Abstract

Humid tropical forests are often characterized by large nitrogen (N) pools, and are known to have large potential N losses. Although rarely measured, tropical forests likely maintain considerable biological N fixation (BNF) to balance N losses. We estimated inputs of N via BNF by free-living microbes for two tropical forests in Puerto Rico, and assessed the response to increased N availability using an on-going N fertilization experiment. Nitrogenase activity was measured across forest strata, including the soil, forest floor, mosses, canopy epiphylls, and lichens using acetylene (C2H2) reduction assays. BNF varied significantly among ecosystem compartments in both forests. Mosses had the highest rates of nitrogenase activity per gram of sample, with 11 ± 6 nmol C2H2 reduced/g dry weight/h (mean ± SE) in a lower elevation forest, and 6 ± 1 nmol C2H2/g/h in an upper elevation forest. We calculated potential N fluxes via BNF to each forest compartment using surveys of standing stocks. Soils and mosses provided the largest potential inputs of N via BNF to these ecosystems. Summing all components, total background BNF inputs were 120 ± 29 μg N/m2/h in the lower elevation forest, and 95 ± 15 μg N/m2/h in the upper elevation forest, with added N significantly suppressing BNF in soils and forest floor. Moisture content was significantly positively correlated with BNF rates for soils and the forest floor. We conclude that BNF is an active biological process across forest strata for these tropical forests, and is likely to be sensitive to increases in N deposition in tropical regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) and nitrogen (N) deposition are the two dominant pathways of N input to most terrestrial ecosystems. Rates of and controls on BNF are not well understood for tropical forests, where mass-balance budgets for N cycles often have outputs that exceed measured inputs. In a review of tropical watershed N budgets, Bruijnzeel (1991) showed large discrepancies between measured N inputs and outputs (from 4 to 16 kg N/ha/y higher outputs), indicating sizeable unmeasured inputs. In two well-studied tropical watersheds in Puerto Rico where the present research was conducted, N outputs and ecosystem accretion of N surpassed measured inputs by 8–19 kg N/ha/y in a lower elevation forest (Chestnut and others 1999), and by 15–17 kg N/ha/y in an upper elevation forest (McDowell and Asbury 1994). The principal unmeasured input of N across these tropical studies was BNF.

In theory, the large ambient pools of soil mineral N common in highly weathered tropical soils (as compared with temperate soils) should inhibit the energetically costly process of BNF (Martinelli and others 1999; Vitousek and Field 1999; Vitousek and Sanford 1986). Despite high mineral N pools in soils, a summary of 12 field studies reported rates of BNF from 15 to 36 kg N/ha/y in tropical forests, with the majority of BNF attributed to symbiotic bacteria in root nodules (Cleveland and others 1999). In addition, non-nodulating (that is, free-living) microbes in litter and soil can contribute sizeable fluxes of N via BNF to tropical ecosystems (Reed and others 2007a; Vitousek and Hobbie 2000). The tropical BNF fluxes are similar to or higher than estimates for temperate forests (7–27 kg N/ha/y) (Cleveland and others 1999). It is possible that high rates of BNF in tropical forests are maintained not for plant N acquisition per se, but rather because production of the soil enzymes that acquire phosphorus (P) or other limiting nutrients require high N inputs (Houlton and others 2008).

Although belowground BNF has received the most attention in forest ecosystem studies, forest canopies can also provide significant inputs of N to humid tropical forests (Leary and others 2004). Canopy BNF has been found in lichens (Benner and others 2007; Forman 1975), mosses (Gentili and others 2005), and leaf epiphylls (Bentley 1987; Goosem and Lamb 1986; Jordan and others 1983) associated with cyanobacteria. The few published rates of aboveground BNF range from less than 1 kg N/ha/y by tropical epiphylls on some tree species (Carpenter 1992; Goosem and Lamb 1986; Reed and others 2008) to 8 kg N/ha/y by lichens on tree branches and boles (Forman 1975). Thus, accounting for BNF in tropical forest canopies may aid in balancing ecosystem N budgets.

Controls on BNF in these different ecosystems compartments may vary, but some basic relationships are likely to hold. At an ecosystem scale, BNF is likely to be sensitive to shifts in C:N ratios and moisture contents of forest substrates. For example, N-fixing decomposers in litter and soil may have a competitive advantage over non-fixers on materials with a high C:N ratio (Mulder 1975; Vitousek and others 2002), because the ratio of C:N required by microbes is much lower than is commonly found in leaf litter (Sylvia and others 1999). Biological N fixation has been positively correlated with the ratio of C to extractable N in litter and soil (Maheswaran and Gunatilleke 1990), positively correlated with soil C content (Vitousek 1994), and negatively correlated with soil N availability (Crews and others 2000). In addition to constraints provided by the relative abundance of nutrients, oxygen is toxic to the nitrogenase enzyme (Sprent and Sprent 1990), and anaerobic conditions can significantly increase rates of BNF (Hofmockel and Schlesinger 2007). Moisture content of soils, forest floor, leaf litter, and wood is linked to oxygen concentration, and can be important in regulating rates of BNF (Hicks and others 2003; Hofmockel and Schlesinger 2007; Wei and Kimmins 1998).

While background BNF is high in some N-rich tropical forests, it is unclear how rates of BNF will respond to increased N availability. Nitrogen deposition in tropical regions is increasing rapidly because of industrialization (Galloway and others 1994; Holland and others 1999; Martinelli and others 2006), such that background N cycles are likely to be altered. Although considerable research has addressed the response of temperate forests to N additions (Aber and others 1995; Aber and Magill 2004; Nadelhoffer and others 1999), less has focused on the effects of increased N on tropical forest ecosystem processes (Matson and others 1999; but see Cleveland and Townsend 2006; Lohse and Matson 2005). As has been observed for other ecosystems, increased N availability may have the potential to inhibit BNF in tropical forests (Compton and others 2004; Marcarelli and Wurtsbaugh 2007). Nitrogen deposition to tropical forests may significantly alter ecosystem stoichiometry (Yang and others 2007), impacting C:N ratios and thus BNF.

Here, we report rates of BNF for above- and belowground components of two distinct tropical forests, and compare rates among five forest compartments with active BNF. We measured rates of N fixation for soil, forest floor, mosses, lichens, and canopy epiphylls. We assessed the effect of increased N availability on BNF in N-rich tropical forests using an on-going N fertilization experiment. We hypothesized that substrate C:N values would be important predictors of BNF within and among forest compartments, reflecting high microbial N requirements relative to substrates with high C:N ratios. We predicted that N fertilization would drive declines in substrate C:N, suppressing BNF. Nodulating legumes are rare or absent in our study sites; thus these data provide some of the first estimates of ecosystem-scale BNF for tropical forests where free-living microbes are the predominant N-fixers.

Methods

Study Site

This study was conducted in the Luquillo Experimental Forest (LEF), an NSF-sponsored Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) site in the Caribbean National Forest, Puerto Rico (Lat. +18.3° N, Long. −65.8° W). Background rates of wet N deposition are still relatively low in Puerto Rico (~3.6 kg N/ha/y), but have more than doubled in the last decade (NADP/NTN 2007). Urban development, landscape transformation, and associated fossil fuel combustion are likely responsible for increasing N deposition in Puerto Rico, where trends are typical of other Caribbean and Latin American areas (Martinelli and others 2006; Ortiz-Zayas and others 2006).

This study was conducted in two distinct forest types at a lower and upper elevation to examine the effects of N additions in diverse tropical conditions. The lower elevation site is a wet tropical rainforest (Bruijnzeel 2001) in the Bisley Experimental Watersheds (Scatena and others 1993) in the Tabonuco forest type (Brown and others 1983). Long-term mean annual rainfall in the Bisley Watersheds is 3537 mm/y (Garcia-Montino and others 1996; Heartsill-Scalley and others 2007), and the plots were located at 260 masl. The upper elevation site is a lower montane rainforest characterized by abundant epiphytes and cloud influence (Bruijnzeel 2001) in the Icacos watershed (McDowell and others 1992) in the Colorado forest type (Brown and others 1983). Mean annual rainfall in the Icacos watershed is 4300 mm/y (McDowell and Asbury 1994), and plots were located at 640 masl. The average daily temperature is 23°C in the lower elevation site, and 21°C in the upper elevation forest (Silver, unpublished data), and average soil temperature decreases from 26°C in the lower elevation forest to 23°C in the upper elevation forest (McGroddy and Silver 2000). The LEF experiences little temporal variability in monthly rainfall and mean daily temperature (McDowell and others 2010).

