], Cosserat micro-polar or hypoplastic models [87–89] or continuum models with a length scale and non-locality [90, 91]. For this purpose we provide a simple (usable) analytical macro/continuum model as generalization of continuum models by adding one isotropic state-variable. Only allowing \(\phi _J(H)\) to be dependent on history H [64, 92], as key modification, explains a multitude of reported observations and can be significant step forward to solve real-world problems in e.g. electronic industry related novel materials, geophysics or mechanical engineering.

Recent works showed already that, along with the classical macroscopic properties (stress and volume fraction), the structural anisotropy is an important [41, 45, 46, 93–96] state-variable for granular materials, as quantified by the fabric tensor [43, 69] that characterizes, on average, the geometric arrangement of the particles, the contacts and their network, i.e. the microstructure of the particle packing. Note that the anisotropy alone is not enough to characterize the structure, but also an isotropic state-variable is needed, as is the main message of this study.

1.3 Overview

The paper continues with the simulation method in Sect. 2, before the micromechanical particle- and contact-scale observations are presented in Sect. 3, providing analytical (quantitative) constitutive expressions for the change of the jamming density with different modes of deformation. Section 4 is dedicated to a (qualitative) meso-scale stochastic model that explains the different (slow versus fast) change of \(\phi _J(H)\) for different deformation modes (isotropic versus deviatoric/shear). A quantitative predictive macroscale model is presented in Sect. 5 and verified by comparison with the microscale simulations, before an experimental validation procedure is discussed in Sect. 6 and the paper is summarized and conclusions are given in Sect. 7.

2 Simulation method

Discrete Element Method (DEM) simulations are used to model the deformation behavior of systems with \(N = 9261\) soft frictionless spherical particles with average radius \(\langle r \rangle = 1\) (mm), density \(\rho = 2000\) (kg/m3), and a uniform polydispersity width \(w = r_{\mathrm {max}}/r_{\mathrm {min}}= 3\), using the linear visco-elastic contact model in a 3D box with periodic boundaries [44, 69]. The particle stiffness is \(k = 10^8\) (kg/s2), contact viscosity is \(\gamma = 1\) (kg/s). A background dissipation force proportional to the moving velocity is added with \(\gamma _b= 0.1\) (kg/s). The particle density is \(\rho = 2000\) (kg/m3). The smallest time of contact is \(t_c = 0.2279\) (\(\upmu \)s) for a collision between two smallest sized particles [41].

2.1 Preparation procedure and main experiments

For the preparation, the particles are generated with random velocities at volume (solid) fraction \(\phi =0.3\) and are isotropically compressed to \(\phi _t=0.64\), and later relaxed. From such a relaxed, unjammed, stress free initial state with volume fraction, \(\phi _t= 0.64 < \phi _J\), we compress isotropically further to a maximum volume fraction, \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\), and decompress back to \(\phi _t\), during the latter unloading \(\phi _J\) is identified. This process is repeated over M (100) cycles, which provides different isotropic jamming densities (points) \(\phi _J=:{}^M\phi _{J,i}\), related with \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\) and M (see Sect. 3.1).

Several isotropic configurations \(\phi \), such that \(\phi _t< \phi < {}^1\phi _{J,i}\) from the decompression branch are chosen as the initial configurations for shear experiments. We relax them and apply pure (volume conserving) shear (plane-strain) with the diagonal strain-rate tensor \({{\dot{\varvec{\mathrm E}}}}= \pm {\dot{\epsilon }}_\mathrm {d} \left( -1,1,0\right) \), for four cycles.Footnote 2 The x and y walls move, while the z wall remain stationary. The strain rate of the (quasi-static) deformation is small, \( {\dot{\epsilon }}_\mathrm {d} t_c < 3 \times 10^{-6} \), to minimize transient behavior and dynamic effects.Footnote 3

2.2 Macroscopic (tensorial) quantities

Here, we focus on defining averaged tensorial macroscopic quantities—including strain-, stress- and fabric (structure) tensors—that provide information about the state of the packing and reveal interesting bulk features.

From DEM simulations, one can measure the ‘static’ stress in the system [97] as

average over all the contacts in the volume V of the dyadic products between the contact force \(\mathbf {f}^{c}\) and the branch vector \(\mathbf {l}^{c}\), where the contribution of the kinetic fluctuation energy has been neglected [41, 93]. The dynamic component of the stress tensor is four orders of magnitude smaller than the former and hence its contribution is neglected. The isotropic component of the stress is the pressure \(P= \mathrm {tr}(\varvec{\sigma })/3\).

In order to characterize the geometry/structure of the static aggregate at microscopic level, we will measure the fabric tensor, defined as

where \(V^{\mathcal {P}}\) is the volume relative to particle \({\mathcal {P}}\), which lies inside the averaging volume V, and \(\mathbf {n}^{c}\) is the normal unit branch-vector pointing from center of particle \({\mathcal {P}}\) to contact c [93, 98, 99]. Isotropic part of fabric is \(F_\mathrm {v}= \mathrm {tr}(\mathbf {F})\). The corrected coordination number [7, 41] is \(C^{*}= {M_4}/{N_4},\) where, \(M_4\) is total contacts of the \(N_4\) particles having at least 4 contacts, and the non-rattler fraction is \(f_\mathrm {NR}= N_4/N\). C is the ratio of total non-rattler contacts \(M_4\) and total number of particles N, i.e., \(C=M_4/N = \left( M_4/N_4\right) \left( N_4/N\right) = C^{*}f_\mathrm {NR}\), with corrected coordination number \(C^{*}\) and fraction of non-rattlers \(f_\mathrm {NR}\). The isotropic fabric \(F_\mathrm {v}\) is given by the relation \(F_\mathrm {v}= g_3 \phi C\), as taken from Imole et al. [41], with \(g_3\cong 1.22\) for the polydispersity used in the present work. For any tensor \({\mathrm {\varvec{\mathrm Q}}}\), its deviatoric part can be defined as \( Q_\mathrm {d} = \mathrm {sgn}\left( q_{yy} - q_{xx}\right) \sqrt{ 3 q_{ij}q_{ij}/2}\), where \(q_{ij}\) are the components of the deviator of \({\mathrm {\varvec{\mathrm Q}}}\), and the sign function accounts for the shear direction, in the system considered here, where a more general formulation is given in Ref. [69]. Both pressure \(P\) and shear stress \(\varGamma \) are non-dimensionalized by \({2\langle r \rangle }/{k}\) to give dimensionless pressure p and shear stress \(\uptau \).

3 Micromechanical results

3.1 Isotropic deformation

In this section, we present a procedure to identify the jamming densities and their range. We also show the effect of cyclic over-compression to different target volume fractions and present a model that captures this phenomena.

3.1.1 Identification of the jamming density

When a sample is over-compressed isotropically, the loading and unloading paths are different in pressure \(p\). This difference is most pronounced near the jamming density \(\phi _J\), and for the first cycle. It brings up the first question of how to identify a jamming density, \(\phi _J\). The unloading branch of a cyclic isotropic over-compression along volume fraction \(\phi \) is well described by a linear relation in volumetric strain, with a tiny quadratic correction [44, 100, 101]:

where \(p_0\), \(\gamma _p\), as presented in Table 1, and the jamming density \(\phi _J\) are the fit parameters, and \(-\varepsilon _\mathrm {v}=\log (\phi /\phi _J)\) is the true or logarithmic volumetric strain of the system, defined relative to the reference where \(p\rightarrow 0\), i.e. the jamming volume fraction.

Equation (3), quantifies the scaled stress and is proportional to the dimensionless deformation (overlap per particle size), as derived analytically [100] from the definition of stress and converges to \(p\rightarrow 0\) when \(\phi \rightarrow \phi _J\).