The two forests differ in tree species composition and structure (Brown and others 1983). Average canopy height is 21 m for the lower elevation forest, and 10 m for the upper forest (Brokaw and Grear 1991). In both forests soils are primarily deep, clay-rich, highly weathered Ultisols with Inceptisols on steep slopes (Beinroth 1982; Huffaker 2002). The soils generally lack an organic horizon (Oa) below the forest floor (Oi). Although the general soil type is similar between the two forests, there are important changes in biogeochemistry with elevation. The upper elevation forest has lower soil redox potential than the lower elevation forest (Silver and others 1999) and poorer drainage. Soil C, N, and P content are higher in the upper elevation forest, and 1 M HCl extractable P increases with elevation in the LEF (McGroddy and Silver 2000).

Nitrogen-fertilization plots in each forest type were established in 2000 at sites described by McDowell and others (1992), and fertilization began in January 2002. Three 20 × 20 m fertilized plots were paired with control plots of the same size in each forest type, for a total of 12 plots. The buffers between plots were at least 10 m, and fertilized plots were located topographically to avoid runoff into control plots. Prior to fertilization, all trees inside plots were identified to species, tagged, and measured for diameter at breast height (dbh, 1.3 m above the ground or buttress) in 2001 (Macy 2004). Starting in 2002, 50 kg N/ha/y was added to the forest floor using a hand-held broadcaster, applied in two annual doses of NH4NO3. Fifty kg N/ha/y is approximately twice the average projected rate for Central America for the year 2050 (Galloway and others 2004), and was selected to be comparable to the low N addition treatment at the Harvard Forest, Massachusetts, where a long-term N deposition experiment is underway (Aber and Magill 2004).

Biological Nitrogen Fixation: Field Experiments

Biological N fixation was measured in the field and in the lab using acetylene reduction assays (ARA) (Hardy and others 1968). Acetylene reduction measures the activity of the nitrogenase enzyme, which reduces N2 to NH3, and also reduces acetylene (C2H2) to ethylene gas (C2H4) in a proportional ratio. We followed the general method in Weaver and Danso (1994), with alterations as noted below. Acetylene gas was generated using CaC2 plus H2O. We report nitrogenase activity as acetylene reduction (AR) in nmol of C2H2 reduced per gram or cm2 of substrate per hour (see below for use of gram versus cm2).

To estimate ecosystem fluxes of N via BNF for each forest compartment, we converted C2H2 reduction to N2 fixation using the ideal ratio for (mol N2 fixed):(mol C2H2 reduced) of 1:3 (Hardy and others 1968). This ratio has been measured empirically using 15N2 gas, and can vary across life forms and ecosystems, with conversion factors as low as 1:23 in nodulating roots (Weaver and Danso 1994), and as high as 50:1 in cyanobacterial crusts in alpine ecosystems (Liengen 1999). However, measurements in tropical ecosystems relatively similar to these Puerto Rican forests have calculated ratios near 1:3 for similar life forms (Crews and others 2001; Vitousek 1994; Vitousek and Hobbie 2000). Using this ideal conversion ratio standardizes fluxes reported here with other studies (DeLuca and others 2002; Reed and others 2008). Thus, rates reported here should be considered potential rates of BNF.

We measured BNF in the primary locations where it has been documented to occur (that is, forest compartments) including soils, forest floor, ground and arboreal mosses and lichens, and canopy leaf epiphylls. Acetylene reduction assays for each sample type were conducted in paired plots (control and fertilized) on the same day to minimize variation in environmental conditions. Samples from each forest compartment were collected into 0.454 l glass vessels with lids fitted with black butyl rubber gas-impermeable Geo-Microbial Technologies septa (for vials ID × OD of 13 × 20 mm; GMT, Ochelata, OK). Ten percent of the headspace was removed with a syringe and replaced with C2H2 gas. Samples were incubated for 2–24 h, until ethylene gas production was detectable. Incubation times were based on rates of C2H2 reduction measured in preliminary assays. For field measurements, glass vessels were incubated in situ on the forest floor within plots of origin. Acetylene was tested for background ethylene content, and ethylene produced naturally by the different sample types was assessed using incubations with ambient headspace gas. In both cases, ethylene was near or below the detection limit. At the end of incubations, headspace gas was sampled from each vessel and stored in an evacuated 20 ml Wheaton glass vial fitted with a black butyl rubber Geo-Microbial Technologies septum. Gas samples plus similarly prepared ethylene reference standards were analyzed on a Shimadzu GC14 gas chromatograph (Shimadzu Corporation, Columbia, Maryland) fitted with a thermal conductivity detector within 4 days of collection at the International Institute of Tropical Forestry laboratory at the USDA Forest Service in Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico, or at the University of California, Berkeley. Samples with nitrogenase activity below our detection limit (C2H4 ppm < 0.05) were remeasured for longer periods, and if still below the detection limit, given a value of zero. For all ARA data presented, recovery of ethylene test standards was greater than 90%, using measured recovery to correct rates for each batch.

Sampling ARA occurred at least 2 weeks after fertilization events, during the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th years of fertilization. Forest floor BNF was measured in the field in July and August of 2004 for both forest types. The forest floor was measured again in August 2005 during a laboratory study. Pilot field measurement of BNF in epiphylls was conducted in August of 2005. Full sampling of soil, canopy epiphyll, moss and lichen BNF were conducted in April and May of 2006 in both forest types. Details of sampling for BNF assays for each sample type are provided below. For ecosystem fluxes, we used measured standing stocks for each forest compartment (see below), and multiplied by average field rates of BNF. We report total N fluxes via BNF to each forest compartment as an hourly rate per m2 of ground area.

Soils and Forest Floor

Soils for ARA were collected from fertilized and control plots of both forest types from 0 to 10 cm depth using a 2.5 cm diameter soil corer. Three to five cores per plot were incubated in the field for 6–10 h; the larger sample size was used in plots with high within-plot variability (that is, standard error >20% of the mean). Soils were then weighed fresh, air-dried, and a subsample was oven dried at 105°C to calculate dry soil mass and soil moisture.

Ten approximately 30 g (dry weight equivalent) samples of bulk forest floor were collected from each plot and incubated in the field for 3 h. For each sample, the full thickness of the forest floor from freshly fallen leaves to the mineral soil surface was sampled, including only recognizable leaf and fine woody (<2 cm diameter) tissue (that is, the Oi horizon). To determine differences in BNF among forest floor components, additional measurements were conducted, separating forest floor leaves from fine woody litter (<2 cm diameter) at paired locations in control plots in the upper elevation forest only (n = 30 paired samples). Field samples were weighed immediately following ARA incubation, then oven dried at 65°C to constant weight to determine dry weight and field moisture content.

To further investigate the importance of moisture for predicting rates of BNF in these forests, we conducted a short laboratory experiment manipulating forest floor moisture. Forest floor was collected from 10 locations in control plots of each forest type and pooled by plot. For each forest type, a “dry” group of pooled litter was air dried in paper bags, a second group of “ambient” litter was kept at field moisture conditions in open plastic containers misted with deionized water, and a “wet” group was kept in open plastic containers and maintained near saturation by misting. After 4 days, five samples from each plot and each moisture level were incubated using ARAs in the laboratory. Moisture content was determined as above, and was significantly different among the three moisture treatments. Moisture content in the “ambient” treatment was not significantly different from average field moisture content (see below). The “dry” treatment represented moisture levels below field averages (0.6 ± 0.1 g water/g dry weight), and the “wet” treatment represented moisture levels above field averages (2.7 ± 0.1 g water/g dry weight).

Soil BNF was scaled up using soil bulk densities measured in each plot using one 0.25 m2 by 0.5 m deep pit, for a total of six bulk density measurements per forest type. Soil for bulk density was collected from undisturbed soil back from the face of each pit, using a 5 cm diameter corer pounded into the soil to 10 cm depth. Soil was then excavated using a palate under the corer to eliminate loss of soil. Each core was weighed for field wet weight, homogenized, and a subsample was oven dried at 105°C to a stable weight to calculate g soil/cm3. Average soil BNF rates from each plot were scaled up using the soil bulk density measured in that plot. Nitrogen fixation in the forest floor was scaled up using measured standing forest floor in each plot. Standing forest floor was collected from five randomly located 15 × 15 cm quadrats in each plot, and oven dried to stable weight at 65°C to determine mass.

Epiphylls, Lichens, and Mosses

BNF was measured for canopy leaf epiphylls and in arboreal and terrestrial mosses and lichens. Because of the high stature of the lower elevation forest, canopy leaves were obtained from a 30-m canopy tower outside the plots. Lower, mid, and upper canopy leaves were collected for ARA from three individual trees of the dominant lower elevation species, Dacryodes excelsa Vahl. Nitrogen fixation was not detected for any canopy leaf samples at the lower elevation site, so further measurements were not taken. Canopy leaves in the upper elevation forest were accessed from the four dominant tree species in the plots with a hand-held pole pruner with extensions for the lower canopy (<6 m) and mid to upper canopy (6–10 m). The dominant tree species in the upper elevation forest is Cyrilla racemiflora L. (CORA), with co-dominance by Clusia krugiana Urban (CLKR), Micropholis chrysophylloides Pierre (MICY), and Micropholis garciniifolia Pierre (MIGA) in the study plots; together these four tree species comprised 87 ± 5% of the basal area across the six upper elevation plots. Six individuals of each of these four tree species were sampled in each plot in April 2006, for a total of 24 individual trees. Pilot measurements of epiphyll BNF were conducted in August 2005 in the lower canopy for 15 individuals, 10 of which were included in the 2006 sampling. For both time points, leaves were removed from clipped branches and incubated in the plots for 6–10 h in glass vessels as above. To standardize leaf wetness, leaves were misted with deionized water prior to incubation. After epiphyll incubations, fresh leaves were refrigerated in plastic bags and total leaf area for each sample was measured using a Li-Cor LI-3100A leaf area scanner (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). Because of the difficulty of collecting epiphyll biomass from leaves, epiphyll BNF is reported on a leaf area (per cm2) basis.

In a preliminary survey in both forest types, the only lichens found to fix N were of crustose morphology, the dominant morphology for lichens in these forests. Crustose lichens were carved off of tree bark for ARA. Because of the destructive nature of the sampling, lichen samples were taken from trees near the outer edges of the plots. Thus, data for lichen activity inside of fertilized plots are not reported. Lichens were grouped by morphology and color, and subsamples were observed under a microscope to confirm the presence of cyanobacteria. Eight individual lichens were sampled in the lower elevation forest, and 15 in the upper elevation forest. Lichens sampled for this study ranged in size from 10 to 115 cm2. Lichens were incubated for 8–24 h. Because of the crustose morphology and the difficulty of separating lichens from bark, lichen BNF is reported by lichen area (per cm2) rather than mass. Area of lichens was measured by tracing each individual onto heavy plastic, and converted using the mass to area ratio of the plastic material.

Mosses were sampled from tree boles up to 8 m heights, on rocks, dead trunks, and downed wood. Leafy liverworts were not distinguished from mosses. Thallose liverworts were tested for nitrogenase activity in a preliminary study, but were not found to fix N in these ecosystems. Moss samples from four to six bryophyte mats were collected per plot and incubated in situ for 3 h. Moisture content and dry weight of each sample were measured as for the forest floor.

Scaling up canopy BNF is more difficult than for soils and forest floor. As an approximation, we scaled epiphyll BNF up using the published leaf area index (LAI) of 4.95 for the upper elevation site (Weaver and Murphy 1990), assuming an average BNF rate generated by the samples from the four dominant species, and estimating lower and upper canopy BNF separately. Because we found no BNF in the dominant tree species in the lower elevation forest we assumed no epiphyll N fixation for this forest. This is likely to underestimate total canopy BNF for this species-rich forest type (approximately 170 total tree species, Brown and others 1983).

Standing stocks of moss and lichen on tree boles and the ground were measured along vertical and horizontal transects to scale up BNF for these forest compartments. Fourteen trees were surveyed in each forest type, eight with DBH equal to 10–25 cm and eight with DBH above 25 cm. Transects were run up tree boles for 2.5–8 m, depending on accessibility. To avoid directional biases of moss and lichen growth on tree boles, transects ran in spirals up boles. Transparent quadrats of 12.5 × 12.5 cm were placed every 0.5 m ascending the tree, with at least five quadrats per tree. Area of lichen coverage was estimated using a transparent grid. Moss within quadrats was destructively sampled and oven dried as above for mass. Bole height (height to first major branching) of each tree was estimated using a hand-held pole. To calculate moss and lichen loads in the lower canopy, boles were estimated to be cylinders up to the first branching, and surface area was calculated using measured DBH. Total stem surface area for each plot was calculated using stem counts and DBH measurements for all trees within plots with DBH above 10 cm. Bole heights for plots were expressed as the average bole height of the sampled trees. This lower region of the canopy where we measured epiphyte loads is equivalent to the base, lower, and upper trunk, or zones I–III according to Johannson (1974). Ground-level moss and lichen loads were measured along four 2 × 20 m transects in each forest type. The area of all lichen and moss on rocks, logs, ground, and stumps was measured, and quadrats of moss were taken for area to mass conversions as above. Because of the destructive nature of this survey, moss and lichen standing stocks were measured near the outside edges of the plots, so we did not scale up BNF rates for the fertilization treatment.

We used our measurements of standing stocks in the lower canopy to estimate the epiphyte loads in the upper canopy (zones IV and V sensu Johannson 1974). To determine a relationship between lower canopy and upper canopy epiphyte loads, we used previous studies in similar ecosystems. Studies in montane rainforests have found moss and lichen occurrence to be highest in the mid canopy above the first tree branching (Holscher and others 2004), or similar in the mid and lower canopies (Kelly and others 2004), with 1–2 times as much epiphyte (Hofstede and others 1993) and bryophyte (Nadkarni 1984) biomass on upper canopy branches versus on the tree bole. In contrast, seasonal rainforest upper canopy moss loads can be as low as 44–60% of loads in the lower canopy, though crustose lichens can be more abundant in the upper versus the lower canopy even for these forest types (Cornelissen and Tersteege 1989). Both forests in this study experience high rainfall with low seasonality (Brown and others 1983). Based on the previous studies listed above and personal observation, we estimated that upper canopy epiphyte loads were equivalent to those measured in the lower canopy for these forests. Epiphyte species composition can vary vertically through the canopy (Gentry and Dodson 1987); however, it is likely that moss and lichens in the mid and upper canopy conduct BNF, as has been found in other tropical forests (Benner and others 2007; Forman 1975). We estimated BNF rates to be similar in the upper and lower canopy for mosses and lichens, whereas the effect of canopy position on nitrogenase activity was measured directly for leaf epiphylls (see above).

Substrate Chemistry

We measured C and N concentrations for soil, forest floor, mosses, and lichens in both forests, and canopy leaves in the upper elevation forest. Air-dried soil samples were ground using a mortar and pestle. For forest floor, moss, and lichen, oven-dried samples were ground in a Wiley mill. Canopy leaves were air-dried and then ground in a Wiley mill. Analysis was conducted on a CE Elantec Elemental analyzer (CE Instruments Lakewood NJ) using acetanalide as a standard for plant tissue, and alanine for soils.

Statistical Analysis

The effects of N fertilization, forest type, and forest compartment on BNF rates were assessed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with field moisture content as a covariate. All interactions were initially included and removed if not significant. We assessed variability in tissue C:N, N concentrations, and standing stocks similarly, including N fertilization, forest type, and forest compartment in an analysis of variance (ANOVA). To explore environmental controls on BNF within each forest compartment, we used multiple regressions with C:N or N concentration, and field moisture as predictors. The effect of moisture and forest type on BNF was assessed using ANCOVA. Differences in BNF between forest floor materials (leaf versus wood) were compared using a paired t test. The effect of tree species, canopy position, and leaf C:N on canopy epiphyll BNF was determined using ANCOVA.

ANOVA and ANCOVA results in the text are followed by model degrees of freedom (DF) and mean square error (MSE), as well as significance levels for individual factors where appropriate. Where ANOVA showed significant effects, we conducted post hoc means comparisons using Fisher’s Least Significant Difference test (LSD, P < 0.05), both for comparison among and within forest compartments, to identify differences among forest types and fertilization treatments. For the forest floor, moisture and BNF rates were compared among the three moisture treatments and field levels using LSD tests. Analyses were performed using JMP software 7.0.2 (SAS Institute). Statistical significance was determined as P < 0.05 for all analyses unless otherwise noted. For all ANOVA, plot-level means for each forest compartment in each forest type were used (n = 3), and averages of untransformed data are reported followed by one standard error (SE). Data were transformed where necessary to meet the assumptions for ANOVA. Because of extreme skewness in the dataset, field BNF data were rank-transformed for analyses unless otherwise noted, whereas moisture, C:N and N concentrations were normally distributed. Gaussian error propagation was used when values were summed, and when multiplying ARA rates by standing stocks (Lo 2005).