We apply the same procedure for different over-compressions, \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\), and many subsequent cycles M to obtain \({}^M\phi _{J,i}\), for which the results are discussed below. The material parameter \(p_0\) is finite, almost constant, whereas \(\gamma _p\) is small, sensitive to history and contributes mainly for large \(-\varepsilon _\mathrm {v}\), with values ranging around \(0\pm 0.1\); in particular, it is dependent on the over-compression \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\) (data not shown). Unless strictly mentioned, we shall be using the values of \(p_0\) and \(\gamma _p\) given in Table 1.

Figure 1a shows the behavior of \(p\) with \(\phi \) during one full over-compression cycle to display the dependence of the jamming density on the maximum over-compression volume fraction and the number of cycles. With increasing over-compression amplitude, e.g. comparing \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.68\) and \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.82\), the jamming density, as realized after unloading, is increasing. Also, with each cycle, from \(M=1\) to \(M=100\), the jamming density moves to larger values. Note that the difference between the loading and the unloading curves becomes smaller for subsequent over-compressions. Fig. 1b shows the scaled pressure, i.e., \(p\) normalized by \(\phi C/\phi _J\), which removes its non-linear behavior. \(p\) represents the average deformation (overlap) of the particles at a given volume fraction, proportional to the distance from the jamming density \(\phi _J\).Footnote 4 In the small strain region, for all over-compression amplitude and cycles, the datasets collapse on a line with slope \(p_0\sim 0.042\). Only for very strong over-compression, \(-\varepsilon _\mathrm {v}>0.1\), a small deviation (from linear) of the simulation data is observed due to the tiny quadratic correction in Eq. (3).

a Dimensionless pressure \(p\) plotted against volume fraction \(\phi \) and for an isotropic compression starting from \(\phi _t= 0.64\) to \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.68\) (green inverter triangle) and \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.82\) (red bullet) and decompression back to \(\phi _t\) for \(M=1\), leading to \({}^1\phi _J(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.68) = 0.66\) and \({}^1\phi _J(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.82) = 0.6652\). The blue square data points represent cyclic over-compression to \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.82\) for \(M=100\), leading to \({}^{100}\phi _J(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.82) = 0.6692\). The \({}^M\phi _{J,i}\) are extracted using a fit to Eq. (3). The upward arrow the loading path (small symbols) while the downward arrow the unloading path (big symbols). The inset is the zoomed in regime near the jamming density, and lines are just connecting the datasets. b Scaled pressure \(p\phi _J/\phi C\) plotted against volumetric strain \(-\varepsilon _\mathrm {v}=\log (\phi /\phi _J)\) for the same simulations as a. Lines The scaled pressure, when Eq. (3) is used, with different \(\gamma _p = -0.1, 0.07\) and \(-0.01\) for green, red and blue lines respectively. The inset is the zoomed in regime for small \(-\varepsilon _\mathrm {v}\) (color figure online)

a Evolution of isotropic jamming densities \({}^M\phi _{J,i}\) after performing M isotropic compression-decompression cycles up to different maximum volume fractions \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\), as given in the inset. With increasing \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\), the range of the established jamming densities \({}^M\phi _{J,i}=\phi _J(M,\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i)\) increases. The minimum (lower bound) of all \({}^M\phi _{J,i}\) is defined as the critical jamming limit point, \(\phi _{c}= 0.6567\). The solid lines through the data are universal fits to a stretched exponential [104, 106–108] with only one single variable parameter \(\phi _J^{\mathrm {max}}\), i.e., the upper limit jamming density for \(M \rightarrow \infty \), which depends on \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\). b The first jamming density \({}^1\phi _{J,i}\) (blue square) and after many over-compression \({}^{\infty }\phi _{J,i}\) (brown bullet) are plotted against over-compression amplitude \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\). Solid lines represent Eq. (5) for \({}^{\infty }\phi _{J,i}\) and (6) for \({}^1\phi _{J,i}\). The shaded region is the explorable range of jamming densities \({}^M\phi _{J,i}\), denoted as J-segment. The red base line the critical jamming density \(\phi _{c}\) (color figure online)

3.1.2 Isotropic cyclic over-compression

Many different isotropic jamming densities can be found in real systems and—as shown here—also for the simplest model material in 3D [64]. Figure 2a shows the evolution of these extracted isotropic jamming densities \({}^M\phi _{J,i}\), which increase with increasing M and with over-compression \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\), for subsequent cycles M of over-compressions, the jamming density \({}^M\phi _{J,i}\) grows slower and slower and is best captured by a Kohlrausch-Williams-Watts (KWW) stretched exponential relation:

with the three universal “material”-constants \(\phi _{c}= 0.6567\) (Sect. 3.2.2), \(\mu _i =1\), and \(\beta _i=0.3\), the lower limit of possible \(\phi _J\)’s, the relaxation (cycle) scale and the stretched exponent parameters, respectively. Only \({}^{\infty }\phi _{J,i}\), the equilibrium (steady-state or shakedown [102]) jamming density limit (extrapolated for \(M \rightarrow \infty \)), depends on the over-compressions \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\). \(\phi _{c}\) is the critical density in the zero pressure limit without previous history, or after very long shear without temperature (which all are impossible to realize with experiments or simulation–only maybe with energy minimization).

Very little over-compression, \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i \gtrsim \phi _{c}\), does not lead to a significant increase in \(\phi _{J,i}\), giving us information about the lower limits of the isotropic jamming densities achievable by shear, which is the critical jamming density \(\phi _{c}= 0.6567\). With each over-compression cycle, \({}^M\phi _{J,i}\) increases, but for larger M, it increases less and less. This is analogous to compaction by tapping, where the tapped density increases logarithmically slow with the number of taps. The limit value \({}^{\infty }\phi _{J,i}\) with \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\) can be fitted with a simple power law relation:

where the fit works perfect for \(\phi _{c}< \phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i \le 0.9\), with parameters \(\phi _{c}=0.6567\), \(\alpha _\mathrm{max}=0.02\pm 2\,\%\), and \(\beta =0.3\), while the few points for \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i \sim \phi _{c}\) are not well captured. The relation between the limit-value \({}^{\infty }\phi _{J,i}\) and \({}^1\phi _{J,i}\) is derived using Eq. (4):

only by setting \(M=1\), as shown in Fig. 2b, with perfect match. With other words, using a single over-compression, Eq. (6) allows to predict the limit value after first over-compression \({}^1\phi _{J,i}\) (or subsequent over-compression cycles, using appropriate M).

a Snapshots of unjammed, fragile and shear jammed states, when the force networks are percolated in none, one or two, and all the three directions, respectively. Only the largest force network, connecting strong forces, \(f \ge k \langle f \rangle \), with \(k = 2.2\) are shown for the three states for clarity, and hence the white spaces in the background. b Plot of \(C^{*}\) and cluster sizes \(\xi /L\) in the three directions for extension in x- and compression in y-directions against the non-rattler fraction \(f_\mathrm {NR}\), along the loading path for an isotropic unjammed initial state with volume fraction \(\phi =0.6584\) and \(\phi _J\left( \phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.82, M=1\right) =: {}^1\phi _{J,i}= 0.6652 \). The upward arrow indicates direction of loading shear strain

Thus, the isotropic jamming density \(\phi _J\) is not a unique point, not even for frictionless particle systems, and is dependent on the previous deformation history of the system [63, 82, 103], e.g. over-compression or tapping/driving (data not shown). Both (isotropic) modes of deformation lead to more compact, better packed configurations [7, 47, 104]. Considering different system sizes, and different preparation procedures, we confirm that the jamming regime is the same (within fluctuations) for all the cases considered (not shown). All our data so far, for the material used, are consistent with a unique limit density \(\phi _{c}\) that is reached after large strain, very slow shear, in the limit of vanishing confining pressure. Unfortunately this limit is vaguely defined, since it is not directly accessible, but rather corresponds to a virtual stress-free state. The limit density is hard to determine experimentally and numerically as well. Reason is that any slow deformation (e.g. compression from below jamming) also leads to perturbations (like tapping leads to granular temperature): the stronger the system is perturbed, the better it will pack, so that usually \(\phi _J > \phi _{c}\) is established. Repeated perturbations lead to a slow stretched exponential approach to an upper-limit jamming density \(\phi _J\rightarrow \phi _J^{\mathrm {max}}\) that itself increases slowly with perturbation amplitude, see Fig. 2b. The observation of different \(\phi _J\) of a single material, was referred to as J-segment [63, 103], and requires an alternative interpretation of the classical “jamming diagram” [5, 7, 66], giving up the misconception of a single, constant jamming “density”. Note that the J-segment is not just due to fluctuations, but it is due to the deformation history, and with fluctuations superposed. The state-variable \(\phi _J\) varies due to deformation, but possibly has a unique limit value that we denote for now as \(\phi _{c}\). Jammed states below \(\phi _{c}\) might be possible too, but require different protocols [105], or different materials, and are thus not addressed here. Next, we discuss the concept of shear jammed states [7] below \(\phi _J\).

Cluster sizes \({\xi }/L\), \(f_\mathrm {NR}\) (top panel), over three strain cycles (bottom panel) for \(\phi =0.6584\) and jamming density \(\phi _J\left( \phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.82,\right. \) \(\left. M=1\right) =: {}^1\phi _{J,i}= 0.6652\). Dashed horizontal black line represents transition from unjammed to shear jammed states. The cluster sizes are smoothed averages over two past and future snapshots

3.2 Shear deformation

To study shear jamming, we choose several unjammed states with volume fractions \(\phi \) below their jamming densities \({}^1\phi _{J,i}\), which were established after the first compression-decompression cycle, for different history, i.e., various previously applied over-compression to \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\). Each configuration is first relaxed and then subjected to four isochoric (volume conserving) pure shear cycles (see Sect. 2.1).

3.2.1 Shear jamming below \(\phi _J(H)\)

We confirm shear jamming, e.g., by a transition in the coordination number \(C^{*}\), from below to above its isostatic limit, \(C^*_0= 6\), for frictionless grains [13, 31, 38, 41]. This was consistently (independently) reconfirmed by using percolation analysis [7, 30], allowing us to distinguish the three different regimes namely, unjammed, fragile and shear jammed states during (and after) shear [66], as shown in Fig. 3a. We study how the \(k-\)cluster, defined as the largest force network, connecting strong forces, \(f \ge k f_\mathrm {avg}\) [109, 110], with \(k=2.2\), different from \(k=1\) for 2D frictional systems [7], percolates when the initially unjammed isotropic system is sheared. More quantitatively, for an exemplary volume fraction \(\phi \left( \phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.82, M=1\right) = 0.6584\), very close to \(\phi _{c}\), Fig. 3b shows that \(f_\mathrm {NR}\) increases from initially zero to large values well below unity due to the always existing rattlers. The compressive direction percolating network \(\xi _y/L_y \) grows faster than the extension direction network \(\xi _x/L_x \), while the network in the non-mobile direction, \(\xi _z/L_z \), lies in between them. For \(f_\mathrm {NR}>0.82\pm 0.01\), we observe that the growing force network is percolated in all three directions (Fig. 3a), which is astonishingly similar to the value reported for the 2D systems [7]. The jamming by shear of the material corresponds (independently) to the crossing of \(C^{*}\) from the isostatic limit of \(C^*_0=6\), as presented in Fig. 3b.

From this perspective, when an unjammed material is sheared at constant volume, and it jams after application of sufficient shear strain, clearly showing that the jamming density has moved to a lower value. Shearing the system also perturbs it, just like over-compression; however, in addition, finite shear strains enforce shape- and structure-changes and thus allow the system to explore new configurations; typically, the elevated jamming density \(\phi _J\) of a previously compacted system will rapidly decrease and exponentially approach its lower-limit, the critical jamming density \(\phi _{c}\), below which no shear jamming exists. Note that we do not exclude the possibility that jammed states below \(\phi _{c}\) could be achieved by other, special, careful preparation procedures [111].

Next, we present the evolution of the strong force networks in each direction during cyclic shear, as shown in Fig. 4, for the same initial system. After the first loading, at reversal \(f_\mathrm {NR}\) drops below the 0.82 threshold, which indicates the breakage/disappearance of strong clusters, i.e. the system unjams. The new extension direction \(\xi _y/L_y \) drops first with the network in the non-mobile directions, \(\xi _z/L_z \), lying again in between the two mobile direction. With further applied strains, \(f_\mathrm {NR}\) increases and again, the cluster associated with the compression direction grows faster than in the extension direction. For \(f_\mathrm {NR}\) above the threshold, the cluster percolates the full system, leading to shear jammed states again. At each reversal, the strong force network breaks/fails in all directions, and the system gets “soft” or even unjams temporarily. However, the network is rapidly re-established in the perpendicular direction, i.e., the system jams and the strong, anisotropic force network again sustains the load. Note that some systems with volume fraction higher and away from \(\phi _{c}\) can resist shear strain reversal as described and modeled in Sect. 5.1.3.

Scatter plots of isotropic quantities a pressure \(p\), b isotropic fabric \(F_\mathrm {v}\) and deviatoric quantities, c shear stress \(\uptau \), d shear stress ratio \(\uptau /p\), and e deviatoric fabric \(F_\mathrm {d}\) for various \(\phi \) and jamming density \(\phi _J\left( \phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.82, M=1\right) =: {}^1\phi _{J,i}= 0.6652\). Black times symbols represent the initial loading cycle, while the green plus and blue asterisk represent states attained for \(\phi <\phi _J\) and \(\phi >\phi _J\), respectively for the subsequent shear. Cyan bullet and the brown square are states chosen after large strain during loading and unloading shear respectively, and are relaxed. The red and purple lines indicate the critical jamming density \(\phi _{c}= 0.6567\) and the jamming density \({}^1\phi _{J,i}\) respectively (color figure online)

3.2.2 Relaxation effects on shear jammed states

Here, we will discuss the system stability by looking at the macroscopic quantities in the saturation state (after large shear strain), by relaxing them sufficiently long to have non-fluctuating values in the microscopic and macroscopic quantities. Every shear cycle after defining e.g. the \(y-\)direction as the initial active loading direction, has two saturation states, one during loading and, after reversal, the other during unloading. In Fig. 5, we show values attained by the isotropic quantities pressure \(p\), isotropic fabric \(F_\mathrm {v}\) and the deviatoric quantities shear stress \(\uptau \), shear stress ratio \(\uptau /p\), and deviatoric fabric \(F_\mathrm {d}\) for various \(\phi \) given the same initial jamming density \(\phi _J\left( \phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.82, M=1\right) =: {}^1\phi _{J,i}= 0.6652\). Data are shown during cyclic shear as well as at the two relaxed saturation states (averaged over four cycles), leading to following observations:

-

(i)

With increasing volume fraction, \(p\), \(F_\mathrm {v}\) and \(\uptau \) increase, while a weak decreasing trend in stress ratio \(\uptau /p\) and deviatoric fabric \(F_\mathrm {d}\) is observed.

-

(ii)

There is almost no difference in the relaxed states in isotropic quantities, \(p\) and \(F_\mathrm {v}\) for the two directions, whereas it is symmetric about zero for deviatoric quantities, \(\uptau \), \(\uptau /p\), and \(F_\mathrm {d}\). The decrease in pressure during relaxation is associated with dissipation of kinetic energy and partial opening of the contacts to “dissipate” the related part of the contact potential energy. However, \(F_\mathrm {v}\) remains at its peak value during relaxation. It is shown in Sect. 2.2 that \(F_\mathrm {v}= g_3 \phi C\), as taken from Imole et al. [41], with \(g_3\cong 1.22\) for the polydispersity used in the present work. Thus we conclude that the contact structure is almost unchanged and the network remains stable during relaxation, since during relaxation \(\phi \) does not change.