Results

Biological Nitrogen Fixation Among Substrates

Acetylene reduction assays showed significant activity of the nitrogenase enzyme in all forest compartments analyzed. Mosses had the highest levels of nitrogenase activity per gram of sample among forest compartments, whereas rates of BNF in soils, epiphylls, and lichens were low (Figure 1). The forest floor had relatively high rates of BNF in both forests. Comparing between the two forest types, BNF in soils and the forest floor were significantly higher in the lower elevation forest (Figure 1). Microscopy revealed that the majority of lichens exhibiting BNF were tripartite (that is, fungus growing with green algae as well as cyanobacteria), with low densities of cyanobacteria. For canopy epiphylls, there were no significant differences in nitrogenase activity between the two time points within species or at the plot level; individual trees maintained relatively stable rates of BNF.

Rates of nitrogenase activity are compared among forest types and fertilization treatments for soil, forest floor, and moss per gram of substrate. Epiphyll and lichen rates are shown per cm2 of leaf and crustose lichen surface area, respectively. Letters indicate significant differences using LSD means separation tests (P < 0.05). Upper case letters indicate significant differences among substrates using all plots (n = 12), lower case letters indicate significant differences within each compartment comparing forest types and fertilization treatments (n = 3). Rates are shown as acetylene reduction (AR) in nmol C2H2 reduced/g substrate dry weight or cm2 substrate/h of incubation. Bars represent average rates ± one SE.

C:N Ratios of Forest Compartments

Among forest compartments, lichens had the highest C:N ratios, whereas soils had the lowest (Table 1). Nitrogen concentrations were highest in mosses and lowest in soils. The four dominant tree species in the upper elevation forest had significantly different foliar C:N and N concentrations: 46 ± 1 and 1.2 ± 0.02% for MICY, respectively; 53 ± 1 and 1.0 ± 0.02% for MIGA; 60 ± 2 and 0.9 ± 0.03% for CORA; 74 ± 3 and 0.7 ± 0.03% for CLKR. Comparing the two forest types, the lower elevation had significantly higher N concentrations and lower C:N ratios than the upper elevation forest for soils, forest floor, and mosses (Table 1).

Nitrogen fertilization had a significant effect on C:N ratios and N concentrations for soils and the forest floor. Including forest type and forest compartment as factors, there was a significant decline in C:N and increase in N concentrations in fertilized plots relative to controls (Table 1; fertilization F-ratio = 5.3, P = 0.02, model DF = 5, MSE = 24 for C:N and 0.04 for % N). The strongest effect of N fertilization on C:N was in the forest floor for both forests, with a significant decline in C:N from 41 ± 5 in control plots to 31 ± 2 in fertilized plots for the lower elevation forest, and from 53 ± 2 in control plots to 46 ± 0.3 in fertilized plots in the upper elevation forest. Soil C:N did not change significantly, but total soil N concentrations increased with fertilization in the upper elevation forest (Table 1). Moss chemistry did not respond to fertilization. There was no overall effect of fertilization on C:N ratios of canopy leaves, but there was a trend toward higher N concentrations in fertilized plots for the lower canopy leaves of MIGA, CLKR, and MICY, and for mid canopy leaves of MIGA in the upper elevation forest (all P = 0.1).

Environmental Controls on Nitrogen Fixation

Average field moisture contents differed more among compartments than between forest types. Moisture contents were 0.85 ± 0.03 for soil, 1.3 ± 0.5 for forest floor, and 4.7 ± 0.4 for moss (g water/g dry sample) in the lower elevation forest; 0.75 ± 0.04 for soil, 1.5 ± 0.2 for forest floor, and 5.0 ± 0.3 for moss in the upper elevation forest (averaging all plots in each forest type, n = 6). In the field, C:N and moisture together explained 29% (P < 0.05) of the variability in soil BNF, with most of this variability explained by moisture (Figure 2A).

Significant log-linear relationships between rates of BNF and A soil field moisture content (filled square), B forest floor laboratory litter moisture content (filled circle), and C canopy leaf C:N (plus). Grey marks lower elevation samples, black marks upper elevation samples. Log fits are shown (all P < 0.05), with the equations: A Ln (BNF nmol N/g/h) = −4.5 + 1.2* (g water/g dry weight) B Ln (BNF nmol N/g/h) = −2.6 + 1.0* (g water/g dry weight) C Ln (BNF nmol N/cm2/h) = −7.7 + 0.03* (C:N).

The laboratory moisture manipulation showed a significant positive effect of moisture on BNF rates in the forest floor, with moisture explaining 21% of the variability across treatments and forest types (Figure 2B). Average BNF rates in the laboratory study were significantly higher for lower elevation forest floor versus the upper elevation (F-ratios = 11 for moisture and 13 for forest type, P < 0.01, model DF = 2, MSE = 1.4), similar to field measurements. For the “ambient” moisture treatment, average forest floor nitrogenase activities measured in the lab in August 2005 were not significantly different from field values measured in June 2004 for either forest type.

Although moisture content correlated positively with BNF in bulk forest floor, higher moisture content of fine woody material versus leaves did not correspond to higher BNF rates in wood. For the upper elevation forest, there were significant differences in BNF between paired samples of leaf and fine woody litter. Both material type and moisture content of leaves and wood were significant predictors of BNF at this scale, with a significant interaction. Nitrogen fixation rates were significantly higher for leaf litter (1.1 ± 0.2 nmol/g/h) than for wood (0.6 ± 0.1 nmol/g/h), although the moisture content of wood was higher than that for leaf litter (1.7 ± 0.1 for wood, versus 1.2 ± 0.1 g water/g dry weight for leaves).

Tree species and foliar C:N were significant factors in the analysis of BNF rates in canopy epiphylls in the upper elevation forest, whereas canopy position was marginally important (F-ratios = 8, 10, 0.2; P = 0.001, 0.05, 0.06, respectively, model DF = 5, MSE = 29). Leaf C:N was a significant predictor of epiphyll BNF, although it only explained 10% of the variation (Figure 2C). The tree species with the highest BNF also had the highest foliar C:N (CLKR, Figure 3), and rates in the mid-canopy were somewhat higher than the lower canopy (Table 1). Neither C:N nor moisture predicted BNF rates in mosses. Using N concentrations instead of C:N did not improve any of these correlations.

Variation in rates of AR by epiphylls growing on leaves of the four dominant tree species in the upper elevation montane forest. Significant differences are shown for species-level averages using a least significant difference (LSD) test. Tree species are Clusia krugiana (CLKR), Cyrilla racemiflora (CORA), Micropholis chrysophylloides (MICY), and Micropholis garciniifolia (MIGA). Means ± one SE are shown (n = 6 individuals per tree species).

Effects of Nitrogen Addition on Nitrogen Fixation

Nitrogen fertilization generally suppressed BNF across forest compartments (Figure 1), with N fertilization and forest compartment the strongest factors in the analysis of BNF rates (F-ratios = 7 and 9, respectively, P < 0.01). Forest type had only a marginal effect on overall BNF (F-ratio = 3, P < 0.1), whereas field moisture content was a strong predictor (F-ratio = 7, P < 0.01). There was a significant interaction between fertilization effect and forest compartment (F-ratio = 3.5, P < 0.05, model DF = 7, MSE = 642.7), with the strongest response of BNF to N fertilization in the forest floor (Table 1). Although fertilization did not affect moss BNF overall, there was a trend toward decreased BNF in fertilized plots for the upper elevation forest (P = 0.1, Figure 1). There was no significant effect of fertilization on epiphyll BNF across species of host tree. Epiphylls on only one tree species, MIGA, had significantly lower BNF in fertilized plots versus control plots (0.005 ± 0.002 vs. 0.02 ± 0.008 nmol C2H2/cm2/h, respectively). This was also the only species with a trend toward increased N concentrations in leaves of both lower and mid canopy (see above).