-

(iii)

For small volume fractions, close to \(\phi _{c}\), the system becomes strongly anisotropic in stress ratio \(\uptau /p\), and fabric \(F_\mathrm {d}\) rather quickly, during (slow) shear (envelope for low volume fractions in Fig. 5d, e), before it reaches the steady state [49].

-

(iv)

It is easy to obtain the critical (shear) jamming density \(\phi _{c}\) from the relaxed critical (steady) state pressure \(p\), and shear stress \(\uptau \), by extrapolation to zero, as the envelope of relaxed data in Fig. 5a, c.

Phase diagram and scaling with \(\varvec{\phi _{c}}\) to replace the \(\varvec{{}^M\phi _{J,i}}\)’s. a Phase diagram showing the different states: unjammed, isotropic jammed, shear unjammed, fragile and shear jammed, for one particular case of \(\phi _J\left( \phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.82, M=1\right) =: {}^1\phi _{J,i}= 0.6652\). b Plot of minimum strain needed to jam states prepared from the first over-compression cycle with different \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\), as given in the legend. The inset shows the collapse of the states using a scaled definition that includes distance from both isotropic jamming density \({}^M\phi _{J,i}\) and critical jamming density \(\phi _{c}\), using Eq. (7). We only show data for the states for \(\phi < {}^1\phi _{J,i}\) that after the first isotropic compression decompression cycle jam by applying shear

We use the same methodology presented in Eq. (3) to extract the critical jamming density \(\phi _{c}\). When the relaxed \(p\) is normalized with the contact density \(\phi C\), we obtain \(\phi _{c}= 0.6567 \pm 0.0005\) by linear extrapolation. A similar value of \(\phi _{c}\) is obtained from the extrapolation of the relaxed \(\uptau \) data set, and is consistent with other methods using the coordination number \(C^{*}\), or the energy [112]. The quantification of history dependent jamming densities \(\phi _J(H)\), due to shear complementing the slow changes by cyclic isotropic (over)compression in Eq. (4), is discussed next.

3.3 Jamming phase diagram with history H

We propose a jamming phase diagram with shear strain, and present a new, quantitative history dependent model that explains jamming and shear jamming, but also predicts that shear jamming vanishes under some conditions, namely when the system is not tapped, tempered or over-compressed before shear is applied. Using \({\varepsilon }_{d}\) and \(\phi \) as parameters, Fig. 6a shows that for one initial the history dependent jamming state at \({}^1\phi _{J,i}\), there exist sheared states within the range \(\phi _{c}\le \phi \le \phi _J(H)\), which are isotropically unjammed. After small shear strain they become fragile, and for larger shear strain jam and remain jammed, i.e., eventually showing the critical state flow regime [45, 46], where pressure, shear stress ratio and structural anisotropy have reached their saturation levels and forgotten their initial state (data not shown). The transition to fragile states is accompanied by partial percolation of the strong force network, while percolation in all directions indicates the shear jamming transition. Above jamming, the large fraction of non-rattlers provides a persistent mechanical stability to the structure, even after shear is stopped.

For \(\phi \) approaching \(\phi _{c}\), the required shear strain to jam \({\varepsilon }_{d}^{SJ}\) increases, i.e., there exists a divergence “point” \(\phi _{c}\), where ‘infinite’ shear strain might jam the system, but below which no shear jamming was observed. The closer the (constant) volume fraction \(\phi \) is to the initial \({}^1\phi _{J,i}\), the smaller is \({\varepsilon }_{d}^{SJ}\). States with \(\phi \ge {}^1\phi _{J,i}\) are isotropically jammed already before shear is applied.

Based on the study of many systems, prepared via isotropic over-compression to a wide range of volume fractions \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i \ge \phi _{c}\), and subsequent shear deformation, Fig. 6b shows the strains required to jam these states by applying pure shear. A striking observation is that independent of the isotropic jamming density \({}^1\phi _{J,i}\), all curves approach a unique critical jamming density at \(\phi _{c}\sim 0.6567\) (see Sect. 3.2.2). When all the curves are scaled with their original isotropic jamming density \({}^M\phi _{J,i}\) as \(\phi _{sc}= \left( \phi -\phi _{c}\right) /\left( {}^M\phi _{J,i}-\phi _{c}\right) \) they collapse on a unique master curve

shown in the inset of Fig. 6b, with power \(\alpha =1.37 \pm 0.01\) and shear strain scale \({\varepsilon }_{d}^{0}=0.102 \pm 0.001\) as the fit parameters. Hence, if the initial jamming density \({}^M\phi _{J,i}\) or \(\phi _J(H)\) is known based on the past history of the sample, the shear jamming strain \({\varepsilon }_{d}^{SJ}\) can be predicted.

From the measured shear jamming strain, Eq. (7), knowing the initial and the limit value of \(\phi _J\), we now postulate its evolution under isochoric pure shear strain:

Inserting, \({\varepsilon }_{d}=0\), \({\varepsilon }_{d}={\varepsilon }_{d}^{SJ}\) and \({\varepsilon }_{d}=\infty \) leads to \(\phi _J= {}^M\phi _{J,i}\), \(\phi _J= \phi \) and \(\phi _J= \phi _{c}\), respectively. The jamming density evolution due to shear strain \({\varepsilon }_{d}\) is faster than exponential (since \(\alpha > 1\)) decreasing to its lower limit \(\phi _{c}\). This is qualitatively different from the stretched exponential (slow) relaxation dynamics that leads to the increase of \(\phi _J\) due to over-compression or tapping, see Fig. 7a for both cases.

Relaxation mechanisms and dynamics in an energy landscape due to memory effects. a Evolution of the jamming densities \(\phi _J(H)\) due to isotropic and deviatoric (shear) history H. Solid lines represent isotropic compression decompression cycles for three different \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\), leading to an increase in \(\phi _J(H)\) by slow stretched exponential relaxation, see Eq. (4). Dashed lines represent the much faster decrease in \(\phi _J(H)\) due to shear strain \({\varepsilon }_{d}\), using Eq. (8). b The sketch represents only a very small, exemplary part of the hierarchical, fractal-type energy landscape. The red horizontal line is the (quenched) average, while the dotted horizontal line is the momentary average \(\phi _J(H)\) (of the ensemble of states, where the population is represented by green circles). The blue solid arrows show (slow) relaxation due to perturbations, while the dashed arrows indicate (fast) re-arrangements (re-juvenation) due to finite shear strain. The green dots with their size represent the population after some relaxation, in contrast to a random, quenched population where all similar valleys would be equally populated [81] (color figure online)

4 Meso-scale stochastic slow dynamics model

The last challenge is to unify the observations in a qualitative model that accounts for the changes in the jamming densities for both isotropic and shear deformation modes. Over-compressing a soft granular assembly is analogous to small-amplitude tapping [21, 47, 104] of more rigid particles, in so far that both methods lead to more compact (efficient) packing structures, i.e., both representing more isotropic perturbations, rather than shear, which is deviatoric (anisotropic) in nature. These changes are shown in Fig. 2a, where the originally reported logarithmically slow dynamics for tapping [107, 108, 113] is very similar to our results that are also very slow, with a stretched exponential behavior; such slow relaxation dynamics can be explained by a simple Sinai-Diffusion model of random walkers in a random, hierarchical, fractal, free energy landscape [106, 114] in the (a-thermal) limit, where the landscape does not change—for the sake of simplicity.

The granular packing is represented in this picture by an ensemble of random walkers in (arbitrary) configuration space with (potential) energy according to the height of their position on the landscape. (Their average energy corresponds to the jamming density and a decrease in energy corresponds to an increase in \(\phi _J(H)\), thus representing the “memory” and history dependence with protocol H.) Each change of the ensemble represents a rearrangement of packing and units in ensemble represent sub-systems. Perturbations, such as tapping with some small-amplitude (corresponding to “temperature”) allow the ensemble to find denser configurations, i.e., deeper valleys in the landscape, representing larger (jamming) densities [22, 82]. Similarly, over-compression is squeezing the ensemble “down-hill”, also leading to an increase of \(\phi _J\), as presented in Fig. 7b. Larger amplitudes will allow the ensemble to overcome larger barriers and thus find even deeper valleys. Repetitions have a smaller chance to do so—since the easy reorganizations have been realized previously—which explains the slow dynamics in the hierarchical multiscale structure of the energy landscape.

Schematic sketch of the evolution of the system in stress-density space, e.g., pressure, a starting from a state (point) slightly above jamming, under b isotropic compression, and c further compression, the system reaches a higher stress level, while the jamming density moves to the right (larger densities). d For isotropic decompression (extension) the system reduces pressure and the jamming density remains (almost) constant, until for e ongoing decompression, the system unjams and reaches a density below the jamming density. (For tapping (not shown), the density of the system would remain fixed, the jamming density would increase for ongoing perturbations, so that the stress would reduce and the system could even unjam if the density is low enough.)

Schematic sketch of the evolution of the system under isochoric (volume conserving, represented by the dashed vertical red line) shear in stress-density space, think of shear stress, which is just proportional to pressure, a starting from the state (point Fig. 8e) slightly below jamming, which was previously over-compressed. Under shear b the jamming density shifts to the left until it reaches the actual density, at which c shear jamming kicks in, i.e., stress increases above zero. From this state, for d shear reversal, the jamming density moves to the right again and the system can unjam. For ongoing shear, e at a higher density, at finite granular temperature \(T_g\), the jamming density is increased by the perturbations due to \(T_g\) while shear, at the same time, decreases the jamming density, as indicated by the two arrows, which resembles a steady state. A change of either shear rate or temperature will then lead to either transient shear-thickening or shear-thinning, before a new steady state path is reached

In contrast to the isotropic perturbations, where the random walkers follow the “down-hill” trend, shear is anisotropic and thus pushing parts of the ensemble in “up-hill’ direction’. For example, under planar simple shear, one (eigen) direction is extensive (up-hill) whereas an other is compressive (down-hill). If the ensemble is random, shear will only re-shuffle the population. But if the material was previously forced or relaxed towards the (local) land-scape minima, shear can only lead to a net up-hill drift of the ensemble, i.e., to decreasing \(\phi _J\), referred to as dilatancy under constant stress boundary conditions.

For ongoing over-compression, both coordination number and pressure slowly increase, as sketched in Fig. 8, while the jamming density drifts to larger values due to re-organization events that make the packing more effective, which moves the state-line to the right (also shown in Fig. 7a). For decompression, we assume that there are much less re-organization events happening, so that the pressure moves down on the state-line, until the system unjams. For ongoing perturbations, at constant volume, as tapping or a finite temperature, \(T_g\), both coordination number and pressure slowly decrease (data not shown), whereas for fixed confining pressure the volume would decrease (compactancy, also not shown).

For ongoing shear, the coordination number, the pressure and the shear stress increase, since the jamming density decreases, as sketched in Fig. 9 until a steady state is reached. This process is driven by shear strain amplitude and is much faster than the relaxation dynamics. For large enough strain the system will be sufficiently re-shuffled, randomized, or “re-juvenated” such that it approaches its quenched, random state close to \(\phi _{c}\) (see Fig. 7a).

If both mechanisms, relaxation by temperature, and continuous shear are occurring at the same time, one can reach another (non)-“equilibrium” steady state, where the jamming density remains constant, balancing the respective increasing and decreasing trends, as sketched in Fig. 9e.

5 Macroscopic constitutive model

In this section, we present the simplest model equations, as used for the predictions, involving a history dependent \(\phi _J(H)\), as given by Eq. (4) for isotropic deformations and Eq. (8) for shear deformations. The only difference to Imole et al. [41], where these relations are taken from, based on purely isotropic unloading, is the variable \(\phi _J= \phi _J(H)\).

5.1 Presentation and model calibration

5.1.1 During cyclic isotropic deformation

During (cyclic) isotropic deformation, the evolution equation for the corrected coordination number \(C^{*}\) is:

with \(C_0=6\) for the frictionless case and parameters \(C_1\) and \(\theta \) are presented in Table 1. The fraction of non-rattlers \(f_\mathrm {NR}\) is given as:

with parameters \(\varphi _c\) and \(\varphi _v\) presented in Table 1. We modify Eq. (3) for the evolution of \(p\) together with the history dependent \(\phi _J=\phi _J(H)\) so that,

with parameters \(p_0\) and \(\gamma _p\) presented in Table 1, and the true or logarithmic volume change of the system is \(-\varepsilon _\mathrm {v} = \log (\phi /\phi _J(H))\), relative to the momentary jamming density. The non-corrected coordination number is \(C = C^{*}f_\mathrm {NR}\), as can be computed using Eqs. (9) and (10). Also the parameters \(C_1\), \(\theta \) for \(C^{*}\), \(\varphi _c\), \(\varphi _v\) for \(f_\mathrm {NR}\), and \(p_0\), \(\gamma _p\) for pressure p are similar to Imole et al. [41], with the second order correction parameter \(\gamma _p\) most sensitive to the details of previous deformations; however, not being very relevant since it is always a small correction due to the product \(\gamma _p (-\varepsilon _\mathrm {v})\).

The above relations are used to predict the behavior of the isotropic quantities: dimensionless pressure \(p\) and coordination number \(C^{*}\), during cyclic isotropic compression, as well as for the fraction of non-rattlers for cyclic shear, with corresponding parameters presented in Table 1. Note that during isotropic deformation, \(\phi _J(H)\) was changed only during the compression branch, using Eq. (4) for fixed \(M=1\) using \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\) as variable, but is kept constant during unloading/expansion.

The above relations are used to predict the behavior of the isotropic quantities: dimensionless pressure \(p\) and coordination number \(C^{*}\), by only adding the history dependent jamming density \(\phi _J(H)\) to the constitutive model, as tested below in Sect. 5.2.

5.1.2 Cyclic (pure) shear deformation

During cyclic (pure) shear deformation, a simplified equation for the shear stress ratio \(\uptau /p\) is taken from Imole et al. [41], where the full model was introduced as rate-type evolution equations, and further calibrated and tested by Kumar et al. [69]:

with \(\left( \uptau /p\right) ^{\mathrm {0}}\) and \(\left( \uptau /p\right) ^{\mathrm {max}}\) the initial and maximum (saturation) shear stress ratio, respectively, and \(\beta _s\) its growth rate.Footnote 5 Similarly, a simplified equation for the deviatoric fabric \(F_\mathrm {d}\) can be taken from Refs. [41, 69] as:

with \({F_\mathrm {d}}^{\mathrm {0}}\) and \({F_\mathrm {d}}^{\mathrm {max}}\) the initial and maximum (saturation) values of the deviatoric fabric, respectively, and \(\beta _F\) its growth rate. The four parameters \(\left( \uptau /p\right) ^{\mathrm {max}}\), \(\beta _s\) for \(\uptau /p\) and \({F_\mathrm {d}}^{\mathrm {max}}\), \(\beta _F\) for \(F_\mathrm {d}\) are dependent on the volume fraction \(\phi \) and are well described by the general relation from Imole et al. [41] as:

where \(Q_a\), \(Q_c\) and \(\varPsi \) are the fitting constants with values presented in Table 2.