Ecosystem Rates of Nitrogen Fixation

In both forest types, soils represented the largest standing stock of material, followed by the forest floor (Table 2). There was no significant effect of fertilization or forest type on soil bulk density; standing stocks of forest floor were more variable and were larger in the upper elevation forest relative to the lower elevation forest. There was also a trend toward larger stocks of moss in the upper elevation forest (P = 0.08), with moss loads approximately twice as large as in the lower elevation forest. There was no significant difference in lichen stocks between the two forests.

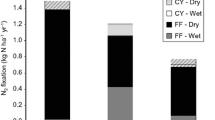

Although BNF rates per gram of soil (0–10 cm depth) were relatively low, soils provided the largest potential fluxes of N to both forest types when scaled up to the ecosystem (Figure 4), because of the large standing stock of soil (Table 2). In the upper elevation forest, total canopy BNF in control plots (moss + epiphyll + lichen BNF = 43 ± 6 μg N/m2/h) was similar to BNF in soils (Table 1). Larger stocks of moss in the upper elevation forest versus the lower elevation forest compensated for relatively lower rates of BNF per gram in the upper elevation, such that total potential fluxes of N via BNF to mosses and lichens were similar for the two forests. Total background BNF fluxes, including all forest compartments, were 120 ± 29 μg N/m2/h in the lower elevation forest, and 95 ± 15 μg N/m2/h in the upper elevation forest. The higher total BNF in the lower elevation forest was primarily because of higher BNF rates in soils.

Background fluxes of N via BNF to each forest compartment are shown for two tropical forest types. Values represent potential rates of BNF per m2 of ground area, and were scaled up using measured soil bulk density (0–10 cm) and forest floor in control plots. Standing stocks of moss were measured outside the plots to scale to the ecosystem, and published LAI (Weaver and Murphy 1990) was used to scale up epiphyll BNF for the upper elevation forest (Table 2). Mean ± one SE (n = 3). Letters indicate significant differences within each forest type using LSD means separation tests (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Patterns in Nitrogen Fixation Across Forest Compartments

The two Puerto Rican forests in this study have rapid rates of N cycling and relatively high N losses (Silver and others 2001, 2005; Templer and others 2008), characteristic of N-rich tropical forests (Martinelli and others 1999). Biological N fixation (BNF) proved to be an active process in all forest strata in these two forests, including in N-rich soils. Despite low activity on a per gram basis relative to other forest compartments, free-living soil microbes provided the largest potential ecosystem inputs of N via BNF. Rates of nitrogenase activity by free-living soil microbes measured in these Puerto Rican soils were near the high end of rates for soils in two Costa Rican rainforests (Reed and others 2007a).

Although soils provided the largest total inputs of N via BNF, mosses had the highest rates of BNF per gram of substrate in both forest types. Biological N fixation in mosses has been identified as an important source of N in boreal forests (DeLuca and others 2002; Lagerstrom and others 2007), but to our knowledge mosses have not previously been identified as providing large fluxes of BNF to tropical forests. In boreal forests, BNF in moss has been estimated to contribute 17–23 μg N/m2/h (DeLuca and others 2002), comparable to rates measured here. In a wet forest on old soils (4.1 × 106 years old) in Hawaii, ground and arboreal bryophytes were estimated to contribute only about 1.4 μg N/m2/h (Matzek and Vitousek 2003). Somewhat higher rates were measured in liverworts (~5 μg N/m2/h) on a 2,000 year-old Hawaiian lava flow (Vitousek 1994). Our results indicate that mosses have the potential to provide large fluxes of N via BNF to some tropical forests on highly weathered soils.

Nitrogen fixation in the forest floor also provided a significant potential flux of N to these forests. Rates of forest floor nitrogenase activity in these two forests were near the low end of values measured in two Costa Rican rainforests (Reed and others 2007a), similar to rates measured on the 2,000 year-old Hawaiian lava flow (Vitousek 1994), and 2–4 times higher than rates in a moist Panamanian forest or on very old Hawaiian soils (4.1 × 106 years) (Barron and others 2009; Crews and others 2000). Nitrogen fixation in the forest floor has been associated with heterotrophic decomposers, which likely fix N because of the higher N requirements of microbial bodies relative to the plant tissues being decomposed (Roper and Ladha 1995; Sylvia and others 1999; Torres and others 2005; Wood 1974). Nitrogen immobilization into decomposing litter is common across tropical forests, and rates of decomposition are sensitive to litter N concentrations in both temperate and tropical forests (Berg and Matzner 1997; Cusack and others 2009; Hobbie and Vitousek 2000; Parton and Silver 2007). In Hawaii, a study over a 2,000-year-old lava flow chronosequence found that BNF increased with soil age, even though N limitation to plant growth diminished along the gradient (Vitousek 1994). The author suggests that this pattern indicates a relative increase in N limitation to C acquisition by decomposers in the forest floor. A similar scenario could explain the substantial BNF in the forest floor of the two Puerto Rican forests studied here. The decline in BNF in both Puerto Rican forests with increased N availability, and the positive correlation of BNF with forest floor C:N in the upper elevation, indicate a link between decomposition and BNF at these sites.

Nitrogenase activity in canopy epiphylls was low relative to other forest compartments in this study, but rates of BNF in the upper elevation forest were similar to rates measured in lowland Costa Rican rainforests (Goosem and Lamb 1986; Reed and others 2008). In Costa Rica, epiphyll BNF was found to increase with light intensity, leaf age, leaf wetness, and mineral nutrient availability, leading to higher BNF in the upper canopy (Bentley 1987), similar to our observations for the lower versus mid/upper canopy. Foliar C:N is an important factor driving epiphyll BNF (Ruinen 1975), and we found that rates differed greatly among the four dominant tree species in the upper elevation forest, corresponding to leaf C:N ratios. Epiphyll BNF has also been shown to vary among tree species in relation to foliar P content (Reed and others 2008), which could be a contributing factor here. Although we did not detect epiphyll BNF in the lower elevation forest, the high stature and diverse plant community composition made it difficult to conduct a thorough survey, so the canopy BNF reported here is likely to be an underestimate. The greater cloud influence and increased rainfall in the upper elevation forest likely correspond to consistently wetter canopy leaves than in the lower elevation, potentially explaining why we only detected epiphyll BNF in the upper forest.

Lichens were not a major source of BNF in these forests, which contrasts with measurements in two other mature tropical moist forests (Benner and others 2007; Forman 1975). At least five lichen genera that associate with N-fixing cyanobacteria have been described for Puerto Rican forests, including Collema, Leptogium, Pannaria, Pseudocyphellaria, and Stricta (Harris 1989), but their densities were very low in the study sites. Lichens can fix substantial quantities (>10 μg N/m2/h) of N on young volcanic soils (Crews and others 2001; Kurina and Vitousek 2001) and in temperate rainforests (Antoine 2004). Although lichen loads can be high in the upper canopies of some montane forests (Cornelissen and Tersteege 1989; Kelly and others 2004), P availability limited epiphyte loads in Hawaii (Benner and Vitousek 2007), and could be one factor contributing to relatively low lichen loads in the Puerto Rican forests.

Patterns in Nitrogen Fixation Between Forest Types

Comparing the two forest types in this study, BNF was lower in the upper elevation forest, with the strongest differences in the forest floor and soil. The decline in temperature from the lower to the upper elevation forest likely contributes to this trend, with the average soil temperature of 26°C in the lower elevation forest (McGroddy and Silver 2000) equal to the global optimum calculated for BNF among forest ecosystems (Houlton and others 2008).

The lignin concentration of litter is another important control on BNF, with low-lignin substrates supporting higher rates of BNF (Vitousek and Hobbie 2000). This relationship could play a role in driving differences between forest floor BNF in the lower and upper elevation forests. We observed lower background rates of forest floor BNF in the upper elevation forest versus the lower elevation, both in the field and in laboratory conditions. Leaf litter from the dominant upper elevation tree species (CYRA) has higher lignin content (22.1%) than litter from the dominant lower elevation species (D. excelsa, 16.6%) (Sullivan and others 1999). Lignin is often negatively correlated with decomposition rates, and its negative effect on free-living microbial BNF in the forest floor may indicate another link between decomposition and N fluxes to tropical forests via BNF.