For predictions during cyclic shear deformation, \(\phi _J(H)\) was changed with applied shear strain \({\varepsilon }_{d}\) using Eq. (8). Furthermore, the jamming density is set to a larger value just after strain-reversal, as discussed next.

5.1.3 Behavior of the jamming density at strain reversal

As mentioned in Sect. 3.2, there are some states below \(\phi _J\), where application of shear strain jams the systems. The densest of those can resist shear reversal, but below a certain \(\phi _\mathrm {cr}\approx 0.662<\phi _J\), shear reversal unjams the system again [116]. With this information, we postulate the following:

-

(i)

After the first phase, for large strain pure shear, the system should forget where it was isotropically compressed to before i.e., \({}^M\phi _{J,i}\) is forgotten and \(\phi _J=\phi _{c}\) is realized.

-

(ii)

There exists a volume fraction \(\phi _\mathrm {cr}\), above which the systems can just resist shear reversal and remain always jammed in both forward and reverse shear.

-

(iii)

Below this \(\phi _\mathrm {cr}\), reversal unjams the system. Therefore, more strain is needed to jam the system (when compared to the initial loading), first to forget its state before reversal, and then to re-jam it in opposite (perpendicular) shear direction. Hence, the strain necessary to jam in reversal direction should be higher than for the first shear cycle.

-

(iv)

As we approach \(\phi _{c}\), the reverse strain needed to jam the system increases.

We use these ideas and measure the reversal shear strain \({\varepsilon }_{d}^{SJ,R}\), needed to re-jam the states below \(\phi _\mathrm {cr}\), as shown in Fig. 10. When they are scaled with \(\phi _\mathrm {cr}\) as \(\phi _{sc}= \left( \phi -\phi _{c}\right) /\left( \phi _\mathrm {cr}-\phi _{c}\right) \), they collapse on a unique master curve, very similar to Eq. (7):

shown in the inset of Fig. 6b, with the same power \(\alpha =1.37 \pm 0.01\) as Eq. (7). Fit parameter strain scale \({\varepsilon }_{d}^{0,R}=0.17 \pm 0.002 > {\varepsilon }_{d}^{0} = 0.102\), is consistent with the above postulates (iii) and (iv).

Phase diagram showing the minimum reversal shear strain \({\varepsilon }_{d}^{SJ,R}\) needed to jam the states below \(\phi _\mathrm {cr}\), for states prepared from the first over-compression cycle with different \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\), as given in the legend. The inset shows a collapse of the states using a similar scaled definition as Eq. (7) that includes the distance from both \(\phi _\mathrm {cr}\) and critical jamming density \(\phi _{c}\), using Eq. (15)

The above relations are used to predict the isotropic and the deviatoric quantities, during cyclic shear deformation, as described next, with the additional rule that all the quantities attain value zero for \(\phi \le \phi _J(H)\). Moreover, for any state with \(\phi \le \phi _\mathrm {cr}\), shear strain reversal moves the jamming density to \(\phi _\mathrm {cr}\), and the evolution of the jamming density follows Eq. (15).

Any other deformation mode, can be written as a unique superposition of pure isotropic and pure and axial shear deformation modes [117]. Hence the combination of the above can be easily used to describe any general deformation, e.g. uniaxial cyclic compression (data not presented) where the axial strain can be decomposed in two plane strain modes.

Model prediction for cyclic loading: a Dimensionless pressure \(p\) and b coordination number \(C^{*}\) plotted against volume fraction \(\phi \) for an isotropic compression starting from \(\phi _t= 0.64\) to \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.73\) (small symbols) and decompression (big symbols) back to \(\phi _t\), with \({}^{\infty }\phi _{J,i}=0.667\), for \(M=1\) (red bullet) and for \(M=300\) (blue square). c Deviatoric stress ratio \(\uptau /p\) and deviatoric fabric \(F_\mathrm {d}\), fraction of non-rattlers \(f_\mathrm {NR}\), coordination number \(C^{*}\), pressure p and history dependent jamming density \(\phi _J(H)\) over three pure shear strain cycles (bottom panel) for \(\phi =0.6584\) and initial jamming density \(\phi _J\left( \phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.82, M=1\right) =: {}^1\phi _{J,i}= 0.6652\). Solid lines through the data are the model prediction, involving the history dependent jamming density \(\phi _J(H)\), using Eq. (4) for isotropic deformation and Eq. (8) for shear deformation, and others. Dashed red lines in \(f_\mathrm {NR}\) and \(C^{*}\) represent transition from unjammed to shear jammed states, whereas in \(\phi _J(H)\) the red line indicates the critical jamming density \(\phi _{c}\) (color figure online)

5.2 Prediction: minimal model

Finally, we test the proposed history dependent jamming density \(\phi _J(H)\) model, by predicting \(p\) and \(C^{*}\), when a granular assembly is subjected to cyclic isotropic compression to \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.73\) for \(M=1\) and for \(M=300\) cycles, with \({}^{\infty }\phi _{J,i}=0.667\), as shown in Fig. 11a, b. It is observed that using the history dependence of \(\phi _J(H)\), the hysteretic behavior of the isotropic quantities, \(p\) and \(C^{*}\), is very well predicted, qualitatively similar to isotropic compression and decompression of real 2D frictional granular assemblies, as shown in by Bandi et al. [58] and Reichhardt and Reichhardt [22].

In Fig. 11c, we show the evolution of the deviatoric quantities shear stress ratio \(\uptau /p\) and deviatoric fabric \(F_\mathrm {d}\), when a system with \(\phi =0.6584\), close to \(\phi _{c}\), and initial jamming density \(\phi _J(0)= 0.6652\), is subjected to three shear cycles (lowest panel). The shear stress ratio \(\uptau /p\) is initially undefined, but soon establishes a maximum (not shown) and decays to its saturation level at large strain. After strain reversal, \(\uptau /p\) drops suddenly and attains the same saturation value, for each half-cycle, only with alternating sign. The behavior of the anisotropic fabric \(F_\mathrm {d}\) is similar to that of \(\uptau /p\). During the first loading cycle, the system is unjammed for some strain, and hence \(F_\mathrm {d}\) is zero in the model (observations in simulations can be non-zero, when the data correspond to only few contacts, mostly coming from rattlers). However, the growth/decay rate and the saturation values attained are different from those of \(\uptau /p\), implying a different, independent stress- and structure-evolution with strain—which is at the basis of recently proposed anisotropic constitutive models for quasi-static granular flow under various deformation modes [41]. The simple model with \(\phi _J(H)\), is able to predict quantitatively the behavior the \(\uptau /p\) and \(F_\mathrm {d}\) after the first loading path, and is qualitatively close to the cyclic shear behavior of real 2D frictional granular assemblies, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7 by Bi et al. [7].

At the same time, also the isotropic quantities are very well predicted by the model, using the simple equations from Sect. 5.1, where only the jamming density is varying with shear strain, while all material parameters are kept constant. Some arbitrariness involves the sudden changes of \(\phi _J\) at reversal, as discussed in Sect. 5.1. Therefore, using a history dependent \(\phi _J(H)\) gives hope to understand the hysteretic observations from realistic granular assemblies, and also provides a simple explanation of shear jamming. Modifications of continuum models like anisotropic models [41, 69], or GSH type models [85, 86], by including a variable \(\phi _J\), can this way quantitatively explain various mechanisms around jamming.