Controls on Biological Nitrogen Fixation and Effects of Nitrogen Addition

Despite relatively high background soil N availability in these forests (Silver and others 2001, 2005), we found that N fertilization suppressed BNF in soils and the forest floor, similar to findings in a moist forest in Panama (Barron and others 2009). In our study, N was added directly to the forest floor and soil, potentially explaining why these forest compartments responded to fertilization most strongly. In mature tropical forests, atmospheric N deposition is delivered to the canopy first, and tropical forest canopies have shown high retention of deposited nutrients in epiphytic biomass (Clark and others 1998). Canopy leaf chemistry is sensitive to N deposition (Schulze 1989), with potential effects on epiphyll BNF. Although we measured the effects of N addition at the ground level, it seems likely that mosses, epiphylls, and lichens would also have decreased BNF with atmospheric N deposition. Furthermore, the biomass and species composition of arboreal mosses and lichens can change with N deposition, especially if stemflow becomes more acidic (Davies and others 2007; Farmer and others 1991; Rodenkirchen 1992).

Although N fixation in soils and the forest floor were sensitive to N fertilization, rates of BNF among forest compartments did not appear to reflect differences in substrate C:N ratios. On a per gram basis, mosses and the forest floor had the highest nitrogenase activity among forest compartments. Mosses and the forest floor had intermediate C:N ratios relative to soils (low C:N), and canopy leaves and lichens (high C:N). Variation in nitrogenase activity among forest compartments may be more related to differences in assemblages of N fixing microorganisms than to substrate chemistry (Sprent and Sprent 1990). C:N ratios may be more important for driving BNF rates within forest compartments (Maheswaran and Gunatilleke 1990; Mulder 1975; Vitousek and others 2002). Here, substrate C:N was correlated with BNF in the forest floor and in canopy epiphylls, although overall correlations with C:N were weak. Changes in the relative availability of other nutrients important to nitrogenase activity could help explain the lack of strong correlations between C:N ratios and BNF. For example, P provides an important control on BNF in a variety of forest compartments (Benner and others 2007; Reed and others 2007b; Vitousek and Hobbie 2000), as do molybdenum and iron (Barron and others 2009; Howarth and Cole 1985; Howarth and others 1988).

Moisture content was an important predictor of BNF in the forest floor and soils in these two humid tropical forests, and moisture is also an important driver of BNF in temperate forest soils and litter (Hofmockel and Schlesinger 2007; Wei and Kimmins 1998). The importance of moisture content, even though the average moisture content of soils and forest floor was relatively high, may be related to suppressed oxygen levels, promoting higher nitrogenase activity (Hofmockel and Schlesinger 2007). Moisture was not a good predictor of moss BNF, possibly because the moisture content of mosses was consistently greater than 4 g water/g of moss, implying generally saturated conditions. Although moisture was generally a good predictor of BNF in the forest floor, leaf litter had higher BNF rates than fine woody litter, despite the higher moisture content of wood. This discrepancy may be related to the high lignin content of wood. Our results indicate that even in high rainfall tropical forests, small shifts in moisture have the potential to alter ecosystem N inputs via BNF.

Broad-Scale Implications

The difficulty of measuring BNF across forest strata in the tropics has led to few annual estimates of this N input at an ecosystem scale. Although we recognize the limitations of scaling short-term measurements over time, it is valuable as a first approximation to determine potential rates of BNF. The forests in this study have relatively little seasonality in litterfall, temperature, and rainfall (McDowell and others 2010), and previous work at these sites has shown no seasonal patterns in concentration of inorganic N or dissolved organic N (DON) in groundwater (McDowell and others 1992), or soil NH4 + and NO3 − concentrations (Silver and others, unpublished manuscript). If indeed the rates of BNF that we measured are reasonably representative of annual input fluxes, then BNF in these forests would roughly balance previously published N budgets for watersheds at each site (Chestnut and others 1999; McDowell and Asbury 1994). Scaling our summed fluxes up to an annual rate, background BNF is approximately 12.3 ± 2.7 kg N/ha/y in the lower elevation forest, and 8.4 ± 1.4 kg N/ha/y in the upper elevation forest.

The results presented here show that BNF by free-living microbes (that is, non-nodulating) is an active process in N-rich wet tropical forests, with significant variability in potential BNF rates among forest compartments. Arboreal mosses have the potential to provide substantial fluxes of N via aboveground BNF to these forests. Inputs of N via BNF to soils and the forest floor are also likely to be significant in tropical forests on highly weathered soils, even where leguminous trees are absent. Despite high soil N availability and rapid N cycling, BNF in soils and the forest floor showed strong declines with additional N, indicating that N deposition to tropical regions has the potential to alter background N inputs to ecosystems. Furthermore, the sensitivity of BNF to moisture content indicates that potential declines in precipitation with climate change in tropical regions may reduce background fluxes of N to these ecosystems. Thus, global change factors have a great potential to alter BNF activity in wet tropical forests, with declines in this large background flux of N likely.

References

Aber JD, Magill AH. 2004. Chronic nitrogen additions at the Harvard Forest (USA): the first 15 years of a nitrogen saturation experiment. For Ecol Manag 196:1–5.

Aber J, Magill A, McNulty S, Boone R, Nadelhoffer K, Downs M, Hallett R. 1995. Forest biogeochemistry and primary production altered by nitrogen saturation. Water Air Soil Pollut 85:1665–70.

Antoine ME. 2004. An ecophysiological approach to quantifying nitrogen fixation by Lobaria oregana. Bryologist 107:82–7.

Barron AR, Wurzburger N, Bellenger JP, Wright SJ, Kraepiel AML, Hedin LO. 2009. Molybdenum limitation of asymbiotic nitrogen fixation in tropical forest soils. Nat Geosci 2:42–5.

Beinroth FH. 1982. Some highly weathered soils of Puerto Rico.1. Morphology, formation and classification. Geoderma 27:1–73.

Benner JW, Vitousek PM. 2007. Development of a diverse epiphyte community in response to phosphorus fertilization. Ecol Lett 10:628–36.

Benner JW, Conroy S, Lunch CK, Toyoda N, Vitousek PM. 2007. Phosphorus fertilization increases the abundance and nitrogenase activity of the cyanolichen Pseudocyphellaria crocata in Hawaiian montane forests. Biotropica 39:400–5.

Bentley B. 1987. Nitrogen fixation by epiphylls in a tropical rainforest. Ann Mo Bot Gard 74:234–41.

Berg B, Matzner E. 1997. Effect of nitrogen deposition on decomposition of plant litter and soil organic matter in forest systems. Environ Rev 5:1–25.

Brokaw NVL, Grear JS. 1991. Forest structure before and after hurricane Hugo at three elevations in the Luquillo Mountains, Puerto Rico. Biotropica 23:386–92.

Brown S, Lugo AE, Silander S, Liegel L. 1983. Research history and opportunities in the Luquillo Experimental Forest. New Orleans: Institute of Tropical Forestry, USFS.

Bruijnzeel L. 1991. Nutrient input–output budgets of tropical forest ecosystems: a review. J Trop Ecol 7:1–24.

Bruijnzeel LA. 2001. Hydrology of tropical montane cloud forests: a reassessment. Land Use Water Resour Res 1:1–18.

Carpenter EJ. 1992. Nitrogen-fixation in the epiphyllae and root-nodules of trees in the lowland tropical rainforest of Costa-Rica. Acta Oecol Int J Ecol 13:153–60.

Chestnut T, Zarin D, McDowell WH, Keller M. 1999. A nitrogen budget for late-successional hillslope Tabonuco forest, Puerto Rico. Biogeochemistry 46:85–108.

Clark KL, Nadkarni NM, Schaefer D, Gholz HL. 1998. Atmospheric deposition and net retention of ions by the canopy in a tropical montane forest, Monteverde, Costa Rica. J Trop Ecol 14:27–45.

Cleveland CC, Townsend AR. 2006. Nutrient additions to a tropical rain forest drive substantial soil carbon dioxide losses to the atmosphere. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:10316–21.

Cleveland CC, Townsend AR, Schimel DS, Fisher H, Howarth RW, Hedin LO, Perakis SS, Latty EF, Von Fischer JC, Elseroad A, Wasson MF. 1999. Global patterns of terrestrial biological nitrogen fixation in natural ecosystems. Glob Biogeochemical Cycles 13:623–45.

Compton JE, Watrud LS, Porteous LA, DeGrood S. 2004. Response of soil microbial biomass and community composition to chronic nitrogen additions at Harvard Forest. For Ecol Manag 196:143–58.

Cornelissen JHC, Tersteege H. 1989. Distribution and ecology of epiphytic bryophytes and lichens in dry evergreen forest of Guyana. J Trop Ecol 5:131–50.

Crews TE, Farrington H, Vitousek PM. 2000. Changes in asymbiotic, heterotrophic nitrogen fixation on leaf litter of Metrosideros polymorpha with long-term ecosystem development in Hawaii. Ecosystems 3:386–95.

Crews TE, Kurina LM, Vitousek PM. 2001. Organic matter and nitrogen accumulation and nitrogen fixation during early ecosystem development in Hawaii. Biogeochemistry 52:259–79.

Cusack DF, Chou WW, Liu WH, Harmon ME, Silver WL, LIDET-Team. 2009. Controls on long-term root and leaf litter decomposition in Neotropical forests. Glob Change Biol 15:1339–55.

Davies L, Bates JW, Bell JNB, James PW, Purvis OW. 2007. Diversity and sensitivity of epiphytes to oxides of nitrogen in London. Environ Pollut 146:299–310.

DeLuca TH, Zackrisson O, Nilsson MC, Sellstedt A. 2002. Quantifying nitrogen fixation in feather moss carpets of boreal forests. Nature 419:917–20.

Farmer AM, Bates JW, Bell JNB. 1991. Seasonal variations in acidic pollutant inputs and their effects on the chemistry of stemflow, bark and epiphyte tissues in three oak (Quercus petraea ((Mattuschka) Liebl.) woodlands in NW Britain. New Phytologist 118:441–51.

Forman R. 1975. Canopy lichens with blue-green algae: A nitrogen source in a Colombian rain forest. Ecology 56:1176–84.

Galloway JN, Levy H, Kashibhatla PS. 1994. Year 2020—consequences of population-growth and development on deposition of oxidized nitrogen. Ambio 23:120–3.

Galloway JN, Dentener FJ, Capone DG, Boyer EW, Howarth RW, Seitzinger SP, Asner GP, Cleveland CC, Green PA, Holland EA, Karl DM, Michaels AF, Porter JH, Townsend AR, Vorosmarty CJ. 2004. Nitrogen cycles: past, present, and future. Biogeochemistry 70:153–226.

Garcia-Montino AR, Warner GS, Scatena FN, Civco DL. 1996. Rainfall, runoff and elevation relationships in the Luquillo mountains of Puerto Rico. Caribb J Sci 32:413–24.

Gentili F, Nilsson MC, Zackrisson O, DeLuca TH, Sellstedt A. 2005. Physiological and molecular diversity of feather moss associative N2-fixing cyanobacteria. J Exp Bot 56:3121–7.

Gentry AH, Dodson C. 1987. Contribution of nontrees to species richness of a tropical rainforest. Biotropica 19:149–56.

Goosem S, Lamb D. 1986. Measurements of phyllosphere nitrogen fixation in a tropical and two sub-tropical rain forests. J Trop Ecol 2:373–6.

Hardy RWF, Holsten RD, Jackson EK, Burns RC. 1968. The acetylene/ethylene assay for N2 fixation: laboratory and field evaluation. Plant Physiol 43:1185–207.

Harris RC. 1989. Working keys to the lichen-forming fungi of Puerto Rico. Maricao: Catholic University of Puerto Rico.

Heartsill-Scalley T, Scatena FN, Estrada C, McDowell WH, Lugo AE. 2007. Disturbance and long-term patterns of rainfall and throughfall nutrient fluxes in a subtropical wet forest in Puerto Rico. J Hydrol 333:472–85.

Hicks WT, Harmon ME, Griffiths RP. 2003. Abiotic controls on nitrogen fixation and respiration in selected woody debris from the Pacific Northwest, USA. Ecoscience 10:66–73.

Hobbie SE, Vitousek PM. 2000. Nutrient limitation of decomposition in Hawaiian forests. Ecology 81:1867–77.

Hofmockel KS, Schlesinger WH. 2007. Carbon dioxide effects on heterotrophic dinitrogen fixation in a temperate pine forest. Soil Sci Soc Am J 71:140–4.

Hofstede RGM, Wolf JHD, Benzing DH. 1993. Epiphytic biomass and nutrient status of a Colombian upper montane rain forest. Selbyana 14:37–4.

Holland EA, Dentener FJ, Braswell BH, Sulzman JM. 1999. Contemporary and pre-industrial global reactive nitrogen budgets. Biogeochemistry 46:7–43.

Holscher D, Kohler L, van Dijk A, Bruijnzeel LA. 2004. The importance of epiphytes to total rainfall interception by a tropical montane rain forest in Costa Rica. J Hydrol 292:308–22.

Houlton B, Wang Y, Vitousek P, Field C. 2008. A unifying framework for dinitrogen fixation in the terrestrial biosphere. Nature 454:327–31.

Howarth RW, Cole JJ. 1985. Molybdenum availability, nitrogen limitation, and phytoplankton growth in natural waters. Science 229:653–5.

Howarth RW, Marino R, Cole JJ. 1988. Nitrogen-fixation in fresh-water, estuarine, and marine ecosystems. 2. Biogeochemical controls. Limnol Oceanogr 33:688–701.

Huffaker L. 2002. Soil survey of the Caribbean National Forest and Luquillo Experimental Forest, commonwealth of Puerto Rico (interim publication). Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Natural Resource Conservation Service.

Johannson D. 1974. Ecology of vascular epiphytes in West African rain forest. Acta Phytogeogr Suec 59:1–129.

Jordan C, Caskey W, Escalante G, Herrera R, Montagnini F, Todd R, Uhl C. 1983. Nitrogen dynamics during conversion of primary Amazonian rainforest to slash and burn agriculture. Oikos 40:131–9.

Kelly DL, O’Donovan G, Feehan J, Murphy S, Drangeid SO, Marcano-Berti L. 2004. The epiphyte communities of a montane rain forest in the Andes of Venezuela: patterns in the distribution of the flora. J Trop Ecol 20:643–66.

Kurina LM, Vitousek PM. 2001. Nitrogen fixation rates of Stereocaulon vulcani on young Hawaiian lava flows. Biogeochemistry 55:179–94.

Lagerstrom A, Nilsson MC, Zackrisson O, Wardle DA. 2007. Ecosystem input of nitrogen through biological fixation in feather mosses during ecosystem retrogression. Funct Ecol 21:1027–33.

Leary J, Singleton P, Borthakur D. 2004. Canopy nodulation of the endemic tree legume Acacia koa in the mesic forests of Hawaii. Ecology 85:3151–7.

Liengen T. 1999. Conversion factor between acetylene reduction and nitrogen fixation in free-living cyanobacteria from high arctic habitats. Can J Microbiol 45:223–9.

Lo E. 2005. Gaussian error propagation applied to ecological data: post-ice-storm-downed woody biomass. Ecol Monogr 75:451–66.

Lohse KA, Matson P. 2005. Consequences of nitrogen additions for soil losses from wet tropical forests. Ecol Appl 15:1629–48.

Macy J. 2004. Initial effects of nitrogen additions in two rain forest ecosystems of Puerto Rico. Master’s Thesis, Durham: College of Natural Resources, University of New Hampshire.

Maheswaran J, Gunatilleke IAUN. 1990. Nitrogenase activity in soil and litter of a tropical lowland rainforest and an adjacent fernland in Sri Lanka. J Trop Ecol 6:281–9.

Marcarelli AM, Wurtsbaugh WA. 2007. Effects of upstream lakes and nutrient limitation on periphytic biomass and nitrogen fixation in oligotrophic, subalpine streams. Freshw Biol 52:2211–25.

Martinelli LA, Piccolo MC, Townsend AR, Vitousek PM, Cuevas E, McDowell WH, Robertson GP, Santos OC, Treseder K. 1999. Nitrogen stable isotopic composition of leaves and soil: tropical versus temperate forests. Biogeochemistry 46:45–65.

Martinelli LA, Howarth RW, Cuevas E, Filoso S, Austin AT, Donoso L, Huszar V, Keeney D, Lara LL, Llerena C, McIssac G, Medina E, Ortiz-Zayas J, Scavia D, Schindler DW, Soto D, Townsend A. 2006. Sources of reactive nitrogen affecting ecosystems in Latin America and the Caribbean: current trends and future perspectives. Biogeochemistry 79:3–24.

Matson PA, McDowell WH, Townsend AR, Vitousek PM. 1999. The globalization of nitrogen deposition: Ecosystem consequences in tropical environments. Biogeochemistry 46:67–83.