6 Towards experimental validation

The purpose of this section is two-fold: First, we propose ways to (indirectly) measure the jamming density, since it is a virtual quantity that is hard to measure directly, just as the “virtual, stress-free reference state” in continuum mechanics which it resembles. Second, this way, we will introduce alternative state-variables, since by no means is the jamming density the only possibility.

a Evolution of the history dependent jamming density \(\phi _J(H)\) during isotropic over-compression to \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i=0.82\) for two cycles, calculated back from the measured quantities: coordination number \(C^{*}\) (green) and pressure p (red), using Eqs. (9) and (11) respectively. The bullet and square represent the first and second cycle respectively. Solid lines are the loading path while the dashed lines the unloading path for the corresponding cycle. Evolution of history dependent jamming density \(\phi _J(H)\) using b coordination number \(C^{*}\) and c pressure p for three levels of over-compression \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i\), as shown in the inset. Solid black line Eq. (4) with \(M=1\), and \({}^{\infty }\phi _{J,i}\) calculated using Eq. (5) (color figure online)

Measuring \(\phi _J\) from experiments Here we show the procedure to extract the history dependent jamming density \(\phi _J(H)\) from measurable quantities, indirectly obtained via Eqs. (9), (10), (11), and directly from Eq. (8). There are two reasons to do so: (i) the jamming density \(\phi _J(H)\) is only accessible in the unloading limit \(p\rightarrow 0\), which requires an experiment or a simulation to “measure” it (however, during this measurement, it might change again); (ii) deducing the jamming density from other quantities that are defined for an instantaneous snapshot/configuration for \(p > 0\) allows to indirectly obtain it—if, as shown next, these indirect “measurements” are compatible/consistent: Showing the equivalence of all the different \(\phi _J(H)\), proofs the consistency and completeness of the model and, even more important, provides a way to obtain \(\phi _J(H)\) indirectly from experimentally accessible quantities.

For isotropic compression Figure 12 shows the evolution of \(\phi _J(H)\), measured from the two experimentally accessible quantities: coordination number \(C^{*}\) and pressure p, using Eqs. (9) and (11) respectively for isotropic over-compression to \(\phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i=0.82\) over two cycles. Following observations can be made: (i) \(\phi _J\) for isotropic loading and unloading can be extracted from \(C^{*}\) and p, (ii) it rapidly increases and then saturates during loading, (iii) it mimics the fractal energy landscape model in Fig. 4 from Luding et al. [114] very well, (iv) while is was assumed not to change for unloading, it even increases, which we attribute to the perturbations and fluctuations (granular temperature) induced during the quasi-static deformations, (v) the indirect \(\phi _J\) are reproducible and follow the same master-curve for first over-compression as seen in Figs. 12, independent of the maximum—all following deformation is dependent on the previous maximum density.

Evolution of the history dependent jamming density \(\phi _J(H)\) during pure shear, calculated back from the measured quantities: coordination number \(C^{*}\), fraction of non-rattlers \(f_\mathrm {NR}\) and pressure p, using Eqs. (9), (10), and (11) respectively, as marked with arrows. The volume fraction is constant, \(\phi =0.66\), and the initial jamming density \(\phi _J\left( \phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.82, M=1\right) =: {}^1\phi _{J,i}= 0.6652\) is greater than \(\phi \) (represented by horizontal cyan line). The solid black line represents Eq. (8), and the dashed vertical line represents the shear strain needed to jam the system, \({\varepsilon }_{d}^{SJ}\), from which on—for larger shear strain—the system is jammed (color figure online)

For shear deformation Figure 13 shows the evolution of \(\phi _J(H)\), measured from the two experimentally accessible quantities: coordination number \(C^{*}\) and pressure p, using Eqs. (9) and (11) respectively during volume conserving shear with \(\phi =0.66\), and the initial jamming density \(\phi _J\left( \phi ^{\mathrm {max}}_i = 0.82, M=1\right) =: {}^1\phi _{J,i}= 0.6652 > \phi \) and shows good agreement with the theoretical predictions using Eq. (8) after shear jamming. Thus the indirect measurements of \(\phi _J(H)\) can be applied if \(\phi _J(H)<\phi \); the result deduced from pressure fits the best, i.e., it interpolates the two others and is smoother.

7 Summary, discussion and outlook

In summary, this study presents a quantitative, predictive macroscopic constitutive model that unifies a variety of phenomena around and above jamming, for quasi-static deformation modes. The most important ingredient is a scalar state-variable that characterizes the packing “efficiency” and responds very slowly to (isotropic, perturbative) deformation. In contrast, it responds fast, saturating exponentially with finite shear deformation. This different response to the two fundamentally different modes of deformation (isotropic or deviatoric, shear) is (qualitatively) explained by a stochastic (meso-scale) model with fractal (multiscale) character. All simulation results considered here are quantitatively matched by the macroscopic model after including both the isotropic and the anisotropic microstructure as state-variables. Discussing the equivalence of alternative state-variables and ways to experimentally measure the model parameters concludes the study and paves the way to apply the model to other, more realistic materials. The following subsections wrap up some major aspects of this study and also add some partly speculative arguments about the wider consequences of our results for rheology as well as an outlook.

7.1 Some questions answered

The questions posed in the introduction can now be answered: (i) The transition between the jammed and flowing (unjammed) regimes is controlled by a single new, isotropic, history dependent state-variable, the jamming density \(\phi _J(H)\) (with history H as shorthand place-holder for any deformation path), which (ii) has a unique lower critical jamming density \(\phi _{c}\) when \(p \rightarrow 0\), reached after long shear without temperature \(T_g\), so that (iii) the history (protocol dependence) of jamming is completely encompassed by this new state-variable, and (iv) jamming, unjamming and shear jamming can all occur in 3D without any friction, only by reorganizations of the micro-structure.

7.2 Lower limit of jamming

The multiscale model framework implies now a minimum \(\phi _{c}\) that represents the (critical) steady state for a given sample in the limit of vanishing confining stress, i.e., the lower limit of all jamming densities. This is nothing but the mean lowest stable random density a sheared system “locally” can reach due to continuously ongoing shear, in the limit of vanishing confining stress.

This lower limit is difficult to access in experiments and simulations, since every shear also perturbs the system leading at the same time to (slow) relaxation and thus a competing increase in \(\phi _J(H)\). However, it can be obtained from the (relaxed) steady state values of pressure, extrapolated to zero, i.e., from the envelope of pressure in Fig. 5. Note that either fluctuations, special deformation modes or careful preparation procedures e.g. energy minimization techniques or manual construction [9, 23] may lead to jammed states at even lower density than \(\phi _{c}\), from which starting to shear would lead to an increase of the jamming density (a mechanism which we could not clearly identify from our frictionless simulations due to very long relaxation times near jamming for soft particles). This suggests future studies in the presence of friction so that one has a wider range of jamming densities and lower density states will be much more stable as compared to the frictionless systems. In this work, we focused on fixed particle size polydispersity with uniform size distribution. We expect the effects of polydispersity [44] will have similar order of explorable jamming range as in this work, whereas friction etc. will cause larger explorable jamming ranges [92] and bigger changes in the calibrated parameters.

7.3 Shear jamming as consequence of a varying \(\phi _J(H)\)

Given an extremely simple model picture, starting from an isotropically unjammed system that was previously compressed or tapped (tempered), shear jamming is not anymore a new effect, but is just due to the shift of the state-variable (jamming density) to lower values during shear. In other words, shear jamming occurs when the state-variable \(\phi _J(H)\) drops below the density \(\phi \) of the system.

Even though dilatancy is that what is typically expected under shear (of a consolidated packing), also compactancy is observed in some cases [41] and can be readily explained by our model. Given a certain preparation protocol, typically a jamming density \(\phi _J> \phi _{c}\) will be established for a sample, since the critical limit \(\phi _{c}\) is very difficult to reach. When next a shear deformation is applied, it depends e.g. on the strain rate whether dilatancy or compaction will be observed: if the shear mode is “slower” than the preparation, or if \(\phi _J> \phi _{c}\), dilatancy is expected as a consequence of the rapidly decreasing \(\phi _J\) of the sample. In contrast, for a relatively “fast”, violent shear test (relative to the previous preparation and possibly relaxation procedure), compactancy also can be the result, due to an increase of \(\phi _J\) during shear.

7.4 Rheology

The multiscale models presented in this study, based on data from frictionless particle simulations, imply that a superposition of the two fundamental deformation modes (isotropic and deviatoric, i.e. plane strain pure shear) is possible or, with other words, that the respective system responses are mostly decoupled as shown for the non-Newtonian rheology of simple fluids in Ref. [117]. Even though this decoupling is mostly consistent with our present data (the responses to isotropic and deviatoric deformations are mostly independent and can be measured independently), this separation and superposition cannot be taken for granted for more realistic granular and powder systems.

Nevertheless, the meso-scale model presented here, as based on a multi-scale energy landscape, explains compactancy and dilatancy, at constant confining stress, as caused by an increasing jamming density, or a decreasing jamming density, respectively (not shown). Similarly, at constant volume, the pressure either decreases or increases (pressure-dilatancy) due to an increasing or decreasing jamming density, respectively.

The model also allows to explain other rheological phenomena as shear-thinning (e.g., due to an increasing jamming density, at constant volume) or shear-thickening (e.g., due to a decreasing jamming density, at constant volume). As generalization of the present work, also the (granular) temperature (fluctuations of kinetic energy) can be considered, setting an additional (relaxation) time-scale, which effects the interplay between (shear) strain-rate and the evolution of the jamming density, so that even in a presumed “quasi-static” regime interesting new phenomena can be observed and explained.

7.5 Towards experimental validation

The history dependent jamming density \(\phi _J(H)\) is difficult to access directly, but can consistently be extracted from other, experimentally measurable quantities, e.g. pressure p, coordination number \(C^{*}\) or fraction of non-rattlers \(f_\mathrm {NR}\). We explain the methodology to extract \(\phi _J(H)\) experimentally, and confirm by indirect measurement, as detailed in Sect. 6, that the jamming density is indeed increasing during isotropic deformation and decreasing during shear, consistently also when deduced from these other quantities.

With other words, we do not claim that the jamming density is the only choice for the new state-variable that is needed. It can be replaced by any other isotropic quantity as, e.g. the isotropic fabric, the fraction of non-rattlers, the coordination number, or an empirical stress-free state that is extrapolated from pressure (which can be measured most easily), as long as this variable characterizes the packing “efficiency”.

Since an increased packing efficiency could be due to ordering (crystallization), we tried to, but could not trace any considerable crystallization and definitely no phase-separation. We attribute this to the polydispersity of the sizes of the particles used being in the range to avoid ordering effects, as studied in detail in Ref. [118]. Quantities like the coordination number, which can tremendously increase due to crystallization, did not display significant deviation from the random packing values and, actually, it even decreases in the unloading phases, relative to the initial loading phase, see Fig. 11b. This is not a proof that there is no crystallization going on, it is just not strong enough to be clearly seen. The reasons and micro-structural origin of the increased packing efficiency, as quantified by the new state-variable, are subject of ongoing research.

7.6 Outlook

Experiments should be performed to calibrate our model for suspended soft spheres (e.g. gels, almost frictionless) and real, frictional materials [119–121]. Over-compression is possible for soft materials, but not expected to lead to considerable relaxation due to the small possible compressive strain for harder materials. However, tapping or small-amplitude shear can take the role of over-compression, also leading to perturbations and increasing \(\phi _J\), in contrast, large-amplitude shear leads to decreasing \(\phi _J\) and can be calibrated indirectly from different isotropic quantities. Note that the accessible range of \(\phi _J- \phi _{c}\) is expected to much increase for more realistic systems, e.g., with friction, for non-spherical particle shapes, or for cohesive powders.

From the theoretical side, a measurement of the multiscale energy landscape, e.g. the valley width, depth/shapes and their probabilities [81] should be done to verify our model-picture, as it remains qualitative so far. Finally, applying our model to glassy dynamics, ageing and re-juvenation, and frequency dependent responses, encompassing also stretched exponential relaxation, see e.g. Lieou and Langer [122], is another open challenge for future research. All this involves the temperature as a source of perturbations that affect the jamming density, and will thus also allow to understand more dynamic granular systems where the granular temperature is finite and not negligible as implied in most of this study for the sake of simplicity. A more complete theory for soft and granular matter, which involves also the (granular) temperature, is in preparation.

Last, but not least, while the macro/continuum model predicts a smooth evolution of the state variables, finite-size systems display (system-size dependent) fluctuations that only can be explained by a meso-scale stochastic model as proposed above, with particular statistics as predicted already by rather simple models in Refs. [28, 123, 124].

Notes

Tapping or compression may not be technically equivalent to the protocol isotropic compression. In soil mechanics, the process of tapping may involve anisotropic compression or shear. The process of compression may be either isotropic or anisotropic or even involving shear. For example, a typical soil tests may include biaxial compression, conventional triaxial compression and true triaxial compression. In this work, in the context of compression, we always mean true isotropic in strain. In the context of tapping, we assume that the granular temperature, which is often assumed isotropic, does the work, even though the tapping process is normally not isotropic. So this is an oversimplification, and subject to future study since it was not detailed here.

This deformation mode represents the only fundamental deviatoric deformation motion (complementary to isotropic deformation), since axial strain can be superposed by two plane-strain modes, and because the plane-strain mode allows to study the non-Newtonian out-of-shear-plane response of the system (pressure dilatancy), whereas the axial mode does not. If superposition is allowed, as it seems to be the case for frictionless particles, studying only these two modes is minimal effort, however, we cannot directly extrapolate to more realistic materials.

For the isotropic deformation tests, we move the (virtual) walls and for the shear tests, we move all the grains according to an affine motion compatible with the (virtual) wall motion. For the case where only the (virtual) walls move some arching near the corners can be seen when there is a huge particle size dispersity or if there is a considerable particle friction (data not shown). For the small polydispersity and the frictionless spheres considered in this work, the system is and remains homogeneous and the macroscopic quantities are indistinguishable between the two methods, however, this must not be taken for granted in the presence of friction or cohesion, where wall motions other than by imposed homogeneous strain, can lead to undesired inhomogeneities in the periodic representative volume element.

The grains are soft and overlap \(\delta \) increases with increasing compression (\(\phi \)). For a linear contact model, it has been shown in Refs. [100, 101] that \(\langle \delta \rangle /\langle r \rangle \propto \mathrm {ln}\left( \phi /\phi _J\right) = -\varepsilon _\mathrm {v}\) (volumetric strain).

References

Denisov, D., Dang, M.T., Struth, B., Wegdam, G., Schall, P.: Resolving structural modifications of colloidal glasses by combining X-ray scattering and rheology. Sci. Rep. 3, 1631 (2013)

Trappe, V., Prasad, V., Cipelletti, L., Segre, P.N., Weitz, D.A.: Jamming phase diagram for attractive particles. Nature 411, 772–775 (2001)

Walker, D.M., Tordesillas, A., Brodu, N., Dijksman, J.A., Behringer, R.P., Froyland, G.: Self-assembly in a near-frictionless granular material: conformational structures and transitions in uniaxial cyclic compression of hydrogel spheres. Soft matter 11, 2157–2173 (2015)

Wambaugh, J., Behringer, R., Matthews, J., Gremaud, P.: Response to perturbations for granular flow in a hopper. Phys. Rev. E 76, 051303 (2007)

Liu, A.J., Nagel, S.R.: Nonlinear dynamics: jamming is not just cool any more. Nature 396, 21–22 (1998)

Song, C., Wang, P., Makse, H.A.: A phase diagram for jammed matter. Nature 453, 629–632 (2008)