Matzek V, Vitousek P. 2003. Nitrogen fixation in bryophytes, lichens, and decaying wood along a soil-age gradient in Hawaiian montane rain forest. Biotropica 35:12–9.

McDowell WH, Asbury C. 1994. Export of carbon, nitrogen, and major ions from three tropical montane watersheds. Limnol Oceanogr 39:111–25.

McDowell WH, Bowden WB, Asbury CE. 1992. Riparian nitrogen dynamics in two geomorphologically distinct tropical rainforest watersheds—subsurface solute patterns. Biogeochemistry 18:53–75.

McDowell WH, Scatena FN, Waide RB, Lodge DJ, Brokaw NV, Camilo GR, Covich AP, Crowl TA, Gonzalez G, Greathouse EA, Klawinski P, Lugo AE, Pringle CM, Richardson BA, Richardson MJ, Schaefer DA, Silver WL, Thompson J, Vogt D, Vogt K, Willig M, Woolbright L, Zou X, Zimmerman J. 2010. Geographic and ecological setting. Brokaw N, Crowl TA, Lugo AE, McDowell WH, Scatena FN, Waide RB, Willig MW, Eds. Disturbance and response in a tropical forest. New York: Oxford University Press.

McGroddy M, Silver WL. 2000. Variations in belowground carbon storage and soil CO2 flux rates along a wet tropical climate gradient. Biotropica 32:614–24.

Mulder EG. 1975. Physiology and ecology of free-living, nitrogen-fixing bacteria. In: Stewart WD, Ed. Nitrogen fixation by free-living micro-organisms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p 3–29.

Nadelhoffer KJ, Emmett BA, Gundersen P, Kjonaas OJ, Koopmans CJ, Schleppi P, Tietema A, Wright RF. 1999. Nitrogen deposition makes a minor contribution to carbon sequestration in temperate forests. Nature 398:145–8.

Nadkarni NM. 1984. Epiphyte biomass and nutrient capital of a Neotropical elfin forest. Biotropica 16:249–56.

NADP/NTN. 2007. NADP/NTN monitoring location PR20, annual data summaries. National Atmospheric Deposition Program (NADP)/National Trends Network (NTN).

Ortiz-Zayas JR, Cuevas E, Mayol-Bracero OL, Donoso L, Trebs I, Figueroa-Nieves D, McDowell WH. 2006. Urban influences on the nitrogen cycle in Puerto Rico. Biogeochemistry 79:109–33.

Parton W, Silver WL. 2007. Global-scale similarities in nitrogen release patterns during long-term decomposition. Science 315:361–4. Erratum p 940.

Reed SC, Cleveland CC, Townsend AR. 2007a. Controls over leaf litter and soil nitrogen fixation in two lowland tropical rain forests. Biotropica 39:585–92.

Reed SC, Seastedt TR, Mann CM, Suding KN, Townsend AR, Cherwin KL. 2007b. Phosphorus fertilization stimulates nitrogen fixation and increases inorganic nitrogen concentrations in a restored prairie. Appl Soil Ecol 36:238–42.

Reed SC, Cleveland CC, Townsend AR. 2008. Tree species control rates of free-living nitrogen fixation in a tropical rain forest. Ecology 89:2924–34.

Rodenkirchen H. 1992. Effects of acidic precipitation, fertilization and liming on the ground vegetation in coniferous forests of southern Germany. Water Air Soil Pollut 61:279–94.

Roper MM, Ladha JK. 1995. Biological N2 fixation by heterotrophic and phototrophic bacteria in association with straw. Plant Soil 174:211–24.

Ruinen J. 1975. Nitrogen fixation in the phyllosphere. In: Stewart WD, Ed. Nitrogen fixation by free-living micro-organisms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p 85–100.

Scatena FN, Silver W, Siccama T, Johnson A, Sanchez MJ. 1993. Biomass and nutrient content of the Bisley Experimental Watersheds, Luquillo Experimental Forest, Puerto Rico, before and after hurricane Hugo, 1989. Biotropica 25:15–27.

Schulze ED. 1989. Air-pollution and forest decline in a spruce (Picea abies) forest. Science 244:776–83.

Silver WL, Lugo AE, Keller M. 1999. Soil oxygen availability and biogeochemistry along rainfall and topographic gradients in upland wet tropical forest soils. Biogeochemistry 44:301–28.

Silver WL, Herman DJ, Firestone MK. 2001. Dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium in upland tropical forest soils. Ecology 82:2410–16.

Silver WL, Thompson AW, McGroddy ME, Varner RK, Dias JD, Silva H, Crill PM, Keller M. 2005. Fine root dynamics and trace gas fluxes in two lowland tropical forest soils. Glob Change Biol 11:290–306.

Sprent J, Sprent P. 1990. Nitrogen fixing organisms. New York: Chapman and Hall.

Sullivan NH, Bowden WB, McDowell WH. 1999. Short-term disappearance of foliar litter in three species before and after a hurricane. Biotropica 31:382–93.

Sylvia D, Fuhrmann J, Hartel P, Zuberer D, Eds. 1999. Principles and applications of soil microbiology. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Templer PH, Silver WL, Pett-Ridge J, DeAngelis KM, Firestone MK. 2008. Plant and microbial controls on nitrogen retention and loss in a humid tropical forest. Ecology 89:3030–40.

Torres PA, Abril AB, Bucher EH. 2005. Microbial succession in litter decomposition in the semi-arid Chaco woodland. Soil Biol Biochem 37:49–54.

Vitousek PM. 1994. Potential nitrogen-fixation during primary succession in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. Biotropica 26:234–40.

Vitousek PM, Sanford RL. 1986. Nutrient cycling in moist tropical forest. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 17:137–67.

Vitousek PM, Field CB. 1999. Ecosystem constraints to symbiotic nitrogen fixers: a simple model and its implications. Biogeochemistry 46:179–202.

Vitousek PM, Hobbie S. 2000. Heterotrophic nitrogen fixation in decomposing litter: patterns and regulation. Ecology 81:2366–76.

Vitousek PM, Cassman K, Cleveland C, Crews T, Field CB, Grimm NB, Howarth RW, Marino R, Martinelli L, Rastetter EB, Sprent JI. 2002. Towards an ecological understanding of biological nitrogen fixation. Biogeochemistry 57:1–45.

Weaver PL, Murphy PG. 1990. Forest structure and productivity in Puerto Rico Luquillo Mountains. Biotropica 22:69–82.

Weaver R, Danso S. 1994. Dinitrogen fixation. In: Weaver R, Angle S, Bottomley P, Bezdicek D, Smith S, Tabatabai A, Wollum A, Eds. Methods of soil analysis. Part 2: microbiological and biochemical properties, Vol. 5. Madison: Soil Science Society of America, Inc. p 1019–45.

Wei X, Kimmins JP. 1998. Asymbiotic nitrogen fixation in harvested and wildfire-killed lodgepole pine forests in the central interior of British Columbia. For Ecol Manag 109:343–53.

Wood TG. 1974. Field investigations on decomposition of leaves of Eucalyptus delegatensis in relation to environmental factors. Pedobiologia 14:343–71.

Yang XD, Warren M, Zou XM. 2007. Fertilization responses of soil litter fauna and litter quantity, quality, and turnover in low and high elevation forests of Puerto Rico. Appl Soil Ecol 37:63–71.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by an NSF Graduate Student Research Fellowship, an NSF Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant, and a University of California—Berkeley Atmospheric Sciences Center grant to D.F. Cusack. Support was also provided by USDA grant 9900975 to W.H. McDowell, NSF grant DEB 0543558 to W. Silver, and DEB-008538 and DEB-0218039 to the Institute of Tropical Ecosystem Studies, UPR, and USDA-IITF as part of the NSF Long-Term Ecological Research Program in the Luquillo Experimental Forest. Additional support was provided by the Forest Service (U.S. Department of Agriculture) and the University of Puerto Rico. This work was done under the California Agricultural Experiment Station project 7069-MS (W. Silver). We would like to thank D. C. Keck and J. Harte for field assistance, and A. Thompson and D. J. Lodge for laboratory assistance. Helpful insight from A. Townsend and an anonymous reviewer was greatly appreciated.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Cusack, D.F., Silver, W. & McDowell, W.H. Biological Nitrogen Fixation in Two Tropical Forests: Ecosystem-Level Patterns and Effects of Nitrogen Fertilization. Ecosystems 12, 1299–1315 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-009-9290-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-009-9290-0